Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Males in predominantly female-dominated positions: a South African perspective

S van AntwerpenI; E FerreiraII

IDepartment of Office Management and Technology, Tshwane University of Technology

IIDepartment of Business Management, University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: This paper looks at the underrepresentation of male administrative support staff in the female-dominated occupational environment in South African and their perceptions of various intrinsic and extrinsic barriers that are experienced in executing their daily activities.

DESIGN/METHODOLOGY/APPROACH: This study encompassed a literature review and an empirical survey focusing on perceptions to determine the profile of male administrative support staff.

FINDINGS: Male administrative support staff is under-represented in trade and industry. Gender discrimination undoubtedly has an effect on the various barriers experienced by males in the traditionally female occupational environment.

PRACTICAL AND SOCIAL IMPLICATIONS: Leaders and managers in society should take every possible measure to decrease the existing sharp gender segregation in the corporate arena.

ORIGINALITY/VALUE: All discriminatory issues should be addressed by the leaders and managers to ensure not only equal opportunities for them, but also the value of all employees for the work they perform and not according to their gender. Every possible measure should be taken to decrease the existing gender segregation in the work environment and become more sensitive to issues relating to this topic. This will not only produce happier, but also probably ensure more productive employees and increased profits.

Key phrases: Administrative support staff, barriers, extrinsic, gender, perception, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

The role of administrative support staff is interesting, challenging and undergoing many changes, which makes this profession more appealing, even to males. The new tools of this trade, the enhanced electronic means of transmission and access to information position these workers on the cutting edge of information flow. Traditionally, occupational status and achievement have been crucial components of men's identity and their self-esteem, and men frequently believe that their own occupational success is not enough when they do not fulfil the expectations of people and industry.

For the purpose of this paper, administrative support staff will include office professionals, administrative officials, secretaries and personal assistants in all types of businesses, doing a variety of tasks such as clerical work, telephone reception work, stenography, computer programming, document compilation and the management of information and information systems.

Although the profession is changing, many people still see the secretary and administrative support staff as female jobs. According to Jobe-Kurang (2006:Internet), secretaries are becoming more known as office professionals and the role of the office professional can be expected to include some managerial duties. Jobe-Kurang (2006:Internet) then mentions the roles and qualities of a secretary in her article, and says the following: "How does a secretary prove that her role is changing and help to achieve the organisational goals?"

Many men in modern society are actively attempting to achieve a more rewarding balance between family and career commitments. Women who work away from home, especially in the traditionally male-dominated professional occupations, often gain higher status, self-esteem and a sense of control over their lives. The men who select non-traditional "male" careers, are frequently viewed as being "out of the ordinary" or "effeminate". Men have less support from outsiders than women for making gender-atypical career choices. Males have certain roles to fulfill, whereas females have their unique traditional identified roles. However, most of the roles attached to each specific gender are mere perceptions created by society and have been sustained and upheld through the centuries (Anon 2010:Internet; Shriver 2009:Internet).

This South African-based study was necessitated by the reality that males, especially male office or administrative managers, are crossing over to a traditionally female-dominated occupational environment. Careers are often stereotypically classified into "male's work" and "female's work". Even male office management learners in higher education who pursue a career in the office management arena experience discrimination from the first level of their training (Van Antwerpen 2006:16). The following question arises: "Are trade and industry applying prejudiced practices?" In industry, this scenario includes female office managers, male and female managers as well as male colleagues working in various positions in the corporate arena. Males are less likely than females to aspire to work in a gender-atypical profession. While the proportions of females in several male-dominated professions (eg the mining industry, the legal field and the medical field) have dramatically increased over the past number of years, predominantly female professions have hardly, if at all, changed their gender compositions. Bringing males into one's analysis of this segregation has the potential to transform one's sociological understanding of how gender operates in the working environment. For too long, the study of occupations has been conducted with either a gender-neutral framework or with the focus on the disadvantaged female in a male-dominated field (Shriver 2009:Internet).

The aim of this paper is to investigate the underrepresentation of male office managers in South African trade and industry and their perceptions of various intrinsic and extrinsic barriers that are experienced in executing their daily activities. The investigation was based on an in-depth literature review and an empirical study.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

The under-representation of male administrative support staff

Males have been under-represented for many years in the administrative support staff environment, and this is still the case today. A number of male secretaries commented on their profession and the dominance of females in it. According to US Labour Department figures in 1995, only 1.5% of the 3 361 000 secretaries in the USA were males. Professional Secretaries International, an association for office professionals, had 27 000 members of whom fewer than 1% were males. However, more men are entering the profession in computer-related positions (Anon 1996:Internet) and the number of male secretaries is increasing steadily (Jones 1996:Internet).

The underrepresentation of male administrative support staff in South Africa is also clear when looking at the membership of the Association for Office Professionals of South Africa. In February 2010 the Association had a membership of just under 30 000, of whom fewer than 5% were males. According to Brown (2010:Interview), this percentage is slowly increasing, and most of these males are from the governmental sector with few from the private sector.

Men in these jobs are referred to, inter alia, as gay and unambitious (Rudolph 2008:6) and these perceptions may form career barriers that prevent such men from achieving their goals.

In order to determine the profile of males in a nontraditional male occupation, the following concepts require clarification:

• career barriers;

• extrinsic barriers;

• intrinsic barriers;

• males in nontraditional male occupations; and

• equality on the grounds of gender.

Career barriers

Career barriers (extrinsic and intrinsic) can prevent an individual from attaining or succeeding in a goal. It can furthermore be regarded as a rule, law or policy that makes it difficult or impossible for something to happen or to be achieved. Career barriers can be devastating in many respects, to the extent that they arouse strong emotions. London (1998:xvii) emphasises that people react differently to career barriers, which include the following:

• thoughts, emotions and their interaction;

• the effects of one's resilience and toughness in reaction to stress;

• thought processes;

• strategies for coping with stress;

• developing insights about themselves, others and the situation; abd

• career motivation - patterns of personality characteristics, needs and interests that comprise career resilience, career insight and career identity.

Extrinsic barriers

Males in non-traditional occupations face career barriers that prompt them to process information carefully and objectively. They are able to move beyond their disappointment, anger, frustration and a host of other emotions. The conclusions that male office managers reach about the barriers that may affect them determine how they will manage a particular situation. Recognising the reasons for the barrier and the extent to which it can be controlled, reversed, ignored or overcome, will help an office manager to devise coping strategies (London 1998:xxi).

The word "extrinsic" can be defined as not contained or included within, extraneous, originating or acting from outside and external (Collins' cobuild 1999:389). Extrinsic incentives, such as remuneration, working conditions, recognition or promotion, are defined as incentives provided by the organisation or other external sources. Extrinsic rewards are furthermore additive, complementary or reciprocal.

Yuracko (2009:71-72) investigated a number of legal issues concerning gender and race in the workplace and found that these two factors are viewed differently. Although both issues are treated as biologically and physiological based and as having some recognisable external manifestations, race is merely associated with skin tone and not associated with meaningful differences. Gender behaviour seems natural and immutable and receives protection from workplace discipline. However, employees are more likely to find their workplace expressions of gender identity protected than their expressions of racial identity. Regarding the race issue, different obligations are not imposed on different race groups, as seems to be the case with gender differences.

Masculine and feminine qualities are not inherent in men and women respectively -they are the product of social beliefs. Men can do the work that is usually assigned to women and there is no reason why men should be better at leading and women better at caring. The problem, however, is to persuade men to do the work alongside women without fear or derision. In many instances, there is little connection between the jobs nurses do (and probably also administrative support staff) and the society's current construction of femininity. To be labelled a homosexual seems to be the main problem when men do not measure up to masculine expectations (Entwistle 2004:47).

The following perceptions on the skills and competence of workers also exist (Medved 2009:Internet):

• "Both sexes attribute more value to work performed by men than by women."

• Workplace and care-giving skills associated with femininity, more often than masculinity, are assumed to be unskilled.

• Men are rational because they are better decision makers, while women are more emotional because they are better caregivers.

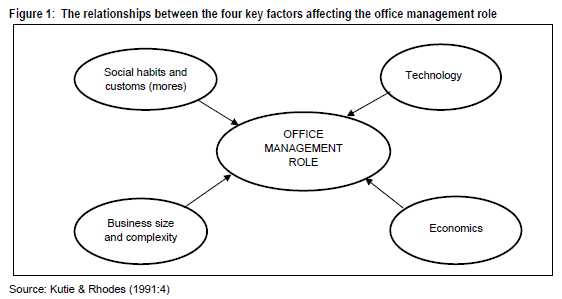

As conceptualised in figure 1, the office management role can be affected mainly by four significant factors, namely social conditions and mores, particularly the attitudes of workers towards their careers and the status of the office manager, the state of technological development, the size and complexity of the enterprise and economic conditions.

Intrinsic barriers

According to Collins' cobuild (1999:584), the term "intrinsic" means: belonging naturally, inherent or essential. As far as research is concerned, the term "intrinsic" can be seen as those values that cannot physically be touched, seen or isolated. These values come from within. Intrinsic, internal or personal obstacles/barriers are commonly recognised as shortcomings that may have a negative influence of employees.

Regardless of their sexual orientation, men in non-traditional male occupations, experience anxiety around the powerful stigmas associated with the homosexual status and face suspicions that they are gay (Simpson 2004:365; Skuratowics & Hunter 2004:98).

Research on male secretaries by Medved (2009:Internet) indicates that to overcome the barriers and stigmas relating to traditional female jobs, male secretaries occasionally describe their jobs and tasks in gender-neutral terms such as being an "administrative assistant" or "bookkeeper." They also say what they do in relation to the computer environment, mentioning the programmes they work with instead of using the term "secretary". Some even lie about what they do.

On a positive note, men can feel comfortable with 'female' discourses of service and care while drawing on resources from other, more privileged discourses to overcome any disadvantage associated with their minority status (Simpson 2004:366). Men in female-dominated occupations receive promotions more quickly than their female co-workers (Skuratowics & Hunter 2004:92).

Males in non-traditional male occupations

Golombok and Fivush (1994:202-204) assert that male occupations are accorded more prestige than traditionally female occupations and therefore propound that people in non-traditional careers are accorded less prestige than those pursuing traditional career goals.

Three reasons are advanced for men crossing over to a female-dominated career. Firstly, there is the presence or absence of the lure of economic rewards, either in terms of promising career prospects or the lack of alternative opportunities. The second key issue is the problem of damaged masculinity, which may result from entering a woman's career, and the development of new masculinities that may encourage men to disregard stereotypes. Their location in a feminised occupation requires the performance of emphasised femininity, including deference and care-taking behaviours. Men themselves play an active role in making choices and changing the patterns of segregation. Thirdly, technological change as an external factor often produces the context for degendering or regendering tasks (Henson & Rodgers 2001:219).

Earlier research indicated that men go into non-traditional jobs for the following reasons: a desire for a less stressful and aggressive lifestyle, greater ability to pursue interests and talents not available in male-type jobs, increased stability of the positions and the frequency of being able to interact with females on the job (Chusmir 1990 & Hayes 1989, in Heppner & Heppner 2009:53). Some studies also indicate that men in these non-traditional career fields were viewed in negative or distrustful ways by others. Men entering these positions may face obstacles such as discrimination and suspicion in relation to their motives as well as potential harassment because of societal biases (Heppner & Heppner 2009:63).

According to Palmius and Torsten (1997:Internet), men may choose to take up women's work for various personal reasons, such as:

• interests;

• talents;

• the lack of alternative opportunities (especially in a period of high unemployment);

• the distaste for stereotypically macho environments;

• the desire to work jointly with a partner; and

• the need to remain in a particular neighbourhood.

In the office management profession, men seem to have no particular interest in either changing the content or status of the career or forcing women out. They may simply be happy working in a predominantly female environment.

Male secretaries are acceptable, do well, are on the increase and women welcome men in the office. Males tend to use more computer packages, take more risks and are flexible in their approach (McGlaughlin, in Cambridge 2002:Internet).

A survey conducted in Australia revealed that the majority of employees believe that there should be more male secretaries in the workplace. With more female managers, this seems to be the way to go. Male office professionals are becoming more commonplace. Calder (2010:Internet) also remarks that the role of secretaries has changed dramatically over the last five years and that men are equally capable of doing the job.

Equality on the grounds of gender in the South African context

Equality entails the full and equal enjoyment of rights and freedom as stipulated in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (RSA 2000). The Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000 was promulgated to achieve equity in the workplace by:

• promoting equal opportunity and fair treatment in employment through the elimination of unfair discrimination; and

• implementing affirmative action measures to redress the disadvantages in employment experienced by designated groups to ensure their equitable representation in all occupational categories and levels in the workforce.

Subject to section 6 of the above-mentioned Act, no person may unfairly discriminate against any person on the basis of gender, including:

• gender-based violence;

• any practice, including traditional, customary or religious practice, which impairs the dignity of women and undermines equality between women and men, including the undermining of the dignity and well-being of the girl/boy child; and

• the denial of access to opportunities, including access to services or contractual opportunities for rendering services for consideration, or failing to take any steps to reasonably accommodate the needs of such persons.

Women are reported to be climbing the career ladder into executive careers far more quickly than their male counterparts are at a younger age. Nevertheless, the forces pushing for gender democratisation are still weak in relation to the scale of the problem. We are still in the early stages of the struggle for gender democracy on a world scale and, as that struggle develops, gender theory and research will have a number of roles to fulfil.

PROBLEM AND RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The problem examined in this study pertains to the discriminatory tendencies against men in the traditionally female administrative support staff environment. This was viewed against the background of the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000, focusing mainly on gender discrimination as a basis for this study.

The question arises whether trade and industry would accept male office managers or whether they would follow the status quo of having preference for the current dominant gender (females). In order to address this problem, the following objectives were identified:

• to investigate the underrepresentation of male office managers in the contemporary corporate arena;

• to identify perceptions of various intrinsic and extrinsic barriers experienced by males in executing their daily activities;

• to identify possible advantages and disadvantages experienced by males in a non-traditional male occupation; and

• to identify how males are viewed by female office managers as well as male and female managers in a non-traditional male occupation.

METHODOLOGY

This study encompassed a literature review and an empirical survey that focused on perceptions listed to determine the profile of males in a non-traditional male occupation. The empirical survey was conducted by means of structured questionnaires, which consisted of three sections: section A contained demographic data, section B involved stated perceptions using a five-point Likert-type scale and section C consisted of open-ended questions. Quantitative research methods were used on qualified male secretaries (n=22), female secretaries (n=120), as well as female office managers (n=120) and male and female employers (n=95) employed in both the private and public sectors in the Northern Gauteng region in South Africa. The research method was designed for measuring behavioural attitudes and determining a profile on administrative support staff in trade and industry and identifying intrinsic and extrinsic factors that may influence the role of males in the above-mentioned professions.

EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

Demographic information of male secretaries

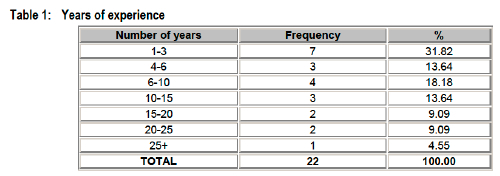

The respondents had to indicate on the questionnaire that was completed by male secretaries, the number of years of experience they had in their present profession, as reflected in table 1 below:

As indicated in table 1, the number of respondents with between one and three years' experience constituted the majority. This tendency may reflect the fact that more males are currently entering the corporate arena than in the past.

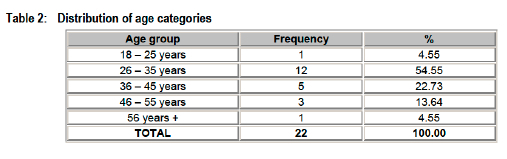

As indicated in table 2, the majority of the respondents (54.5%) were in the age group of 26 to 35, which represents a relatively young management corps.

General perceptions on male administrative support staff in the working environment

The following perceptions on male administrative support staff in the working environment were obtained from the respondents (male secretaries):

• A significant majority (96%) of the sample agreed that females are by default considered by employers to be better suited to a secretarial career.

• More than half (56%) of the sample agreed that they experience "female chauvinism" among colleagues.

• A total of 50% of the respondents agreed to the perception that males taking up a non-traditional occupation were viewed as being as less masculine by the opposite gender as well as by people of the same gender.

• Only 50% agreed that they would choose a career as office manager/secretary again should they have an opportunity to do so.

• A total of 60% of the sample agreed that they were excluded from participation in office gossip as a result of their gender.

• The majority of respondents (77%) disagreed that most of their tasks were of a feminine nature.

• Regarding the perception of managers underestimating their abilities in their profession, 55% agreed.

• With regard to the perception of the importance of what their male colleagues think of their abilities to perform their daily tasks, 68% agreed.

• A total of 63% of the respondents earned an annual remuneration package of less than R79 000 (during 2009), and had to support their families as breadwinners.

• Only 50% of the respondents agreed with the statement that they had to change their attitudes of prejudice towards an office management career as being exclusively for females.

• The majority (72.72%) indicated that they trusted female managers not to discriminate against them because of their gender, which is a positive remark.

• A total of 55 % of the male sample agreed that female colleagues' opinions of their (a male in an atypical male occupation) ability to perform their office tasks were important to them.

• This implies that they viewed recognition of their performance as important and that this recognition had an influence, either negative or positive, on their self-esteem.

• The large majority of male office managers (69%) agreed with the fact that their male colleagues' perceptions of their abilities to perform their tasks were important to them. Their abilities should be judged, irrespective of their gender.

Perceptions of the advantages or disadvantages of being a male office manager

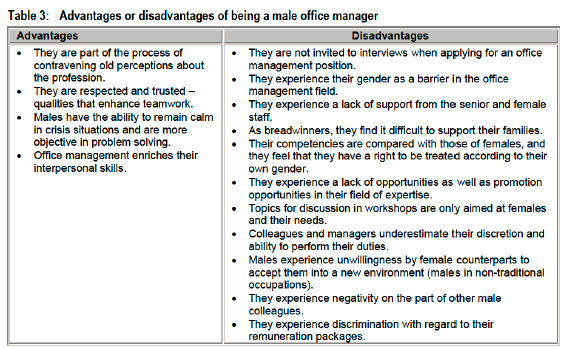

Table 3 indicates the responses to an open-ended question requiring the respondents in each group to indicate what they regarded as the advantages or disadvantages of being a male office manager.

It is interesting to note that the list of disadvantages outlined by male office managers is far more extensive than the list of advantages of being a male office manager. The advantages are positive and thus an indication that male office managers are fulfilled by the challenges their profession provides. It is, however, evident that males in a non-traditional occupation do experience both intrinsic and extrinsic barriers, which have a negative influence on the male office manager. Most of the barriers experienced by male office managers can be directly related to the attitudes of their managers as well as feedback from female colleagues' attitudes.

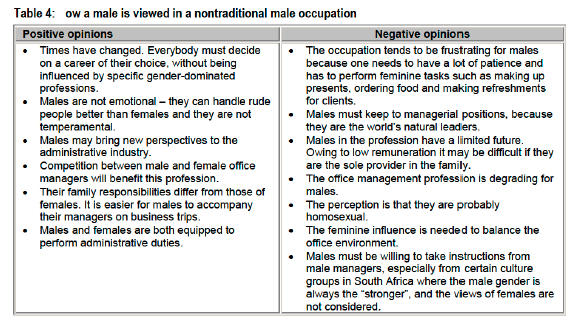

Perceptions of how a male is viewed in a non-traditional male occupation

Table 4 shows the positive and negative opinions of how female office managers as well as male and female managers view a male in a non-traditional male occupation.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The literature sources explored clearly indicate that male administrative support staff are still underrepresented in South African trade and industry. This is also the situation in the USA. Although male secretaries and office professionals are still something of a rarity, the number is increasing steadily. Whether this number actually needs to be representative, however, is questionable.

The study reveals that gender discrimination definitely has an effect on the various intrinsic and extrinsic barriers experienced by males pursuing a profession in a non-traditional male occupational environment. It is recommended that the fallacies that exist concerning the preferred gender for the secretarial profession should be replaced by fair and equal opportunities in the corporate arena. More opportunities for the minority gender group should be made available. Trade and industry should refrain from classifying professions as being either male or female dominated.

With a view to eliminating negative barriers, the following recommendations are made about males in non-traditional occupations:

• There is a need to revise salary packages by determining the extent to which they are market related in comparison with other occupations, where the same levels of training, responsibilities and working conditions apply. Males should receive recognition for their abilities, skills and professionalism and should not be compared to females in the profession. They should be viewed as unique individuals because each gender has its own exceptional qualities and characteristics.

• Male managers and colleagues should not discriminate against male office managers because they perform duties considered to be female oriented. It is therefore recommended that managers as well as male colleagues should take cognisance of the fact that discrimination against males performing duties in a non-traditional occupation is unacceptable. It is more important for them to recognise the professional execution of duties.

• Male office managers should receive the same treatment as their female counterparts when applying for a vacant position. They should not be rejected because of their gender and should have the same right to be invited for interviews where they could have an equal opportunity to market their skills.

• Trade and industry should refrain from classifying professions as being either male or female dominated. The Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000 endeavours to facilitate the granting of equal opportunities to all individuals, regardless of their gender, disabilities, race, age and religion. It is therefore imperative that the above-mentioned Act should be implemented in all sectors of the economy.

• A balanced approach to the appointment of candidates from both genders in the administrative field should be sustained in the corporate environment.

• Descriptions of male office managers need to be included in literature sources used for study material at higher education institutions.

• The fact that male and female office managers are often perceived in gender-specific terms probably limits the capacity of males to challenge females for many of the most prestigious administrative professions. While it may be to the benefit of the females that gender definitions are extended in this way in the short term, it will ultimately be necessary to challenge the gender meaning of "secretary" to ensure that it does not continue to limit the areas available to females. This involves not only a change of label but also hinges on the discursive frameworks with which meanings are constituted (Pringle 1993).

• When the organisers of seminars, workshops and conferences select topics for discussion, they should ensure that these are suitable and applicable to males and females in the profession.

• The corporate gifts handed out during registration at the above-mentioned events should be suitable for males and females. The organisers should be careful not to include only female gifts such as make-up and perfume.

• Speakers at seminars, workshops and conferences need to be made aware of the fact that there are male delegates and that they should present their topics accordingly. They should not refer to the female identification only, for example "she" and "hers" continuously. Males attending these functions should not feel excluded from the event.

• Every possible measure should be taken to decrease the existing sharp gender segregation in the work environment.

The Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000 endeavours to facilitate the granting of equal opportunities to all individuals, regardless of their gender, disabilities, race, age and religion. It is therefore imperative for the above-mentioned Act to be implemented in all sectors of the economy. However, it should be emphasised that when males cross over gender-specific boundaries, traditionally female occupations should not be modified to incorporate traditional masculine ideals and sociostructural elements of patriarchal privilege. The bottom line is that work should ultimately be a satisfying, non-discriminatory experience.

All discriminatory issues should be addressed by the leaders and managers in society to ensure not only equal opportunities, but also value all employees for the work they perform and not according to their gender. The corporate environment should take every possible measure to decrease the existing sharp gender segregation in the work environment and become more sensitive to issues relating to this topic. In conclusion, in the words of Sigmund Freud: "No other technique for the conduct of life attaches the individual so firmly to reality as laying emphasis on work; for his work at least gives him a secure place in a portion of reality, in the human community" (Freud 2010:Internet).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANON. 1996. Male secretaries: a minority but no longer a novelty. [Internet: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1077/is_n10_v51/ai_18544357/ downloaded on 2010-02-03. [ Links ]]

ANON. 2010. Gender roles: gender roles and feminism. [Internet: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gender_role downloaded on 2010-02-08. [ Links ]]

BROWN S. 2010. Award convener of the Association for Office Professional of South Africa. Statement to the authors, 3 February. Pretoria. [ Links ]

CALDER R. 2010. Male secretaries the new status symbol. [Internet: http://www.girl.com.au/male-secretaries.htm downloaded on 2010-01-28. [ Links ]]

CAMBRIDGE D. 2002. Male secretaries. [Internet: http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2002/jul/29/careers.jobsadvice7 downloaded on 2010-01-28. [ Links ]]

COLLINS' COBUILD. 1999. Learners' dictionary. London: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

ENTWISTLE M. 2004. Women only? An exploration of the place of men within nursing. Master of Arts (Applied), Victoria University, Wellington. [ Links ]

FREUD S. 2010. Sigmund Freud Quotes. [Internet: http://home.att.net/~quotations/sigmundfreud.html downloaded on 2010-04-07. [ Links ]

GOLOMBOK S. & FIVUSH R. 1994. Gender development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

HENSON K.D. & ROGERS J.K. 2001. "Why Marcia you've changed!" Male clerical temporary workers doing masculinity in feminised occupations. Gender & Society, 15(2):218-238. [ Links ]

HEPPNER M.J. & HEPPNER P.P. 2009. On men and work: taking the road less travelled. Journal of Career Development 36, (1):49-67. [ Links ]

JOBE-KURANG M.S. 2006. Role of a modern secretary. [Internet: http://archive.thepoint.gm/Opinion%20-%20Talking62.htm downloaded on 2009-12-02. [ Links ]]

JONES H. 1996. Be nice to the secretary, he could be the boss one day. [Internet: http://www.independent.co.uk/student/career-planning/be-nice-to-the-secretary-he-could-be-the-boss-one-day-1325753.html downloaded on 2010-02-02. [ Links ]]

KUTIE R.C. & RHODES J.L. 1991. Procedures for administrative support in the automated office. 3rd edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

LONDON M. 1998. Career barriers: how people experience, overcome, and avoid failure. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

MEDVED C. 2009. Gender crossing, work-family configurations and career outcomes. [Internet: http://wfnetwork.bc.edu/encyclopedia_entry.php?id=15464&area=All downloaded on 2010-01-18. [ Links ]]

PALMIUS W. & TORSTEN Y. 1997. Miss Sture and other masters. [Internet: http://web.telia.com/~u85824595/froken_sture.pdfdownloaded on 2010-01-27. [ Links ]]

PRINGLE R. 1993. Male secretaries, in Doing "women's work": men in non-traditional occupations, edited by CL Williams. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage:128-167. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2000. Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act of 2000.. Government Gazette 416, 9 February (Regulation Gazette No. 20876):4. [ Links ]

RUDOLPH M.A. 2008. Librarians in film: a changing stereotype. Master's Paper, University of North Carolina, North Carolina. [ Links ]

SHRIVER M. 2009. The Shriver Report: a woman's nation changes everything. [Internet: http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2009/10.womans_nation.html/ downloaded on 2010-02-09. [ Links ]]

SIMPSON R. 2004. Masculinity at work: the experiences of men in female dominated occupations. Work, Employment and Society, 18(2):349-368. [ Links ]

SKURATOWICS E. & HUNTER L.W. 2004. Where do women's jobs come from? Job segregation in an American Bank. Work and Occupations, 31 (1):73-110. [ Links ]

VAN ANTWERPEN S. 2006. Profile of male office management learners in a non-traditional male occupation: a South African perspective. International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations, 6(1):15-24. [ Links ]

YURACKO K.A. 2009. The antidiscrimination paradox: why sex before race? North-Western University School of Law, Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series, Paper No. 09-09. Chicago. [ Links ]