Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.7 no.1 Meyerton 2010

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Use of barter trade in the South African media industry

P Oliver; M Mpinganjira

Department of Marketing Management, University of Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

Barter trade is often associated with high levels of inefficiencies when compared to modern monetary transactions. Despite this, there has been a reported resurgence of this trade worldwide since the 1990's. This resurgence has however not been matched with research interest in the field. This paper aims at empirically investigating the use of barter trade in the South African media industry. Data was collected from a sample of 70 media organisations. A structured questionnaire looking at a number of issues relating to barter trade including current use; past practices and future prospects regarding use; products commonly accepted and perceived benefits was used to collect the data. The results show that use of barter trade is a very common practice in the South African media industry and many firms in the industry plan on continuing to engage in the practice. A wide range of products are commonly accepted in barter deals including advertising/media space, travel and hospitality services as well as various types of fixed assets. The findings show that both barter practitioners and non-practitioners perceive a lot of benefits associated with barter trade. The high barter trade prevalence in the media industry offers opportunities for firms to better manage their promotional efforts without incurring huge cash outlays.

Key phrases: Barter trade, media Industry, South Africa, countertrade

INTRODUCTION

Barter trade, considered the world's oldest form of exchange, is often associated with mixed views in modern business circles. On one end of the spectrum are those who consider barter as an archaic form of trade characterised by gross inefficiencies with little or no room for it in the modern business environment. On the other hand are those who view barter trade as a progressive strategic business tool, with definitive financial and marketing benefits. Researchers who have explored a middle ground between the extreme views have often come to the conclusion that this form of trade can be beneficial under some circumstances mostly to do with difficult economic or business times (Crest 2005:1955; Lecraw 1989:41). Campbell (2009:1) noted that companies typically begin using barter trade when they have excess or underperforming assets.

Although money is generally considered a more efficient medium of exchange for business transactions, there has been a resurgence of barter trade since the 1990's (Small Business Association 2008:1; Cresti 2005:1953). According to the Universal Barter Group (2008:1) the 2004 barter industry statistics showed that barter accounts for 30 percent of the world's total business and 65% of corporations listed on the NYSE are involved in bartering. They also noted that almost one-third of small businesses in the US use some form of bartering. Although up-date statistics on barter trade are difficult to get, indications are that the practice is growing each year (Small Business Association 2008:1)

Stubin (2004:1) as well as Barr (1993:31) noted that a majority of barter deals in America involve some form of media usually advertising time or space. This is said to be so due to the perishable nature of advertising time or media space. An advertising time slot is worth absolutely nothing once the time has gone past.

PROBLEM STATEMENT AND RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

Despite its growing popularity barter trade in general and domestic barter trade in particular has not managed to attract much research attention in both developed and developing nations. Except for a few empirical studies on the subject many of which were conducted in the late 1980's and early 1990's, most of what is written on the subject is based on anecdotal evidence. This paper aims at contributing to bridging this gap by empirically investigating the use of barter trade in the South African media industry. The specific objectives of this paper are (1) to find out how widely practiced barter trade is in the South African media industry (2) identify the products commonly accepted in barter trade and (3) investigate the perceived benefits associated with barter trade.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Barter, often defined as trading goods and/or services for other goods and/or services, is considered the world's oldest form of exchange (Orme 2004:70). Hennart (1990:243) noted that barter trade has changed over the years with newer forms, known as 'countertrade', characterised by variations of conditions and agreements. Countertrade can thus be viewed as a form of bartering that includes and goes beyond the pure exchange of commodities. Typical forms of countertrade include simple/pure barter; buybacks, counter purchase, and offsets (London Countertrade Roundtable 2007:1; Hennart 1990:244). Lecraw (1989:43) defined simple/pure barter as the one time, direct exchange of goods/services between two or more trading partners without the exchange of money. Hennart (1990:244) noted that unlike simple barter, all other forms of countertrade consists of more than one contact. Buybacks and counter-purchase are closely related in that buyback is a form of barter where the suppliers of plant or equipment agree to be paid in full or part with a share of the output produced by these goods while in the case of counter-purchase the goods that are taken back are not produced with the equipment sold (Hennart 1990:244; Lecraw 1989:43).

Hennart (1990:246) noted that 'offsets' is a term used to describe the imposition on sellers of a more complex basket of reciprocal concessions. The London Countertrade Roundtable (2007:1) noted that offsets are common with large international contracts often involving government where due to the large size of the contract the government insists that the seller offsets the price in some other way usually through such means as the establishment of local production and/or transfer of technology.

The focus of this paper is on barter in general. The term is used in a generic sense to mean any form or variant of trade in which full or partial payment for goods and/or services is made using other goods and/or services. The definition adopted is in line with how others have defined barter in literature. For example in their empirical research on use of barter trade in the broadcasting industry in the US Kassaye and Vaccaro (1993:40) defined barter as a form of transaction that requires the seller to make a contractual obligation to the buyer to accept full or partial payment in goods and/or services.

There are many reasons why firms may chose to trade using barter. According to Stout (2007:1) barter can help increase a company's sales volume by among other ways attracting customers who would ordinarily not be able to afford the company's goods or services. He further noted that in many organisations needs for products and services is not always matched with ability to pay. Allowing customers pay for goods and/or services using goods and/or services they have can thus help ensure that a sale takes place. McCammon (2006:1) described cash savings as a primary motivator for using barter trade. According to Mardak (2002:45) barter trade is a secondary market that is used when companies are having difficulties in selling their goods/services in their primary markets. He further noted that this secondary market is represented by an entirely different market of potential buyers. Barter trade can thus help organisations access new markets. Healey (1989:118) noted that use of barter brokers in barter trade can also help organisations access new markets. This is due to the fact that brokers have access to a range of potential customers outside a company's scope of its normal business operations.

As barter trade often involves protracted negotiations, this gives opportunity for a seller to get closer to the customer. Ference (2009:1) noted that businesses that regularly barter with each other build long-term relationships based on trust. This relationship may well extend into future cash-based transactions. Egan and Shipley (1996:112) noted that when a company allows its normal cash paying customers to make payment using goods/services in their time of cash problems, it can help in building good image for the company in that it will be seen as a caring company that identifies with the needs of its customers. One other benefit of barter trade is thus that it can help a company better manage its cash flow.

According to Healey (1989:117) the common feature of companies that are drawn into barter is that all have goods which they cannot easily, or profitably sell for cash through conventional channels. Campbell (2009:2) noted that the payment received for such inventory using barter trade would normally exceed its fair value based on the understanding that the seller company will now spend the same value on the buying company's goods/services. Healey (1989:117) noted that instead of selling 'distressed products' to usual retailers at a very substantial discount, barter trade allows companies to manage their excess inventory profitably. He further noted that selling 'distressed inventory at substantial discount to usual retailers might also damage a company's long-term market position as it may be seen as publicly admitting their commercial weakness.

Liesch and Palia (1999:503) as well as Barr (1993:32) noted that barter is used by companies as a creative tool for keeping production lines busy and to achieve economies of scale through capacity maximisation. It is also often argued that lack of transparency often associated with barter markets makes it a vehicle for disguising price discounts to avoid 'price wars' among competitors (Healey 1996:37). It allows discounting without antagonising traditional customers who continue to buy at normal prices. Additionally, it can help in bypassing creditor monitoring and avoiding taxes (Cellarius 2000:75; Hennart 1990:250).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The data used in the analysis was collected from three main media sectors in South Africa namely the broadcasting, print and the outdoor media. A sample frame was developed using listings of media organisations obtained from the South African Government Communication and Information Systems (GCIS) Media Contact Directory, the Magazine Publishers Association of South Africa (MPASA); and the Out of Home Media South Africa (OHMSA) members. It consisted of a total of 197 media organisations all of which shared a common interest in that they offer a medium of mass communication to the South African public. The media organisations were identified at the business unit level despite the fact that most media organisations in South Africa are in the hands of a few companied at the corporate level. This was mainly because of two main reasons which included the fact that the media listings used to come up with the sample frame were at business unit level and also the realisation that business management practices often vary even between entities under the same corporate umbrella. A stratified sample of 120 media organisations was drawn from the sample frame. The organisations were stratified according to sectors/sub-sectors in the media industry namely television and radio in the broadcasting sector; newspapers and magazines in the print sector and the outdoor sector.

A structured questionnaire was the main instrument used to collect the data. The first draft of the questionnaire was developed after a review of literature on the topic and some in-depth interviews with a convenience sample of five executives from the media industry knowledgeable in barter trade issues. It was then pre-tested on a convenience sample of 15 respondents from the media industry before coming up with the final version. The main purpose of the pre-testing was to check if the questions were easily understood by the respondents and solicit their suggestions for modifications and additional questions relating barter issues being investigated. The questionnaire investigated a number of issues relating to barter trade including use of barter trade, past practices and future prospects regarding use of barter trade, products commonly accepted in barter trade with the most common ones ranked first and benefits associated with barter trade. A five point Likert scale with 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree, was used to measure the extent to which respondents regarded a number of factors as benefits of barter trade.

The final questionnaire was electronically mailed as an attachment to contact personnel in each of the organisation in the sample. The e-mail had the subject heading "Barter Trade in the Media Industry in South Africa Survey Questionnaire'. The body of the e-mail gave a short introduction of the survey and a request asking the contact person to pass on the questionnaire to the senior person that deals with barter trade in the organisation or to the head of marketing. This was often followed up with telephone calls to ensure that the questionnaire had been received and passed on to the right person. Contact details of the individual respondents were solicited for the purposes of making follow-ups.

A total of 70 usable responses representing 58 percent response rate was obtained. The personnel that responded to the questionnaire on behalf of their organisations were mostly in management positions with 24 indicating that they were marketing managers; 21 indicated that they were part of executive management i.e. chief executive officers, executive directors, and owners; 22 indicated that they were in other senior management positions while 3 were barter specialists.

The data obtained was statistically analysed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 15.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

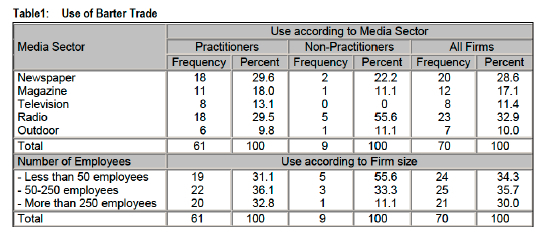

Table 1 presents results on use of barter trade. Apart from looking at usage among all the firms the results also present findings on usage in firms from different media categories and firms of different sizes. According to the results out of the 70 firms involved in the study, 61 indicated that they were currently involved in barter trade. This represents 87.1 percent of the respondents. Only 9 firms representing 12.9 percent of the respondents were not currently involved in barter trade.

An analysis of use by media sector shows that 8 firms in the television sector, representing 100 percent of the respondents in that category were involved in barter trade. 11 out 12 firms in the magazine sector and 18 out of 20 in the newspaper sector representing 92 and 90 percent of the respondents respectively indicated using barter trade. Out of the 7 firms in the outdoor sector only 1 indicated not using barter trade representing a usage rate of 86 percent. The lowest usage rate was at 78 percent and this was in the radio sector where 18 out of the 23 firms indicated practising barter trade.

Out of the 70 firms involved in the study, 24 had less than 50 employees, 25 had between 50 and 250 employees while 21 had more than 250 employees. Results on an investigation of barter usage among firms of different sizes shows that 19 out of the 24 firms with less than 50 employees were involved in barter trade. This represents 79 percent usage rate among firms in this category. 22 out of 25 and 20 out of 21 firms with 50 to 250 employees and more than 250 employees respectively indicated that they were involved in barter trade. This represents 88 and 95 percent respectively of the firms in each of the two categories.

From the results on usage it is clear that use of barter trade is a very common practice in the South African media industry. Its usage cuts across all the major mass media sectors and is popular among all firms irrespective of firm size. The high prevalence of barter practice in the South African media industry is consistent with findings in the US. As noted before, Stubin (2004:1), as well as Barr (1993:31), noted that in the US barter trade is highly prevalent in the media industry.

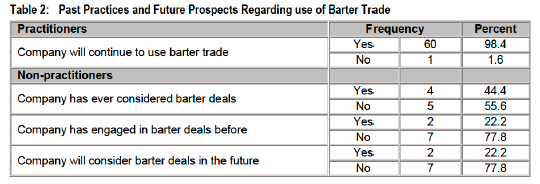

Table 2 presents findings on past practices and future prospects of the firms in relation to use of barter trade. According to the results 60 of the 61 barter practitioners representing 98.4 percent indicated that they will continue to use barter trade. This shows that the practitioners see value in barter trade, otherwise such as big majority would not be willing to continue with the practice.

On the part of non-practitioners, 4 representing 44.4 percent indicated that they had considered barter trade in the past but only 2 representing 22.2 percent indicated that they will consider barter deals in the future. Out of the four firms that indicated to have considered barter trade in the past two indicated that they had engaged in the practice.

The findings also show that barter trade is not a temporary phenomenon but a practice that will continue to be practiced in the industry. This is evident especially from the fact that 98.4 percent of the current practitioners indicated that their companies will continue to engage in barter trade in the future while 22.2 percent of the non-practitioners were certain that they will consider barter deals in the future.

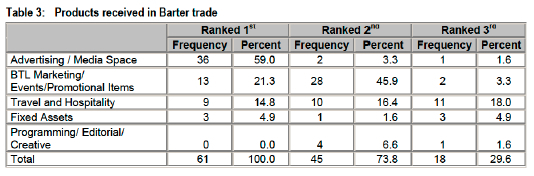

Each barter practicing firm was asked to indicate the products commonly accepted in its barter deals with the most common ones indicated first. The findings showed that a wide range of products are commonly accepted and these were grouped into five categories namely advertising/media space; below the line marketing (BTL) which included branding and sponsorship opportunities, hosting of events, promotional clothing and other items; programming, editorial, creative work; travel and hospitality; and fixed assets. Table 3 presents a summary of the findings. The three most popular products accepted in barter deals were advertising or media space with 59 percent of all the respondents ranking it first followed by BTL marketing/events/promotional items and travel and hospitality. BTL marketing/ events/promotional items were ranked first and second by 21.3 percent and 45.9 percent respectively of the practitioners. The popularity of travel and hospitality was consistent across the rankings with 14.8 percent of the practitioners ranking it first, 16.4 percent ranking it second and 18.0 percent ranking it third. Fixed assets and programming/editorial/creative works were the least common items accepted in barter deals with only 7 and 5 firms respectively ranking it among their top three items. The fixed assets cited included motor vehicles, furniture and various types of equipment.

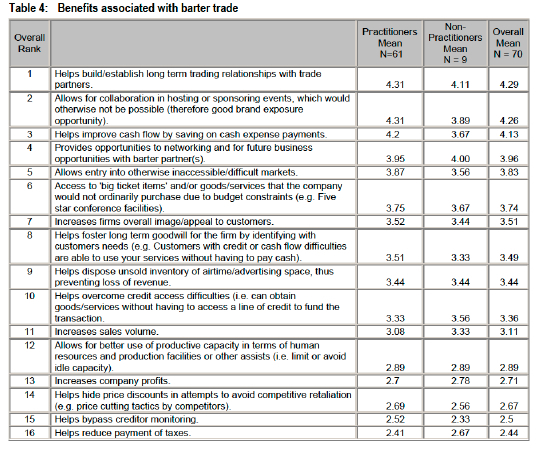

Table 4 presents findings relating to benefits associated with barter trade. As the statements were measured on five point Likert scale, mean values of 5 or to the nearest of 5 meant very high levels of agreement, those of 4 or to the nearest of 4 indicated agreement with the statement while those of 3 or to the nearest of 3 indicated a neutral position. Mean values of 2 or the nearest of 2 indicated disagreement with the statement while those less than 1.5 indicated strong disagreement.

From the results it is clear that there are many benefits associated with barter trade. The respondents in general agreed to statements with an overall rank of 1 to 8 as the main benefits associated with barter trade. The overall ranking was according to the overall mean values. The main benefits associated with barter trade in order of importance include the fact that it helps build long term trading relations; allows for collaboration in hosting or sponsorship events which would otherwise not be possible; helps improve cash flow by saving on cash expense payments; provides opportunities to networking and for future business opportunities with barter partners; allows entry into otherwise inaccessible/difficult markets; helps an organisation access big ticket items that the company would not ordinarily purchase due to budget constraints and the fact that it helps foster long term goodwill for the firm by identifying with customers' needs.

The results show that respondents were in overall terms neutral with regards to 7 statements relating to benefits of barter trade. These included the fact that barter helps dispose unsold inventory of airtime/advertising space, thus preventing loss of revenue; helps overcome credit access difficulties; increases sales volume; allows for better use of productive capacity in terms of human resources and production facilities or other assists (i.e. limit or avoid idle capacity); increases company profits; helps hide price discounts in attempts to avoid competitive retaliation and helps bypass creditor monitoring. These 7 factors had mean values of 3 or to the nearest of 3. The neutral mean values in these factors was mostly because of mixed feelings between the respondents. While other respondents felt that factors were important benefits many others did not consider the factors as important benefits of barter trade resulting in overall mean values of neutral.

It is important to note that out of the 16 statements on the benefits of barter trade respondents disagreed with only one statement. This was the fact that barter trade helps reduce payment of taxes which had a mean value of 2.44. This is likely due to the fact that for accounting purposes barter income is by law expected to be treated as equivalent to cash income. In such situations there can thus be no major tax benefits associated with barter trade (Cresti 2005:1955).

A look at the mean values of practitioners of barter trade in comparison with those of non-practitioners shows that there were many similarities between the two groups in how they perceived the various benefits. This is because the mean values of almost all statements were often very close to each other. Both groups rated the fact that barter trade helps build/establish long term trading relationships with trade partners as the most important benefit associated with barter trade. The same benefits that were rated in the top six by practitioners were also in the top 6 of the non-practitioners although not in exactly the same order.

A closer look at the mean values for the two groups shows that practitioners, just like with the overall mean values, agreed with 8 statements relating to benefits of barter trade, were neutral on 7 statements and disagreed with reduction in payment of taxes as a benefit of barter trade. Non-practitioners on the other hand agreed with 7 statements as benefits of barter trade were neutral on 8 statements and disagreed with one statement being a benefit associated with barter trade. The 7 statements they agreed with included the top six in the overall ranking and the fact that barter trade helps overcome credit access difficulties which was ranked 10th in the overall rankings and had an overall mean value indicating neutral position. They disagreed with the fact that barter trade helps bypass creditor monitoring.

CONCLUSIONS, LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

From the findings it is clear that barter trade is a very common practice in the South African media industry and its popularity cuts across all main media sectors, as well as across firms of all sizes. It can also be concluded that barter trade is a practice that will continue to be commonly practiced in the industry. This is evident from the fact that most practitioners indicated that they will continue to engage in the practice while some non-practitioners indicated that they will consider the practice in future. Barter trade is however very much shrouded in secrecy as many of the organizations involved in the study showed a lot of concern for confidentiality by asking for more assurance that they will not be individually identified. Efforts aimed at bringing the practice out in the open especially at industry level, would go a long way in enhancing better management of the practice as well as ensuring transparency.

Most of the barter trade in the media industry involves other firms in the same industry. This is reflected from the fact that advertising/media space is the most popular product received in barter exchanges. A wide range of other products are also accepted in barter exchanges. These include travel and hospitality services as well as various types of fixed assets. As most companies are constrained by marketing budgets in their efforts to promote their products/services, for firms that are not in the media industry willingness of firms in the industry to accept barter deals offers opportunities to promote their organisations and/or products/services without any cash outlays. The findings show that both practitioners and non-practitioners perceive many benefits in barter trading.

The major limitation of the current study is the small number of non-practitioners relative to practitioners. This made it difficult to compare the two groups using high level statistical tools. Future research should try and investigate non-practitioners opinions and perceptions regarding barter trade using a bigger sample. The investigation can further explore why despite the many benefits perceived, barter non-practitioners may still not want to engage in the practice. As the current study focused on barter trade in the media industry, future studies looking at the practice in other industries would help bring profound insight into the practice in general.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BARR S. 1993. Trading Places: Barter Re-enters Corporate America. Management Review, August:30-34. [ Links ]

CAMPBELL D. 2009. Corporate Trade or Barter: Financial Flexibility for Today's Economy. American Association of Advertising Agencies AAA, Bulleting No. 7008:1-16. [ Links ]

CELLARIUS B. 2000. You Can Buy Almost Everything With Potatoes: An Examination of Barter During Economic Crisis in Bulgaria. Ethnology, 39(1):73-92 [ Links ]

CRESTI B. 2005. U.S. Domestic Barter: An Empirical Investigation. Applied Economics, 37(17):1953-1966. [ Links ]

EGAN C. & SHIPLEY D. 1996. Strategic Orientations Towards Countertrade Opportunities in Emerging Markets. International Marketing Review, 13(4):102-120. [ Links ]

FERENCE M. 2009. Fight Economic Woes by Trading your way to New Business. Promotional Products Association Magazine. [Online] Available from Url: http://www.ppbmag.com accessed 2nd November 2009. [ Links ]

HEALEY N. 1989. Two Pigs for a Personal Computer. Management Today, October:116-110. [ Links ]

HEALEY N. 1996. Why is Corporate Barter? Business Economics, 31(2):36-46. [ Links ]

HENNART J. 1990. Some Empirical Dimensions of Countertrade. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(2):243-270. [ Links ]

KASSAYE W. & VACCARO J. 1993. TV Stations' Use of Barter to Finance Programs and Advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research, May/June:40-48. [ Links ]

LECRAW D. 1989. The Management of Countertrade: Factors Influencing Success. Journal of International Business Studies, 20(1):41-59. [ Links ]

LIESCH P. & PALIA A. 1999. Australian Perceptions and Experiences of International Countertrade with Some International Comparisons. European Journal of Marketing, 33(5/6):488-511. [ Links ]

LONDON COUNTERTRADE ROUNDTABLE. 2007. Countertrade Frequently Asked Questions. [Online] Available from Url: http://www.londoncountertrade.org, accessed 2nd November 2009 [ Links ]

MARDAK D. 2002. The world of Barter. Strategic Finance, 84(1):44-48. [ Links ]

McCAMMON V. 2006. Bartering for your Business. Michiana Business Publications, 18(12):70. [ Links ]

ORME D. 2004. Barter Transactions provide Growth Opportunities for your Clients. Journal of Banking and Financial Services, 118(4):70-74. [ Links ]

SMALL BUSINESS ASSOCIATION. 2008. The Ancient Art of Bartering Goes Mainstream. [Online] Available from Url: http://www.theinternetbarterexchange.com, accessed 11 November 2009. [ Links ]

STOUT J. 2007. Bartering can Improve our Sales Volumes. BarterNews. [Online] Available from Url: http://www.barternews.com accessed 3rd November 2009. [ Links ]

STUBIN L. 2004. Media Bartering and Brand Marketing. American Marketing Association (Chicago) Best Practice. [ Links ]

UNIVERSAL BARTER GROUP. 2008. Barter Industry Statistics. [Online] Available from Url: http://www.universalbartergroup.com, accessed 11th November 2009. [ Links ]