Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Staff retention factors affecting the contact centre industry in South Africa

F L Kgomo; I Swarts

Department of People Management and Development, Tshwane University of Technology

ABSTRACT

Retention of employees has historically been a concern cause for among managers in the contact centre industry. While staff turnover disrupts production schedules, it is also costly as new workers with appropriate skills sets need to be recruited, trained and brought up to speed. This can have serious consequences when skilled workers leave, particularly during periods of heightened competition and tight labour markets. The main purpose of this paper was to determine retention factors affecting the contact centre industry in South Africa. A survey was conducted among the total population of 386 and responses were received from 16 contact centres nationwide. The study employed descriptive, inferential statistical procedures and analytical induction to analyse the quantitative and qualitative data. The findings suggested that 85.12% of the participants expressed the intention to leave the industry. This implies that retention is cardinal factor that needs to be addressed in the contact centre industry.

Key phrases: Retention, labour turnover, management style, job satisfaction, employee engagement.

INTRODUCTION

Retaining employees is critical in today's business environment. Research by Ernst and Young shows that attracting and retaining employees are two of the eight most important issues investors take into account when judging the value of a company (Michlitsch 2000). However, Abbasi and Holman (2000) identify employee turnover as a factor that often jeopardizes an organisational objectives. Employee turnover results in expenses related to employee replacement as well as entailing many hidden costs and consequences. Regarding the financial implications, Taylor (2002) identifies high employee turnover as one of the most costly problems that companies face. Losing an employee can cost a company as much as eighteen (18) months salary for professional and six (6) months salary for an hourly employee (Thornton 2001). Another estimate puts the cost at 25% of the employee's annual salary plus 25% of the benefits package offered (Amig & Jardine 2001). In addition to the financial loss incurred by employee turnover, other losses include declining productivity, lower employee morale and disrupted customer relations (Abbasi & Hollman 2000), as well as loss of employee expertise and institutional knowledge (Mitchell, Holton & Lee 2001). In today's competitive business environment, it is imperative that companies focus on retention, gain commitment from their employees, and manage employee turnover (Galunic & Anderson 2000). The purpose of this paper is to examine employee retention and more specifically those work factors in the contact centre industry that are important in determining an employee's intention to stay or leave.

RETENTION

Generally, an employee's decision to resign from a company is a complex process because factors, called turnover drivers, create an environment that is no longer acceptable to the employee (Oh 2001:13). Numerous surveys that have been conducted to determine the influence of employee turnover, have produced results varied. Some factors identified as affecting turnover include organisational culture (Sherindan 1992:1036), supervisory relationships (Tepper 2000:181), compensation (Burgess 1998:55), and work environment (Guthrie 2001:190; Blum, Gilson & Shalley 2000:223).

Organisational culture, defined as the cornerstone values, beliefs, norms, standards and assumptions concerning work that members of an organisation share, has a potent effect on the motivation of employees to continue working for their employers (Mainiero 1993:84). Sheridan (1992:1043) who observes that an organisation's cultural values have in effect on all interactions with employees also notes that other researchers argue that the fit between an organisation and an employee is important to retention. Furthermore, individuals are attracted to certain organisations. However, when they do not fit into an organisation, they leave. Autry and Daugherty (2003:175) report a relationship between personal organisational fit, job satisfaction and intent to stay. In a time where reasonable pay and benefits are expected, an organisation's culture can be the deciding factor in an employee's decision to remain with his or her employer.

Another factor that influences an employee's decision to stay is the relationships employees establish with their superiors and colleagues. Studies show that managers and supervisors can have a significant impact on employee turnover. A Gallup organisation study reports that the length of an employee's stay is determined largely by his relationship with managers (Dobbs 2001:57). Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski and Roades (2002:565) maintain supervisor support correlates with an employee's intention to stay. Taylor (2002:37) notes that employees want leaders who know them, understand them, treat them fairly and are supervisors that they can trust. Another study indicates subordinates whose supervisors are more abusive report higher turnover, less favourable attitudes towards the job, life and the organisation, leading to greater conflict between work and family life, and causing greater psychological distress (Tepper 2000:179). Also, as many of today's organisations have a diverse workforce, supervisory relationships with employees are extremely important for retention. According to a survey conducted by Alignment Strategies, quality supervisory relationships are significant in bonding young (age 21-30) and culturally diverse employees to their organisations (Dixon-Kheir 2005:139).

Poorly designed wage policies in which salaries and benefits are not competitive can lead to staff turnover, because studies show that turnover is higher in organisations with lower compensation (Burgess 1998:55). Traditionally, raises and promotions are the incentives offered to workers to stem the rate of turnover. Benefits that meet an employee's individual needs are becoming more important (Withers 2001:36). Additionally, soft benefits, such as flexitime, have helped many organisations to ensure employee commitment (Ulrich 1998:12).

The work environment also affects employees. According to Borstorff and Marker (2007:17), in a survey among 2 200 individual employees with a favourable work environment have higher job satisfaction and lower intention to leave. Factors that enhance job satisfaction include job autonomy, challenge, control, importance and encouragement from supervisors. On the other hand, factors that diminish job satisfaction include the existence of rigid procedures, use of surveillance, lack of resource, and restricted control overwork procedures (Blum et al 2000:216). Mitchell et al (2001:98) maintain that being asked to do something against one's beliefs, observing unfair employment practices, having a major disagreement with a senior, employee discomfort with the company culture and a sense of not belonging correlate with intent to leave. Longenecker and Scazzero (2003:59) further assert that intent to leave often correlates with a better job opportunity elsewhere, more money, a bad supervisor, lack of appreciation, or an inability to get time off from work. Additionally, over the past twelve years, employees have increasingly focused on personal growth and happiness and less on how they are defined by organisational affiliation. Younger generation employees tend to identify with their formal title and nature of work. They do not commit themselves to the organisation, but rather focus themselves (Jurkiewicz 2000:55).

The fastest growing segment of employees regard those who are 55 years and older, as having different work. This new workforce requires managers who lead therefore they respond to being asked, not being told. They want the opportunity to showcase talents and be involved in the decision-making process of the organisation (Abbasi & Holman 2000:333).

It is important to appreciate which work issues are important to employees. Research results vary on what employees identify as important for continuing their employment. According to Borstorff and Marker (2007:18), more than 500 000 employees in 300 companies indicate that, of 50 retention factors, pay is the least important. Extensive research done at hundreds of companies by the Corporate Leadership Council reveal that base pay, manager quality and health benefits are most important to employees (Burleigh, Eisenberg, Kilduff & Wilson 2001). Lord (2002:3) identify good supervision, family/work balance, benefits and pay as motivating factors across all age groups.

RESEARCH QUESTION

The purpose of this paper was to determine retention factors affecting contact centre industry in South Africa. To achieve this purpose, the following research questions formed the basis of data gathering, data analysis and data interpretation:

• Is retention an issue in the contact centre industry?

• Is there a relationship between employee engagement and retention?

• Are there biographical differences between the employees that have an intention to leave the organisation and those who have no intention to leave the organisation?

• Which factors relating to work and the organisation are critical to ensuring retention?

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Participants

Data were collected from a questionnaire administered to contact centre staff. As a self-administered questionnaire, eight separate existing instruments were combined and pretested. The questionnaire was couriered to 16 contact centres in eight provinces, excluding North West. Non-probability sampling was used for the study through a combination of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. It can thus been seen that although the researcher relied on such participants as were available (convenience sampling), a very specific type of person was appointed for the study. This implies that the sampling approach was also purposive in nature (Rossouw 2003:113). Bless and Higson-Smith (2000:92) argues that purposive sampling is valuable, especially if an expert who knows the population to be studied is involved. In this study all lead persons were contact centre coaches or supervisors in their respective domains. They helped the researcher to select subjects, as they knew the contact centre staff members. The researcher is of the opinion that through this technique the sample was more representative, as all cases being brought to the researcher's attention were included.

Procedure

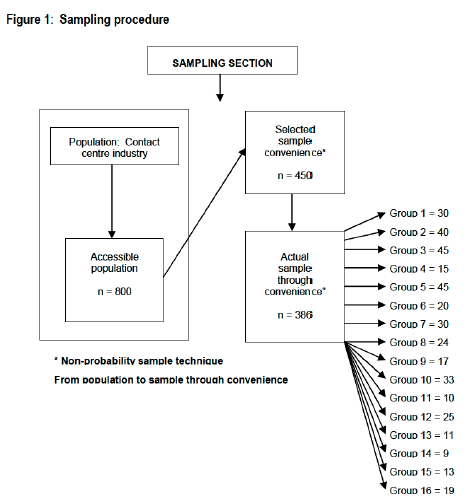

Immediately after permission had been granted by the four participating companies, the questionnaires were couriered to a lead contact person appointed by the contact centre managers at each of 16 contact centres nationwide. The lead contact persons were coaches in their respective contact centres. The lead contact persons' responsibilities were to distribute and collect the questionnaires. The lead person was requested to courier the questionnaires back to the researcher. Weekly telephone calls were made to the lead persons. Administration of the returned questionnaires included data coding and editing, data entry, data cleaning and data-processing. The procedure followed to draw the sample is depicted in Figure 1.

Measuring instrument

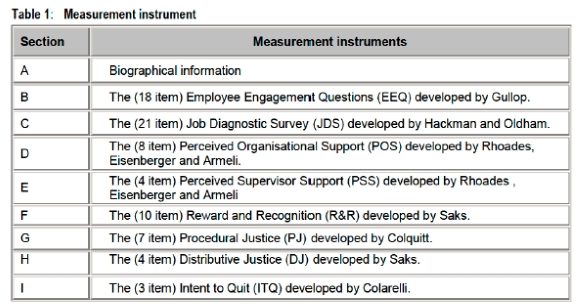

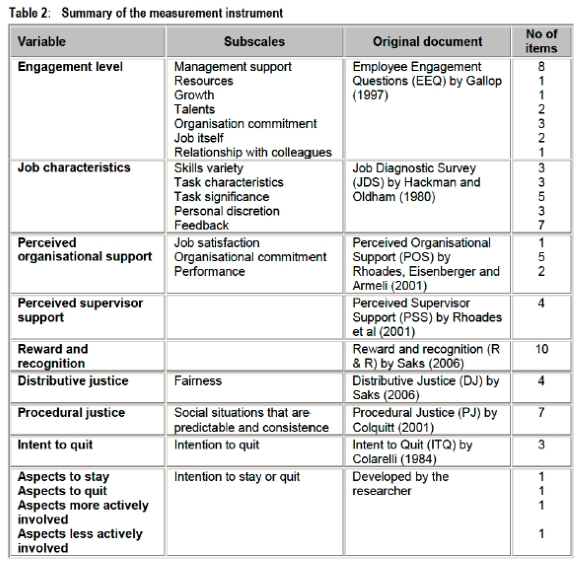

In a self-administered questionnaire, eight separate existing instruments were combined and pre-tested. The questionnaire was couriered to 16 contact centres in eight provinces, excluding North West. After the questionnaires had been completed, they were couriered back to the researcher. A biographical-characteristic section was inserted the questionnaire. To avoid confusion among the respondents, different instruments were separated into sections, as depicted in Table 1.

In line with the advice by Leedy and Ormrod (2005:191), clear instructions were given at the beginning of each section as well as clear explanations on the interpretation of the measurement scales. Each questionnaire was accompanied by a covering letter explaining the purpose of the study the importance of completing the questionnaire, the confidentiality agreement and general instructions on how to complete the questionnaire.

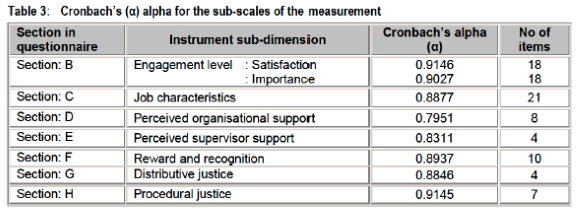

The researcher relied on Cronbach's alpha (a) coefficient to ensure the internal consistency of the questionnaire. The internal consistency reliability coefficients of the study were measured on all seven sub-dimensions, excluding section A (Biographical information) and section I (Intent to quit), the open-ended question. This information is depicted in Table 3. The information align with criteria of alpha ranging from .7951 (Perceived organisational support) to the highest .9146 (Engagement level). These coefficient alphas show that the reliability of the measurement instrument is good.

The above a is in line with the results from the research conducted by Saks (2006:608), measuring job and organisation engagement. The job engagement scale resulted in α = 0.82 and the organisation items loaded yielded α = 0.90.

The second part was semi-structured, with open-ended questions to allow the respondent to express his or her own responses to the questions. This enabled the researcher to extract textual material. The following four open-ended questions were included:

• Which aspects of your job or contact centre will make you stay with your current organisation?

• Which aspects of your job or contact centre will make you quit your job at your current organisation?

• Which aspects of your job will make you become more actively involved in your job and the organisation?

• Which aspects of your job will make you become less actively involved your job and the organisation?

Data analysis

As mentioned, the pre-structured questionnaire consisting of closed questions (numerical data) and open-ended questions (textual data). The two sets of data required different methods of analysis.

Numerical data analysis

Bless and Higson-Smith (2000:156) refers to statistics as a numerical value that summarises some characteristics of the sample. For the purpose of this study, the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) was used for the analysis of all the numerical data. The following data analysis techniques were employed:

• Pearson's chi-square test to measure the strength of the relationships between the various variable and constructs included in the study;

• Reliability (Cronbach's alpha coefficient) to measure the internal consistency of the questionnaire;

• Descriptive measurement to describe the data and the sample;

• Factor analysis to determine the general dimensions or factors that exist within the data set;

• Logistical regression to identify specific factors of engagement that can predict the intention to leave; and

• Analytical induction to establish additional factors on qualitative data.

Textual data analysis

The purpose of conducting a qualitative study is to produce findings. Patton (2002:432) states that qualitative analysis transforms data into findings. From a qualitative measurement, the answers to four open-ended questions were analysed by identifying general themes through content analysis. The purpose was to concentrate on the central themes that were extracted. Final analysis was done by comparing material on the extracted themes to look for variations in meaning and establish connections between the themes. For this process the approach of Marshall and Rossman in De Vos (1998:342-343) was used.

RESULTS

The results are presented in the order of the research questions.

• Is retention an issue in the contact centre industry?

The researcher posed three questions to the participants in the measurement instrument related to their intention to stay or leave (retention):

(1) I frequently think of leaving my job;

(2) I am planning to look for a new job during the next 12 months;

(3) If I have my own way, I will be working for this organisation one year from now.

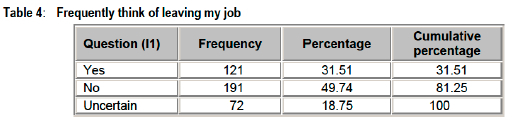

Table 4 indicates that 31.51% of respondents voiced an intention to leave.

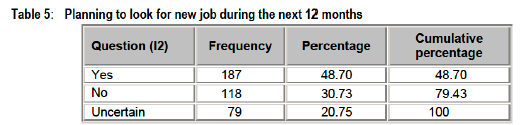

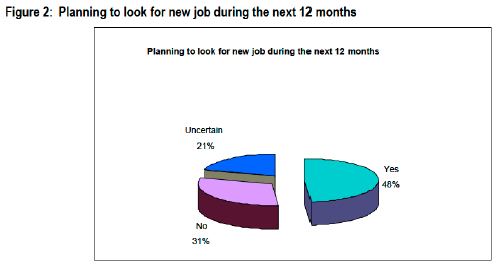

Table 5 and Figure 2 show that 48.70% of the respondents affirm that they plan to look for a new job during the next 12 months, 30.73% are not planning to look for new jobs during the following 12 months, while 20.75% were uncertain.

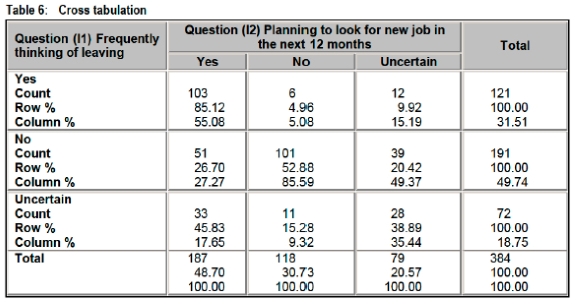

The cross-tabulation in Table 6 indicates an association between 'frequently thinking of leaving the job 'and 'planning to look for a new job in the next 12 months'.

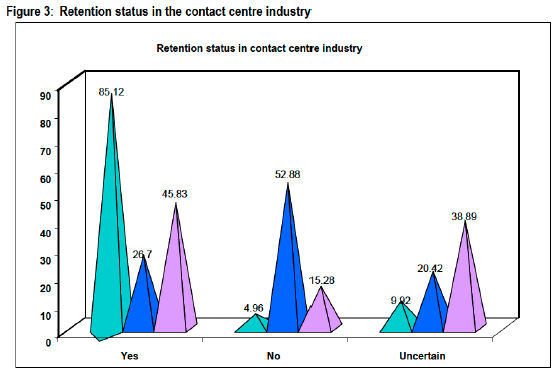

Table 6 shows that 85.12% (n = 103) are planning to look for a new job while frequently think of leaving. Of those who do not frequently think of leaving, 26.70% (n = 51) plan to look for a new job. Figure 3 illustrates the retention status in the contact centre industry.

From profiling the intention of respondents (Figure 3), it is clear that the majority of the respondents intend to leave (85.12%), with a further 4.96% of respondents planning to look for a new job during the next 12 months, while 9.92% were uncertain. This implies that retention is an important factor to be addressed in the contact centre industry.

Of the respondents who showed less interest in leaving the contact centre industry (26.70%), 52.88% were not planning on looking for a new job in the next 12 months and 20.42% were uncertain about their position.

The percentages for the intentions to leave or stay in the study are aligned with the research conducted by Lee (2008:5), showing that on average, contact centres lose 33 to 61% of their agents annually. The larger the contact centre, the greater the agent turnover. In the study conducted by Gallagher (2004), turnover rates as high as 40% are reported for contact centre agents in insurance organisations in America. Even in high-quality contact centres, attrition remains high (Kleemann & Matuschek 2002:4). In 1999, attrition ranged from 15% and 50% per year in German contact centres (Kleemann & Matuschek 2002:3). A benchmark study in 1998 by Purdue University (Call Centre News Service 1999:4) found that attrition rates varied between full and part-time agents and between inbound and outbound agents. They present the following findings: part-time, inbound = 33.6%, full-time, inbound = 26.0%, part-time, outbound 35.5% and full-time, outbound = 21.3%. As the findings of this study indicate unacceptably high levels of attrition in the South African industry, a red light is flashing for the South African contact centre industry to investigate the phenomenon thoroughly and to take proactive measures. Attrition can be the result of employees leaving, being dismissed or retiring. There seems to be truth in the claim that attrition rates are higher among part-time contact centre employees. Taking into account that most South African contact centre employ part-time staff, South African contact centres are faced with an even greater challenge to counter attrition successfully.

• Is there a relationship between employee engagement and retention?

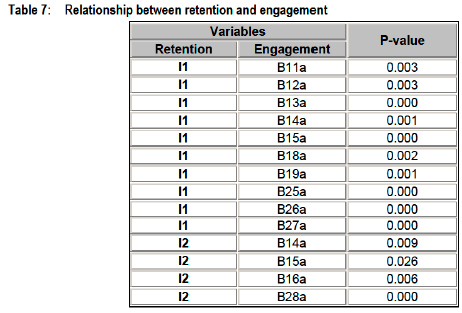

This question sought to establish the relationship between retention and engagement on significant variables. The relationship will be statistically analysed using Pearson's Chi-square and judged in terms of the p-value. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicates that the two categorical variables are statistically dependent, that is, an association between the two variables exists. The p-values illustrated in Table 7 indicate whether significant differences exist between the categories for each variable.

Pearson's Chi-square was used to predict the association between retention and engagement. As the p-values are less than 5% (all p-values are less than 0.05) the relationship between retention and employee engagement is significant. For example: variable 11 (I frequently think of leaving my job) and variable B11a ("I know how my supervisor wants me to do my job"); In these two variables the relationship is found to be significant with a p-value = 0.003.

Another example: variable 11 (I frequently think of leaving my job) and variable B19a ("In my job, my supervisor listens to, and encourages me to share my opinions") shows a p-value of 0.001, which indicates a significant relationship between retention and engagement. Based on the results in Table 7, it appears that in order to retain employees, they must be fully engaged in their daily activities.

The findings of this study correlate strongly with the literature. According to Frank (2004), employee retention and employee engagement are joined at the hip and represents two major human resource challenges as we move further into the 21st century. Beverly and Phillip (2006) state that employee engagement has been shown to have a statistical relationship with productivity, profitability, employee retention, safety and customer satisfaction. Engagement has been extensively linked to the organisational environment (Schaufeli & Salanova 2007:178). Strong relationships between engaged employees and positive effects have been identified (Harter, Schmidt & Hayes 2002). Additionally, the negative effects of employees not being engaged in their jobs are well documented in the literature (Schaufeli & Salanova 2007:180). It has been empirically confirmed that a relationship exists between these two concepts. The contact centre industry should start engaging their employees fully to reduce attrition levels.

• Are there biographical differences between the employees that have an intention to leave the organisation and those who have no intention to leave the organisation?

Pearson's Chi-square was used to determine if any biographical differences existed between employees who had an intention to leave and those who had no intention to leave. The relationship will be judged in terms of the p-value. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicates that the two categorical variables are statistically dependent, that is, an association between the two variables exists.

In the results, 52.63% of females frequently think of leaving their jobs, while the males report a rate of 41.61%. This implies that females, as the preferred gender employed in contact centres, will also have a great impact when leaving. The companies lose skills as well as the investment made to develop these agents. The results also indicate that of the employees between the ages of 30 and 39, 54.95% frequently think of leaving their job. The second age category with a higher intention to leave is 40 to 49-year-olds, followed by the youth ranging from 18 to 29, with 48.29%. This means that companies lose experience, flexibility and skills, as the youth are more flexible and energetic, while those in the middle-aged category are more experienced and skilled. The consequences will be felt more by the organisation and its clientele. The organisations with employees that indicate the highest intention to leave are telemarketing and health services, with 55.56%. As these organisations have to deal with outbound calls, this confirms the results of A8 (The type of contact centres with the most employees who frequently think of leaving their jobs are the outbound one). This implies that outbound contact centres are faced with the serious problem of losing their staff and incurring the high costs of recruiting and training new staff members. Job status indicates that agents, coaches and team leaders also score high with intention to leave. This means that the daily operations of contact centres will be affected. Productivity will decline, the satisfaction of clientele will be affected negatively, managers will have continuous stress and these organisations will lose revenue. The results also indicate that temporary staff frequently thinks of leaving, with 49.16%. This implies that investing in a large number of temporary staff will have a detrimental impact on the organisation in the long run.

The findings of this study correlate well with that in the literature. Belt, Richardson and Webster (2002:20) find that contact centres admit to recruiting women on the assumption that they are better at performing emotional functions. Women make up approximately 70% of the work force in the contact centre industry (Batt 2002:590). The results show that 49.16% of temporary staff frequently thinks of leaving. Benner's (2006:1036) research indicates that employment conditions in South African contact centres appear to be somewhat less favourable. A large proportion of contact centre employees are hired through temporary recruitment agencies. In this study, employees of outbound contact centres indicate a high rate of intention to leave. Garavan, Wilson, Cross & Carbery (2008:612) state that work in outbound contact centres tends to be more stressful due to the high performance standards demanded. They further point out that if employees leave, this reduces the value of the investment that the company has made and may discourage extended induction and comprehensive training and development programmes (Garavan et al 2008:612).

The Call Centre Association (CCA) Research Institute warns that "given the requirements for organisations to gain returns from their investment in staff, and the rising demand of customers, this factor alone challenges the contact centre industry with one of its most daunting problems (CCA Research Institute 2001:46). Mobley, Griffeth, Hand and Meglino (1979:495) note that the relationship between intentions and turnover is consistent and generally stronger than the satisfaction-turnover relationship, although it still accounts for less than a quarter of the variability in turnover. The results indicate that agents have a high rate of intention to leave. The literature confirms this by stating that contact centres tend to be characterised by a flat structure where as the majority of employees occupy agent positions. There are relatively few groups of team leaders or supervisors and contact centre managers (Houlihan 2004:217). This factor exacerbates agent turnover.

• Which factors of the work and organisation are seen as critical to facilitating retention?

Factor analysis was used to determine which factors of work and organisation are seen as critical to facilitating retention in the contact centre industry. The results present two dimensions regarding the critical factors of retention: management support and organisational commitment.

MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

Supervisors: 71% of participants are dissatisfied with their supervisors as they do not regard them as people. This implies that management skills are vital to supervisors. Encouragement: 68% of respondents are dissatisfied with the level of encouragement they receive from their supervisors. This implies that in-depth training on interpersonal relations should be provided to supervisors. Feedback: 71% of participants are dissatisfied with the lack of feedback on progress made in the short term and long term. This means that employees require feedback on all avenues of their job. Leadership style: 67% of participants are not satisfied with the leadership style. Competence of leaders: 68% of participants are dissatisfied with the level of competence of their leaders.

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT

Resources: 65% of participants are dissatisfied with resources in their organizations. Recognition: 78% of participants are not satisfied with recognition or praise they receive. This implies that they do not see any purpose in doing their job effectively or even going extra mile because no one notices. Type of assessment: 79%of respondents are not satisfied with the type of assessment they receive. This implies that assessment process need to be revised and the procedures of feedback made known to all staff members. Company as place of work: 72% of participants are dissatisfied with their companies as places of work. This could mean that the logistics of the contact centre including both ergonomics and staffing strategy should be addressed to boost morale.

The findings of this study correlate well with literature. Vazirani (2007:7) identifies the following factors as critical to facilitating retention; career development or opportunities for personal development, effective management of talent, clarity of company values, respectful treatment of employees, company standards of ethical behaviour, empowerment, image and other factors such as equal opportunities and fair treatment, performance appraisal, pay and benefits, health and safety, job satisfaction, communication and co-operation.

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this research article was to identify the retention factors affecting contact centre industry in South Africa. Being aware of the identified reasons for agents turnover will assist contact centre managers obviate problems and to retain their staff. Ten retention factors that would be used to solve the high labour turn over problem in the industry, have been identified. These factors could be guidelines and used as a quality control mechanism by the South African contact centre industry to address the issue of retention.

Advancement opportunities: This component explores issues such as internal growth opportunities, the potential for advancement, the importance of career development and the relationship between job performance and career development. This component sets out to examine whether the employee believes that he/she has a chance to grow within the organisation. Studies show that a lack of advancement opportunities is the main reason that employees leave an organisation.

Recognition: Employees who feel they are being listened to and recognised for their contributions are likely to be more engaged. People like to be recognised for their unique contributions. According to Wellins, Bernthal and Phelps (2007:15), recognition for employees emerges as one of the most important factors influencing employee commitment to their employers. Studies also show that employees who receive regular recognition and praise are more likely to raise their individual productivity levels, increase engagement with their colleagues and remain with the organisation for longer.

Compensation packages: This component focuses in detail on how employees feel regarding their compensation and benefits. Contact centre agents need to receive compensation packages that they perceive to be in line with their expectations and to enable them to maintain the same or a better standard of living.

Staffing strategies: Contact centre agents prefer to be appointed to permanent positions rather than employed as a temporary staff. A temporary appointment does not provide job security thereby exacerbating turnover.

The work itself: This refers to the extent to which the job provides the individual with stimulating tasks, captures his/her interest, presents opportunities for learning and provides for autonomy, personal growth, the opportunity to be responsible and to be accountable for results, as well as regular feedback on performance. The individual must experience his/her work as being worthwhile and important.

Relationships: The staff of the entire organisation should work together to help one another. All the employees, as well as the supervisors, should form a co-ordinated unit that will cultivate good relations with customers.

Managerial support: This is the degree to which contact centre employee believe that organisation provides them with the needed support (practically and emotionally) and cares about their well-being.

Organisational commitment: Successful organisations show respect for each employee's qualities and contribution, regardless of his/her job level.

Work-life balance and physical environment: This refers to the ergonomic factors that exist between people, their work activities, their equipment, the work system and the environment to ensure that workplaces are safe, comfortable and efficient to promote work with minimal strain or fatigue.

Leadership capability: This is management's ability to demonstrate interest in and concern for employees. It implies that respect, trust and fairness in relationships with supervisors need to be executed and supported.

CONCLUSION

Managing employee retention in the contact centre industry is challenging because turnover in the industry is always likely to be higher than that in other fields of employment. While it is necessary to accept this fact, it is nevertheless important not to give up trying to retain employees. In any industry, one of the most effective tools is empowerment. If employees feel empowered in their jobs and truly valued by the company they work for, they are far more likely to stay. A contact centre position may not always be the most exciting job, but employers should always remember that it is not just the role that makes an employee feel valued. The actions of the employer and the prevailing workplace culture are equally important.

The intention to leave in the contact centre industry is largely influenced by job dissatisfaction, lack of commitment to the organisation and feelings of stress. However, managers who are concerned about the impact of the intention to leave on possible turnover should realise that they have some control over these variables. In particular, job stressors that trigger process leading to the intention to leave can often be adjusted. Supervisor support is an influential aspect that can reduce the impact of stressors and the intention to leave. Monitoring workloads and supervisor-subordinate relationships may not only reduce stress, but increase job satisfaction and commitment to the organisation. Furthermore, given their role in leaving intentions, managers need to monitor both intrinsic and extrinsic sources of job satisfaction available to employees. This action may in turn reduce the number of employees who intend to leave with subsequently turnover, thereby saving organisations considerable financial costs and effort involved in the recruitment, induction and training of replacement staff.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABBASI S.M. & HOLLMAN K.W. 2000. Turnover: the real bottom line. Public Personnel Management, 29(3):333. [ Links ]

AMIG S. & JARDINE E. 2001. Managing human capital behaviour. Health Management, 21(2):22-26. [ Links ]

AUTRY C. & DAUGHERTY, P. 2003. Warehouse operation employees: linking person organization fit, job satisfaction and coping responses. Journal of Business Logistics, 24(1):171-197. [ Links ]

BATT R. 2002. Managing customer service, human resource practices, quit rates and sales growth. Academy of Management Journal, 445(3):587-597. [ Links ]

BELT V., RICHARDSON R. & WEBSTER J. 2002. Women, social skills and interactive service work in telephone call centres. New Technology, Work and Employment, 17(1):20-34. [ Links ]

BENNER C. 2006. South Africa on call: information technology and labour market restructuring in South Africa call centres. Human Resource Management Journal, 40 (9):1025-1040. [ Links ]

BEVERLY L. & PHILLIP L. 2006. Employee engagement: conceptual issues. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communication and Conflict, 5(2):103. [ Links ]

BORSTORFF P.C. & MARKER M.B. 2007. Turnover drivers and retention factors affecting hourly workers: what is important? Management Review: an International Journal, 2(1):14-27. [ Links ]

BURLEIGH S., EISENBERG B., KILDUFF C. & WILSON K.C. 2001. The role of the value proposition and employment, branding in retaining top talent society for human resource management. [Online]. Available from http://www.my.shrm.org [Accessed: 07/12/2008]. [ Links ]

BURGESS S. 1998. Analyzing firms, jobs and turnover. Monthly Labour Review, 121(7):55-58. [ Links ]

BLESS C. & HIGSON-SMITH C. 2000. Fundamentals of social research methods: An African perspective. 3rd ed. Cape Town: Zebra Publications. [ Links ]

BLUM T.C., GILSON L.L. & SHALLEY C.E. 2000. Matching creativity requirements and the work environment: effects on satisfaction and intentions to leave. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2):215-224. [ Links ]

CALL CENTRE ASSOCIATION (CCA) RESEARCH INSTITUTION. 2001. The state of the centres: an investigation of the skills level in the industry, and of training requirements. Report for the Department for Education and Skills. Glasgow. [ Links ]

CALL CENTRE NEWS SERVICE. 1999. What affects design? [Online]. Available from http://www.callcenternews.com [Accessed: 15/02/2009]. [ Links ]

COLARELLI S.M. 1984. Method of communication and mediating processes in realistic job previews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69:633-642. [ Links ]

COLQUITT J. 2001. On the dimensionality of organisational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86:386-400 [ Links ]

DE VOS A.S. 1998. Research at grass roots: A primer for the caring professions. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

DIXON-KHEIR C. 2005. Supervisors are key to keeping young talent. Human Resource Magazine, 45(1):139. [ Links ]

DOBBS K. 2001. Knowing how to keep your best and brightest workforce. Human Resource Management Journal, 80(4):57. [ Links ]

EISENBERGER R., STINGLHAMBER F., VANDERBERGHE C., SUCHARSKI I. & ROADES, L. 2002. Perceived supervisor support: contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3):565-573. [ Links ]

FRANK F.D. 2004. Introduction to the special issue on employee retention and engagement. Journal of Human Resource Planning, 12(1):27. [ Links ]

GALLAGHER J. 2004. Reducing call centre turnover. Insurance and Technology, 23(3):43. [ Links ]

GALLOP D. 1997. Employee engagement, business success. [Online]. Available from: http://www.bcpublicservica.ca [Accessed 05/03/2008]. [ Links ]

GALUNIC C. & ANDERSON E. 2000. From security to mobility: generalized investment in human capital and agent commitment, organization science. Journal of Institute of Management Science, 11(1):1-2. [ Links ]

GARAVAN T.N., WILSON J.P., CROSS C. & CARBERY R. 2008. Mapping the context and practice of training, development and HRD in European call centres. Journal of European Industrial Training, 32(8):612-628. [ Links ]

GUTHRIE P.J. 2001. High involvement work practices, turnover and productivity: evidence from New Zealand. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1):180-191. [ Links ]

HACKMAN J.R. & OLDHAM G.R. 1980. Work redesign. Lebanon, MA: Addidon-Wesley. [ Links ]

HARTER J.K., SCHMIDT F.L. & HAYES T.L. 2002. Business-unit level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87:268-279. [ Links ]

HOULIHAN M. 2004. Tension and variation in call centre management strategies: a cross-national report. Basingstoke: Palrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

JURKIEWICZ C.L. 2000. Generation X and the public employee. Public Personnel Management, 29(1):55. [ Links ]

KLEEMANN F. & MATUSCHEK I. 2002. Between job and satisfaction: motivations and career orientations of German "high quality" call centre employees. [Online]. Available from http://www.sociology.org [Accessed: 05/03/2009]. [ Links ]

LEE J. 2008. Finding and keeping call centre agents in today's competitive market. [Online]. Available from http://www.callcentretime.com [Accessed 25/11/2008]. [ Links ]

LEEDY P.D. & ORMROD J.E. 2005. Practical research: planning and design. 8th ed. New Jersey: Kevin. [ Links ]

LONGENECKER C. & SCAZZERO J. 2003. The turnover and retention of IT managers in rapidly changing organizations. Information Systems Management, 9(2):59-65. [ Links ]

LORD R. 2002. Traditional motivation theories and older engineering. Engineering Management Journal, 14(3): 3-7. [ Links ]

MAINIERO L.A. 1993. Is your corporate culture costing you? Academy of Management Executive, 7(4):84-86. [ Links ]

MICHLITSCH J. 2000. High-performing, loyal employees: the real way to implement strategy. Strategy and Leadership, 28(6):28. [ Links ]

MITCHELL T.R., HOLTON B.C. & LEE T.W. 2001. How to keep your best employees: developing an effective retention policy. Academy of Management Executive, 15(4):96-99. [ Links ]

MOBLEY W.H., GRIFFETH R.W., HAND H.H. & MEGLINO B.M. 1979. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin, 86:493-522. [ Links ]

OH T. 2001. Managing your turnover drivers. Human Resource Focus, 78(3):12-14. [ Links ]

PATTON M.Q. 2002. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

RHOADES L., EISENBERGER R. & ARMELI S. 2001. Affective commitment to the organisation: The contribution of perceived organisational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5):825-836. [ Links ]

ROSSOUW D. 2003. Intellectual tools: skills for the human science. 2nd ed. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

SAKS A.M. 2006. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7):600-619. [ Links ]

SCHAUFELI W.B. & SALANOVA M. 2007. Work engagement: an emerging psychological concept and its implications for organizations. In: S.W. Gilland, D.D. Steiner & D.P. Skarlicki (eds.). Research in social issues in management: managing social and ethical issues in organizations. Volume 5. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishers: 41. [ Links ]

SHERINDAN J.E. 1992. Organizational culture and employee retention. Academy of Management Journal, 35(5):1036-1056. [ Links ]

TAYLOR G. 2002. Focus on talent. Training and Development, 56(12):26-38. [ Links ]

TEPPER B.J. 2000. Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2):178-201. [ Links ]

THORNTON S. 2001. How communication can aid retention. Strategic Communication Management, 5(6):24-30. [ Links ]

ULRICH D. 1998. Intellectual capital, competence X commitment. Sloan Management Review, 39(2):11-18. [ Links ]

VAZIRANI N. 2007. Employee engagement. Berkerley: SIES College of Management Studies. [ Links ]

WELLINS R.S., BERNTHAL P. & PHELPS M. 2007. Employee engagement: The key to realising competitive and advantage. Bridgeville: DDI. [ Links ]

WITHERS P. 2001. Retention strategies that respond to worker value. Workforce, 80(7):36-41. [ Links ]