Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The formulation and implementation of a servitization strategy: factors that aught to be taken into consideration

S Benade; RV Weeks

Graduate School of Technology Management, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

The concept "servitization" has its genesis in a paper by Vandermerwe and Rada (1983:315). It is suggested that it is a concept that has increasing relevance with the emergence of the global services economy (Weeks 2008:40; Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons 2008:3). Increasingly manufacturing institutions are adding layers of services to existing manufacturing systems, without due consideration to the strategic and operational consequences thereof. It is suggested that consideration aught to be given to developing a servitization strategy in responding to a services dominant global economy. Factors that need to be considered in the formulation and implementation of a servitization strategy are analysed on the basis of a multidisciplinary literature research study and the key findings and insights gained constitute the focus of this paper.

Key phrases: Business models, nature of services, transdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary collaboration, services culture, servitization, strategy

INTRODUCTION

"Management literature is almost unanimous in suggesting to product manufacturers to integrate services into their core product offerings"

Rogelio Oliva and Robert Kallenberg (2003:160)

The introductory quotation attests to the growing importance attributed to servitization within the literature, but it would appear that just how this is to be achieved in practice remains less certain. Wilson (2008:9) in a similar sense appear to echo Oliva and Kallenberg's (2003:160) assertion in suggesting that "manufacturing and technology industries such as cars, computers and software are also recognizing the need to provide quality service and revenue-producing services in order to compete world wide". It is therefore hardly surprising to find that the World Economic Forum's (World Economic Forum 2009:55) global competitive index for 2009-2010 reveals that just over 70% of the 133 nations listed have a services sector gross domestic product (GDP) in excess of 50%. In the case of South Africa services represents 66% of the country's total GDP (World Economic Forum 2009:55). The emergence of services as the dominant sector of the global economy and in many cases national economies underscores the importance that aught to be attributed to servitization (Weeks & Benade 2009:390). Most developing nations, such as South Africa, in fact need to be able to effectively compete in the global services economy for a greater share of the action, as their national economies are just too small for sustainable growth. With this in mind it is interesting to note that, Vargo and Lusch (2008:254) claim that logic of the need for a shift in the strategy and activities of an enterprise, to match the analogous shift in the economy, is intuitively so compelling that it could well be assumed to be an apparent truism. While they agree that a shift to a service focus is desirable, if not essential to a firm's well being, Vargo and Lusch (2008:254) go on to question the underlying rationale and the associated implied approach, by suggesting that a service-centric logic not only amplifies the necessity for the development of a service focus, but also provides a stronger foundation for theory development and, consequently, application.

Service are inherently very different from products in terms of their very nature (Desmet, Van Looy & Van Dierdonck 2003:11; Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons 2008:17) and merely adding layers of services to products, so as to increase an institution's revenue generating capability or improve its competitive position in the marketplace, is hardly an appropriate solution (An, Lee & Park 2008:621; Weeks & Benade 2009:393; Wilson 2008:15). Manufacturing systems (products) are for instance transaction oriented, while services are relationship driven, which by implication implies two very fundamentally different underlying management systems and ways of conducting business. The business models and their underpinning logic are indeed very different, so much so, that it is suggested in this paper that a very well though through and debated strategy is required for informing and directing the servitization process. The traditional logic underpinning a manufacturing strategy is one of obtaining increasing efficiencies and associated cost reduction, while improving the quality of the product (Voss 2005:1212). In contrast the very notion of quality from a services perspective is complicated by the fact that it is intangible in nature, difficult to define and embodies a very definite relationship element (Desmet et al 2003:12; Fitzsimmons & Fitzimmons 2008:20,41). Voss (2005:1214) very pertinently states that the content of manufacturing strategy has traditionally been viewed as strategic choices in process and infrastructure with an accent on adopting so called best practice.

Closely aligned to the concept of "best practise", according to Voss (205:1212,1216), is the notion of being "world class", which the researcher defines as "having best practice in total quality, concurrent engineering, lean production, manufacturing systems, logistics and organization and practice". Accentuated by its very absence is any reference to services that clients may require in relation to products that have been acquired. This apparent lack of reference to services as a means to gain greater market share in the formulation of the traditional manufacturing institution's strategy appears to be quite prevalent from a historical perspective. Schmenner (2009:431) for instance suggests that "from the advent of the industrial revolution through the latter portion of the nineteenth century, almost all manufacturing companies simply engaged in manufacturing, they did not also provide bundled services and they did not control their supply chains through vertical integration".

Within a service driven economy the omission to focus on complementary services associated with the products manufactured, in developing the institution's strategy, could quite evidently have very significant implications for an institution attempting to gain a competitive advantage in a marketplace that is services dominant. Schmenner (2009:431) claims that it is only in the last two decades that the term "servitization" was coined to capture the innovative services that have been bundled (integrated) with goods by firms that had previously been known strictly as manufacturers, thereby initiating a change in traditional manufacturing management thinking and strategy.

Voss (2005:1212) would seem to concur with Schmenner (2009:431) that at it is simplest the traditional approach to manufacturing strategy argues that the firm should compete through its manufacturing capabilities, and should align its capabilities with the key success factors, its corporate and marketing strategies and the demands of the marketplace. What is of pertinence in this statement, however, is the reference to demands of the market place, as changes in the marketplace are most probably one of the most important driving forces that have given rise to the evolution of the concept "servitization". From within a more contemporary perspective, Spring and Araujo (2009:444) observe the respective roles of products and services in delivering benefits to customers have become an increasingly closely studied issue. And of even more pertinence and relevance, Spring and Araujo (2009:444) citing a number of researchers, stress that there has been a resurgence of interest in the foundations of services per se, influenced by the changing practices in erstwhile manufacturing firms and the promotion of "services science" by IBM.

An important thread winding its way through this discussion is the need for manufacturing and engineering enterprises to integrate services into what could be termed a bundle of products and services for clients, so as to gain a competitive advantage in the marketplace and increase the revenue base. Adding layers of services to products it would certainly appear is fraught with difficulty and risk and it would appear that an integrated manufacturing and services strategy is required (An et al 2008:622; Spring & Araujo 2009:453).

Seen within the context of the introductory discussion, in the ensuing sections the differences between manufacturing (products) and services are briefly analysed with reference to the implications thereof in terms of strategy development and implementation. Thereafter specific aspects to be considered in the formulation of a servitization strategy are dealt with and the key insights and findings from the research study are briefly summarised.

NUANCE DIFFERENCES IN MANUFACTURING (PRODUCTS) AND SERVICES: A STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVE

Spring and Araujo (2009:445) draw attention to an interesting emergent trend whereby clients instead of purchasing a product, such as a car, television set, computer, or even for that matter hardcopy journals or music CDs, actually purchase the use thereof via a service provided to clients by institutions. Actual ownership is not transferred and in addition a number of add on services such as upgrading, repairs and maintenance are often included in the service contract and cost (Weeks & Benade 2009:398). The boundary lines between the purchasing of a product or a service it would appear is therefore becoming rather fuzzy or blurred in some cases and consequently rather more difficult to define. Kumar and Markeset's (2007:272) research revealed that oil and gas producers in the North Sea increasingly require the use of complex technology to prolong the economic lifetime of tail-end production facilities. Technology that also requires highly skilled operational and maintenance personnel and there apparently is an increasing trend for oil and gas producers to make use of external institutions to provide them with a complete business solution (Kumar & Markeset 2007:272). An et al (2007:622), citing Sundin, refer to this as an "integrated product and services offering" directed at meeting specific client needs. They go on to advocate technology "roadmaping", as one of the most useful and widely used methods, for strategic management of product or service development (An et al 2007:622). They also assert that most research studies have focused on product or services roadmaps, with little attention being paid to their integration. Available technology roadmaps that include products and services apparently, according to An et al (2007:622), do not properly reflect the characteristics of product-service or clearly suggest how to integrate them. The integration process it would seem is difficult and entails interdisciplinary research challenges (An et al 2007:622).

As suggested by means of this brief narrative account, the inherent nuance differences that exist between products and services acts as a constraint in their integration and in defining the integrated offering or business solution presented to clients. Of particular significance, however, is the fact that the examples used reflect a very fundamental shift in strategic thinking, as to what the client in fact is purchasing and what institutions in fact are offering to clients. It is a dilemma that from a strategic management perspective, has very definite implications, as a wide range of product and service permutations exists and at the heart of any strategy is a quest for gaining a sustainable competitive advantage (Hough, Thompson, Strickland & Gamble 2008:5).

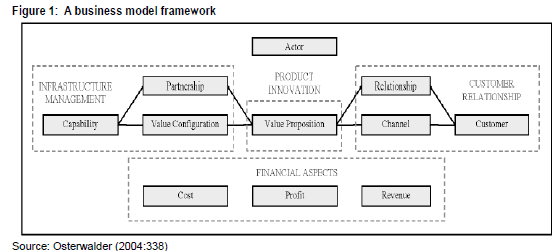

The term "offering", according to Saara Brax (2005:143), is used to denote any physical good, service, information, or any combination of these that a company can offer to its customers; the total offering thus includes all offerings of a company as an aggregate. It would therefore seem to incorporate both tangible product and intangible services related components. The services and manufacturing related businesses components it would seem therefore have significant differences that originate from the perishable, complex and multifunctional nature of services and service activities (Brax 2005:142; Desmet et al 2003:16; Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons 2008:19-20). The distinctive differences between the product and services related components of the business offering, or what Osterwalder (204:338) terms to be the value proposition offered to clients, assumes a very definite strategic focus, as it forms a core consideration in the development of an institution's business model, as depicted in figure 1 below. Weeks and Benade (2009:395), citing Magretta, claim "the strength of adopting a business model approach in planning and managing the servitization process is that it focuses attention on how all the elements of the system fit into a working whole". This by implication would seem to suggest a very definite consideration of the intricacies associated with integrating both the tangible and intangible elements of the value proposition. This is quite acutely demonstrated in terms of having to shift from a product orientation (transaction) to a process of "value creation" and even more specifically within the services context if seen in terms of the role played by clients in the service encounter (Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons 2008:175-177; 20]. The integrated product service system (PSS) is deemed make available an offering or value proposition that delivers value to a specific client and to succeed with such a servitization strategy, a manufacturer will require new guiding principles, which are likely to be rather different to those traditionally associated with a manufacturing strategy (Baines et al 2009:495; Oliva & Kallenberg 2003:161).

The business model framework in effect visually describes the "value proposition" the institution offers to clients with the objective of generating profitable and sustainable value streams for the institution itself, while taking the infrastructure required therefore into consideration, as well as the relationship networks that need to be established (Weeks & Benade 2009:395). Yet other researchers suggest making use of what is termed to be a services blueprinting framework for differentiating between the less tangible front-end, or customer related interactions, and the more tangible backend systems and operational support components (Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons 2008:71-73; Shostack 1984:133-134; Fließ & Kleinaltenkamp 2004:396; Tax & Stuart 1997:106; Wilson 2008:198). Fließ and Kleinaltenkamp (2004:393) more specifically view blueprinting as a heuristic method for analyzing and designing service processes, as such it constitutes a picture or map that accurately portrays the service system. In effect therefore services blueprinting may be summarised as constituting a description of all the activities pertinent to designing and managing services. Clearly these are all very significant aspects to be considered in the formulation and implementation of an institution's servitization strategy, yet it is suggested by Alam (2006:468) there is a dearth of empirical research in relation to both customer interaction and front-end stages of services innovation, despite the importance attributed thereto. The relatively narrow focus on the tangible product elements, according to Alam (2006:469), has essentially failed to take account of the intricacies associated with services innovation and it is apparently frequently assumed that the development processes for tangible products and services are similar in nature. This while they tend to be differentiated in character by intangibility, perishability, simultaneity, and customer participation (Alam 2006:469; Fritzimmons & Fritzimmons 2008:19-20;). It is argued that these distinguishing characteristics need to be taken into consideration in formulating and implementing the servitization strategy.

Customer involvement

Gummesson (2002:586) makes a very definite statement that "in services, customer-supplier interaction and relationships in the services encounter stands out as the most distinctive feature separating them from goods" Research conducted by Baines et al (2009:502) also found that notably absent from manufacturing strategic frameworks is the accent on customer relations, yet direct and indirect customer participation forms an inherent characteristic of a services orientated strategy and operational system. This omission, it is claimed by Baines et al (2009:502), is indicative of the internally centred focus of manufacturing, which is endemic within the industry, and reflects traditional strategic management thinking.

The notion of customer involvement, as a differentiating characteristic between traditional manufacturing and services, is also very pertinently addressed by Fritzsimmons and Fritzsimmons (2008:18) in suggesting that client participation in the services process introduces a number on factors that aught to be given consideration, which would not necessary be the case within a traditional manufacturing operations management context. A case in point cited by the researchers is the attention that needs to be given to facility design (Fritzsimmons and Fritzsimmons 2008:18). The client's presence on-site and the services encounter itself implies that the physical location and facility aspects such as ambiance, aesthetics, security, safety, capacity, self-service and queuing configurations all need to be taken into consideration (Fritzsimmons & Fritzsimmons 2008:200). It could be argued that manufacturing institutions would hardly be inclined to value the client's involvement in the manufacturing process, which tends to be standardised to achieve economies of scale (Fry, Steele & Saladin 1994:18). The selection of the location for building factories would also hardly traditionally be based on ease of access for clients, but in formulating the servitization strategy it would constitute a backend component that needs to be integrated with a front-end or as termed by Teboul (2006:19) "front stage" component that is client focused and orientated (Fließ & Kleinaltenkamp 2004:396; Teboul 2006:24).

The distinctive differentiating trend between manufacturing and services and the accent place on client involvement is also insinuated by Baines et al (2007:1549), who stress that "a successful PSS needs to be designed at the systemic level from a client perspective and requires early involvement with the customer and changes in the organizational structures of the provider'. Involving clients in the formulation of an integrated product services strategy would, from a traditional manufacturing management perspective, seem to imply and require a very fundamental reorientation in manufacturing strategic thinking. Kindström and Kowalkowski (2009:157) acknowledge that a product/manufacturing culture and mindset is likely to be a constant challenge in embarking on a servitization strategy. They very pertinently claim that "manufacturing companies have typically exhibited a product and technology orientation and many of them are relatively new to a service logic and to service innovation." (Kindström & Kowalkowski 2009:157). New service development, it is suggested, is deemed to be complex, difficult to define and intricate to articulate, resulting in its unique aspects not always being traditionally taken into consideration (Kindström & Kowalkowski 2009:157). A case in point cited being client involvement in both the design and implementation of the services concerned (Kindström & Kowalkowski 2009:161-162). Kindström and Kowalkowski (2009:158) very pertinently stress that the client is no longer regarded as a passive "transaction-oriented actor', but rather as an active "relationship-oriented actor' dynamically involved in the co development and implementation involvement of the services strategy. Vargo and Lusch (2008:256) similarly accentuate the importance of relationships with clients as an important consideration that needs to be taken into account. One of the disguising features of the servitization strategy, according to Kindström and Kowalkowski (2009:158), is the client interaction that takes place in developing services offerings, consequently placing an emphasis on the need for developing strong relationships with the institution's client base. This reality inherently makes the servitization process and the underpinning strategy far more complex to deal with than the traditional manufacturing strategy.

From the preceding discussion it can be inferred that a key distinguishing factor between a traditional manufacturing strategy and a services strategy would appear to be the accent placed on client relationships, involvement and interaction. Baines, Lightfoot, Benedettini and Kay (2009:559) more specifically suggest that the accent generally is one of organisations providing "solutions through product-service combinations", which "tend to be client-centric". The researchers also claim that case studies highlight the importance of client partnering and the need for expanded competences in providing integrated solutions (Baines et al 2009:559). It is also pointed out by the researchers, however, that service management principles are often at odds with traditional manufacturing practices and that a definite shift of corporate mindset is deemed necessary to take on services, namely one of abandoning product-centric thinking in order to become more customer-centric (Baines et al 2009:559). Integrating the client into the strategic solution, however, brings with it very definite challenges, such as that associated with client-induced variability of service quality and management of capacity and demand. Fitzsimmons and Fitzsimmons (2008:18-19,77-78,258) point out that different levels of client knowledge, physical abilities and skills creates capacity variability that have a direct impact both on service quality and the time taken to complete service delivery. Increasing client participation and involvement does, however, have its positive spin-offs as illustrated by increased client participation eliminating the need for institutional staff to perform the activities concerned (Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons 2008:19). This has definite cost benefits for both the institution and the client. These are all certainly strategic considerations that manufacturing institutions would not have traditionally been confronted with, yet in formulating the servitization strategy they come to the fore as very definite aspects to be considered.

Client involvement in the design and implementation of an integrated manufacturing and services strategy certainly implies a fundamental change in the way manufacturing institutions function, both at a strategic and operational level. This in turn will have implications in terms of the culture of the institution. Mathieu (2001:464) is a researcher who would seem to concur with this assumption, in stating that "a service culture is specific and different from the traditional manufacturing culture". The systemic changes required in managing the servitization process are generally relatively straightforward to introduce, but the difficulty so often encountered relates to the changing of the underpinning philosophy of how services centric business operations are conducted (Pfeffer 2005:124; Weeks & Benade 2009:393). With this in mind it is not difficult to see why Baines et al (2007:1549) specifically declare that servitization entails a cultural shift with an associated inherent mindset change that breaks down the "business as usual attitude" that prevails within the institution. The incorporation of the client in the strategy development and implementation process certainly constitutes a break with the "business as usual" paradigm of thinking and consequently has organisational culture implications. Notably, Seel (2000:2) defines culture as: "the emergent result of the continuing negotiations about values, meanings and proprieties between the members of that organisation and with its environment" and inherently such negotiations and debate can be expected to emerge from the servitization process, as staff and management come to grips with the new reality and role of client involvement in the activities of the institution. Magnusson and Stratton (2000:53) in researching the servitization process conclude that "a direct derivative of people is relationships and, as intangible assets, they denote yet another layer in the service culture atmosphere".

Intangibility of services

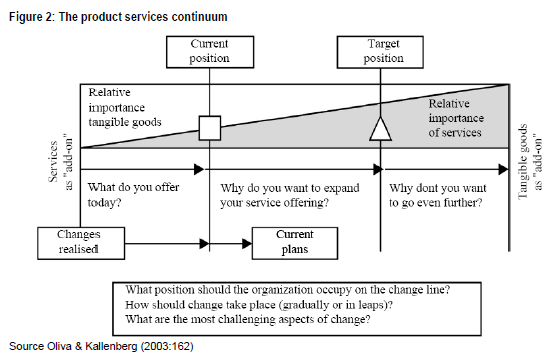

A general differentiation between products and services, according to Magnusson and Stratton (2000:14-15), is the view that goods are tangibly produced, while services are intangibly performed. Brax (2005:143), as well as Oliva and Kallenberg (2003:162) place services and manufactured products on two ends of a scale with products termed to be tangible and services intangible. The researchers make use of a graphic presentation of the continuum, which is depicted in figure 2, to explore the evolution of the services and products as an "add-on" with goods being prefixed as tangible (Oliva & Kallenberg 2003:162). The insinuation is one of the relative importance of services as an intangible element gaining in relevance over time. The bundle of products and services offered therefore assume a mixture of tangible and intangible elements depending on the composition thereof.

The tangible nature of products and the intangible nature of services are used to define the concept "services" by Baines et al (2009:554), namely "services are an economic activity that does not result in ownership of a tangible asset'. Following the same pattern of thought as Magnusson and Stratton (2000:14-15), it is argued by Baines et al (2009:554) that "services are performed and not produced and are essentially intangible". As is the case with Magnusson and Stratton (2000:14-15) they also make use of a product-service continuum to differentiate between various forms of servitization (2009:557). The phased introduction of added intangible services in order to achieve successful implementation of a service strategy in manufacturing companies is seen to provide a safer journey for companies along the road to servitization (Baines et al 2009:561). Insinuated therefore is that the intangibility of services constitutes a difficulty in managing the servitization process, one best dealt with by gradually increasing the intangible services component to the bundle of products and services offered to clients. Brax (2003:152), however, observes a paradox here, in that services introduced in this way can be perceived as being secondary to the tangible product and hence may lack cross-functional support, leading to failures in service operations.

Citing a number of leading management researchers and thought leaders, Baines et al (2009:561) propose "de-centralised customer facing service units with profit and loss responsibility within the organisation as a key factor in a successful service strategy ". Research conducted by Weeks and Benade (2009:400) similarly revealed a need for the establishment of a separate services unit in implementing a servitization strategy. Running the product-service business separately mitigates the risk associated with the intangible nature of services (Baines et al 2009:561). Clearly, the intangible characteristic of services would appear to have a far ranging implication in the formulation and implementation of a servitization strategy.

Fritzsimmons and Fritzsimmons (2008:20) make the observation that services as an intangible, innovative construct of ideas, insights and concepts are not all that easily patentable, which stand in stark contrast to product innovations that generally can be patented. It is therefore quite easy for competitors to replicate a similar innovative service offered to clients. Gaining a competitive advantage through service differentiation is difficult to achieve and organisational culture may be the only inhibiting factor for competitors in some cases, as replicating a specific services culture is not only extremely difficult, but near impossible in practice as it exhibits emergent properties of a complex system (Weeks & Benade 2009:399). A strategy of obtaining market leadership through innovation of new services and state of the art technology application therefore implies a never ending process of never ending renewal to stay ahead of the competition, again implying the need for a very flexible and adaptive culture.

When it comes to developing the marketing strategy, as a distinct component or element of the servitization strategy, the intangibility of services surfaces as a significant constraint that needs to be addressed (De Pelsmacker & Van den Berg 2003:74; Gilmore 2003:18-19; Grove, Carlson & Dorsch 2002:394). At the core of the problem, according to Pelsmacker and Van Den Berg (2003:74), as well as Gilmore (2003:10), is the difficulty clients experience in attempting to evaluate services before consuming them during the services encounter. In a sense institutions are attempting to sell "vapour ware" in marketing a service that does not exist before it is experienced. Typical cases in point are legal, engineering or management consulting, as well as medical, and dental services offered to clients. As noted by Pelsmacker and Van Den Berg (2003:74) clients in an attempt to make sense of the situation tend to identify and observe the tangible elements associated with a service in search for clues as to service quality. Offering clients a bundle of tangible products and intangible services would seem to suggest the product quality could by implication have an impact on clients' perception of potential services that could be rendered in relation to the products. The reverse is also, however, true. Negative narrative accounts or stories of poor services can negatively impact on clients' perception of tangible products.

Pelsmacker & Van Den Berg (2003:74) specifically daw attention to the tendency of clients to acquire information via the experiences of others and without doubt this is a very significant trend that needs to be monitored in the implementation of the servitization strategy. Ostensibly, such an effort can assist clients to generate mental representations of a services lacking physical reality. Communicating the intangible benefits associated with a service is complicated by the inherent risks associated with the service experience, as once enacted the service cannot be undone and this may well have very fundamental consequences for clients.

Grove et al (2002:394) in researching the communication challenge associated with communicating the intangible characteristics of services to a target audience, found that adding tangibility by conveying factual information, evoking visualisations or establishing associations with physical elements, can be a means used to assist clients in gaining a perception of the intangible elements of the services delivery. Seen within the context of servitization, the intangible elements of a service based strategy, has an immense impact on the enterprise as an entity, as clients will attempt to find more tangible clues from the institution's more tangible operational aspects (Grove et al 2002:394-395; Palmer 2008:10-11). It also places renewed emphasis on relationship management as an aspect of consideration in the formulation and implementation of the servitization strategy. As noted by de Wulf (2003:55) building client satisfaction, loyalty and profitability is not achieved overnight, it is achieved through sustained close relationships established with clients. The inherent intangibility of services, it is suggested, has refocused the traditional transactional marketing approach by placing greater emphasis on the creation of customer value and relationship development (De Wulf 2003:55). It is also stressed by Magnusson and Stratton (2000:21) that in personal-interactive services, social skills development is on par with the high level technical skills required for implementing the servitization strategy.

Perishability and simultaneity of services

Fitzsimmons and Fitzsimmons (2008:19) urge the reader to consider an empty airline seat, an unoccupied hospital or hotel room, an hour without a patient in the day of a dentist or doctor, each they suggests represents an opportunity lost forever as, in contrast to manufactured products, services cannot be stored. The traditional manufacturing paradigm is would seem is one of balancing out fluctuating variances in the supply and demand for products by means of establishing appropriate storage facilities. It is interesting to note in this regard that Piccoli, Brohman, Watson & Parasuraman (2009:368) claim that in practice a significant gap persists in our understanding of the optimal deployment of resources to support the customer service process. It could be argued thus that servitization requires manufacturers to make a paradigm shift in this regard, as services are simultaneously produced and consumed. If not positively experienced, differences in client expectations and experience during a service encounter cannot be corrected, due to the simultaneity of production and consumption (Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons 2008:19). The psychological dimensions of expectations and perceptions accentuate the more intangible aspects of services, such as client feelings and emotions, all of which are complex in nature and therefore unpredictable (Gilmore 2003:19). The picture that emerges is clearly one of a need for effective capacity management in formulating the servitization and services strategy (Magnusson & Stratton 2000:17), but also one of having to manage the complex socio-psychological or emotive aspects relating to services. It is insinuated therefore that manufacturing institutions need frameworks and new paradigms of management for dealing with the perishability and simultaneity characteristics of services, as they tend to reside outside their traditional frame of mental references. Importantly, Magnusson and Stratton (2000:67) very pertinently state that that their research findings indicate an inability of production-dominant institutions to address these abstractions in dealing with servitization.

ASPECTS TO BE CONSIDERED IN THE FORMULATION OF A SERVITIZATION STRATEGY

Some of the nuance differences that exist in relation to the manufacturing of products and services delivery have been briefly explored in the preceding discussion. Gebauer (2009:80) argues that despite substantial research on services related aspects, such as that emanating from the above exploratory literature study, most manufacturing institutions are still struggling to formulate and implement a service orientation in the business strategy. The IFM and IBM (2008:25) white paper similarly concludes that "businesses find it difficult to transform from a product to a service business model" and Magretta (2002:88) specifically claims that creating the new business model is "a lot like writing a new story that describes how the institution will function". The problem with this is that traditional manufactures appear to experience difficulty in compiling the script, as they have not acquired an insight into the intricacies associated with the strategic realignment, as a result of the nuance differenced that exist between services and products. A key aspect to be considered therefore in compiling a servitization strategy is the need for a change in the mental models and frameworks that inform the servitization strategy and process.

It would appear that the range of issues to be addressed is multidisciplinary and covers a wide range of issues to be considered. The Ifm and IBM (2008:10) white paper for instance claims that service science is seen as a "multidisciplinary" construct embracing all appropriate, but as yet not agreed, disciplines and functions. In effect adopting a service science approach can be seen as constituting an interdisciplinary activity which attempts to create an appropriate set of new knowledge to bridge and integrate various areas based on transdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary collaboration (Ifm & IBM 200810).

A key factor, although not explicitly stated in all instances, weaving its way through the discussion has been the need for a change in culture and in particular management mindsets, thinking or paradigms, in order to more effectively deal with the nuance differences briefly alluded to and the multidisciplinary nature of the services construct. The client for instance, as seen from the discussion, is attributed a dual role of consumer and producer, and consumption is concurrent with production (Magnusson & Stratton 2000:67). It is suggested that it is aspects such as this that fall outside of the realm of traditional manufacturing thinking and experience, which require new frameworks and mental models in order to more effectively manage the servitization process. Traditional manufacturing reference frameworks are not necessarily people and relationship development orientated, but tends to focus on transactions and the strategic aspects associated with production such a total quality management. An aspect to be considered therefore is the nurturing of multidisciplinary social networks. The interaction and discussion that takes place within these networks will facilitate a shift from knowledge silos to webs of shared knowledge and multidisciplinary points of view that is essential in addressing the product service nuance differences that exist (Ifm & IBM 2008:11). Suggested therefore is the use of multidisciplinary task or project teams to engender a wider range of knowledge and experiential learning in implementing the servitization strategy. It needs to always be kept in mind that "services science" is still a relatively new field, one that is constantly evolving as research findings inform practitioners understanding of the intricacies associated with servitization. Many individual strands of knowledge and expertise relating to service systems already exist, but they often lie in unconnected silos and a multidisciplinary approach is deemed essential for bridging knowledge gaps and informing the learning process that takes place (Ifm & IBM 2008:1).

A common theme that Magnusson and Stratton (2000:21,22,52) encountered in interviewing managers who had undertaken a servitization process, was the stress placed on the need for additional services related skills to compliment an existing manufacturing skills base. Three principal employee skills participants apparently listed as being indispensable were an external focus, customer accessibility and solution orientated thinking (Magnusson & Stratton 2000:53). Advocated in the IfM and IBM (2008:11) white paper is the need for what is termed T-shaped professions "who are deep problem solvers with expert thinking skills in their home discipline but also have complex communication skills to interact with specialists from a wide range of disciplines and functional areas". Clearly this resonates with the multidisciplinary focus required, as alluded to above. Mills, Neaga, Parry and Crute (2008:9) very definitely state that there needs to be a recognition that much of the services strategy and "plan will be about building importing and sustaining new skills". This contention would seem to be supported by Camuti's (2006:2) assertion that "preparing future engineers in the Age of Globalisation requires additional skill sets beyond traditional technical capabilities, skill sets drawn from the humanities, social sciences and above all foreign languages".

A research study undertaken at the University of Pretoria's Graduate School of Technology Management (GSTM) revealed the need for services management related skills in order to assist government business and industry in their servitization efforts. A similar research study at the University of Kebangsaan in Malaysia revealed that the university faced many challenges in equipping graduates with the right skills and attitudes, so as to ensure that they would be employable (Mukhtar, Abdullah, Hamdan, Jailani & Abdullah 2009:357). The shift from a predominantly manufacturing to a services based economy, it is claimed by Mukhtar et al (2009:357), typically reflects such a challenge. An important conclusion derived from the research conducted by Mukhtar et al (2009:357), was that services economy graduates needed to work in multidisciplinary teams to deal with multifaceted complex problems and therefore required were, what the researchers termed to be, "adaptive innovators". In the IfM and IBM (2008:1) white paper a very definite correlation is drawn between adaptive innovators and a T-shaped people skills profile. Notably in this regard, Ziegler's (2007:1) research study also suggests that often engineering students are equipped with the technical knowledge they require in the workplace, but lack the so called soft or engineering management skills they also need.

It is suggested, that in terms of the insights derived from this discussion, that key aspects to be considered in formulating and implementing a servitization strategy are the need for a very fundamental change in both traditional manufacturing based skill sets and mental models or paradigms. The latter are deemed to be critical as they underpin the culture that exists within the institution and serve as behavioural and perceptual determinants, both of which play a vital role in the formulation and implementation of the servitization strategy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALAM I. 2006. Removing the fuzziness from the fuzzy front-end of service innovations through customer interactions. Industrial Marketing Management, 35(4):468-480. [ Links ]

AN Y., LEE S. & PARK Y. 2008. Development of an integrated product-service road.map with QFD: A case study on mobile communications. International journal of Service Industry Management, 19(5):621-638. [ Links ]

BAINES T., LIGHTFOOT H., PEPPARD J., JOHNSON M., TIWARI A., SHEHAB E. & SWINK M. 2009. Towards an operations strategy for product-centric servitization. International journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(5):494-519. [ Links ]

BAINES T.S., LIGHTFOOT H.W., EVANS S., NEELY A., GREENOUGH R., PEPPARD J., ROY R., SHEHAB E., BRAGANZA A., TIWARI A., ALCOCK J.R., ANGUS J.P., BASTL M., COUSENS A., IRVING P., JOHNSON M., KINGSTON J., LOCKETT H., MARTINEZ V., MICHELE P., TRANFIELD D., WALTON IM. & WILSON H. 2007. State-of-the-art in product-service systems. Journal of engineering management. Available online: http://www.portaldeconhecimentos.org.br/index.php/eng/content/download/12808/128593/file/fulltext.pdf Accessed: 28 March 2009. [ Links ]

BAINES T.S., LIGHTFOOT H.W., BENEDETTINI O. & KAY J.M. 2009. The servitization of manufacturing A review of literature and reflection on future challenges. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 20(5):547-567 [ Links ]

BRAX S. 2005. A manufacturer becoming service provider: Challenges and a paradox. Managing Service Quality, 15(2):42-155. [ Links ]

CAMUTI P.A. 2006. Engineering the future: Staying competitive in the global economy. Online Journal for global engineering education, 1.1:1-6, http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oigee [5 July 2009] [ Links ]

DE PELSMACKER P. & VAN DEN BERGH J. 2003. The nature of services. In Van Looy, B., Gemmel, P., Van Dierdonck, R. (Eds), Services Management: An Integrated Approach, 2nd edition, Harlow: Pearson Education, pp.74-97. [ Links ]

DE WULF K. 2003. Relationship marketing. In Van Looy, B., Gemmel, P., Van Dierdonck, R. (Eds), Services Management: An Integrated Approach, 2nd edition, Harlow: Pearson Education, pp.55-73. [ Links ]

DESMET S., VAN LOOY B. & VAN DIERDONCK R. 2003. The nature of services. In Van Looy, B., Gemmel, P., Van Dierdonck, R. (Eds), Services Management: An Integrated Approach, 2nd edition, Harlow: Pearson Education, pp.3-26. [ Links ]

FITZSIMMONS J.A. & FITZSIMMONS M.J. 2008. Services management: Operations, strategy, information technology. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

FLIEß S. & KLEINALTENKAMP M. 2004. Blueprinting the service company: Managing service processes efficiently. Journal of Business Research, 57:392-404 [ Links ]

FRY T.D., STEELE DC. & SALADIN B.A. 1994. A service-oriented manufacturing strategy. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 14(10):17-19. [ Links ]

GEBAUER H. 2009. An attention-based view on service orientation in the business strategy of manufacturing companies. Journal of management psychology, 24(1):79-98. [ Links ]

GILMORE A. 2003. Services marketing and management. London: Sage. [ Links ]

GROVE SJ., CARLSON L. & DORSCH M.J. 2002. Addressing services' intangibility through integrated marketing communication: An exploratory study. Journal of services marketing, 16(5):393-411. [ Links ]

GUMMESSON E. 2002. Relationship marketing and a new economy: It's time for de-programming. Journal of services marketing, 16(7):585-589. [ Links ]

HOUGH J., THOMPSON AA., STRICKLAND A.J. & GAMBLE J.E. 2008. Crafting and executing strategy: Text, readings and cases, South African edition. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

IFM & IBM. 2008. Succeeding through service innovation: A service perspective for education, research, business and government. Cambridge, United Kingdom: University of Cambridge Institute for Manufacturing. [ Links ]

JACOB F. & ULGA W. 2008. The transition from product to service in business markets: An agenda for academic inquiry. Industrial marketing management, 37(3):247-253. [ Links ]

KINDSTRÖM D. & KOWALKOWSKI C. 2009. Development of industrial service offerings: a process framework. Journal of services management, 20(2):156-172. [ Links ]

KUMAR R. & MARKESET T. 2007. Development of performance-based service strategies for the oil and gas industry: A case study. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 22(4):272-280. [ Links ]

MAGNUSSON J. & STRATTON S.T. 2000. How do companies servitize? Available online: http://gupea.ub.gu.se/dspace/bitstream/2077/2448/1/Magnusson_2000_37.pdf. Accessed 20 April 2009. [ Links ]

MAGRETTA J. 2002. Why Business models matter. Harvard Business Review, 80(5):86-92. [ Links ]

MATHIEU V. 2001. Service strategies within the manufacturing sector: Benefits, cost and partnership. International journal of service industry management, 12(5):451-475. [ Links ]

MILLS J., NEAGA E., PARRY G. & CRUTE V. 2008. Towards a framework to assist servitization strategy implementation. Abstract 008-440, POMS 19th annual conference, LaJolla, California, 9-12 May. [ Links ]

MUKHTAR M., ABDULLAH Y.S., HAMDAN A.R., JAILANI N. & ABDULLAH Z. 2009. Employability and service science: Facing the challenges via curriculum design and restructuring. Paper presented at international conference on electrical engineering and informatics 5-7 August, Selangor, Malaysia offerings: A process framework. [ Links ]

OLIVA R. & KALLENBERG R. 2003. Managing the transition from products to services. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 14(2):160-172. [ Links ]

OSTERWALDER A. 2004. Understanding ICT-based business models in developing countries. International Journal Information Technology and Management, 3(2/3/4):333-348. [ Links ]

PALMER A. 2008. Principles of services marketing, 5th ed. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

PFEFFER J. 2005. Changing mental models: HR's most important task. Human resources management, 44(2):123-128. [ Links ]

PICCOLI G., BROHMAN M.K., WATSON R.T. & PARASURAMAN A. 2009. Process completeness: Strategies for aligning service systems with customers' service needs. Business Horizons, 52:367-376. [ Links ]

SCHMENNER R.W. 2009. Manufacturing, service, and their integration: some history and theory. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(5):431-443. [ Links ]

SEEL R. 2000. Culture and complexity: New insights on organizational change. Organisations & People, 7(2):2-9, May. Available online: http://www.new-paradigm.co.uk/culture-complex.htm. Accessed: 7 January 2010. [ Links ]

SHOSTACK G.L. 1984. Designing services that deliver. Harvard Business Review, January-February, 62(1): 133-139. [ Links ]

SPRING M. & ARAUJO L. 2009 Service, services and products: rethinking operations strategy. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(5):444-467. [ Links ]

TAX S.S. & STUART I. 1997. Designing and implementing new services: The challenges of integrating service systems. Journal of Retailing, 73(1):105-134. [ Links ]

TEBOUL J. 2006. Service is front stage: Positioning services for value advantage. New York: Palmgrave-MacMillan. [ Links ]

VANDERMERWE S. & RADA J. 1988. Servitization of business: adding value by adding services. European Management Journal, 6(4):314-324. [ Links ]

VARGO S.L. & LUSCH RF. 2008. From goods to service(s): Divergences and convergences of logics. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(3):254-259 [ Links ]

VOSS C.A. 2005. Alternative paradigms for manufacturing strategy. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 25(12):1211-1222. [ Links ]

WEEKS R.V. 2008. The services economy: A South African perspective. Management today, 24(2):40-45. [ Links ]

WEEKS R.V & BENADE S. 2009. Servitization: A South African perspective. Journal of Contemporary Management, 6:390-408. [ Links ]

WILSON A. 2008. Services Marketing: Integrated customer focus across the firm. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM (WEF). 2009. The Global Competitiveness Report 2009-2010. World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland. [ Links ]

ZIEGLER R. 2007. Student perceptions of Soft skills in mechanical engineering: ICEE 2007 conference. Cape Peninsula University of Technology, South Africa. [ Links ]