Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of Contemporary Management

versión On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Evaluating SMEs corporate social performance: a stakeholder perspective

EE Smith; S Perks

Department of Business Management, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University

ABSTRACT

This article sets out to investigate the extent to which SMEs in the Nelson Mandela Metropole evaluate corporate social performance and taking care of stakeholder concerns. To achieve the research objectives, a comprehensive literature study was conducted as to provide a theoretical framework for the empirical study. Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to a non-probability convenient sample of 228 SMEs in the designated region. To investigate the relationships between the independent and dependent variables, twelve null-hypotheses were tested. Perceptions regarding evaluating social performance, stakeholder concerns and classification data variables were tested. The results revealed highly significant relationships between these variables. SMEs should disclose their social and environmental performance alongside their financial performance. By accepting and practising social performance obligations and sustainable development principles, SMEs would be more responsive towards the concerns and needs of owners/investors, customers, employees and the community. Practical guidelines are provided for evaluating social performance from a stakeholder perspective.

Key phrases: Social responsibility, corporate social performance, stakeholder concerns, social obligations, sustainable development, small and medium enterprises

"... the survival and continuing profitability of the corporation depend upon its ability to fulfill its economic and social purpose, which is to create and distribute wealth or value sufficient to ensure that each primary stakeholder group continues as a part of the corporation's stakeholder system.

(Moneva, Rivera-Lirio & Muñoz-Torres 2007:84)

INTRODUCTION

Murillo and Lozano (2006:227) argue that the academic literature reveals the need for undertaking more studies as to discover the perceptions surrounding corporate social performance (CSP) in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and that they still have a long way to go in terms of informing stakeholders of their best practices regarding CSP. Perrini (2006:305) contends that many of the literature dealing with CSP are more relevant to larger organisations and that there is a need for establishing the relationship between CSP and SMEs. Sang (2008:337) is also of the opinion that most SMEs lack social responsibility consciousness. With heightened public interest in corporate social responsibility, many organisations are discovering that they can't avoid having people evaluate how well they perform in this respect (Hellriegel, Jackson, Slocum, Staude & Associates 2004:138). Theron (2005:2) simply define corporate social responsibility (CSR) as distinguishing right from wrong and being a good corporate citizen. Engageweb.org (2008) elaborates on this definition and views it as recognising and addressing the needs of all groups which are affected by the activities of an organisation, by integrating socially responsible principles and concerns of stakeholders in operations in a manner that fulfils and exceeds current legal and commercial expectations. Corporate social performance (CSP) has extended the responsibility of the organisation's management, which shifts from being a mere agent of shareholders to being the guarantor of every stakeholder's satisfaction (De Quevedo-Puente, De la Fuente-Sabaté & Delgado-García 2007:62). Evaluating CSP is important for stakeholders employing social performance information in their decision-making models (Ruf, Muralidhar & Paul 1998:119). Without attention to principles of social responsibility and actual outcomes experienced by stakeholders, social policies are not likely to be institutionalised in organisations (Van Buren 2005:687). Managers concerned about their organisation's social performance must undertake a social audit. Seep Network (2007:1) describes a social audit as the evaluation of social performance externally. There are many stakeholders that have to be consulted when doing this audit such as the owners and investors, customers, employees and the community. Measuring and reporting on social performance is a key measure for triple bottom line organisations to define the social value they create, while holding themselves accountable for the goals articulated in their mission (Reddy 2007:5). Given the lack of information available on the extent to which South African SMEs evaluate CSP, it is thus imperative to research this issue.

Firstly, the problems statement is highlighted, followed by the objectives of the article. Thereafter the literature study on CSP follows. The hypotheses are outlined with an explanation of how they are identified. The research methodology outlines how the study was conducted followed by the results with the implications and recommendations derived from the results. Lastly, guidelines for evaluating corporate social performance and taking care of stakeholder concerns are given.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

Managers have many responsibilities, which engage them in a wide range of activities (Hellriegel et al 2006:124). Furthermore, these activities can be grouped according to the people who are affected by these decisions. This means that a manager's job can be thought of as a series of attempts to address the concerns of various stakeholders. The corporate social responsibility concept became popular because multi-national organisations wanted to anticipate government regulations, which was outlined in the King I Report in 1994 (Asongu 2007:13; Rossouw 2002:409).

The King II Report was published in 2002 and focus not only on the inclusive stakeholder approach but also assigned responsibility for the corporate governance of ethics to the board of directors (Rossouw 2002:409). The King II Report recommends that organisations report on the triple bottom-line and not on financial performance only (Minaar-van Veijeren 2002:1). The triple bottom line attempts to review the three components of sustainability, namely economic, social and environmental (Carroll & Buchholtz 2006:57). The notion of the triple bottom line, according to Hellriegel et al (2006:128) is that organisations must disclose their social and environmental performance in conjunction with their financial performance. A survey conducted by KPMG founded that South Africa's levels of corporate sustainability ranked last of 19 countries surveyed. Only 1% of South Africa's top 100 companies produce separate reports on triple bottom line issues. If this is true about larger organisations, it needs to be established to what extent SMEs are involved in triple bottom line issues, especially in social performance reporting. This led to the following question to be addressed in this research study: To which extent do SMEs in the Nelson Mandela Metropole evaluate corporate social performance and take care of stakeholder concerns?

OBJECTIVES

The primary objective of this article is to investigate the extent to which SMEs evaluate corporate social performance in the Nelson Mandela Metropole. To help achieve this objective, the following secondary goals are identified:

• To highlight the nature of corporate social performance.

• To provide an overview of stakeholder concerns when evaluating corporate social performance.

• To empirically assess the extent to which SMEs evaluate social performance in the Nelson Mandela Metropole.

• To provide general guidelines for SMEs on how to evaluate social performance.

In the next section, a literature overview of CSP is provided.

EVALUATING CORPORATE SOCIAL PERFORMANCE: A LITERATURE OVERVIEW

Concept clarification

Orlitzky (2000:5-6) defines corporate social performance (CSP) as a business's configuration of principles of social responsibility, processes of social responsiveness, and policies, programs, and observable outcomes as they relate to the business's societal relationships. Furthermore, it applies to any organisation and is built on the principles of corporate social responsibility. Simerly (2003:1) used the definition provided by Carroll (1979) and describes CSP as the identification of the domains of an organisation's social responsibility, the development of processes to evaluate environmental and stakeholder demands and the implementation of programs to manage social issues. Sustainability refers to economic development that generates wealth and meets the needs of the current generation while saving the environment so future generations can meet their needs as well (Daft 2008:154).

How to evaluate CSP

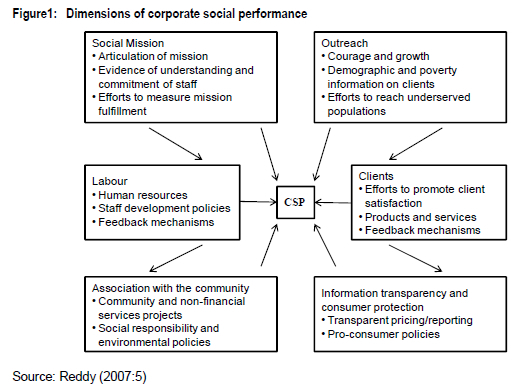

Nel (2002:74) states that understanding CSP requires researchers and communication managers to develop an approach that can show the value of CSR, the performance of the organisation regarding these responsibilities and the financial impact of responding to these responsibilities. Reddy (2007:5) identifies the various dimensions of social performance as shown in Figure 1.

Although some of the dimensions are included in this study, the five categories of obligations to evaluate CSP as identified by Hellriegel et al. (2004:138-139) were utilised: broad performance criteria; ethical norms; operating strategy; response to social pressures, and legislative and political activities. These five categories are discussed below.

• Broad performance criteria

An organisation should set targets for social performance goals and regularly presents key indicators and other indicators relevant to social performance to its board (Justmeans.com 2004:1). The broad performance criteria state that managers and employees must consider and accept broader criteria for measuring their performance to include activities not only required by legislation and the marketplace, but by measuring their social role (Hellriegel et al 2004:128). It is suggested that a dual bottom line with economic and non-economic criteria be followed, requiring multiple objectives, for example evaluate employees in terms of financial- and social contribution to the community (Lantos 2001:601).

• Ethical norms

Business ethics is a form of the art of applied ethics that examines ethical principles and moral or ethical problems that can arise in a business environment (Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 2009:1). Ethnic performance requires responsibility in seeking to do what is right (Peery 2008:814). Employees and managers must also speak out on issues that concern the public, even when other organisations are not following the same practices or if this seems advantageous to the organisation's bottom line (Hellriegel et al. 2004:128). Natale and Ford (1994:31) recommend that a social audit be used as a corrective "ethics check list". Furthermore, a review of the social audit can become the value-added groundwork for the organisation's ethical concern.

• Operating strategy

Waddock and Graves (1997:2) regard corporate social performance as being integrally related to the organisation's daily operating practices, with respect to primary stakeholders, who are the most affected by the organisation's activities. Organisations need to re-evaluate their operating strategy to ensure that victims of pollution or other hazards are compensated and that negative effects resulting from the organisation's operations are reduced (Hellriegel et al 2004:128). On the other hand, Fraser (2005:2) indicates that organisations that recognize the fact that their value is made up of "good will" will take appropriate steps to minimize negative impacts on stakeholders to protect their valuable reputations and goodwill.

• Response to social pressures

Organisations never exist in isolation - it is embedded in a wide web of relationships (Roussouw & Van Vuuren 2004:26). Therefore, it is important to accept responsibility for solving problems through discussions with outside stakeholders to involve them in decision-making processes (Hellriegel et al 2004:128). Orlitzky (2000:7) identified three corporate social responsiveness mechanisms: environmental assessment by scanning the environment to respond or adapt to business environment conditions; stakeholder management e.g. devices such as employee newsletters, public affairs offices, and community relations programmes; and issues management, which is the process of identifying important social issues, evaluate their potential impact on the organisation, develop objectives and formulate and implement a strategic response to influence the levels of corporate legitimacy in public policy processes (Peery 2008:824).

• Legislative and political activities

Peery (2008:814) regards legality as compliance with laws and regulations that apply to the organisation's situation and legitimacy as sensitivity to the political context of the situation so that political and social support necessary for a favourable business environment can be maintained. Managers must encourage honesty and openness with both the government and their own organisations, as they willingly work together with outside stakeholders (Hellriegel et al 2004:128). Natale and Ford (1994:30) suggest two different types of social audits, one being required by government and the other programmes voluntarily taken on by an organisation. The social audit required by government created bureaucracies such as the Environmental Protection Agency, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, The Consumer Product Safety Commission and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. An organisation's social performance is judged largely by how it addresses stakeholder relationships and issues (Logsdon & Yuthas 1997:1213). Caroll and Buchholtz (2006:57-58) find that there is a relationship between CSP and stakeholders "multiple bottom line". The next section outlines stakeholders involved when evaluating corporate social performance.

Stakeholders involved when evaluating corporate social performance

Stakeholders can be defined as groups or individuals who have an interest in the actions of an organisation and the ability to influence it (Gao & Zhang 2006:724). Peery (2008:821) describes stakeholders as any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organisation's objectives. The role of stakeholders in relation to the organisation is to: set expectations; experience effects; evaluate outcomes; and act on these evaluations (Neville, Bell & Mengüç 2005:1186). Fraser (2005:1) recognises the link between corporate social responsibility and the impact it has on multiple stakeholders. Jamali (2007:213), Sen, Bhattacharya and Korschun (2008:158) and Werther and Chandler (2005:317) highlight the usefulness of a stakeholder approach to corporate social performance in light of its practicality for both managers and scholars and to optimise stakeholder returns over the long-term. Four stakeholder groups are discussed in this article.

Employees can be defined as any individual actually employed by an organisation or whose work directly affects and relates to core economic functions of the organisation (Van Buren 2005:693). In terms of employees, two major areas of concern are the work that they perform and the pay that they receive (Hellriegel et al 2006:125). CSP evaluation for employees can be in terms of non-discriminatory, merit based hiring and promotion; diversity of the workforce; wage and salary levels and equitable distribution; workplace safety and privacy and the availability of training and development (Brammer & Pavelin 2006:441; Clarkson 1995:99 & Hellriegel et al 2004:128).

Customers require organisations to improve the quality of their products while keeping their costs at a minimum. Some customers also only purchase from organisations that have a reputation for implementing CSP (Hellriegel et al 2006:124). Customers concerns should be evaluated in terms of product/service quality, innovativeness and availability; responsible management of defective or harmful products/services; safety records for products/services; pricing policies and practices; and honest, accurate and responsible advertising (Clarkson 1995:99).

Owners/investors and shareholders invest their money for financial objectives and this result in greater power to influence the decisions of management (Hellriegel et al (2004:128). Furthermore it is recommended that concerns of owners and investors should be evaluated in terms of financial soundness; consistency in meeting shareholders' expectations; sustained profitability; average return on assets over a five-year period; and timely and accurate disclosure of financial information. Simerly and Li (2000:2) are of the opinion that the primary purpose of the organisation to maximise shareholders' wealth has being replaced by the purpose to satisfy needs within society.

Hellriegel et al (2004:128) and Clarkson (1995:102) suggest that community concerns should be evaluated in terms of: environmental issues (such as environmental sensitivity in packaging and product design; recycling efforts and use of recycle materials; pollution prevention; global application of environmental standards); and community involvement (such as percentage of profits designated for charitable contributions; innovation and creativity in philanthropic efforts; product donations; availability of facilities and other assets for community use and support for employee volunteer efforts).

Environmental concerns can also be evaluated in terms of quality of environmental policies, systems, reporting and performance (Brammer & Pavelin 2006:441). Waddock and Graves (1997:2) regard social performance not just as philanthropy or volunteerism but also in terms of the treatment of stakeholders. The evaluation criteria stakeholders use to judge an organisation's reputation will differ depending on particular stakeholder's expectations of the organisation's role (Neville et al 2005: 1188). Furthermore, these expectations can change over time as the organisation's reputation increases. Sustainable development of organisations can only take place if taking into consideration stakeholder concerns. Gao and Zhang (2006:724) regards stakeholder engagement as critical in develop, albeit limited, both semi-proactive and proactive stances towards sustainability. Epstein (2008:24) further urged organisations to choose a sustainability strategy that is aligned with stakeholder requirements.

Sustainable development

If an organisation takes into consideration societal and environmental concerns by protecting the natural environment while still progressing economically, it is known as sustainable development (Hellriegel et al 2004:125). With a philosophy of sustainability, managers weave environmental and social concerns into every strategic decision, revise policies and procedures to support sustainability efforts, and measure their progress toward sustainability goals (Daft 2008:154). Corporate sustainability is an ideology for rethinking organisations beyond corporate social and/or environmental responsibility activities towards holistic corporate sustainability, requiring systemic corporate cultural changes (Gao & Zhang 2006:724). The organisation's survival and continuing success depend upon the ability of its managers to create sufficient wealth, value or satisfaction for those who belong to each stakeholder group (Clarkson 1995:107). The four key components of corporate sustainability are: the triple bottom line; stakeholder's engagements; accountability; and sustainable reporting (Gao & Zhang 2006:724). If any primary stakeholder group perceives, over time, that it is not being treated fairly it will withdraw from the system and threaten the organisation's survival (Clarkson 1995:112). Gao and Zhang (2006:735) suggest a match between corporate sustainability and social auditing, as both are aimed at improving the performance of an organisation socially, environmentally and economically. Effective risk management will ultimately lead to greater prevention of fraud and mismanagement and to higher organisational stability and sustainability (Minaar-van Veijeren 2002:1). According to Gao and Zhang (2006:724), sustainable development can only be given real meaning and achieved through a multi-stakeholder approach. Although social performance measurement and reporting is a relatively well-established practice among a few leading edge organisations, for many smaller SMEs integrating the environmental and social attainments into the economic performance of a SME is at an early stage or has not started yet. Furthermore, the ongoing relationship between the organisation and its stakeholders provides feedback to business decision makers and other parties interested in CSP (Van Buren 2005:692).

Based on the above theoretical overview of CSP and stakeholder concerns, eight null-hypotheses were formulated using perceptions regarding social performance obligations and sustainability as independent variables and stakeholder concerns as dependent variables.

H01: There is no relationship between perceptions of SMEs corporate social performance obligations and owners' concerns.

H02: There is no relationship between perceptions of SMEs corporate social performance obligations and customers' concerns.

H03: There is no relationship between perceptions of SMEs corporate social performance obligations and employees' concerns.

H04: There is no relationship between perceptions of SMEs corporate social performance obligations and communities' concerns.

H05: There is no relationship between SMEs sustainable development perceptions and owners' concerns.

H06: There is no relationship between SMEs sustainable development perceptions and customers' concerns.

H07: There is no relationship between SMEs sustainable development perceptions and employees' concerns.

H08: There is no relationship between SMEs sustainable development perceptions and communities' concerns.

The research hypotheses (H1 to H8) could be stated as the exact opposite of the above-mentioned null-hypotheses, indicating that there are significant relationships between the dependent variables (stakeholder concerns) and independent variables (perceptions regarding corporate social performance).

Influence of demographics on evaluating social performance

Roberts, Lawson and Nicholls (2006:275) are of the opinion that certain demographical characteristics of SMEs tend to reduce their interest and opportunities for engaging in social performance activities. Salk and Arya (2005:189) concur that due to the pressures of globalisation, organisations are confronted by complex challenges to continuously achieve higher levels of social performance across diverse country and cultural contexts. Frooman and Murrell (2005:3) and De Bakker and Den Hond (2008:8) further postulate that demographical variables appear to influence the repertoire of strategies that stakeholders select to exert influence on an organisation. According to Panwar, Han and Hansen (2009), "understanding the perceptions and expectations of various demographic segments about business performance along relevant social and environmental issues is a research gap in the broader field of corporate social responsibility." This knowledge gap is important to be filled, as it may assist industry managers to formulate effective CSP strategies and policies and also to enrich the academic knowledge about CSP. Varying degrees of differences were found in different demographical categories such as gender, educational level and age. McWilliams and Siegel (2001:117) also hypothesize that an organisation's level of CSP will depend on its size, level of diversification and consumer income. Despite these arguments, Williams (2005) alleges that there is little evidence that demographic factors affect social performance. Carpenter (2002:275) contends that empirical results regarding demographical differences are often ambiguous. Reagans, Zuckerman and McEvily (2004:101) state that this ambiguity in organizational demography literature is due to the fact that demographic diversity in an organisation often leads to a wide range of opinions - however the implications of managing social performance should be clear.

Several specific organisational characteristics serve as data classification (independent) variables in this study. These include type of industry; employment sector and size; hierarchical position; income and extent of corporate social performance reporting. A total of 36 null-hypotheses were formulated, however, only those independent variables that show significant relationships with the dependent variables (perceptions regarding corporate social performance and stakeholder concerns) are reported. Based on this reasoning, the following four null-hypotheses are formulated:

H09: There is no relationship between sustainable development perceptions and the income of SMEs.

H010: There is no relationship between sustainable development perceptions and the extent of SMEs corporate social performance reporting.

H011: There is no relationship between employee concerns in terms of corporate social performance and the extent of SMEs corporate social performance reporting.

H012: There is no relationship between community concerns in terms of corporate social performance and the extent of SMEs corporate social performance reporting.

No specific relationships were found between the other dependent variables (social performance obligations, owner and customer concerns and the independent variables (type of industry, economic sector, employment size and position in the organisation). Only those variables that indicated a significant relationship are reported here in the above-mentioned hypotheses.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

To investigate the perceptions of evaluating corporate social performance and concerns for stakeholders, an empirical study was undertaken.

Research approach

The quantitative research method is used in this study. It is a form of conclusive research, which involves a large representative sample and structured data collection procedures are used. The quantitative research approach used is descriptive research (perceptions of evaluating corporate social performance and stakeholder concerns).

The sample

It is difficult to establish the total population for this study, as there is no database available of SMEs that evaluate CSP or are knowledgeable on CSP. In spite of this drawback the population can be regarded as all SMEs in the Nelson Mandela Metropole possibly involved in some form of corporate social performance evaluation or being knowledgeable on CSP. The sample had to meet the following criteria:

• Situated in the Nelson Mandela Metropole;

• SMEs knowledgeable on or involved in CSP;

• Employment size of less than 50 employees (representing the small business sector) and 50 but less than 200 employees (representing the medium-sized business sector). As there are wide variances with regard to turnover and asset value of SMEs, it will not be used as criteria in this study.

Fieldworkers have approached SMEs and conduct the research. To avoid duplication, SMEs were required to attach a business card to the completed questionnaires.

Data collection

During the literature search (secondary data collection), various textbooks, journals and the Internet were consulted. Primary data was collected by means of a survey through self-administered questionnaires. Of the 250 questionnaires distributed, a total non-probability sample of 228 was obtained (convenient sample) which indicates a response rate of 91%. Some questionnaires were discarded due to duplication or incompleteness.

The questionnaire

Self-administered questionnaires were used. The questionnaire is divided into three sections:

• Section A deals with perceptions of evaluating corporate social performance and consists of two factors, namely categories of obligation toward social performance (five variables) and aspects of sustainable development of organisations (six variables). A total of eleven variables/statements are used. The type of ordinal scale used is a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

• Section B investigates the concerns of stakeholders when evaluating corporate social performance. Four factors (stakeholder groups) are tested, namely owners and investors; customers; employees and community. A total of 20 variables/ statements are used. An ordinal type of scale is used by means of a five-point Likert-type scale.

• Section C provides classification data (demographic characteristics) of respondents and contains a nominal scale of measurement, using six categorical variables.

Pilot study

In order to pre-test the questionnaire, it was given to a few SMEs and academics in the field of management, ethics and statistics. After processing and analysing the data from this pilot study, the questionnaire was refined and some minor changes were made regarding wording, sequence and layout.

Data processing and analysis

The returned questionnaires were inspected to determine their acceptability, edited where necessary, and coded. The data were transferred to an Excel spreadsheet. A statistical computer package, named SPSS-PC, was used to process the results.

Techniques used during data analysis included descriptive statistics (e.g. mean and standard deviation), frequency distributions, correlation coefficients and analysis of variance.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Demographical profile of respondents

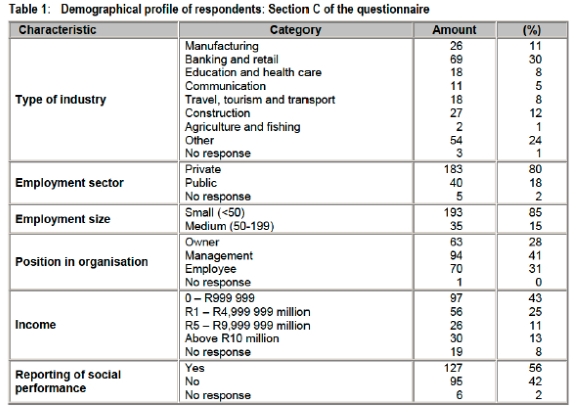

Table 1 provides a demographical profile of the respondents of this study.

From the results in Table 1 it is clear that most of the respondents are active in the banking and retail industry (30%) and construction industry (12%) respectively. Eighty percent of the respondents are employed in the private sector whilst only 18% are employed in the public sector. The employment size of the majority of the respondents (85%) is small (less than 50 employees) while 15% is employed in medium-sized organisations (between 50 and 199 employees). Most of the respondents (41%) are in managerial positions in the organisation with the least being owners (28%). Thirty one percent of the respondents were employees of their respective organisations. It appears that 43% of the respondents are employed in organisations with an annual income of less than one million rand while 13% have organisations with income in excess of ten million rand. It was interesting to notice that only 56% of the sample organisations do report on social performance whilst a relative large group of 42% do not report on social performance.

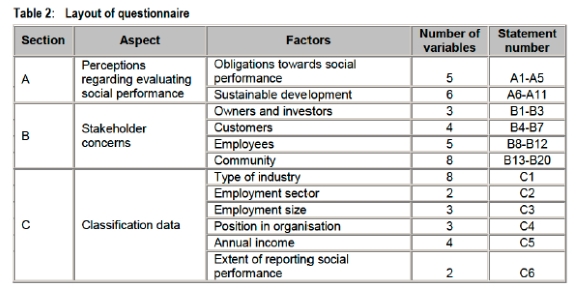

Variables used in the survey

Table 2 provides a layout of the factors and variables used in the questionnaire, which will be used for the analyses and discussion of the research results.

Descriptive statistics

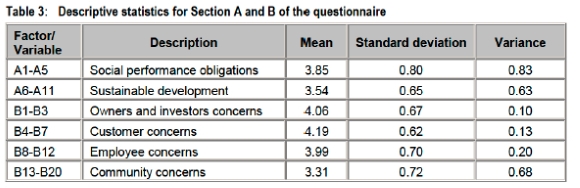

Table 3 provides an overview of the most important and significant descriptive statistics for Section A (perceptions regarding evaluating corporate social performance) and Section B (stakeholder concerns) of the questionnaire.

In analysing the measure of central tendency (mean values) for the factors used in Section A and B of the questionnaire, it appears that most values cluster around point four of the scale (agree), except for the factor regarding community concerns (respondents tend to be neutral towards this factor). Measures of dispersion, by means of low standard deviation and variance scores, indicate that respondents tend not to vary much regarding the factors tested in these sections of the questionnaire. The highest standard deviation (0.80) and variance score (0.83) were obtained for social performance obligations, indicating that the respondents tended to vary most in their responses for this factor.

Reliability and validity of the measuring instrument

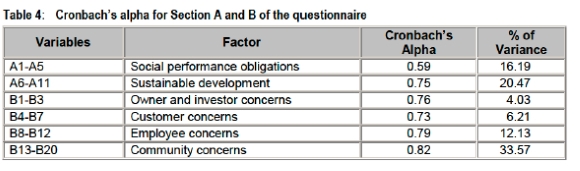

External validity is ensured by means of a proper and sound sampling procedure. Attention was given to ensure that the questionnaires were completed at the appropriate time and place and under conditions conducive for accurate research. Internal validity of the instrument's scores is ensured through both face and content validity. Expert judgment and a pilot study were undertaken to assist in this regard. The statistical software package, SPSS, was used to determine the Cronbach's alpha values for the two predetermined factors of Section A of the questionnaire (perceptions regarding evaluating social performance) and four predetermined factors of Section B (stakeholder concerns). To confirm the internal reliability of these six factors, Cronbach's alpha was calculated (refer to Table 4).

To establish the reliability of the various factors, Cronbach's alpha was calculated (indicating internal consistency). The reliability coefficients of Cronbach's alpha for the various factors are all above 0.7, except for the social obligations factor (0.59). According to Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black (1998:118), Cronbach's alpha value may be decreased to 0.6 In exploratory research. It can therefore be concluded that all factors are internally reliability. The tabled percentage of variance, as presented in Table 4, Is the percentage of variance (of the items constituting each factor). The community concerns factor obtained the highest percentage of variance (33.57%).

Correlation

An inter-item correlation exercise was conducted to determine the correlation between the variables constituting each factor in Section A (social performance obligation and sustainability variables) and Section B (stakeholder concerns) respectively. A detailed presentation of the correlation matrix results, fall beyond the scope of this article. It can however, be reported that all the variables in each factor show positive relationships with each other (ranging from the strongest positive r-value of 0.5540 to the lowest positive r-value of 0.0357). A positive correlation coefficient (r-value) indicates a strong or positive relationship among the variables. No negative r-values are reported.

ANOVA

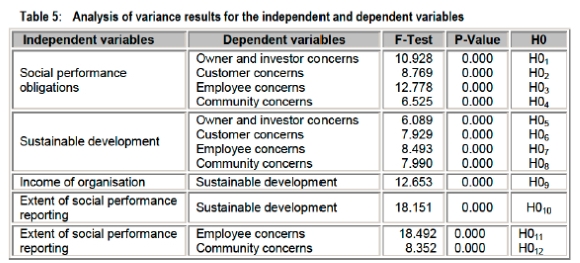

The purpose of this analysis is to investigate the relationship between the independent and dependent variables and to test the stated hypotheses. Table 5 provides an outline of the variables used in this analysis. Inferential statistics are used to make inferences about the population using sample data to make decisions regarding various hypotheses. Different analyses of variance exercises were conducted to test the stated hypotheses. Only those ANOVA results that show significant relationships between the independent and dependent variables are reported and those that exhibit no significant relationships are excluded from this discussion. The first ANOVA exercise investigated the relationship between stakeholder concerns (dependent variables) and social performance obligations and sustainability (independent variables). The second ANOVA exercise investigated the relationship between social performance obligations, sustainability, stakeholder concerns (dependent variables) and classification data (independent variables).

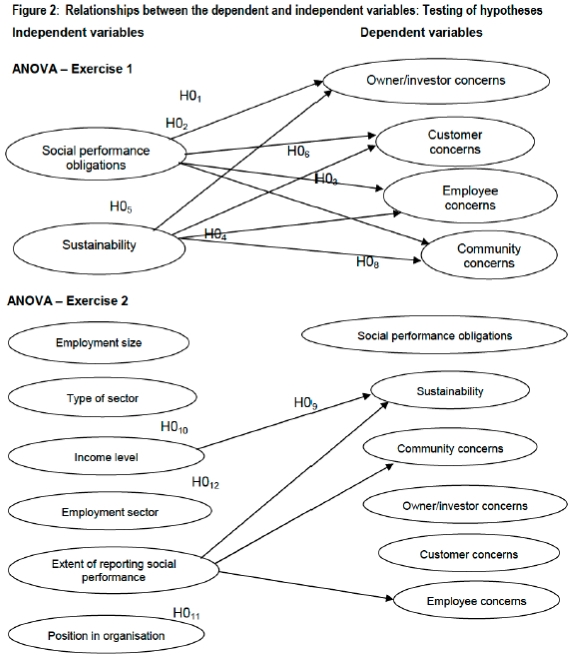

The ANOVA results clearly indicate the relationships between the independent and dependent variables. The null-hypotheses (H01 to H012) can, in all cases, be rejected at a significance level of 0.01 and the alternative hypotheses can be accepted. H01 to H08 fall within the rejection region (p < 0.01 and large F-statistic values), which indicate that there is a significant relationship (difference) between the perceptions regarding evaluating social performance and stakeholder concerns (H1 to H8 can be accepted which indicate that there are significant relationships between the tested variables). The null hypotheses, H09 to H012, are also rejected at a significant level of 0.01 (P-value is 0.000 and high F-statistic values). There are highly significant relationships or differences between sustainable development and the independent variables: income and extent of social performance reporting (H9 and H10 accepted). Community and employee concerns also showed highly significant relationships with the independent variable, extent of social performance reporting (H11 to H12 accepted). No relationships exist between owners' and customers' concerns and the independent variables (classification data). From the above results, one can therefore construct the following model, as depicted in Figure 2, to indicate the different relationships between the dependent and the independent variables. Those variables that are not linked to any of the variables thus indicate no relationships.

As significant differences between mean values were found, further post-hoc tests (such as the Scheffé's test) were conducted as to identify where the differences occur, but are not reported, as it falls beyond the scope of this article.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

There appears to be highly significant relationships between the perceptions regarding corporate social performance and taking care of stakeholder concerns. Perceptions about obligations when evaluating social performance and sustainable development are positively correlated with taking care of owners, customers, employees and community concerns (H01 to H08 rejected). SMEs should strive to adopt a proactive or affirmative approach to social responsibility by accepting the following obligations: broader social performance criteria than required by law; ethical norms by taking stands on issues of public concern; implementing strategies to improve the physical environment; responsiveness to social pressures and obeying environmental protection laws. Besides accepting these obligations, organisations should also endeavour to incorporate the principles of long-term sustainability and the triple bottom line in its operations. SMEs should disclose their social and environmental performance alongside their financial performance. It implies responsible development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The aim should be to engage in good corporate citizenship and improvement of risk management practices so as to enhance sustainability. By accepting and practising these obligations and sustainable development principles, SMEs would be more responsive towards the concerns and needs of owners/investors, customers, employees and the community. These stakeholder groups benefit from SMEs successes and can be harmed by its failures and mistakes. SMEs have thus an interest in maintaining the general well-being and effectiveness of these stakeholder groups.

The following conclusions and recommendations can be drawn, based on the analysis of variance of the independent variables (classification data) and dependent variables (sustainable development and stakeholder concerns) used in this research project:

• There appears to be a highly significant relationship between the perceptions regarding sustainable development and the following classification data variables: income and extent of social performance reporting (H09 to H010 rejected). No relationships exist between perceptions regarding social performance obligations and the classification data variables. SMEs with different income levels have different perceptions regarding sustainable development. SMEs, which do report on social performance, will have different perceptions of sustainability as those, which do not report on social performance. It is recommended that even smaller organisations with lower income levels, which often struggle for survival and making profits, should strive towards long-term sustainable development. The focus should not only be on reporting financial performance, but also on social and environmental performance. It thus appears that type of sector, employment sector, employment size and position in the organisation is not related to perceptions about sustainability of SMEs.

• The extent to which SMEs report on social performance, or not, is directly related to taking care of employee and community concerns (H011 and H012 rejected). Those SMEs that do report on social performance take care of employee and community concerns differently as compared to those that do not report on social performance. It is advisable that all SMEs should report on social performance along with financial performance and should take care of the needs and concerns of all stakeholder groups.

• It was interesting to note that there were no relationships between the independent variables (classification data) and taking care of owners/investors and customer needs. Based on the classification data variables, SMEs seem to be indifferent towards taking care of owner and customer needs or concerns. This might be an indication of poor customer services provided by SMEs and often reported by customers. Customer concerns to be taken care of could include: product quality and innovativeness, management of defective or harmful products and honest and accurate advertising.

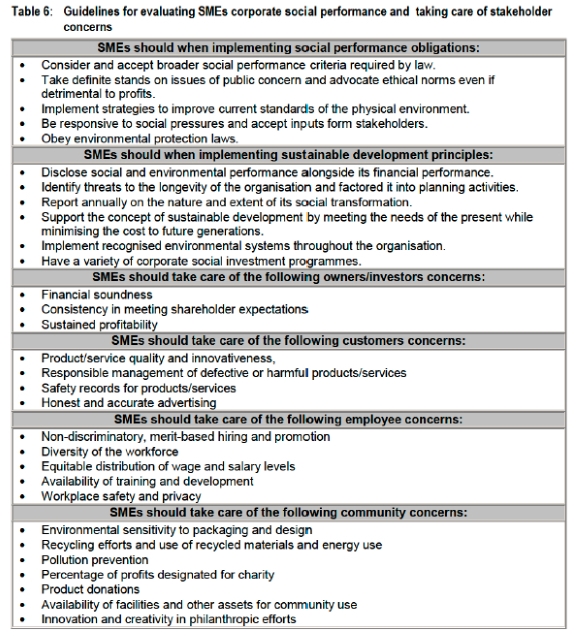

Table 6 provides some general guidelines for evaluating SMEs corporate social performance and taking care of stakeholder concerns.

LIMITATIONS

It was unfortunate that no database was available to determine the total population. Some of the smaller SMEs could have been in the informal sector and not registered. There are variances in the employment size within the small business sector (less than 50 employees), and therefore the smaller of these businesses (with less than five employees) might have other limitations preventing participation in CSP. The study was only limited to SMEs in the Nelson Mandela Metropole which is situated in the Eastern Cape and is regarded as one of the poorest provinces.

The following extract serves as an appropriate conclusion to this article:

"... for a corporate social responsibility initiative to lead to a sustainable first-mover advantage, it must be central to the firm's mission, provide firm-specific benefits, and be made visible to external audiences. These strategic attributes generate internal sustainability and must be complemented to ensure external defensibility by a firm's ability to assess its environment, manage its stakeholders, and deal with social issues."

(Sirsly & Lamertz 2008:243)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ASONGO J.J. 2007. The history of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business and Public Policy, 1(2): 1-18. [ Links ]

BRAMMER S.J. & PAVELIN S. 2006. Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. Journal of Management studies, 43(3):339-44. [ Links ]

CARPENTER M.A. 2002. The implications of strategy and social context for the relationship between top management heterogeneity and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23(3):275-284. [ Links ]

CARROLL A.B. & BUCHHOLTZ A.K. 2006. Organisation and Society: Ethics and stakeholder management. 6th edition. Ohio: Thomson. [ Links ]

CLARKSON M.B.E. 1995. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1):92-117. [ Links ]

DAFT R. 2008. The new era of management. 2nd edition. United States: Thomson South-Western. [ Links ]

DE BAKKER G.A. & DEN HOND F. 2008. Introducing the politics of stakeholder influence. Business & Society, 47(1):8-20. [ Links ]

DE QUEVEDO-PUENTE E., DE LA FUENTE-SABATÉ J.M. & DELGADO-GARCÍA J.B. 2007. Corporate social performance and corporate reputation: Two interwoven perspectives. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(1): 60-72. [ Links ]

ENGAGEWEB.ORG. 2008. Defining social responsibility. [Internet: www.engageweb.org/whatdefining.htm; downloaded on 2008-08-30. [ Links ]]

EPSTEIN M.J. 2008. Best practices in managing and measuring corporate social, environmental and economic impacts. UK: Greenleaf Publishing. [ Links ]

FRASER B.W. 2005. Corporate social responsibility: Many of today's corporate stakeholders are calling for increased sustainable development. [Internet: www.findarticles.com; downloaded on 2008-02-15. [ Links ]]

FROOMAN J. & MURRELL A.J. 2005. Stakeholder influence strategies: The roles of structural and demographical determinants. Business & Society, 44(1):3-31. [ Links ]

GAO S.S. & ZHANG J.J. 2006. Stakeholder engagement, social auditing and corporate sustainability. Business Process Management Journal, 12(6):722-740. [ Links ]

HAIR J.F., ANDERSON R.E., TATHAM R.L. & BLACK W.C. 1998. Multivariate data analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc. [ Links ]

HELLRIEGEL D., JACKSON S.E., SLOCUM J. STAUDE G. & ASSOCIATES. 2006. Management. 2nd edition. Cape Town: Oxford. [ Links ]

HELLRIEGEL D., JACKSON S.E., SLOCUM J., STAUDE G. & ASSOCIATES. 2004. Management. 1st edition. Cape Town: Oxford. [ Links ]

JAMALI D. 2007. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility: A fresh perspective into theory and practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(1):213-231. [ Links ]

JUSTMEANS.COM. 2004. How to evaluate corporate social performance. [Internet: www.justmeans.com/usercontent/companydocs/docs; downloaded on 2009-05-28. [ Links ]]

LANTOS G.P. 2001. The boundaries of strategic corporate social responsibility. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(7):595-630. [ Links ]

LOGSDON J.M. & YUTHAS K. 1997. Corporate social performance, stakeholder orientation, and organisational moral development. Journal of Business Ethics, 16:1213-1226. [ Links ]

MCWILLIAMS A. & SIEGEL D. 2001. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 26(1):117-127. [ Links ]

MINNAAR-VAN VEIJEREN J. 2002. The King II report on corporate governance. [Internet: www.i-value.co.za/king.html; downloaded on 2009-06-02. [ Links ]]

MONEVA J.M., RIVER-LIRIO J.M. & MUÑOZ-TORRES M.J. 2007. The corporate stakeholder commitment and social and financial performance. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 107(1):84-102. [ Links ]

MURILLO D. & LOZANO J.M. 2006. SMEs and CSR: An approach to CSR in their own words. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(3):227-240. [ Links ]

NATALE S.M. & FORD J.W. 1994. The social audit and ethics. Managerial Accounting Journal, 9(1):29-33. [ Links ]

NEL P. 2002. Understanding and measuring corporate social performance: A multidimensional approach. Communicare, 21(2):74-75. [ Links ]

NEVILLE B.A., BELL S.J. & MENGÜÇ B. 2005. Corporate reputation, stakeholders and the social performance-financial performance relationship. European Journal of Marketing, 39(9/10):1184-1198. [ Links ]

ORLITZKY M. 2000. Corporate social performance: developing effective strategies. Sydney: Centre for corporate change. [ Links ]

PANWAR R., HAN X. & HANSEN E. 2009. A demographic examination of societal views regarding corporate social responsibility in the US forest products industry. [Internet: www.sciencedirect.com; downloaded on 2009-11-11. [ Links ]]

PEERY N.S. 2008. Corporate Social Performance: Ethics and Corporate culture. [Internet: www.mcgeorge.edu/Documents/publications; downloaded on 2009-05-29. [ Links ]]

PERRINI F. 2006. SMEs and CSR Theory: Evidence and implications for an Italian perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(3):305-316. [ Links ]

REAGANS R., ZUCKERMAN E. & MCEVILY B. 2004. How to make the team: Social networks vs. Demography as criteria for desiogning effective teams. Adminsitartive Science Quarterly, 49(1):101-133. [ Links ]

REDDY R. 2007. Guidelines to evaluate social performance. [Internet: www.publications.accion.org/publications/Insight_24.230.asp; downloaded on 2009-05-28. [ Links ]]

ROBERTS S., LAWSON R. & NICHOLLS J. 2006. Generating regional-scale improvements in SME corporate responsibility performance: Lessons from Northwest England. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(3):275-286. [ Links ]

ROSSOUW D. & VAN VUUREN L. 2004. Business Ethics. 3rd edition. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

ROSSOUW G.J. 2002. Business ethics and corporate governance in the Second King Report: Farsighted or futile? Koers, 67(4):405-419. [ Links ]

RUF B.M., MURALIDHAR K. & PAUL K. 1998. The development of a systematic, aggregate measure of corporate social performance. Journal of Management, 24(1):119-133. [ Links ]

SALK J.E. & ARYA B. 2005. Social performance learning in multinational corporations: Multicultural teams, their social capital and use of cross-sector alliances, Advances in International Management, 18:189-207. [ Links ]

SANG J. 2008. An analysis of corporate social responsibility for small and medium-sized enterprises. Service Operations and Logistics and Informatics. 1:337-341. [ Links ]

SEEP NETWORK. 2007. Social Performance assessment. Social Performance progress brief, 1(3). [Internet: www.lamicrofinance.org/files; downloaded on 2009-06-05. [ Links ]]

SEN S., BHATTACHARYA C.B. & KORSCHUN D. 2008. The role of social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: Afield experiment. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2):158-166. [ Links ]

SIMERLY R.L. & LI M. 2000. Corporate social performance and multinationality: A longitudinal study. [Internet: www.westga.edu/~bquest/2000/corpoate.html; downloaded on 2009-05-28. [ Links ]]

SIMERLY R.L. 2003. An empirical examination of the relationship between management and corporate social performance. International Journal of Management, 1 September 2003. [Internet: www.findarticles.com; downloaded on 2009-06-02. [ Links ]]

SIRSLY C.T. & LAMERTZ K. 2008. When Does a Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Provide a First-Mover Advantage? Business & Society, 47(3):343-369. [ Links ]

THERON D. 2005. Corporate social responsibility: A Pharmaceutical industry analysis. Acta Commercii, 5:1-12. [ Links ]

VAN BUREN H.J. 2005. An employee-centered model of corporate social performance. Business Ethics Quarterly, 15(4):687-709. [ Links ]

WADDOCK S. & GRAVES S. 1997. Finding the link between stakeholder relations and quality of management. [Internet: www.Socialinvest.org/pdf/research/Moskowitz/1997; downloaded on 2009-08-16. [ Links ]]

WERTHER W.B. & CHANDLER D. 2005. Strategic corporate social responsibility as global brand insurance. Business Horizons, 48(4):317-324. [ Links ]

WIKIPEDIA THE FREE ENCYCLOPEDIA. 2009. Corporate social responsibility. [Internet: www.wikipedia.org; downloaded on 2009-08-16. [ Links ]]

WILLIAMS G. 2005. Some determinants of the socially responsible investment decision: A cross country study. [Internet: ssm.com/abstract=905189; downloaded on 2009-11-11. [ Links ]]