Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of Contemporary Management

versión On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The understanding and practice of value management by South African construction and project managers: exploratory findings

PA BowenI; PJ EdwardsII; KS CattellI; IC JayI

IDepartment of Construction Economics and Management, University of Cape Town, RSA

IISchool of Property, Construction and project Management, RMIT University, Australia

ABSTRACT

The nature and extent of value management (VM) practice by professional construction managers and construction project managers in South Africa is investigated using a web-based, online questionnaire survey. The survey explores managers' awareness and understanding of VM, and the nature and extent of the use of VM techniques within their organisations. Descriptive statistics are used to analyse the survey response data. The results suggest that awareness of VM is not widespread among construction managers and construction project managers, and that its actual practice is minimal. This is due largely to the encroachment on the traditional aims of VM by other project management techniques that also seek to facilitate the attainment of value for construction clients. Where VM is used on projects, it is invariably cost-minimisation driven in terms of both the project and the VM process itself. It is recommended that the professional association responsible for the regulation of the activities of construction and project managers should organise suitable training opportunities in value management.

Key phrases: Value management, construction and project managers, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

This paper forms part of a larger study examining the practice of value management (VM) by built environment professionals in South Africa. Previous papers have documented the VM practices of professional quantity surveyors (Bowen, Cattell, Edwards & Jay 2010), architects (Bowen, Jay, Cattell & Edwards 2010), and consulting civil, mechanical and electrical engineers (Bowen,Edwards, Cattell & Jay 2010c). In this paper, using the same survey instrument, the VM practices of professional construction managers and construction project managers (CM/CPM) are examined. Certain overlaps are inevitable given the need to discuss the results within the context of the literature.

The paper commences with a brief background review of VM research relating to the construction industry, followed by a description of the survey design and administration. The findings of the survey response data are presented and discussed. Conclusions are then drawn from the findings and recommendations made.

VALUE MANAGEMENT AND ITS APPLICATION TO THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

The historical origin and development of value management is well documented (see, for example, Macedo, Dobrow & O'Rourke 1978; Kelly, Male & Graham 2004).

Value management may be regarded as 'a structured and analytical process aimed at achieving value for money by providing necessary functions (in projects, processes or systems) at the lowest cost consistent with required standards of quality and functionality (Standards Australia 2007). Kelly et al (2004) state that VM is the name given to 'a process in which the functional benefits of a project are made explicit and appraised consistent with a value system determined by the client (see Kelly 2007:435). In this context, a project is seen as 'an investment by an organization on a temporary activity to achieve a core business objective within a programmed time that returns added value to the business activity of the organization' (Kelly 2007:435).

The process of VM is founded on a structured methodology or framework. Male, Kelly, Fernie, Grönqvist and Bowles (1998a) provide a 'good practice' VM framework based on results emanating from an international benchmarking study (Male, Kelly, Fernie, Grönqvist & Bowles 1998b). Other good practice standards or guides include the SAVE International Value Standard (SAVE International 2007), the Department of Trade and Industry's Value Management guide (DTI 1997), the Australian Standard: Value Management (Standards Australia 2007), and Defence Estates Organization's Value Planning and Management guide (DEO 1998).

Whilst VM had its origins within the manufacturing sector, its application in the construction industry has been the subject of considerable research. Such VM research endeavors have been manifold, typically dealing with issues such as advocating the use of value management in construction (Dell'Isola 1982; Kelly & Male 1993; Connaughton & Green 1996; Kelly et al 2004); the analysis of building components (Asif, Muneer & Kubi 2005); best practice VM and benchmarking (HM Treasury 1996; Male et al 1998a, 1998b); VM for managing the project briefing and design processes (Fang & Rogerson 1999; Kelly, Hunter, Shen & Yu 2005; Yu, Shen, Kelly & Hunter 2005); adoption rates, inhibitors and success factors for the adoption of VM in the construction industries of individual countries (Palmer, Kelly & Male 1996; Fong & Shen 2000; Shen & Liu 2003; Liu & Shen 2005; Cha & O'Connor 2006); VM methodologies and techniques (Pasquire & Maruo 2001; Spaulding, Bridge & Skitmore 2005); VM performance measures (Lin & Shen 2007), the relationship between VM and quantity surveying (Kelly & Male 1988; Ellis, Wood & Keel 2005); the integration of risk and value management (Green 2001; Dallas 2006); group decision support systems (Shen & Chung 2002); group dynamics in VM (Leung, Ng & Cheung 2002; Leung, Chu & Xinhong 2003); the use of VM to enhance value on public sector projects (Fong 1999; Hunter & Kelly 2006); managing value as a management style (Male, Kelly, Grönqvist & Graham 2007); client value systems (Kelly 2007); and hard versus soft VM methodologies (Green & Liu 2007).

Some of the issues briefly highlighted here, relating to the nature and use of VM techniques, were investigated through the design and administration of a web-based online opinion survey of professional CM/CPM in South Africa. Targeting this profession was thought to be appropriate given its focus upon management relating to the procurement of buildings.

QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN

The survey questionnaire consisted of four sections. Section A focused on demographic information such as professional grouping, membership of value management associations, position within the organization, age and experience, and characteristics of the organisation. Section B sought to establish respondents' familiarity with the concept of VM. The questions in Section C examined the use of VM within the organisation. Factors explored included usage of VM, the focus of VM activities (cost, or value, or both), perceived usefulness of VM, and whether VM activities are predominantly handled internally to the organization or externally. Section D focused on the nature and extent of VM usage on projects. Questions in this section dealt with reasons for the adoption of VM, extent of VM use on projects, factors influencing the employment of VM, the relative importance of value-system factors such as capital costs and running costs, benefits perceived to be derived from using VM, VM methods employed on projects, international VM benchmarks or standards employed, and metrics employed for measuring project success.

METHOD OF DATA COLLECTION

Data were collected from professional construction managers (Pr.CM) and professional construction project managers (Pr.CPM) registered with the South African Council for the Project and Construction Management Professions (SACPCMP). The registration and professional activities of CM/CPM professionals in South Africa is regulated by the SACPCMP, a council established by statute. As at July 2008, 1083 construction managers and 2775 construction project managers were registered with the SACPCMP. A web-based, online questionnaire survey was utilized for data capture. This method of data collection facilitated the comparatively easy (and inexpensive) national coverage of every registered CM/CPM in South Africa. The web-based study had previously been piloted and found satisfactory. The full survey was launched in July 2008. The SACPCMP emailed all CM/CPMs (A/=1083; 2775), requested their participation in the survey, and provided a link to a URL where the questionnaire could be completed on-line. Email bounces, full mailboxes, and restrictions on company email accounts resulted in 377 delivery failures for the construction managers and 1272 for the project managers. Expressed in terms of the number of email deliveries (N=706; 1503), the response rates were 2% (n=12) for the CMs and 2% (n=28) for the CPMs.

An unresolved issue arises with online surveys of this nature: the inability to determine exact response rates. Since the invitation to participate was issued by the SACPCMP by email, there is no guarantee that each invitation message reached its intended destination; nor that it was actually opened by the recipient. While this is not considered to be a serious problem for the validity of the survey, it does show that sample selection for online surveys can present difficulties. The survey response of 40 CM/CPM is therefore indicative and considered suitable for exploratory findings.

Further, it is conceded that the survey respondents constitute a self-selecting sample that may hold strong views (one way or the other) about VM and thus have the potential to be not completely representative of all CM/CPM professionals in South Africa. This potential weakness in the survey will be addressed in future research using qualitative case study research methods as a means of triangulating the primary data and providing the opportunity to explore relevant issues at greater depth.

DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

The survey data were analysed using SPSS Version 16.0 for Mac statistical application software, delivering mainly descriptive statistics. Unless otherwise stated, percentages given below relate to the responses to individual questions. In this section the results are described and discussed within the context of the literature. Given the low response rate, cross-tabulation was not undertaken to establish degrees of association between responses and whether the respondents were CMs or CPMs.

Demographic profile of survey respondents

The respondents comprised 30% (n=12) CMs and 70% (n=28) CPMs. The majority of respondents are employed in the private sector (73%) within the construction industry. Membership by respondents of value management organisations such as the Institute of Value Management (IVM) or SAVE International is non-existent. A minority (36%) is also registered with the Engineering Council of South Africa (ECSA). Most respondents are older than 45 years (70%), with 85% over 40 years. Eighty-three percent of respondents claim to have sixteen or more years experience in the industry, and 64% have been with the same organization for six or more years. Most respondents (44%) reported working for organizations consisting of more than thirty professionals, although 36% claimed to work for firms employing five or less professionals (bi-modal distribution). Whilst a considerable proportion of organizations (40%) are reported to enjoy a gross turnover in building project value in excess of R500m per annum (see Note 1), an equal percentage (40%) reported a turnover of less than R200m per year. The respondents may generally be described as experienced CMs and CPMs in private practice.

Awareness and use of value management

Of the 40 participants in the survey, 43% (n=17) claimed to be familiar with VM. Of these (n=17), respondents reported various ways in which they had heard about VM, namely: from an academic institution or from attending a VM course (47%); from within their own organization (29%); via the internet (12%); and Other' means (12%). Interestingly, none of the respondents reported hearing about VM from their professional institution. Other' sources included experience and general reading', exposure to a design firm involved in a joint venture contract, and being sent by a firm of quantity surveyors to a specialist VM training workshop in Australia.

Actual usage of VM as a process is very low, being reported by 14% (n=5) of respondents. The uses to which VM is put include value optimisation (3%), least cost determination (68%), and both of these objectives (29%). Reasons for not using VM included: the company was not familiar with VM (74%); the company had another system in place (14%); a view within the organization that VM is ineffective (3%); and Other' (7%). Under Other', respondents cited use of pre-planning and cost analysis'; use of VM in an informal manner, or when called upon to do so by clients; that VM is part of normal quality management; and the use of space and cost norms.

Opinions regarding the usefulness of VM varied. The most widespread view (33%) (n=9) was that VM was very useful, and that it should be used on most projects. Less pervasive views were that VM was indispensible and should be used on all projects (26%), and that VM was occasionally useful and should be used on a few selected projects (26%). Only 4% of respondents thought that VM was not at useful at all. Reasons cited in support of these contentions were that there was a need for a structured approach to optimizing cost and functionality, that VM is part of a normal cost reporting system, that that the use of VM depends on the nature and context of the project, that VM is inherently part of project managers' thinking, and that VM is a useful tool for managing costs.

When questioned about whether VM activities are predominantly handled internally within the organization, external to the firm, or via a combination of both, respondents reported as follows: internally (72%); externally (14%); and a combination of both (14%). Reasons cited for this included the size of the project (48%), discretion of senior management (29%), organizational policy (19%), the availability of in-house expertise (5%), and 'Other' (24%). 'Other' reasons cited included the preference of some clients to use 'outside' resources, and the nature of the type of contractual arrangement (e.g. turnkey projects).

Nature and use of value management within CM/CPM organisations

This section reports on the nature and use of VM within CM and CPM organisations. Given the low reported usage of VM within firms as a formal process, the percentages here clearly represent minority views. Of those respondents who indicated that VM is used within their organisations, 38% stated that VM is used on all projects. A further 25% reported that VM is used on most projects, whilst VM usage in only rare cases is reported by 13% of participants. Of those participants who utilize VM, 55% stated that the adoption of a VM philosophy is part of organizational culture.

Reasons for using VM

Participants were questioned as to the reasons why VM is utilized by their organizations. Reasons cited were that VM is effective in reducing costs (57%), that it optimises value (43%), clarifies the project brief (29%), facilitates the achievement of functionality (29%), that the technique has become an organisational ('select box') internal requirement (14%), and that it results from pressure from management (14%). None of the respondents stated that it emanates from requests from clients. 'Other' views (14%) were that achieving value for a client is part of a normal professional service.

How VM is promoted within the organisation

Respondents reported that, where VM is used within their organizations, such use is primarily promoted by senior management (74%) and project managers (43%). Promotion of VM usage by quantity surveyors (14%) or by an in-house VM department (14%) appears to be minimal. Usage promotion by quantity surveyors is reportedly non-existent. The main reason cited for the initial adoption of VM by the organization was requests from project sponsors and clients (33%). Interestingly, links with international organizations or overseas parent companies (17%) was not a strong influence. Keeping abreast of local competition that makes use of the practice had no influence at all. 'Other' reasons (50%) included the claim that VM is an integral part of project management, that it is 'good practice', that it facilitates maximizing profits, and that it permits rapid response in an industry with narrow margins.

Client value system variables

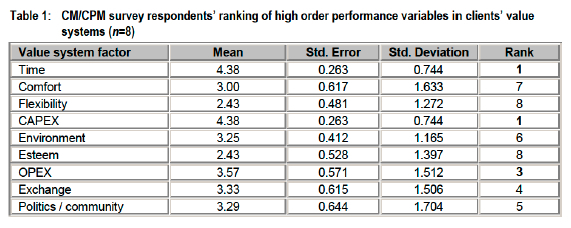

Kelly (2007) found that the variables in construction clients' value systems are the nine, high order, non-correlated performance variables of capital expenditure (CAPEX), operating expenditure (OPEX), time (duration of the project), esteem, environment, exchange, politics / community, flexibility and comfort. Drawing on this work and using Likert scales, participants were requested to indicate on a scale of 1 to 5 (1=completely insignificant; 5=extremely significant) their opinion as to the relative importance of these factors to project success. The results are depicted in Table 1. For the sake of clarity, 'CAPEX' refers to the investment capital expended on the project necessary for completion and hand-over; 'OPEX' constitutes the running costs accrued after project hand-over, over the operating life required by the client; 'esteem' refers to the prestige and benefits to the client that stem from the project; 'environment1 refers to the anticipated effect that the project will have on the surrounding eco-system (e.g. carbon imprint); 'exchange' is the project net worth to the client; 'politics / community' comprises issues relating to the project's impact on the surrounding community as well as political considerations; 'flexibility' refers to the flexibility offered b the project in terms of how easily it may be configured to meet different requirements; and 'comfort' relates to the usability of the project in terms of convenience and comfort.

Clearly, C Ms/CP M s perceive CAPEX and 'time' to be the most important factors in determining project success for a construction client, with 88% stating that capital expenditure and 'time' are very important considerations. Reduced operating expenditure is considered the next most important variable, followed by 'exchange' and 'politics/community'. Issues of 'environment' and 'comfort' then follow as the next most important considerations. Design flexibility is considered the least important factor to clients. It is worth noting that 63% of respondents consider environmental impacts to be moderately significant at best.

Outcomes of VM

The use of VM is claimed to, inter alia, result in cost savings, improvements in functionality, or a combination of both. When questioned about cost savings that are considered to typically flow from the use of VM on projects, 34% of respondents reported savings of up to 5%. A further 33% and another third of respondents reported savings of up to 10% and 15%, respectively. Similar sentiments were expressed regarding improvements in functionality and quality. More specifically, 67% reported improvements of up to 5%, whilst a further 17% and 16% claimed that improvements of up to 10% and 15%, respectively, were typical.

Client objectives for VM

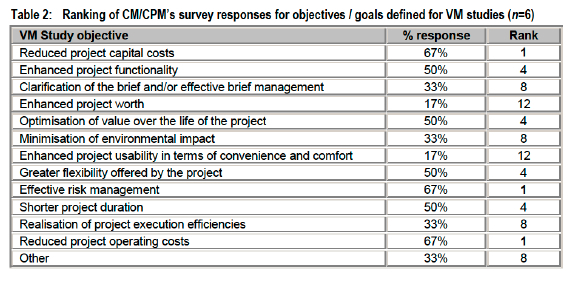

Value management studies can occur at various stages of a project and can be undertaken for a variety of reasons. Participants were presented with a list of VM objectives or goals drawn from the literature (e.g. Kelly et al 2004; Kelly 2007) and requested to indicate which of those factors had been the focus (objective) of VM studies with which they had personally been involved. The results are shown in Table 2.

Value management practice within the SA construction industry focuses primarily on the potential for reducing the capital cost of projects (67%), reducing operating costs (67%), effective risk management (67%), optimizing the value of the project over its life (50%), enhancing project functionality (50%), achieving shorter project durations (50%), and enhancing project flexibility (50%). Other foci, but receiving less attention, include minimizing the environmental impact of the project (33%), the realization of project execution efficiencies (33%), and the clarification of the project brief (33%). Enhancing project worth (17%) and usability (17%) appear to be lesser considerations. Respondents declined to offer additional objectives under 'Other'.

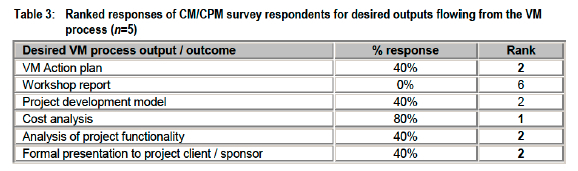

Respondents were questioned regarding desired outcomes expected to flow from VM studies on projects. A range of outcomes were provided, namely, a VM action plan; workshop report; project development model; cost analysis of the project; analysis of project functionality; a formal presentation to the project client / sponsor; and 'Other'. The results are shown in Table 3. In responding to this question, the CMs and CPMs displayed a clear preference for a cost-based outcome, favouring a detailed cost analysis (80%) above all others. The remaining outputs did not enjoy majority support (< 40%). No additional suggestions were offered under 'Other'.

VM team dynamics

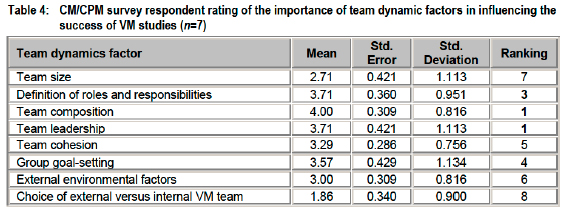

Given the importance of team dynamics in effective VM (see Fong, Shen & Cheng 2001; Leung et al 2003; Yu, Shen, Kelly & Hunter 2007), respondents were presented with a number of factors relating to team dynamics (e.g., team size, definition of roles, external versus internal VM team) and asked to rate their significance in terms of influencing the success of the VM exercise (1 = completely insignificant; 5 = extremely significant). The results are depicted in Table 4.

Participants rated team leadership and the composition of the team foremost in their potential to influence the effectiveness of a VM study. Factors also deemed to be influential include the clear definition of roles and responsibilities, group goal-setting, and team cohesion. Interestingly, the issue of whether the VM team is external or internal to the project was seen by respondents as the least influential factor.

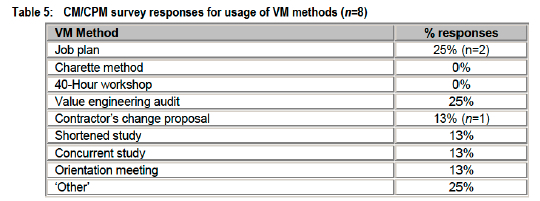

VM methods and tools

To assess the VM techniques employed in practice in the SA construction industry, respondents were presented with list of typical VM methods and asked to indicate whether or not they make use of them. Provision was also made for the use of 'Other' techniques. The results are given in Table 5. The most widely adopted VM methods are reported to be the value engineering audit (25%) and the job plan (25%). The remaining techniques enjoy minimal support (<15%). One participant providing information under 'Other' reported the use of 'cost reporting' systems.

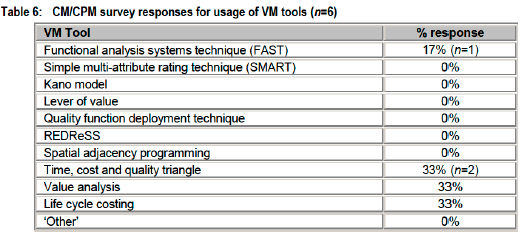

The usage of VM tools varies considerably amongst respondents (see Table 6). Of those who answered this question (n=6), a clear preference exists for tools associated with traditional practice, namely, life cycle costing (67%), time, cost and quality management (33%), and value analysis (33%). Interestingly, with the exception of the use of the FAST system (n=1 ), none of the other VM tools appear to be used at all. No additional tools were listed under 'Other'.

Benchmarking VM

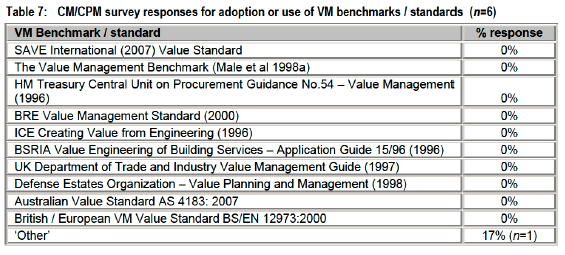

The literature refers to a variety of value management 'good practice' standards or benchmark guides. Examples include Australian Value Standard AS 4183-2007 (Standards Australia 2007), the British / European VM Value Standard BS/EN 12973:2000 (British Standards Institution 2000), and the SAVE International Value Standard (SAVE International 2007). Participants were presented with ten such benchmarks /standards and asked to indicate which (if any) they follow. The responses are shown in Table 7.

VM use in project briefing

The use of VM is promoted as a vehicle of clarifying the project brief (Kelly, Male & MacPherson 1993; Yu et al 2005). To examine the nature and extent of its use for this purpose in practice, participants were asked to indicate the VM methods used for brief clarification and the extent to which such methods are used. Of those who answered this question (n=6), 33% indicated that VM methods for briefing purposes are used in most if not all cases. Sixty-six percent claimed VM usage for briefing at most only in rare instances. When questioned about which VM methods are used for briefing purposes, the responses (n=4) indicated that the job plan (50%) is the most widely used technique. The value engineering audit (25%) also enjoyed support. It is noteworthy that the method typically associated with project briefing, the Charette, was not cited by respondents. No additional information was provided under 'Other'.

Integrating VM with risk and quality management

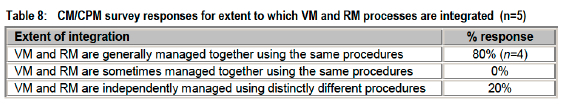

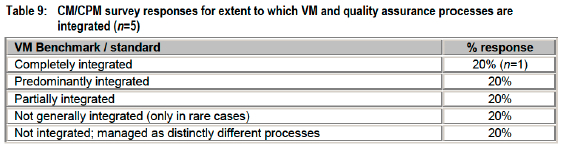

Ellis et al (2005) point to the integration of VM and risk management (RM) in practice, reinforcing the findings of Hiley and Paliokostas (2001) that practice is ahead of theory in this respect' (Ellis et al 2005:491). Interestingly, 80% of the respondent CMs and CPMs (n=5) reported that VM and RM are integrated and generally managed together as part of the management system (20%) stated that are independently managed). The results are shown in Table 8. Finally, participants were questioned regarding the extent to which VM is integrated with quality assurance procedures such as TQM and Six Sigma. The results are depicted in Table 9 (n=5). Integration is fairly widespread, but a large proportion (40%) reported integration at most only in rare instances. Only one respondent claimed complete integration.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has reported the findings of a web-based, online questionnaire survey into the nature and extent of value management (VM) practice by professional construction and project managers in South Africa. The survey explored practitioners' familiarity with, and understanding of, VM and the nature and extent of the use of VM techniques within their organisations.

The findings indicate that, within the practice of construction project management, VM has not evolved to become 'an established service with commonly understood tools, techniques and styles' (see Kelly et al 2004:48). The concept of VM is not widely understood and practiced by professional construction and project managers in South Africa. Despite an apparent appreciation of the benefits to be derived from the application of VM to projects, actual usage of VM is very low. South African construction and project managers appear to prefer other, more traditional, cost-based, methods of delivering value to projects. Those professionals that do practice VM predominantly see it as a cost minimization tool. Value management is perceived as capable of delivering significant savings in cost, improvements in functionality, and for clarifying the project brief. Given this, why is VM use not more widespread amongst South African construction and project managers?

Given the increasing globalization of construction, these findings serve as a cautionary note to South Africa construction and project managers. Active membership of dedicated VM organizations, although currently non-existent among the survey respondents, holds considerable potential for developing and refreshing respondents' VM skills.

The findings of this survey raise many new questions concerning VM practice in the South African construction industry. These issues will be addressed through further investigation, using a detailed case study approach with relevant stakeholders including professional associations. Particular attention will be paid to the drivers for, and barriers to, the use of VM. It is recommended that the SACPCMP initiates comprehensive programmes of continuing professional development activities designed to promote greater awareness and practice of VM. This exploratory study informs an agenda for the development of such VM expertise.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the staff of SACPCMP for emailing registered professionals inviting them to participate in the survey, and to John Bilay for his assistance with the logistics of the web-based survey and the processing of the data.

Notes

1 Currency exchange rate as at 19 April 2010: ZA Rands 11.32 = Pound Sterling 1.00; ZA Rands 7.43 = US$1.00.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ASIF M., MUNEER T. & KUBI J. 2005. A value engineering analysis of timber windows. Building Services Engineering Research and Technology, 26(2):145-155. [ Links ]

BOWEN P.A., CATTELL K.S., EDWARDS P.J. & JAY I.C. 2010. Value management practice by South African quantity surveyors. Facilities, 28(1/2):46-63. [ Links ]

BOWEN P.A., EDWARDS P.J., CATTELL K.S. & JAY I.C. 2010. The awareness and practice of value management by South African consulting engineers: Preliminary research survey findings. International Journal of Project Management, 28(3):285-295. [ Links ]

BOWEN P.A., JAY I.C., CATTELL K.S. & EDWARDS P.J. 2010. Value management awareness and practice by South African architects: exploratory survey findings. Forthcoming. Accepted Construction Innovation. [ Links ]

BRITISH STANDARDS INSTITUTION. 2000. BS EN 12973: 2000 Value Management. London: British Standards Institution. [ Links ]

BUILDING RESEARCH ESTABLISHMENT (BRE). 2000. Value from Construction: Getting Started in Value Management. Watford: BRE. [ Links ]

BUILDING SERVICES AND RESEARCH INFORMATION ASSOCIATION (BSRIA).1996. Value Engineering of Building Services. Application Guide 15/96, BSRIA, Berkshire: Bracknell. [ Links ]

CHA H.S. & O'CONNOR J.T. 2006. Characteristics for leveraging value management processes on capital facility projects. Journal of Management in Engineering, 22(3):135-47. [ Links ]

CONNAUGHTON, J.N. AND GREEN, S.D. 1996. Value Management in Construction: A Client's Guide. Special Publication 129, London: CIRIA. [ Links ]

DALLAS M.F. 2006. Value and Risk Management: A Guide to Best Practice. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

DEFENCE ESTATES ORGANISATION (DEO). 1998. Value Planning and Management. Technical Bulletin 98/26, DEO, Sutton Coalfield, USA. [ Links ]

DELL'ISOLA A. 1982 Value Engineering in the Construction Industry, 3rd Edition. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY (DTI). 1997. Value Management: A Quick Guide. London: DTI. [ Links ]

ELLIS R.C.T., WOOD G.D. & KEEL D.A. 2005. Value management practices of leading UK cost consultants. Construction Management and Economics, June 23:483-493. [ Links ]

FANG W.H. & ROGERSON J.H. 1999. Value engineering for managing the design process. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 16(1):42-55. [ Links ]

FONG P.S-W. 1999. Organisational knowledge and responses of public sector clients towards value management. The International Journal of Public Sector Management, 12(5):445-454. [ Links ]

FONG P.S-W. & SHEN Q. 2000. Is the Hong Kong construction industry ready for value management? International Journal of Project Management, 18(5):317-326. [ Links ]

FONG P. S-W., SHEN Q. & CHENG W. L. 2001. A framework for benchmarking the value management process. Benchmarking. An International Journal, 8(4):306 -316. [ Links ]

GREEN S.D. 2001. Towards an integrated script for risk and value management. International Journal of Project Management, 7(1):52-58. [ Links ]

GREEN S.D. & LIU A.M.M. 2007. Theory and practice in value management; a reply to Ellis et al (2005). Construction Management and Economics, June, 25:649-659. [ Links ]

HILEY A., & PALIOKOSTAS P.P. 2001. Value management and risk management: An examination of the potential for their integration and acceptance as a combined management tool in the UK construction industry. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, London: Surveyor Publications. [ Links ]

HM TREASURY. 1996. Value Management Guidance. No.54, Central Unit on Procurement, London: HM Treasury. [ Links ]

HUNTER K. & KELLY J. 2006. The supporting factors that make VM an attractive option in meeting the best value requirements in the UK public service sector, in SAVE International Conference, http://www.value-eng.org/knowledge_bank/dbsearch.php?c=view&id=197&ref=dbse [accessed 2nd September 2008]. [ Links ]

INSTITUTE OF CIVIL ENGINEERS (ICE). 1996. Creating Value In Engineering. Design and Practice Guide, London: Thomas Telford. [ Links ]

KELLY J. 2007. Making client values explicit in value management workshops. Construction Management and Economics, 25(4):435-442. [ Links ]

KELLY J., HUNTER K., SHEN G. & YU A. 2005. Briefing from a facilities management perspective. Facilities, 23(7/8), pp.356-367. [ Links ]

KELLY J. & MALE S. 1988. A Study of Value Management and Quantity Surveying Practice. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, London: Surveyor Publications. [ Links ]

KELLY J. & MALE S. 1993. Value Management in Design and Construction. London: E. & F.N. Spon. [ Links ]

KELLY J., MALE S. & GRAHAM D. 2004. Value Management of Construction Projects. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

KELLY J., MALE S. & MACPHERSON S. 1993. Value Management - A Proposed Practice Manual for the Briefing Process. Research Paper, No.34, London: RICS. [ Links ]

LEUNG M., CHU H. & XINHONG L. 2003. Participation in Value Management. Report, RICS Education Trust, The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, London: Surveyor Publications. [ Links ]

LEUNG M., NG S.T. & CHEUNG S-O. 2002. Improving satisfaction through conflict stimulation and resolution in value management in construction projects. Journal of Management in Engineering, 18(2):68-75. [ Links ]

LIN G. & SHEN Q. 2007. Measuring the performance of value management studies in construction: critical review. Journal of Management in Engineering, 23(1):2-9. [ Links ]

LIU G. & SHEN Q. 2005. Value management in china: Current state and future prospect. Management Decision, 42(4):603-610. [ Links ]

MACEDO JR M.C., DOBROW P.V. & O'ROURKE J.J. 1978. Value Management for Construction. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

MALE S., KELLY J., FERNIE S., GRÖNQVIST M. & BOWLES G. 1998a. The Value Management Benchmark: A Good Practice Framework for Clients and Practitioners. Edinburgh: Thomas Telford. [ Links ]

MALE S., KELLY J., FERNIE S., GRÖNQVIST M. & BOWLES G. 1998b. The Value Management Benchmark: Research Results of an International Benchmarking Study. London: Thomas Telford. [ Links ]

MALE S., KELLY J, GRONQVIST M. & GRAHAM D. 2007. Managing value as a management style for projects. International Journal of Project Management, 25(2):107-114. [ Links ]

PALMER A., KELLY J. & MALE S. 1996. Holistic appraisal of value engineering in construction in United States. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 122(4):324-328. [ Links ]

PASQUIRE C. & MARUO K. 2001. A comparison of value management methodology in the UK, USA, and Japan. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 6(1):19-26. [ Links ]

SAVE INTERNATIONAL. 2007. Value Standard and Body of Knowledge. Society of American Value Engineers, Dayton, Ohio, USA, June. Available at: http://www.value-eng.org/pdf_docs/about/VM%20Standard%20Methodology.pdf [accessed 7th September 2007]. [ Links ]

SHEN Q. & CHUNG J.K.H. 2002. A group decision support system for value management studies in the construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 20(3):247-252. [ Links ]

SHEN Q. & LIU G. 2003. Critical success factors for value management studies in construction. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 129(5):485-491. [ Links ]

SPAULDING W.M., BRIDGE A. & SKITMORE R.M. 2005. The use of function analysis as the basis of value management in the Australian construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 23(7):723-731. [ Links ]

STANDARDS AUSTRALIA. 2007. Australian Standard: Value Management (AS 4183 - 2007). Council of Standards Australia, Australia. [ Links ]

YU, A. T. W., SHEN, Q., KELLY, J. AND HUNTER, K. 2005. Application of value management in project briefing. Facilities. 23(7/8):330-342. [ Links ]

YU A.T.W, SHEN Q., KELLY J. & HUNTER, K. 2007. An empirical study of the variables affecting construction project briefing/architectural programming. International Journal of Project Management, 25(2):33-38. [ Links ]