Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.9 no.1 Meyerton 2012

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Linking corporate entrepreneurship and culture to firm performance in the South African ICT sector

B Urban; J Barreria; B T Nkosi

Wits Business School, University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

The ICT sector in South Africa is pivotal to economic development, and innovation as a corporate strategy is a logical response to the presence of industry related environmental conditions, in terms of competitive intensity, technological change and evolving product-market domains. Despite the importance of this sector, little in-depth research regarding corporate entrepreneurship has been undertaken in the ICT industry context. This study contributes to existing literature and extends current knowledge of corporate entrepreneurship by linking it with culture and firm performance. Based on a web-survey, 114 firms in the ICT sector were studied in terms of any evidence of an entrepreneurial orientation and culture, as well as organisational performance which was measured with various growth indicators. The empirical findings emanating from this study show that the entrepreneurship orientation and culture have a significant and positive relationship with higher company performance, adding support to all of the study hypotheses. The study provides guidance to managers and company leaders interested in undertaking intrapreneurial practices and accessing links to firm performance.

Key phrases: corporate entrepreneurship, ICT sector, innovation, firm performance,

1 INTRODUCTION

Corporate Entrepreneurship (CE) is widely recognised as a viable means for promoting and sustaining corporate competitiveness and performance (Covin & Miles 1999; Groenewald & Van Vuuren 2011 ; Morris, Kuratko & Covin 2008; Vozikis, Bruton, Prasad & Merikas 1999). The presence of CE leads to positive outcomes (Ireland, Covin & Kuratko 2009:21), where top management needs to adopt an entrepreneurial strategy and be able to cascade this through different levels within the company. Entrepreneurial behaviour by management and employees has been linked to a firm's competitive advantage and sustainability (Dess, Lumpkin & McGee 1999:86; Landstrom, Crijns, Lavern & Smallbone 2008; Zahra & Covin 1995).

Entrepreneurship within organisations is a fundamental posture, instrumentally important to strategic innovation, particularly under shifting external environmental conditions (Knight 1997:214; Urban 2010a:56). Adopting an entrepreneurial strategic vision is a logical response to the presence of industry related environmental conditions, in terms of competitive intensity, technological change and evolving product-market domains (Anderson, Covin & Slevin 2009:220; Ireland, Covin & Kuratko 2009:23). The information and communication technology (ICT) industry is one such environment characterised by rapid change and shortened product and business lifecycle, where the future profit streams from existing operations are uncertain and firms need constantly to seek out new opportunities (Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin & Frese 2009:763; Wang 2008:637).

Technology-based firms can play a number of important roles in any industry and economy. Such firms can facilitate change within an industry by introducing both product and process innovations which force larger, more-established firms to rethink their technologies and operations. Additionally, technology enterprises can provide societal value by helping to expand the tax base, strengthen national competitiveness and generate highly skilled jobs (Preece, Miles & Baetz 1998:261).

The important role that technology enterprises can play in the development of emerging economies is being increasingly recognised (Preece et al. 1998:259; Wright, Hmieleski, Siegel & Ensley 2007:794). The ICT sector in South Africa is facing rapid technological changes, where firms are required to remain innovative to maintain their competitive advantage and sustainability (Covin & Miles 1999; Moreno & Casillas 2008; Wakkee, Elfring & Monaghan 2010; Wiklund 2009).

The ICT sector in South Africa, is pivotal to economic development, and innovation as a turnkey strategy of globalisation, particularly in telecommunications, in terms of identified national policy objectives which include promoting the convergence of telecommunications, broadcasting and information technologies; the development of interoperable and interconnected electronic networks; technologically neutral licensing; universal access and connectivity for all; investment and innovation in communications; efficient use of radio spectrum; and the promotion of competition (Esselaar, Gillwald, Moyo & Naidoo 2010:7; Hoffmann & Marcus 2011:95).

2 PURPOSE OF STUDY AND AIMS

Despite the importance of this sector, little in-depth research regarding CE has been undertaken in the ICT industry context, with an absence of empirical studies testing the relationship between CE activities and firm performance. Consequently it has been argued that if CE is to be employed by ICT companies as a strategy for survival, it is critical that this link be empirically investigated in the context of this industry. This problem is reinforced when Gries and Naude (2010:29) suggest that firms need to develop new and improved products and services, as well as better operating technology and methods that are more effective than those of competitors to ensure a competitive advantage. Indeed many firms are seeking to transform their organisations and particularly to use entrepreneurial orientation (EO) as a way of combating the lethargy and bureaucracy that often accompany business size and cultural lock-ins (Burns 2004:21).

It is imperative to note that in every organisation, there is an element of EO and within the most bureaucratic organisations there exists some element of highly entrepreneurial people (Morris et al. 2008:366; Van Vuuren, Groenewald & Gantsho 2009:327). Additionally, entrepreneurially oriented companies tend to establish clear and meaningful core values and ensure they are shared within the organisation (Morris et al. 2008:56). Entrepreneurial organisations are guided by their vision, and exhibit a sustained form of CE through cultures and systems supportive of innovation (Covin & Miles 1999:49). An entrepreneurial culture stimulates innovation, flexibility and performance (Lumpkin & Dess 1996:137), and should be encouraged throughout the organisation by fostering an entrepreneurial climate (Venter, Urban & Rwigema 2008:506).

The research question this study seeks to address is whether or not there are any significant relationships or links between the various dimensions of EO, entrepreneurial culture and financial measures of firm performance in the South African ICT sector. Building on existing theoretical and conceptual frameworks, this study has relevance to academics, senior decision makers, and practitioners. The study contributes to existing literature and extends current knowledge of the EO construct by linking it with culture and applying it to an under-researched context, the ICT sector in an emerging market context (Perks, Muteti, Pietersen & Bosch 2010:541). The study aids in understanding the nexus between the various dimensions of EO and performance, thereby advancing the knowledge of entrepreneurial practices in this highly dynamic and competitive industry.

A deep and thorough understanding of the nexus between entrepreneurship at the firm level and firm performance is important not only for academic purposes but also has salience for practitioners and policy makers. These implications relate to firm profitability and competitiveness as well as to the overall economic performance of the ICT industry and the national economy.

The study starts by briefly reviewing past research on CE, EO, culture and performance in order to operationalise the constructs under investigation. The research methodology is then delineated, in terms of sampling, instrument design, and data analysis best suited to test the hypotheses. The results are scrutinized in terms of previous theory and interpreted from an industry specific perspective. Both theoretical and practical implications are drawn from the empirical evidence, and recommendations for future research are made.

3 LITERATURE REVIEW

3.1 Corporate Entrepreneurship

A longstanding literature has conceptualised CE as a multidimensional phenomenon which incorporates the behaviour and interactions of the individual, organisational, and environmental elements within organisations (Antoncic & Hisrich 2001; Dess et al. 1999; Hayton, George & Zahra 2002; Phan, Wright, Ucbasaran & Tan 2009). CE includes strategic renewal (organisational renewal involving major strategic and/or structural changes), innovation (the introduction of something new to the marketplace), and corporate venturing (corporate entrepreneurial efforts that lead to the creation of new companies within the corporate company), all of which have identified as important and legitimate parts of the CE process (Covin & Miles 1999:52; Kuratko, Ireland & Hornsby 2001:61 ; Morris & Kuratko 2002:34).

By adopting CE practices companies are able to maintain and increase their sustainable competitive capabilities, which are fostered by different areas of organisational performance (Agca, Topal & Kaya 2009:3; Lumpkin & Dess 1996, 2001; Ireland et al. 2009).

3.2 Entrepreneurial Orientation

For CE to become a meaningful strategy it cannot be confined to a specialist function within the organisation, but rather requires support through an entire pro-entrepreneurship organisational architecture that contains key attributes that individually and collectively encourage entrepreneurial behaviour. This type of entrepreneurial behaviour is manifested through a firm's entrepreneurial orientation (EO). EO incorporates firm-level processes, practices and decision-making styles (Lumpkin & Dess 1996:136) where entrepreneurial behavioural patterns are recurring (Covin & Slevin 1991:8; Dess et al. 2003:361).

Firms with higher levels of EO would reflect consistent behaviour required to enact a CE strategy as captured in the CE strategy model through entrepreneurial processes and behaviour, including its EO (Ireland et al. 2009:26; Pienaar & Du Toit 2009:123). EO is one of the prerequisites for organisational success, where Antoncic and Hisrich (2004:519), point out that any organisation with high levels of EO tends to be innovative and encourages creative initiatives in new products and service development, particularly in the space of advancement of new technologies and novel ideas.

3.3 Organisational Performance

Organisational performance in a fast and changing environment requires an entrepreneurial approach, where Huse, Neubaum and Gabrielsson (2005:315) maintain that emerging global markets and rapid technological developments make strong demands on the ability of companies to develop and utilise their resources in order to meet their customer demands. These firms are flexible to environmental dynamics, which allows them to identify new opportunities caused by disequilibrium (Huse et al. 2005:316). Several studies have empirically tested the influence of CE and EO on company performance and sustainability (Sebora & Theerapatvong 2009:5; Ireland et al. 2009:25; Zahra & Covin 1995:45; Lumpkin & Dess 1996:138).

For instance Wiklund (1999:39) finds that the impact of CE on company performance has a positive effect. In Wiklund study's the results indicate a strong relationship over time, which means that CE is effective within the organisation over a certain period. Similarly Zahra and Garvis (1998:469) report that CE is positively associated with company performance, where the EO dimension of innovation has a more positive relationship with company performance, especially if it is an international company. Moreover, CE has also been identified as an important predictor of company growth in the South African context (Urban 2010b:3, Urban & Oosthuizen 2009:174). Higher growth tends to be associated with firms that support entrepreneurial behaviour and display an entrepreneurial culture (Moreno & Casillas 2008:509).

3.4 Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organisational Performance

The EO construct is salient not only for large organisations but also for small and medium-sized organisations, under different stages of economic development, in varied cultural contexts (Lumpkin & Dess 1996, 2001). The theoretical basis of the EO construct lies in the assumption that all firms have an EO, even if levels of EO are very low. Extensive research confirms that EO has three dimensions: innovativeness, risk taking, and proactiveness (Covin & Slevin 1989, 1991, 1997; Kreiser, Marino & Weaver 2002). These dimensions have been extensively documented, and according to Lumpkin and Dess (1996:156), all the dimensions are central to understanding the entrepreneurial process, although they may occur in different combinations, depending on type of entrepreneurial opportunity the firm pursues.

The different EO dimensions and the construct of entrepreneurial culture are briefly delineated in terms of their potential influence on firm performance. Innovativeness is the fundamental posture of an entrepreneurial organisation in terms of developing new products or inventing new processes (Drucker 1979; Schumpeter 1934). According to Huse et al. (2005), and Venter et al. (2008:514), firms operating in turbulent environments are often characterised by rapid and frequent new product creation and high levels of research and development. Risk taking involves taking bold actions by venturing into the unknown, borrowing heavily and/or committing significant resources to ventures in uncertain environments (Wang 2008; Lumpkin, Cogliser & Schneider 2009; Rauch et al. 2009; Zahra and Garvis 1998:471). Risk-taking, according to Yi and Lau (2008:38), is a commitment to experimentation in the face of uncertainty. Subsequently these activities can enhance the company's ability to recognise and exploit market opportunities ahead of its competitors and improve performance (Hitt, Ireland, Camp & Sexton 2002; Kreizer & Davis 2010:41). Proactiveness is perseverance in ensuring initiatives is implemented, and is concerned with adaptability and tolerance of failure (Lumpkin & Dess 1996). According to Zahra, Nielsen and Bogner (1999), pro-activeness such as first entry, can improve a firm's performance.

Wang (2008) reports that culture is an important controlling instrument for CE practices, because it provides a space for taking risks and a certain degree of immunity from failure. An entrepreneurial culture at a firm empowers its people and gives them freedom to decide and act by devolving decision-making authority (Morris et al. 2008). Entrepreneurship may be encouraged in an organisation by creating an appropriate entrepreneurial culture and fostering an entrepreneurial climate (Venter et al. 2008). Entrepreneurship culture encourages learning through information sharing, commitment and accountability (Morris et al. 2008). As innovation is a key element of EO, it can be influenced by cultural factors of different countries (Huse et al. 2005). Zahra et al (1999) indicate that the culture that reinforces communication and sharing of knowledge within the organisation is a crucial element of success in encouraging the implementing of new ideas. Entrepreneurial firms are more prone to having a market-driven culture by constantly updating, improving and changing business processes, products and services that eventually create more value for customers (Agca et al. 2009).

Firms can only be labelled as entrepreneurial if they are simultaneously risk taking, innovative, and proactive, and have an entrepreneurial culture (Covin & Slevin 2002; Urban & Oosthuizen 2009). Consequently an overall first hypothesis is formulated to reflect the consolidated nature of EO on firm performance. Four separate hypotheses are further formulated to discern if any associations between the EO dimensions, entrepreneurial culture and form performance is evident. The formulation of these hypotheses allows for the testing of both one-dimensional and the multidimensional levels of the EO construct.

Hypothesis 1: Higher levels of EO and culture are positively associated with higher levels of firm performance in the South African ICT sector

Hypothesis 2: The EO dimension of innovation is positively related with higher levels of firm performance in the South African ICT sector

Hypothesis 3: The EO dimension of risk-taking is positively related with higher levels of firm performance in the South African ICT sector

Hypothesis 4: The EO dimension of pro-activeness is positively related with higher levels of firm performance in the South African ICT sector

Hypothesis 5: Higher levels of entrepreneurial culture is positively related with higher levels of firm performance in the South African ICT sector

4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The research relies on a quantitative cross-sectional empirical approach which is based on primary data sources. The context of the study is the South African ICT industry. By focusing on a single industry sector, a greater homogeneity of context is achieved which addresses the concerns of broad applicability versus perfect suitability for narrower groups. Studies across industries often produce results that apply to all while they at the same time apply to none (Davidsson 2004). Consequently the focus is on a single industry. The important issue about sampling, in general, is not statistical but theoretical representativeness, i.e., the elements in the sample represents the type of phenomenon that the theory makes statements about (Davidsson 2004).

4.1 Sampling and data collection

The population of this research study comprises of all ICT companies listed in the in South African ICT sector review 2009/2010. The research study used a database which has listed and non-listed ICT companies operating in all provinces in South Africa.

Company data was obtained from the ITWEB website (www.itweb.co.za) and the South African ICT sector review 2009/2010 (Esselaar et al. 2010).

A research design involving a web-based self-reporting survey instrument was used. The survey was distributed via 'Surveymonkey', which was selected principally because of its functionality and more importantly since it was considered suitable for the target population who are likely to use online resources regularly. The sampling frame included firms such as web designers, cellular phone assembling, computer networking, data services, cabling, to cellular network providers. The questionnaires were sent through a web-link (www.surveymonkey.co.za) to ICT managers, directors, CEOs and supervisors in terms of the sampling frame. Consistent with previous studies (Wiklund 1999) control variables included, firm age and firm size. The survey was sent to 267 firms, with a response rate of 42.7% obtained. A final sample size of n=114 firms was deemed to be appropriate for an empirical survey based study.

4.2 The research instrument

The survey collected quantitative, closed-ended questions. The questionnaires used the 5-point Likert scale, which has been used previously in similar studies (Monsen & Boss 2009; Wakkee, Elfring & Monaghan 2010). The questionnaire was structured to etermine levels of the EO dimensions, entrepreneurial culture and firm performance among the sample of firms selected.

The content section of the instrument was designed to reflect the EO dimensions of innovation, risk-taking and proactiveness, consisting of nine items. Many alternative EO conceptualisations are to be found (Brown, Davidsson & Wiklund 2001), and have demonstrated some usefulness, however as Davidsson (2004) suggests using the existing EO measure has the advantage of theoretical backing, a multidimensional construct, and theoretically meaningful relationships established in previous studies, thus allowing for more refined knowledge to evolve.

The EO dimensions have evolved from the ENTRESCALE, which was derived at by identifying the innovative and proactive disposition of managers at firms. This scale initially developed by Khandwalla (1977), refined by Miller and Friesen (1983), and Covin and Slevin (1989), has been found to be highly valid and reliable at cross-cultural levels (Knight 1997).

Entrepreneurial culture was measured in terms of the eight items highlighted in the literature review section (Morris et al. 2008). These items have been found to represent the core construct of entrepreneurial culture, and have been previously associated with higher performing firms (Lumpkin & Dess 1996; Morris et al. 2008; Venter et al. 2008). Both of these instruments utilized in different studies were scrutinised for construct validity and reliability, and based on the mere weight of writing supporting the application of these instruments confirms that their use is justified.

Considering that evidence for discriminant and convergent validity of measures already exists, only the reliability of scale was re-tested for this sample of respondents. Internal consistency reliability coefficients, as measured by Cronbach's coefficient, were for the EO dimension of innovation = 0.80; risk-taking = 0.81; pro-activeness = 0.84; and for entrepreneurial culture = 0.88, all of which are well within the accepted norm of 0.70 (Nunnully 1978).

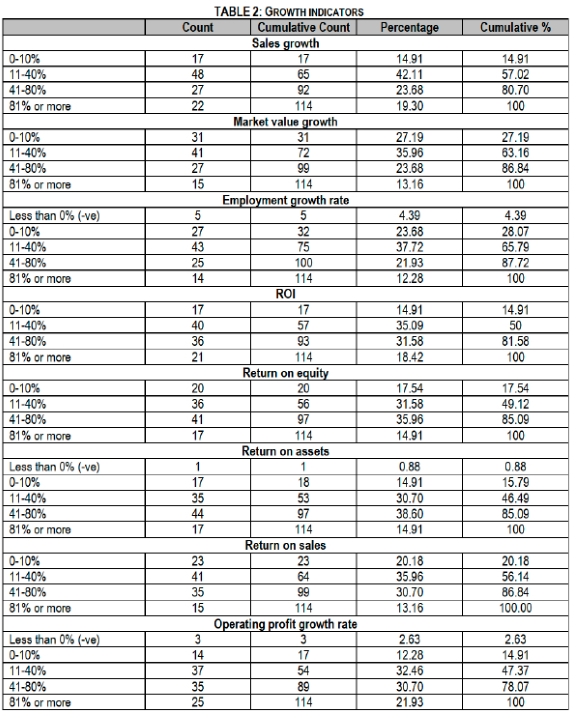

Organisational performance was measured in terms of various growth indicators. Although there is no consensus on the appropriate measure of firm growth, entrepreneurship researchers have pointed to multidimensional nature of growth as the crucial indicator of entrepreneurial success (Covin & Slevin 1997; Low & MacMillan 1998). Consequently, sales performance, return on assets (ROA), employment growth, return on sales, return on equity (ROE), return on investment (ROI), and operating profit were used to measure financial performance. The respondents were asked to consider firm performance in terms of these indicators over a period of five years.

In order to ensure the instrument had face and content validity, a preliminary analysis via a pilot test was undertaken. A pilot test was conducted by sending the instrument to a leading ICT firm - Vodacom SA, where errors in the survey, such as "allow one answer per column", were corrected. This process allowed the researcher to refine the questionnaire design. This procedure ensured that the respondents had no difficulties in answering the questions and there was no problem in recording the data.

4.3 Data analysis techniques

Data analysis was conducted, where descriptive and inferential statistics were calculated using the STATISTICA software system, version 10 (StatSoft 2011). Since firm performance was measured with multiple ordinal variables, in order to analyse these variables in relation to EO and culture, three performance categories (Poor, Moderate and High) were developed to make it more practical for analyses and presentation.

A logical test was done to check the overall company performance. The scale numbers of Ys and 2's were counted for each company - these were regarded as 'poor performance'. The scale number 3's was manipulated and these were regarded as 'moderate performance'. The scale number of 4's and 5s were manipulated and these were regarded as 'high performance'. Multivariate and univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) tests were used to test the hypotheses. Box and Whisker Plots were additionally drawn to scrutinize the hypotheses.

5 DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

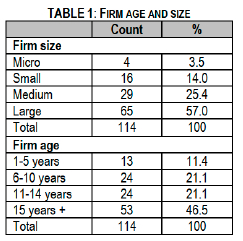

Table 1 refers to firm age and size, where it is observed that the majority of respondents was large (57%) and established (46.5%) companies.

Based on the grouping of firm performance as described above in the data analysis section and in Table 2, the groups were compared across the EO dimensions and culture simultaneously in terms of hypothesis 1.

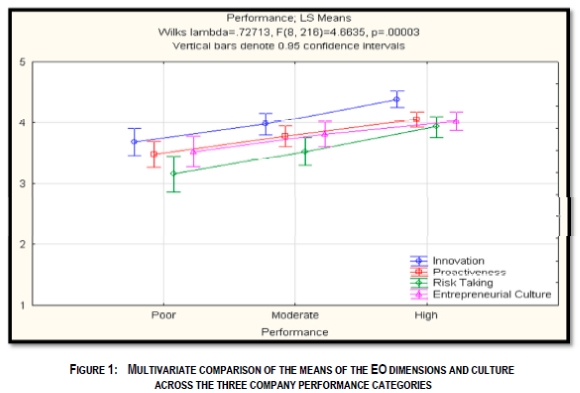

This multivariate test was conducted to test the means of multiple independent variables, compared to different groups of dependent variables (Cooper & Emory 1995). Figure 1 shows the results obtained after running the multivariate test simultaneously across variables. This multivariate comparison is an overall comparison, at the 5% level of significance, that controls the experiment-wise compounding of the Type 1 error that would have occurred had four univariate comparisons been carried out using a 5% level of significance.

A significant difference between the EO dimensions, entrepreneurial culture and the different firm performance groups was observed when running the multivariate test. A p value (p = 0.00003) was obtained which is significant at 95% confidence level. From this, the null hypothesis is rejected and the alternative hypotheses (as formulated in this study) can be supported. This empirical test confirms that there is a significant association between EO dimensions, culture and company performance.

5.1 Hypotheses Testing Results

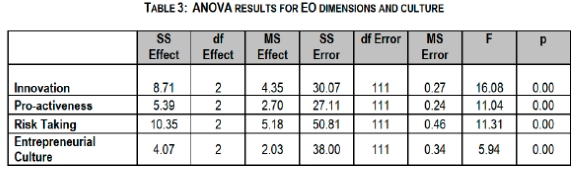

Following the multivariate tests, each hypothesis was tested independently in line with formulations, which entailed conducting univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) tests. All of the one-way ANOVA tests were significant at the p < .05000 level, see results in table 3.

However, in order to establish the source of the significant difference between the means of these scores, the Scheffe test was performed to compare the means of the different performance groups relevant to each independent variable. The results show that there is no significant difference between 'poor and moderate firm performance' groups. Hence these two groups were combined into a single group representing the 'poor/moderate performance' category.

These groupings were then used for the remainder of the data analysis. Additionally, t-tests were conducted to compare the means of these two firm performance groups to investigate if they are significant in terms of the hypothesized relationships. The results from the t-tests satisfied the conditions for homogeneity of variance between the groups and, moreover, revealed significant mean differences.

When the values of significance levels were considered for directional t-tests, all four t-tests on innovation, pro-activeness, risk taking and culture were significant at the 0.1% level. Moreover, the pair-wise means were consistently higher for the 'high performance' group when compared to the 'poor/moderate performance' group. These results provide preliminary support for the hypotheses.

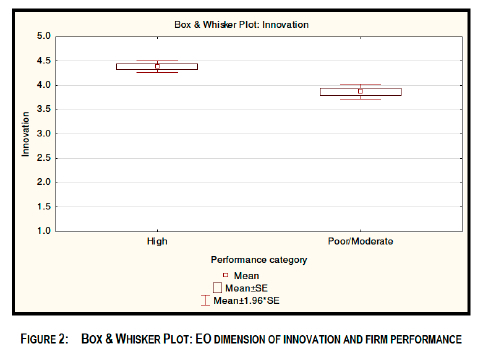

In terms of hypothesis 2, the association between the EO dimension of innovation and company performance was tested using ANOVA, which compares the means of different groups. The results indicate a significant difference between the groups, rather than within the groups. The significance level of p < 0.05 was obtained, which provides support for hypothesis 2. A t-test was then performed for the two firm performance groups - (1) high performance and (2) poor/moderate performance. In terms of the EO dimension of innovation, a significant difference between the means of these two groups was detected at the p < 0.05 level.

A box and whisker plot was then plotted to check for the range of the minimum, first quartile, median, second quartile and maximum values (Cooper & Emory 1995). The outliers were checked through this method. The observed results from Figure 2 of the box-whisker plot depicts that higher levels of EO innovation are associated with the 'high performance' group and organisations with lower levels of innovation are associated with the 'poor/moderate performance' group. These associations are significant at p < 0.05 level, which adds support to hypothesis 2. Moreover there was no overlapping observed on the box and whisker plot and there is a clear separation between the 'high and poor/moderate performing' groups. This indicates that these groups are significantly different.

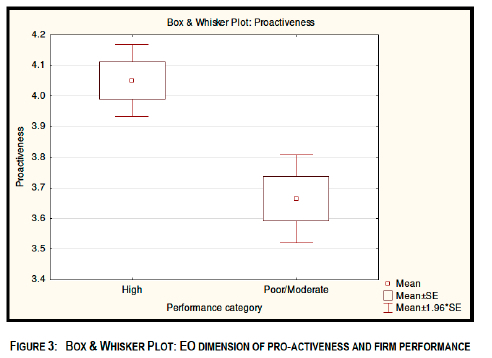

In terms of hypothesis 3, the same procedure was conducted. The ANOVA test results show significant difference between the groups, rather than within the groups, at the p < 0.05 level, which supports hypothesis 3. Similarly the t-test results reveal a significant difference between the means of these two groups.

The box and whisker plot shown in Figure 3 was calculated to test the level of pro-activeness in relation to the two performance groups. A significant difference at the p < 0.05 level, providing support for hypothesis 3, between the two performance groups was observed when the mean levels of pro-activeness were examined. The observed results of the box-whisker plot depicts that higher levels of pro-activeness are associated with the 'high performance' group, and organisations with lower levels of pro-activeness tend to have 'poor/moderate performance'.

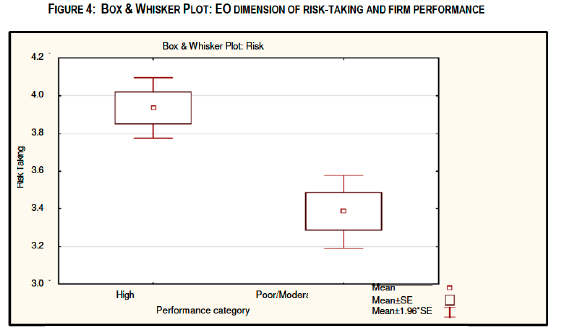

To test hypothesis 4 in terms of the association between the EO dimension of risk-taking and company performance, the same procedure was used with ANOVA. Results show a significant difference between the groups, rather than within the groups, at the p < 0.05 level which adds support to hypothesis 4.

Similarly, the t-test result indicates a significant difference between the means of these two groups. The box and whisker plot is shown in Figure 4, where a significant difference between the two firm performance groups was observed. Firms with higher levels of risk taking are associated with the 'high performance group'. This association is significant at p < 0.05 level and lends support to hypothesis 4.

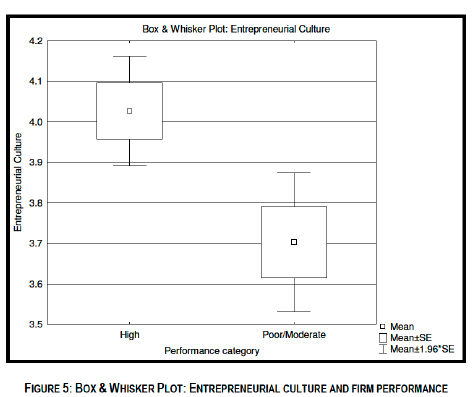

In terms of hypothesis 5, the relationship between entrepreneurial culture and company performance, both the ANOVA and t-test results show significant differences between the groups at the p < 0.05 level, supporting hypothesis 5.

The box and whisker plot, shown in Figure 5, represents the level of entrepreneurial culture in relation to the two performance groups. The significant difference between the two performance groups was observed where companies with higher levels of entrepreneurial culture are associated with the 'high performance' group, lending support to hypothesis 5.

6 CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to investigate possible links between the EO dimensions, entrepreneurial culture and company performance in the ICT sector. Building on previous CE research the study hypothesised the importance of entrepreneurial behaviour in terms of innovation, risk-taking, pro-activeness, and culture in relation to business performance (Zahra & Covin 1995; Yiu & Lau 2008).

The empirical findings emanating from this study show that the EO dimensions and culture have a significant and positive relationship with higher company performance, adding support to all of the hypotheses. These findings are in line with previous research (Steffens et al. 2009; Lumpkin & Dess 1996) where the EO dimensions were related to higher company performance. Innovation tends to lead to higher organisational performance, and innovative companies are able to perform well, even when they encounter a turbulent environment. This turbulent environment tends to trigger more demand for innovation and this, in turn, leads to high performance.

Firms that take innovation seriously and implement their new ideas are able to prosper and perform better. Innovative firms are those that invest heavily in research and development, as well as new product development. They have leaders with clear vision, who are able to integrate innovation and creativity into the business strategy. Miller (1983) stated that the firm's ability to be a first mover gives it an opportunity to exploit future opportunities ahead of competitors. A company's aggressiveness in pursuit of market opportunities offers the firm an opportunity to improve its performance.

In the ICT sector, environmental dynamism is relatively high due to fast-changing electronic devices, computer software, requirements for fast data throughput and overall technological changes (Esselaar et al. 2010). This type of environmental dynamism forces firms to be innovative and proactive in introducing new products, so that they capture better market share and gain competitive advantage over their rivals. From the results of this study, it is clear that innovation and pro-activeness are required for a firm to be associated with high performance.

Similarly risk taking is required in terms of bold actions with regard to introducing new products, risk projects and other activities with uncertain returns (Wang 2008). Risk taking allows managers to tolerate risk and implement a culture of not punishing employees who try and fail (Moreno & Casillas 2008). An entrepreneurial culture allows individuals to implement new ideas and take risks, which is a key element for enhanced business performance. This risk-taking dimension of EO and entrepreneurial culture were found to be crucial elements in stimulating firm performance in previous studies (Zahra & Covin 1995), and are supported with the results from the present study.

All the dimensions of EO are central to understanding the entrepreneurial process, although they may occur in different combinations, depending on the type of entrepreneurial opportunity the firm pursues. EO is manifested across the organisation through an entrepreneurial culture. In conclusion, to argue that firms must learn to act entrepreneurially is no longer a novelty and the reasons they could benefit from doing so are becoming more evident as a result of mounting empirical evidence from studies such as the present one.

7 RECOMMENDATIONS

In order to maintain or improve performance across a host of financial indicators, it is recommended that ICT companies in South Africa consider introducing and implementing EO through the dimensions of innovation, pro-activeness and risk taking into their businesses. Moreover entrepreneurial culture has been shown to be an important link to performance and without it, employees with a sense of innovation, risk taking and pro-activeness may well experience difficulties.

Since the ICT industry is a fast-growing sector it seems a company must first identify efficient means of being more pro-active, innovative and able to take bold action in implementing new projects in an uncertain environment with the intention of capturing new markets. Managers adopting EO and instilling an entrepreneurial culture will benefit financially, as the implications relate to the profitability and competitiveness of the firm. Intrapreneurial organisations are increasingly judged according to how a firm uses technology and innovation to achieve its objectives, such as maximising profits, gaining market share, creating niche markets or adding value for stakeholders (Bosma, Stam & Wennekers 2010).

The study provides guidance to managers and company leaders interested in undertaking intrapreneurial practices and the links to firm performance. Correspondingly, the result provides direction to employees seeking to engage in intrapreneurship and gives them a fair indication of EO practices which are required. Some specific recommendations are:

• An entrepreneurial culture is required for EO to flourish.

• Increase the number of innovation sponsors (champions) by encouraging managers to help employees getting their work done by removing obstacles and roadblocks.

• Establish a culture more tolerant toward risks, mistakes and failure by allowing employees to take calculated risks and practical experimentation. Accept mistakes and failure as a learning process and learning necessitates mistakes.

• Make innovation the cornerstone of developmental programmes. Develop a set of metrics to track innovation inputs (such as the number of hours devoted to innovative projects), throughputs (such as the number of new ideas entering the company's innovation pipeline), and outputs (such as the cost advantages gained from innovative breakthroughs).

• Institutionalize EO in the firm through which resources are made readily available and accessible in pursuance of new ideas and opportunities.

8 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The research focused on aspects of EO and culture which is often complemented by other variables not accounted for in this study, which may however impact organisational performance, such as and company size (Huse et al. 2005). Future studies may include variables such as company structure, marketing strategy, policies, operations processes, and international activities (Mazzarol & Reboud 2006). Moreover future research could adopt a longitudinal design since a cross-sectional approach as employed in this study loses the dynamic aspects of entrepreneurial behaviour, and prevents conclusions about causal relationships to be drawn among the variables.

REFERENCES

AGCA V, TOPAL Y & KAYA H. 2009 Linking intrapreneurship activities to multidimensional firm performance in Turkish manufacturing firms: an empirical study. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1-19. [ Links ]

ANDERSON B S, COVIN JG & SLEVIN DP. 2009. Understanding the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strategic learning capability: an empirical investigation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3:218-240. [ Links ]

ANTONCIC B & HISRICH RD. 2001. Intrapreneurship: construct refinement and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5):495-527. [ Links ]

ANTONCIC B & HISRICH RD. 2004. Corporate entrepreneurship contingencies and organisational wealth creation. Journal of Management Development, 23(6):518-550. [ Links ]

BOSMA N, STAM E & WENNEKERS S. 2010. Intrapreneurship - an international study. EIM Research Report Intrapreneurship. Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs. [ Links ]

BROWN T, DAVIDSSON P & WIKLUND J. 2001. An operationalization of Stevenson's conceptualisation of entrepreneurship as opportunity-based firm behaviour. Strategic Management Journal, 22:953-968. [ Links ]

BURNS P. 2004. Corporate entrepreneurship: building an entrepreneurial organization. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

COOPER RD & EMORY CW. 1995. Business research methods. 5th ed. Chicago: Irwin. [ Links ]

COVIN JG & MILES MP. 1999. Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3):47-63. [ Links ]

COVIN JG & SLEVIN DP. 1989. Strategic planning of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10:75-87. [ Links ]

COVIN JG & SLEVIN DP. 1991. A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behaviour. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16:7-26. [ Links ]

COVIN JG & SLEVIN DP. 1997. High growth transitions: theoretical perspectives and suggested directions. In SEXTON DL & SMILOR RW (eds). Entrepreneurship pp. 99-126. [ Links ]

COVIN JG & SLEVIN DP. 2002. The entrepreneurial imperatives of strategic leadership. In HITT MA, IRELAND RD, CAMP SM & SEXTON DL. (eds.) Strategic entrepreneurship: creating a new mind-set. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. pp. 309-327. [ Links ]

COVIN JG & MILES JP. 1999 Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3):47-63. [ Links ]

DAVIDSSON P. 2004. Researching entrepreneurship. International Studies in Entrepreneurship. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

DESS GG, IRELAND RD, ZAHRA SA, FLOYD SW, JANNEY JJ & LANE PJ. 2003. Emerging issues in corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 29: 351-378. [ Links ]

DESS GG LUMPKIN GT & MCGEE JE. 1999. Linking corporate entrepreneurship to strategy, structure, and process: suggested research directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Winter:85-101. [ Links ]

DRUCKER P. 1979. The practice of management. London. Pan. [ Links ]

ESSELAAR S, GILLWALD A, MOYO M & NAIDOO K. 2010. South African ICT sector performance review. 2009/2010. Towards evidence-based ICT policy and regulation. Volume Two: Policy Paper 6. [ Links ]

GRIES T & NAUDE W. 2010. Entrepreneurship and structural economic transformation. Small Business Economics, 34:14-29. [ Links ]

GROENEWALD D. VAN VUUREN J. 2011. Conducting a corporate entrepreneurial health audit in the South African short term insurance businesses. Journal of Contemporary Management, 8:1-33. [ Links ]

HAYTON C, GEORGE G & ZAHRA SA. 2002. National culture and entrepreneurship: a review of behavioural research. Entrepreneurship Theory And Practice, Summer: 33-52. [ Links ]

HOFFMANN EC & MARCUS JSF. 2011. Private versus public sector administrative executive: dichotomy or synergy, Journal of Contemporary Management, 8:95-122. [ Links ]

HUSE M, NEUBAUM DO & GABRIELSSON J. 2005. Corporate innovation and competitive environment, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1 (3),313-333. [ Links ]

IRELAND DR, COVIN JG & KURATKO DF. 2009. Conceptualizing corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(1),19-46. [ Links ]

ITWEB. 2011.URL: http://www.itweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_sobi2&sobi2Task=searchListall&Itemid=176. [ Links ]

KNIGHT GA. 1997. Cross-cultural reliability and validity of a scale to measure firm entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Business Venturing, 12: 13-225. [ Links ]

KREISER PM, MARINO LD & WEAVER MK. 2002. Assessing the psychometric properties of the entrepreneurial orientation scale: a multi country analysis. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Spring:71-94. [ Links ]

KREISER PM & DAVIS J. 2010. Entrepreneurial Orientation and firm performance: the unique impact of innovativeness, pro-activeness, and risk- taking. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 23(1),39-51. [ Links ]

KURATKO DF. 2002. Corporate entrepreneurship. New York: Harcourt. [ Links ]

KURATKO DF, IRELAND RD & HORNSBY JS. 2001. Improving firm performance through entrepreneurial actions: corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Academy of Management, 15:60-71. [ Links ]

KHANDWALLA PN. 1977. The design of organizations. New York: Harcourt. [ Links ]

LANDSTROM H, CRIJNS H, LAVEREN E & SMALLBONE D. 2008. Entrepreneurship, Sustainable Growth and Performance. 2nd ed. London: Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

LOW M & MACMILLAN I. 1998. Entrepreneurship: past research and future challenges. Journal of Management, 14:139-161. [ Links ]

LUMPKIN GT & DESS GG. 1996. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21:135-166. [ Links ]

LUMPKIN GT & DESS GG. 2001. Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: the moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. Journal of Business Venturing, 16:429-451. [ Links ]

LUMPKIN GT, COGLISER CC & SCHNEIDER DR. 2009. Understanding and measuring autonomy: an entrepreneurial orientation perspective. Entrepreneurship and Theory in Practice, 33(1):47-69. [ Links ]

MAZZAROL T & REBOUD S. 2006. The strategic decision making of entrepreneurs within small high innovator firms. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2(2):261-280. [ Links ]

MILLER D. 1983. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29:770-791. [ Links ]

MILLER D & FRIESEN PH. 1983. Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: two models of strategic momentum. Strategic Management Journal, 3:1 -25. [ Links ]

MONSEN E & BOSS RW. 2009. The Impact of strategic entrepreneurship inside the organisation: examining job stress and employee retention. Entrepreneurship and Theory in Practice, 33(1):71-104. [ Links ]

MORENO A & CASILLAS JC. 2008. Entrepreneurial orientation and growth of SMEs: a casual model. Entrepreneurship and Theory in Practice, 32(3):507-528. [ Links ]

MORRIS MH, KURATKO DF & COVIN JG. 2008. Corporate entrepreneurship and innovation. Cincinnati, OH: Thomson/Southwestern. [ Links ]

MORRIS MH & KURATKO DF. 2002. Corporate entrepreneurship. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt. [ Links ]

NUNNALLY JC. 1978. Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PERKS S, MUTETI JK, PIETERSEN J & BOSCH JK. 2010. Strategic implications of the drivers of e-business implementation in developing countries. Journal of Contemporary Management, 7:519-548. [ Links ]

PHAN PH, WRIGHT M, UCBASARAN D & TAN WL. 2009. Corporate entrepreneurship: current research and future directions. Journal of Business Venturing 10:10-16. [ Links ]

PIENAAR JJ & DU TOIT ASA. 2009. Role of the learning organisation paradigm in improving intellectual capital. Journal of Contemporary Management. 6:121-137. [ Links ]

PREECE SB, MILES G & BAETZ MC. 1998. Explaining the international intensity and global diversity of early-stage technology based firms, Journal of Business Venturing, 14:259-281. [ Links ]

RAUCH A, WIKLUND J, LUMPKIN GT & FRESE M. 2009. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: an assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3):761 -787. [ Links ]

SCHUMPETER JA. 1934. The theory of economic development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

SEBORA TC & THEERAPATVONG T. 2009. Corporate entrepreneurship: a test of external and internal influences on managers' idea generation, risk taking, and pro-activeness. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 5(1): 1-20. [ Links ]

STATSOFT. 2011. STATISTICA (data analysis software system): Version 10. [URL: www.statsoft.com] [ Links ]

STEFFENS P, DAVIDSSON P & FITZSIMMONS J. 2009. Performance configurations overtime: implications for growth- and profit oriented strategies. Entrepreneurship and Theory in Practice, 33(1):125-148. [ Links ]

URBAN B. 2010a. A focus on networking practices for entrepreneurs in a transition economy. Transformations in Business and Economies, 9(3)21: 52-66. [ Links ]

URBAN B. 2010b. EO and TO at the firm level in the Johannesburg area. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(1):1-9. [ Links ]

URBAN B & OOSTHUIZEN C. 2009. Empirical analysis of corporate entrepreneurship in the South African mining industry. Journal of Contemporary Management, 6:170-192. [ Links ]

VAN VUUREN J, GROENEWALD D & GANTSHO MSV. 2009. Fostering innovation and corporate entrepreneurship in development fiancé institutions. Journal of Contemporary Management, 6:325-360. [ Links ]

VENTER A, RWIGEMA H & URBAN B. 2008. Entrepreneurship: theory in practice. 2nd ed. Cape Town: Oxford. [ Links ]

VOZIKIS GS, BRUTON GD, PRASAD D & MERIKAS AA. 1999. Linking corporate entrepreneurship to financial theory through additional value creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(2):33-43. [ Links ]

WAKKEE I, ELFRING T & MONAGHAN S . 2010. Creating entrepreneurial employees in traditional service sectors. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(1):1 -21. [ Links ]

WANG CL. 2008. Entrepreneurial orientation, learning orientation, and firm performance. Entrepreneurship and Theory in Practice, 32(4), 635-654. [ Links ]

WIKLUND J. 1999. The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(1):37-48. [ Links ]

WRIGHT M, HMIELESKI M, SIEGEL DS & ENSLEY MD. 2007. The role of human capital in technological entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31 (6):791- 807. [ Links ]

YIU DW & LAU C. 2008. Corporate entrepreneurship as resource capital configuration in emerging market firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(1):37-57. [ Links ]

ZAHRA SA & COVIN JG. 1995. Contextual Influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10:43-58. [ Links ]

ZAHRA AS & GARVIS MD. 1998. International corporate entrepreneurship and firm performance: the moderating effect of international environmental hostility. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(1):469-492. [ Links ]

ZAHRA SA, NIELSEN AP & BOGNER WC. 1999. Corporate entrepreneurship knowledge, and competence development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3):169-189. [ Links ]

ZAHRA SA & COVIN G. 1995. Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(2):43-58. [ Links ]