Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Towards an understanding of the influences on attitude towards green cosmetics in South Africa

J Beneke; N Frey; F Deuchar; A Jacobs; L Macready

School of Management Studies, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

The interest in green products and services is mounting. Recently, much attention in the political, economic and social spheres has focused on protection of the environment, sustainability and clean living. This exploratory study aims to better define what affects consumer attitudes towards green cosmetics; in particular whether the emotional aspect of green consumption drives consumers or whether they actually prefer green brands for their functional benefits. The analysis found that respondents were somewhat familiar with green cosmetics (as opposed to very familiar), but found that the perception of quality was largely on par with non-green cosmetics. Age and income were found to be differentiators with respect to product knowledge, whereas the presence of children had little effect. The affective component of the decision process was found to dominate, outweighing the cognitive component. Lastly, confusion apropos the credentials of green cosmetics was found to exist, with a significant number of respondents highlighting their inability to adequately distinguish between green and non-green cosmetic brands. The study recommends that retailers adjust their packaging to subtly, but clearly, reflect their green status and also consider an affiliation with an appropriate green initiative to reinforce this notion.

Key phrases: Green, cosmetics, personal care products, environment, attitude, consumer behaviour, affective, cognitive, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

The question relating to what drives consumers to purchase has been a long debated issue. The nuances surrounding what a consumer thinks about a product and what the consumer feels about the product has been an area of interest for marketers wishing to better position their products accordingly (Morries, Woo & Geason 2002). Dubé, Cervellon and Jingyuan (2003) concur that recently, a move towards understanding the cognitive and affective aspects of consumer buying decisions has become evident. This study aims to investigate what attracts consumers to buy green cosmetics and which aspects of attitude formation (i.e. cognitive and affective) are influential in this respect.

Moisander (2007) articulates environmentally sound products as being those which do not endanger the health of humans or animals; do not damage the environment in their creation, usage or disposal; and do not cause unnecessary waste, threaten species or environments or involve unnecessary cruelty to animals. Similarly, Mostafa (2007:220) cites Shamdasani, Chon-Lin and Richmond (1993) in defining green products as those which "do not pollute the earth or deplete natural resources, and can be recycled or conserved."

LITERATURE REVIEW

The Green Movement

Fierman (1991) states that the environment has become a persistent public issue. Fraj and Martinez (2006a) support this view, affirming that consumers will often choose green products when shopping not only for personal health reasons but also as a means to protect the environment for future generations. They proceed to explain how companies are witnessing this trend and attempting to capitalise on the green movement. D'Souza (2005) asserts that the green movement is a trend to be acknowledged, and that marketers must strive to understand green consumers and the fundamentals responsible for directing their purchasing behaviour.

This green movement has penetrated the cosmetics industry with international cosmetics companies such as Dr Hauschka and even more popular brands (such as Estée Lauder) offering purely organic, safe green product lines. Locally, companies such as The Victorian Garden have developed completely organic, animal and environmentally friendly cosmetic merchandise to meet the demand for green products in the South African market.

Green Attitudes

As the attention placed on environmental awareness heigtens and concern for the sustainability of the planet increases, it is to be expected that consumption patterns will begin to reflect these changes by way of an increase in the demand for environmentally friendly products (Tanner & Jungbluth 2003). The growth in the overall green market has, however, been less than spectacular (Hines, Hungerford & Tomera, 1987; Schultz, Oskamp & Mainieri 1995; Follows & Jobber 2000). Marketers need to understand how attitudes towards green products are formed and therefore how best to position environmentally friendly products in order to appeal to their target market (Fraj & Martinez 2006b). Yet, consumers need convincing that they are not getting a raw deal (i.e. an inferior product) whilst pledging their support for the environment. Choosing such 'new' products above trusted alternatives is therefore a risk as the layman is unaware of the outcome distributions between substitutes (Denrell 2007).

Most research in the area of attitudes has concentrated on those variables that determine attitude-behaviour consistency - namely personal values, beliefs, knowledge, personal experience and reference group influence (Fabrigar, Petty, Smith & Crites 2006). These intertwined factors are examined, in turn, below.

Beliefs

An individual's beliefs are those firmly held convictions and opinions relating to objects or situations upon which his or her knowledge is based. Azjen and Fishbein's (1977) theory of planned behaviour describes how people's actions are instigated by their behavioural intentions, which are brought about by attitudes reliant on beliefs. Thus, the green cosmetics purchaser is likely to buy environmentally friendly products based on his/her positive attitudes towards the green cause emanating from his/her beliefs in preserving the environment. Those with dogmatic beliefs will actively seek evidence that reinforces these beliefs, thereby influencing their purchasing behaviour (Davies 1998). In essence, it would appear that beliefs create purpose when selecting certain products and brands.

Personal Values

Values, similar to beliefs (Schiffman & Kanuk 2004), are composed of the principles or standards an individual chooses as a guide to behaviour and relevant actions. Karjaluoto, Mattila and Pento (2002:263) explain further how the majority of people choose to associate with persons and things that are reasonably harmonious with their personal views and identities. Schwarts and Bilsky (1987, cited by Blankenship & Wegener 2008:210) describe values as "a relative ordering of beliefs that serve as trans-situational guides for evaluative and behavioural concerns". By purchasing environmentally friendly cosmetics, the consumer exhibits value for the environment through his/her positive attitude toward green cosmetics (Fraj & Martinez 2006b). A consumer with strong values regarding the conservation of the planet is therefore likely to reflect such concerns in his/her attitudes towards consumption of green products.

Knowledge

Davenport and Prusak (1998:5) provide a comprehensive definition of knowledge as being a "flux mix of framed experiences, values, contextual information, and expert insight that provides a framework for evaluating and incorporating new experiences and information". Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995:58-59) argue that knowledge is one step beyond mere information. To this end, "information is a flow of messages, whilst knowledge is created by that very flow of information, anchored in the beliefs and commitment of its holder. A customer may have insufficient or conflicting knowledge about a particular brand, thereby initiating an information search to fill this gap, assuming the purchase is deemed of high value or importance. This may also stimulate trial.

Interestingly, some studies have concluded that environmental knowledge is not a prior condition leading to environmental purchasing action (Seligman 1985). In some instances, this condition has been found to be insufficient to ensure that relevant green purchasing activity will transpire. That said, researchers believe that further understanding this process is imperative due to the impact that increases in knowledge have on attitude and subsequent purchasing behaviour in most contexts (Fabrigar et al 2006; Holbrook, Krosnick, Berent & Visser 2005).

Personal Experience

Personal experience denotes the interaction, involvement or exposure a person has with a brand or product. In the absence of other cues, experience provides a strong sense of direction in the decision making process (Schiffman & Kanuk 2004). It is generally acknowledged amongst consumer behaviour researchers that personal experience is a major contributor to the development of attitudes and beliefs (Karjaluoto et al 2002; Fabrigar et al 2006; Glasman & Albarracin 2006). According to Rios, Martinez, Moreno and Soriano (2006), positive personal interaction with a brand or product enhances attitudes towards the brand or product. Thus, it is likely that the green cosmetics user will use personal experience, to a large extent, as cues to direct future purchasing behaviour.

Reference Group Influence

A reference group is defined by Schiffman & Kanuk (2004:330) as "any person or group that serves as a point of comparison (or reference) for an individual in forming either general or specific values, attitudes or a specific guide for behaviour". This basic concept provides a valuable perspective for interpreting the influence of some people on the functioning of other individuals. Thus, it has been proven those in a person's circle of reference whose opinions are held in high esteem, and worth due deliberation, play an evaluative role in the formation of individual attitudes (Karjaluoto et al 2002, Rydell & McConnell 2006). Social judgement theory promotes the notion that an individual's attitudes influence the attitudes of others and vice versa (Ledgerwood & Chaiken 2007). Whilst individuals may prefer to assume that their attitudes define them and therefore resist the notion that they can be easily swayed, evidence suggests that our views and notions are pliable beyond our realisation (Ledgerwood & Chaiken 2007).

Cognitive and Affective Influences on Attitude

In considering attitude toward a brand, it is necessary to consider both abstract/intangible components (such as the affective or emotional influences on attitude) as well as the more obvious influences such as product characteristics or quality. Previous theory has suggested that affect (or emotion) is less relevant than cognitive evaluation, which relates to tangible brand attributes. However, more recently, the pendulum has swung in the direction of analysing the contribution of emotional stimulation in driving consumer behaviour (Malhotra 2005).

Anand, Holbrook and Stephens (1988) support the notion that the affective component of brand evaluation has traditionally been regarded as the last and least significant step in the cognitive process of brand evaluation and attitude formation. In this respect, Aaker (1996) suggests that the reason for this might lie in the fact that cognitive motivation is easier to measure as it involves visible product attributes and tangible benefits, while also being easier for consumers to rationally motivate or explain. On the other hand, emotion or affect is not 'rational' and is less easy to understand or use as a predictor of consumption (Da Silva & Alwi 2006).

Likewise, Morries et al (2002:7) challenged this thinking and concluded that cognitive evaluation does not always dominate and that affect can directly influence brand attitude and thus determine cognitive attitude or action. Hence, they argue that "emotional response is a powerful predictor of intention and brand attitude". In a study on gender differences in impulse buying it was also found that while cognitive contemplation was involved in the purchasing decision, affect far outweighed this reasoning and, in fact, has a greater influence on the ultimate buying decision (Coley & Burgess 2003).

Jamal and Goode (2001:482-492) cite Bhat and Reddy (1998); Leigh and Gabel (1992); Levy (1959) and Mick (1986) in confirming that consumers are not always ultimately influenced by functional qualities of a brand and are thus more inclined to be influenced by the emotive symbolic qualities associated with a brand or product. It may therefore be concluded that consumers view brand symbolism and brand functionality as separate concepts (ibid).

Emotional experience with a brand is also a highly relevant factor determining brand value in the minds of consumers. Westbrook (1987) found that consumers who had a positive emotional attachment to a brand after a positive experience would be more inclined to recommend that particular brand to their peers (cited by Belén del Río, Vázquez & Iglesias 2001). Similarly, positive brand emotions will lead to a higher inclination to accept premium pricing. In trying to understand whether emotion could play a significant role in cosmetic purchasing decisions one can refer to Hirschman and Holbrook (1982) and Levy (1959) who describe consumption as being largely influenced by feelings and emotion. Further confirmation of this view is provided by Edell and Burke (1987) who verify that feelings or affect uniquely contribute to the formation of brand attitude and the determination of brand value (cited by O'Cass & Frost 2002).

Most researchers do concur that both cognitive and affective factors form the general attitude towards environmental concerns (Abdul-Muhmin 2006).With regards to the cognitive aspect, green consumers may enjoy the physical product attributes and derive immediate pleasure in knowing that the product is environmentally sound. Yet, this payoff may be dampened by the fact that the environmental benefit does not directly or solely benefit the consumer. The consumer would only derive the functional benefit of an improved environment if all consumers behaved in a similar eco-friendly manner (Hartmann, Ibáñex & Sainz 2005). This poses the "free-rider" problem or the "problem of the common" in that consumers will defect in green behaviour if they feel their contribution will make no difference, given the non-green behaviour of others (ibid).

Elliott (1997:286) reports that consumers do not simply value products for the functional, tangible or material utility they provide but rather choose to evaluate products in relation to the symbolism they evoke. If one chooses to view green cosmetics as symbols of green ideals and environmental consciousness, one could apply Elliot's theory and conclude that green consumers will evaluate green cosmetic products more for their ecologically friendly aspects than their functional brand attributes.

The personal payoff the consumer would receive from purchasing a green product would, therefore, be as a result of affect or emotion. In a survey on the attitude and behaviours of green consumers in Hong Kong, it was found that affect was far more of a mitigating factor than knowledge in determining green behaviour (Yee-Kwong & Yam 1995). Kassaye (2001:444) contends this view, declaring that consumers will defect in their green purchasing behaviour if such behaviour is at the expense of convenience. He further stipulates that the green experience has to be rewarding for consumers to persevere. This raises the question pertaining to what payoff consumers might expect to receive in 'consuming green'.

The 'impure form of altruism' (explained as an emotional payoff for doing something ethical that should require a payoff) that consumers derive from green buying often has more to do with affect and personal satisfaction than with the cognitive understanding or interest in environmental issues. Hartmann et al (2005) found that consumers who derive the most affect-based benefit from green consumption actually had low levels of environmental consciousness. This finding suggests that green consumption has become fashionable and can be used to ameliorate the self-image without the consumer being actively involved in environmental causes. Green cosmetics may provide the consumer with the ability to perceive their consumption thereof as their contribution to the green cause. This explains how green consumption involves emotional benefits based on physiological factors which, in turn, satisfy the consumer's emotional needs rather than fundamental environmental concerns (Hartmann & Ibáñez 2006).

Positioning Green Brands

Kotler & Keller (2006: 310) refer to positioning as the act of "designing the company's offering and image to occupy a distinctive place in the mind of the target market". They add that "good brand positioning helps guide marketing strategy by clarifying the brand's essence, what goals it helps the consumer achieve, and how it does so in a unique way" (ibid). Individuals will use brands to enrich their self-image and therefore will choose brands that portray images that best correlate to their self-image (Belén del Río et al 2001). "The more similar a consumer's self-image is to the brand's image, the more favourable their evaluations of that brand should be" (Graeff 1996:5). Effective brand positioning, therefore, involves aligning these self-images with effective brand images.

D'Souza (2005) affirms the need for green brands to actively publicise their support of green or environmental causes as this will help to better position products in a positive, credible manner. Ricks (2005:121) cites Keller and Aaker (1995) in affirming that a positive corporate image will directly affect how consumers perceive their products. Thus, a positive image of a green cosmetics company is likely to instil improved product trust.

Schlegelmilch, Bohlen and Diamantopoulos (1996:35) contends that green products shouldn't merely focus on green imagery, hence the need to be competitive in the market in all other aspects relating to functionality and quality. Therefore, positive green associations can be the determining factor when consumers are faced with many alternatives in a product category. Rajagopal (2006:56) argues that perceived value, as opposed to merely functional brand attributes and price, is the real driving factor in successful brand performance. Perceived value, with reference to emotional brand attachment, is determined by consumers identifying with brands in relation to their lifestyles, social values and culture, among others things. Consumers will thus be inclined to purchase green cosmetics that resonate with them.

Rajagopal (2006) confirms that advertising builds the emotional image of a brand and emotion has, according to the literature on the subject, a great influence on green purchasing behaviour. Green marketing using emotive advertisements are therefore deemed to be imperative. D'Souza (2005) cites Edell and Burke (1987) in supporting the view that feelings evoked by an advertisement will indeed have an affect on how consumers view the brand being advertised.

RESEARCH STATEMENT

The perception of green products is shaped by both functional and emotional (or moral) attributes. Previous studies have suggested that consumers are driven to purchase products that allow them to feel as though they are making a valuable contribution, or preventing harm, to the environment. However, it appears that these consumers still want these products to perform as well as their traditional counterparts. If green cosmetics are to be successfully integrated into the South African retail sector, marketers need to understand how to effectively market green cosmetics brands to ensure that consumers' needs are satisfied without removing value from their core functions. This study therefore aims to establish perceived characteristics of green products, what motivates consumers to buy them, as well as to glean insight as to the manner in which marketers can position, and differentiate, such products to good effect.

METHODOLOGY

A customer survey was implemented to investigate consumer attitudes and receptivity towards green cosmetic products. The sample consisted of consumers from all races and cultures, who were over the age of 16 years and living in South Africa. The gender divide was firmly biased towards females. The sample was intended to be predominantly female as "the men's personal care market represents only 4% of the industry" (Global Cosmetics Industry 2000 as cited in Weber & De Villebonne 2002). The fact that less than 4% of sample was male is highly consistent with the aforementioned industry statistic.

The survey was conducted in both digital and hard copy formats. The research instrument design was based on the approach taken by Guthrie, Kim and Jung (2008) wherein they explored the various factors influencing perceptions of cosmetics brands in the United State of America. The questionnaire made use of five-point Semantic Differential scales (i.e. including options for strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree) which provided a comprehensive data set to meet the objectives of this study. A pre-test was conducted to identify any problem areas and to ensure readability of the questionnaire.

RESULTS

General Perceptions

The level of familiarity with green cosmetics was initially established. In order to achieve this objective, respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the statement "I often use green cosmetics". The average response ranged from 'neutral' to 'agree', suggesting that the majority of respondents were at least somewhat familiar with green cosmetics, although not excessively so.

The question 'How would you rate your experience with environmentally friendly cosmetic products?' was posed thereafter. An average score of 3.8 (on a five-point Likert scale) was recorded, suggesting that respondents do indeed view these products favourably. When asked 'Do you believe that environmentally friendly cosmetics work as well as other cosmetics?', eight out of ten (78% of) respondents responded positively.

Demographic Influences on Product Knowledge and Beliefs

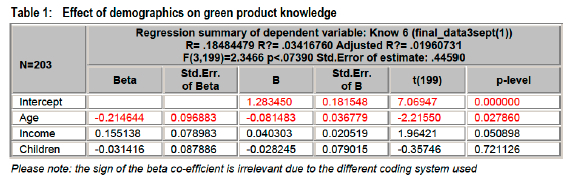

A multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine which demographic attributes had an influence on green product knowledge. Age was found to be significant at the 5% significance level (p-value of 0.028) and income was found to be significant at the 10% level (p-value of 0.051). The presence of children was not found to be a significant differentiator. In this respect, although 80% of respondents with children indicated significant knowledge, so too did 66% of those without children. The results are reflected in table 1.

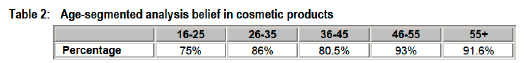

An analysis of respondents' beliefs concerning whether green cosmetics work as well as other cosmetics revealed a trend towards older age groups believing in green cosmetic efficacy to a greater degree than younger age groups. Table 2 shows the percentage of 'yes' responses to the question "Do you believe that environmentally friendly cosmetics work as well as other cosmetics?", with 90% of those aged 46 and older believing green cosmetics perform just as well as any other cosmetics.

Attitude Formation

A test was run in order to establish whether positive environmental values had a significant impact upon attitudes towards green cosmetics. The null hypothesis of no difference was rejected at the 5% significance level, as a p-value of 0.01 was recorded. Thus, the relationship was found to be highly significant. This means that the presence of green values is likely to play a fundamental role in determining attitudes towards green cosmetics. As the correlation was found to be positive, we argue that respondents with strong green values possess favourable attitudes towards green cosmetics.

The decision making process was also examined, as per figure 1.

Here, the emotional aspect of cognitive decision making was found to be a significant influencer of attitude toward green cosmetic products (p-value of 0.041). This assessment involved individuals responding to the statement "/ focused more on my personal impressions and feelings rather than on complex tradeoffs between cosmetics attributes" when purchasing green cosmetics. On the other hand, no support (even at the 10% significance level) was found to exist for the rational aspect of the decision process (i.e. the cognitive component) in playing a role in attitude formation.

'Green' Confusion

It was interesting to note that almost half of the respondents who claimed to believe that green cosmetics do not work as well as other cosmetics also claimed to have voluntarily purchased at least one of the brands mentioned in the questionnaire -especially The Body Shop, Woolworths and MAC brands. This may be due to the fact respondents were not aware that the Woolworths private label range is green or that MAC supports various green initiatives (e.g. exchanging cosmetic packaging for a free lipstick or their HIV/AIDS prevention campaign). This lack of knowledge with regards to green credentials may even be a conscious effort on the marketers' behalf so as not to bombard consumers with brand associations which may serve to interfere with pre-existing brand identity. Another reason green brands shy away from stereotypical green advertising may be due to consumers becoming wary of dubious or potentially false claims, particularly in lieu of the problem of 'green washing' (an overwhelming amount of publicity in this regard) and the lack of a reputable certification authority to authenticate green products.

CONCLUSIONS & MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

There is evidence to suggest that consumers who exhibit environmental awareness and an ethical stance in this respect are indeed more likely to possess favourable attitudes towards green cosmetic products. The onus is therefore on brand owners to strongly punt the green aspect of their particular brand and the limited negative impact such products have on environmental degradation. Taking this one step further, it may be worthwhile for green brands to associate themselves with green advocacy groups in order to build awareness and credibility in the market. In light of the fact that the emotional appeal of such brands was found to be a much stronger force than the rational appeal, relationships with charities, environmental protection agencies and health care organisations are likely to prove very valuable to brand owners. This will allow green brands to signify their allegiance with green causes and organisations by the inclusion of well known symbols of authority on their packaging. If positioned correctly, these green brands will be seen to exhibit genuine care for their cause or community and this will further heighten the philanthropic feelings held by consumers when making decisions relating to the purchase of green products.

Some level of brand confusion was detected, whereby consumers acquired specific brands but were unaware of their green credentials. This was not necessarily a shortcoming with respect to message promulgation - it would appear that some brands actually prefer not to actively promote their greenness. Dermalogica is an example of a completely green brand that consciously chooses not to publicise its green status, instead preferring to position its range of cosmetics as premium products. Likewise, brands such as The Body Shop appeal to consumers for their fresh, fruity fragrances and thus appear natural and organic' despite the fact that they may not necessarily be classified as fully green products. This adds to the confusion experienced by consumers. Indeed, it seems ironic that brands which do not appear green (such as cosmetics under the Woolworths and MAC labels) are, in reality, greener than brands such as The Body Shop which publicise their 'natural' aspect.

The research suggests that despite age being positively correlated with the belief that green cosmetics are just as effective as their non-green counterparts, this may not necessarily translate into a decision to purchase. Habitual buying behaviour poses a barrier to adoption in this respect, whereby some consumers are less inclined to switch from their usual cosmetic brand to greener brands. This is likely to be particularly prevalent amongst older consumers who are conservative and resistant to change, despite their environmental concerns. Here, an opportunity exists to appeal to the young professional market in order to shift their ideology and stimulate their buying behaviour. Perhaps marketing communications should be adapted to communicate with a younger audience, using appropriate mass media and social networking channels. Furthermore, marketers should reassess the green brand imagery on offer, possibly giving it a makeover to reflect a more contemporary look and feel.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AAKER D.A. 1996. Building Strong Brands. London: Simon & Schuster UK Ltd. [ Links ]

AJZEN I. & FISHBEIN M. 1977. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5):888-918. [ Links ]

ABDUL-MUHMIN A. 2006. Explaining consumers' willingness to be environmentally friendly. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31 (3):237-247. [ Links ]

ANAND P., HOLBROOK M. & STEPHENS D. 1988. The formation of affective judgments: the cognitive-affective model versus the independence hypothesis. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(3):386-381. [ Links ]

BELÉN DEL RÍO A., VÁZQUEZ R. & IGLESIAS V. 2001. The effects of brand associations on consumer response. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18 (5):410-425. [ Links ]

BHAT S, & REDDY S.K. 1998. Symbolic and functional positioning of brands. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 15(1):32-43. In: Jamal A. & Goode M.M.H. (2001). Consumers and brands: a study of the impact of self-image congruence on brand preference and satisfaction. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19(7):482-492. [ Links ]

BLANKENSHIP K. & WEGENER D. 2008 Opening the Mind to Close It: Considering a Message in Light of Important Values Increases Message Processing and Later Resistance to Change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2):196-213. [ Links ]

COLEY A. & BURGESS B. 2003. Gender differences in cognitive and affective impulse buying. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 7(3):282-295. [ Links ]

D'SOUZA C. 2005. Green advertising effects on attitude and choice of advertising themes. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 17(3):51-66. [ Links ]

DA SILVA R. & ALWI S. 2006. Cognitive, affective attributes and conative behavioural responses in retail corporate branding. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 15(5):293-305. [ Links ]

DAVENPORT T. & PRUSAK L. 1998. Working knowledge: Managing what your organization knows. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

DAVIES M. 1998. Dogmatism and Belief Formation: Output Interference in the Processing of Supporting and Contradictory Cognitions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2):456-466. [ Links ]

DENRELL J. 2007. Adaptive Learning and Risk Taking. Psychological Review, 14(1):177-187. [ Links ]

DUBÉ L., CERVELLON M-C. & JINGYUAN H. 2003. Should consumer attributes be reduced to their affective and cognitive bases? International Journal of Marketing in Research, 20(3):259-272. [ Links ]

EDELL J. & BURKE M. 1987. The power of feelings in understanding advertising effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 14:421-433. In: O'Cass A. & Frost H. (2002). Status brands: examining the effects of non-product-related brand associations on status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 11(2):67-88. [ Links ]

ELLIOTT R. 1997. Existential consumption and irrational desire. European Journal of Marketing, 31 (3/4):285-96. In: Jamal A. & Goode M.M.H. (2001). Consumers and brands: a study of the impact of self-image congruence on brand preference and satisfaction. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19(7):482-492. [ Links ]

FABRIGAR L., PETTY R., SMITH S. & CRITES S. 2006. Understanding Knowledge Effects on Attitude-Behavior Consistency: The Role of Relevance, Complexity, and Amount of Knowledge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(4):556-577. [ Links ]

FIERMAN J. 1991. The big muddle in green marketing. Fortune, 3 June:91-101. [ Links ]

FOLLOWS S. & JOBBER D. 2000. Environmentally responsible purchase behaviour: a test of a consumer model. European Journal ofMarketing, 34(5/6):723-746. [ Links ]

FRAJ E. & MARTINEZ E. 2006a. Ecological consumer behaviour: an empirical analysis. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31 (1):26-33. [ Links ]

FRAJ E. & MARTINEZ E. 2006b. Environmental values and lifestyles as determining factors of ecological consumer behaviour: an empirical analysis. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(3):133-144. [ Links ]

GLASMAN L. & ALBARRACIN D. 2006. Forming Attitudes That Predict Future Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis of the Attitude-Behaviour Relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5):778-822. [ Links ]

GLOBAL COSMETICS INDUSTRY. 2000. "Men's Personal Market", January. In: Weber J.M. & De Villebonne J.C. (2002). Differences in purchase behaviour between France and the USA: the cosmetic industry. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 6(4):396-407. [ Links ]

GRAEFF T.R. 1996. Using promotional messages to manage the effects of brand and self-image on brand evaluations. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13(3):4-18. [ Links ]

GUTHRIE M., KIM H. & JUNG J. 2008. The effects of facial image and cosmetic usage on perceptions of brand personality. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 12(2):164-181. [ Links ]

HARTMANN P. & IBÁÑEZ V.A. 2006. Green Value Added. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 24(7):673-680. [ Links ]

HARTMANN P., IBÁÑEZ V.A. & SAINZ F.J. 2005. Green branding effects on attitude: functional versus emotional positioning strategies. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 23(1):9-29. [ Links ]

HINES J., HUNGERFORD H. & TOMERA A. 1987. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Education,18(2):1-8. [ Links ]

HIRSCHMAN E.C. & HOLBROOK M.B. 1982. Hedonic consumption: emerging concepts, methods and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46:92-101. In: O'Cass, A. and Frost, H. (2002). Status brands: examining the effects of non-product-related brand associations on status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 11(2):67-88. [ Links ]

HOLBROOK L., KROSNICK J., BERENT M. & VISSER P. 2005. Attitude Importance and the Accumulation of Attitude-Relevant Knowledge in Memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(5):749-769. [ Links ]

JAMAL A. & GOODE M.M.H. 2001. Consumers and brands: a study of the impact of self-image congruence on brand preference and satisfaction. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19(7):482-492. [ Links ]

KARJALUOTO H., MATTILA M. & PENTO T. 2002. Factors underlying attitude formation towards online banking in Finland. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 20(6):261-272. [ Links ]

KASSAYE W. W. 2001. Green Dilemma. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19(6):444-455. [ Links ]

KELLER K. & AAKER D. 1995. Managing the corporate brand: the effects of corporate images and corporate brand extensions. Stanford University Graduate School of Business, Research Paper No. 1216. [ Links ]

KOTLER P. & KELLER K. 2006. Marketing Management, 12th edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

LEDGERWOOD A. & CHAIKEN S. 2007. Priming us and them: Automatic assimilation and contrast in group attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6):940-956. [ Links ]

LEIGH J.H & GABEL T.G 1992. Symbolic interactionism: its effects on consumer behaviour and implications for marketing strategy. The Journal of Services Marketing, 6(3):5-16. In: Jamal A. & Goode M.M.H. (2001). Consumers and brands: a study of the impact of self-image congruence on brand preference and satisfaction. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19(7):482-492. [ Links ]

LEVY S.J. 1959. Symbols for sale. Harvard Business Review, 37(4):117-124. In: O'Cass A. & Frost H. (2002). Status brands: examining the effects of non-product-related brand associations on status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 11 (2):67-88. [ Links ]

MALHOTRA N. 2005. Attitude and affect: new frontiers of research in the 21st century. Journal of Business Research, 58(4):477-482. [ Links ]

MICK D.G. 1986. Consumer research and semiotics: exploring the morphology of signs, symbols, and significance. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(2):196-213. In: Jamal A. & Goode M.M.H. (2001). Consumers and brands: a study of the impact of self-image congruence on brand preference and satisfaction. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19(7):482-492. [ Links ]

MOISANDER J. 2007. Motivational complexity of green consumerism. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(4):404-409. [ Links ]

MORRIES J., WOO C. & GEASON J. 2002. The power of affect: predicting intention. Journal of Advertising Research, 42(3), 7-17. [ Links ]

MOSTAFA M.M. 2007. Gender differences in Egyptian consumers' green purchase behaviour: the effects of environmental knowledge, concern and attitude. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31 (3):220-229. [ Links ]

NONAKA I. & TAKEUCHI H. 1995. The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

O'CASS A. & FROST H. 2002. Status brands: examining the effects of non-product-related brand associations on status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 11 (2):67-88. [ Links ]

RAJAGOPAL. 2006. Brand excellence: measuring the impact of advertising and brand personality on buying decisions. Measuring Business Excellence, 10(3):56-65. [ Links ]

RICKS J.M. 2005. An assessment of strategic corporate philanthropy on perceptions of brand equity variables. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(3):121-134. [ Links ]

RIOS F., MARTINEZ T., MORENO F. & SORIANO P. 2006. Improving attitudes toward brands with environmental associations: an experimental approach. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23(1):26-33. [ Links ]

RYDELL R. & MCCONNELL A. 2006. Understanding Implicit and Explicit Attitude Change: A Systems of Reasoning Analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91 (6):995-1008. [ Links ]

SCHIFFMAN L. & KANUK L. 2004. Consumer Behavior, 8th edition. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

SCHLEGELMILCH B., BOHLEN G.M. & DIAMANTOPOULOS A. 1996. The link between green purchasing decisions and measures of environmental consciousness. European Journal of Marketing, 30(5):35-55. [ Links ]

SCHULTZ W., OSKAMP S. & MAINIERI T. 1995. Who recycles and when? A review of personal and situational factors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(2):105-121. [ Links ]

SELIGMAN C. 1985. Information and energy conservation. Marriage and Family Review, 9(1&2):135-149. [ Links ]

SHAMDASANI P., CHON-LIN G. & RICHMOND D. 1993. Exploring green consumers in an oriental culture: role of personal and marketing mix. Advances in Consumer Research, 20:488-493. [ Links ]

TANNER C & JUNGBLUTH N. 2003. Evidence for the Coincidence Effect in Environment Judgements: Why Isn't It Easy to Correctly Identify Environmentally Friendly Food Products? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 9(1):3-11. [ Links ]

WESTBROOK R.A. 1987. Product/consumption-based affective responses and post-purchase processes. Journal of Marketing Research, 24:258-270. In: Belén del Río A., Vázquez R. & Iglesias V. (2001). The effects of brand associations on consumer response. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(5):410-425. [ Links ]

YEE-KWONG CHAN R. & YAM E. 1995. Green movement in a newly industrialized area: A survey on the attitudes and behaviour of the Hong Kong Citizens. Journal of Community & Applied Psychology. 5(4):273-284. [ Links ]