Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The total customer experience as a sustainable strategic differentiator

A DrotskieI; FJ HerbstII

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Johannesburg

IIUniversity of Stellenbosch Business School

ABSTRACT

The total customer experience is a sustainable and relevant strategic differentiator in all industries today that interact with customers. The sustainability and relevance lie in the fact that the customer experience evolved over time and encompasses previous potential differentiators.

Through literature review, this article provides an overview of the evolution of the total customer experience and depicts the fact that a total customer experience encompasses other differentiators that industries identified as potential differentiators over time, leading to sustainability.

Key phrases: Differentiation, sustainability, total customer experience, strategic differentiator, competitive advantage

INTRODUCTION

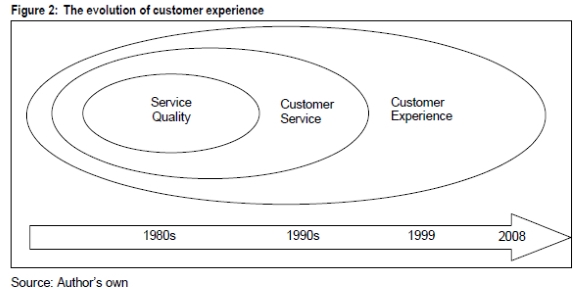

The evolution of the customer experience is a phenomenon that is found in literature and practice since the 1980s. Strategic differentiation was found in service quality during the 1980s, evolving into customer service in the 1990s and currently the total customer experience is seen as a strategic differentiator in industries who interact with customers.

Organisations are trying to find sustainable strategic differentiators leading to a competitive advantage in their industry. The research depicted in this article implies that the total customer experience can be the sustainable strategic differentiator. The researcher focused the research on the retail banking industry as an example of an industry interacting with customers.

The primary objective of the research is to investigate whether customer experience is a strategic differentiator in retail banking, leading to a sustainable competitive advantage.

This article will provide an overview of customer experience as a potential strategic differentiator by defining the concept customer experience and its elements and the evolution of customer experience over time through a literature review.

DEFINING CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE AS CONCEPT AND ITS ELEMENTS

This article is focused on the total customer experience as differentiator. It is therefore important to first define the concept of customer experience and its elements.

Customer experience is defined by various authors in various ways. Their words differ, but a key message, namely that it starts with the customers and their emotions and behaviours when interacting with an organisation, runs through all the definitions like a golden thread. It is also clear from the definitions that customer experience incorporates service quality and customer service.

It is clear from the definitions that total customer experience is a concept that evolved over time to become a systemic and holistic concept focused on the customer. It is about a "human" interaction and therefore the emotions of customers are a vital part of an experience.

The author believes that the definition by Seybold (2002:108) namely "a total customer experience is a consistent representation and flawless execution, across distribution channels and interaction points, of the emotional connection and relationship you want your customers to have with your brand" encompasses all the most important aspects of the total customer experience.

The customer experience is felt in all interactions with an organisation and therefore it is important to understand that customers interact with an organisation through various means and the experience must always be the same. This is true for any services organisation including retail banking. With the evolution of retail banking the means through which customers interact with banks are continuously expanding, making the challenge even more relevant.

Elements of total customer experience

From the definitions of total customer experience given above it is clear that a total customer experience consists of a variety of elements.

The following key elements of customer experience are entrenched across the organisation (Shaw 2005:xix), namely strategy, culture, customer expectations, processes, channel approach, marketing and brand, systems, people and measurement.

According to Shaw (2005:xix), each of these elements represents an area in the organisation that has an extensive effect on customer experience.

Strategy

The first important element of a total customer experience is strategy. Organisations require a strategy that creates a unified view of customers from the perspectives of operations, analytics and collaboration along the entire customer relationship value chain (Heskett, Sesser & Schlesinger 1997:106).

Culture

The second important element of a total customer experience is culture. Culture refers to the shared values, vision or credo that creates a propensity for individuals to act in certain ways. According to Hrebiniak (2005:261) organisational culture includes the norms and values of the organisation, including the vision shared by its personnel. Culture usually has a behavioural component, defining the "way an organisation does things".

According to Basch (2002:2-3), human behaviour is based on culture. If the organisational culture is dedicated to providing a high level of service to customers, its employees will provide that service. The six main qualities of a well-designed cultural system devoted to customer care are:

(i) Vision (a clear picture of the customer experience you want to provide).

(ii) Values (an inviolable code or rules of behaviour).

(iii) Goals (specific results the organisation wants to achieve during a specific period).

(iv) Relevance (the desire people feel about achieving a goal because they find it meaningful).

(v) Actions (the particular steps people take to achieve goals).

(vi) Feedback (the measurement system that assesses organisational achievements).

Customer expectations

The third important element of a total customer experience is customer expectations. The expectations of customers serve as a benchmark in terms of which present and future service encounters can be compared. Customer expectations are what customers think they will receive from a service encounter. These expectations may be divided into at least three levels.

(i) The predicted service level (the anticipated level of performance).

(ii) The desired service level (the level of service the customer wants or hopes to receive compared to the predicted service level).

(iii) The adequate service level (the minimum level of service the customer will tolerate or accept without being dissatisfied) (Cant, Brink & Brijball 2002:239).

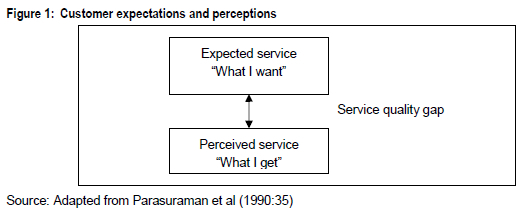

Parasuraman, Berry and Zeithaml (1990:34) state that customers evaluate an organisation's service quality by comparing service performance (perceptions) with what they think performance should be (expectations). Customers' service expectations provide a context for their assessment of the service. When service performance falls short of expectations a service quality gap results as depicted in Figure 4.4 below.

A number of different attributes contribute to understanding customer expectations and customer loyalty, namely people, product and service delivery, place (convenience), product features, price, policies and procedures, and promotion and advertising (Smith 2001:5). Two primary components exist in this context, namely physical and relational. Physical context is referred to as "mechanics clues" (sights, smells, sounds and textures). Relational context is referred to as "humanic clues" (people behaviours). Managing customer experience means "orchestrating" all these "clues" to meet or exceed people's emotional needs and expectations. A successful service experience provider such as Disney spends many months on training employees in relational methods for them to connect emotionally with guests during social interactions (Pullman & Gross 2003:218).

Processes

The fourth important element of a total customer experience is process. According to the Oxford dictionary, a process is "a series of actions or tasks performed in order to do, make or achieve something" (Hornby 1998:922).

Once organisations have a shared view of customer experience, processes are needed to reinforce and support the goal of improving customer experience (Dorsey & Bodine 2006:7).

Channel approach

The fifth important element of a total customer experience is the channel approach (delivery). Self-service will be part of transforming customer experience. However, to be successful, the customer self-service initiative should integrate the right technology, business processes and user adoption strategies.

According to Lee (2002:242), it is acknowledged that retail banks and their customers expect benefits in two different channels of the marketing of financial products and services: face-to-face and directly. Banks have to provide financial products and services via different delivery channels to meet the different needs of customers. Finding the right delivery channel will facilitate the marketing of their products and services and promote long-term relationships. The key is to deliver the right mix of products and services via the right channels to the right segments of customers.

Marketing and brand

The sixth important element of a total customer experience is marketing and the brand.

Marketing is defined as "a social process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products and value with others" (Kotler 1984:4). More recently, Hair, Bush and Ortinau (2006:5) state that marketing's purpose is to enable an organisation to plan and implement "pricing, promotion and distribution or products, services and ideas" to create satisfaction, as described in paragraph 1.5.

According to Aaker and Keller (1990:29) an important brand association is the overall brand attitude. Brand attitude is based on certain attributes such as durability, incidence of defects, serviceability, features and performance. Attitude is conceptualised in terms of the customer's perception of the overall quality of the brand.

An organisation's first step in managing total customer experience is recognising the clues it is sending to customers. The clues that make up a customer experience are everywhere and easily discerned. Anything that can be perceived or sensed - or recognised by its absence - is an experience clue. Thus the product or service provides one set of clues, the physical setting offers more clues, and the employees - through their gestures, comments, dress and tone of voice - provide still more clues (Berry, Carbone & Haeckel 2002:85-86).

"A strong brand promise can influence what customers remember about their experiences with a product or service" (Barlow & Steward 2004:42). Barlow and Steward (2004:45) also believe that a brand idea can be enforced by means of pictures, language and behaviour - all of which evoke emotions. Human behaviour is the primary means of brand reinforcement within the realm of customer service.

"Branding should be the differentiating mechanism, separating an organisation's products and services from those of its competitors" (Kumar 2004:148). It is the brand that shapes customer experience. Customers come to a brand with a set of assumptions about that brand. The brand and the customer experience should correspond (Shaw 2005:137).

Systems

The seventh element of a total customer experience is systems. Systems are designed and managed in organisations through information technology (IT). IT enables modern organisations to integrate their supply, production and delivery processes so that operations are triggered by customer orders, not by production plans that push products and services through the value chain. An integrated system, from customer orders upstream to raw material suppliers, enables all the organisational units along the value chain to realise enormous improvements in cost, quality and response time (Kaplan & Norton 1996:4).

Aligning business processes with IT functions will remain an elusive goal without real insight into customer experience. The quality of the customer experience must become the ultimate baseline and hence the natural departure point for an effective service-level agreement. In other words, managing infrastructure must begin by capturing and benchmarking user experience as realistically as possible. Only when customer experience is understood realistically will the organisation obtain the data it needs to map its technology investments in terms of its business objectives. This is the ultimate scorecard for prioritising everything from real-time troubleshooting to infrastructure optimisation and service planning (Drogseth 2005:64).

People

People are the eighth important element of a total customer experience. People, also referred to as personnel or employees, represent the "key battleground for many organisations" (Ind 2001:67-72). An organisation in Stockholm (Ind 2001:67-72) defined 4Fs to steer its employees: fun, fame, fortune and future. The 4Fs were designed to influence how people behaved internally and how they interacted with customers.

Service organisations cannot compete effectively without effective service - which is performed by people. In creating value for customers, service organisations have to invest in attracting, developing, motivating and retaining quality personnel. To excel in external marketing, service organisations first have to excel at internal marketing before they can excel in external marketing (Berry & Parasuraman 2000:1).

Finnie (1994:25-26) says that "loyalty is the acid test of leadership. It is the best way to know whether a leader is achieving financial results through the success of employees and customers or at their expense. It is through their employees that leaders are going to change the customers' experience".

THE EVOLUTION OF CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE

The concept of a total customer experience as utilised in this article evolved over time. Figure 2 shows this evolution from a service quality focus during the 1980s to a customer service focus during the 1990s and recently a total customer experience focus. This shift in focus is found in strategies of organisations where "quality" was a well-known concept in vision statements during the 1980s, moving to "customer focus" or "customer centric" being utilised in vision statements during the 1990s. It is important to note in Figure 2 that customer experience includes the concepts of customer service and service quality.

The modern concept of customer service has its roots in the craftsman economy of the 1800s, when individuals and small groups of manufacturers competed to produce arts and crafts to meet public demand. The advent of mass production in the early twentieth century, followed by an explosion in the demand for goods after World War II, increased the power of suppliers at the expense of consumers and reduced the importance of customer service. A shift in this balance began in the 1970s, as international competition increased and the dominance of Western manufacturing was challenged, first by Japan, then by Korea, China and other developing economies. Producers responded by improving the quality of their products and services (Berry 1999 in Zeithaml & Bitner 2003:11-12).

According to Zeithaml and Bitner (2003:11-12), many organisations jumped on the service bandwagon during the 1980s and early 1990s, investing in service initiatives and promoting service quality to differentiate themselves and create a sustainable competitive advantage. Many of these investments were based on faith and intuition by managers who believed in serving customers well and who believed that quality service made good business sense. Since the mid-1990s, organisations began to demand hard evidence of the bottom-line effectiveness of their service strategies.

According to Blanchard and Galloway (1994:5-7), the economic boom of the 1990s increased the power of suppliers who, whilst not completely reverting to lower standards of service, were able to be more selective about the customers they wanted to serve and what level of service they were prepared to provide.

The financial services sector has seen a growing intensity of competition within the market place, particularly over the past two decades. The competition emerged in the 1970s when banks and building societies based their major competitive strategies on the traditional marketing mix elements of product, price, promotion and place. This led, in the eyes of the customer, to homogeneity rather than distinction and a competitive strategy based on full product lines (Blanchard & Galloway 1994:5-7).

A good example of the evolution of customer experience is the mobile phone market in Europe. According to Shaw (2005:5), this industry enjoyed massive growth during the late 1990s and early 2000s and effectively could not care less about customer experience.

The 1980s: service quality focus

Galloway & Blanchard (1996:22-29) says that during the 1980s customer awareness led to a greater degree of customer sovereignty and organisations could no longer afford to neglect customer needs. The differentiator that provided a competitive advantage at the time was quality of service.

During the 1980s, the focus was mainly on customer satisfaction. An entire debate stemmed from the differences in service quality and customer satisfaction and the causal relationship between them. Satisfaction studies attempted to measure expectations at the same time as perceptions. Customer satisfaction was defined as "a transitory judgement made on the basis of a specific service encounter whereas service quality is a global assessment based on long-term attitude" (Mattila 2005:97).

According to Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry (1985:41), attaining quality in products and services became a pivotal concern during the 1980s. But although marketers described and measured the quality of tangible goods, the quality of services remained largely undefined and unresearched.

As services are considered intangible, organisations may find it more difficult to understand how customers perceive their services and service quality. "Service quality is a measure of how well the service level delivered matches customer expectations. Delivering quality service means conforming to customer expectations on a consistent basis" (Parasuraman et al 1985:42).

According to Vargo and Lusch (2004:2, 5) marketing has moved from a goods-dominant view in which tangible output and discrete transactions were central to a service-dominant view towards the 21st Century. In a service-dominant view intangibility, exchange processes and relationships are central. "The service-centered dominant logic represents a reoriented philosophy that is applicable to all marketing offerings, including those that involve tangible output (goods) in the process of service provision" (Vargo & Lusch 2004:2). The service-centered view of marketing implies a series of social and economic processes focused on competitive value propositions.

Parasuraman et al (1985:35) also said that competing organisations in the 1980s provided the same types of service, but they did not provide the same quality of service. Thus service quality became the great differentiator, the most powerful weapon of service organisations.

Parasuraman et al (1985:45-46) determined ten determinants of service quality by using focus groups: reliability, responsiveness, competence, access, courtesy, communication, credibility, security, understanding the customer and tangibles.

During the 1980s and 1990s, authors like Lehtinen (1996), Berry (1985), Parasuraman (1985), Zeithaml (1985) and Grönroos (1996) agreed that service consisted of an outcome and a process element. Galloway & Blanchard (1996:22-29) also provided a classification of service quality.

Lehtinen and Lehtinen (in Galloway & Blanchard 1996:22-29) identified three dimensions of service quality.

(i) Physical quality (equipment, premises and tangibles).

(ii) Corporate quality (image and profile of the organisation).

(iii) Interactive quality (customer contact with service personnel).

Grönroos (in Galloway & Blanchard 1996:22-29) identified five key determinants of service quality.

(i) Professionalism and skills.

(ii) Reputation and credibility.

(iii) Behaviour and attitudes.

(iv) Accessibility and flexibility.

(v) Reliability and trustworthiness.

Zeithaml and Bitner (2003:3) define service as deeds, processes or performance. Carlzon (Curry & Penman 2004:331-333) states that quality in the service operation is created at the "moment of truth". However, technology in the provision of services tends to make the "moment of truth" a mechanical experience, lacking in emotion.

During the late 1980s providers of professional services awakened to consumer challenges and the realities of marketing. With these changes, a related and equally important issue emerged - service quality and evaluating the service encounter. Evaluation of a service encounter has one of two outcomes: satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Zeithaml and Bitner (2003:86) define satisfaction as "the customer's fulfilment response. It is a judgement that a product or service feature, or the product or service itself, provides a pleasureable level of consumption-related fulfilment". Zeithaml and Bitner (2003:86) then also state that a failure to meet the needs and expectations of a customer results in dissatisfaction.

Organisations which provided a superior service achieved better business results (Keiser 1988:65-66). In a 15-year study, the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Strategic Planning Institute compared organisational growth and profitability. The study indicated that market share, return on investment and asset turnover are all linked to the perceived quality of an organisation's goods and services. Regardless of the industry, service quality is one of the most powerful tools for shaping perceptions of overall quality. However, it is difficult to attain superior quality in the services sector, and correcting a customer service problem requires tremendous effort over a long period of time.

In today's marketplace, service has to be outstanding. If it is not outstanding, it will be considered mediocre. The principal objective of an organisation that focuses on service quality should be the integration of a service quality philosophy into customer-service training (Spechler 1989:20-21).

At the end of the eighties new rules of thumb emerged in the service industry (Liswood 1989:42-45).

(a) It costs five times as much to get a customer than to keep one.

(b) It takes twelve positive service experiences to overcome one negative experience.

(c) 25 to 50 percent of the operating expenses of an organisation can be attributed to poor service quality - to the cost of not doing it right the first time.

Liswood (1989:42-45) says that organisations who lose customers are spending more than they need to; they are wasting valuable assets. This raises two questions: Shouldn't stock analysts, investment brokers, venture capitalists, bankers and others have a clear way to confidently evaluate their services? Shouldn't those results get factored into any sales price or investment decision?

Customer service quality was a widespread concern in the banking industry in the late1980s. If they were to manage service quality effectively, banks had to define what service quality meant to their customers before they could develop ways to measure quality and control it. Probably the most critical weakness in service quality programmes was the lack of effective, ongoing measurement. However, measurement alone would not maximise an institution's customer service performance. Employees who met or exceeded service goals should have been formally recognised and rewarded (Brewton 1989:92).

During the 1980s the emphasis of both academic and managerial effort focused on determining what service quality meant to customers and developing strategies to meet customer expectations. Since then, many organisations have instituted measurement and management approaches to improve their service. The service quality agenda has shifted and been reconfigured to include other issues, for example understanding the impact of service quality on profit and other financial outcomes of organisations (Zeithaml, Berry & Parasuraman 1996:31).

Howcroft (Blanchard 1991:5) defined service quality as follows: "... service quality in banking implies consistently anticipating and satisfying the needs and expectations of customers".

The most widely reported framework for service quality in the 1980s is the one proposed by Parasuraman et al (1985:41-50), consisting of five dimensions.

(i) Tangibles: physical facilities, equipment and appearance of personnel.

(ii) Reliability: the ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately.

(iii) Responsiveness: willingness to help customers and to provide prompt service.

(iv) Assurance: the knowledge and courtesy of employees and their ability to inspire trust and confidence.

(v) Empathy: caring, individualised attention to customers.

The expectations component of this service quality framework (SERVQUAL) is a general measure and pertains to the service levels customers believe excellent organisations in an industry should deliver (Parasuraman, Berry & Zeithaml 1993:141).

The 1990s: customer service focus

During the 1990s the focus shifted from an internal quality focus to a more external customer focus. Organisations started realising that satisfied customers as measured in terms of quality is not enough to create differentiation in an industry.

Zeithaml and Bitner (2003:4) define customer service as "the service provided in support of a company's core products".

According to Coskun and Frohlich (1992:15-16), the quality of an organisation's products and services was one of the most important factors in creating a competitive edge. Customer service plays a pivotal role in developing quality, particularly if the organisation's product is service. In banking, the competitive edge almost exclusively derives from the quality of the bank's services.

Coskun and Frohlich (1992:15-16) also says that in the past, service was often mistakenly equated with courtesy. Because of this misconception, banks invested heavily in technology in the belief that it would improve their services. As financial institutions tried to improve their efficiency by introducing technology, their products (the supply side) became more standardised (ie dehumanised) and the quality of their customised services declined. On the demand side, however, the pressure increased for banking to be more humanised (customised).

Banking is one of the most personal and sensitive issues from a customer's perspective. As social conditions make it more difficult for customers to survive financially, a customer's relationship with a particular bank becomes more crucial. For this reason the quality of the bank/customer relationship has been regaining attention. Surveys indicate that truly meeting customer needs is the key to customer retention (Coskun & Frohlich1992:15-16).

1999 and the 2000s: Total customer experience focus

The researcher derived from the information thus far that organisations began to realise that a satisfied customer cannot only be measured in terms of the tangible qualities of products and services. Emotional attitudes and behaviours started to play a role in customer experiences, leading to a holistic approach to customer experience (encompassing product, price and service delivery).

Organisations subsequently evolved to where they currently are with respect to customer experience. The challenge is to understand customer experience as a concept.

CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE AS STRATEGIC DIFFERENTIATOR - THE IMPLICATIONS

This article focuses on customer experience as strategic differentiator. It is therefore important to define differentiation.

The following definitions of differentiation were derived from literature:

(i) Goldman and Nieuwenhuizen (2006:77): "Differentiation is seen as strategy in which an organisation seeks to distinguish itself from its competitors through the quality of its products and services".

(ii) Pearce and Robinson (2007:237): "A business strategy that seeks to build competitive advantage with its product or service by having it be "different" from other available competitive products based on features, performance or other factors not directly related to cost and price. The difference would be one that would be hard to create and/or difficult to copy or imitate".

(iii) Porter (1980:37-38): "Differentiation is a viable strategy for earning above-average returns in an industry because it creates a defensible position for coping with the five competitive forces (threat of new entrants, bargaining power of buyers, threat of substitute products and services, bargaining power of suppliers and rivalry amongst existing competitors)...Differentiation provides insulation against competitive rivalry of brand loyalty by customers and resulting lower sensitivity to price".

According to the Oxford dictionary (Hornby 1998:322), to differentiate is "to see or show that two things are different; to be a mark of difference between people or things".

Differentiation in the context of this article is defined as "strategic" differentiation and is therefore of strategic importance. A differentiation strategy is therefore needed to ensure sustainable competitive advantage.

This article focused thus far on the definition and evolution of customer experience and also explained what strategic differentiation entails.

Figure 2 depicted the evolution of customer experience over time and shows that customer experience includes service quality and customer service. Therefore the total customer experience incorporates service quality and customer service which were both potential strategic differentiators during the 1980s and 1990s. The article also includes the elements of a total customer experience. The comprehensive scope of the total customer experience makes it a potential strategic differentiator.

It is therefore clear from all the evidence above that the total customer experience is an encompassing concept consisting of various elements that includes the products, services, processes, systems, strategy and employees involved in an interaction between the customer and the organisation. It also includes previous possible differentiators identified in customer-centric industries.

If organisations can formulate a customer experience strategy which addresses the objectives to be achieved regarding all the elements of a total customer experience and implements the strategy successfully, it can lead to a differentiated position in an industry - strategic differentiation.

This differentiation must be sustainable in order for it to lead to a competitive advantage. The fact that the total customer experience is such a holistic concept encompassing elements that depict the total process of interaction with a customer and it includes the previous possible differentiators in a customer-centric context, lead to sustainability in differentiation.

CONCLUSION

This article provided evidence from literature on the definition and elements of a total customer experience and the evolution towards the concept customer experience. Within the retail banking industry, an example of an industry which interacts with customers, it is clear from literature that service quality and customer service have been potential strategic differentiators over time.

As customer experience evolved over time it has the potential of being a sustainable strategic differentiator due to its holistic and encompassing nature and its elements.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AAKER D.A. & KELLER K.L. 1990. Consumer evaluations and brand extensions. Journal of Marketing, January, 54:27-41. [ Links ]

BARLOW J. & STEWART P. 2004. Branded customer service - the new competitive edge. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. [ Links ]

BASCH M.D. 2002. Customer culture. New York: Financial Times, Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

BERRY L.L., CARBONE L.P. & HAECKEL S.H. 2002. Managing the total customer experience. MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring:85-89. [ Links ]

BERRY L.L. & PARASURAMAN A. 2000. Internal Marketing: Directions for Management. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

BLANCHARD R.F. & GALLOWAY R.L. 1994. Quality of retail banking. International Journal of Services Industry Management, 5(4):5-23. [ Links ]

BREWTON J.P. 1989. Better commitment breeds better service. ABA Banking Journal, October:92. [ Links ]

CANT M.C., BRINK A. & BRIJBALL S. 2002. Customer behaviour - a Southern African perspective. Cape Town: Juta (Pty) Ltd. [ Links ]

COSKUN A. & FROHLICH C.J. 1992. Service: the competitive edge in banking. Journal of Services Marketing, 6(1):15-22. [ Links ]

CURRY A. & PENMAN S. 2004. The relative importance of technology in enhancing customer relationships in banking. Managing Service Quality, 14(4):331-341. [ Links ]

DORSEY M. & BODINE K. 2006. Culture and process drive better customer experiences. Forrester Research, 1-12. [ Links ]

DROGSETH D. 2005. Business alignment starts with quality of experience. Business Communication Review, March:60-64. [ Links ]

FINNIE W.C. 1994. Hands-on strategy, the guide to crafting your company's future. Canada: Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

GALLOWAY R.L. & BLANCHARD R.F. 1996. Variation in the perception of quality with lifestage in retail banking. international Journal of Bank Marketing, 14(1):22-29. [ Links ]

GOLDMAN G. & NIEUWENHUIZEN C. 2006. Strategy: sustaining competitive advantage in a global context. Cape Town: Juta (Pty) Ltd. [ Links ]

HAIR J., BUSH R. & ORTINAU D. 2006. Marketing research within a changing environment. 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

HESKETT J.L., SESSER JR W.E. & SCHLESINGER L.A. 1997. The service profit chain. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

HORNBY A.S. 1998. Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

HREBINIAK L.G. 2005. Making strategy work, leading effective execution and change., New Jersey: Wharton School Publishing. [ Links ]

IND N. 2001. Living the brand: how to transform every member of your organisation into a brand champion. London: Creative Print and Design. [ Links ]

KAPLAN R.S. & NORTON D.P. 1996. The balanced scorecard. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

KEISER T.C. 1988. Strategies for enhancing service quality. The Journal of Services Marketing, 2(3):65-70. [ Links ]

KOTLER P. 1984. Marketing management: analysis, planning and control. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

KUMAR N. 2004. Marketing as strategy: understanding the CEO's agenda for driving growth and innovation. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing. [ Links ]

LEE J. 2002. A key to marketing financial services: the right mix of product, services, channels and customers. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(3):238-258. [ Links ]

LISWOOD L.A. 1989. A new system for rating service quality. The Journal of Business Strategy. July/August: 42-47. [ Links ]

MATTILA A. 2005. Relationship between seamless use of experience, customer satisfaction and recommendation. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 1:96-108. [ Links ]

PARASURAMAN A., BERRY L.L. & ZEITHAML V.A. 1993. More on improving service quality measurement. Journal of Retailing, 69(1):140-147. [ Links ]

PARASURAMAN A., ZEITHAML A. & BERRY L.L. 1985. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49:41-50. [ Links ]

PARASURAMAN A., BERRY L.L. & ZEITHAML A. 1990. Guidelines for conducting service quality research. Marketing Research, December:34-40. [ Links ]

PEARCE II J.A. & ROBINSON JR R.B. 2007. Strategic Management. Formulation, implementation and Control. 10th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin. [ Links ]

PORTER M.E. 1980. Competitive Strategy. Techniques for analysing industries and competitors. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

PULLMAN M.E. & GROSS M.A. 2003. Welcome to your experience: where you can check out anytime you'd like, but you can never leave. Journal of Business and Management, 9(3):215-232. [ Links ]

SEYBOLD P.B. 2002. The customer revolution. London: Business Books. [ Links ]

SHAW C. 2005. Revolutionalise your customer experience. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

SMITH S. 2001. Profiting from the customer experience economy. The Forum Corporation, April:1-6. [ Links ]

SPECHLER J. 1989. Training for service quality. Training and Development Journal, May:20-26. [ Links ]

VARGO S.L. & LUSCH R.F. 2004. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, January, 68:1-17. [ Links ]

ZEITHAML A., BERRY L.L. & PARASURAMAN A. 1996. The behavioural consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60:31-46. [ Links ]

ZEITHAML V.A. & BITNER J.B. 2003. Services marketing: integrating customer focus across the firm. 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]