Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of Contemporary Management

versión On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Exploring the relationship intention concept in two South African service industries

H DelportI; PG MostertI; TFJ SteynII; S de KlerkI

IWorkWell: Research Unit for Economic and Management Sciences; North-West University

IISchool of Business, Cameron University

ABSTRACT

Identifying customers who have the intention to build long-term relationships is beneficial for banking and life insurance organisations as it will afford marketers the opportunity to segment customers according to their relationship preferences. This may prevent money and resources being spent with little effect trying to develop a relationship with customers who do not intend to build a long-term relationship with the organisation. However, it is difficult to understand the nature of relationship intention without understanding the constructs used to measure relationship intention, namely involvement, expectations, forgiveness, feedback and fear of relationship loss. The purpose of this study is to determine whether these five relationship intention constructs are applicable to the banking and life insurance industries in Gauteng, South Africa. Data was gathered from 401 banking (n=202) and life insurance (n=199) customers. Findings confirm that the five constructs to measure relationship intention are applicable to the selected services and identified an additional four factors that support some of the five constructs. However, no differences were found between respondents with different relationship lengths and their views pertaining to the identified factors.

Key phrases: Relationship marketing, relationship intention, relationship length, banking, life insurance

INTRODUCTION

Organisations are increasingly focusing their marketing efforts on relationship marketing as competition, globalisation and the costs of attracting new customers increase (Anderson, Jolly & Fairhurst 2007:394; Mehta & Tambe 1997:129). At the core of relationship marketing is the development and maintenance of long-term relationships with valuable customers (Berry 1983:25; Egan 2004:21-22; Grönroos 1994:9). It is important to note that these long-term relationships with valuable customers have the ability to create value and therefore, help organisations to achieve sustainable competitive advantages (Marzo-Navarro, Pedraja-Iglesias & Rivera-Torres 2004:426). Organisations benefit from relationship marketing in terms of greater sales volumes, better operating efficiencies, positive word-of-mouth, improved customer feedback and decreased marketing expenses (Alexander & Colgate 2000:945; Claycomb & Martin 2002:616; Grönroos 2007:308). Organisations can also expect their profits to increase as the relationship between the organisation and its customers increase (Little & Marandi 2003:152), as customers' value to organisations can be determined by the length of the relationship between the parties - the longer the relationship, the greater the value to the organisation (Berger & Nasr 1998:19). Customers, on the other hand, benefit from relationship marketing in terms of enhanced value, better quality, and increased satisfaction with their purchases (Claycomb & Martin 2002:616; Little & Marandi 2003:33; Marzo-Navarro et al 2004:426).

Ward and Dagger (2007:283) argue that sixty to seventy percent of customer relationship initiatives have stalled or failed, despite the embrace of relationship marketing as an important corporate strategy. While there are many organisational and structural reasons for this, it is likely that relationship marketing initiatives are applied in service settings where relationships have limited meaning or relevance (Kinard & Capella 2006:365; Zolkiewski 2004:27), especially if some customers may not desire relationships with organisations. It is therefore important to examine the intentions of customers and to determine whether organisations need to adopt a transactional or relational approach when targeting different customer groups. Emphasis should therefore not be placed on developing relationships with all customers, as not all customers desire relationships with an organisation (Grönroos 2000:242; Zolkiewski 2004:25). Rather, it is important to focus on the development of relationships with the "right" customers.

By comparing customers' transactional versus relationship orientations, organisations can conduct an overall assessment of customers' profiles and segment them according to their relationship preferences. If the relationship intention of the customer is high, it will make sense to invest in building a relationship with the customer. Such relationships might be profitable in the long run, implying that the relationship marketing approach will be best suited to deal with customers showing relationship intention. Conversely, if customers' relationship intentions are low, it is not worth investing in building long-term relationships with them and a transactional marketing approach will be better suited (Kumar, Bohling & Ladda 2003:670).

The purpose of this article is to explore the relationship intention construct in two South African service industries, namely banking and life insurance. These industries were specifically chosen as banks and life insurance providers are known for the value they place on customer relationships and since customers who engage in a relationship within a bank and life insurer could perceive greater relational benefits (Kasper, Van Heldsingen & Gabbott 2006:124; Wong & Sohal 2006:259). The article will also consider the influence of relationship length on relationship intention.

THEORETICAL OVERVIEW

The theoretical overview focuses on relationship intention together with the five constructs associated with measuring relationship intention. The overview will be concluded by a discussion on relationship length.

Relationship intention

Kumar et al (2003:670) define relationship intention as a customer's intention to build a long-term relationship with an organisation while buying a product or a service attributed to the organisation, a brand, or a channel. It is important for organisations to identify those customers who intend to support a long-term relationship with them, seeing as not all customers have the desire to build relationships with organisations (Kinard & Capella 2006:359).

A customer who has no intention to build a relationship possesses transactional intention. Transactional intention refers to a short-term and opportunistic attitude of customers towards an organisation (Kumar et al 2003:669). Indeed, the service encounters between the organisation and customers who have no relationship intention are usually brief and tend to be less intimate (Ward & Dagger 2007:284). Customers possessing transactional intention usually prefer to buy their products and services with less involvement with the organisation (Kinard & Capella 2006:364). Kumar et al (2003:669) explain that transactional customers have low expectations of the services provided by the organisation and are not willing to forgive the occasional service failure, show little affection towards the organisation and can easily switch to competitors. Transactional customers, however, generally constitute a major volume of the income to any organisation. In contrast, customers with a high degree of relationship intention have the willingness to build and maintain relationships with the organisation. These customers are more involved with the products and services of the organisation and express greater intrinsic willingness to maintain relationships with organisations (Kumar et al 2003:669; Varki & Wong 2003:87). Customers who show high involvement do not only have high expectations of the organisation; they are also more concerned about the organisation and its employees (Kumar et al 2003:670). Customers with high relationship intentions have the ability to forgive organisations when a service failure occurred and provide feedback in order to correct the failure (De Coverly, Holme, Keller, Mattison & Toyoki 2002:30; Matilla 2004:137). Finally, customers with a high degree of relationship intention are emotionally attached to the organisation and would feel guilty to consider switching to another organisation (Fullerton 2003:335).

Relationship intention constructs

Kumar et al (2003:670) propose that customers' relationship intentions can be measured by means of five constructs, namely involvement, expectations, forgiveness, feedback and fear of relationship loss.

Involvement

The concept of involvement and the effect it has on customer behaviour have been an expanding area of interest for marketers. However, a lack of consistency in the conceptual and operational definitions of involvement can be detected (Csipak, Chebati & Venkatesan 1995:230). This article focuses on customers' involvement in a relationship with an organisation. This type of involvement can be defined as a person's intention to engage in a relationship activity without any force or obligation (Kumar et al 2003:670). This definition also stresses the degree to which a person would willingly intend to engage in a relationship activity. A customer who is involved with the organisation's product and service will have a greater intention to build a relationship with an organisation (Kumar et al 2003:670; Varki & Wong 2003:89-90). This occurs since organisations are instilling a perceived relational advantage for highly involved customers. Customers' involvements influence their interest in relationships with organisations, as well as their expectations of relational activities initiated by the organisation (Varki & Wong 2003:89-90). Ford (2001:7) supports this view by indicating that customers' involvement in a relationship with an organisation can predict customer expectations about a relationship orientation versus a transaction orientation.

Expectations

Zeithaml, Berry and Parasuraman (1993:2) define customer expectations as predictions made by customers about what is expected to happen during an impending transaction of exchange. Customer expectations are predictors of how the organisation will react or behave, seeing as customer expectations are always concerned with future behaviour (Clow & Beisel 1995:33). Kumar et al (2003:670) therefore argue that a customer who has expectations of an organisation will also be more concerned about the organisation. The more concerned the customer is, the higher the intention to build a relationship with the organisation will be, because the customer cares deeper about the organisation. These customers will also like to see some improvement in the organisation's products and services, implying that customers with higher expectations will be more likely to develop a relationship with an organisation than customers who have no expectations (Kumar et al 2003:670). Customer expectations could therefore be seen as having an impact on relationship intention.

Forgiveness

Robbins and Miller (2004:97) suggest that forgiveness in terms of an organisation-customer relationship can be defined as the willingness of customers to overlook a negative service outcome. Loyal customers are probably more willing to forgive what they perceive as a service failure. A service failure refers to a service encounter that results in a customer being dissatisfied (Gabbott & Hogg 1998:116). Thus, a service failure takes place when the service failed to meet a customer's expectations (La & Kandampully 2004:392). Customers experience negative emotions, including feelings such as anger, discontent, disappointment, self-pity and anxiety when their expectations are not met (Zeithaml, Bitner & Gremler 2006:218). The existence of a trusting relationship might indeed be the granting and acceptance of forgiveness when a service failure occurred. An established relationship between the customer and the organisation may be more resistant to occasional service failures that may allow minor difficulties to be overcome (Marzo-Navarro et al 2004:426). Customers who have formed a long-term relationship with organisations are generally more forgiving even if they have certain expectations about the organisation. Thus, customers will still give the organisation another chance, even if their expectations are not fulfilled. The customer will forgive the organisation, seeing as the relationship is important to the customer. It would seem that customers who show higher forgiveness for service failures would also have a higher intention to form a relationship with an organisation (Kumar et al 2003:670).

Feedback

Clow and Kurtz (2004:142), and Volkov (2004:114) define feedback as the set of all behavioural responses portrayed by customers who involve the communication of negative perceptions relating to a consumption episode and triggered by dissatisfaction with that episode. Therefore, feedback is a result of customers communicating their dissatisfaction or unmet expectations to the organisation.

Most customers who are dissatisfied with a service do not report their dissatisfaction to the organisation (Clark & Baker 2004:45); instead they simply never come back, and worse, may tell friends about the bad experience (Bruhn 2003:70). Organisations are therefore going to increasing lengths to encourage customer feedback in the hope that they are given an opportunity to make amends (Palmer 2005:91). Thus, customers who provide feedback are in a better position to receive service recovery. Service recovery can be defined as the actions taken by an organisation in response to a service failure (Weun, Beatty & Jones 2004:134; Zeithaml et al 2006:214). Thus, service recovery is where the organisation treats displeased customers in such a way that they leave the service experience feeling positively disposed towards the organisation and are also willing to engage with the organisation in future transactions (Mudie & Pirrie 2006:254). Those customers who have benefited from service recovery will be more loyal to the organisation and will also trust the organisation more (Weun et al 2004:133). Feedback from customers could therefore be seen as a factor that has an impact on relationship intention (Kumar et al 2003:670).

Fear of relationship loss

Caruana (2002:256) defines fear of relationship loss as a switching cost that discourages customers from switching to a competitor's product or service. A variety of different switching costs can be identified from literature, but this article will focus on relational switching costs. Caruana (2002:258) defines relational switching costs as the loss of identity and breaking of bonds, consisting of personal relationship loss and brand relationship costs, which can cause psychological or emotional discomfort. Customers who are highly involved with the organisation are emotionally attached to relationships with the employees or the organisation (Fullerton 2003:335). This involvement not only causes customers to feel guilty for leaving, but it also lowers the possibility to switch organisations (Wathne, Biong & Heide 2001:54). This phenomenon occurs because the customer is emotionally attached to either the employees or the brand of the organisation that the customer is in contact with. Thus, customers who fear losing a relationship with an organisation also show high intention to build a relationship with the organisation (Kumar et al 2003:670).

Relationship length

Relationship marketing can be used by organisations as a marketing strategy to keep in touch with customers on a regular basis and to give their customers reasons to maintain a connection with them (Solomon, Bamossy, Askegaard & Hogg 2006:13). Berger and Nasr (1998:19) explain that the length of the relationship between customers and their organisation can determine the value customers provide to the organisation. The value that customers offer will increase as the length of the relationship increases. Therefore, relationships will become more profitable for organisations as the relationship with customers lengthens (Little & Marandi 2003:152).

However, Kumar et al (2003:71) propose that customers' intentions to develop a relationship do not necessarily depend on the length of the relationship with the organisation. Kasper et al (2006:246) support this view by arguing that customers do not offer the same profitability at every moment during their relationship with the organisation. Organisations should therefore be aware that profitability does not always increase as customer relationships lengthen.

PROBLEM STATEMENT AND OBJECTIVES

Identifying customers who have the intention to build long-term relationships can be beneficial for organisations. Kumar et al (2003:670) suggest five constructs to measure relationship intention, namely involvement, expectations, forgiveness, feedback and fear of relationship loss. Even though previous studies in South Africa (De Jager 2006; Mentz 2007) assumed that the five constructs proposed by Kumar et al (2003:670) to measure relationship intention were valid, there remains a need to determine whether the five constructs are valid to measure relationship intention in a South African service setting.

Considering the problem statement and the literature review, the following objectives are set:

• Determine whether the five relationship intention constructs proposed by Kumar et al (2003:670) are valid to measure the relationship intentions of South African banking and life insurance industry customers; and

• Determine the influence of relationship length on the relationship intention constructs.

METHOD

Population and sample

The target population included any person, older than eighteen years, living in Gauteng who uses either banking or life insurance services. This study used a non-probability sampling method, which means some of the elements of the population had little or no chance of being selected for the sample (Cant, Gerber-Nel, Nel & Kotze 2005:53). A convenience sampling method was used to obtain information quickly and inexpensively (Aaker, Kumar & Day 1995:376). In total, 401 respondents participated in the study of which 202 used banking and 199 life insurance services.

Research instrument and data collection

An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used as the research instrument to gather data from customers of leading banking and life insurance organisations in South Africa. The questionnaire proposed by Kumar et al (2003:675) was used as the basis to measure each of the five relationship intention constructs, namely involvement, expectations, forgiveness, feedback and fear of relationship loss. In addition to the 18 items used to measure relationship intention as proposed by Kumar et al (2003:675), 34 additional items were added to the questionnaire to increase the reliability and validity of the relationship intention constructs. The extent to which respondents agreed with the statements that measured relationship intention was tested on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 = yes, a lot to 5 = no, not at all.

Data analysis

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to identify the factors constituting relationship intention. The Oblimin method of rotation was applied (Aaker, Kumar & Day 2003:570-571). Only factor loadings >0.3 were reported, seeing as items with factor loadings < 0.3 do not correlate significantly with the factor (Field 2005:622). Factor scores were calculated as the mean of items contributing to a factor, implying that factor scores can be interpreted on the original measurement scale. Following the factor analysis, respondents were categorised according to the length of their relationship with the organisation in order to determine whether differences exist with regard to the factors identified to measure relationship intention. One-way ANOVAs were performed to determine the statistically significant differences in respondents' intentions to build long-term relationships by considering their relationship length with the organisation. Furthermore, effect sizes using Cohen's d-values were used to indicate practically significant differences between the means of different groups. Bagozzi (1994:248) explains that practical significance measures the strength of the significance of values that enable the researcher to judge the practical importance of an effect or result. The d-values were calculated by using the following formula (Cohen 1988:20-27):

where:

• d = effect size;

•

is the difference between means of compared groups; and

• Smax is the maximum standard deviation of the compared groups.

Effect sizes were interpreted as follows (Cohen 1988:20-27):

• d ≈ 0.2 indicating a small effect with no practical significance;

• d ≈ 0.5 indicating a moderate effect; and

• d ≈ 0.8 or larger, indicating a practically significant effect.

RESULTS

Sample profile

Somewhat more females (58%) participated in the study than males (42%). Respondents' ages varied between 18-25 years (27%), 26-35 years (21%), 36-50 years (30%), 51-65 years (20%), and 66 years and older (2%). Respondents' relationships with their bank or life insurance provider ranged between less than three years (14%), three to five years (18%), six to ten years (19%), 11-15 years (14%), 16-20 years (15%), and more than 20 years (20%).

Factor analysis

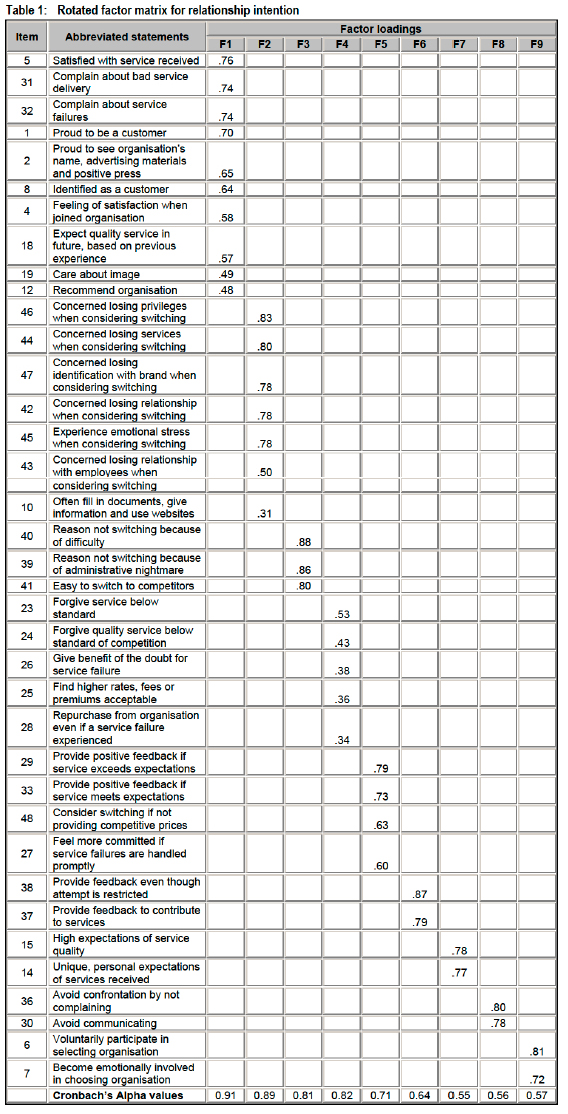

A factor analysis was performed to reduce the dimensionality of data into a smaller set of factors and to uncover the latent structures of the set of variables (Garson 2008:Internet). Table 1 presents the rotated factor matrix for relationship intention.

From Table 1 it can be derived that nine factors were identified to measure respondents' relationship intentions. The nine factors explain 65.92% of the total variance. Of the 48 relationship intention statements used to measure respondents' relationship intentions, 37 items loaded onto the nine factors. Some of the items loaded onto more than one factor. The items that contribute the most to the factors were included. To improve the construct validity of the research instrument, some individual items not loading on any factor were removed from the factor analysis.

The Cronbach's Alpha values for constructs from the factor analysis were calculated to determine the correlation between items in a scale and the total count (Sapsford & Jupp 2006:111&121). Table 1 also shows the Cronbach reliability coefficients, ranging from 0.55 (for factor 7) to 0.914 (for factor 1). The Cronbach's Alpha values in Table 1 of Factors 1 through 5 are > 0.7, indicating that these factors have a relatively high level of reliability between elements in the scale. Although the Cronbach's Alpha values for the last four factors are below 0.7 (0.55 - 0.64), these can still be regarded as acceptable considering the fact that only two items per construct were extracted. Field (2005:668) explains that Cronbach's Alpha values depend on the number of items on the scale. Thus, the factors with Cronbach's Alpha values ranging between 0.55 and 0.64 have a low value, because there are only two items loading on the scale, and not because the scale is unreliable. The following factors loaded onto the five constructs as proposed by Kumar et al (2003:670).

Involvement

Kumar et al (2003:670) identified involvement as a key construct to measure relationship intention. However, the additional items in the questionnaire included to measure involvement revealed that two separate factors loaded onto this construct, namely Factors 1 and 9 (see Table 1). Six of the ten involvement items (Table 1: items 1, 2,4,5,8 and 12) loaded onto Factor 1. Two feedback items (Table 1: items 31 and 32) and two expectations items (Table 1: items 18 and 19) also loaded onto Factor 1, regarded by respondents as related to involvement. The items used to measure this construct related specifically with the respondents' involvement with the organisation. Considering these items, Factor 1 can be labelled as continuing Involvement.

The two items (Table 1: items 6 and 7) that loaded onto Factor 9 also relate to involvement, but more specifically on initial involvement of respondents when choosing their organisation. Factor 9 can therefore be labelled as initial Involvement.

Fear of relationship loss

The items used to measure fear of relationship loss as suggested by Kumar et al (2003:676) loaded onto two separate factors, namely Factor 2 and Factor 3. Six of the ten items (Table 1: items 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 and 47) used to measure fear of relationship loss loaded onto Factor 2. One involvement item (Table 1: item 10) also loaded onto Factor 2. This is regarded as an additional measure of fear of relationship loss by respondents. Factor 2 includes items that relate to the respondents' fear of losing the relationship with the organisation. Considering these items, Factor 2 can be labelled as fear of relationship loss.

Factor 3 included an extra dimension to the construct of fear of relationship loss by including items concerning the difficulty for respondents to switch to the organisation's competitors. The factor analysis revealed that of the ten items used to measure fear of relationship loss, three items (Table 1: items 39, 40 and 41) loaded onto Factor 3. Considering these items, Factor 3 can be labelled as fear associated with switching to competitors.

Forgiveness

This study supports the forgiveness construct as suggested by Kumar et al (2003:670), seeing as all the items used to measure this construct were linked to respondents' forgiveness. Four of the six items (Table 1: items 23, 24, 26 and 28) used to measure forgiveness loaded onto Factor 4. One involvement item (Table 1: item 9) also loaded onto Factor 4. This is regarded as an additional measure of forgiveness by respondents. Considering these elements and the factor loadings of each element, Factor 4 can be labelled as forgiveness.

Feedback

The exploratory factor analysis revealed that the items used to measure the construct feedback, as suggested by Kumar et al (2003:670), were not a uni-dimensional construct. Thus, the measurement of feedback loaded onto three distinct factors, namely Factors 5, 6, and 8. All these factors included elements of feedback. Of the eight items used to measure feedback, two items (Table 1: items 29 and 33) loaded onto Factor 5. Additionally, one fear of relationship loss and one forgiveness item (Table 1: items 27 and 48) also loaded onto Factor 5, regarded by respondents as an additional feedback measure. The items used to measure Factor 5 were related to respondents' response to provide feedback. Thus, Factor 5 is labelled as feedback response.

Factor 6 included elements concerning the feedback respondents provide in order to contribute towards service improvements. Only two items (Table 1: items 37 and 38) loaded onto Factor 6. Considering these items and the factor loading of each item, Factor 6 can be labelled as feedback for improved service delivery.

Of the eight items used to measure feedback, only two items (Table 1: items 30 and 36) loaded onto Factor 8. Factor 8 included elements concerning respondents avoiding contact with the organisation, such as confrontation and communication. Thus, Factor 8 can be labelled as feedback to avoid conflict.

Expectations

This study supports the suggestion by Kumar et al (2003:670), considering that all the items used to measure expectations were related to respondents' expectations of services from the organisations. Four expectations items were included in the research instrument. Of these, two items (Table 1: items 14 and 15) loaded onto Factor 7. Thus, Factor 7 is labelled as expectations.

Association of relationship length with factor scores

One-way ANOVAs were performed to determine whether statistically significant differences exist between respondents with different lengths with their bank or life insurance provider in terms of the nine identified factors. An initial analysis found that statistically significant differences exist between respondents' relationship lengths for only three of the nine factors, namely Factor 3 (fear associated with switching to competitors), Factor 7 (expectations), and Factor 9 (initial involvement). It was therefore decided to determine the practical significance for these three factors.

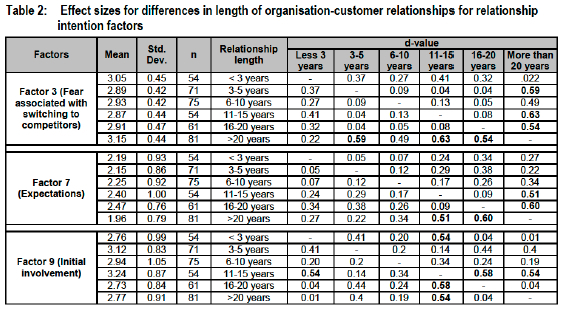

Table 2 indicates the results for effect sizes when comparing the length of respondents' relationships with their bank or life insurance provider in terms of Factors 3, 7 and 9.

Table 2 illustrates that nearly all the d-values display moderate and small effect sizes. Moderate-sized d-values for Factor 3 (fear associated with switching to competitors) were found when comparing respondents with a relationship length between three to five years (d = 0.59), 11-15 years (d = 0.63) and 16-20 years (d = 0.54) with those with a relationship length of >20 years. The mean scores indicate that respondents from all the relationship lengths were neutral with regard to the statements comprising Factor 3.

From Table 2 it can furthermore be observed that there are moderate practically significant differences in effect sizes when comparing respondents with different relationship lengths in terms of Factor 7 (expectations). Moderate-sized d-values for expectations were found when comparing respondents with a relationship length between 11-15 years (d = 0.51) and 16-20 years (d = 0.60) with those with a relationship length >20 years. The mean scores indicate that respondents from all the relationship lengths mostly agreed with the statements comprising Factor 7.

Moderate practically significant d-values were identified when comparing respondents with different relationship lengths in terms of Factor 9 (initial involvement). As illustrated in Table 2, respondents with a relationship length between 11-15 years differed from respondents with a relationship length between 16-20 years (d = 0.58); respondents with a relationship length of more than 20 years (d = 0.54); as well as respondents with a relationship length of less than three years (d = 0.54). The mean scores indicate that respondents with short- and long-term relationship lengths agreed more with the statements comprising Factor 9, than those respondents with medium relationship lengths.

Considering the above findings, it can be concluded that statistically significant differences were found for only three factors when comparing respondents with different lengths with their service providers on the nine identified relationship intention factors. Despite the statistical significance, no practically significant differences were found between respondents' view of the nine factors and any relationship length.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Relationship intention

Relationship intention enables organisations to identify potential customers who intend to form a long-term relationship with the organisation. It makes sense to invest in building relationships with customers with high relationship intentions as long-term relationships with these customers will ensure that the organisation sustains its profitability in the long run. However, it is difficult to understand the nature of relationship intention without understanding the constructs used to measure relationship intention. Kumar et al (2003:670) propose involvement, expectations, forgiveness, feedback and fear of relationship loss to measure relationship intention. However, this study identified nine factors (see Table 1) to measure relationship intention, namely continuing involvement, fear of relationship loss, fear associated with switching to competitors, forgiveness, feedback response, feedback for improved service delivery, expectations, feedback to avoid conflict, and initial involvement. Thus, these results do not only confirm the five constructs proposed by Kumar et al (2003:670), but also identified four additional factors that support the five constructs. Thus, these results highlight the need to consider more factors than the five constructs identified by Kumar et al (2003), when measuring relationship intention. It is therefore suggested that when measuring relationship intention, the following factors be considered: to measure involvement, two sub-constructs need to be measured, namely continuing involvement and initial involvement. To measure fear of relationship loss, two sub-constructs need to be measured, namely fear of relationship loss and fear associated with switching to competitors. The construct forgiveness can be measured, as suggested by Kumar et al (2003:670), without considering any additional sub-constructs. To measure feedback, three sub-constructs need to be measured, namely feedback in terms of responding to the organisation, feedback for improved service delivery and feedback to avoid conflict. The construct expectations can be measured, as suggested by Kumar et al (2003:670), without considering any additional sub-constructs.

This research has helped to validate and augment the five constructs suggested by Kumar et al (2003:670) to measure relationship intentions. The implication of these findings is that organisations like banks and life insurance providers should measure their customers' intentions to form a relationship and identify those with whom long-term relationships should be built. Banks and insurance providers can use the current findings to measure their customers' relationship intentions, thus helping to segment customers according to their relationship preference, as money and resources should not be wasted on developing relationships with customers who have no intention to build long-term relationships with the organisation. It can therefore be recommended that banks and life insurance organisations should identify the relationship intention of their customers to ensure that relationships are built with those customers who wish to form a relationship with the organisation.

Length of relationship

Relationships between organisations and customers become more profitable as the relationship lengthens (Little & Marandi 2003:152). Relationship length can therefore be a good indicator of a customer's willingness to build a long-term relationship with an organisation. However, this study found that statistically significant differences exist for respondents' relationship lengths with their bank or life insurance provider for only three of the nine identified factors. Also, for these three factors, no practically significant differences were found between respondents' relationship lengths and their views of the factors. Thus, relationship length is not a good indicator for relationship intention. Organisations should therefore not automatically assume that customers who have been with the organisation for a long period of time have the intentions to build long-term relationships.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

It is important to recognise the limitations of this study. This study was restricted to only two service settings, namely banking and life insurance. The results can thus not be generalised to all service types. Replication in different service contexts would provide greater confidence to generalise the current results. A non-probability sampling method was used for this study. The results were, therefore, not representative of the population, but only representative of those respondents who participated in the study. An opportunity for future research could be to use a probability sampling method. Using a probability sampling method would make the results representative of the whole of the population.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AAKER D.A., KUMAR V. & DAY G.S. 1995. Marketing research. 5th ed. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

AAKER D.A., KUMAR V. & DAY G.S. 2003. Marketing research. 8th ed. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

ALEXANDER N. & COLGATE M. 2000. Retail financial services: transaction to relationship marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 34(8):938-953. [ Links ]

ANDERSON J.L., JOLLY L.D. & FAIRHURST A.E. 2007. Customer relationship management in retailing: a content analysis of retail trade journals. Journal of Retailing and Consumer services, 14:394-399. [ Links ]

BAGOZZI R.P. (ed). 1994. Principles of marketing research. Cambridge: Blackwell. [ Links ]

BERGER P.D. & NASR N.I. 1998. Customer lifetime value: marketing models and applications. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 12(1):17-30. [ Links ]

BERRY L.L. 1983. Relationship marketing: emerging perspectives in service marketing. Chicago, Illinois: America Marketing Association. [ Links ]

BRUHN M. 2003. Relationship marketing. London: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

CANT M., GERBER-NEL C., NEL D. & KOTZE T. 2005. Marketing research. 2nd ed. Claremont: New Africa. [ Links ]

CARUANA A. 2002. Service Loyalty: the effects of service quality and the mediating role of customer satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing, 36(7/8):811-829. [ Links ]

CLARK M. & BAKER S. 2004. Business success through service excellence. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

CLAYCOMB C. & MARTIN C.L. 2002. Building customer relationships: an inventory of organisations' objectives and practices. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(7):615-635. [ Links ]

CLOW K.E. & BEISEL J.L. 1995. Managing customer expectations of low-margin, high-volume services. Journal of Services Marketing, 9(1):33-46. [ Links ]

CLOW K.E. & KURTZ D.L. 2004. Services marketing: operation, management, and strategy. 2nd ed. Cincinnati, Ohio: Atomic Dog. [ Links ]

COHEN J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, Michigan: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

CSIPAK J.J., CHEBATI J.C. & VENKATESAN V. 1995. Channel structure, customer involvement and perceived service quality: an empirical study of the distribution of a service. Journal of Marketing Management, 11(1-3): 227-241. [ Links ]

DE COVERLY E., HOLME N.O., KELLER A.G., MATTISON T.F.H. & TOYOKI S. 2002. Service recovery in the airline industry: is it as simple as 'failed, recovered, satisfied'? Marketing Review, 3(1):21-38. [ Links ]

DE JAGER J.N.W. 2006. Relationship intention as a prerequisite for relationship marketing: an application on short-term insurance customers. Potchefstroom: North-West University. (Dissertation - MCom). [ Links ]

EGAN J. 2004. Relationship marketing: exploring relational strategies in marketing. 2nd ed. Harlow: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

FIELD A. 2005. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 2nd ed. London: Sage. [ Links ]

FORD W.S.Z. 2001. Customer expectations for interactions with organizations: relationship versus encounter orientation and personalized service communication. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 29(1):1-28. [ Links ]

FULLERTON G. 2003. When does commitment lead to loyalty? Journal of Service Research, 5(4):333-344. [ Links ]

GABBOTT M. & HOGG G. 1998. Consumers and services. Chichester: Wiley. [ Links ]

GARSON G.D. 2008. Factor analysis. Available from: www.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/pa765/factor.htm; Downloaded on 2008-02-13. [ Links ]

GRÖNROOS C. 1994. From marketing mix to relationship marketing: towards a paradigm shift in marketing. Management Decision, 32(2):4-20. [ Links ]

GRÖNROOS C. 2000. Service management and marketing: a customer relationship management approach. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley. [ Links ]

GRÖNROOS C. 2007. Service management and marketing: customer management in service competition. 3rd ed. Chichester: Wiley. [ Links ]

KASPER H., VAN HELSDINGEN P. & GABBOTT M. 2006. Services marketing management: a strategic perspective. 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley [ Links ]

KINARD B.R. & CAPELLA M.L. 2006. Relationship marketing: the influence of consumer involvement on perceived service benefits. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(6):359-368. [ Links ]

KUMAR V., BOHLING R. & LADDA R.N. 2003. Antecedents and consequences of relationship intention: implications for transaction and relationship marketing. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(8):667-676. [ Links ]

LA K.V .& KANDAMPULLY J. 2004. Market oriented learning and customer value enhancement through service recovery management. Managing Service Quality, 14(5):390-401. [ Links ]

LITTLE E. & MARANDI E. 2003. Relationship marketing management. London: Thomson. [ Links ]

MARZO-NAVARRO M., PEDRAJA-IGLESIAS M. & RIVERA-TORRES M. 2004. The benefits of relationship marketing for the consumer and for the fashion retailers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 8(4):425-436. [ Links ]

MATILLA A.S. 2004. The impact of service failures on customer loyalty: the moderating role of affective commitment. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(2):134-149. [ Links ]

MEHTA S.C. & TAMBE H. 1997. Relationship concept and customer services: a case study of corporate banking. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 4(2):129-134. [ Links ]

MENTZ M.H. 2007. Verhoudingsvoorneme van klante in die Suid-Afrikaanse motorbedryf. (Relationship intention of customers in the South African motor vehicle industry). Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. (Dissertation - MCom). [ Links ]

MUDIE P. & PIRRIE A. 2006. Services marketing management. 3rd ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

PALMER A. 2005. Principles of services marketing. 4th ed. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

ROBBINS T.L. & MILLER J.L. 2004. Considering customer loyalty in developing service recovery strategies. Journal of Organisation Strategies, 21(2):95-109. [ Links ]

SAPSFORD R. & JUPP V. (eds). 2006. Data collection and analysis. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

SOLOMON M., BAMOSSY G., ASKEGAARD S. & HOGG M.K. 2006. Consumer behaviour. 3rd ed. Harlow: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

VARKI S. & WONG S. 2003. Customer involvement in relationships marketing of services. Journal of Service Research, 6(1):83-91. [ Links ]

VOLKOV M. 2004. Successful relationship marketing: understanding the importance of complaints in a customer-oriented paradigm. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 2004(1):113-123. [ Links ]

WARD T. & DAGGER T.S. 2007. The complexity of relationship marketing for service customers. Journal of Service Marketing, 21(4):281-290. [ Links ]

WATHNE K.H., BIONG H. & HEIDE J.B. 2001. Choice of supplier in embedded markets: relationship and marketing program effects. Journal of Marketing, 65:54-66. [ Links ]

WEUN S., BEATTY S.E. & JONES M.A. 2004. The impact of service failure severity on service recovery evaluations and post-recovery relationships. Journal of Services Marketing, 18(2):133-146. [ Links ]

WONG A. & SOHAL A.S. 2006. Understanding the quality of relationships in consumer services: a study in a retail environment. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 23(3):244-264. [ Links ]

ZEITHAML V.A., BERRY L.L. & PARASURAMAN A. 1993. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21 (1):1-12. [ Links ]

ZEITHAML V.A., BITNER M.J. & GREMLER D.D. 2006. Services marketing: integrating customer focus across the firm. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

ZOLKIEWSKI J. 2004. Relationships are not ubiquitous in marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 38(1/2): 24-29. [ Links ]