Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Strategic implications of the drivers of e-business implementation in developing countries

S PerksI; JK MutetiII; J PietersenIII; JK BoschI

IDepartment of Business Management, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University)

IIDepartment of Development Studies, Catholic University of Eastern Africa

IIIDepartment of Statistics, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

Electronic business (E-business) is one of the most significant opportunities that new computing technologies present to business firms. The primary research objective of this study was to determine the drivers of E-business implementation in a developing country, such as Kenya.

Three conceptual models supported this study: the Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) adoption model of Iacovou, Benbasat and Dexter (1995), the Fillis, Johansson and Wagner (2004a) model on E-business adoption, and the Bosch, Tait and Venter (2006) business environment model. Based on the secondary sources a hypothetical model depicting thirteen variables was constructed. A structured questionnaire was administered via e-mail or a hard copy and 466 usable responses were obtained. The validity of the measuring instrument was confirmed using confirmatory factor analysis and Cronbach alpha coefficients confirmed the inter-item reliability of the identified variables. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) confirmatory statistical techniques were used to analyse the model fit and statistically significant relationships.

As the hypothetical model only showed one statistically significant relationship, the hypothetical model was re-specified into three sub models, namely: micro-, market-, and macro environmental models depicting the E-business implementation drivers. Four drivers for E-business implementation were identified namely: strategic intent, trading partner readiness, IT infrastructure and international orientation.

Key phrases: E-business implementation, ICT, E-business strategies, Internet evolution, digital divide

1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

The internet evolution, as a spinoff from the Knowledge Economy, has been one of the greatest changes and one of the fastest growing consumer services the world has so far experienced since the advent of the industrial revolution (Mutula 2002:504). Laudon and Traver (2002:109) identified three phases that characterised the evolution of the Internet since its inception, namely the innovation, institutional and commercialisation phases.

The commercialisation phase was epitomised by government agencies that encouraged private corporations to acquire and expand both the Internet infrastructure and local service network users at large and led to the actual starting phase of E-commerce activities. Most business firms have incorporated the Internet as part of their information technology strategy and are today involved in some type of E-business (Daft 2010:426).

Two previous studies explored in this study are the:

• Iacovou, Benbasat and Dexter (1995:467) conceptual model focussing on electronic data interchange and the adoption of E-business by small businesses; and

• Fillis, Johansson and Wagner (2004a:184) conceptual model which identified the drivers pertaining to E-business adoption and development in smaller firms.

The drivers in the micro-, market- and macro business environments as discussed by Bosch, Tait and Venter (2006) provided a framework to present the relevant variables in the hypothetical model for E-business implementation.

The potential of contemporary Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) in Kenya is still at present (2009) not yet fully implemented. In spite of this, a significant expansion in usage was experienced through Internet cafés in almost all towns offering telephone services, e-mail facilities and Internet access (International Telecommunication Union 2006:1). Furthermore, it is estimated that Internet users in Kenya are about 3 995 500 people, in other words about 10 percent of the total population (Internet World Stats 2010). These facilities are frequented by certain groups of people, such as professionals and students, but are still not commonly used by the low-income earners who are not English proficient and have low literacy levels. Kenya has 0.03% of global share of internet users and there are 0.071% Google Swahili users in the country (Wikistats 2010).

The purpose of this study is therefore to determine the strategic implications of the drivers impacting E-business implementation in Kenya. Firstly, the problem statement and objectives of the study are provided. A theoretical exposition of the drivers (independent variables) impacting E-business and related concepts supporting the hypotheses will be also be given. Thereafter, the research methodology of the study will be highlighted. The research results will be provided, followed by the main conclusions. The strategic implications of the drivers impacting E-business implementation in developing countries (such as Kenya) will also be indicated. The problem statement and objectives of the study will be highlighted in the next section.

2 PROBLEM STATEMENT AND RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

Porter (2001:65) emphasises that Internet technology becomes strategically significant only when its practical application creates true economic value. Internet technology provides better opportunities for business firms to establish distinctive strategic positioning than did previous generations of information technology. Porter (2001:65) further argues that gaining such competitive advantages does not require a radically new approach to business; rather, it requires building on the proven principles of effective strategy.

Kenya was linked to the Internet and World Wide Web in 1996 (Mutula 2002:470). Since then, there has been significant growth in the Internet usage in Kenya. However, despite some notable developments in the usage of the Internet in Kenya, poor telecommunication service and an inadequate mains power supply structure is still hampering the growth of E-business in the country (International Telecommunications Union 2006:1). Computer hardware, a critical component of an Internet infrastructure, remains expensive, connectivity tariffs are still high and an Internet policy still needs to be developed to oversee the implementation and regulation of the Internet industry in Kenya (Mutula 2001:158).

Besides the external barriers to E-business implementation in Kenya indicated above, several internal barriers to E-business implementation in both developing and developed countries were identified by many authors (Dubelaar, Sohal & Savic 2005: 1254; Fillis et al. 2004a:84; Jones Beynon-Davies & Muir 2003:10; Michael & Andrew 2004:285). These internal barriers include amongst others lack of financial resources; lack of IT expertise; lack of top management support; unready customers and/or business partners; unwillingness to learn new skills; and lack of an IT skill-base. Given the low levels of E-business implementation in Kenya and being a developing country, the problem statement pertaining to this research is:

What are the drivers and strategic implications of E-business implementation in developing countries, such as Kenya?

A number of research objectives were formulated to give effect to the problem statement. The primary objective of the study was to determine the strategic implications of the drivers impacting E-business implementation in developing countries, such as Kenya. The secondary objectives of the study included inter alia:

• to explore literature on E-business implementation drivers;

• to develop an appropriate research instrument to source primary data relating to the drivers of E-business implementation;

• to test the hypothetical model for E-business implementation using SEM methodologies;

• to indicate the strategic implications of the drivers impacting E-business implementation in developing countries, such as Kenya.

3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK FOR E-BUSINESS IMPLEMENTATION

E-business as a concept

Peace, Weber, Hartzel and Nightingale (2002:42) define E-business as the complex fusion of business processes, business applications, and organisational structure necessary to create a high-performance business model. The underlying premise of this definition of E-business that will be used in the study is the ability to share information easily, using technologies such as the Internet, Electronic Data Interchange, and cellular technologies.

Drivers impacting E-business implementation

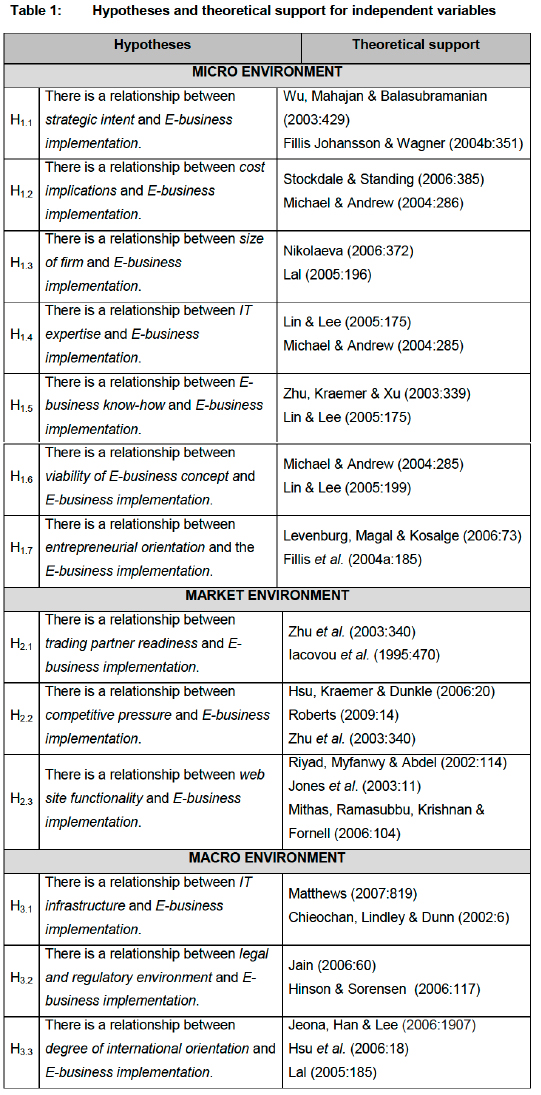

For ease of constructing the hypothetical model for the drivers impacting E-business implementation, the environments identified in Bosch et al. (2006:43) in terms of the micro-, market- and macro environment were used as a framework. Three sets of directional research hypotheses were formulated and then briefly substantiated by secondary sources as can be seen in Table 1. The first set (H1.1 to H1.7) is the drivers within the micro environment; the second set (H2.1 to H2.3) is the drivers within the market environment and the third set (H3.1 to H3.3) is the drivers within the macro environment impacting E-business implementation.

Directional hypotheses were formulated as it was based on prior research findings and secondary sources. The next section highlights the methodology used in this study.

4 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The purpose of the study was to determine the strategic implications of the drivers of E-business implementation in Kenyan firms.

The research approach

Due to the nature of this study, an investigation of the strategic drivers impacting on E-business implementation, the quantitative research approach was adopted. Further, because the research variables were pre-specified based on secondary sources, confirmative factor analysis were employed.

The sample

The relevant population of the research in question was registered business firms operating in Kenya which is estimated to be 10 000 business firms. The non-probability sampling procedure was used and a convenient sample was drawn, purely on the basis of availability and accessibility of the respondents. Registered firms in Kenya that appear in the 2009 edition of the official yellow pages directory and the 2009 members' directory of Kenya Association of Manufacturers comprised the sample.

The only requirement for inclusion in the sample is that the business firm must have implemented E-business practices. As it could not beforehand be established whether these business firms had implemented E-business, it was clearly stated in a covering letter that only business firms that have implemented E-business are allowed to participate. Only 2 550 business firms were invited to participate in the research project via e-mail as the name of a specific person could be linked to the e-mail address. The position of the person that completed the questionnaire could thus be verified and it could be established whether this person was indeed knowledgeable about E-business.

Research instrument

A structured text-based research instrument was designed and the respondents were requested to rate the statements pertaining to E-business implementation on a five-point Likert scale anchored from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). A five point Likert scale was used given the educational levels of the respondents. Biographic information on the responding business firms was also solicited. The research instrument was pilot tested to assess the initial validity and reliability. The research instrument comprises of two sections:

• Section A gauged the opinions of respondents on the strategic implications of the drivers impacting E-business implementation.

• Section B canvassed biographical data of the business firms.

Data collection

For the data collection phase, the Internet based survey tool known as the "my web-survey" was used for the study. A total of 2 550 emails were sent to business firms requesting them to access the Internet based questionnaire through the link, "My web survey". Of all the responses, after data cleaning, there were 466 usable questionnaires.

Data analysis

The data analysis comprised of three phases, namely:

• Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients to verify the consistency of the inter-item reliability of the research instrument;

• Confirmatory factor analysis to assess the discriminant validity of the measuring instrument. Items that did not load to a significant extent (loadings > 0.30) and on a unique factor were deleted. After insignificant loadings (loadings < 0.30) were deleted, the confirmatory factor analysis was repeated to assess the discriminant validity of the measuring instrument. Confirmatory factor analysis was used as the drivers (independent variables) identified were identified in previous research studies.

• Structured equation modelling for fitting the model using goodness-of-fit tests to determine if the hypothetical model being tested should be accepted or rejected. Six goodness-of-fit tests were utilised: global fit measures such as Chi-square (X2) and normed Chi-square; Non-centrality Fit Indices such as Steiger-Lind Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) index and Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR); and single sample fit indices such as Jöreskog GFI and Bentler Comparative Fit Index (CFI). Structured equation confirmatory analysis was also used for the validation of the hypothetical model to indicate the statistically significant relationships.

Although the hypothetical model indicates a good or acceptable fit, only one statistically significant relationship was found between International orientation and E-business implementation. It was then decided to re-specify the original model into three smaller sub models according to the micro-, market- and macro environmental drivers for E-business implementation. Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black (2006:741) suggest that simpler models can be tested with smaller samples and be each subjected each to SEM individually. The items (statements) linked to the drivers (independent variables) in the original model remained the same as those in the sub models. As the hypothesised relationships of the three sub models were based on the original hypothetical model, it was deemed unnecessary to again operationalise the research variables or to assess the reliability and validity of the research instrument. The empirical results are presented in the next section.

5 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Results of the biographical data

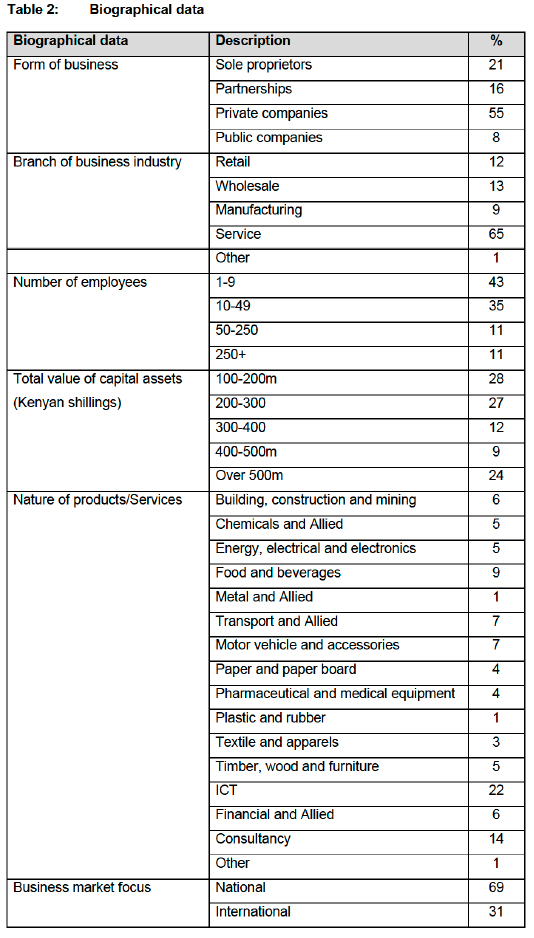

Table 2 is a composite table reflecting on the biographical data.

As can be seen in Table 2, most respondents were private companies, service businesses, selling a variety of products or services, with less than 50 employees and with a national market focus.

Results of the reliability and validity of the factors

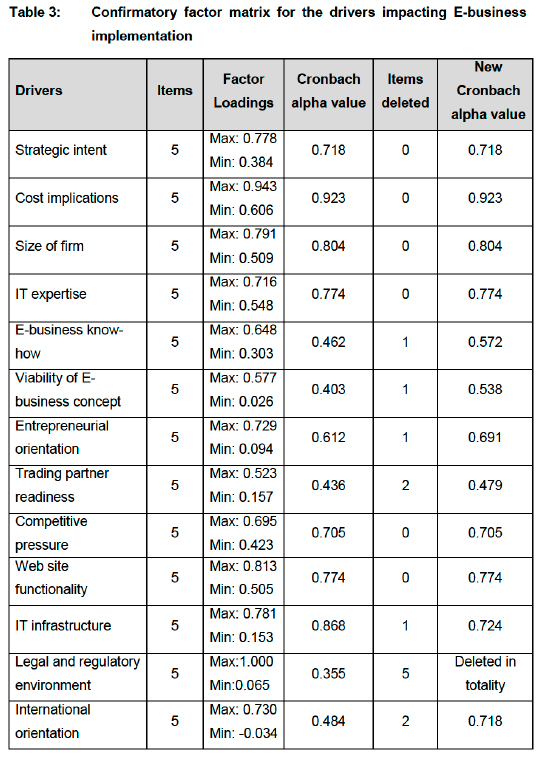

Table 3 shows the confirmatory factor matrix for the drivers impacting E-business implementation in Kenya.

The Cronbach alphas of trading partner readiness and legal and regulatory environment are 0.479 and 0.355 respectively and seem to violate the reliability of the instrument given the threshold of 0.50 according to Athayde (2003:10). The 0.479 coefficient for trading partner readiness was retained, as it can be rounded to 0.50. Based on the results of the confirmatory factor analyses the independent variable (driver) legal and regulatory environment was dropped from the analysis. Based on the permissible threshold stated by Athayde (2003:10), the reliability of the factors in the research instrument can be described as acceptable.

With regard to the discriminate validity of the research instrument, the pattern coefficients in Table 3 demonstrated loadings ranging between 0.303 and 0.943. One item in legal and regulatory environment showed convergent validity of 1.000. The other items demonstrate loadings less than the permissible 0.30 and thus illustrate that the scale demonstrates the relationships shown to exist based on theory and/or prior research. Consequently, the validity of this scale was confirmed and was used to assess the drivers of E-business implementation for a developing country, such as Kenya. Validity was further enhanced by: ensuring that the overall research design of the study was sound; the most relevant research procedures were adopted; appropriate samples were drawn; and suitable statistical procedures were followed.

Results of the goodness-of-fit of the hypothetical model

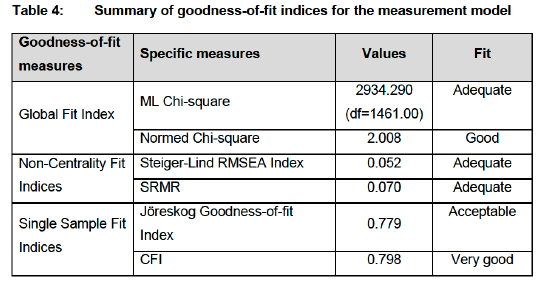

Table 4 gives a summary of SEM of the goodness-of-fit measures for the hypothetical model.

The ML Chi-square (X2) value is less than the cut-off point of three suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (1988), thus indicating a fairly adequate fitting model. The Normed Chi-square is smaller than the three thresholds, thus indicating a good fitting model. The RMSEA is an adequate fit to the data according to Browne and Cudeck (1993:141) who regard values smaller than 0.05 as a good fit, values between 0.05 and 0.08 as adequate fit, and values between 0.08 and 0.10 as a mediocre fit. The SRMR is lower than the 0.8 threshold recommended by Müller (2003), thus qualifying as an adequate fit.

The Jöreskog GFI value is lower than the 0.90 threshold recommended by Jöreskog and Sörbom (1996) but is still acceptable. The CFI can be regarded as a moderately good fit Bagozzi and Yi (1988) regards one as a very good fit. With regard to the results for normality, a significant Mardia's coefficient of 309.389 was found which is much higher than the recommended value of 3.102 by Mardia and Kanazawa (1983:569). Therefore there is significant non-normality.

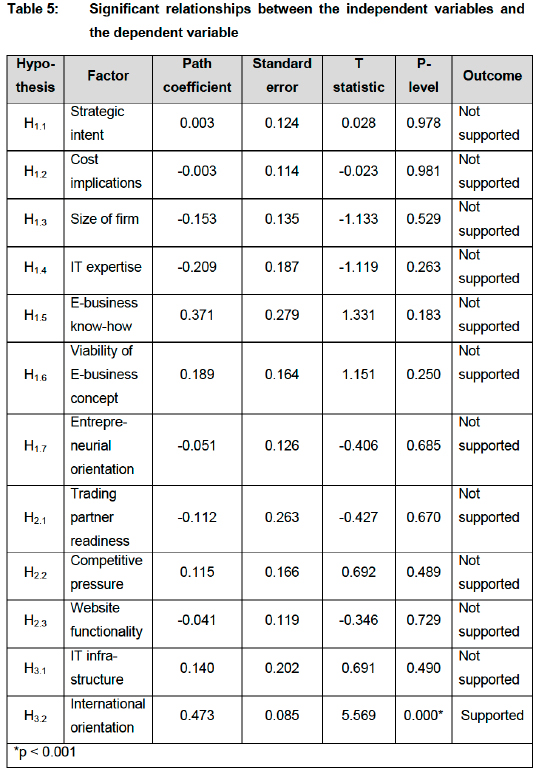

Results of the path coefficients and statistically significant relationships in the hypothetical model

Table 5 outlines the estimates of the path coefficients and the statistically significant relationships between the driver (independent variables) and E-business implementation (dependent variable) in the hypothetical model.

As shown in Table 5 only one significant relationship was found between the independent variable International orientation and the dependent variable E-business implementation. This has indicated the need to re-specify the hypothetical model into three sub-models as SEM relies on tests which are sensitive to sample size as well as to the magnitude of differences in covariance matrixes. A sample of 466 might deem inadequate for the number of independent variables in this research study (Marsh, Balla & McDonald 1988).

Result of the model re-specification

It must be noted that with the re-specification, the variable legal and regulatory environment was once again eliminated based on the unacceptable Cronbach alpha value.

Results of the micro environment sub model

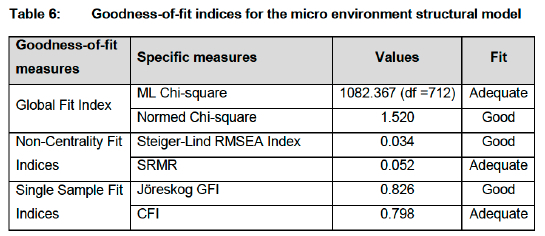

Table 6 shows the SEM results of the re-specified micro environment structural model.

The ML Chi-square (X2) indicates an adequate fitting model. The Normed Chi-square value also suggests a good fitting model. The RMSEA can be regarded as an adequate fit. The SRMR value qualifies as a good fit. The Jöreskog GFI indicates a good fitting model. The CFI can be regarded as an adequate fit. The goodness-of-fit results as presented show evidence of a good or acceptable fit and it was deemed unnecessary to make any modifications to the model. With regard to the results for normality, a significant Mardia's coefficient of 85.82 was found for the micro environmental model which is much higher than the recommended value of 3.102 by Mardia and Kanazawa (1983:569). Therefore there is significant non-normality.

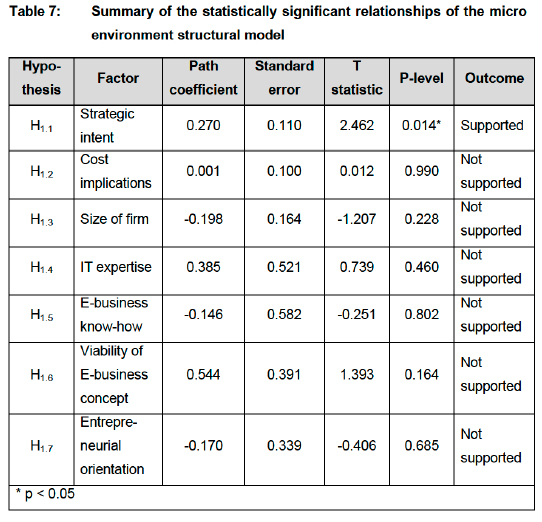

Table 7 outlines the estimates of the path coefficients and the statistically significant relationships between the driver (independent variables) and E-business implementation (dependent variable) in the micro environment structural model.

As shown in Table 7 only one significant relationship was found between the independent variable strategic intent and the dependent variable E-business implementation.

Results of the market environmental sub model

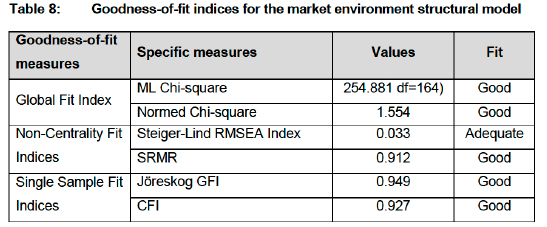

The goodness-of-fit indices for the market environment structural model are reported in Table 8.

Both the ML Chi-square (X2) and Normed Chi-square indicate a good fitting model. The RMSEA suggests an adequate fit. The SRMR value indicates a good fitting model. The Jöreskog GFI value and the CFI value show a good fitting model. The results therefore show evidence of a good or adequate fit. It was thus deemed as unnecessary to make any modifications to the model. With regard to the results for normality, a significant Mardia's coefficient of 32.614 was found for the market environmental model which is much higher than the recommended value of 3.102 by Mardia and Kanazawa (1983:569). Therefore there is significant non-normality.

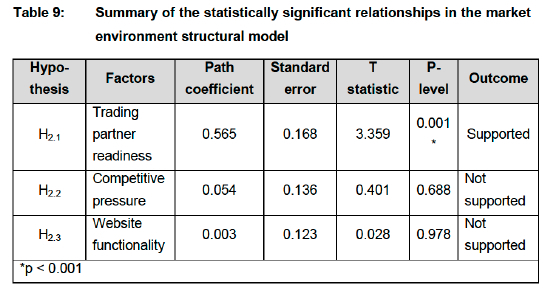

Table 9 outlines the estimates of the path coefficients and the statistically significant relationships between the driver (independent variables) and E-business implementation (dependent variable) in the market environment structural model.

As shown in Table 9 only one significant relationship was found between the independent variable trading partner readiness and the dependent variable E-business implementation.

Results of the macro environmental sub model

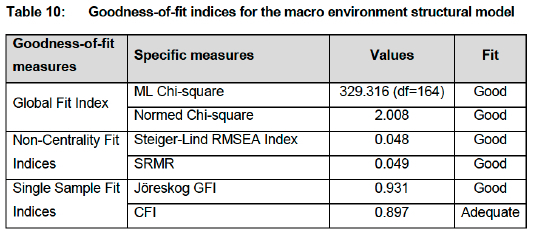

The goodness-of-fit indices for the macro environment structural model are shown in Table 10.

The ML Chi-square (X2) and Normed Chi-square values indicate a good fitting model. The RMSEA and the SRMR values can also be regarded as a good fit. The Jöreskog GFI value indicates a good fitting model. The CFI can be regarded as an adequate fit. The results show evidence of a good or adequate fit and any modifications to the model was thus unnecessary. The results for the study suggested that a significant Mardia's coefficient of 40.436 was found which is much higher than the recommended value of 3.102 by Mardia and Kanazawa (1983:569). Therefore there is significant non-normality.

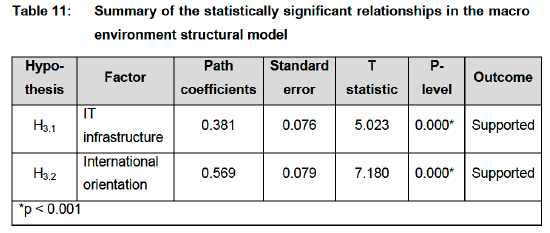

Table 11 shows the results of the statistically significant relationships in the macro environment structural model including the hypotheses testing.

As can be seen in Table 11 both independent variables (IT infrastructure; International orientation) had statistically significant relationships with the dependent variable E-business implementation. The next section will highlight the conclusions made from the given results.

6 ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS

The analysis of the findings of the demographic data will be first presented.

Analysis of the findings of the demographic data

The data showed that more than half of the 466 respondents were sole proprietors, in the service industry with as many as 35% employing between 10 to 49 employees (can be regarded as small businesses). Most of the respondents were in the ICT sector (21.7%) followed by consultancy (15.3%) and food and beverages (8.6%). The majority of the participating firms had less than 100 million Kenyan shillings worth of capital assets with only 8% of the sample indicating assets over 500 million Kenyan shillings.

Analysis of the findings of the reliability and validity of the identified factors

Table 3 shows that strategic intent, IT expertise, E-business know-how, entrepreneurial orientation, competitive pressure, website functionality, international orientation and IT infrastructure indicate acceptable levels of reliability. Cost implications and size of firm indicate a high level of reliability. Viability of E-business and trading partner readiness were retained as their Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients could be rounded to the threshold of 0.5.

The findings of legal and regulatory framework demonstrate a lack of evidence of convergent validity with all items, but one. As the scale returned a low Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of 0.355, it was excluded from further analysis. All the other findings illustrate that the scale demonstrates the relationships shown to exist based on theory and/or prior research and can thus be regarded as valid.

Analysis of the findings of the goodness-of-fit results

The hypothetical- and subsequent three sub-models indicate acceptable or good fit indices. No modifications to the model(s) were thus necessary.

Analysis of the findings of the statistically significant relationships

Only one statistically significant relationship was found between the independent variable International orientation and the dependent variable E-business implementation in the hypothetical model. This has indicated the need to re-specify the hypothetical model into three sub-models. After re-specification of the hypothetical model, four statistically significant relationships were found within the three sub-models. These results are concluded below.

• Strategic intent

In the micro environment structural model a statistically significant relationship was found between strategic intent and E-business implementation indicating that strategic intent can be regarded as a driver for E-business implementation. Respondents indicated that E-business implementation can create more value for both customers and suppliers (Jun & Cai 2003:193).

Furthermore, the existence of strategic insight among top management is an important stimulant to E-business adoption (Wymer & Regan 2005:440). Moreover, positive attitudes of top managers of business firms play a central role in determining the success of E-business implementation strategies (Wu et al. 2003:429).

Trading partner readiness

In the market environment structural model only one statistically significant relationship was found between trading partner readiness and E-business implementation. Therefore trading partner readiness seems a driver for E-business implementation. Respondents indicated that the level of E-business readiness impacts the commitment to E-business implementation (Stockdale & Standing 2006:384).

The respondents indicated that E-business implementation can lead to improved relations with their trading partners such as suppliers and customers (Jun & Cai 2003:193). Furthermore, both suppliers and customers had to acquire E-business capacity to engage in E-business (Zhu et al. 2003:340). Respondents also indicated that trading partners should also understand the benefits by going the EDI route (Zhu et al. 2003:340).

• IT infrastructure

In the macro environment structural model a statistical significant relationship was found between IT infrastructure and E-business implementation. IT infrastructure can thus be regarded as a driver for E-business implementation. The respondents indicated that if Internet services are affordable it warrants E-business implementation.

The respondents regard the reliability of Internet accessibility as a requirement for E-business implementation (Mutula 2005:126), as well as the quality of services offered by ISPs (Stockdale & Standing 2006:385). Respondents also indicated that the quality of ISPs and range of services offered by the ISPs played a decisive role in whether to implement E-business or not (Mutula 2005:126).

• International orientation

In the macro environment structural model a statistically significant relationship was found between International orientation and E-business implementation. International orientation can thus be regarded as a driver for E-business implementation. The respondents indicated that as firms expand globally, they tend to have a greater incentive to use E-business to leverage their existing IT capabilities for competitive advantage (Xu, Zhu & Gibbs 2004:16). Respondents also indicated that E-business implementation in Kenya has been prompted by the growth of foreign trade, or global markets (Ruzzier, Hisrich & Antoncic 2006:476). It was also indicated that small firms regard E-business as a way to establish international business relationships. Respondents indicated that with increased internationalisation of customers and markets, managers are concerned with developments in both domestic- and international markets as it creates both opportunities and competitive challenges for firms seeking profitable growth (Ruzzier et al. 2006:477).

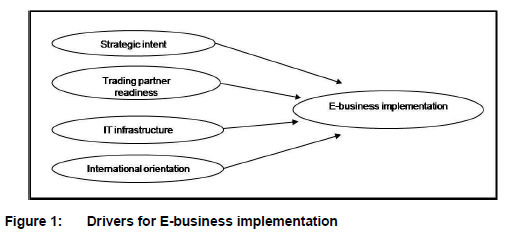

To summarise, the findings indicated that there seem to be more drivers for E-business implementation in Kenya in the macro environment than in the micro- or market environment. Figure 1 indicates illustrates the drivers for E-business implementation in developing countries.

The next section outlines the strategic implications for E-business implementation in developing countries, such as Kenya.

7 STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS FOR E-BUSINESS IMPLEMENTATION IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

The following strategic implications for E-business implementation in developing countries are based on the secondary sources consulted for the literature review, as well as the findings of the empirical results.

Strategic intent

Business firms in developing countries should be encouraged to develop a strategic plan if considering E-business implementation. Managers should display a synergy between human- and technical skills in order to gain maximum returns from implementing E-business. Business firms also need to target the "Diaspora" in promoting E-business activities as they have the means and infrastructure to engage in E-business activities. The focus in business firms wishing to implement E-business should be on developing E-leadership- and E-management skills.

Trading partner readiness

As the main requisite for E-business implementation is a website, business firms should be encouraged to obtain a website as it is an important medium to sell products directly to the customers or to convey informative information. Government in developing countries should work towards ensuring that the infrastructure is in place to provide fast and reliable Internet connectivity at a reasonable cost. Furthermore, the reliability of telephone links should be ensured.

Competent human resources must be obtained in order to reap the benefits of ICT to its fullest potential. Business firms should put in place a rigorous communication plan in conjunction with their trading partners. Business firms in developing countries should also tie their IT architectures to supply chain management and logistics so as to create internal and external collaboration functionality, which is the essence of E-business.

IT infrastructure

The government in developing countries should consider increasing investments in the ICT sector in order to make internet services affordable, especially to SMEs. They should also ensure that internet services are reliable and of a high quality. A master infrastructure development plan should be compiled to deal with issues on ICT infrastructure. Developing countries should seek assistance from international and regional development funding organisations like the World Bank and the African Development Bank to build such infrastructure and nurture E-business development.

Governments also need to investigate the possibility of using spare bandwidth of the fibre optical infrastructure to transmit electricity and data to firms in rural areas. Furthermore, governments should set up E-business support cells, tele-centers and community information centres for business applications at local levels as this would promote E-business applications, especially so in SMEs.

International orientation

Business firms in developing countries wishing to engage in worldwide market activities should consider issues such as product characteristics, logistics, delivery, maintenance, support and other services prior to E-businesses implementation. These business firms must first establish whether they have the infrastructure E-business requires by obtaining information from the Internet. The government of the developing country should support E-business strategies of business firms and possible resistance to change should be investigated, especially when technology threatens conventional structures.

Business firms should be informed that E-business can give them a global visibility across an extended network of trading partners and make them respond quickly to a range of business conditions, from changes in customer demand to resource shortages. Governments should communicate the advantages of E-business in the global market to business firms in developing countries and point out that if they wish to increase their firm size (sales turnover) and obtain a competitive advantage they should have an international or even global market orientation.

8 LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The following possible limitations of this study are acknowledged:

• The methodology required trade-offs that may limit the use of the data and interpretation of the results.

• The findings should not be seen to offer conclusive findings as it focused on E-business implementation, which constantly changes due to technological advances in a dynamic business environment.

• Since this study is a non-experimental study, the final models cannot be interpreted as causal models.

• Cross-sectional designs only allow for the evaluation of relationships among variables at one point in time and do not allow for autoregressive effects or time lags.

• The managers in Kenya are regarded as the most educated to complete the questionnaire, but it might have led to some bias views about E-business implementation.

• Most of the theories on E-business reviewed by this study, and used to build the hypotheses for the research were based on E-business technology adoption in developed countries, as no sources referring to developing countries could be found.

• It seemed that SEM methodologies are not suitable for use in developing countries as only four statistically significant relationships were found.

In spite of the possible limitations the research can be regarded as valuable as no such studies have been conducted on E-business in developing countries. The strategic implications clearly outline the issues at stake to which developing countries should pay attention to if wishing to implement E-business and compete in the global context. The following suggestions are made for future research:

• Exploring E-business implementation, in particular the problems experienced in Kenya, utilising the qualitative paradigm with in-depth case studies of a few selected firms.

• Investigating the differences and similarities of factors impacting on E-business implementation in a developed country as compared to a developing country.

Finally, to conclude, it must be noted that the macro environment seems to influence E-business implementation in Kenya more so than forces in the micro- or market environment. This was confirmed by the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (2007:1) which indicates that Kenya's business environment poses major challenges to business firms, rendering them non-competitive and therefore unable to take advantage of opportunities emerging from globalisation.

The World Bank (2007:6), ranked Kenya 72 out of 178 countries, after Mauritius (27th), South Africa (35th) and Botswana (51th) in terms of the ease of doing business with indicators such as business regulation and protection of property rights. Furthermore, the World Economic Forum (2007:8) global competitiveness index ranked Kenya 97 out of 130 during 2007. According to the World Economic Forum (2007:23), Kenya is an interesting case because its strengths lie in those areas normally reserved for countries at higher stages of development. For this reason Kenya was chosen for this study and the results could thus also apply to other developing countries.

The strategic focus of Kenya's ICT Policy, which is in place since 2008, was to simultaneously target the development of the ICT sector and to use it as a broad based enabler in the achievement of national developmental goals. Despite the reality that Kenya was among the first countries to implement Internet connectivity in Africa, there are a number of constraints obstructing the development of Internet services and hence E-business development (Yabs 2007:38). These constraints have been highlighted in this study.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ATHAYDE R. 2003. Measuring young people's attitudes to enterprise. [Internet: www.kingston.ac.uk/sbrc; downloaded on 2009-10-01. [ Links ]]

BAGOZZI RP. & YI Y. 1988. The evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1): 74-94. [ Links ]

BOSCH JK, TAIT M & VENTER E (eds). 2006. Business management: An entrepreneurial perspective. Port Elizabeth: Lectern. [ Links ]

BROWN M & CUDECK R. 1993. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Newbury Park: Sage. [ Links ]

CHIEOCHAN O, LINDLEY D & DUNN T. 2002. Factors affecting the use of information technology in Thai agricultural cooperatives. Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, 2(1): 1-15. [ Links ]

DAFT R. 2010. The new era of management. 9th Edition. Australia: Thompson. [ Links ]

DUBELAAR C, SOHAL A & SAVIC V. 2005. Benefits, impediments and critical success factors in B2C E-business adoption. Technovation, 25:1225-1262. [ Links ]

FILLIS I, JOHANSSON U & WAGNER B. 2004a. Factors impacting on E-business adoption and development in the smaller firm. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 10(3): 178-191. [ Links ]

FILLIS I, JOHANSSON U & WAGNER B. 2004b. A qualitative investigation of smaller firm E-business development. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 11(3): 349-361. [ Links ]

HAIR JF, ANDERSON RE, TATHAM RL & BLACK, W.C. 2006. Multivariate data analysis. 6th Edition. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

HINSON R & SORENSEN O. 2006. E-business and small Ghanian exporters. Online Information Review, 30(2): 116-138. [ Links ]

HSU P, KRAEMER K & DUNKLE D. 2006. Determinants of E-Business use. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 10(4): 9-45. [ Links ]

IACOVOU CL, BENBASAT I & DEXTER AS. 1995. Electronic Data Interchange and small organisations: Adoption and impact of technology. MIS Quarterly, 19(4): 465-485. [ Links ]

INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION. 2006. World telecommunication/ ICT development report: Measuring ICT for social and economic development. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. [ Links ]

INTERNET WORLD STATS. 2010. Internet usage statistics for Africa. [Internet: http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats1.htm; downloaded 2010-10-07. [ Links ]]

JAIN P. 2006. Empowering Africa's development using ICT in a knowledge management approach. The Electronic Library, 24(1): 51-67. [ Links ]

JEONA B, HAN K & LEE M. 2006. Determining factors for the adoption of e-business: The case of SMEs in Korea. Applied Economics, 38: 1905-1916. [ Links ]

JONES P, BEYNON-DAVIES P & MUIR E. 2003. E-business barriers to growth within the SME Sector. Journal of Systems & Information Technology, 7(1): 1-5. [ Links ]

JÖRESKOG KG & SÖRBORN D. 1996. LISREL 8: User's Reference Guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International Inc. [ Links ]

JUN M & CAI S. 2003. Key obstacles to EDI success: From the US small Manufacturing companies' perspective. Industry Management and Data Systems, 103(3): 192-203. [ Links ]

KENYA ASSOCIATION OF MANUFACTURERS. 2007. Establishing the Challenge. Nairobi: Kenya Association of Manufacturers. [ Links ]

LAL K. 2005. Determinants of the adoption of E-business technologies. Telematics and Informatics, 22(05): 181-199. [ Links ]

LAUDON K & TRAVER C. 2002. E-commerce. New Delhi: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

LEVENBURG NM, MAGAL S & KOSALGE P. 2006. An exploratory investigation of organizational factors and E-business motivations among SMFOEs in the US. Electronic Markets, 16(1): 70-84. [ Links ]

LIN H & LEE G. 2005. Impact of organizational learning and knowledge management factors on E-business adoption. Management Decision, 43(2): 171-188. [ Links ]

MARDIA KV & KANAZAWA M. 1983. The null distribution of multivariate kurtosis. Communications in Statistic Simulation and Computation, 12(1): 569-576. [ Links ]

MARSH HW, BALLA JR, & MCDONALD RP. 1988. Goodness of fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: the effect of sample size. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3): 391-410. [ Links ]

MATTHEWS P. 2007. ICT assimilation and SME expansion. Journal of International Development, 19: 817-827. [ Links ]

MICHAEL T & ANDREW M. 2004. SMEs and E-business. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 11(3): 280-289. [ Links ]

MITHAS S, RAMASUBBU N, KRISHNAN M & FORNELL C. 2006. Designing Web Sites for Customer Loyalty across Business Domains: A Multilevel Analysis. Journal of Management Information Systems, 23(3): 97-127. [ Links ]

MÜLLER H. 2003. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2): 23-74. [ Links ]

MUTULA S. 2001. The IT environment in Kenya: Implications in Public Universities. Library Hi Tech, (19) 2:155-166. [ Links ]

MUTULA S. 2002. Internet connectivity and services in Kenya: current developments. The Electronic Library, 20(6): 466-472. [ Links ]

MUTULA S. 2005. Peculiarities of the digital divide in sub-Saharan Africa. Electronic Library and Information Systems, 39(2): 122-138. [ Links ]

NIKOLAEVA R. 2006. E-commerce adoption in the retail sector: empirical insights. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 34(4/5): 369-387. [ Links ]

PEACE G, WEBER J, HARTZEL K & NIGHTINGALE J. 2002. Ethical Issues in E-Business: A proposal for creating the E-Businesses principles. Business and Society Review, (107) 1:41-60. [ Links ]

PORTER M. 2001. Strategy and the Internet. Harvard Business Review, 79(3): 62-78. [ Links ]

RIYAD E, MYFANWY T & ABDEL M. 2002. A Cross-Industry review of B2B critical success factors. Internet research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 12(2): 110-123. [ Links ]

ROBERTS B. 2009. Stakeholder power in E-business adoption with a game theory perspective. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 4(1): 12-22 [ Links ]

RUZZIER M, HISRICH R & ANTONCIC B. 2006. SME internationalization research: past, present, and future. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(4): 476-497. [ Links ]

STOCKDALE R & STANDING C. 2006. A classification model to support SME e-commerce adoption initiatives. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(3): 381-394. [ Links ]

WIKISTATS. 2010. Kenya. [Internet: http://stats.wikimedia.org; downloaded on 2010-10-18. [ Links ]]

WORLD BANK. 2007. Doing business 2008. World Bank. Washington, D.C. [ Links ]

WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM. 2007. The Africa competitive report 2007. World Economic Forum. Geneva. [ Links ]

WU F, MAHAJAN V. & BALASUBRAMANIAN S. 2003.An analysis of e-business adoption and its impact on business performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(4): 425-447. [ Links ]

WYMER S & REGAN E. 2005. Factors Influencing e-commerce Adoption and Use by Small and Medium Businesses. Electronic Markets, 15(4): 438-453. [ Links ]

XU S, ZHU K & GIBBS J. 2004. Global Technology, Local Adoption: A Cross-Country Investigation of Internet Adoption by Companies in the United States and China. Electronic Markets, 14 (1): 13-24. [ Links ]

YABS, J. 2007. International business operations in Kenya: a strategic management approach. Nairobi: Lelax Global Ltd. [ Links ]

ZHU K, KRAEMER K & XU S. 2003. E-business adoption by European Firms: A cross-country assessment of the facilitators and inhibitors. European Journal of Information Systems, 12(4): 251-268. [ Links ]