Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of Contemporary Management

versión On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.6 no.1 Meyerton 2009

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The influence of occupational status, income and academic qualifications on the relationship intention of South African short-term insurance clients: an exploratory study

TFJ SteynI; PG MostertII; JNW de JagerIII

ISchool of Business, Cameron University, Oklahoma

IIWorkwell: Research Unit for Economic and Management Sciences, North-West University

IIIWorkwell: Research Unit for Economic and Management Sciences, North-West University

ABSTRACT

Building long-term relationships with clients benefit businesses in many ways. However, clients do not necessarily want to establish long-term relationships with businesses. The objective of this research was to establish whether clients with different occupational status, income and academic qualifications display significant differences between the five relationship intention constructs of involvement, expectations, forgiveness, feedback and fear of relationship loss. A non-probability sample of 114 clients of a short-term insurance broker completed self-administered questionnaires. Findings indicate that, for a sample of high relationship intention clients of the insurance broker (including retirees, economically active clients, different income category clients and clients with different educational profiles) no practically significant differences were found on any of the relationship intention constructs.

Key phrases: Relationship Intention; Relationship Marketing; Short-term Insurance; Occupation; Income; Academic qualifications

1 INTRODUCTION

Relationship marketing is a marketing orientation in which businesses seek to develop close interaction with selected clients, suppliers and competitors to create reciprocal value through co-operative and collaborative efforts (Hollenson 2003:10). Relationship marketing is also described as a process of creating, maintaining and enhancing strong value-laden relationships with clients and other stakeholders (Kotler & Armstrong 2001:9).

Relationship marketing therefore focuses on both client relations and expanding profitable relationships with suppliers, partners, employees and even competitors. The aim with these relations is to establish a successful mutually-beneficial relationship that delivers value to clients (on the one hand) and increased sales, market share and profits to businesses (on the other). Client value is found in longterm business-client relationships that result in familiarity, personal recognition, discounts, credit advances or even friendship for clients (Disney 1999:491). It is, however, important to note that all clients do not necessarily want to engage in a long-term relationship with a business. In this regard Styles and Ambler (2003) indicated that transactional and relational approaches to marketing can coexist in the same market, while Gopalakrishma Pillai and Sharma (2003) found that mature relationships can revert from a relational to a transactional orientation. Clients favouring a transactional approach in their interactions with a business will not want to invest in building a relationship with the business. In such circumstances even a business that values relationships (with all the concomitant benefits to itself and clients) will not be able to develop a long-term relationship with clients who do not want such a relationship. It therefore becomes important to look at relationship marketing from clients' perspective in order to identify those clients who are positively predisposed to long-term relationships with businesses (Donaldson & O'Toole 2002:8).

This article reports on research in which short-term insurance clients' relationship intention is investigated to establish whether clients with differences in occupational status, income or academic qualifications exhibit practically significant differences for the constructs constituting relationship intention.

2 LITERATURE BACKGROUND

A number of theoretical concepts important to this article are subsequently discussed. The notion of relationship marketing with its constituent concepts of trust and commitment is firstly explored. Some parallels between relationship marketing and the concept of service quality are then highlighted. The relationship between socio-economic status, income and occupational status in a developing country such as South Africa is then indicated, and the dimensions of relationship intention are finally explained.

2.1 Relationship marketing

To be relationship oriented, a business must look beyond single transactions. It must accept that every client represents a potential stream of future revenue and long-term earnings (Barnes 2000:19).

Service encounters force the buyer (client) into intimate contact with the seller (supplier). This facilitates the development of social bonds between clients and suppliers (O'Mally & Tynan 2003:35). Hansen et al (2002:494) argue that service encounters are social encounters by nature. Grönroos (2000:6-7) found that a relationship may emerge if several service encounters follow each other in a continuous or discrete fashion.

Relationship marketing benefits businesses in a number of ways (Barnes 2000:19; Bowen & Shoemaker 2003:31; Christopher et al 2002:8; Grönroos 2000:131; Lamb et al 2008:11; Lovelock & Wirtz 2007:352; O'Mally & Prothero 2004:1287; Payne 2006:9; White & Schneider 2000:241). These benefits include reduced costs, increased client spending, client referrals and charging price-premiums. Enjoyment of relationship benefits by as business, however, depends on increased client retention.

Clients experience at least three sets of benefits from maintaining relationships with businesses, namely confidence, social and special treatment benefits (Ruiz et al 2007:1091). However, clients will only commit to a relationship with a business if that business provides superior value to them (Chiou 2004:687). A number of authors support the notion that sustained value creation to the client provides the basis for successful long-term business-client relationships (see for example Bowen & Shoemaker 2003:36; Christopher et al 2002:21; Ferrel & Hartline 2005:121; Lamb et al 2008:10).

Due to the personal nature of services, service businesses are in a better position to establish profitable, value creating long-term relationships with their clients. This is especially true of financial services (of which short-term insurance services are examples), as many clients lack the required technical knowledge and skills to confidently invest in and buy financial products (Sharma & Patterson 2000:473). Short-term insurance clients must therefore trust their financial advisors, as establishing long-term client relationships in the short-term insurance industry depends on the degree to which clients trust their insurance advisors or brokers. The trust requirement becomes even more important in the South African short-term insurance environment, where crime levels are high and motor vehicle accidents occur frequently (SAIA 2007:13-14).

Morgan and Hunt (1994) constituted the commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing arguing that commitment and trust are the two imperatives for building strong client relationships. These concepts are still acknowledged as fundamental for constituting successful business-client relationships (see Hansen & Riggle 2009; Lay-Hwa Bowden 2009) and are subsequently defined.

2.1.1 Commitment

An important element required for establishing long-term business-client relationships is relationship commitment. This refers to a willingness or desire to maintain a relationship (Fullerton 2005:100; Grönroos 2000:38). Commitment encourages clients to resist attractive short-term alternatives from other businesses in favour of the expected benefits of supporting long-term relationships with existing service providers (Morgan & Hunt 1994:22). The level of relationship commitment therefore determines the strength of the relationship. This, in turn, influences clients' intention to remain in a relationship with a business. The longer the relationship, the more service businesses retain clients and the more clients repeat transactions. This results in higher potential business profitability (Guitierrez et al 2004:355).

2.1.2 Trust

Due to the uncertainty and risk associated with acquiring services, clients have an inherent need to trust their service provider to deliver the desired service outcome (Coulter & Coulter 2002:35-36). Trust is perhaps the single most important relationship marketing tool available to a service business (Chiou 2004:688; Grönroos 2000:31; Sirdeshmukh et al 2002:15). Signalling trust to clients is a vital first step for service businesses to establish co-operative behaviour and is therefore necessary in establishing long-term relationships. The major benefit for service businesses in building trust with clients is that the latter will have a higher tolerance towards the business and would be more forgiving towards the business' service failures (Ball et al 2003:1275).

2.2 Service quality

Without high standards of service quality a business would jeopardize its client relationships. Service quality is often conceptualized as the difference between client expectations and the business' actual service performance (Pride & Ferrel 2006:374). Meek et al (2005:163), however, indicate that service quality depends heavily on the match between expectations of service quality and client perceptions of the service. The client's perception of the actual service performance therefore determines the quality of a particular service.

Apart from aiding the establishment of long-term client relationships, improved service quality also raises client satisfaction levels. This, in turn, leads to relationship strength, which results in relationship longevity and client relationship profitability (Ferrel & Hartline 2005:125; Meek et al 2005:217). It is thus evident that client satisfaction plays a key role in client retention. It is important to note that the benefits flowing from improved service quality remind us of the overall benefits attributed to relationship marketing.

2.3 Occupational status, income and academic qualifications

Van Aardt (2008:10-15) found that the most important predictors of living standards in South Africa are (in declining order) income, race, education, type of residential area, employment and province of residence. Therefore, in the South African context, income would play a greater role in determining a person's social class. However, a change in income not only affects an individual's ability to buy, but also alters lifestyle expectations. Income levels influence clients' wants and determine their buying power. This would also explain why it is still the single most used segmentation base for research purposes (Lamb et al 2008:169).

However, an individual's occupational status mostly determines his/her income level. Academic qualifications, in turn, determine occupational opportunities. Three of the six predictors identified by Van Aardt (2008), i.e. income, education and employment, are therefore accounted for in this article as these predictors would affect clients' spending power.

2.4 Relationship intention

According to Kumar et al (2003:667, 669) relationship intention refers to a client's intention to build a relationship with a business while buying and using a product or service from that business. Clients with high relationship intention have a high affinity towards, are emotionally attached to, and display greater trust in the business.

A client's relationship intention is measured by five constructs (Kumar et al 2003:670), namely clients' involvement with the product or service, their expectations of the product or service, their willingness to forgive service failures on the part of the business, whether they provide feedback to the business and whether they would fear the loss of a relationship with the business' employees or with the business itself. These five constructs are subsequently discussed.

2.4.1 Involvement

Clients' involvement in the product or service is defined as "the degree to which a person would willingly intend to engage in a relationship activity without any coercion or obligation" (Kumar et al 2003:670). However, according to Kalamas et al (2002:294) clients' motivation to participate in the service production and delivery process, vary.

Involvement determines clients' interest in relationships with service providers, as more involved clients express greater willingness to maintain their relationship with the business (Mukherjee 2007:11; Varki & Wong 2003:87). Client involvement also influences their expectations of relational activities that the service provider initiate. More involved clients are more inclined to form realistic expectations about the business (Varki & Wong 2003:90). Highly involved clients' propensity to build longterm relationships with and form more realistic expectations of the business is advantageous to the business.

2.4.2 Expectations

According to Lovelock and Wirtz (2007:46) and Coye (2004:55), expectations reflect an individual's subjective probabilities about the current or future existence of a particular state of affairs - therefore what the client ideally want. Kumar et al (2003:670) state that clients inevitably develop expectations when they buy a product or service from a business. Clients who are more concerned with the quality of the product or service will have higher expectations of the business as well as a higher intention to build a relationship with it (Kumar et al 2003:670). Client expectations depend on their perception of the service quality the business provides, their image of the business, word-of-mouth about the business, tangible cues linked to the business and service promises the business makes (Boshoff & Staude 2003:11; Kalamas et al 2002:295; Ojasalo 2001:208).

2.4.3 Forgiveness

In a business-client setting, forgiveness constitutes loyal clients' willingness to move beyond a business' service failure (Robbins & Miller 2004:97). De Coverly et al (2002:24) maintain that strong relationships between clients and businesses would reduce the chance of clients defecting. It would thus seem that those clients who are more "resistant" or forgiving in terms of service failures also show high relationship intention. Kumar et al (2003:670) support this by stating that those clients who are willing to build a relationship with a business are also more willing to continue their support of the business even when their expectations are not always fulfilled.

2.4.4 Feedback

A business' service recovery efforts can only be directed to clients who provide feedback to the business about a service failure. Satisfactory service recovery will motivate clients to be more loyal to the business and trust it more (Weun et al 2004:133). Kumar et al (2003:670) therefore maintains that clients who are inclined to give either positive or negative feedback to the business also exhibit a higher relationship intention.

2.4.5 Fear of relationship loss

Fear of relationship loss represents a switching cost which prevents clients from supporting a competing business' products or services (Aydin et al 2005:91; Caruana 2002:256). Caruana (2002:258) also views "psychological or emotional discomfort due to the loss of identity and breaking of bonds which consist of personal relationship loss and brand relationship costs" as relational switching. Kumar et al (2003:670) argue that clients with high involvement fear losing their relationship with a business and subsequently show a high intention towards relationship building with the business. This emotional attachment to the business serves as a relational switching cost. Clients will be reluctant to switch because they fear the loss of emotional attachment - either with the brand or the business' employees with whom the client interacts.

3 PROBLEM STATEMENT AND OBJECTIVE

Even if a business is highly relationship oriented, the success of its relational initiatives will depend on the client's willingness to engage in a relationship with the business. The business perspective on relationship marketing is well researched, but a need exists to explore relationship building from clients' perspective. This article is a step in that direction, as it hypothesizes that clients with different demographic profiles will exhibit different attitudes towards the respective relationship intention constructs discussed in section 2.4.

The objective of this article is therefore to investigate whether differences exist between certain demographic variables of short-term insurance clients (e.g. occupational status, income and academic qualifications) and aspects of their relationship intention towards a short-term insurance broker.

4 METHOD

4.1 Sample

Short-term insurance refers to insurance products such as household and vehicle insurance (Bitter 2004:29). This article investigates the relationship intention of shortterm insurance clients of a national short-term insurance broker in South Africa. A non-probability sampling technique, namely convenience sampling, was used. The reason why convenience sampling was used was to protect the privacy of customers of the insurance broker. The insurance broker was concerned about the privacy of its customers if a probability sampling technique were to be used. The insurance broker was only willing for its customers to be surveyed if it could be done on a voluntary basis without the researchers having any direct access to customer information. It was therefore agreed that 360 questionnaires were to be distributed to the 18 branches of the short-term insurance broker. Twenty questionnaires were to be completed by clients at each of the 18 respective branches situated in different geographic locations throughout South Africa. The questionnaires were placed at the reception desk of each of the branches and branch managers were asked to encourage customers who visited the branches in person to complete a questionnaire. From the 360 questionnaires distributed, 114 usable ones were returned from 10 branches of the short-term insurance broker nationwide.

Due to the non-probability nature of the sample results from this study are not representative of the insurance industry as a whole or other service industries.

4.2 Data collection

The questionnaires distributed to the clients were self-administered. These types of questionnaires were used because of its cost-effective nature (Cooper & Schindler 2003:341; Struwig & Stead 2001:86, 88). Moreover, self-administered questionnaires are also perceived to be more impersonal, providing the respondent with more anonymity (Cooper & Schindler 2003:341). It therefore fitted the purpose of the research to collect data on personal information, feelings and attitudes.

4.3 Questionnaire

The questionnaire measured respondents' relationship intention in terms of the relationship intention constructs of involvement, expectations, forgiveness, feedback and fear of relationship loss (see section 2.4 above). The questionnaire was adapted from Kumar et al. (2003:675), and consisted of Likert-type scales to measure the relationship intention constructs as well as multiple choice questions to gather respondents' biographic and demographic information.

4.4 Data analysis

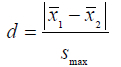

Effect sizes analysis measuring Cohen's d-values was used to determine practically significant differences between the means of different demographic groups. Effect sizes (d-values) were calculated with the following formula (Cohen 1988:20-27):

where:

• d = effect size;

• χ1 - x2 is the difference between means of two compared groups; and

• smax is the maximum standard deviation of the two compared groups.

Effect sizes were interpreted as follows (Cohen 1988:20-27; Ellis & Steyn 2003: 51-53):

• d = 0.2 indicating a small effect with no practical significance;

• d = 0.5 indicating a moderate effect; and

• d = 0.8 or larger indicating a practically significant effect.

Effect size analysis was more appropriate than tests for statistical significance, because (Steyn 2005:3-4; Steyn & Ellis 2006:172-175):

• The questionnaire was non-standardized. Non-standardized questionnaires do not always clearly indicate the difference in means between groups. In such circumstances, effect sizes can be used to judge the practical significance of differences in means between groups;

• The realized sample of respondents (n=114) was small and the line of inquiry (i.e. relationship intention of short-term insurance clients) was new in the context of relationship marketing. In such circumstances, effect sizes rather than tests for statistical significance identify important differences between groups; and

• The use of a non-probability sample rendered it inappropriate to calculate statistical significance. When dealing with non-probability samples, effect sizes offer a much better alternative to judge significance.

5 RESULTS

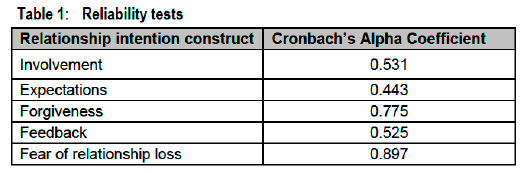

Table 1 indicates the results of reliability tests conducted on the questionnaire.

It is evident from Table 1 that the Cronbach's Alpha values were, in three instances, lower than the accepted cut-off point of 0.7 (Field 2005:668). This might be attributed to the exploratory nature of the study and the fact that (as per the questionnaire of Kumar et al [2003]) only three items were used per construct. Field (2005:668), however, states that low Cronbach's Alpha values can be expected in most social science studies. Field (2005:668) also indicates that values of smaller than 0.7 might be acceptable in cases where a diversity of psychological constructs such as attitudes and opinions are measured (as was the case in this study).

5.1 Occupational status

From the results it was found that nearly 41 percent of respondents are retirees. This constitutes the largest category in the sample. Another significant group represented in the sample is administrative personnel (18 percent). Because of the substantial portion of retirees who participated in the study, the researchers decided to treat them as a separate category versus the economically active population. Table 2 provides the relationship intention scores for retirees versus economically active respondents.

Table 2 illustrates that no practically significant effect sizes were found when comparing retirees to the rest of the sample in terms of their relationship intention scores. However, a relatively higher d-value of 0.43 was found when comparing these two groups in terms of their forgiveness. Retirees showed a lower forgiveness score of 53.7 percent, compared to the economically active respondents (who showed a lower fear of relationship loss score [59.2 percent]). The highest score amongst the respective relationship intention constructs for retirees was for feedback (85.2 percent), while the economically active respondents also indicated feedback as their highest score (88.1 percent).

5.2 Income

When considering respondents' gross monthly income, it was found that 16 percent earn less than R5 000 per month. The highest percentage of respondents earn between R5 000 and R10 000 per month. Income groups were used to compare respondents in terms of their relationship intention scores (depicted in Table 3). For this purpose, income groups above R15 000 per month were collapsed into one income category.

5.2.1 Income groups and involvement

As shown in Table 3, no significant effect sizes were found when comparing different income groups in terms of their involvement. However, relatively higher d-values were obtained when involvement of the lowest income group (less than R5 000 per month) was compared to income groups above R5 000 per month. The most noticeable involvement score (73.6 percent) was for the highest income group (more than R15 000 per month), while the lowest involvement score (69.4 percent) was for the lowest income group (less than R5 000 per month).

5.2.2 Income groups and expectations

A moderate effect size (d=0.47) was found when comparing those who earn less than R5 000 per month with those who earn between R10 001 and R15 000 per month. These two groups also showed the highest and lowest expectation scores, with 63 percent for those who earn less than R5 000 per month, and 56.2 percent for those who earn between R10 001 and R15 000 per month.

5.2.3 Income groups and forgiveness

As indicated in Table 3, no practically significant effect sizes were found when comparing the different income groups in terms of their forgiveness. The highest forgiveness score (61.3 percent) was calculated for the highest income group (those who earn more than R15 000 per month), while the lowest score (57.6 percent) was calculated for the lowest income group (those who earn less than R5 000 per month).

5.2.4 Income groups and feedback

In terms of feedback, medium-effect d-values were found when comparing those who earn between R10 001 and R15 000 per month with the income groups between R5 000 and R10 000 per month (d=0.68) and more than R15 000 per month (d=0.62). The other d-values were all practically insignificant. The highest feedback score (mean=89.4 percent) was calculated for those who earn between R5 000 and R10 000 per month, while the lowest feedback score (80.0 percent) was calculated for those who earn between R10 001 and R15 000 per month.

5.2.5 Income groups and fear of relationship loss

As shown in Table 3, medium effect sizes were obtained when fear of relationship loss scores were compared between the lowest income group (i.e. those who earn R5 000 or less per month) and those who earn between R10 001 and R15 000 per month (d=0.57); and those who earn more than R15 000 per month (d=0.45). The other d-values were all practically insignificant. The highest fear of relationship loss score (69.3 percent) was calculated for the lowest income group (those who earn less than R5 000 per month), while the lowest fear of relationship loss score (56.8 percent) was found for those who earn between R10 001 and R15 000 per month.

5.3 Academic qualifications

When considering respondents' educational qualifications it was found that 40 percent of the respondents obtained a matric (12th grade) qualification as highest academic qualification, 9 percent acquired a certificate, while the majority of the sample (51 percent) obtained some form of tertiary (higher education) qualification. For convenience purposes, the classification of educational qualifications is divided between non-tertiary qualifications (ΝΤΕ) and tertiary qualifications (TE).

Table 4 depicts the Rl scores in terms of the two categories of qualifications.

As Table 4 illustrates, no practically significant d-values were obtained when the two categories of tertiary qualifications were compared in terms of their relationship intention scores. However, a relatively larger d-value of 0.32 was found when comparing these two groups in terms of their forgiveness scores. Those without a tertiary education showed a forgiveness score of 56.0 percent, while those with a tertiary education showed a forgiveness score of 62.2 percent. Those respondents without a tertiary education indicated the highest score among the respective relationship intention constructs for feedback (88.2 percent), while their lowest overall score was for forgiveness (56.0 percent). Those respondents with a tertiary education also provided the highest score among the respective relationship intention constructs for feedback (86.9 percent) while their lowest overall score was for expectations (58.5 percent).

6 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.1 Occupational status

Nearly 41 percent of the sample consisted of retirees. This group displays lower forgiveness for service failure than the rest of the sample. This could be due to their higher price sensitivity caused by the loss in income from earning a monthly pension instead of a monthly salary.

However, this does not imply that retired couples and individuals are not a profitable market for short-term insurance brokers. Foscht et al (2005:17) found that businesses must prioritize price and guarantee when developing marketing strategies for older people. Brokers should thus primarily focus on pricing when they market products to retirees. They must also consider retirees' price sensitivity when building long-term relationships with them. They should develop insurance products that fall within retirees' price range and make arrangements that will minimize price fluctuations in monthly premiums for these clients.

The short-term insurance broker should also consider offering additional products or services, such as health insurance, to retirees. Partnerships with health insurance companies to offer specialized health insurance products to these clients might be a viable route.

However, it is important to note that in this study no practically significant differences were detected between retirees and economically active clients of the short-term insurance broker for any of the relationship intention constructs. For purposes of this study, where both retirees and economically active clients showed a relatively high relationship intention (i.e. 68.0 percent for the retirees and 68.3 percent for the economically active population - see Table 2) no practically significant differences therefore exist between these client groups on any of the relationship intention constructs.

6.2 Income

Most of the respondents who participated in the survey (64 percent of the sample) earn between R5 000 and R10 000 per month and it would appear that those who earn the lowest income (less than R5 000 per month) are not as involved as those who earn a higher income (between R5 000 and R10 000 per month). This could be attributed to the fact that lower income groups show higher price sensitivity. The assumption could be made that these clients are more prone to switch to alternative service providers based on price differences. It would seem that involvement increases as the client's income increases. However, the lowest income group recorded higher scores in terms of fear of relationship loss.

Clients in the lowest income segment may not have the capital to expose themselves to the risk and uncertainty associated with terminating their current relationship with the broker and initiating a new relationship with another insurance provider. However, the process of switching to alternative insurance providers is facilitated by the fact that consumers could relatively easy compare the rates alternative insurance providers offer (e.g. comparing quoted rates on the Internet).

Furthermore, lower income segments are less likely to spend as much on short-term insurance as those in higher income segments. This is because people with higher monthly incomes tend to own more valuable vehicles and properties and more expensive household contents, are more likely to participate in employer sponsored health coverage and are more likely to feel the need to protect their assets through life insurance. However, the broker must also take into account that, as people progress in their careers, they could significantly increase their monthly income. Building long-term relationships with clients within the lower income segments may therefore provide a positive future return on investment for the business. The broker should therefore identify those clients who show high potential future earnings. Demographics such as age and academic qualification could prove helpful in this regard.

However, it is important to note that in this study no practically significant differences were found between clients of different income categories for any of the relationship intention constructs. For purposes of this study, where clients of different income categories all showed a relatively high relationship intention (i.e. between 65.8 percent and 69.3 percent for the different income categories - see Table 3) no practically significant differences therefore exist between these client groups on any of the relationship intention constructs.

6.3 Academic qualifications

Those clients who have obtained a tertiary qualification (TE clients) showed higher forgiveness scores than those without a tertiary qualification (NTE clients). It is reasonable to assume that TE clients are more tolerant of service failures than NTE clients and the broker should bear this in mind when building long-term relationships with these categories of clients.

Both TE and NTE clients had the highest score for feedback among the RI constructs. The broker should carefully manage service recovery and take special care to communicate effectively with clients. This is especially true in cases of service failures and explaining reasons behind these failures.

It is important to note that in this study no practically significant differences were found between TE and NTE clients of the short-term insurance broker for any of the relationship intention constructs. For purposes of this study, where both TE and NTE clients showed a relatively high relationship intention (i.e. 69.4 percent for TE and 67.4 percent for NTE clients - see Table 4) no practically significant differences therefore exist between these client groups on any of the relationship intention constructs.

7 LIMITATIONS, CONTRIBUTION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

This study showed two limitations, namely the low Cronbach's Alpha values on some of the relationship intention constructs and the relatively small sample size biased towards pensioners. Possible reasons for the first shortcoming were explained above (see section 5). However, in a study on the relationship intention of new motor vehicle owners, Mentz (2007) adapted the questionnaire used in this study and improved the Cronbach's Alpha values.

This article hypothesized that clients with different demographic profiles will exhibit different attitudes towards the respective relationship intention constructs. From the results of this exploratory study it can, however, be deduced that no such practically significant differences exist. No practically significant differences were found for clients of the short-term insurance broker for any of the relationship intention constructs on any distinction between retirees and economically active clients, between different income category clients or between tertiary qualified and non-tertiary qualified clients. These findings support the findings by Steyn et al (2008) which neither found any practically significant differences for any of the relationship intention constructs and another set of biographic and demographic variables (including length of relationship with the broker, respondents' gender and age). Given the limitations of the study discussed above, it can be stated that (for purposes of the exploratory study) the relationship intention of (high relationship intention) clients of the short-term insurance broker is neither influenced by differences in respondents' occupational status, income or academic qualifications, nor by differences in their gender, age or length of relationship with the broker.

Future research must continue to measure the relationship intention of clients in other industries as well as other sectors in the insurance industry (such as life insurance). Clients with low relationship intention scores should also be included in future studies to ascertain whether practically significant differences exist between the respective relationship intention constructs for low relationship intention clients. If no such practically significant differences are found for low relationship intention clients, the relationship intention (as measured by the five relationship intention constructs) of low and high relationship intention clients should be compared. If practically significant differences exist between the relationship intention constructs of low and high relationship intention clients, relationship intention might prove to be a viable alternative market segmentation base for businesses.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AYDIN S., OZER G. & ARASIL O. 2005. Client Loyalty and The Effect of Switching Costs as a Moderator Variable: A Case in the Turkish Mobile Phone Market. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 23(1):89-103. [ Links ]

BALL D., COELHO P.S. & MACHAS A. 2003. The role of communication and trust in explaining client loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 38(9/10):1272-1293. [ Links ]

BARNES J.G. 2000. Secrets of Client Relationship Management: Its all About How You Make Them Feel, New-York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

BITTER N. 2004. The State of the South African Short-Term Insurance Market. Cover, 13(12):28-32. [ Links ]

BOSHOFF C. & STAUDE G. 2003. Satisfaction with service recovery: its measurement and its outcomes. South African Journal of Business Management, 34(3):9-16. [ Links ]

BOWEN J.T. & SHOEMAKER S. 2003. Loyalty: A Strategic Commitment. Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 44(5/6):31-46. [ Links ]

CARUANA A. 2002. Service Loyalty: The Effects of Service Quality and the Mediating Role of Client Satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing, 36(7/8):811-829. [ Links ]

CHIOU J. 2004. The Antecedents of Clients' Loyalty Toward Internet Service Providers. Information & Management, 41(6):685-695. [ Links ]

CHRISTOPHER M., PAYNE A. & BALLANTYNE D. 2002. Relationship Marketing: Creating Stakeholder Value. Oxford: Butterworth-Heineman. [ Links ]

COHEN J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

COOPER D.R. & SCHINDLER P.S. 2003. Business Research Methods. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

COULTER K.S. & COULTER R.A. 2002. Determinants of Trust in a Service Provider: The Moderating Role of Length of Relationship. Journal of Services Marketing, 16(1):35-50. [ Links ]

COYE R.W. 2004. Managing client expectations in the service encounter. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(1):54-71. [ Links ]

DE COVERLY E., HOLME N.O., KELLER A.G., MATTISON T.F.H. & TOYOKI S. 2002. Service Recovery in the Airline Industry: Is it as Simple as 'Failed, Recovered, Satisfied?' Marketing Review, 3(1):21-38. [ Links ]

DISNEY J. 1999. Client Satisfaction and Loyalty: The Critical Elements of Service Quality. Total Quality Management, 10(4/5):491-497. [ Links ]

DONALDSON B. & OTOOLE T. 2002. Strategic Market Relationships: From Strategy to Implementation. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

ELLIS S.M. & STEYN H.S. 2003. Practical Significance (Effect Sizes) Versus or in Combination with Statistical Significance (p-values). Management Dynamics, 12(4):51-53. [ Links ]

FERREL O.C. & HARTLINE M.D. 2005. Marketing Strategy. Ohio: Thomson South-Western. [ Links ]

FIELD, A. 2005. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. London: SAGE publications. [ Links ]

FOSCHT A., ANGERER T., SWOBODA B. & MOAZEDI L. 2005 Loyalty Marketing for 50+ Consumers: Findings for a Better Understanding of Loyalty Behaviour. European Retail Digest, Spring, (45):14-17. [ Links ]

FULLERTON G. 2005. The Service Quality-Loyalty Relationship in Retail Services: Does Commitment Matter? Journal of Retailing and Client Services, 12(2):99-111. [ Links ]

GOPALAKRISHMA PILLAI K. & SHARMA A. 2003. Mature Relationships: Why does Relational Orientation turn into Transactional Orientation. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(8):643-651. [ Links ]

GRÖNROOS C. 2000. Service Management and Marketing: A Client Relationship Management Approach. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

GUITIERREZ S.S.M., CILLIAN J.G. & IZQUIERDO C.C. 2004. The Client's Relational Commitment: Main Dimensions and Antecedents. Journal of Retailing and Client Services, 11 (2004):351-367. [ Links ]

HANSEN J.D. & RIGGLE R.J. 2009. Ethical Salesperson Behavior in Sales Relationships. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29(2):151-166. [ Links ]

HANSEN H., SANDVIK K. & SELNES F. 2002. When Clients Develop Commitment to the Service Employee: Exploring the Direct and Indirect Effects on Propensity to Stay. Advances in Client Research, 29(1):494. [ Links ]

HOLLENSON S. 2003. Marketing Management: A Relationship Approach. Harlow: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

KALAMAS M., LAROCHE M. & CEZARD A. 2002. A Model of the Antecedents of Should and Will Service Expectations. Journal of Retailing & Client Services, 9(6):291-308. [ Links ]

KOTLER P. & ARMSTRONG G. 2001. Principles of Marketing, Upper Saddle River. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

KUMAR V., BOHLING R., & LADDA R.N. 2003. Antecedents and Consequences of Relationship Intention: Implications for Transaction and Relationship Marketing. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(8):667-676. [ Links ]

LAMB C.W., HAIR J.F., MCDANIEL C., BOSHOFF C. & TERBLANCHE N.S. 2008. Marketing. 3rd Edition. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

LAY-HWA BOWDEN J. 2009. The Process of Customer Engagement" A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 17(1):63-74. [ Links ]

LOVELOCK C. & WIRTZ J. 2007. Services Marketing: People, Technology, Strategy. 6th Edition. New Jersey: Pearson-Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

MEEK H., MEEK R., PALMER R. & PARKINSON L. 2005. Managing Marketing Performance. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heineman. [ Links ]

MENTZ M.H. 2007. Die Verhoudingsvoorneme van Motorkopers in die Vrystaat (The Relationship Intention of Motor Vehicle Buyers in the Free State). Magister Commercia dissertation, Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. [ Links ]

MORGAN R.M. & HUNT S.D. 1994. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3):20-38. [ Links ]

MUKHERJEE A. 2007. It's crunch time - Doritos make an impact at the Super Bowl. Brand Strategy, 215:11, Sep. [ Links ]

OJASALO J. 2001. Managing client expectations in professional services, Managing Service Quality, 11(3): 200-212. [ Links ]

O'MALLY L. & PROTHERO A. 2004. Beyond the Frills of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Business Research, 57(11):1286-1294. [ Links ]

O'MALLY L. & TYNAN C. 2003. Relationship Marketing. In The Marketing Book. Baker, M.J., ed., Oxford: Butterworth-Heineman. [ Links ]

PAYNE A. 2006. Handbook of CRM: achieving excellence in customer management. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Butterworth-Heineman. [ Links ]

PRIDE W.M. & FERREL O.C. 2006. Marketing: Concepts and Strategies. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

ROBBINS T.L. & MILLER J.L. 2004. Considering Client Loyalty in Developing Service Recovery Strategies. Journal of Business Strategies, 21(2):95-109. [ Links ]

RUIZ D.M., CASTRO C.B. & ARMARIO, E.M. 2007. Explaining market heterogeneity in terms of value perceptions. Service Industries Journal, Dec, 27(8):1087-1110. [ Links ]

SAIA. See South African Insurance Association.

SHARMA N. & PATTERSON P.G. 2000. Switching Costs, Alternative Attractiveness and Experience as Moderators of Relationship Commitment in Professional, Client Services. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 11(5):470-490. [ Links ]

SIRDESHMUKH D., SINGH J. & SABOL B. 2002. Client Trust, Value, and Loyalty in Relational Exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 66(1):15-37. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN INSURANCE ASSOCIATION. 2007. SAIA Annual Review. Available from: http://www.saia.co.za/member-section/57.html [ Links ]

STEYN H.S. 2005. Handleiding vir Bepaling van Effekgrootte-Indekse en Praktiese Betekenisvolheid (Manual for the Determination of Effect Size Indices and Practical Significance). Potchefstroom: Statistical Consultation Service, North-West University (Potchefstroom Campus). [ Links ]

STEYN H.S. (JR) & ELLIS S.M. 2006. Die Gebruik van Effekgrootte-Indekse by die Bepaling van Praktiese Betekenisvolheid. (The Use of Effect Size Indices in the Determination of Practical Significance) Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Natuurwetenskap en Tegnologie, 25(3):172-175. [ Links ]

STEYN T.F.J., MOSTERT P.G. & DE JAGER J.N.W. 2008. The influence of length of Relationship, Gender and Age on the Relationship Intention of Short-Term Insurance Clients: an Exploratory Study. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, NS11 (2):139-156. [ Links ]

STRUWIG F.W. & STEAD G.B. 2001. Planning, Designing and Reporting Research. Cape Town: Pearson Education South-Africa. [ Links ]

STYLES C. & AMBLER T. 2003. The Coexistence of Transaction and Relational Marketing: Insights from the Chinese Business Context. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(8):633-642. [ Links ]

VAN AARDT C.J. 2008. Determining the predictors of living standards in South Africa: a real world econometric approach. South African Business Review, 12(1):1-17. [ Links ]

VARKI S. & WONG S. 2003. Client Involvement in Relationship Marketing of Services. Journal of Service Research, 6(1):83-91. [ Links ]

WEUN S., BEATTY S.E. & JONES M.A. 2004. The Impact of Service Failure Severity on Service Recovery Evaluations and Post-Recovery Relationships. Journal of Services Marketing, 18(2):133-146. [ Links ]

WHITE S.S. & SCHNEIDER B. 2000. Climbing the Commitment Ladder: The Role of Expectations Disconfirmation on Client's Behavioral Intentions. Journal of Service Research, 2(3):240-253. [ Links ]