Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.8 no.1 Meyerton 2011

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Retailing in disadvantaged communities: the outshopping phenomenon revisited

JW Strydom

Department of Business Management, University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the outshopping trend that is evident in the black township areas of South Africa. Previous research ascribed this trend mainly to the lack of planned retail infrastructure in these areas. In view of the massive retail investment that occurred, it was decided to revisit the reasons for this phenomenon.

In the ensuing follow-up study, both exploratory and descriptive research was used to confirm that the previous study had been correct in maintaining that sufficient retail infrastructure should counteract the outshopping problem. What is surprising, however, is that outshopping still occurs among the higher income level consumers and that it is especially the pricier high-ticket items that are bought outside Soweto, the township on which the research focused. The negative impact of outshopping on the continued existence of retailers stocking similar items inside the township is mentioned. The repercussions of the opening of the new retailing infrastructure on the existing retailers are also investigated. It is concluded that outshopping is an international phenomenon that will always occur and that retail management in townships should take note of the impact of outshopping on the store variety in these centres.

Key phrases: outshopping, black townships, disadvantaged consumers, retailing facilities, Soweto

1 INTRODUCTION

The general dealer where you could buy on credit forms part of the folklore of South African retailing. With the advent of improved infrastructural development and generally better-informed consumers, the nature and range of retail facilities have changed. Today, consumers have a wide range of retailing facilities available and are supported by retailers ranging from near to home to regional shopping centres some distance from their homes. Increasingly, some consumers travel further to these outlying trade areas to buy goods and services, spending a substantial part of their income outside the local community. These specific consumers are described as outshoppers (Choe, Pitman & Colins 1997:1; Dunne & Lusch 2008:104; Engel, Blackwell & Miniard 1993; Paddison & Calderwood 2007:138).

Outshopping, which occurs in various countries of the world, is especially prevalent in rural and disadvantaged areas where fewer retailing options exist, and where retailers that have been serving the local community for years are closing down. This is called the "triple jeopardy phenomenon" where small rural retailers have fewer customers, who buy less often and spend less per shopping trip (Kim & Stoel 2010:70). Some of the major retailing groups have developed smaller versions of their hypermarkets and supermarkets to cater for customers in larger towns, attracting some of the clientele of the surrounding small towns. This further leads to the demise of these retailers.

These kinds of outshopping problems are familiar to South Africa where rural towns are suffering due to the lack of retailing infrastructure. However, additional reasons for outshopping exist in South Africa, and these are especially relevant to the black townships. Such reasons include the lack of alternative retail institutions, which coupled with limited merchandise selection, poor service and high prices, compelled the customer to travel further distances to larger towns and cities to shop for products and services. In South Africa, outshopping therefore initially came about for the same reasons as in other countries, but there were also different causal factors.

South African retailers had their own unique problems due to the structural problems inherited from the previous socio-political system. One of the consequences of apartheid was the establishment of separate black residential areas in South Africa, of which Soweto is one, and the restriction of business development in these areas (Butler 1989:50). As a result of this historical disadvantage, township retailers struggled to survive and consumers were under-serviced with only rudimentary retail services being provided (Strydom, Martins, Potgieter & Geel 2002:18). Klemz, Boshoff and Mazibuko (2006:591) call this phenomenon in the townships a "dual economy" situation and Dunne and Lusch (2008:225) refer to it as being "understored"; a situation where too few stores are available to meet the needs of the customer.

The fall-out of this socio-political system created, inter alia, disadvantaged township communities with the barest of retailing infrastructure as was evident from research in the black township of Soshanguve (Strydom et al. 2002:18) and other townships such as Soweto. The findings of the research by Strydom et al. (2002:18-23) showed that the South African shopping environment was split between a modern first-world shopping infrastructure controlled by traditionally white business-owned retailing facilities, and emerging third-world shopping retailing facilities hampered by poor infrastructure in black townships under black ownership.

The majority of formal retailers in these townships were clustered in small, formal neighbourhood centres. Most of the shops were classified as general retailers but there were also a growing number of informal retailers competing with informal retailing structures. These structures included spaza shops (convenience retailers operating from a room in a house), hawkers (selling mostly perishable products) and shebeens (selling beer and other forms of liquor). In most of the black townships, businesses were scattered throughout the residential areas. It was only after 1994 that the new government compelled the retailing infrastructure in the townships to be properly planned and developed.

This led to the opening of various new retailing facilities such as shopping centres and regional shopping malls. In their previous study, Strydom et al. (2002:18-23) identified the lack of planned retail development in these black townships as the main reason for outshopping. In view of the retail infrastructure investment that occurred in the period after 1994, it was decided to revisit the premise of the findings of the 2002 results.

2 PROBLEM STATEMENT

Since the advent of a democratic government in 1994, major retailing investments occurred in the black townships leading to a rapid increase in the number and size of formal shopping centres in these areas. McGaffin (2010:1) reported that since 1962 a total of 160 shopping centres were developed in South Africa, with about 1.7 million square metres of retail floor space added of which 53% was developed since 2000. Most of these recent developments were in the township areas. With this massive increase in modern shopping centres in these areas the question arises whether this hefty investment in retailing infrastructure would prevent the haemorrhaging of disposable income of consumers and impede the incidence of outshopping.

3 OBJECTIVES OF THE ARTICLE

As stated in the introduction the objectives of the study are:

• To determine if the outshopping phenomenon still occurs in the South African townships.

• To ascertain if the South African reasons for outshopping are the same as for other countries of the world.

• To determine what type of goods and services are bought inside and outside the townships.

• To determine the expenditure patterns of Sowetan residents per income group between different business type outlets.

The article is structured as follows: first, outshopping as it developed in black South African townships is described and reasons are provided for its occurrence. The prevalence of outshopping in other countries is discussed next and the results of an empirical study on outshopping that was done in the township community of Soweto in 2007 are reported. The article concludes with a discussion of the theoretical and managerial implications of the findings and suggestions for further research in this field.

4 OUTSHOPPING IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN TOWNSHIPS

Two studies (Nel 1982:1-76; Van Zyl & Ligthelm 1998:1-80) researched the problems regarding retailing infrastructure of township consumers. General problems that were identified include the following (Nel 1982:12-13; Van Zyl & Ligthelm 1998:34-35):

• Lack of self-service: For most of their purchases, black consumers preferred self-service outlets where they could have the opportunity to select the product themselves and compare prices. In most cases, local township retailers during the time of the study used counter service to sell to the consumer.

• High prices: Consumers felt that they were being exploited by local retailers, who charged high prices for products and services.

• Poor quality: There was the perception among township residents that they were paying high prices for stale and substandard goods.

• Lack of variety: The variety of goods available in township businesses were severely limited, according to the respondents interviewed at that stage.

It is evident that the previously mentioned socio-political interventions inhibited the retailer development in these areas and caused considerable outshopping from the black townships to the regional shopping malls and central city shopping areas. In a study conducted in 1999, it was found that middle- and upper-class blacks, of which 75% still lived in the traditionally black townships at that time, spent 93.4% of their total household budget at formal outlets and only 6.6% at informal outlets. Most of these formal outlets at that stage were outside the townships. Expenditure at informal outlets occurred inside the townships through spaza shops and shebeens (Martins 2000:35-37).

After the change in the political dispensation in 1994, the call went out to rectify this retail infrastructure backlog and to address the needs of residents in these disadvantaged areas. The economic strategy that was adapted by the new government was to increase black disposable income and black participation in the mainstream South African economy. The development of shopping infrastructure, preferably by black-owned businesses in the townships, was encouraged. One of the last areas in South Africa that was earmarked for retail development were in the townships in places such as Mafikeng, Umlazi, Mitchells Plain and especially in the Gauteng area in townships such as Tembisa, Lenasia, Jabulani, Soshanguve, Atteridgeville, Alexandra and Soweto.

With the influx of new shopping malls, consumer buyer behaviour also changed. Townships centres now became destinations of choice. Thys (2009:7) reported that in Pretoria the new township shopping centres attracted 56.25% of the local population's spending power, whilst the figure in Johannesburg was 52.17%. The same trend was evident in Durban where 52.17% of the residents bought from retailers in the township. Only in Cape Town did the township population buy less than half of their purchases from township retailers (41.67%). This is ascribed to the fact that there are fewer township centres located in the Cape Town townships. Thys (2009:7) also reported that it is primarily the Living Standards Measure (LSM) groupings of 4 to 7 that are supporting these township retailers and that convenience is the major reason for shopping from these retailers.

Since 1994, the public sector investment in Soweto amounted to more than R500 million, which was used to provide the necessary infrastructure, opening the way for private investors to invest more than R3 billion in various projects such as transportation services, a hotel, and shopping centres. Not all of the shopping centres are successful (Kloppers 2009:10). The Maponya Mall regional centre, which opened in 2007, is struggling. This was ascribed to the wrong tenant mix and not enough customers in the higher LSM groupings (8 to 10) living in its catchment area. On the other hand, the Jabulani Centre is performing better because the product range presented by its retailers fits the needs of the customers. Customers living in the Jabulani catchment area are categorised into the following segment categories: LSMs 8 to 9 (22%), LSMs 5 to 7 (62.5%) and LSMs 2 to 4 (15%).

Having looked at outshopping in the South African townships, it is necessary to compare this with the occurrence of outshopping in other countries to ascertain if the reasons for South African outshopping were similar to those found in other countries where outshopping occurs.

5 OUTSHOPPING IN OTHER COUNTRIES

Most of the problems encountered by South African retailers in the past are not unique to South Africa, but generic to retailers in developing and some developed countries. Samiee (1990:34) summarises the problems that retailers encounter in developing markets as follows:

• The lower income levels of residents result in less disposable income for the customer, limiting the opportunities for development of retailing infrastructure in the area where they live.

• Limited car ownership of residents confines the shopping mobility of the customer. This limits consumers to buying in the geographical area in which they reside.

• The lack of public transportation also impacts negatively on the mobility and shopping options of customers.

• The lack of electricity and refrigeration forces customers to buy products on a daily basis and limits them from buying in bulk and obtaining the resultant economy-of-scale savings.

• The inadequate storage space, which is due to the limited living space, prevents customers from buying in bulk. This increases the price they pay for products.

Rivero and Vergara (2008:65-66) reported on research done in Chile, an emerging country. They investigated how the entry of large retailers, such as a hypermarket and department stores, impacted on local retailers in disadvantaged areas. Their findings are that employment opportunities are created when these new large retailers enter the market. There is also a knock-on effect in that upmarket supply chain members, such as suppliers, follow the new retailers, thus creating a halo-effect of added business activities to these areas. There is however also consensus that local retailers exit or contract in size and turnover after the entry of these larger retailers.

D'Andrea, Lopez-Alleman and Stengel (2006:661-673) reported on a study that was done in various countries in Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica and Mexico). In this study it was ascertained that whilst disadvantaged customers favour the large retailers, their needs could also quite effectively be served by local small retailers. The net effect of the dominance of the large retailers in these countries is to limit the availability of small retailers to the disadvantaged customer, resulting in longer distances to be travelled, more time and money spent on transportation, and customer dissatisfaction with the lack of personal relationships and emotional proximity with personnel of these large retailers.

It is however not only in developing countries that the problem of outshopping occurs, as it is also found in developed countries such as Scotland. In a study done in the city of Glasgow in the west of Scotland, a severely disadvantaged neighbourhood (Greater Pollok) was researched. In this neighbourhood more than 60% of the households had no cars and male unemployment at the time of the research was running at 30%. Residents of this neighbourhood were dependent on buying staple items such as bread, fruit, milk and vegetables from local convenience shops, usually at a much higher price (Ellaway & Macintyre 2000:53-54).

Lee, Johnson and Gahring (2008:145) reported on research done in the United States of America (USA) where the impact of the opening of discount retailers, such as Wal-Mart, on the local retailing infrastructure in smaller towns was profound. The results showed that local retailers were struggling to compete on price and product availability. The store patronage behaviour of the customers also favoured the new retailing formats because the existing small retailers did not meet the local consumers' expectations regarding merchandise assortment and product availability.

In Aura, in the south-west of Finland, the retailers in the town, which is only 30 km from the much larger city of Turku, have to compete with two out-of-town shopping centres. The popularity of these shopping centres, to the detriment of retailing activities in Aura, is ascribed to outshopping. The results of the study indicated that customers in Finland supported the closest shopping centre that fulfilled their needs, that cars were used predominantly and that the outshopping problem could be countered when a good variety of local retailing stores were available (Marjanen 2000:196-198).

Virchez and Cachon (2004:51) reported that in a certain area in Canada, only one new part-time employment opportunity was created by the new shopping centres, but that about one-and-a-half full-time employment opportunities were lost as a result of the closure of existing retail stores.

In England, rural towns also reported a closure of food retailers and according to Paddison and Calderwood (2007:138) 75 % of all English rural settlements lacked both a general store and a village shop. This compelled the English rural population to drive further to surrounding larger towns to buy groceries. Incidences of European outshopping have several implications, as stated by Paddison and Calderwood (2007:138-139):

• The multiplier effect when retailing infrastructure in a small town breaks down, has a knock-on effect that negatively influences the economic eco-system in total, resulting in overall job losses for the community.

• Once outshopping commences, it turns into a self-fulfilling prophecy as the trend towards outshopping gathers momentum and less shopping opportunities become available in town.

• The occurrence of outshopping is a factor of the peripheral distance to the larger shopping centres. The nearer the proximity of the shopping alternative, the more vulnerable the local retail institutions and the greater the chances of closure.

• Outshopping is also closely associated with the higher income segments of the population. These consumers have enough disposable income to make a considered contribution to the continued existence of the existing retail infrastructure.

To summarise: only limited empirical research on the effects of the large food retailers on the existing retailing infrastructure in previously disadvantaged communities such as South Africa is available. In the few studies that were fairly similar, the golden thread is the decline and closure of these small retailers and the resultant job losses that were reported in the disadvantaged areas. Having set the scene on how outshopping is experienced in South Africa and other parts of the world it is now necessary to investigate the aftermath of the introduction of new retailing infrastructure and its effect on outshopping in Soweto.

6 RESEARCH DESIGN

Due to the fluid nature of the developments in the South African townships, both exploratory and descriptive research designs were incorporated in this research. As a result of the lack of previous in-depth research in this township, it was decided that exploratory research should first be conducted into the Soweto retail infrastructure.

The target population was Soweto because it is one of the biggest under-stored townships in South Africa, with a population of more than one million people. This process involved, firstly, an exploration of the size of the Soweto consumer market, focusing primarily on the number of people residing in Soweto. This process was further complemented by gaining a spatial orientation of retail shopping malls/centres located within the demarcated geographic boundaries of Soweto. For this purpose, personal site visits were undertaken. A disproportionate stratified sample design was then used. The final sample consisted of 690 respondents spread over 11 subareas of Soweto (Tustin 2008:1-50).

The research was descriptive and quantitative in nature as it involved observing and describing the shopping behaviour without influencing it in any way and questionnaires were utilised to determine shopping patterns of Soweto residents. Content validity has been established in the original study (Tustin 2008:1-50). The hypotheses tested are based on reported income and expenditure levels of the respondents. No summated construct scale was used and no reliability test thus applies.

7 RESULTS FROM THE SOWETO SURVEY

The corpographic results of the survey are presented below.

7.1 YEARS OF RESIDENCE IN SOWETO

The average years of residence in Soweto per subarea differed based on the age of the area in which the respondents lived. In the various subareas, the average years of residence ranged from the longest in subarea H (Chiawelo Ext. 2, 3, 4, 5, Mapetla, Phiri, Senaoane, Dlamini, Kliptown) where the average was 32 years, to subarea K (Bram Fischerville Ext. 1, Slovoville, Slovoville Ext. 1, Doornkop new extensions, Thulani and Tsepisong), where the average was the shortest, namely 8 years.

The overall average of years of residence was 23 years. This was sufficient to elicit reliable responses regarding the introduction of the new shopping malls and how it impacted on their personal shopping patterns. Thus, the respondents would be able to answer questions regarding the before and after situation, and the impact of these modern shopping centres on the occurrence of outshopping.

7.2 EMPLOYMENT STATUS OF RESIDENTS

Respondents were asked about the employment status of household members to help ascertain their disposable income. The average number of members unemployed was 2.6 whilst 0.42 were employed inside Soweto and 1.24 worked outside Soweto. The average total number of household members employed was 1.66 out of an average total number of employable household members of 4.50. As this study was done in 2007 during a period of strong economic growth, the average employment numbers could be much lower in the current period of economic downturn.

7.3 MONTHLY DISPOSABLE INCOME

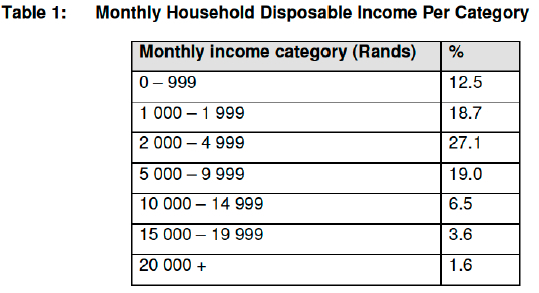

Monthly disposable income is calculated as total household income less tax paid. It must be acknowledged that respondents tend to underreport on their real monthly income when interviewed by outsiders. The monthly disposable income categories are reflected in Table 1.

It is shown that 31.2% of the households have a monthly income of below R2 000 per month and that 27.1% have an average monthly income of between R2 000 and R4 999. The first three categories were combined and classified as the low-income group. The middle income group was classified as those respondents with a disposable income of between R5 000 and R14 999. Table 1 shows that 25.5% of the population form part of the middle-income group. The high income group was described as those with an average monthly income of R15 000 plus, making up 5.2% of the interviewed population.

7.4 HOUSEHOLD CONSUMER PURCHASES BY TYPE OF BUSINESS OUTLET

There are various business outlets where the Sowetan households could spend their disposable income. For the purposes of the study the business outlets were divided into six categories as described below:

Outside Soweto refers to all the retail outlets situated outside the borders of Soweto. These businesses attracted Sowetan customers and can be classified as retailers where outshopping occurs.

New and established retail malls and centres inside Soweto are the Dobsonville Shopping Centre (1994), the Protea Garden Mall (2005), the Baramall Shopping Centre (2006), the Jabulani Shopping Complex (2006) and the Maponya Mall/Centre (2007).

The established (old) shopping malls inside Soweto that opened more than 30 years ago, include Black Chain (1980s) and Crossroads (1980s).

The industrial areas inside Soweto include businesses situated in the industrial areas where manufactured products can be bought directly from the manufacturer.

Home-based businesses inside Soweto: the most well-known examples are the spaza shops, tuck shops, shebeens and taverns.

Street vendors/hawkers/street-front shops inside Soweto operate as stand-alone business outlets aimed at convenience shopping.

The household purchases per business outlet type are presented in Table 2.

It is clear from Table 2 that outshopping (18.8%) still occurs despite the introduction of the new shopping malls. This can be partly ascribed to the fact that the majority of members of households work outside Soweto and buy consumer goods near their place of work. Further reasons provided include shoppertainment, the wide range of products and pricing of these stores.

It is also clear that the new and established malls are getting a major share of the custom of Soweto residents (43.4%). The main reasons for this trend include convenience, shopper-tainment and low pricing. What is also of interest is that the home-based shop that is the spaza shops, are also getting a significant 10.4% share of the market. This is mostly due to the convenience provided by these businesses.

This finding was corroborated by the respondents who mentioned accessibility and convenience as the main reasons. It is also interesting to note that similar reasons were provided for outshopping as for shopping at the new/established malls and centres inside Soweto. It can be deduced that when new shopping facilities are on par with the outside shopping facilities it could counteract the outshopping that occurred in the past. It was the most recently opened shopping malls, namely the Maponya Mall and Jabulani Shopping Centre that attracted most of the respondents. This could be ascribed to the novelty factor of these new shopping malls that opened just at the time when this research was done. Regarding the respondents' outshopping activities, the most popular shopping malls that were visited outside of Soweto were: Sandton City Shopping Centre, Nelson Mandela Square at Sandton City, Southgate Mall in Mondeor, Westgate Shopping Centre in Roodepoort and Northgate Shopping Centre in Randburg.

In the process of focusing on the major differences regarding shopping inside versus outside Soweto, the business outlet types as depicted in Table 2 were grouped together into three broad categories: the retailers outside Soweto, the newly established Soweto retailing malls and centres, other Soweto businesses, which include the categories of old shopping malls, industrial areas, home-based retailers and street vendors/hawkers/street-front shops.

7.5 SIZE OF THE SHOPPING BASKET

Respondents were questioned regarding the size of their purchases per shopping trip to different shopping outlets in Soweto. The responses were categorised into the following three categories: trolley shopper, basket shopper and virtual shopper. A trolley shopper is a bulk shopper that purchases his/her groceries per trolley in a weekly or monthly fashion. A basket shopper, also called a top-up shopper, buys for convenience, making smaller purchases on a more regular basis, whilst a virtual shopper buys products online. The shopping profile per business outlet per category is depicted in Table 3.

The majority of households do their bulk shopping either at the shopping malls inside Soweto or outside of Soweto. Basket shopping or convenience shopping is mostly done inside Soweto at other types of retailers.

7.6 CHANGES IN CONSUMER PURCHASE PATTERNS DUE TO MALL DEVELOPMENTS

The respondents were also asked how their consumer spending patterns had changed since the introduction of the new shopping centres. There was consensus that more goods and services were bought inside Soweto than outside Soweto, thus reversing the previous situation of outshopping. The results are depicted in Table 4.

The most obvious beneficiaries of the new developments were the shopping malls that had been erected since 1994. It is also of interest that other business formats also benefited from the development of the shopping malls, but to a lesser extent.

However, this figure is deceptive in that the growth in the middle class, with increased disposable income, also occurred in the same period. This deduction is corroborated by the responses from the respondents that indicated that they spend less of their disposable income at the other (old) shopping outlets. The net beneficiaries were therefore the shopping malls erected since 1994, which benefited on average R1 285.00 per household on an estimated R4.8 billion turnover for Soweto for the 2007 financial year. The sales of fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) and especially the grocery, toiletry and confectionery products (GTC) increased the most. On the other hand, the slowest increases in sales per category were in the furniture, radio and musical instruments, entertainment, linen and soft goods and electrical equipment products, most of which are still bought outside Soweto. Regarding the issue of outshopping, it was calculated that in 2007 about 37.5% of the monthly disposable income in Soweto was spent outside Soweto, whilst 46.5% was spent inside the area at the new/established shopping malls with the remaining 16% spent at the other formats of business inside Soweto.

It is clear that there is a general trend towards buying inside Soweto. It is especially the high-income group that are staunch supporters of the new shopping malls and centres in Soweto. It is also interesting that the proportional spend of the residents outside Soweto is quite low (18.8%) but the percentage of monthly disposable income spent outside Soweto is disproportionately high, as can be seen in Table 5.

The breakdown of the average monthly expenditure into the three income categories of low-income group, middle-income group and high-income group (previously explained) was divided between the three shopping options (see Figure 1), namely shopping outside Soweto, shopping at the new and existing shopping centres and malls inside the township and shopping at the other Soweto businesses (also called businesses in Soweto outside the malls).

Based on the above, it was decided to perform some inferential testing whilst setting the research hypotheses, which are discussed below.

7.7 RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

7.7.1 Research Hypothesis 1

The first hypothesis focused on the three defined income groups and their support for the three defined categories of retailers as mentioned in Table 6 above. The null and alternative hypotheses were therefore formulated as follows:

Ho[1] The three income groups do not differ significantly regarding their support for retail outlets outside Soweto (outshopping) Ho[1a], inside Soweto in the new and existing shopping malls and centres Ho[1b] and for the rest of the businesses inside Soweto Ho[1c].

The alternative hypothesis with its three sub-hypotheses was formulated as follows:

H1[1] The three income groups differ significantly regarding their support for retail outlets outside Soweto H1[1a], inside Soweto in the new and existing shopping malls and centres H1[1b] and for the rest of the businesses inside Soweto H1[1c].

Testing of these hypotheses

One-way ANOVA was used to determine if the means of the three groups differ significantly with regard to the type of outlets used: that is, outshopping, shopping at the new and existing malls and centres inside Soweto and the other businesses outside the malls and centres, but inside Soweto. One-way ANOVA is a statistical technique used to compare means of two or more samples (using the F- distribution). This technique can be used only for numerical data. The ANOVA tests the null hypothesis that samples in two or more groups are drawn from the same population. As can be seen from Table 6 all three sub-hypotheses are rejected. A significance level of 5% (a = 0.05) was used.

The three alternative hypotheses are accepted, thus:

H1[1] The three income groups differ significantly regarding their support for retail outlets outside Soweto H1[1a], inside Soweto in the new and existing shopping malls and centres H1[1b] and for the rest of the businesses inside Soweto H1[1c].

This deduction can be summarised in Figure 2, which puts the differences between the three income groups in perspective.

Figure 2 depicts the average monthly expenditure per type of shopping outlet and shows the steep growth of support from the high-income group for the shopping malls and centres inside Soweto. It also indicates the small change in support between the three types of outlets for the low-income grouping.

7.7.2 Research Hypothesis 2

The second research hypothesis was formulated to ascertain if there was a significant shift in the disposable expenditure of shops outside Soweto, at the mall and centres inside Soweto and the remaining Sowetan retailers. The null hypothesis was therefore developed to include two sub-hypotheses:

Ho[2a] There is no significant difference between the expenditure by customers outside Soweto and in the shopping malls and centres of Soweto.

Ho[2b) There is no significant difference between the expenditure by Sowetans inside the Sowetan malls and centres and the other businesses inside the Sowetan area.

The alternative two sub-hypotheses that were developed were therefore:

H/[2a] There is a significant difference between the expenditure by customers outside Soweto and in the shopping malls and centres of Soweto.

H/[2b] There is a significant difference between the expenditure by Sowetans inside the Sowetan malls and centres and the other businesses outside in the Sowetan area.

Testing of these hypotheses

A paired sampled t-test, which is a parametric test testing for statistical significant differences in means between groups of paired observations, was used at the 5% level of significance (a = 0.05). The results are presented in Table 7.

8 CONCLUSION

The focus of the article was the outshopping trends occurring in Soweto and cannot be generalised for the rest of South Africa. Soweto is however one of the largest townships in South Africa which provides a good indication of the current trends regarding outshopping in the South African townships. The results of the survey indicate that there was a major shift in consumer spending back to Soweto with the introduction of new retailing facilities. This was especially the case for normal grocery products such as FMCG and the GTC products. This confirms the findings of the previous study by Strydom et al. (2002) regarding the lack of retailing facilities being the major reason for outshopping in the black townships.

What is of interest is that outshopping per se has not completely stopped, notwithstanding the introduction of the modern new retailing infrastructure in Soweto. This finding is in line with the results on outshopping in other countries. These results confirm that modern retailing facilities will always motivate people to visit, thus resulting in generic prevalence of outshopping. This is something that investors, store developers and centre managers must consider in the development and composition of the optimum store-mix per shopping centre in the South African townships.

It was also shown that the percentage of monthly disposable income spent outside Soweto was disproportionately high, implying that some big-ticket items like furniture and high technology products were still being bought outside Soweto. The occurrence of this type of outshopping needs to be further investigated as these products are available in the retailing facilities of Soweto and the outflow of disposable income is definitely impacting on the future viability of selling such items in these retailing facilities. Furthermore, the older retailing facilities inside Soweto are also under duress as they compete with the modern retailing facilities. These retailers have existed for a number of years and are in most cases the sole livelihood of the owners and a source of income for their employees. The slowdown in growth and the stagnation that these retailers are experiencing further confirm what was reported in other countries, namely that the older retailers fell by the wayside due to the opening of new retailing facilities.

In the final instance, it would seem that, despite the most modern retailing facilities available in the townships, there will always be a need for outshopping in South Africa. Various reasons exist for this, such as that residents work outside the black townships and buy products near their place of work, more competitive pricing from retailers in other parts of the city, and shoppertainment, where people want to visit new retailing facilities and enjoy the ambience and social interaction with other communities in other parts of cities and towns. The general dealer of the past, who sold his wares on credit, is now part of South African folklore. The same could be happening in the townships where older types of retailers are struggling and outshopping is still taking disposable income out of the area. In this sense what is happening domestically is corroborated with the outshopping trends in foreign countries such as the Latin American countries, Denmark, Canada, the USA and the United Kingdom.

Only time will tell if South African retail managers have taken note of what was happening in foreign countries and is now happening in the South African townships.

These developments create the opportunity for further research in the South African retailing environment especially with regard to the reasons why high-value items are not bought inside the township centres.

REFERENCES

BUTLER, C. 1989. The extent and nature of black business development. LS Associates, Sandton. [ Links ]

CHOE, ST., PITMAN, GA. & COLINS, FD. 1997. Proactive retail strategies based on consumer attitudes towards the community. International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 25(11):365-371. [ Links ]

D'ANDREA, G., LOPEZ-ALLEMAN, B. & STENGEL, A. 2006. Why small retailers endure in Latin America. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 34(9):661-673. [ Links ]

DUNNE, PM. & LUSCH, RF. 2008. Retailing (6th edition). Mason: OH, Thomson Southwestern. [ Links ]

ELLAWAY, A. & MACINTYRE, S. 2000. Shopping for food in socially contrasting localities. British Food Journal, 102(1):52-59. [ Links ]

ENGEL, JF., BLACKWELL, RD. & MINIARD, PW. 1993. Consumer behaviour (7th edition). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. [ Links ]

KIM, J. & STOEL, L. 2010. Factors contributing to rural consumers' inshopping behavior: Effects of institutional environment and social capital. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(1):70-87. [ Links ]

KLEMZ, BR., BOSHOFF, C. & MAZIBUKO, NE. 2006. Emerging markets in black South African townships. European Journal of Marketing, 40(5/6):590-610. [ Links ]

KLOPPERS, E. 2009. Soweto is meer as net 'n township. Sake Rapport, 13 September:10. [ Links ]

LEE, J., JOHNSON, KKP. & GAHRING, SA. 2008. Small-town consumers' disconfirmation of expectations and satisfaction with local independent retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 36(2): 143-157. [ Links ]

MARJANEN, H. 2000. Retailing in rural Finland and the challenge of nearby cities. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 28(4/5):194-206. [ Links ]

MARTINS, JH. 2000. Income and expenditure by product and type of outlet of middle and upper class Black households in Gauteng, 1999, Research Report 275, Bureau of Market Research, Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

McGAFFIN. R. 2010. Shopping centres in townships areas: Blessing or curse? [Internet:www.urbanlandmark.org.za/newsletter/issue/0501/download/shopping_centres_in%20_township_areas.pdf; downloaded on 2011-02-08. [ Links ]]

NEL, PA.1982. Opportunity knocks for black businessmen, African Business, July: 12-13. [ Links ]

PADDISON, A. & CALDERWOOD, E. 2007. Rural retailing: a sector in decline. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 35(2).136-155. [ Links ]

RIVERO, R. & VERGARA, R. 2008. Do large retailers affect employment? Evidence from an emerging economy. Applied Economics Letters no.15. [ Links ]

SAMIEE, S. 1990 Impediments to progress in retailing in developing nations in Findlay, AM, Paddison, R & Dawson, JA. 1990. Retailing environment in developing countries. London: Routledge. 30-42 [ Links ]

STRYDOM, JW., MARTINS, JH., POTGIETER, M. & GEEL, M. 2002. The retailing needs of a disadvantaged community in South Africa. South African Business Review, 6(1). [ Links ]

TUSTIN, D. 2008. The impact of Soweto shopping mall developments on consumer purchasing behaviour, 2007. Research Report 372, Bureau of Market Research, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

THYS, L. 2009. Swart diamante laat township-sentra blink. Nuusfokus, Rapport. 6 September:5. [ Links ]

VAN ZYL, SJJ. & LIGTHELM, A. 1998. Profile study of Spaza retailers in Tembisa, Research report 249, Bureau of Market Research, Pretoria: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

VIRCHEZ, J. & CACHON, JC. 2004. The impact of mega-retail stores on small retail businesses: the case of Sudbury, Northern Ontario, Canada. Revista Mexicana de Estudios Canadienses (nueva epoca), junio(7):49-62. [ Links ]