Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.8 no.1 Meyerton 2011

RESEARCH ARTICLES

A contemporary management perspective of the concept "a culture of learning"

FH WeeksI; RV WeeksII

IUniversity of South Africa

IIUniversity of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Increasingly researchers attest to the reality of a globally interconnected world, where change has become endemic. Thomas and Brown (2011:17) present a worldview of learning in the 21st century, suggesting learning is "around us, everywhere" and term the phenomenon to be the "new culture of learning". The discourse in this paper is centred on drawing a comparative analysis of traditional and contemporary management perspectives, as they relate to engendering a culture of learning within institutions in order to deal with the challenges presented by a 21st century of unprecedented contextual complexity. The methodology adopted in compiling this paper is analytically-descriptive in nature and is based on a multi-disciplinary literature study. The literature analysis revealed a fundamental difference between an "ordered" and "complex" system approached in engendering a culture of learning. An important finding stemming from the literature study is that traditional ordered paradigms relating to engendering a culture of learning in contemporary institutions may no longer be effective and the adoption of a complex systems approach is suggested.

Key phrases: Complex systems theory; Culture of learning; Cynefin Framework; Learning organisation; Organisational culture

1. INTRODUCTION

"In our view, the kind of learning that will define the twenty-first century is not taking place in a classroom - at least not in today's classroom. Rather, it is happening all around us, everywhere, and it is powerful. We call this phenomenon the new culture of learning, and it is grounded in a very simple question: What happens to learning when we move from the stable infrastructure of the twentieth century to the fluid infrastructure of the twenty-first century, where technology is constantly creating and responding to change?"(Thomas & Brown 2011:17)

It is suggested by Peters (2003:17) that "if you don't like change, you're going to like irrelevance even less". Increasingly, change within a highly networked global context has become endemic, it often emerges without any real warning, has a very significant impact on communities and their institutions, and requires new innovative thought leadership for dealing with the consequences. It in effect necessitates a real world learning experience that engenders new paradigms for dealing with what Peters (2003:26) refers to as the mess.

Peters (2003:27) issues a warning to those involved in manage their institutions through this mess, namely: "Beware the champions of order ... Beware those who prescribe 'rules'... rules that will (supposedly) vault you into the ... Pantheon of the Gods". It is a viewpoint that resonates with the need for a new culture of learning alluded to by Thomas and Brown (2011:17). Implied is a context of complexity, where yesterday's paradigms of management are no longer effective for dealing with the emergent contextual reality or mess of today. Within such a context learning becomes a never ending life long experience.

Friedman (2006:5) captures the essence of the reality that has given rise to the context that Peters (2003:17) refers to as the mess in his disclosure to his wife when he stated that "I think the world is flat". The basis for his contention resides within the new age of global connectivity, or in more contemporary management terms, a networked, interconnected and integrated global society (Peters 2003:6,10,17). The flat-world platform is the product of a convergence of technologies enabling people to collaborate, compete, interact and learn without the constraints of geographical boundaries. It is, however, also a context that Taleb (2007:xix) describes as being characterised by Black Swan logic, where "what you don't know" is far more relevant than that "you do know".

Here the accent is certainly on gaining an ability to learn from so called Black Swan events that emerge quite unexpectedly and have a significant impact on communities. Typical events cited by Taleb (2007:xix) are the 9/11 terrorist attack on New York and the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004. In more recent terms events such as the Iceland volcanic eruption that disrupted European air traffic; the Japanese Tsunami that gave rise to the Fukushima nuclear disaster; and the global economic meltdown that left its shadow on many a nations' economy are deemed to be typical Black Swan events.

Kiechel (2010:2) in a similar metaphorical sense refers to these unforeseen, unexpected and high impact events that are emerging with increasing intensity, as the "horsemen of the corporate apocalypse". The metaphor resonates with a biblical account, found in the book of Revelations, where four horsemen unleash unparalleled havoc and catastrophe on the world. The picture that emerges from this discourse is not just one of a mere four, but a significant number of metaphorical horsemen or Black Swan events, engendering an emergent onslaught on communities and their institutions. The need for never ending learning in dealing with the changing complex nature of the emergent landscape that shapes the life world of contemporary communities and institutions is created, which in turn implies the need for a well established culture of learning. To echo Thomas and Brown (2011:18) "this new culture of learning can augment learning in nearly every facet of education and every stage of life. It is a core part of what we think of as 'arc of life' learning, which comprises the activities in our daily lives that keep us learning, growing, and exploring".

The brief introductory discourse attests to two fundamentally different life worlds that confront contemporary institutions. The first is a traditional relatively ordered life world where cause effect relationships are predictable, and consequently experiential learning serves as a means for dealing with the future. The second is far more complex where, at best, cause and effect relationships are retrospectively coherent and are seldom repeatable. In refereeing to retrospective coherence Kurtz and Snowden (2003:469) define it in terms of "emergent patterns that can be perceived but not predicted". A complex context, as is suggested in this paper, necessitates what Thomas and Brown (2011:18) refer to as "arc of life" learning.

In the ensuing discussion the two life world ontology's will be explored from a management perspective, with specific reference to the need for establishing a culture of learning. The concepts "culture of learning", "organisational learning" and "the learning organisation" are then clarified. With the conceptual clarity serving as a source of information and reference the management implications of the necessity to deal with sense and decision making in complicated and complex contexts are explored, particularly as it relates to the need for and the nurturing of a culture of learning. The literature research, the groundwork of the paper, is analytically-descriptive and multi-disciplinary in nature. The latter was deemed essential in view of the very limited management literature relating to the management of institutions within contexts of simultaneous order and complex change. The objective therefore was to learn from the insights gained from diverse disciplines; in order to see if any emergent management insights or views could be determined that would collectively assist the management of institutions to deal more effectively with the complex issues involved.

2. CONCEPT CLARIFICATION

2.1 COMPLICATED AND COMPLEX CONTEXTS

Sargut and McGrath (2011:70) are of the view that contextual complexity, which communities and institutions need to deal with, has significantly increased over the past 30 years. They acknowledge that it has always in a sense existed, in which life has always featured the unpredictable, the surprising, and the unexpected. It is, however, suggested by the researchers that complexity has become far more prevalent in modern-day contexts (Sargut & McGrath 2011:70). According to Sargut and McGrath (2011:70) the importance of this observation stems from the fact that "if you manage a complex organization as if it were just a complicated one, you'll make serious, expensive mistakes". Cilliers (1998:3) is another researcher who draws a distinction between complicated and complex systemic contexts. Cilliers (1998:3) suggests that while complicated systems may well have a large number of interacting components and perform sophisticated tasks, they can be analysed accurately, while complex systems tend to be unpredictable.

Following a similar trend of thought, Malherbe, Scanell and van der Merwe (2011:66-2) citing Woermann, conclude that "whereas a complicated system may initially look complex (due to the large number of components that may constitute the system, and/or the sophistication of the tasks that the system can perform), the hallmark of a complicated system is that - unlike a truly complex system - we can figure it out". Van Rensburg (2011:19-3), in commenting on the difference between complicated and complex systems, specifically accentuates the fact that complicated systems "do not have the characteristic of being stochastic". Implied from the descriptions of complicated systems is a sense of order.

Kurtz and Snowden (2003:468) concur that in ordered contexts cause and effect relationships are generally linear, empirical in nature, and not open to dispute. Within an ordered context cause and effect relationships can not only be determined, but also extrapolated to predict the outcomes of future events or trends. Kurtz and Snowden (2003:468) conclude that an ordered context is the domain of systems thinking, the learning organisation, and the adaptive enterprise, all of which are too often confused with complexity theory.

Sargut and McGrath (2011:70) confirm that while complicated systems may consist of a large number of components they operate in patterned ways that can be predicted. Complex systems in contrast, claim Sargut and McGrath (2011:70), are imbued with features that may operate in patterned ways, but the interactions are constantly changing. It is these interactions that give rise to emergent unexpected and unpredictable outcomes. Sargut and McGrath (2011:70) advocate that three properties determine the complexity of an environment:

The first, multiplicity, refers to the number of potentially interacting elements. The second, interdependence, relates to the extent of the interconnection and interaction between the elements.

The third, diversity, this has to do with the degree of their heterogeneity.

The greater the multiplicity, interdependence and diversity, the greater the complexity of the context (Sargut & McGrath 2011:70). Complex contexts are described by Cilliers (1998:3) as constituting intricate sets of non-linear relationships and feedback loops that only engender certain aspects able to be analysed at a point in time. The non-linearity entails that small causes can have large results, and vice versa (Cilliers 1998:4; Sargut & McGrath 2011:70). In a slightly different sense Kurtz and Snowden (2003:464) describe complex contexts as one where a fascinating kind of order exists "in which no director or designer is in control but which emerges through the interaction of many entities". The important point that needs to be noted here is the reference to emergence as a characteristic of complex systems (Dimitrov 2003:1; Kurtz & Snowden 2003:464). From a culture of learning perspective it is pertinent to note that Malherbe et al. (2011:66-2) maintain that as a mechanism to cope with complexity and change educators increasingly emphasise teamwork, the ability to adjust to change, and what has been called "learning to learn". Axelrod and Cohen (1999:xii) refer to it as "trial-and-error learning".

Kurtz and Snowden (2003:464) assert that awareness of emergent order has, as yet, had comparatively little influence on mainstream theory and practice in management. Sargut and McGrath (2011:70) similarly conclude that while a great deal is known about navigating complexity, that knowledge hasn't permeated the thinking and mindsets of today's executives or the business schools that teach tomorrow's managers. Two problems consequently encountered in practice by managers in being confronted with complex contexts are that of unintended consequences and difficulty in making sense of situations (Sargut & McGrath, 2011:70). At the very core of complex contexts is the difficulty that is experienced, both in sense and decision making, as a result of emergent conditions that are unexpected, difficult to predict with any degree of accuracy, and even more pertinently they have a significant impact on communities and institutions.

As noted by Sargut and McGrath (2011:72), it is very difficult, if not impossible, for individual decision makers to gain a holistic view of an entire complex system, due to the vast array of cause and effect interactive relationships that give rise to emergent outcomes. A case in point is the prevailing sub-prime initiated economic meltdown that confronts governments, institutions and communities across the world. As has been painfully observed and learnt, while many people were aware of some of the elements, almost no one saw the complete picture or anticipated the consequences that stemmed from the emergent situation. This paper suggests that this is a reality in most Black Swan type of events that are emerging with increasing regularity and intensity.

2.2. CONCEPT CLARIFICATION: A CULTURE OF LEARNING AND A LEARNING ORGANISATION

Garvin, Edmondson and Gino (2008:109) attest to the fact that a culture of learning and the learning organisation are hardly new. The notion of organisational learning, according to Garvin et al. (2008:109), flourished in the 1990's, stimulated by Peter Senge's "The Fifth Discipline" and countless similar publications. This, suggest Garvin et al. (2008:109), resulted in a compelling vision of institutions skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge. It also gave rise to the belief that learning organisations would be able to adapt to the unpredictable more quickly than their competitors could (Garvin et al. 2008:109). The researchers then go on to observe that "unpredictability is very much still with us. However, the ideal of the learning organization has not yet been realized" (Garvin et al. 2008:110).

As seen from the introductory quotation, Thomas and Brown (2011:17) similarly question what happens to learning when we move from the stable infrastructure of the 20th century to the fluid infrastructure of the 21st century? These researchers are certainly not alone in questioning the realisation of a culture of learning in organisations and communities. For instance, former South African president Mbeki (1997:1) in his address at the launch of a culture of learning and teaching campaign at Fort Hare University, asserted that the country's education sector is characterised by too many words and little action in realising a culture of learning within the country's academic institutions.

The importance attributed to a culture of learning and learning organisations would seem to suggest a need for clarity as to what is exactly meant by the concepts. Sedibe (2006:27), however, in researching the concept culture of learning concludes that no uniformity exists as to the actual meaning attributed to the concept. In an attempt to gain clarity, Govender (2009:365) describes a culture of learning in terms of "an organisation skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and at modifying its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights". In so doing Govender (2009:364) additionally asserts that promoting a culture and institutionalising a learning organisation is a complex phenomenon.

Based on research undertaken, Govender (2009:366) observed that the concepts "organisational learning" and "a learning organisation" are frequently used synonymously and interchangeably. Organisational learning it would seem refers to a process through which an individual or groups representing the organisation employ enabling abilities to create a permanent cognitive behavioural change in the system (Govender 2009:366). Citing Garvin, Govender (2009:366) suggests that a learning organisation is one skilled in knowledge generation and its transfer as well as modifying behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights. The pivotal role of the process of knowledge generation is, according to Govender (2009:366), the foundation of the learning organisation paradigm. As noted, however, by the researcher the distinction appears to be very subtle and in practice they tend to be used in a very similar sense.

Roux, Murray and van Wyk (2009:v) claim that individual learning creates a learning organisation and identify four specific learning-related abilities as being essential, namely: acquiring knowledge from external resources; creating knowledge internally; transferring this knowledge; and adapting to apply this knowledge. In so defining the concept it will be seen that there is a strong correlation between their definition of the concept and that previously alluded to by Govender (2009:366). Roux et al. (2009:vi) further conclude that knowledge learning is a distinctly social process that results in change within both individuals as well as social systems. It is also emphasised by the researchers that "a pervasive learning culture is necessary for organisational learning to be effective" (Roux et al. 2009:vi). Nurturing a learning culture, suggests Roux et al. (2009:vi), involves shared visions and goals, establishing track records, finding the right people and applying appropriate leadership.

2.3 CONCLUSIONS DRAWN FROM DISCUSSION

Two pertinent conclusions can be drawn from this discussion. The first is that a culture of learning is deemed to be an imperative for learning to take place in order to engender what is termed to be a learning organisation. The second relates to learning as a social interactive process within an organisational context. In terms of the latter, Roux et al. (2009:vii) stress that knowledge creation is an active dynamic process of relating, thereby accentuating the social dynamic of organisational learning.

Rebelo and Gomes (2010:173) are two researchers who share the view that a culture of learning serves as an essential condition for organisational learning to take place and in so doing they cite an extensive list of researchers who support the contention. A culture of learning is described, by Rebelo and Gomes (2010:173) as one "orientated towards the promotion and facilitation of workers' learning, its share and dissemination, in order to contribute to organizational development and performance". In so defining the concept the researchers place emphasis on the concept as being a behavioural determinant and the outcome stemming from such behaviour, namely organisational development. The researchers suggest that an organisation, with a culture of learning, promotes and values individual learning that in turn, through a social process of sharing, gives rise to organisational learning (Rebelo & Gomes 2010:174). This learning, claims' Rebelo and Gomes (2010:173), is essential for dealing with global, dynamic and uncertain environments.

Citing numerous researchers, Rebelo and Gomes (2010:173) more specifically identify the convergent and distinguishing characteristics of a culture of learning, as one: focusing on people; embodying a concern for all stakeholders; stimulating experimentation; encouraging an attitude of responsible risk; engendering a readiness to recognise errors and learn there from; promoting open and intense communication; and encouraging co-operation, interdependence and a sharing of knowledge. Accentuated by the researchers is the reality of the culture being a construct of the people working within a specific contextual setting (Rebelo & Gomes 2010:176). They, however, also acknowledge that in spite of the importance attributed to the concept in the literature, there is still a lack of research in relation to what a culture of learning in fact is (Rebelo & Gomes 2010:174).

Following a similar trend of thought to that expressed, Roux et al. (2009:vi), Rebelo and Gomes (2010:173), and Sanz-Valle, Naranjo-Valencia, Jiménez-Jiménez and Perez-Caballero (2011:1) associate the culture of the organisation with both the fostering and inhibiting of technical innovation and organisational learning. Organisational learning and its knowledge generation is seen by the researchers as being essential in gaining an understanding of the consequences associated with changing environmental conditions that impact on institutions and their operations (Sanz-Valle et al. 2011:1). Also emphasised by the researchers is the fact that the culture itself serves as a behavioural determinant and consequently influences how the institution will respond to changing contextual conditions (Sanz-Valle et al. 2011:1). The researchers also note that "few studies have focused on the effect of culture on learning" (Sanz-Valle et al. 2011:1). They go on to further claim that organisational learning is considered to be a process of developing new knowledge and insights derived from employees common shared experiences within institutions, which has the potential to influence behaviour in responding to emergent conditions (Sanz-Valle et al. 2011:2,5).

In summary it may be concluded that a culture of learning would seem to constitute an imperative for learning to take place in groups, institutions and communities. The concept, more often than not, is described in terms of enabling conditions for learning to take place or the outcomes associated with the establishment of what is deemed to be a learning organisation. An important tenet that seems to emerge is the knowledge generation and transfer form a key element in organisational learning, and the establishment of a learning organisation. The need for the new knowledge generation and consequently organisational learning stems from the observation that increasingly institutions need to find new innovative solutions for dealing with the complexities associated with contextual change.

3. ORGANISATIONAL MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS IN FOSTERING A CULTURE OF LEARNING TO BE ABLE TO DEAL WITH CONTEXTUAL COMPLEXITY

Roux et al. (2009:xi) are of the view that the decision-making environment within contemporary institutions is dominated by uncertainties that are typical of complex systems and, as previously noted by Sargut and McGrath (2011:70), managing a complex organisation as if it were just a complicated one could well result in rather expensive mistakes. Seen in the context of the global economic meltdown the importance of this statement assumes a very definite consideration. This reality also suggests that managers dealing with sense and decision making need some form of indication to know if they are functioning within complicated, order or complex, emergent contexts. Their sense and decision making response within these differing contexts would need to be appropriate for the context they are operating in. Of equal importance is the need to engender a culture of learning in contemporary institutions, in order to find new innovative means of responding to what has been termed to be Black Swan events. In the ensuing discussion these management related aspects are explored.

It is postulated by Boulton (undated:20) that managers tend to preferably rely on methods predicated on certainty, with an intense focus on standardisation and measurement. Assumed management practice, according to Boulton (undated:20), is the notion that past best practice is a good predictor of the future, yet experience would seem to suggest that this is certainly not always the case. Why then, asks Boulton (Undated:20), do management keep basing practice on assumptions of certainty and predictability? The underlying reason, the researcher suggests, is one of a human psychological desire for certainty (Boulton Undated:21). Edgar Schein, in an interview by Coutu (2002:100), dismissed the popular notion that learning is fun and instead contended that radical relearning entails a sense of anxiety. Coutu (2002:100) concludes that most people consequently "just end up doing the same old things in superficially tweaked ways - practices that fall short of the transformational learning that most organizational experts agree is key to competing in the twenty-first century".

A change in management thinking and practice, so as to embrace the realities associated with contextual complexity would in the light of the preceding discourse seem to suggest the need for a learning organisation. Schein (in Coutu 2002:103104), however, asserts that "we don't know a lot about organizational learning", yet he suggests there is an inherent paradox surrounding learning in that anxiety inhibits learning, but it is also necessary if learning is going to take place at all. The basic principle according to Schein (in Coutu 2002:105) is that learning only takes place when survival anxiety is greater than learning anxiety. Evidence, it is argued by Schein (in Coutu 2002:105), is mounting that real change only occurs when institutions experience a very real threat of pain. It could be argued therefore that the consequences associated with Black Swan events and their impact on communities and corporations, could well serve as the anxiety catalyst for establishing a culture of learning in order to survive, what Peters (2003:26) terms to be, the mess. A factor confronting the contemporary institution and its managers is, as suggested by Hagel and Brown (2009:88), that their knowledge resources for dealing with institutional complexity is diminishing swiftly, implying a need for and an ability to rapidly refresh their knowledge stock for gaining an advantage in an age of near-constant disruption.

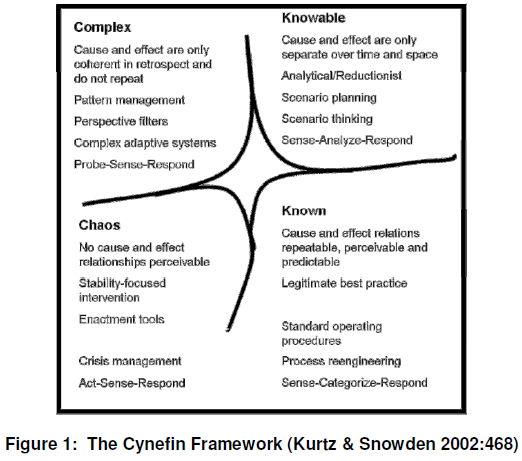

The discourse thus far has been on the difficulties executives experience in dealing with contextual complexity, but in practice there are also instances where operations are taking place in complicated, ordered contexts, where traditional best practice still has value. The Cynefin framework is essentially a sense and decision making framework and Snowden and Boone (2007:70) advocate its use so that executives can not only make better decisions, but also avoid the problems that arise when their preferred management style conflicts with that which is deemed appropriate for dealing with the contextual conditions that exist. Roux et al. (2009:9) concur that different knowledge and theory are required when operating in the different decision-making domains represented within the framework. The model constitutes four domains, two of which reside within what could be termed to be an ordered ontology, and the remaining two termed to be complex and chaotic are deemed to be within an unordered context. The four domains are diagrammatically present by Kurtz and Snowden (2002:468) by means of Figure 1. The diagrammatic presentation also suggests the appropriate response for sense and decision making in each of the domains concerned. The central domain of disorder applies when it is unclear which of the other four domains are prominent (Snowden & Boone, 2007:70).

The known and knowable domains respectively, are deemed to be ordered in that cause and effect relationships are generally predictable or can be determined (Roux et al. 2009:10). The consequential linearity implies that traditional best practice or good practices apply within the two domains concerned respectively. The typical sense, decision making and response characteristics associated with the respective domains are reflected in the Snowden and Boon (2007:72) diagrammatic presentation in Figure 1. Of particular relevance in terms of this paper is the fact that Kurz and Snowden (2003:468) contend that the knowable or complicated domain is characterised by systems thinking, the learning organisation, and the adaptive enterprise, all of which are often confused with complexity theory. Of further relevance is the assertion by Kurtz and Snowden (2003:72) that "it is important to note that by known and knowable we do not refer to the knowledge of individuals. Rather, we refer to things that are known to society or the organization, whichever collective identity is of interest at the time". This would seem to resonate with the definition attributed to a culture of learning by Rebelo and Gomes (2010:173), where the accent is on the collective or shared learning experience.

In the complex domain cause and effect relationships are only coherent in retrospect (Roux et al. 2009:10; Kurtz and Snowden 2003:469). Kurtz and Snowden (2003:469) describe the domain as "the domain of complexity theory, which studies how patterns emerge through the interaction of many agents". They further warn that in this space, structured methods that seize upon such retrospectively coherent patterns and codify them into procedures, will be confronted with new and different patterns for which they are ill prepared (Kurtz & Snowden 2003:469). Leaders who try to impose order in a complex domain, Snowden and Boone (2007:74) suggest, will fail. The researchers maintain that those who step back a bit and allow patterns to emerge so as to identify desirable patterns that can be stimulated and less desirable patterns that can be disrupted, will be more likely to succeed (Snowden & Boone 2007:74).

From a learning perspective Roux et al. (2009:31) argue that social systems exhibit complexity and a sense of unpredictability. Browaeys and Baets (2003:332) similarly argue that "culture is a complex process. This process does not go in good harmony with the traditional ways - based on the Cartesian epistemology" A Cartesian epistemology implies rational deductive processes, with underpinning linear causality as reflected in ordered space, which enables predictability that is deemed to form the very foundation on which traditional management thinking and practice is based. It could therefore be argued that a culture of learning, within a complex context, will converge from the host of social networking patterns that emerge from the interaction that takes place between the people involved. It is therefore implied that management at best can influence the culture of learning that emerges through their involvement in the interaction process. Roux et al. (2009:31) conclude that "the precise path taken to become a learning organisation, and hence the precise nature of that ability, will be determined by unpredictable emergent events, properties and behaviours (either directly or indirectly related to learning) typical of a complex system".

Seel (2000:2) is yet another researcher who would seem to endorse the view of the nurturing of a culture of learning as taking place within complex space. The emergent culture, according to Seel (2000:2) is the "result of the continuing negotiations about values, meanings and properties between the members of that organisation with its environment". Seel's (2000:2) description of emergent culture infers that culture change stems from conversation exchanges, which are generally not the focus in traditional culture change management initiatives directed at nurturing a specific typology of learning culture required (Tosti 2007:21), the actual outcomes of which cannot be predicted in practice as they are emergent in nature. It is also claimed by Schneider, Gunnarson and Niles-Jolly (1994:19) that culture changes emerge as a result of employees sharing interpretations of events through storytelling.

Snowden and Boone (2007:74) state that in the un-ordered chaotic domain "a leader's immediate job is not to discover patterns but to stop the bleeding... a leader must first act to establish order, then sense where stability is present and from where it is absent, then respond by working to transform the situation from chaos to complexity, where the identification of emergent patterns can both help prevent future crises and discern new opportunities". It would seem from the preceding discourse that contextual complexity, as reflected in various Black Swan events that have emerged over the space of time, present management of institutions and community leaders with intractable problems that cannot be dealt with on the basis of ordered space management approaches. Also apparent from the discussion is that a culture of learning is deemed to be essential for dealing with the situations and the consequences that emerge there from. Nurturing such a culture in itself would also best be dealt with in terms of a complex domain management response. Suggested management tools, by Snowden and Boone (2007:75) that can be applied within complex contexts are: open discussion; the setting of barriers; stimulation of attractors; encouragement of dissent and diversity; and the management of initial conditions, while monitoring for emergence.

A frequently encountered comment when dealing with contextual complexity is the need for soliciting alternative point of view and an openness to new ideas. For instance, Garvin et al. (2008:111) reason that the learning environment required is one characterised by a sense of psychological safety, an appreciation of different worldviews; openness to new ideas and a time for reflection. Apparent is the correlation that exists between the aspects raised by Snowden and Boone (2007:75) and that highlighted by Gavin et al. (2008:111).

Emergent trends and patterns that arise from Back Swan events are not always at first glance all that obvious and a time for their emergence and reflection thereon is required. As previously noted by Sargut and McGrath (2011:71) even small decisions can have surprising effects, thus the need for reflection. The researchers also noted that it is very difficult, if not, impossible for an individual decision maker to see an entire complex system (Sargut & McGrath 2011:72), thereby also insinuating the need for openness and alternative perspectives in order to learn and deal with the trends that emerge. Similarly it will be remembered that Schein (in Coutu 2002:105) had placed an emphasis on the anxiety experienced by employees and the need for a safe learning environment, an aspect also accentuated by Garvin et al. (2008:111).

Learning to cope with the emergent trends and the significant impact thereof on the operations of the institution requires trial-and-error learning (Axelrod & Cohen 1999:xii), as there is no guarantee that any intervention implemented by management will have the desired outcome. The picture that emerges from this brief reflection is one of a need for a culture of learning that, as suggested by Thomas and Brown (2011:37), thrives on complex change. Unlike the traditional sense of culture, which strives for stability, this emergent culture of learning, responds to its surroundings organically and consequently forms a symbiotic relationship with the environment (Thomas & Brown 2011:37).

Thomas and Brown (2011:37,48) capture the essence of what they term to be the new culture of learning in stating that "if the twentieth century was about creating a sense of stability to buttress against change and then trying to adapt to it, then the twenty-first century is about embracing change, not fighting it ... traditional approaches to learning are no longer capable of coping with a constantly changing world". Embracing change has the inherent implication that in some instances failure is inevitable in uncertain environments and learning from this failure, through fail safe experimentation could serve as a means for exploring intentional interventions directed at stimulating and disrupting emergent patterns in complex space.

McGrath (2011:78) would appear to concur with this sentiment in declaring that if organisations were to adopt what is termed to be intelligent failure they would become more agile, and better at risk taking more adept at organisational learning. Mauboussin (2011:92) shares the view that small experiments with controls serve as an ideal means for embracing complexity. Edmondson (2008:63) in fact cautions that if employees feel that they can't speak about small failures the organisation is at risk of even larger failure. Learning from experimentation and possible failure would appear to constitute a means for dealing with emergent complexity.

4. CONCLUSION

The linkage between contextual complexity and the need for a culture of learning surfaces as a pertinent finding, stemming from the literature research. Rosenhead (1998:1), for instance, concludes that the need for an emphasis on learning in effect has its genesis in the fact that the future is in principle unknowable for systems of any complexity. Of equal relevance is the finding that nurturing a culture of learning in itself constitutes a complex process. As noted by Roux et al. (2009:14), "culture is neither managed nor controlled" it is in fact an emergent phenomenon. The use of ordered space management practice in dealing both with complex business environments and the nurturing of a culture of learning, as may be determined from the preceding discourse, will leave management frustrated.

Inferred from the discussion are that Snowden and Boone's (2007:75) tools for managing in a complex domain may be more effective. Suggested therefore, is the need for a future more detailed analysis of these tools and their application in practice.

In a world of unprecedented emergent change, that certainly has an immense impact on communities and institutions, the need for nurturing a culture of learning could never be greater. The failure to effectively deal with culture transformation, could be more effectively dealt with if a complex domain perspective of the problem is adopted.

Managers of contemporary institutions are increasingly confronted with the management challenges associated with both ordered and complex states. The Cynefin Framework, it is suggested, assists them in determining both the prevailing operative contexts and the most appropriate management response, particularly in terms of the nurturing of a culture of learning. An important additional finding from the literature analysis is the fact that it is virtually impossible for individual managers to gain a holistic view of the vast array of cause and effect relationships that give rise to emergent outcomes. Managers who attempt to impose order within complex contexts will fail. This necessitates a need for experimentation and trial and error learning in order to find innovative solutions for dealing with the complex conditions that exist.

The best suggested means to achieve this is to establish context of open discussion, where dissent and diversity of views and opinions expressed by staff members enrich the search for appropriate responses for dealing with the issues concerned. It is a context where small experiments could well lead to failure, yet the learning that emanates from such failure, plays a fundamental role in discovering new innovative solutions. As noted by Edmondson (2011:49) it means management need to jettison stereotypical notions of success and embrace the lessons learnt from failure.

In the final instance the literature analysis seems to provide an answer for the question posed by Thomas and Brown (2011:17), as to what happens to learning when institutions move from stable infrastructures of the twentieth century to the fluid infrastructures of the 21st century. Learning becomes pervasive, complex and a never-ending quest of finding answers for intractable problems presented by Black Swan events. It necessitates the need for a culture of learning that can best be nurtured by means of a complex systems approach, which is shaped by management's active participation in the day-to-day interaction and negotiation processes that take place within the institution.

REFERENCES

AXELROD R & COHEN MD. 1999. Harnessing complexity: organizational implications of a scientific frontier. London: Free Press. [ Links ]

BOULTON J. Undated. Managing in an age of complexity. [http://www.embracingcomplexity.co.uk/Admin/uploadFiles/ManaginginanAgeofComplexity.pdf; downloaded on 2011-7-5. [ Links ]]

BROWAEYS MJ & BAETS W. 2003. Cultural complexity: a new epistemological perspective. The Learning Organization, 10(6):332-339. [ Links ]

CILLIERS P. 1998. Complexity and postmodernism: Understanding complex systems. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

COUTU DL. 2002. The anxiety of learning. Harvard Business Review, 80(3):100-106. [ Links ]

DIMITROV V. 2003. Paradigm of complexity: The law of emergence. [http://www.zulenet.com/vladimirdimitrov/pages/paradigm.html; downloaded on 2001-9-4]. [ Links ]

EDMONDSON AC. 2008. The competitive imperative of learning. Harvard Business Review, 86(7/8):60-67. [ Links ]

EDMONDSON AC. 2011.Strategies for learning from failure. Harvard Business review, 89(4):48-55. [ Links ]

FRIEDMAN TL. 2006. The world is flat: The globalized world in the twenty-first century. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

GARVIN DA, EDMONDSON AC & GINO F. 2008. Is yours a learning organization? Harvard Business Review, 86(3)109-116. [ Links ]

GOVENDER V. 2009. Promoting a culture of learning and institutionalising a learning organisation in the South African public sector. Journal of Public Administration, 44(2):364-379. [ Links ]

HAGEL J & BROWN JS. 2009. The big shift: measuring the forces of change. Harvard Business Review, 87(7/8):86-89. [ Links ]

KIECHEL W. 2010. The lords of strategy: The secret intellectual history of the new corporate world. Boston: Harvard. [ Links ]

KURTZ CF & SNOWDEN DJ. 2003. The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world. IBM systems journal, 42(3):462-483. [ Links ]

MALHERBE D, SCANELL J & VAN DER MERWE B. 2011. Learning about technology for teams in complex development environment. Paper presented at the ISEM, September, 2011 conference, Stellenbosch, Western Cape, South Africa. [ Links ]

MAUBOUSSIN MJ. 2011. Embracing complexity. Harvard Business Review, 89(9/10):89-92. [ Links ]

MBEKI TM. 1997. The need for a culture of learning and teaching. [http://www.search.gov.za/info/previewDocument.jsp?dk=%2Fdata%2Fstatic%2Finfo%2Fspeeches%2F1997%2F990623227p2002.htm%40Gov&q=(+((mbeki)%3CIN%3ETitle)+)%3CAND%3E(category%3Ccontains%3Es)&t=MBEKI%3A+LAUNCH+OF+THE+CULTURE+OF+LEA RNING+AND+TEACHING+CAMPAIGN; downloaded on 2010-5-20]. [ Links ]

McGRATH RG. 2011. Failing by design. Harvard Business Review, 89(4):76-83. [ Links ]

PETERS T. 2003. Re-imagine! Business excellence in a disruptive age. London: DK. [ Links ]

REBELO TM & GOMES AD. 2010. Conditioning bfactors of an organizational learning culture. Journal of workplace learning, 23(3):173-194. [ Links ]

ROSENHEAD JR. 1998. Complexity theory and management practice. [http://human-nature.com/science-as-culture/rosenhead.html; downloaded on 20117-14]. [ Links ]

ROUX DJ, MURRAY K & VAN WYK E. 2009. Enabling effective learning in catchment management agencies: A philosophy and strategy. Report submitted to the Water Research Commission (WRC) and the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. WRC Report, TT421/09 November 2009. [ Links ]

SARGUT G & MCGRATH RG. 2011. Learning to live with complexity: How to make sense of the unpredictable and the undefinable in today's hyperconnected business world. Harvard Business Review, 89(9):68-76. [ Links ]

SANZ-VALLE R, NARANJO-VALENCIA, JIMÉNEZ-JIMÉNEZ D & PEREZ-CABALLERO L. 2011. Linking organizational learning with technical innovation and organizational culture. Journal of knowledge management, 15(6):1-24). [ Links ]

SCHNEIDER B, GUNNARSON SK & NILES-JOLLY K. 1994. Creating the climate and culture of success. Organizational Dynamics, 23(1):17-29. [ Links ]

SEDIBE, M. 2006. A compare study of the variables contributing towards the establishment of a learning culture in schools. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

SEEL R. 2000. Culture and complexity: new insights on organisational change. Organisations & People, 7(2):2-9. [ Links ]

SNOWDEN DJ & BOONE ME. 2007. A leader's framework for decision making: Wise executives tailor their approach to fit the complexity of the circumstances they face. Harvard Business Review, 85(11):69-76. [ Links ]

TALEB NN. 2007. The Black Swan: The impact of the highly improbable. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

THOMAS D & BROWN JS. 2011. A new culture of learning: cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change. London: Soulellis. [ Links ]

TOSTI DT. 2007. Aligning the strategy and culture for success. Performance improvement, 46(1):21-25. [ Links ]

VAN RENSBURG A. 2011. Complexity management: A crystal ball for executives. Paper presented at the ISEM, September, 2011 conference, Stellenbosch, Western Cape, South Africa. [ Links ]