Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of Contemporary Management

versión On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.10 no.1 Meyerton 2013

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Employee perceptions and entrepreneurial intentions

SM Farrington; G Sharp; V Gongxeka

Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

The perception that a person has of an entrepreneurial career ultimately influences his or her intention of pursuing such a career path. By investigating the perceptions that employees have of starting and managing an own business, the researchers looked for reasons why many individuals remain in the employment of others rather than embarking on an entrepreneurial career for themselves. The primary objective of this study was twofold, to establish the perceptions that employees have of an entrepreneurial career, and to establish the influence of these perceptions on their entrepreneurial intentions. Perceptions of an entrepreneurial career were established in terms of several work values. The data gathered from the 184 usable questionnaires was subjected to various statistical analyses. Multiple regression analysis was undertaken to investigate relationships between the perceptions held of self-employment and entrepreneurial intentions. The work values challenging, future prospects, freedom and time, and autonomy were identified as influencing the entrepreneurial intentions of employees participating in this study.

Key phrases: career perceptions, employee perceptions, entrepreneurial career, entrepreneurial intentions, work values.

1 INTRODUCTION AND PRIMARY OBJECTIVES

Liñán (2008:260) contends that a person's decision to start-up an entrepreneurial venture is influenced by that person's personal preference or attraction towards entrepreneurship. This attraction is influenced by a person's expectations and beliefs about the outcomes, such as personal wealth, autonomy or benefitting the community, resulting from pursuing such behaviour (Almobaireek, Alshmaimeri & Manolova 2011:52). Ashley-Cotleur, King and Solomon (2009:3) propose that a person's attitude and values impact on his or her motivation to be self-employed.

According to Pihie (2009:340), an attitude towards self-employment is a person's perception of working as the owner of a business, and one's attitude towards self-employment is associated with self-employment intentions. Similarly, Sing, Saghafi, Ehrlich and De Noble (2010:394) argue that the decision to become self-employed "is interconnected with how he or she views self-employment". In summary a person's decision to follow a particular career path is influenced by their perception of whether that experience would be desirable or not, if they pursued that particular career.

Blanchflower (2004:25) contends that most individuals have "an unrealistically rosy view of what it is like to be running their own business rather than staying with the comparative security of being an employee". Similarly, Cassar (2010:822) has found "significant over-optimism in the expectations" of emerging entrepreneurs concerning the success of their entrepreneurial activities. The questions thus arise as to how self-employment or entrepreneurship is perceived as a career, and whether these perceptions are related to entrepreneurial intentions.

By investigating the perceptions that employees have of an entrepreneurial career, the researchers looked for reasons why so many people remain in the employment of others rather than embarking on an entrepreneurial career for themselves. The primary objective of this study was twofold, namely to establish the perceptions that employees have of an entrepreneurial career and to establish the influence of these perceptions on their entrepreneurial intentions. By investigating employees' perceptions of business ownership, this study provides insights into how starting and managing an own business is perceived as a career, and also why so few South Africans embark on this career path. Entrepreneurship is regarded by many as the solution to South Africa's social and economic problems. As such, an understanding of the reason why some people become entrepreneurs and others do not could provide solutions on how to stimulate entrepreneurship among all South Africans, and hopefully address some of the economic problems in the country.

For the purpose of this study, employee perceptions of an entrepreneurial career will be investigated in terms of several work values. Work values are important determinants of behaviour, particularly values that influence work attitudes (Twenge, Campbell, Hoffman & Lance 2010:1135). Work values shape employees' perceptions of preference in the workplace, and directly influence their attitudes and perceptions (Twenge et al. 2010:1121). In this study, becoming self-employed or following an "entrepreneurial career" refers to starting and managing one's own small business. Furthermore, the definition of a small business to be applied in this study is a business that is independently owned and managed, and employs fewer than 50 persons. Entrepreneurial intention is a person's intention to engage in entrepreneurship (Drost 2010:28). According to Fatoki (2010:88), entrepreneurial intention is "one's judgement about the likelihood of owning one's own business", whereas Krueger and Carsrud (1993:320) defines entrepreneurial intention as "a commitment to start a new business". As in the case of other studies (Drost 2010:31 ; Kakkonen 2010:71), entrepreneurial intentions in this study refer to the intentions of small business employees to start and manage their own small business, and/or their intentions to follow an entrepreneurial career.

2 DESCRIBING AN ENTREPRENEURIAL CAREER

Work values refer to the outcomes that people desire, and feel that they should achieve through their work; work values influence a person's perceptions of a specific job (Twenge et al. 2010:1121). Judge and Bretz (1991:3) assert that work values are related to the way people feel about their work, to the way they behave in the job context, and to their overall job satisfaction. According to Fatoki and Chindoga (2012:310), work values are important triggers of entrepreneurial intention. For the purpose of this study, the perceptions that employees have of an entrepreneurial career have been established in terms of the work values identified by Farrington, Gray and Sharp (2011:6), namely challenging, stimulating, imaginative, responsibility, stress (reverse), job security, financial benefit, future prospects, flexibility, autonomy, time interaction, prestige and serving the community.

Farrington et al. (2011:5) identified these work values after analysing several studies (e.g. Andersen 2006; Miller 2009; Millward, Houston, Brown & Barrett 2006; What students want 2007) investigating the career perceptions of a variety of different careers. In the present study the aforementioned work values have been categorised as intrinsic, extrinsic, and freedom- and social-related (Cennamo & Gardner 2008: 892). How these work values are experienced in the context of an entrepreneurial career is described in the paragraphs below.

2.1 Intrinsic work values

Intrinsic values relate to satisfaction derived from features of the job and from the job itself. These values occur through the process of work, and include aspects such as creativity, intellectual challenge and stimulation (Cennamo & Gardner 2008:892; Twenge et al. 2010:1121). The work values challenging, stimulating, imaginative, responsibility and stress (reverse) have been categorised as intrinsic work values in this study.

Being an entrepreneur requires one to refine current procedures, identify opportunities, and come up with credible solutions to existing problems (Nieman, Hough & Nieuwenhuizen 2003:15). According to Ward (2004:174), being an entrepreneur is challenging in that one has to consistently generate ideas (be creative) and come up with ways of doing things differently. According to Rwigema and Venter (2004:62), entrepreneurs are required to carry the burden alone, and are responsible for ensuring that business operations run smoothly. Harris, Saltstone and Frabini (1999:447) contend that entrepreneurs are subject to large amounts of stress because of the heavy workload they carry and the role ambiguity they experience. Stress also occurs when entrepreneurs are unable to balance their work and family life (Gholipour, Bod, Zehtabi, Pirannejad & Kozekanan 2010:133). Entrepreneurs regularly feel exhausted, work under constant pressure, and have sleepless nights worrying (Blanchflower 2004:25).

2.2 Extrinsic work values

According to Twenge et al. (2010:1121), extrinsic work values focus on the consequences or outcomes of work, and are unrelated to the job itself. Extrinsic work values are tangible rewards such as financial remuneration, material possessions, job security, and opportunities for advancement (Cennamo & Gardner 2008:892; Duffy & Sedlacek 2007:359; Twenge et al. 2010:1121). The work values job security, financial benefit and future prospects have been categorised as extrinsic in this study.

According to Bosch, Tait and Venter (2011:109), being self-employed comes with the prospect of financial freedom and financial rewards. Entrepreneurs can expect to be compensated for the time and capital that they have invested in the business. However, Benz (2006:12) has found that an entrepreneurial career is not particularly attractive in financial terms. Benz (2006:5) reports that entrepreneurs can expect to start with lower initial earnings than persons in paid employment, and will also experience lower growth of earnings. It is expected that only the most successful entrepreneurs earn similar or higher earnings than employees in paid employment.

2.3 Freedom-related work values

Freedom-related work values concern work-life balance and working hours (Cennamo & Gardner 2008:892; Twenge et al. 2010:1121). For the purpose of the present study, the work values flexibility, autonomy and time have been categorised as freedom-related. An entrepreneurial career provides one with a flexible lifestyle as well as a considerable amount of autonomy and independence (DeMartino & Barbato 2003:816; Petty, Palich, Hoy & Longenecker 2012:12). Having one's own business gives a feeling of being in control of one's own life (Blanchflower 2004:25; Bosch et al. 2011:109) and the prospect of being one's own boss is one of the most highly valued characteristics of entrepreneurship. Benz (2006:10) has found that self-employed people are more satisfied in their jobs because they have more autonomy, greater opportunities to use their skills and abilities, and a higher degree of work flexibility than in an alternative career.

According to Verheul, Carree and Thurik (2009:274), entrepreneurs usually have more flexibility in terms of working hours. However, entrepreneurs can potentially lead very busy lives, being fully occupied with the business (Blanchflower 2004:25). People who work for themselves work very hard, and spend long hours at work (Allen 2012:35; Bosch et al. 2011:110), they give more attention to work than they do to leisure (Blanchflower 2004:25), leaving little time for recreation or activities outside the context of the business (Bosch et al. 2011:111). Similarly, Rwigema and Venter (2004:57) point out that an entrepreneur's family life may suffer as a result of business ownership. Especially in the early years, entrepreneurs have little free time to relax, and friends and family often take a back seat (Bosch et al. 2011:111).

2.4 Social-related work values

Altruistic values relate to issues such as making a contribution to society and helping others through work, whereas status-related values refer to aspects such as prestige, influence and recognition. Social values refer to the need to belong or to be connected through working with people and relationships with others (Cennamo & Gardner 2008:892; Twenge et al. 2010:1121). Given their similarity, the social, status and altruistic work values have been combined into one category for the purpose of this study. This category has been named social-related work values and includes interaction, prestige and serving the community.

Entrepreneurs do not work in isolation; they rely on others for expertise and resources (Allen 2012:35). According to Kuratko and Hodgetts (2007:127), entrepreneurs are required to interact on a regular basis with a diverse range of stakeholders, including regulators, venture capitalists, partners, lawyers, accountants, suppliers, employees and customers.

Bosch et al. (2011:91) contend that individuals who start up entrepreneurial ventures are seen as achievers and are respected in their communities. Furthermore, in South Africa, entrepreneurs are seen as role models and are given heroic status (Bosch et al. 2011:91). Klyver (2010:27) has found that successful entrepreneurs had high levels of respect and status in their communities, and the higher the status and respect, the greater the likelihood of respondents having entrepreneurial intentions. According to Allen (2012:35) and Petty et al. (2012:12), being an entrepreneur gives one the opportunity to make a difference and to make a contribution to one's community.

3 ATTITUDES, PERCEPTIONS AND ENTREPRENEURIAL INTENTIONS

An understanding of the relationship between values, attitude and behaviour is important if one is to understand an individual's work-related behaviour (Ucanok 2009:626). An individual's values are a strong motivational force that influences their behaviour (Ucanok 2009:627). Douglas and Shepherd (1999:232) suggest that when choosing a particular career path, a person must decide whether the desirability of that career option is greater than that of alternative options. The term "desirability" is a form of value (Steel & König 2006:893), and values are considered to be important determinants of behaviour. Perceptions of desirability have been described as "the social and cultural factors that an individual expresses through the process of forming individual values" (Shapero & Sokol 1982). For instance, if one values challenge and excitement, then one is more likely to look for a career that satisfies this need for challenge and excitement (Shapero & Sokol 1982).

According to Twenge et al. (2010:1121), work values shape an employee's preference in the workplace and also influence his/her perceptions, behaviours and judgements regarding a specific job. Therefore, work values play a significant role in influencing and even predicting career choice (Duffy & Sedlacek 2007:359; Judge & Bretz 1991:23). Similarly, Brenner, Pringle and Greenhaus (1991:Internet) maintain that the decision to follow an entrepreneurial career is influenced by the outcomes and values associated with such a career.

In his theory of planned behaviour, Ajzen (1991:188) describes attitude towards the behaviour as the extent to which an individual makes a favourable or unfavourable evaluation of the behaviour in question, and additionally is a function of beliefs applicable to the behaviour. As such, one's attitude towards an entrepreneurial career refers to an individual's perception of working as the owner of a business (Pihie 2009:340), and according to the theory of planned behaviour, one's attitude towards an entrepreneurial career determines one's intentions to embark on such a career path (Urban, Botha & Urban 2010:115). Attitude towards the behaviour has been recognised by several studies as having the strongest influence on entrepreneurial intentions (Gird & Bagraim 2008:717; Gray, Farrington & Sharp 2010:14).

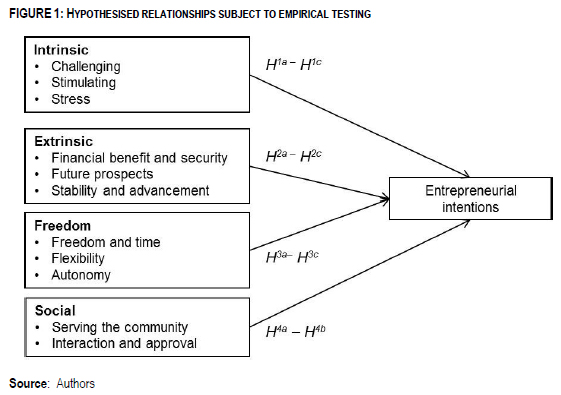

The underlying assumption of the present study is that the more an employee perceives that he or she will experience certain values in the context of an entrepreneurial career, the more likely he or she is to have a favourable attitude towards such a career, which in turn is more likely to lead to such an employee having entrepreneurial intentions. Against this background the following hypotheses are proposed for empirical testing:

H1a, 1c-1e: There is a positive relationship between the perception of the intrinsic-related work values (challenging, stimulating, imaginative and responsibility) as applicable to an entrepreneurial career and the entrepreneurial intentions of employees.

H1b: There is a negative relationship between the perception of the intrinsic-related work value, stress, as applicable to an entrepreneurial career and the entrepreneurial intentions of employees.

H2a-2c: There is a positive relationship between the perception of the extrinsic work values (job security, financial benefit and future prospects) as applicable to an entrepreneurial career and the entrepreneurial intentions of employees.

H3a-3c: There is a positive relationship between the perceptions of the freedom-related work value (flexibility, autonomy and time) as applicable to an entrepreneurial career and the entrepreneurial intentions of employees.

H4a-4c: There is a positive relationship between the perceptions of the social-related work value (interaction, prestige and serving the community) as applicable to an entrepreneurial career and the entrepreneurial intentions of employees.

4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

4.1 Sample and sampling method

Respondents were identified by means of convenience and judgemental sampling, and a survey instrument was administered to 400 employees working in small businesses in the Eastern Cape. The criteria by which respondents were identified and included in the study were as follows: the person had to be in the full-time employment of a small business operating in the Eastern Cape; the small business in which the person was employed had to have been in operation for at least one year, and had to employ fewer than 50 persons. In total, 184 usable questionnaires were returned.

4.2 Data collection and statistical analyses

The 14 work values under investigation were investigated by means of a structured self-administered measuring instrument, consisting of two sections. Section 1 consisted of 77 randomised statements (items) describing what it could be like to run (own and manage) one's own business, as well as several statements relating to entrepreneurial intentions. The items describing what it could be like to run one's own business were sourced from the study of Farrington et al. (2011:15), whereas the items measuring entrepreneurial intentions were sourced from the studies of Fatoki (2010:96), Kakkonen (2010:71) and Gupta, Turbam, Wasti and Sikdar (2009:404). The wordings of these items were retained but contextualised accordingly. Using a 7-point Likert-type scale, respondents were asked to indicate their extent of agreement with regard to each statement. The 7-point Likert-type scale was interpreted as 1 = strongly disagree through to 7 = strongly agree. Section 2 requested information relating to the respondent as well as the small business in which the respondent was employed.

The data collected from 184 usable questionnaires was subjected to various statistical analyses. The software programme Statistica version 10.0 was used for this purpose. Factor analyses were firstly undertaken to assess the validity of the scales measuring the independent and dependent variable. Thereafter, Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the reliability of these scales. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarise the sample data distribution. Lastly, multiple regression analysis was undertaken to establish the relationships between the independent variables (work values) and entrepreneurial intentions.

5 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

5.1 Describing the sample

The majority of respondents participating in the study were female (71.74%) and most were between the ages 21 and 30 years (46.20%). Most respondents were Black (45.11%), followed by White (34.78%) and Coloured/Asian (20.11%). The majority (67.39%) of the respondents indicated that their parents did not own their own business. Most respondents worked in retail (34.80%), services (30.98%) or hospitality/tourism businesses (21.74%). Most (42.39%) of the businesses in which the respondents worked employed between one and four persons. The majority of respondents (86.41%) had been working in these businesses for five years or less. Among the different positions held by the respondents participating in the study, most (44.02%) were general staff members.

5.2 Validity and reliability

A factor analysis of a confirmatory nature was undertaken to assess the validity of the dependent variable entrepreneurial intentions. Confirmatory factor analysis is common when scales from previous research are used to measure certain constructs (Reinard 2006:428), as was the case in this study. In order to assess the validity of the independent variables (work values) an exploratory factor analysis was undertaken. The exploratory factor analysis was undertaken separately on each of the categories of independent variables, namely intrinsic, extrinsic, social- and freedom-related work values. Principal component analysis with a varimax rotation was specified as the extraction and rotation method. In determining the factors to extract, the percentage of variance explained and the individual factor loadings were considered. Items that loaded onto one factor only and reported factor loadings of greater than 0.5 (Mustakallio, Autio & Zahra 2002:212) for both the confirmatory and the exploratory factor analyses were considered significant. Only factors with more than two items measuring that factor were considered for further statistical analysis.

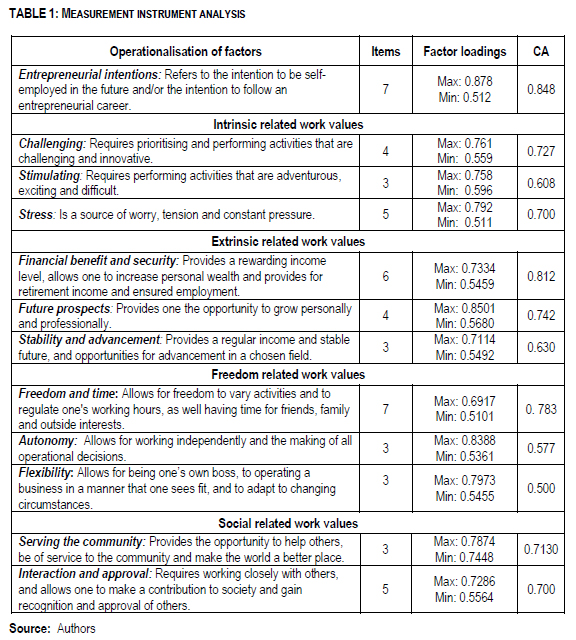

The confirmatory factor analysis revealed that seven of the ten items intended to measure entrepreneurial intentions loaded as expected. However, the exploratory factor analyses revealed that the original items measuring the 14 work values did not load as expected. Several items loaded onto factors that they were originally not intended to measure, and several items did not load onto any factors. The labelling and operationalisation of the affected work values were therefore adapted accordingly (see Table 1).

Cronbach alpha coefficients (CA) were calculated to assess the reliability of the measuring instrument used in this study. According to Nunnally (1978), Cronbach alpha coefficients of greater than 0.70 are considered significant, and deem a scale to be reliable. However, Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham (2006:137) assert that this lower limit may be reduced to 0.60 in certain cases. For the purpose of this study Cronbach alpha coefficients of less than 0.50 are regarded as unacceptable, those between 0.50 and 0.69 are regarded as sufficient, and those above 0.70 as acceptable (Nunnally 1978).

Based on the factor analysis, the operationalisation of several constructs was rephrased (Table 1) and the hypotheses revised (see Figure 1). Given the nature of these revisions, additional theoretical support was not deemed necessary. In addition to the rephrased operational definitions, the number of items, the minimum and maximum factor loadings, and the Cronbach alpha coefficients for each of the constructs are summarised in Table 1.

Factor loadings of > 0.5 were reported for all factors, providing sufficient evidence of validity for the measuring scales. In addition, Cronbach alpha coefficients of greater than 0.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein 1994) were reported for six of the factors, suggesting acceptable reliability for the measuring scales used to measure these constructs. Stimulating, stability and advancement, autonomy and flexibility all reported Cronbach alpha coefficients of less than 0.70 but greater than 0.50, thus indicating sufficient evidence of reliability (Nunnally 1978).

5.3 Descriptive analyses

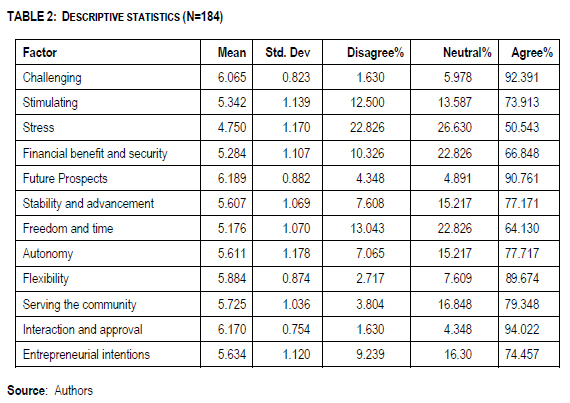

Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarise the sample data distribution (see Table 2). For discussion purposes, response categories on the 7-point Likert type scale were categorised as disagree (1<x<4), neutral (4<x<5) and agree (5<x<8).

The intrinsic work value challenging returned a high mean score of 6.065. The vast majority of respondents (92.40%) agreed that starting and managing an own business requires one to perform activities that are challenging and innovative. Of this majority, only 36.41% 'somewhat agreed' with this description. Stimulating returned a means score of 5.342 with the majority (73.91%) of respondents agreeing that an entrepreneurial career would involve performing activities that are adventurous, exciting and difficult. The independent variable Stress returned the lowest mean score (IMAGEMAQUI = 4.750), with only 50.54% of respondents agreeing that starting and managing their own business would be a source of worry, tension and constant pressure.

The extrinsic work value future prospects reported the highest mean score of 6.189, with the vast majority (90.76%) of respondents agreeing that an entrepreneurial career would give one the opportunity to grow personally and professionally. Stability and advancement returned a mean score of 5.607, while financial benefit and security reported a mean score of 5.248. The majority of respondents (77%) agreed that an entrepreneurial career would provide them with a regular income and a stable future, as well as opportunities for advancement in their field, and 66.85% agreed than starting and managing their own business would provide them with a rewarding income, allowing them to increase personal wealth, provide for retirement income, and ensure employment.

For the freedom-related work values of freedom and time, autonomy and flexibility, mean scores of 5.176, 5.611 and 5.884 were reported respectively. Of the respondents, 64.13% agreed that an entrepreneurial career would allow one the freedom to vary activities, regulate working hours, and have time for friends, family and outside interests, while 77.71% agreed that being an entrepreneur requires one to work independently and make all the operational decisions for business. The majority of the respondents (89.67%) agreed that an entrepreneurial career would allow one to be one's own boss, to operate a business in the manner one sees fit, and to adapt to changing circumstances.

With regard to social-related work values, interaction and approval also reported a high mean score of 6.170, while serving the community reported a mean score of 5.725. The great majority of the respondents (94%) agreed that an entrepreneurial career would require one to be people-orientated, work closely with others and gain their approval. Most of the respondents (79%) also agreed that an entrepreneurial career could give one the opportunity to help others and be of service to the community.

The dependent variable entrepreneurial intentions returned a mean score of 5.634, with the majority of the respondents (74.46%) agreeing that they intended to become self-employed in the future and/or to follow an entrepreneurial career.

5.4 Multiple regression analysis

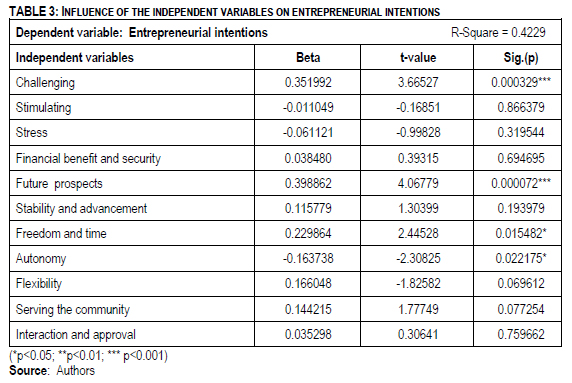

The results of the multiple regression analysis (see Table 3) show that these independent variables explained 42% of the variability in the dependent variable entrepreneurial intentions.

From Table 3 it can be seen that a positive linear relationship (0.3520; p < 0.001) is reported between challenging and entrepreneurial intentions. As this relationship is positive, it suggests that the more an entrepreneurial career is perceived as one where individuals are required to perform activities that are challenging and innovative, the more likely the employees participating in this study would be to pursue such a career. The results also show a positive linear relationship between future prospects (0.3989; p < 0.001) and entrepreneurial intentions. This implies that the more an entrepreneurial career gives one the opportunity to grow personally and professionally, the more likely the employees participating in this study would be to follow such a career.

A significant positive linear relationship is also reported between freedom and time (0.2299; p < 0.05) and entrepreneurial intentions. In other words, it is perceived that the more an entrepreneurial career will allow one freedom to vary activities and to regulate one's working hours, as well as allow one to have time for friends, family and outside interests, the more likely one is to follow such a career. A negative relationship is, however, reported between autonomy (-0.1637; p < 0.05) and entrepreneurial intentions. In other words the more an entrepreneurial career requires one to work independently and make all operational decisions, the less likely one is to follow such a career.

This study found insufficient statistical support for the relationships hypothesised between the independent variables stimulating, stress, financial benefit and security, stability and advancement, flexibility, serving the community, interaction and approval, and the dependent variable entrepreneurial intentions. In other words, whether or not these work values are perceived to exist when following an entrepreneurial career, has no influence on the intentions of the employees participating in this study to follow such a career.

Against this background, support is found for the hypothesised relationships between the work values challenging (H1a), future prospects (H2b) and freedom and time (H3a), and the dependent variable entrepreneurial intentions, but not for the work values stimulating (H1b), stress (H1c), financial benefit and security (H2a), stability and advancement (H2c), flexibility (H3b), autonomy (H3c), serving the community (H4a), and interaction and approval (H4b). Although a significant relationship was reported between autonomy (H3c) and entrepreneurial intentions, the relationship was negative, and the hypothesis was therefore not supported.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The primary objectives of this study were to establish the perceptions that employees had of an entrepreneurial career, and to establish the influence of these perceptions on their entrepreneurial intentions. In order to establish the perceptions that the employees had of an entrepreneurial career (in terms of several work values) descriptive statistics were calculated. Mean scores of between 4.75 and 6.19 (7-point Likert-type scale) were reported for the work values under investigation.

The factors future prospects and interaction and approval returned the highest mean scores, with the majority of respondents agreeing that an entrepreneurial career would give them the opportunity to grow personally and professionally, would require them to work closely with others, and would allow them to make a contribution to society and gain the approval of others. With the exceptions of stress, more than two thirds of the respondents (between 64% and 94%) agreed that all the work values investigated in this study would be realised in the context of an entrepreneurial career. Stress reported the lowest mean score, with only 50% agreeing that starting and managing their own business would be a source of worry, tension and constant pressure.

Given the descriptive statistics reported, it can be concluded that for most of the work values investigated, the perceptions that the employees had of an entrepreneurial career corresponded to the description thereof in the literature. However, the results relating to the perceptions of stress, financial benefits and security and freedom and time, require further discussion. As mentioned above, only 50% of employees agreed that an entrepreneurial career would be stressful. This finding contradicts the literature, where several sources (Blanchflower 2004:25; Gholipour et al. 2010:133; Kuratko & Hodgetts 2007:128) proposed that entrepreneurs are subject to large amounts of stress.

Close to 70% of respondents perceived that an entrepreneurial career provides financial benefits and security. However, Benz (2006:12) reports that an entrepreneurial career is not particularly financially attractive. Furthermore, 65% of respondents agreed that an own business would allow for freedom to vary activities and working hours, and would allow time for friends, family and outside interests. This finding concurs with that of Verheul et al. (2009:274), who assert that entrepreneurs usually have more flexibility and freedom in terms of working hours, but contradicts that of most authors (Bosch et al. 2011:11) who suggest that entrepreneurs work long hours, leaving little time for outside interests, family and friends.

The descriptive statistics suggest that the employees participating in this study had a positive perception of an entrepreneurial career, namely a career that is challenging and stimulating with relatively low levels of stress, a career that provides future prospects, financial benefits and job security, a career that gives one autonomy, flexibility and free time, as well as a career that gives one opportunities for serving the community and interacting with others. It is thus not surprising that almost 75% of respondents agreed that they intended to become self-employed in the future and/or to follow an entrepreneurial career. However, whether these intentions will become a reality or not is unknown. Blanchflower (2004:25) reports that despite a high proportion of respondents in his study showing preference for self-employment, the reality thereof was something different. Although not statistically supported, the findings of this study relating to intentions to become self-employed, as well as the current low levels of entrepreneurial activity reported in South Africa, seem to support Blanchflower's findings (2004).

The following work values were identified as influencing the entrepreneurial intentions of employees participating in this study; challenging, future prospects, freedom and time and autonomy. Future prospects, followed closely by challenging, were found to have the greatest influence on entrepreneurial intentions. The more an entrepreneurial career is perceived to provide the opportunity to grow personally and professionally, and the more an entrepreneurial career requires one to perform activities that are challenging and innovative, the more likely the employees participating in this study would be to pursue such a career.

The results relating to freedom and time and autonomy suggest that the freedom to vary activities and to regulate one's working hours, as well as allow one to have time for friends, family and outside interests, attracted the participants in this study to an entrepreneurial career, whereas the idea of working independently and making all operational decisions (autonomy), did not. Given that working independently and being responsible for making all operational decisions are unavoidable when following an entrepreneurial career, one could suggest that even though employees are positive about entrepreneurship as a career, they would not become entrepreneurs because they do not want the responsibility and independence that goes with it. It is this responsibility and independence, amongst others, that motivates entrepreneurs to become entrepreneurs (Allen 2012:27; Choo & Wong 2006:52). The desire for independence has been found to be a very strong predictor of entrepreneurial intentions (Almobaireek et al. 2011:56). The results and conclusions relating to autonomy should, however, be interpreted in light of the construct's poor reliability.

7 IMPLICATIONS

The findings of this study have implications for both employers and employees. Employees who perceive self-employment as a career that is challenging with low levels of stress, a career that provides future prospects, financial benefits and job security, a career that gives one autonomy, flexibility and free time, as well as a career that gives one opportunities for serving the community and interacting with others, are people who view self-employment in a positive light and could in the future start up their own business. Employers should take note of these individuals as they could become future competitors.

The findings of this study also provide employers with insights into why employees react or behave in certain ways when decisions are made, especially decisions relating to wages and bonuses. Unrealistically high perceptions of the income generated through self-employment are likely to solicit negative reactions when lower than expected wage increases and bonuses are announced. Perceptions of business performance should be managed carefully, and employees should be prepared in advance in terms of whether bonuses or wage increases would be forthcoming or not.

It is important that the employees in a country should have realistic perceptions of what it is like to be self-employed. Employees should be clear about whether they will be able to achieve the work values that are important to them in the context of an entrepreneurial career. Furthermore, they should have a clear and accurate understanding of what having an own business would entail, and what would be expected of them. Unrealistically low perceptions of the responsibility carried and the stress experienced, or unrealistically high perceptions of the income earned and the free-time generated though self-employment could result in individuals not suited to self-employment embarking on such careers. Unrealistic positive perceptions of self-employment could lead to frustration, jealousy and dissatisfaction, whereas unrealistically negative perceptions could discourage people from pursuing such careers. Educators, career counsellors, training institutions and the media have a responsibility to provide a realistic and balanced portrayal of an entrepreneurial career.

8 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The exploratory factor analyses revealed that several items loaded onto factors they were not originally intended to measure, and several items did not load at all. As a result operationalisation was problematic, and reformulation was necessary in the case of certain work values. The entrepreneurial attributes stimulating, stability and advancement, autonomy and flexibility all reported Cronbach alpha coefficients of less than 0.70. Although "sufficient" evidence of reliability was provided for the scales measuring these factors, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Convenience and judgemental sampling was used to identify the potential respondents in this study. Consequently the findings of the study cannot be generalised to the population as a whole. Using scales that rely on one-time individual self-reporting by respondents is a source of potential bias in the study. Investigating whether employees' perceptions of an entrepreneurial career differ from those of their employers could shed light on the behaviour of employees as well as on their attitudes towards their employers. Furthermore, whether demographic factors such socio-economic status, age, gender, and having entrepreneurial parents or not, amongst others, influence the perception of an entrepreneurial career, is a research avenue worth further investigation.

REFERENCES

AJZEN I. 1991. The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decisions Processes, 50:179-211. [ Links ]

ALLEN KR. 2012. New venture creation. 6th edition. Independence, Kentucky: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

ALMOBAIREEK WN, ALSHUMAIMERI AA & MANOLOVA TS. 2011. Entrepreneurial intentions among Saudi university students: The role of motivations and start-up problems. The International Journal of Management and Business, 2(2):51-59. [ Links ]

ANDERSEN EL. 2006. Perception, attitudes and career orientations of recruit police officers. Unpublished MA thesis, Simon Frazer University, Burnaby, Canada. [ Links ]

ASHLEY-COTLEUR C, KING S & SOLOMON G. 2009. Parental and gender influences on entrepreneurial intentions, motivations and attitudes. [Internet: http://www.sbaer.uca.edu/research/usasbe/2003/pdffiles/papers/12.pdf; downloaded on 2012-10-04. [ Links ]]

BENZ M. 2006. Entrepreneurship as a non-profit-seeking activity. Working Paper No. 243, University of Zurich. [Internet: http://www.iew.uzh.ch/wp/iewwp243.pdf; downloaded on 2011-10-18. [ Links ]]

BLANCHFLOWER D. 2004. Self-employment: more may not be better. Working paper 1026. Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Internet: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~blnchflr/papers/finalsweden2.pdf; downloaded on 2011-08-15. [ Links ]]

BOSCH JK, TAIT M & VENTER E. 2011. Business Management: An entrepreneurial perspective. 2nd edition. Port Elizabeth: Lectern. [ Links ]

BRENNER OC, PRINGLE CD & GREENHAUS JH. 1991. Perceived fulfillment of organizational employment versus entrepreneurship: Work values and career intentions of business college graduate. [Internet: http://business.highbeam.com/138001/article-1G1-11403802/perceived-fulfillment-organizational-employment-versus; downloaded on 2011-06-02. [ Links ]]

CASSAR G. 2010. Are individuals entering self-employment overly optimistic? An empirical test of plans and projections on nascent entrepreneur expectations. Strategic Management Journal, 31 (8):822-840. [ Links ]

CENNAMO L & GARDNER D. 2008. Generational differences in work values, outcomes and person-organization values fit. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(8):891-906. [ Links ]

CHOO S & WONG M. 2006. Entrepreneurial intention: triggers and barriers to new venture creations in Singapore. Singapore Management Review, 28(2):47-64. [ Links ]

DEMARTINO R & BARBATO R. 2003. Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: Exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. Journal of Business Venturing, 18:815-832. [ Links ]

DOUGLAS EJ & SHEPHERD DA. 1999. Entrepreneurship as a utility-maximimizing response. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(3):231-251. [ Links ]

DROST EA. 2010. Entrepreneurial intentions of business students in Finland: Implications for education. Advances in Management, 3(7):28-35. [ Links ]

DUFFY RD & SEDLACEK WE. 2007. The Work values of first-year college students: exploring group differences. The Career Development Quarterly, 55:359-364. [ Links ]

FARRINGTON SM, GRAY B & SHARP G. 2011. Perceptions of an entrepreneurial career: Do small business owners and students concur? Management Dynamics, 20(2):2-17. [ Links ]

FATOKI OO & CHINDOGA L. 2012. Triggers and barriers to latent entrepreneurship in high schools in South Africa. Journal of Social Science, 31 (3):307-318. [ Links ]

FATOKI OO. 2010. Graduate entrepreneurial intention in South Africa: Motivations and obstacles. International Journal of Business Management, 5(9):87-98. [ Links ]

GHOLIPOUR A, BOD M, ZEHTABI M, PIRANNEJAD A & KOZEKANAN SF. 2010. The feasibility of job sharing as a mechanism to balance work and life of female entrepreneurs. International Business Research Journal, 3(3):133-140. [ Links ]

GIRD A & BAGRAIM JJ. 2008. The theory of planned behaviour as predictor of entrepreneurial intent amongst final-year university students. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(4):711-724. [ Links ]

GRAY BA, FARRINGTON SM & SHARP GD. 2010. Applying the theory of planned behaviour to entrepreneurial intention. Paper presented at the 4th International Business Conference (IBC), Victoria Falls, Zambia, 12-14 October. [ Links ]

GUPTA VK, TURBAN DB, WASTI A & SIKDAR A. 2009. The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2):397-417. [ Links ]

HAIR JF, BLACK WC, BABIN JB, ANDERSON RE & TATHAM RL. 2006. Multivariate data analysis. 6th edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

HARRIS JA, SALTSTONE R & FRABONI M. 1999. An evaluation of the job stress questionnaire with a sample of entrepreneurs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 13(3):447- 455. [ Links ]

JUDGE TA & BRETZ RD. 1991. The effects of work values on job choice decisions. (CAHRS Working Paper#91-23). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies. [ Links ]

KAKKONEN LM. 2010. International business student's attitude of entrepreneurship. Advances in Business-Related Scientific Research Journal, 1(1):67-77. [ Links ]

KLYVER K. 2010. The cultural embededness of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: a cross-national comparison. [Internet: https://workspace.imperial.ac.uk/.../THORNTON%20-; downloaded on 2011-09-02. [ Links ]]

KRUEGER, NF & CARSRUD AL. 1993. Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 5:315-330. [ Links ]

KURATKO DF & HODGETTS RM. 2007. Entrepreneurship - theory, process, practice. 7th edition. Mason, Ohio: Thomson South Western. [ Links ]

LIÑÁN F. 2008. Skill and value perceptions: how do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship Management Journal, 4:257-272. [ Links ]

MILLER F. 2009. Business school students' career perceptions and choice decisions. Centre for retailing education and research, University of Florida. [Internet: http://warrington.ufl.edu/mkt/retailcenter/docs/CRER_AStudyOfCareerChoiceDecisions.pdf; downloaded on 2009-05-20. [ Links ]]

MILLWARD L, HOUSTON D, BROWN D & BARRETT M. 2006. Young people's job perceptions and preferences. Final Report to the Department of Trade and Industry. Guildford: University of Surrey. [ Links ]

MUSTAKALLIO M, AUTIO E & ZAHRA A. 2002. Relational and contractual governance in family firms: Effects on strategic decision making. Family Business Review, 15(3):205-222. [ Links ]

NIEMAN G, HOUGH J & NIEUWENHUIZEN C. 2003. Entrepreneurship: a South African perspective. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

NUNNALLY JC & BERNSTEIN IH. 1994. Psychometric theory. 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

NUNNALLY JC. 1978. Psychometric theory. 2nd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PETTY JW, PALICH LE, HOY F & LONGENECKER JG. 2012. Managing small business. 16th edition. Independence, Kentucky: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

PIHIE ZAL. 2009. Entrepreneurship as a career choice: an analysis of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention of university students. European Journal of Social Sciences. 9(2):338-349. [ Links ]

REINARD JC. 2006. Communication research statistics. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE. [ Links ]

RWIGEMA H & VENTER R. 2004. Advanced entrepreneurship. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

SHAPERO A & SOKOL L. 1982. The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. Encyclopaedia of Entrepreneurship, 4(2):72-90. [ Links ]

SING G, SAGHAFI M, EHRLICH S & DE NOBLE A. 2010. Perceptions of self-employment among mid-career executives in the People's Republic of China. Journal of Career Assessment, 18(4):393-408. [ Links ]

STEEL P & KÖNIG CJ. 2006. Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review, 31 (4):889-913. [ Links ]

TWENGE JM, CAMPBELL SM, HOFFMAN BJ & LANCE CE. 2010. Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. Journal of Management, 36(5):1117-1142, September. [ Links ]

UCANOK B. 2009. The effects of work values, work value congruence and work centrality on organisational citizenship behaviour. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences, 4(9):626-639. [ Links ]

URBAN B, BOTHA JBH & URBAN COB. 2010. The entrepreneurial mindset. Kempton Park: Heinemann. [ Links ]

VERHEUL I, CARREE M & THURIK R. 2009. Allocation and productivity of time in new ventures of female and male entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 33:273-291. [ Links ]

WARD TB. 2004. Cognition, creativity and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 19:173-188. [ Links ]

WHAT STUDENTS WANT: CAREER DRIVERS, EXPECTATIONS AND PERCEPTIONS OF MINERAL ENGINEERING AND MINERALS PROCESSING STUDENTS. 2007. Minerals Council of Australia. Centre for responsibility in mining. University of Queensland, Australia. [Internet: http://www.minerals.org.au/data/assets/pdf_file/0004/19813/MCA_CSRM_What_Students_Want300407.pdf; downloaded on 2009-05-21. [ Links ]]