Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

BBBEE ownership issues in Cape Peninsula-based advertising agencies: a multiple case study approach

RG Duffett

Marketing Department, Cape Peninsula University of Technology

ABSTRACT

The advancement of transformation has been a protracted and complex process, but the South African (SA) government has made some degree of progress with the gazetting of Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) legislation over the past decade. The SA advertising industry received criticism for its sluggish transformation progress, which led to allegations of racism in the early 2000s. Consequently, the main purpose of this study is to examine the benefits and challenges emanating from the Cape Peninsula-based advertising agencies' efforts to attain the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) Codes of Good Practice (Codes) scorecard and Marketing, Advertising and Communication (MAC) transformation charter ownership targets. The multiple case study approach was applied and a semi-structured interview guide was used to extract a wealth of data from the Cape Peninsula advertising industry. The results revealed numerous problems and benefits as a consequence of the agencies deliberate attempts to achieve the targets.

Key phrases: Advertising agencies, Cape Peninsula advertising industry, Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE) ownership, multiple case study, transformation charters

INTRODUCTION

BEE began in the early 1990s when several large corporations sold stakes to Black empowerment syndicates. Few of these pioneering BEE deals were successful; however, essential principles were revealed with respect to how BEE agreements should work (Coulsen 2004:19-20). BEE aims to encourage economic transformation by eliminating unfair discrimination; applying affirmative action (AA) policies; empowering Black women; and facilitating access to land, infrastructure, economic activities, ownership, as well as training and skills development (SA DTI 2004a:4-5). There are few studies that have effectively investigated the problems and benefits resulting from the attainment of specific BBBEE element objectives. Of these, none have yielded rich qualitative BEE data. The advertising industry has employed a multitude of innovative BBBEE ownership strategies in an attempt facilitate transformation and address a number of inherent problems. This has resulted in several success stories and benefits as the Cape Peninsula-based advertising agencies have embarked on their varied transformation journeys.

THE SA ADVERTISING INDUSTRY

Marketers spend huge sums of money, nearly R24.5 billion in 2008 (Koenderman 2009:42), on advertising to promote their products. The services of an advertising agency are typically employed to bring a more objective perspective to the marketer's company, and since they are specialists in this field, to provide the efficient creation, production and placement of marketing communication messages (Belch & Belch 2009:73-74). Only traditional full-service advertising agencies are included in the study. Traditional advertising agencies mainly utilise above-the-line (ATL) advertising (television, radio, newspaper, cinema, magazine and out-of-home) as opposed to below-the-line (BTL) promotions (sales promotions, point-of purchase, sponsorships and events) to reach the target market, whereas full-service agencies offers four key functions: creative services; media planning and buying; account management and planning; and production (Koekemoer 2004:110-113; 196-200).

Cape Peninsula advertising industry

The Western Cape is doing well in terms of the SA economy and makes the third largest contribution, although the advertising market is estimated to be about 20% the size of the Gauteng market (Koenderman 2008a:144). The Cape Peninsula advertising industry is still far from achieving its full potential (Paice 2004:18-20), largely as a result of intrinsic and unique problems:

• Charisse Tabak, MD of Nota Bene, feels that several Cape Peninsula-based agencies have empowerment deals, but the partners are rarely given an opportunity to make a worthwhile contribution to the business (Koenderman 2005:105-108). Conversely, Kevan Aspoas, MD of The Jupiter Drawing Room (TDJR), believes that BEE partners did not want to play an active role in the business (Manson 2005:102-105).

• Paice (2004:18-20) states that the SA government is a key commissioner of advertising work, but the fact that the Western Cape ruling party is different from the rest of the country, has resulted in the Cape Town being viewed as an unfriendly city for Black South Africans.

• Nicky Swartz, MD of TBWA Hunt Lascaris, believes that the greatest impediment of working in the Cape Peninsula is the progressively smaller amount of national marketing spend and feels that advertising agencies operate in a diminishing market (Paice 2006:110-112). Koenderman (2008a:144) agreed with these sentiments and explained that several Cape Peninsula-based agencies operated in a small and overcrowded environment.

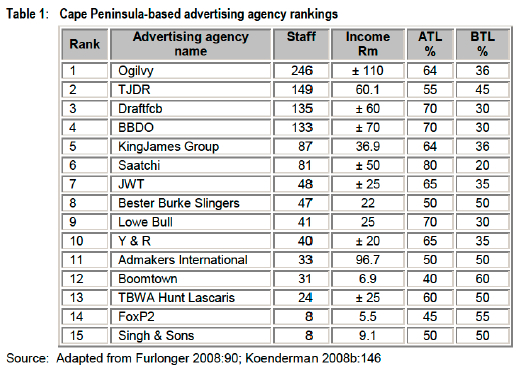

Paice (2006:110-112) affirms that Cape Peninsula-based agencies have been adversely influenced by changes in global marketing business, establishment of new agencies and an increase in specialist agencies. However, there has been an increase in ATL advertising spend owing to the strong economy, business confidence of clients and new entrants in the marketplace. Table 1 depicts the largest Cape Peninsula-based advertising agencies in terms of staff numbers, estimated income in Rand value and ATL and BTL percentages.

The twelve largest (in respect of income) full-service advertising agencies in the Cape Peninsula fall within the ambit of the study. Another delimitation of the study is that the advertising agencies must also be designated employers, in other words employ more than 50 employees or have an estimated income that exceeds R10 million for the transport, storage and communication (TSC) sector.

Important SA transformation advertising body

There are many SA advertising and associated industry organisations that are involved in an array of industry functions, but the most significant body is the Association for Communication and Advertising (ACA). This advertising body represents the collective interests of its member advertising agencies and is estimated to represent 80% of total advertising spend (ACA 2007). The ACA is the main instigator of transformation and has shown unwavering commitment to this cause, which includes the following highlights:

• The first ACA transformation charter was concluded in 2000. A self-imposed Black ownership target of 26% by 2009 was set (Clayton 2004). Advertising agencies would be barred from government business, as well as multinational and other private sector business, without a minimum of 26% of Black ownership (Koenderman 2002:66).

• The ACA gave its full co-operation to the SA government during the 2001 and 2002 parliamentary hearings that investigated accusations of racism in the advertising industry.

• ACA's commitment to proceed with transformation was confirmed by a draft scorecard in 2004 and two subsequent transformation charters in 2005 and 2007.

• Their endeavours to transform the industry reached a climax when the MAC transformation charter was gazetted on 29 August 2008 (Jones 2008). The MAC transformation charter set a BBBEE ownership target of 30% by 2009 and 45% by 2014 (SA 2008:7).

For almost a decade, the ACA has reflected the advertising industry's desire to transform. However, the government has not been swift in promulgating BEE legislation, which has an adverse effect on economic development (Swart 2006:48) and resulted in several changes to the abovementioned scorecards and charters.

OVERVIEW OF BEE

Transformation and BEE are often referred to interchangeably; however, transformation does not start and end with BEE, rather, it commences with the altering of attitudes and perceptions (Xate 2006:14). SA's first democratic government was elected in 1994 with a clear directive to transform the economic, political and social landscape, as well as remedy past disparities. This directive is enshrined in SA s Constitution, which embodies equality rights of all persons and provides instruments to address inequalities of the past (SA DTI 2004b:4-11).

Waves of BEE

BEE can be divided into three distinguishing periods that are described as "waves". BEE wave one started in 1993 and focussed on employment-related problems and legislation, such as the Employment Equity (EE) Act No. 55 of 1998 that aimed to eliminate unfair discrimination and implement AA measures (SA DoL 1998). The legislation that was passed in the first BEE wave has accomplished much in undoing the legacy of Apartheid. However, there were no guidelines for empowerment and BBBEE ownership. Transformation was predominantly driven by the private business sector, which resulted in only a small number of successful Black companies. BEE wave one ended in 1998, when the time was right for introduction of a detailed and more purposeful BEE strategy (Jack 2006:19-23).

BEE wave two commenced in 1999 and is characterised by the passing of initial BEE legislation: BEE strategy document, BBBEE Bill and the much anticipated BBBEE Act No. 53 of 2003 that placed renewed impetus on empowerment. The principle objectives of the BBBEE Act, which expressly pertain to BBBEE ownership, include:

• Attain a significant ownership, racial and management change in current and new organisations.

• Increase the number of Black women that own and manage in current and new organisations.

• Promoting investment programmes that lead to broad-based and meaningful participation in the economy by Black people (SA DTI 2004a:5-6).

The BBBEE Act also outlined provisos for the gazetting of transformation charters, so as to provide different industries with the opportunity to take intrinsic factors into account when implementing BEE measures (SA DTI 2005:4).

Stage one of BEE wave three began in 2004 when the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) was commissioned to develop the Codes on BBBEE, which were based on the provisos of the BBBEE Act. The primary purpose of the BBBEE Codes was to provide clear guidelines and principles to aid public and private sectors to implement the BBBEE Act's objectives 2005 (SA DTI 2004a). The drafting of the BBBEE Codes was undertaken in two phases, with the first phase commencing in April 2004, while the final draft of the second phase was submitted to cabinet for approval in December 2006 (Empowerdex 2007a).

Stage two of BEE wave three began when the BBBEE Codes of Good Practice was gazetted on 9 February 2007, which supplied the framework on how to commence and quantify (in the form of a generic or charter scorecard) BEE progress. Employing a few token previously disadvantaged individuals (PDIs) and securing a BEE affiliate would no longer achieve the conditions of BEE, since participation was now compulsory in all facets of the enterprise (Lalu & Webb 2007). There are seven BBBEE elements that include ownership, management, EE, skills development, preferential procurement, enterprise development and corporate social investment (SA DTI 2007:8).

BBBEE ownership element

This study only focuses on BBBEE ownership that measures the effective ownership of companies by Black individuals (SA DTI 2007:8). The first BEE deals in the late revealed a number of problems with BEE transactions:

• The low participation of Black women in BEE deals.

• The reversal of Black equity to White owners owing to a breakdown of BEE deals, as a result of complex structuring and burdensome repayment terms.

• The BEE ownership status of entities was exaggerated when compared to the actual financial benefits that Black beneficiaries received, as they were diminished by financing and voting limitations.

• The low level of participation by broad-based beneficiaries such as Black rural people, Black unemployed people, Black workers and Black disabled people (Black designated groups).

• Several deals were concluded amongst a few elite BEE individuals, as there was no inducement for entities to search further than these individuals.

• Fronting was problematic and is defined as any entity, mechanism or structure established in order to evade BEE requirements or to misrepresent BEE status.

The BBBEE Codes dealt with these issues by providing specific inducements in the BBBEE ownership scorecard to ensure participation by Black women, Black designated groups and Black new entrants, thus ensuring that only the economic interests of Black individuals was considered (SA DTI 2005:22).

Transformation charters

The BBBEE Codes provides a complete regulatory framework to direct the formation of transformation charters, which also allows for them to be gazetted, either in terms of Section 9 or 12. The charter targets are equivalent to BBBEE scorecards and become compulsory for all industry members if gazetted in terms of Section 9. However, the charter targets only serve as a guideline, and compliance with the BBBEE scorecard remains mandatory, if gazetted in terms of Section 12 (Empowerdex 2007b). The MAC transformation charter was gazetted in 2008 under Section 12 of the BBBEE Codes (Jones 2008). Consequently, advertising agencies are still required to comply with government legislation, but should also strive to achieve the charter objectives, since they will ultimately become binding once the charter is gazetted in terms of Section 9 of the BBBEE Codes. There are only two major differences between the MAC transformation charter and BBBEE Codes ownership scorecards. Firstly, the BBBEE Codes scorecard offers three bonus points, in addition to the twenty points on offer in both of the scorecards. Secondly, the compliance targets are higher in a shorter timeframe when comparing the MAC transformation ownership scorecard (45% by 2014) to the BBBEE Codes ownership scorecard (25% + 1 in 10 years) (SA 2008:13; SA DTI 2007:33).

Challenges of BEE

There are still many challenges pertaining to BEE implementation. Those that explicitly relate to BBBEE ownership include:

• Narrow-based BEE ownership - this practice tends to benefit very few Black investors (Burger 2009:16-21; Hoffman 2008:10-11; Janssens, Van Rooyen, Sefoko & Bostyn 2006:381-405; Naidu 2008:6; Petersen 2007:24-26). Piliso (2008:1) declared that in excess of R300 million worth of BEE deals had transpired since 1994, with the bulk benefiting a diminutive amount of elite Black investors, many of which were government affiliated. Conversely, several inventive BBBEE ownership offers provide shares in blue-chip companies (such as Barloworld, MTN, Multichoice, Nedbank, Sasol, and Telkom) to PDIs at reduced prices (Milazi 2008a:8; Milazi 2008b:15; Sutcliffe 2006/2007:26). However, the major problems with this innovative BBBEE ownership initiative is that the average PDI cannot afford the high price of big corporate shares and, secondly, the global financial crisis has resulted in devaluation of these BEE shares, which has created a short-term loss since they were issued (Milazi 2008c:15).

• Devious government relationships - some organisations deliberately establish relationships with government affiliates, so as to unjustly receive government business (Balshaw & Goldberg 2005; Naidu 2008:6; Turok 2006:59-64) that represents 40% of all expenditure in the SA (Piliso 2008:1). However, the Public Administration Management Bill intends to prevent civil servants from unfairly receiving government business (Mkhabela 2009:1-2).

• BEE investors make limited contributions to BEE agreements - a possible reason for this is that certain individuals enter into many ventures without the time or know-how to add value (BusinessMap Foundation 2004).

• Substantial BEE costs - the implementation of any individual BBBEE element is a costly exercise (in terms of money, time, commitment and other resources). Furthermore, companies are also frequently required to fund the investment risk of BEE deals to ensure that they succeed (IDC & ABC 2008:139-141; Turok 2006:59-64). Fauconnier and Mathur-Helm (2008:1-14) agreed with these sentiments and added that many BEE deals failed due to unsustainable funding schemes. Ackermann and Meyer (2007:23-44) found that banks viewed the lending of funds to BEE companies as a business risk. Although, others consider BEE to be an operation expense that will eventually result in lasting benefits (Burger 2009:16-21; BusinessMap Foundation 2004).

• Unfavourable for international investment - the abovementioned BEE outlay may dissuade foreign investment as a consequence of lower ROI (Butler 2006:80-85). The shortage management of expertise compounds Black owned companies from acquiring profitable international business (Horn 2007:490-503; Ackermann & Meyer 2007:23-44). However, Wolmarans and Sartorius (2009:180-193) states that BEE deal statements resulted in increased share prices. A Business Chamber study found that nearly 45% enterprises in Europe were optimistic about BEE, as opposed to 35% that felt BBBEE ownership was a hindrance (Hazelhurst 2006:14).

• Sandile Hlophe, director of KPMG, asserted that several companies had simply adopted the scorecard approach to meet the minimum stipulations of legislation. He felt that this would add no real value to BEE, but was merely fiddling with figures (Peacock 2007:16). He added that the selection of Black partners had been questionable from the start of BEE and that failure to deliver on transformation has led to the increased restlessness of the Black majority for faster implementation (Milazi 2008a:8).

Studies in other industries, such as the wine/agriculture (IDC & ABC 2008:139-141; Janssens et al 2006:381-405), engineering (Sherwood 2007:73-96), mining (Fauconnier & Mathur-Helm 2008:1-14), motorcar (Horn 2007:490-503) and tourism (Siyengo 2007:30-51), exposed similar BEE challenges. The advertising agencies also experienced some of the abovementioned problems, as well as also others that are intrinsic to the advertising industry and the Cape Peninsula. These are identified and discussed in the results of this study.

RECENT BEE SURVEYS

The abovementioned criticism directed at the failings of BEE has resulted in several national surveys that were tasked to quantitatively determine BEE progress across sectors in SA. Furthermore, the ACA also conduct annual surveys that measure various BBBEE elements' progress.

BBBEE baseline 2007 survey

The primary goals of the BBBEE baseline 2007 survey was to determine the progress and provide a benchmark for BEE. The TSC sector accounted for eight percent of the 1782 companies that took part in the survey. The BBBEE ownership element made the greatest progress, in that companies had attained 60.3% of the BBBEE scorecard target, however this has been largely negated by the fact that a handful of individuals or organisations have benefited from BEE ownership empowerment deals. It can be concluded from the survey that that organisations have begun the process, by implementing the BBBEE elements that provided the most direct benefits (such as BBBEE ownership), whereas the indirect strategy of empowerment was mostly disregarded (Consulta Research 2007).

KPMG BEE 2008 survey

KPMG also commissioned a survey to determine on BEE progress of five hundred companies, with the TSC sector accounting for 26% of the participants. The findings of the survey showed that BBBEE ownership had only achieved 42.5% the scorecard target. This adverse result could mainly be attributed to the more rigorous requirements of the BBBEE Codes that had been gazetted in the previous year, as well as the smaller sample size. However, the TSC sector's BBBEE ownership was measured at 62% of the target, which is in line with the results of the BBBEE baseline 2007 survey. Findings in terms of the BEE progress regression in many sectors do not bode well for significant equitable monetary opportunities for all South Africans, but at least some sectors (such as the TSC sector) have made significant headway (KPMG 2008).

ACA surveys

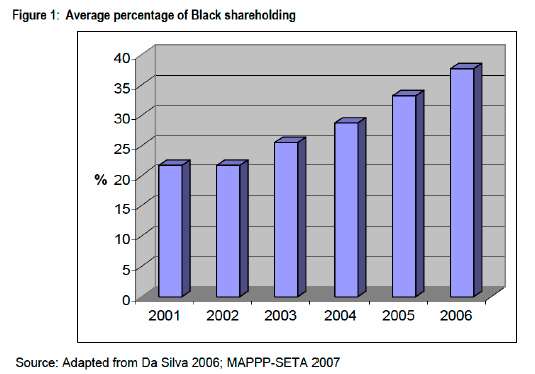

The ACA has quantitatively determined its members' BEE progress via the Employee Cost to Agency Survey that measures Black employee representation and the Empowerment Equity Survey that assesses Black shareholding. The results of the most recent survey in 2006 reveal that Black shareholding in the SA advertising industry increased from 21.7% in 2001 to 37.6% in 2006 (Da Silva 2006; MAPPP-SETA 2007). Refer to Figure 1 for the average percentage of Black shareholding over a six year period. The steady increase of shareholding reveals a positive trend in terms of Black ownership and gives the impression that the MAC transformation charter target of 45% BBBEE ownership (by 2014) should be accomplished.

Despite the strides made in transformation, with most frontline advertising agencies completing BEE deals over the past decade, over 70% of respondents in the AdFocus 2007 opinion survey of senior advertising executives stated that they still experienced transformation difficulties (Maggs 2007:109).

RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The ACA is the self-regulatory controlling body for SA advertising agencies and has been the major driving force of transformation within the industry. As mentioned in prior text, the ACA's initiatives to transform the industry, reached a climax when the MAC transformation charter was gazetted in 2008 under Section 12 of the BBBEE Codes (Jones 2008). Consequently, advertising agencies are still required to comply with government legislation, but also strive to achieve the charter objectives. Therefore, the principal objective of this study examines the challenges and benefits that Cape Peninsula-based advertising agencies encounter, whilst endeavouring to comply with the BBBEE Codes and MAC transformation charter ownership targets.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Paradigmatic perspective and research approach

The study adopts an interpretivist paradigm, which proposes that persons strive to achieve a detailed understanding of their surroundings (Miles & Huberman 1994:8) and making sense of their social situation (Ritchie & Lewis 2003:12). This study aims to make sense of the participants' worlds by interacting with them, understanding and clarifying meanings that they attribute to their experiences (Terre Blanche & Durrheim 1999:123-130) specifically pertaining to the challenges and benefits that result from the BBBEE ownership progress of each advertising agency. Qualitative research approaches usually employ a limited number of cases (Silverman 2005:9), but tend to strive for a deeper understanding rather than large sample sizes and vast amounts of data (Henning 2004:3). Consequently, this approach was used to accomplish the aforementioned research objectives.

Research design

The research design is the strategy that shifts from the underlying qualitative assumptions to the actual specifying of respondents, data collection techniques and analysis of data (Maree 2007:70). The case study design typically entails the examination of a single case (Welman, Kruger & Mitchell 2005:195), but in this study, the multiple case design was used to explore several cases. Twelve advertising agencies were analysed in terms of their BBBEE ownership activities that yielded more credible results in comparison to the single case design (Yin 2003:53).

Participants

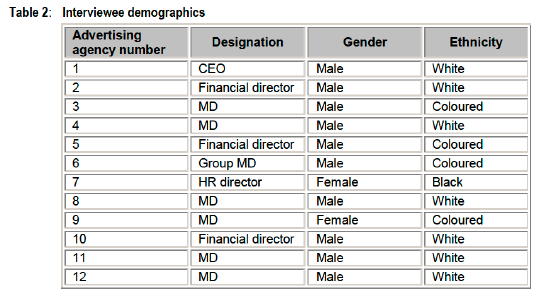

The research population consisted of the top twelve traditional full-service Cape Peninsula-based advertising agencies that were classified as designated employers. A senior employee (refer to Table 2 for the interviewee demographics), from each advertising agency, was targeted and all agreed to participate in the study. This resulted in a census, since the whole research population was included in the study (Welman et al 2005:101).

Data collection and analysis

The data was obtained from several sources, namely interviews and company documents, which provided both quantitative and qualitative data. Semi-structured interviews were used to cover a range of topics (Ritchie & Lewis 2003:110-111) and allowed the researcher to establish rapport with the participants, which resulted in a greater quantity of data (Maree 2007:294) and assisted with the acquisition of company documents (BEE contribution certificates) for triangulation purposes.

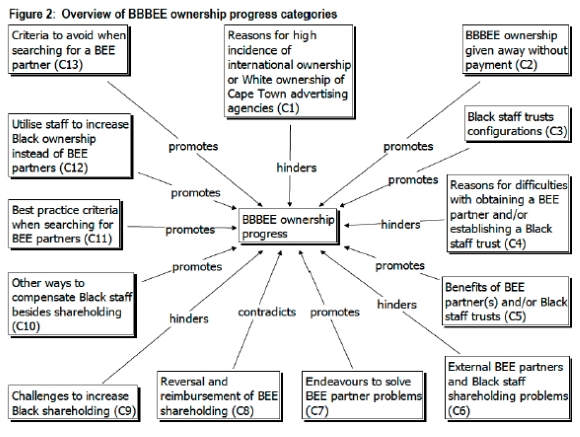

The content analysis approach (Mouton 2001:149-150) was used for the investigation of the data, which was a rational approach to examine the advertising agencies experiences and facilitated an analytical structure to organise the case studies (Yin 2003:114). A priori coding was utilised to determine the primary theme (BBBEE ownership progress), which yielded recurring patterns and divergent text that exposed thirteen categories (Marshall and Rossman 2006:158-159). A network illustration was generated by means of qualitative research software, Atlas.ti, so as to graphically depict the relationship between the theme and categories. The categories were analysed to obtain an understanding of the data and conclusions, which were compared to current literature in order to reveal important associations and divergences (Mouton 2001:124) discussed in the results of this study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The interviews and documents generated a mass of qualitative and quantitative data in terms of benefits and problems, as well as ownership structures and best practice. The results provide valuable insight into the extent to which advertising agencies have embraced and complied with BBBEE ownership in terms of DTI's scorecard and/or the MAC transformation charter's objectives. Refer to Figure 2 for an overview of the BBBEE ownership progress categories.

Figure 2 summarises and highlights the problems and benefits (including other factors) that promote, contradict and hinder BBBEE ownership progress in the Cape Peninsula advertising industry.

BBBEE ownership structures

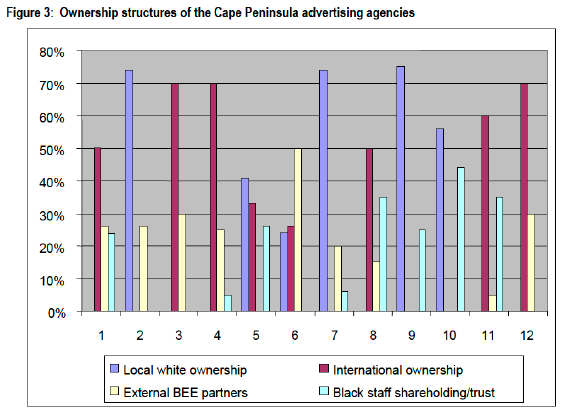

Three quarters of the Cape Peninsula's traditional full-service advertising agencies are either majority internationally-owned (five) or White-owned (four) versus a single majority Black-owned agency, one with precisely 50% Black shareholding and another with an equal spread of White, international and Black ownership. Refer to Figure 3 for a summary of the twelve advertising agency ownership structures.

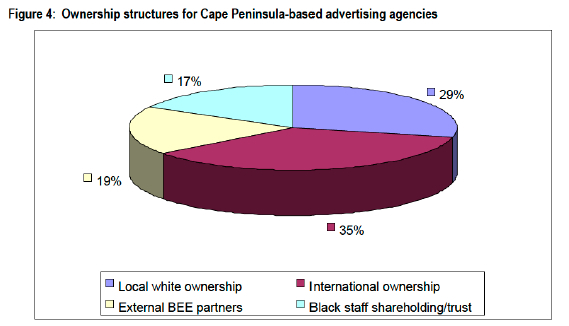

A combination of ownership structures were adopted by the advertising agencies in various ratios, but an encouraging finding was the incidence of an innovative Black ownership strategy, in the form of Black staff trusts that is discussed in Category 3. The researcher expected that the total Black ownership in the Cape Peninsula advertising industry would be higher than 36%, since several years have passed when the ACA reported the national average (2006) to be at 37.6% (Da Silva 2006). Refer to Figure 4 for an overview of the collective ownership structures of Cape Peninsula-based advertising agencies. Possible reasons for this low figure are discussed in Category 1. However, it is positive that a majority of agencies have already achieved the Black ownership MAC transformation charter target of 30% by 2009.

Category 1 - Reasons for high incidence of international ownership or White ownership of Cape Peninsula advertising agencies

International advertising agency groups can only use SA advertising agency figures in their consolidated financial statements if they own a majority stake. Furthermore, these advertising conglomerates can also only get their ROI out of SA by declaring dividends and can, consequently, determine the amount if they own a majority stake of the company. The principle reason for White owners having declined to give up their majority shareholding is that they were the founders of the advertising agencies, therefore, have worked long hours to build-up the advertising agency whilst enduring a tough economic climate, and now want to enjoy the fruits of their labour.

Category 2 - BBBEE ownership given away without payment

The fact that two advertising agencies gifted significant portions of their advertising agencies to advance BEE, are examples that portray real transformation, especially since both of these agencies are multimillion Rand operations. One advertising agency gave 25% of their company to an external BEE partner for free, since the shares were paid for via dividends, while and the other granted 20% of their shareholding to a Black staff trust at no cost.

Category 3 - Black staff trusts configurations

The allocation of shares to Black staff, usually a few senior members, can be described as Black staff shareholding. Whereas shares that are allocated to a trust, which is used to monetarily motivate and improve the lives of the larger proportion of Black advertising agency staff (that do not actually own the shares, but receive the benefits as long as they are employed by the agency), can be defined as a Black staff trust. Several advertising agencies reported to have Black staff trusts, although there was only one that could be classified as authentic trust in terms of the above definitions. This trust not only monetarily benefited all Black staff that were employed by the advertising agency, but also provided free training to develop their skills; and at the same time it did not totally exclude White staff that could benefit for monetary rewards via outstanding performance. Other aspects of Black staff trusts are investigated in Categories 4, 5 and 6.

Category 4 - Reasons for difficulties with obtaining a BEE partner and/or establishing a Black staff trust

A majority of the advertising agencies believe that it was a complex process to find a suitable BEE partner and/or to establish a Black staff trust. Advertising agencies did not necessarily have a problem in finding a BEE partner, but found it difficult to find the right one. The same problem was evident in mining industry and Fauconnier (2007:154-158) found that the following was important when evaluating possible BEE partners: knowledge of and dedication to the industry; BEE credentials; alignment of interests; full trust; and a strategic alignment with company values. Advertising agencies had similar requirements, but additionally wanted BEE partners to play a more active role in running the business.

Several advertising agencies experienced problems with their trusts either owing to a high trustee turnover or the fact that the international advertising conglomerate was not willing relinquish shareholding (refer to Category 1). There were also complexities in determining the finer details of exactly how the trust would work in order to be as non-discriminatory as possible. It is a complicated process to establish a Black staff trust, but the benefits (discussed in Category 5) ultimately outweigh the problems.

Category 5 - Benefits of BEE partner(s) and/or Black staff trusts

Advertising agencies are able to get onto pitch lists, since having a BEE partner would increase the BBBEE ownership element score, which would increase their BEE credentials. Others felt that new business, client retention, recruitment of Black PDIs, economies of scale, increased value of shares and staff expertise, were all additional benefits that were received from BEE partners. Refer to Categories 11 and 13 that provide information to validate the "new business" benefits.

A single advertising agency felt that Black staff trusts motivated staff to put more effort into their work and/or work more accurately. They had implemented an innovative staff trust where top performing Black staff stood a chance to get onto a board, whereby they would receive lucrative financial rewards, as well as additional training and mentoring. Maharaj, Ortlepp and Stacey (2008:27) found that senior Black employees' had raised expectations regarding training opportunities and financial rewards, which if not fulfilled, would increase the likelihood of them seeking alternative employment.

Category 6 - External BEE partners and Black staff shareholding problems

Problems from BEE partners included the following: terminating the deal to go to larger companies (this is a costly exercise); do not understand and/or alter perceptions of their role regarding operational issues; seeking fast short-term rewards and adding little value; inexperienced shareholders wasting time on trivial matters; and displaying little understanding of the advertising industry, but demand much in spite of doing nothing for the big dividends that they received. The BBBEE Codes took some of these problems into consideration when designing the BBBEE ownership scorecard element (SA DTI 2005:22), but the final version has only been in effect for a short period (less than three years), so whether it will help to solve these problems is yet to be seen.

Category 7 - Endeavours to solve BEE partner problems

There are no simple solutions to these problems, but a few advertising agencies have implemented innovative strategies in an effort to overcome them. Strategies such as giving the BEE partner office space or going away with them to help understand one another, were attempted. The first strategy failed, whereas as the second strategy resulted in a positive outcome. Burger (2009:21) believes that it takes serious commitment and a large contribution of abilities to empower BEE partners, and in order to improve their capabilities.

Category 8 - Reversal and reimbursement of BEE shareholding

One advertising agency surprisingly implied that they would decrease their Black shareholding in order to give it back to White managers that sacrificed it for the sake of BEE progress. This unusual phenomenon reveals what some surrendered to in order to advance transformation.

Category 9 - Challenges to increase Black shareholding

A primary reason for the difficulty in increasing Black shareholders' percentage was a result of international ownership constraints. Other problems were alluded to when individuals needed to sacrifice a portion of their shareholding (which has financial implications) for the sake of BEE (refer to Category 8 as an example), as well as the actuality that it was difficult to give up something that one spent one's life building, especially if it has not reached its full potential.

Category 10- Other ways to compensate Black staff besides shareholding

Advertising agencies advocate that alternatives should be sought besides giving away shares to Black PDIs, such as investigating mechanisms of utilising other BBBEE elements or by means of different financial reward systems to compensate people. It has become clear that Black shareholding can only be increased by a certain extent, before more innovative alternatives should be sought to advance BEE, such as Black staff trusts that have already achieved a good measure of success.

Category 11 - Best practice criteria when searching for BEE partners

A majority of advertising agencies felt that best practice criteria, when seeking BEE partners, were to find those that were passionate, interested, understood, add value to the advertising agency and were able to work with them in running the business; but most added that this type of BEE partner was difficult to find. Advertising agencies also believed that increasing Black ownership was a long-term strategy and aspects of the deal should be carefully scrutinised so that all parties were content with parameters and potential benefits that were derived from the BEE agreement.

Category 12- Utilise staff to increase Black ownership instead of BEE partners

Some advertising agencies confirmed that Black staff shareholding/trusts were more effective than BEE partners, since staff tended to be more motivated to work harder if they owned a piece of the business. Black staff shareholding/trusts would help avoid the BEE partner problems that were identified in Category 5.

Category 13- Criteria to avoid when searching for a BEE partner

Some advertising agencies felt that it was easier to discuss what they were "not" looking for in BEE partners. They emphasised that investors did not make good BEE partners and insinuated that this was window dressing or fronting. One advertising agency condemned the practice of winning new business accounts merely because of who the BEE partner was, whereas others advocated that this should be a criterion and deliberately found BEE partners with great influence. Half of the advertising agencies had set stringent criteria, this as opposed to what happened in the past when silent BEE partners were found simply to increase Black ownership so as to achieve targets, which ultimately benefiting very few PDIs.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Several advertising agencies have made progress in terms of the BBBEE scorecard and/or MAC transformation charter goals by taking heed of past failures and developing unique strategies to overcome various ownership-related problems; these have lead to some distinctive benefits. The recommendations serve as a guide for the advertising, government and other industries.

Innovative BBBEE ownership structures

Black staff shareholding and/or trusts were created by 75% of advertising agencies and are predominantly broad-based. These do and will continue to benefit a great number of previously disadvantaged Black people. A greater number of advertising agencies should investigate the possibility of establishing Black staff trusts that will benefit all of their Black staff and other PDI stakeholders.

Difficulties in obtaining BEE partners and/or establishing Black staff trusts

A majority of advertising agencies felt that it was a difficult process to find a BEE partner that would promote real transformation and/or to establish Black staff trusts, which are lengthy, time-consuming and complicated concerns to initiate. Advertising agencies and other companies should be able to learn from difficulties that were encountered in establishing Black staff trusts and it is, therefore, suggested that the complications and successful trust configurations are publicised.

Good BEE credentials analogous with BEE partners/Black staff trusts benefits

The most common benefits include: getting on to pitch lists; new business; client retention; recruitment of new staff; economies of scale; appreciation of share worth; and improved staff proficiency. Black staff trusts' main benefit was to inspire staff to put more effort into their work in order to increase their chances of receiving rewards. The main benefits of Black staff trusts should be made public to inspire other advertising agencies to implement these advantageous Black ownership schemes.

External BEE partner problems

A number of potential problematic issues were raised such as: BEE partners leaving; suddenly changing the role they play in the advertising agency; conflict of interests (short-term goals versus long-term sustainability); adding little value; inexperience; not understanding the advertising business or earning their keep; and it being a long and costly process when they leave. There are no easy solutions to these problems, other than a thorough selection process. Several strategies have been implemented, although only with limited success, but at least advertising agencies are striving to find solutions. The strategy that worked well was when the BEE partners and entire senior management of an advertising agency went on a breakaway in an effort to understand each other and to resolve differences.

Uncertainty regarding intention to increase Black shareholding

A minority of advertising agencies expressed their intention to increase Black shareholding. A single advertising agency implied that they would be reversing some Black shareholding to compensate White management who had sacrificed their shares in order to promote BEE transformation. Other advertising agencies and government should also consider that real transformation is a not one-sided affair and implement strategies, at an appropriate time, to reimburse those who had made sacrifices to advance transformation.

Challenges to increase ownership percentage of Black shareholders

The main challenges to increase Black shareholding include international ownership constraints and the fact that individuals were required to sacrifice shareholding for the sake of BEE. Advertising agencies have begun to investigate other ways to reward Black staff besides shareholding, such as by examining other BBBEE elements or alternative monetary incentive schemes, for example, those mentioned in the form of Black staff trusts. Successful financial reward systems should also be made public so that other advertising agencies and companies could implement and benefit from them.

Best practice criteria when seeking BEE partners

The major best practice criteria for selecting BEE partners is to find those who are passionate, interesting, understanding and could add value to the advertising business by working or assisting with the running of the advertising agency. The aforementioned criteria should be considered by other companies and industries when selecting potential BEE partners.

The results of this study show that some Cape Peninsula-based advertising agencies have made BBBEE ownership progress so as to comply with the BBBEE and MAC ownership targets, but that there are still many problems. However, the implementation of innovative BBBEE ownership structures and strategies has resulted in added benefits and several success stories. The advertising industry commitment to ensure that transformation succeeds can be aptly summed up by one advertising agency's endeavour to solve their BEE partner problems: "We had a difficult period and both parties went into a 'bosberaad' and it was very good. Coming out of it was not completely solved, but it was a bit of a truth and reconciliation exercise. We both learnt and both came into the thing with very fixed ideas, and no-one's ever said this, but we left with giving a bit and found a bit of common ground."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACA. 2007. Member Agencies. [Internet: www.acasa.co.za; downloaded on 2008-10-01. [ Links ]]

ACKERMANN P.L.S. & MEYER P.G. 2007. The identification of credit risk mitigation factors in lending to Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) companies in South Africa. Southern African Business Review, 11(1):23-44. [ Links ]

BALSHAW T. & GOLDBERG J. 2005. Cracking broad-based Black economic empowerment, codes and scorecard unpacked. Cape Town: Human and Rosseau. [ Links ]

BELCH G.E. & BELCH M.A. 2009. Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communication Perspective. 8th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

BURGER L. 2009. BEE is big business: main feature. The Dairy Mail, 16(3):16-21. [ Links ]

BUSINESSMAP FOUNDATION. 2004. Empowerment 2004. Black ownership: risk or opportunity. [Internet: www.businessmap.org.za; downloaded on 2008-11-29. [ Links ]]

BUTLER A. 2006. Black economic empowerment: an overview. New Agenda, second quarter:80-85. [ Links ]

CLAYTON L. 2004. Presentation by the ACA chairperson at the parliamentary report-back on the transformation of the marketing and advertising industry. [E-mail: lia@aaaltd.co.za; received on 2004-10-29. [ Links ]]

CONSULTA RESEARCH. 2007. BBBEE Progress Baseline Report 2007. [Internet: www.dti.gov.za/bee/BaselineReport.htm; downloaded on 2008-11-05. [ Links ]]

COULSEN M. 2004. Economics 1996: Tale of two empowerments. Financial Mail: A decade of democracy, May 7:19-20. [ Links ]

DA SILVA I. 2006. ACA survey shows increased Black ownership. [Internet: www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/12/12606.html; downloaded on 2007-11-04. [ Links ]]

EMPOWERDEX. 2007a. Codes Process. [Internet: www.empowerdex.co.za/content/Default.aspx?ID=24; downloaded on 2008-10-11. [ Links ]]

EMPOWERDEX. 2007b. Codes or Charters? [Internet: http://www.empowerdex.co.za/content/Default.aspx?ID=21; downloaded on 2008-10-11. [ Links ]]

FAUCONNIER A. 2007. Black Economic Empowerment in the South African mining industry: a case study of Exxaro Limited. Unpublished Master of Business Administration thesis. University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

FAUCONNIER A. & MATHUR-HELM B. 2008. Black economic empowerment in the South African mining industry: a case study of Exxaro Limited. South African Journal of Business Management, 39(4):1-14. [ Links ]

FURLONGER D. 2008. Advertising agency performance. Financial Mail: AdFocus, November 28:90. [ Links ]

HAZELHURST E. 2006. Few European Firms in SA see benefits in BEE. Business Times, November 30:14. [ Links ]

HENNING E. 2004. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

HOFFMAN P. 2008. BEE vs equality: people risk. Enterprise Risk, 2(4):10-11. [ Links ]

HORN G.S. 2007 Black economic empowerment (BEE) in the Eastern Cape automotive industry: challenges and policies. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 10(4):490-503. [ Links ]

IDC & ABC. 2008. BEE shortfalls identified. The Dairy Mail, 15(2):139-141. [ Links ]

JACK V. 2006. Unpacking the different waves of BEE. New Agenda. South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy, 22:19-23. [ Links ]

JANSSENS W., VAN ROOYEN J., SEFOKO N. & BOSTYN F. 2006. Measuring perceived black economic empowerment in the South African wine industry. Agrekon, 45(4):381-405. [ Links ]

JONES G. 2008. MAC Transformation Charter gazetted. [Internet: www.marketingeb.co.za/marketingweb/view/marketingweb/en/page74600?oid=111182&sn=Marketingweb%20detail; downloaded on 2008-09-10. [ Links ]]

KOEKEMOER L. 2004. Marketing Communications. 1st Edition. Lansdowne: Juta. [ Links ]

KOENDERMAN T. 2002. Empowerment rush is on. Financial Mail. April 12:66. [ Links ]

KOENDERMAN T. 2005. Transforming Cape Town. Finance Week: AdReview. April 9:105-108. [ Links ]

KOENDERMAN T. 2008a. Creativity flowering in the fairest Cape. FIN Week: AdReview, May 1:144. [ Links ]

KOENDERMAN T. 2008b. Leading Cape agencies, FIN Week: AdReview. May 1:146. [ Links ]

KOENDERMAN T. 2009. Adspend by medium 2008. FIN Week: AdReview, April 20:42. [ Links ]

KPMG. 2008. BEE Survey 2008. [Internet: www.kpmg.co.za/images/naledi/pdf%20documents/remote/kpmg%20bee%202008%20survey.pdf; downloaded on 2008-09-11. [ Links ]]

LALU A. & WEBB K. 2007. Gazetting the final Codes of Good Practice. [Internet: www.bee.sabinet.co.za; downloaded on 2008-11-07. [ Links ]]

MAGGS J. 2007. What senior agency executives think? Financial Mail: AdFocus, May 25:109. [ Links ]

MAHARAJ K, ORTLEPP K & STACEY A. 2008. Psychological contracts and employment equity practices: A comparative study. Management Dynamics, 17(1):27. [ Links ]

MANSON H. 2005. Transforming Cape Town. Finance Week: AdReview, April 9:102-105. [ Links ]

MAPPP-SETA. 2007. Advertising skills needs analysis research report. www.mapppseta.co.za/formsadvskills.pdf. [Internet: www.bee.sabinet.co.za; downloaded on 2008-12-04. [ Links ]]

MAREE K. 2007. First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

MARSHALL C. & ROSSMAN G.B. 2006. Designing qualitative research. 4th edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

MILAZI M. 2008a. Self-defeating attitudes. Business Times: Trailblazers, September 28:8. [ Links ]

MILAZI M. 2008b. Cheap shares are a step in the right direction. Business Times, July 13:15 [ Links ]

MILAZI M. 2008c. Markets wipe out BEE gains. Business Times, October 12:15. [ Links ]

MILES M.B. & HUBERMAN A.M. 1994. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

MKHABELA M. 2009. New law to stop the gravy train. Sunday Times, August 9:1-2. [ Links ]

MOUTON J. 2001. How to succeed in your master's and doctoral studies: a South African guide and resource book. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

NAIDU B. 2008. Empowerment in the spotlight. Business Times, October 19:6. [ Links ]

PAICE D. 2004. While you were sleeping. Marketing Mix, 11(6):18-20. [ Links ]

PAICE D. 2006. A fine 2006 vintage. FIN Week: AdReview. April 27:110-112. [ Links ]

PEACOCK B. 2007. Transformation: no place to hide. Business Times, May 20:16. [ Links ]

PETERSEN E. 2007. Those Codes raise concerns about narrow-based BEE: BEE law. Without Prejudice, 7(6):24-26. [ Links ]

PILISO S. 2008. Gravy train on track. Business Times, July 13:1. [ Links ]

RITCHIE J. & LEWIS J. 2003. Qualitative research practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

SHERWOOD C.J. 2007. The effect and consequences of Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment on South African engineering. Unpublished Master of Business Administration thesis. Oxford Brookes University, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

SILVERMAN D. 2005. Doing qualitative research. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

SIYENGO S. 2007. Black Economic Empowerment challenges within the Western Cape tourism industry. Unpublished Master of Business Administration thesis. University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

SA. 2008. Media, Advertising and Communication (MAC) sector charter on BEE. Notice in terms of section 12 of the BBBEE Act, 2003 (Act No. 53 of 2003). Government Gazette, 924(31371):3-31. [ Links ]

SA. [DoL]. 1998. Employment Equity Act (Act No. 55 of 1998). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SA. [DTI]. 2004a. Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act (Act No. 53 of 2003). Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SA. [DTI]. 2004b. South Africa's Economic Transformation: A Strategy for Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SA. [DTI]. 2005. The Codes of Good Practice: Phase one: A guide to interpreting the first phase of the codes. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SA. [DTI]. 2007. Codes of Good Practice for Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment - BBBEE Booklet. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

SUTCLIFFE J. 2006/2007. Black Economic Empowerment: empowerment in SA paying healthy dividends. Human Capital Management, 4:26. [ Links ]

SWART L. 2006. Affirmative action and BEE: are they unique to South Africa? Management Today, 22(4):48. [ Links ]

TERRE BLANCHE M. & DURRHEIM K. 1999. Research in practice for social sciences. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

TUROK B. 2006. BEE transactions and their unintended consequences. New Agenda. South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy, 22:59-64. [ Links ]

WELMAN C., KRUGER F. & MITCHELL B. 2005. Research Methodology. 3rd edition. Cape Town: Oxford. [ Links ]

WOLMARANS H. & SARTORIUS K. 2009. Corporate social responsibility: the financial impact of Black Economic Empowerment transactions in South Africa. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 12(2):180-193. [ Links ]

XATE N. 2006. The word game. Financial Mail: AdFocus, May 12:14. [ Links ]

YIN R.K. 2003. Case study research. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]