Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Social capital for business start-ups: perceptions of community support and motives

B UrbanI; G ShawII

IWits Business School, University of Witwatersrand

IIChair in Entrepreneurship, University of Fort Hare

ABSTRACT

This article builds on past research which indicates that entrepreneurial activity does not occur in a vacuum, but instead is rooted in cultural and social contexts, specifically within webs of community networks. Recognising the importance of the social capital for entrepreneurs, the purpose of this article is to provide descriptive evidence of community support perceptions and to interrogate motives for business start-ups. Following a literature review on social capital, entrepreneurship, community norms, and motives for business start-ups, a sample consisting of 180 respondents who currently own and manage a new business in a wide range of businesses were surveyed. Descriptive and inferential statistics were calculated and based on the sampling characteristics a distinct entrepreneurial profile emerges. The main finding of this article, in that significant differences are detected across race and language groups on motives for start-ups is important, since entrepreneurs act as catalysts of economic activity and the entrepreneurial history of a community is imperative. Central to strategic actions initiated by the South African government, is the broadening of community support programmes and the streamlining of support institutions.

Key phrases: Business start-ups, entrepreneurship, community, norms, motives

INTRODUCTION

Every new venture, from mom-and-pop convenience stores to Silicon Valley superstars such as Google, starts with an 'investment' form the founders themselves or the so called 3Fs (family, friend, or foolhardy strangers) (Bosma & Levie 2009:52). This community of investors is vital to the start-up process, with perceptions of social capital provided by a community being essential to entrepreneurial start-ups. Moreover by practicing social performance obligations and sustainable development principles, small, medium enterprises (SMEs) need to be responsive towards the concerns of community (Smith & Perks 2010:90).

The contemporary study of entrepreneurship and the importance of social embeddedness can be traced to the works of Max Weber (1948) and Joseph Schumpeter (1934). Both argued that the source of entrepreneurship behaviour lay in the social structure of societies and the value structures they produce. Earlier research on entrepreneurship has suggested that local entrepreneurs are socialized in the ways of indigenous populace and thus may display the broad based values of the society in which they live (Steensman, Marino & Weaver 2000; Thornton 1999). An entrepreneur's choice is thought to be influenced by 'others' chosen paths, and hence entrepreneurship is an interdependent act. Past studies have explicitly used the concept of 'outsiders' to comprehend entrepreneurship. Models of collective behaviour indicate that an individual's decision does not depend on his or her preferences alone but is influenced by what others in the community also choose (Bygrave & Minniti 2000). Hence entrepreneurship is a self-reinforcing process. Entrepreneurship leads to more entrepreneurship and the degree of entrepreneurial activities is outcome of a dynamic process in which social habits (entrepreneurial memory) are as important as legal and economic factors. Thus entrepreneurs act as catalysts of economic activity and the entrepreneurial history of a community is important. Research supports this notion of community influence and has found that small-business entrepreneurs who contribute personally and professionally to their community, and who are supported by their community, are more likely to be successful (Kilkenny, Nalbarte & Besser 1999). This notion of community support may also be captured as the 'Batho Pele' principle in the broader South African context (Mofolo 2009).

In South Africa, the growth and development of the small and micro-enterprise business sector, in particular, has been identified by many stakeholders as being of utmost importance in an effort to create employment and address poverty (SAIRR 2007). SMEs are pivotal to the growth and development of the South African economy, and inextricably linked to economic empowerment, job creation, and employment within disadvantaged communities (Gauteng Provincial Government 2008). New ventures offer the promise of empowering marginalized segments of the population. Indeed if entrepreneurship is not valued in the community or culture of a particular country, then not only will it be associated with criminality and corruption but also other forms of economic encouragement will prove ineffective (Baumol 1996).

STUDY PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES

This article builds on past research which indicates that entrepreneurial activity does not occur in a vacuum, but instead is rooted in cultural and social contexts, specifically within webs of community networks (Chan, Bhargava & Street 2006; Stanley & Dampier 2007). In the series of Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) reports, cultural and social norms are emphasized as the major strength of entrepreneurial orientation and seem to be the differentiating factor for high levels of entrepreneurial activity in different countries (Minniti & Bygrave 2003). Recognising the importance of the social context, in particular the perceptions of community support for new business start-ups, the purpose of this study is to provide descriptive evidence of community support perceptions and to interrogate motives for business start-ups.

Resonating with past studies, the research question this article advances is on the subject of community support perceptions in terms of business start-ups. For the purposes of the article entrepreneurial behaviour is analysed in terms of start-up motives. The paper proceeds with a literature review on social capital, community norms, culture and motives. Hypotheses are then formulated and statistically tested.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Social capital

Adler and Kwon (2002), argue that the breadth of the social capital concept reflects a primordial feature of social life - namely, that social ties of one kind (e.g., friendship) often can be used for different purposes (e.g., moral and material support, work and social advice). Social capital's sources lie - as do other resources' - in the social structure within which the actor is located. Social capital explains the ability of actors to extract benefits from their social structures, from their networks and memberships, and particularly where social and relational structures influence market processes. The study of social capital and its impact on economic decision-making and actions stems from classic literatures in economics and sociology (Audretsch & Keilbach 2004; Granovetter 1973). Social capital is often construed as multidimensional, which occurs at both the individual and the organizational levels (Davidson & Honig 2003:303). Moreover social capital is cumulative, leads to benefits in the social world, and can be converted into other forms of capital (Cooper & Denner 1998).

Globally and in South Africa, the business environment is moving towards networks, open markets, mobile labour and information abundance (Mansfield, Fourie & Gevers 2005). These driving forces and in particular social support has been recognised in organisational studies as playing an important role in monitoring the effects of role overload and turnover intention (Pienaar, Sieberhagen & Mostert 2007), as well as how work-based social support may have a significant buffering effect on occupational stress (Allen & Ortlepp 2000). From an entrepreneurial perspective, social capital provides networks that facilitate the discovery of opportunities, as well as the identification, collection and allocation of scarce resources (Davidson & Honig 2003). One can differentiate social from other types of resources by the specific dimension of social structure underlying social relations. Social networks provided by extended family, community-based or organizational relationships are often theorized to supplement the effects of education, experience and financial capital (Greve & Salaff2003).

Social capital is often explained in terms of social exchange. This allows for better understanding the effects of exchange ties on performance. Exchange effects may range from the provision of concrete resources, such as a loan provided by a mother to her daughter, to intangible resources, such as information about the location of a new potential client. Social exchange may occur between the following players:

• Bankers and other investors help new firms get started.

• Central and local governments provide support for those starting new firms.

• Community groups provide support for those starting businesses.

• Educational establishments encourage individuals to be independent and start their own businesses.

• Media encourage entrepreneurship through promoting role models and highlighting entrepreneurial events.

• Family and kin who have started new firms give advice and assistance.

• Role models who are well respected people who have themselves made a success of starting a new business provide support and encouragement (Davidsson & Honig 2003:307).

Entrepreneurship and community support

The formation of entrepreneurial start up ventures is often cited as the most effective way to relocate labour and capital in a transition economy (Luthans, Stajkovic & Ibrayeva 2000). Recent research among European countries in transition emphasizing the point that entrepreneurship exists in every country; this spirit can be fostered with an appropriate framework. Not only does the macroeconomic (national economic growth rates) environment together with the more immediate business environment (such as education and training) effect the competitiveness and productivity of a country, but more specifically enduring national characteristics have been predicted to have an impact on the level of entrepreneurship activity (Von Broembsen, Wood & Herrington 2005).

Two broad views are used in the discussion of new venture formation (Davidsson & Wiklund 1997:184): Firstly, the supportive environment perspective or societal legitimization perspective, i.e., prevailing values and beliefs among others may make a person more or less inclined towards new venture formation. Secondly, a relationship may occur because some regions have a larger pool of potential entrepreneurs. This view emphasizes the embeddedness of entrepreneurship in social and structural relationships (Bygrave & Minniti 2000; McClelland 1961).

Reviewing earlier work on community and enterprises, explanations emerge which focus on community as a set of connections and regular patterns of interaction among people sharing common national background or migratory experiences. Membership of associations (as opposed to the group) is voluntary, not compulsory, and these associations do not pursue only narrow ethnic interests. Rather associations operate in the realm of the supposedly civic realm, functioning as cooperatives, credit societies, women's organisation and social clubs. Associations are particularly important in this regard because they not only express differences but also perform the judicial function of settling disputes involving members of the in-group and out-group. To exclude associations is to miss the lesson of the overall implication of ethnic division for civil society (Eghosa & Osaghae 2005).

Communities represent associations which centre round the interests of members of the association and the ethnic community, and include the following: guarantees of social security and protection to members of the in-group; offering 'connections' to job-seekers and workers in places of employment; fostering of linkages between urban dwellers and the rural ethnic home base; production of social and public goods through largely self-help efforts; production of local private capital; propagation and preservation of socio-cultural systems and practices; representation and defence of group identity and interests; and mediation of disputes involving members of the in-group and out-group.

Indeed entrepreneurs are an active part of a community providing mutual, symmetric, reciprocated support (Kilkenny et al 1999). Community enterprise is often considered in the context of traditional economically-relevant characteristics of the location, the business and the entrepreneur. Communities are centred on the notion of 'place', which may be construed as a social evaluation of location based on meaning. These are locations of socialization and cultural acquisition. Place creates a distinct culture, has meaning and both has and creates identities (Flora & Flora 1993).

Cultural and social norms influencing entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs are human beings operating within social systems which define and are defined by cultures (Aldrich & Zimmer 1986). Research on entrepreneurial similarities and differences suggests entrepreneurs across various cultures are more similar to each other than to counterparts in their own countries (McGrath, Macmillan, Ai-Yuan Yang & Tsai 1992). Past research suggests that individuals reflect the dominant values of their national culture, which means they might share some universal traits but others are more cultural or community specific. The extent to which different cultures are similar and different is often based on the implicit assumption that with 'cultural distance', differences in cultures produce lack of 'fit' and hence an obstacle to entrepreneurship (Rijamampianina & Maxwell 2002; Thomas & Mueller 2000). However cultural differences may also be complementary and have positive synergetic effects on investment and performance, for instance, global cooperation demands both concern for performance (masculinity) and concern for relationships (femininity), and the two may be mutually supportive. Some key mechanisms with the potential of closing 'cultural distance' are globalization and convergence, acculturation, and/or cultural attractiveness (Shenkar 2001).

Hofstedes' cultural dimensions1 are useful in identifying which criteria of culture are related to entrepreneurship. (Hofstede 1980; 2001) Based on Hofstede's main cultural dimensions, many African evaluations (Kinunda-Rutashobya 1999; Themba, Chamme, Phambuka & Makgosa 1999) have been devised where strategies are advocated to cultivate a culture conducive to entrepreneurship. In African culture a high level of collectivism has often being ascribed to highly interdependent communities. A concept like 'Ubuntu' (a shared value of community involvement) is in conflict with individualism yet differs from collectivism, where the rights of the individual are subjugated to a common good (Corder 2001). It has been suggested that the African version of collective interdependence does not extend as far as the Japanese model, where the individual largely ceases to exist; instead individuality is reinforced through community (McFarlin, Coster & Mogale 1999).

Studies indicate that African communities are under the strain of the competition between acculturation toward urban, western versus indigenous African value systems (Mpofu 1994). The modernity trend in Africa is evident, which is characterized by an individualistic, rational, and secular view of life as opposed to the traditionalist, collectivist, metaphysical, and moralistic orientation. Somewhat provocatively, it has been suggested that it is difficult for an individual to become a millionaire in Africa because of the emphasis on interdependence through the African collective system (Mwamwenda 1995). Only few Africans who have adopted the Western approach to wealth creation have succeeded to attain the status of a millionaire. Does this mean that Africans and other non-westerners have to acquire classically Western abilities if they are to survive in today's dominant culture, which based on distribution of power is largely western in its inspiration?

Entrepreneurial behaviour is also influenced by a history of family enterprise, findings in this regard are so strong that it is suggested understanding familial influences on business formation may be more important than understanding the influence of any other cultural factors. Family tradition in business inculcates a business culture and may provide greater access to capital and information from within the family. It seems fair to argue that a family background in business offers aspiring entrepreneurs an initial advantage in the form of exposure to business practices and a tacit knowledge of business, by inculcating a business culture prior to business entry (Basu & Altinay 2002).

Entrepreneurial motives for start-ups

A common theme which pervades most entrepreneurship research is that groups adapt to the resources made available by their environments, with substantial variation across societies and time (Aldrich & Waldinger 1990). Equally important are personal motives which affect both start-up decisions and the start-up processes. Many studies focus on aspects of entrepreneurial motivation in relation to starting a venture (Drnovsek & Glas 2002; Douglas & Shepherd 2002), however few studies focus on the determinants of various entrepreneurial motives such as the necessity motive, the independence motive, and wealth motive, and how the incidence of these various motives affects entrepreneurial behaviour (Shane, Locke & Collins 2003).

Personal motives affect both start-up decisions and the start-up processes. Models and theories delineating how motivations influence the entrepreneurial process are copious (Naffziger, Hornsby & Kuratko 1994); one such model explains that the relative magnitude of how much a particular motivator matters, varies depending on which part of the entrepreneurial process is being investigated (Shane et al 2003). Motives have also been investigated from the viewpoint of perceived ability in motivating persons to persevere on an entrepreneurial task (Gatewood, Shaver, Powers & Gartner 2002). Additional motivational concepts linked to entrepreneurial behaviour include, the need for independence, drive, and egoistic passion (Shane et al 2003). Research also demonstrates that there are no universal reasons leading to new business formation across gender and national boundaries (Shane, Kolvereid & Westhead 1991).

RATIONALE FOR HYPOTHESES

Based on the preceding literature and discussions, hypotheses are formulated to uncover perceptions of community support in terms of venture start-ups. Entrepreneurial behaviour was further analysed in terms of motives for start-ups.

Since the social capital literature provides rich discussion of the concept of embeddedness (Granovetter 1985), and recognizes the importance of understanding group composition in order to understand social life (Simmel 1955; Slotte-Kock & Coviello 2010), the hypotheses were formulated to highlight potential differences in community support and motives for start-ups.

Although a start-up developed by each entrepreneur is de facto unique to that individual, it is reasonable to postulate that given the socially-embedded nature of entrepreneurial activities, entrepreneurs of different communities, as designated by race and language groups, may have different community support perceptions and motives for start-ups.

Because communities reinforce some personal characteristics and penalize others, one could expect some groups to hold community support perceptions in terms of venture start-ups differently than others, particularly as these groups have largely been shaped by race in South Africa. Moreover GEM studies have consistently sampled participants according to the five major languages spoken in South Africa and also described entrepreneurial activity according to race classifications (Maas & Herrington 2007).

It is acknowledged that the term 'race' used to divide people into discrete reified social categories (Duncan 2003) could well be considered prejudicial, but in South Africa has been used in the past and even today to justify extant patterns of domination, exclusion and entitlement.

Given the anticipated differences and the exploratory nature of this study, general hypothesis were formulated which allows for more general explanations in terms of the study variables.

Hypothesis 1: Perceptions of community support and motives for start-ups will significantly differ on language groups.

Hypothesis 2: Perceptions of community support and motives for start-ups will significantly differ on race groups.

METHODOLOGY

A cross-sectional survey based study was conducted to generate responses to address the research investigation of community support perceptions on venture start-ups. Responses were solicited in a manner to allow for quantitative analysis and all items were measured with interval scales. Apart from the respondent's biographic details, the questionnaire surveyed a number of variables measuring start-up motives and community values and norms.

Sampling and data collection

Small businesses in South Africa can be classified as micro, very small, small, or medium according to a pre-determined set of thresholds. The National Small Business Act, as revised by the National Small Business Amendment Bill of 2003, breaks down the thresholds by each industry sector. South African thresholds are low by development-country norms. Many businesses regarded as SMMEs in Europe and the United States (those with fewer than 500 employees) would be defined as large enterprises in South Africa. SMME's in South Africa can only employ up to 200 people (SAIRR 2007).

Based on sampling frames provided by various agencies and chambers of commerce, 450 potential respondents were surveyed in the Johannesburg and SOWETO areas. The final sample consisting of 180 respondents included SMMEs who currently own and manage a new business, qualified as part of the sample, i.e. owning and managing a running business that has paid salaries, wages or any other payments to the owners for more than 3 months but not more than 42 months (Autio 2007). A wide range of businesses were sampled which included typical SMME sectors prevalent in these areas, for instance; agriculture, small-scale manufacturing, construction, financial, business, retail, motor trade and repair services, catering, accommodation and other trade, transport, storage and communications businesses. The trading environment was characterised by informal premises and lack of services, these included; street trader or hawker, craft market, home or friend's home, container or caravan, or local shopping centre.

Research procedure

The survey was solicited physically (dropping off questionnaires and arranging a pick-up) and electronically (sending emails, with periodic reminders). Based on eligibility criteria and suitability of respondents, 180 usable responses (an effective 49 % response rate) were generated as the final sample.

Measuring instruments

The first section of the questionnaire was concerned with the respondent's profile which included questions relating to firm level data - i.e., firm size and age, as well as biographical data - i.e., gender, age educational level, home language and race categories.

Given the focus of the study in terms of community perceptions, the participants were asked to select an in-group (a group you belong to and is part of your identify), restricted to one of the major categories provided; the same selection was used for the out-group (select which groups you do not belong to). Twelve items were used to assess, feelings, thoughts and behavioural tendencies toward the in-group and out-group, all of which were based on a pre-established instrument (Jackson 2002; Jackson & Smith 1999), which was originally designed on social identity theory which emphasizes loyalty, commitment, pride, and respect for the in-group (community).

The next section of the instrument concentrated on community influences which were measured with eleven items focusing on social norms and culture. To allow for meaningful comparisons with earlier work, a core set of questions based on the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics (PSED) survey was selected (Gartner, Shaver, Carter & Reynolds 2004). The PSED provides systematic, reliable data on those variables that explain and predict nascent entrepreneurship.

In order to understand entrepreneurial behaviour, the respondents were asked to explain their motivations for entering self-employment. Recognising the complexity of motives driving entrepreneurship, and subsequently entrepreneurial behaviour, seventeen items were used to identify salient reasons for start-ups.

Additionally, included in the biographical section, race groups were surveyed.

There appears to be a general malaise with regard to newer studies on race and racism in South Africa at present, even though race has been central to South African history for the past 350 years and is certainly pivotal to social transformation (Stevens 2003). During the apartheid era South African society were legally divided into four population groups, namely Black Africans, Whites, Coloureds and Asians or Indians (used interchangeably in this article) (Bureau of Market Research 2001). This division is still used in official statistics published by Statistics South Africa (SSA). These categories have been maintained by the post-democracy government for the purposes of promoting employment equity and equal opportunity (Carmichael & Rijamampianina 2006), and subsequently they are reported as such for the purposes of this study.

Moreover, based on the series of GEM studies, entrepreneurial activity in South Africa has been found to vary significantly by race groups (Foxcroft, Wood, Kew, Herrington & Segal 2002).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequency, arithmetic mean (IMAGEMAQUI) and standard deviation (s) and inferential statistics such as t-test, Cronbach's alpha coefficients and analysis of variance were employed to analyse the data.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

All scales were subjected to reliability analysis. Cronbach's coefficient alpha has the most utility for multi-scales at interval level of measurement, and generally a value above 0.7 is considered adequate for internal consistency (Cooper & Schindler 2001). A correlation matrix was calculated for items per scale, indicating relatively low inter-correlations between items. Cronbach's alphas for each scale were deemed satisfactory as all had values above 0.7; these values are mentioned in the notes section of the respective tables.

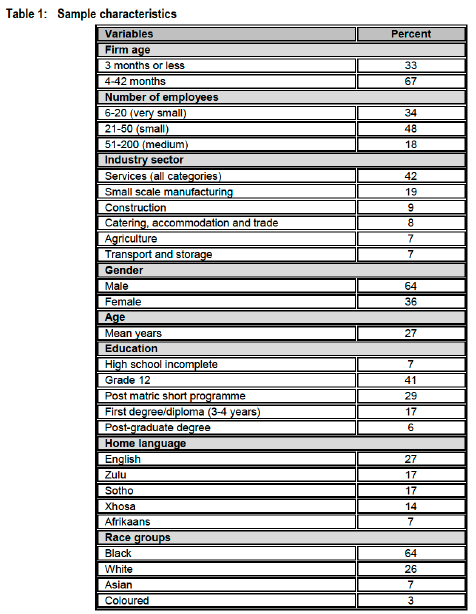

Descriptive statistics and frequency tables were calculated and the sampling characteristics results are displayed in table 1. Although table 1 is largely self-explanatory an interesting profile emerges where the entrepreneur (male), relatively young (27 years), with high-school complete, is running a small business established for more than 4 months predominantly in the services sector.

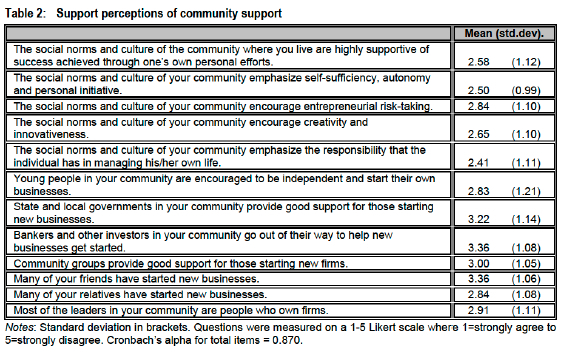

Descriptive statistics were further calculated for the various measures and the results are displayed in tables 2 and 3. In table 2, support perceptions of community resources are mostly average, i.e. midpoint on the 1-5 scale. However there is perceived disagreement (mean = 3.36) in terms of, 'bankers and other investors in your community go out of their way to help new businesses get started', and 'many of your friends have started new businesses'. Moreover by calculating and displaying the standard deviations, one can draw the conclusion that there is a relatively large amount of dispersion in the scores.

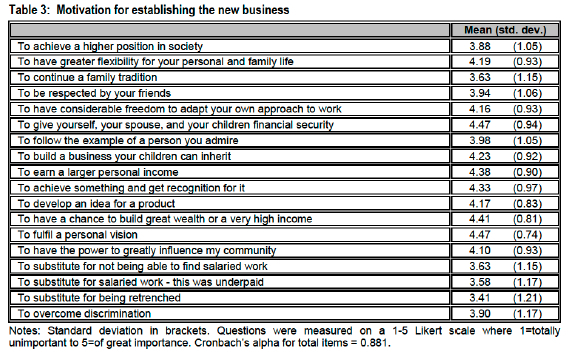

In table 3, where motivation for establishing the new business was measured, several items have higher mean scores, indicating the relative importance these variables play in motivating respondents to start a business. The highest identical mean scores (4.47) for motivations are, 'to give yourself, your spouse, and your children financial security', and 'to fulfil a personal vision'.

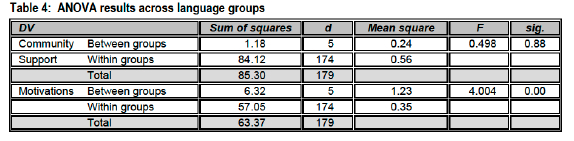

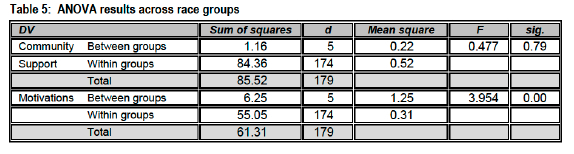

To test the study's hypothesis, comparisons between race and language groups across community resources and motivations were conducted. Initially descriptives statistics for the different language groups were calculated and compared. Based on satisfactory Levene test statistics, i.e., not significant results, used to test for homogeneity of variances, parametric tests employing analysis of variance (ANOVA) are displayed in table 4. The dependant variables (DV) are the summed items on (1) community support and (2) motivation. This table was interpreted as follows: for community support there is a 0.88 probability of obtaining an F Value of 0.498 or higher if there are no differences among group means in the population. Since this probability exceeds 0.05 one can conclude that there are no significant differences among the mean scores on this DV for the various language groups. However for the second DV - motivational items - a significant F value of 4.004 was observed (p = 0.002). To determine where the differences among the groups occur further post-hoc multiple comparison tests were calculated such as the Scheffe and Dunnett T3 tests. These tests indicated that there were no significant differences on mean scores across language groups (not shown).

The same procedure was conducted for race groups, with ANOVA, refer table 5. A significant F value of 3.954 (p = 0.031) was observed again only for the second DV -motivational items. Post-hoc multiple comparison tests indicated no further significant differences across any specific race group (not shown). Based on these indicators it seems that motivations tend to differ significantly between language and race groups.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In line with contemporary views on entrepreneurship and the importance of social embeddedness, this study examined perceptions of community support in terms of venture start-ups. The present study is one of the first to examine entrepreneurial social capital in terms of community support perceptions in South Africa. Building on previous research focusing on culture, norms and community as an instrument for investigating the creation and development of new ventures (Slotte-Kock & Coviello 2010), and given the socially-embedded nature of venture start-ups, it was expected that entrepreneurs from different race and language groups may have different perceptions of community support and motives for start-ups.

Contrary to expectations, only partial evidence for the hypothesized differences could be detected. In terms of hypothesis 1, where perceptions of community support and motives for start-ups were anticipated to differ significantly on language groups, the only significant difference was detected on motives for start-ups.

In terms of hypothesis 2, where perceptions of community support and motives for start-ups were anticipated to differ significantly differ on race groups, the only significant differences was again detected on motives for start-ups.

The finding that the only significant differences detected across race and language groups are for reasons which motivated the entrepreneurial start-ups is important since starting a business and entering into self-employment is often the first step of an entrepreneurial career (Katz 1990). Subsequently it is important to identify motives and reasons for starting a business. By focusing on various motives for start-ups, the present study has improved understanding of entrepreneurship.

Although there has been a deluge of empowerment deal making in South Africa, there is a scarcity of Blacks wanting to start and build their own businesses. The entry of Blacks into the economy has been gathering pace in the past years but has been limited by the restriction of Black entrepreneurs involved in the day-to-day running of businesses (Lediga 2006). It seems in present day South Africa, empowerment has happened at the expense of entrepreneurship, contradicting the rationale and supporting arguments of the many calls for SME development.

Policy makers could benefit from understanding that government initiatives will affect business formations only if these policies are perceived in a way that influences intentions and motives for start-ups (Krueger, Reilly & Carsrud 2000). By recognizing and building on the conceptual foundations of understanding the role of individuals in venture creation, it is imperative that policymakers take cognizance of how individual intentions make things happen through ones own actions. The entire entrepreneurial process unfolds because individual entrepreneurs act and are motivated to pursue opportunities. Being motivated is not only considered an integral aspect of empowerment but must be supplemented with education and training, since start-ups without possessing the requisite skills, knowledge and attitudes nullifies the formula for more entrepreneurship.

Research aimed at developing a better understanding of the capacities and perceptions of entrepreneurs is important in South Africa. Various key players in the South African economy share the importance of stimulating entrepreneurial social capital. Central to strategic actions initiated by the South African government, is the broadening of community support programmes and the streamlining of support institutions. These relate to the network structures facilitating, access to markets, access to finance and affordable business premises, the acquisition of skills and managerial expertise, access to appropriate technology, and access to quality business infrastructure in poor areas or poverty nodes (dti 2006).

To understand entrepreneurs and determine their drives and reasons for self-employment is critical for building knowledge in this new field where much speculation exists. Indeed community perceptions and motivations may determine the goals and aspirations of the business which in turn may determine macroeconomic outcomes.

Notes

1 * Power distance, which is related to the different solutions to the basic problem of human inequality. * Uncertainty avoidance, which is related to the level of stress in a society in the face of an unknown future. *Individualism vs. collectivism, which is related to the integration of individuals into primary groups. *Masculinity vs. femininity, which is related to the division of emotional roles between men and women. *Long term vs. short-term orientation, which is related to the choice of focus for people's efforts: the future or the present.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ADLER P.S. & KWON S.W. 2002. Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27:7-40. [ Links ]

ALDRICH H.E. & WALDINGER R. 1990. Ethnicity and entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Sociology, 16: 111-135. [ Links ]

ALDRICH H.E. & ZIMMER C. 1986. Entrepreneurship through social networks. In S. Similor & D. Sexton (Eds.). The Art and Science of Entrepreneurship. New York: Ballinger. [ Links ]

ALLEN S.A. & ORTLEPP K. 2000. The relationship between job-induced post-traumatic stress and work based social support. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 26(1):1-5. [ Links ]

AUDRETSCH D.B. & KEILBACH M. 2004. Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Regional Studies, 38:949-959. [ Links ]

AUTIO E. 2007. GEM 2007 Global Report on High-Growth Entrepreneurship. Babson College, London Business School and Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GERA). [ Links ]

BASU A. & ALTINAY E. 2002. The interaction between culture and entrepreneurship in London's immigrant businesses. International Small Business Journal, 20(4):371-393. [ Links ]

BAUMOL W.J. 1996. Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5):893-921. [ Links ]

BOSMA N. & LEVIE J. 2009. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Executive Report. Babson College, London Business School. [ Links ]

BUREAU OF MARKET RESEARCH. 2001. Research Report No 285. Pretoria: UNISA. [ Links ]

BYGRAVE W. & MINNITI M. 2000. The social dynamics of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(3):25-36. [ Links ]

CARMICHAEL T. & RIJAMAMPIANINA R. 2006. Managing Diversity in Africa. In J. Luiz (Ed.), Managing Business in Africa. Practical Management Theory for an Emerging Market: 161-187. South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

CHAN Y.E. BHARGAVA N. & STREET C.T. 2006. Having arrived: the homogeneity of high-growth small firms. Journal of Small Business Management 44(3):426-440. [ Links ]

COOPER RC. & DENNER J. 1998. Theories linking culture and psychology: universal and community specific processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 49:559-84. [ Links ]

COOPER D.R. & SCHINDLER P.S. 2001. Business research methods (7th ed.) Singapore: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

CORDER C.K. 2001. The Identification of a Multi Ethnic South African Typology. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

DAVIDSSON P. & HONIG B. 2003. The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18:301-331. [ Links ]

DAVIDSSON P. & WIKLUND J. 1997. Values, beliefs and regional variations in new firm formation rates. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18:179-199. [ Links ]

DOUGLAS E.J. & SHEPHERD D.A. 2002. Self-Employment as a career choicer: attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions and utility maximization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40:81-90. [ Links ]

DRNOVSEK M. & GLAS M. 2002. The entrepreneurial self-efficacy of nascent entrepreneurs: the case of two economies in transition. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 10(2):107-131. [ Links ]

DTI. 2006. Integrated Strategy on the Promotion of Entrepreneurship and Small Enterprises. Pretoria: Department of Trade and Industry. [ Links ]

DUNCAN N. 2003. Race talk: discourses on race and racial difference. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27:135-156. [ Links ]

EGHOSA E. & OSAGHAE O. 2005. Civil society and ethnicity in Africa. Politeia, 24(1):64-84. [ Links ]

FLORA C. & FLORA J. 1993. Entrepreneurial social infrastructure: a necessary ingredient. Annals, 529(1):48-58. [ Links ]

FOXCROFT M., WOOD E., KEW J., HERRINGTON M. & SEGAL N. 2002. GEM South African Executive Report. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, GSB. [ Links ]

GARTNER W.B., SHAVER K.G., CARTER N.M. & REYNOLDS P.D. 2004. Handbook of Entrepreneurial Dynamics: The Process of Business Creation (Eds). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

GATEWOOD E.J., SHAVER K.G., POWERS J.B. & GARTNER W.B. 2002. Entrepreneurial expectancy, task effort, and performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27:187-206. [ Links ]

GAUTENG PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT. 2008. Provincial Economic Review and Outlook 2008. Marshall Town: Gauteng Provincial Government. [ Links ]

GRANOVETTER M.S. 1973. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78:1360-1380. [ Links ]

GRANOVETTER M.S. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem with embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91:481-510. [ Links ]

GREVE A. & SALAFF J.W. 2003. Social Networks and entrepreneurship", Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Fall:1-22. [ Links ]

HOFSTEDE G. 1980. Cultures Consequences. California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

HOFSTEDE G. 2001. Cultures Consequences (2nd ed.) California: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

JACKSON J.W. 2002. Inter-Group attitudes as a function of different dimensions of group identification and perceived inter-group conflict. Self and Identity, 1(1):11-33. [ Links ]

JACKSON J.W. & SMITH E.R. 1999. Conceptualizing social identity: a new framework and evidence for the impact of different dimensions. Personality and Social Bulletin, 25:120-135. [ Links ]

KATZ J.A. 1990. Longitudinal analyses of self-employment follow through. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 2(1):15-25. [ Links ]

KILKENNY M. NALBARTE L. & BESSER T. 1999. Reciprocated community support and small town - small business success. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 11 (3):231-246. [ Links ]

KINUNDA-RUTASHOBYA L. 1999. African Entrepreneurship and Small Business Development: A Conceptual Framework. In L. Kinunda-Rutashobya & Olomi, D.R. (Eds), African Entrepreneurship and Small Business Development. Tanzania: University of Dar-Es-Salaam. [ Links ]

KRUEGER N.F., REILLY M.D. & CARSRUD A.L. 2000. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15:411-432. [ Links ]

LEDIGA C. 2006. Empowerment needs entrepreneurship too. Business Times Supplement, Sunday Times, November 19:10. [ Links ]

LUTHANS F. STAJKOVIC A.D. & IBRAYEVA E. 2000. Environmental and psychological challenges facing entrepreneurial development in transitional economies. Journal of World Business, 35:95-117. [ Links ]

MAAS G. & HERRINGTON M. 2007. GEM South African Report. Cape Town: UCT Graduate School of Business. [ Links ]

MANSFIELD G.M., FOURIE L.C.H. & GEVERS W.R. 2005. Strategic architecture as a concept towards explaining the variation in performance of networked era firms. South African Journal of Business Management, 36(4):19-31. [ Links ]

MCCLELLAND D.C. 1961. The Achieving Society. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

MCFARLIN D.B., COSTER E.A. & MOGALE C. 1999. South African management development in the twenty first century. Journal of Management Development, 18(1):63-78. [ Links ]

MCGRATH R.G., MACMILLAN I.C., AI-YUAN YANG E. & TSAI W. 1992. Does culture endure, or is it malleable? issues for entrepreneurial economic development. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(6):441-458. [ Links ]

MINNITI M. & BYGRAVE W.D. 2003. National entrepreneurship assessment United States of America. GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Babson College. [ Links ]

MOFOLO M.A. 2009. Making use of 'Batho Pele' principles to improve service delivery in municipalities. Journal of contemporary management, 6:430-440. [ Links ]

MPOFU E. 1994. Exploring the self concept in an African culture. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 155(3): 341-354. [ Links ]

MWAMWENDA T.S. 1995. Educational Psychology. An African Perspective. (2nd ed.) Durban: Butterworths. 1995. [ Links ]

NAFFZIGER D.W., HORNSBY S.J. & KURATKO D.F. 1994. Proposed research model of entrepreneurial motivation. EntrepreneurshipTheoryandPractice, 29(42):29-42. [ Links ]

PIENAAR J., SIEBERHAGEN C.F. & MOSTERT K. 2007. Investigating turnover intentions by role overload, job satisfaction and social moderation. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 33(2):62-67. [ Links ]

RIJAMAMPIANINA R. & MAXWELL T. 2002. Towards a more scientific way of studying multicultural management. South African Journal of Business Management, 33(3):17-26. [ Links ]

SAIRR. 2007. South Africa Survey 2006-2007. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations. [ Links ]

SCHUMPETER J.A. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

SHANE S., KOLVEREID L. & WESTHEAD P. 1991. An exploratory examination of the reasons leading to new firm formation across country and gender. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(6):431-446. [ Links ]

SHANE S., LOCKE E.A. & COLLINS C.J. 2003. Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2):257-279. [ Links ]

SHENKAR O. 2001. Cultural distance revisited: towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3):519-536. [ Links ]

SIMMEL G. 1955. Conflict and the web of group-affiliations. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

SLOTTE-KOCK S. & COVIELLO N. 2010. Entrepreneurship research on network processes: a review and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Jan:31-57. [ Links ]

SMITH EE & PERKS S. 2010. Evaluating SMEs corporate social performance: a stakeholder perspective. Journal of Contemporary Management, 7:71-93. [ Links ]

STANLEY L. & DAMPIER H. 2007. Cultural entrepreneurs, proto-nationalism and women's testimony writings: from the south African war to 1940. Journal of Southern African Studies, 33(3):501-519. [ Links ]

STEENSMAN K.H., MARINO L. & WEAVER M.K. 2000. Attitudes toward cooperative strategies: a cross cultural analysis of entrepreneurs. Journal of International Business Studies, 31 (4):591-610. [ Links ]

STEVENS G. 2003. Academic representations of 'race' and racism in psychology: Knowledge production, historical context and dialectics in transitional South Africa. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27:189-207. [ Links ]

THEMBA G., CHAMME M., PHAMBUKA C.A. & MAKGOSA R. 1999. Impact of macro-environmental factors on entrepreneurship development in developing countries. Eds: Kinunda- Rutashobya L., Olomi D.R. African Entrepreneurship and Small Business Development. University of Dar-Es-Salaam. [ Links ]

THOMAS A.S. & MUELLER S.L. 2000. A Case for comparative entrepreneurship: assessing the relevance of culture. Journal of International Business Studies, 31 (2):507-526. [ Links ]

THORNTON P.H. 1999. The sociology of entrepreneurship. Annual Review of Sociology, 25:19-46. [ Links ]

VON BROEMBSEN M. WOOD E. & HERRINGTON M. 2005. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, South African Report. Graduate School of Business: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

WEBER M. 1948. Essays in Sociology. Translated and edited by H.H. Gerth & C. Wright Mills. London: Routledge. [ Links ]