Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.6 no.1 Meyerton 2009

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Transformation strategies can change organisations to be effective

GC Mwanza

Strategic Management, Preston University

ABSTRACT

This paper is concerned with the management activities involved in changing strategies and address important issues to do with the structuring of organizations and the resourcing of strategies, both important in change. However, designing a structure and putting in place appropriate resource do not of themselves ensure that people will make a strategy happen. This begins by explaining important issues that need to be considered in diagnosing the situation an organization faces when embarking on strategic change, in terms of the types of change required, the variety of contextual and cultural factors that need to be taken into account, and the forces blocking or facilitating change. This paper discusses the management of strategic change in terms of the styles of transformation change and the role played by the strategic leaders and other change agents in managing strategic change.

Key phrases: Change agent, external environment, Meta environment, Meso environment, Micro environment and planned change

INTRODUCTION

Strategy is the direction and scope of an organization over the long term, which achieves advantage in a changing environment through its configuration of resources and competences with the aim of fulfilling stakeholder expectations. Strategic management is made at a number of levels in organizations. Corporate level strategy is concerned with an organization's overall purpose and scope; business level (or competitive) strategy with how to compete successfully in a market; and operational strategies with how the resources, processes and people can effectively deliver corporate and business strategies. Strategic management is distinguished from day-to-day operational management by the complexity of influences on decisions, the organization wide implications and their long term implication. Strategic management has three major elements: understanding the strategic position, making strategic choices for the future and managing strategy in action. The strategic position of an organization is influenced by the external environment, internal strategic capability and the expectations and influence of stakeholders. Managing strategy in action is concerned with issues of structuring, resourcing to enable future strategies and managing change. Strategic management is also concerned with understanding which choices are likely to succeed or fail.

Drucker (2008:15) informs that a business exists only for the purpose of creating and keeping a customer. The conception of its vision and mission statements, goals and strategies is a manifested attempt to fulfil this purpose. The business needs an internal organisation capable of amassing and positioning the resources necessary for the delivery of its purpose through its strategies. The design considerations for this internal organisation of social structures, systems and order are influenced by the business's relative position to its external environment (Porter 1998:30). The organisation has to be modified regularly, and at times transformed, when this relative position is shifted by the turbulence in the environment.

Organisational scientists have suggested a number of approaches, like culture change, self-design and organisational learning (Waddell, Cummings & Worley 2007:67), for planned change. While the management vocabulary and jargons used in these approaches may differ, they do follow a general pattern. There is the process of entering into a psychological and financial contract with the change practitioners and agents, determining the actual problem, gathering and processing data to validate and scope the problem, providing findings, conclusions and recommendations to the change agents, designing and implementing interventions for change, and finally evaluating the outcomes of these interventions and determining if the change has successfully taken place and in the intended shape.

Businesses could engage in two different magnitudes of planned change (Waddell et al 2007:69). When social mechanisms, such as assumptions, values, norms, and artefacts, are adjusted, we said that these businesses have successfully conducted a transformational change. Transformational change goes beyond fine-tuning the status quo or making the existing organisation better. It shifts the core business philosophy and model, makes alterations to its strategies, and reorganises social arrangements by introducing new forms of organisational behaviours to shape current ones. These actions change the orientation of the business.

Businesses are more inclined to transformational change when they face severe threats to their survival. Tushman, Newman & Romanelli (2000:35) have identified three types of disruption that make the likelihood of such a change a potent option for businesses. These are the industry discontinuities that are caused by the reconfiguration of environmental elements, shifts in product life cycle as products and services mature in the consumer market, and changes in the internal politics of the business as different social actors engaged in activities that mobilise the support for or opposition against goals, policies, and rules to create new means to get a stake (Lawler & Bacharach 1998:40) of the capital (Thomson 1999:50) in the organisation.

Those businesses that are only capable of adjusting and modifying some of these social mechanisms to meet external environmental requirements but leaving the paradigm of perceiving the environment, thinking about strategies, and behaving in the organisation largely intact are incremental in nature. In this instant, big developmental efforts are usually restricted and limited by those with vested power, sentience, and expertise in the existing organisational arrangements. The members in the social order are more predisposed to fine-tune the social structures and morale code to protect their own personal power and influence, and to avoid the erosion and curtailment of the length and depth of their managerial discretion (Hambrick & Finkelstein 1987:41) than to change them drastically.

However, the central theme for most successful businesses is their ability to make use of their external environment as agility drivers (Sharifi, Colquhou, Barclay & Dann 2001:66) to create the necessary internal strategic capability and capacity to stay ahead of the competition. To do this, they have to constantly reconfigure and reconstitute their internal structures and social mechanisms to give each of their businesses their unique character and competitive advantage. Also, they need to do this as anticipatory as the uncertainties of the change and as fast as the pace of these changes to be effective.

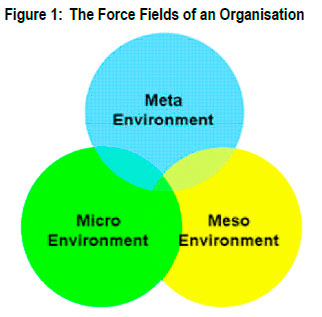

Nevertheless, it is difficult to contemplate the idea of an external environment comprising of political, economical, social and technological elements working independently from each other. According to Frenkel (2003:23), an organisation should be seen as a structure embedded in three force fields (Figure 1).

This diagram was conceptualised by the author using the ideas of the 'Three Force Fields' proposed by S. J. Frenkel in his 2003 article on 'The Embedded Character of Workplace Relations'.

The Meta environment is driven by global events and the availability of new technologies. When the global economic-competitive environment changes from one of optimising performance around quality and cost to creating products and services specifically for the needs and wants of the customers, new manufacturing paradigm will have to be invented and the complementing technologies will have to be found and introduced to the organisation (Sharifi et al 2001:32) to make the paradigm work. Disruptive innovations (Christensen 1997:85) are also capable of displacing industries. Dominant businesses have let their guards down through ignorance or arrogance and were incapable of sensing the extent new businesses, operating with new technologies, could shape the terrain in the industry and displace the incumbents eventually. They have not anticipated how these new businesses, which produce lower quality products and services, could rapidly learn to rival the dominant players with products and services of far superior value (Kim 2005:45).

The Meso environment is driven by elements that impact the business's value-chain, which comprises of structures and processes that are distributed transnationally to fully account for the comparative advantage each of these nations has to offers. The value-chain is essential for the acquisition and translation of raw materials and work-in-progress from different parts of the world into the final products and services that are stored for and delivered to the global consumer. The application of new technologies in the value-chain will change the task and labour processes in its structures (Taylor 1998:24), displacing people, and making the business more effective and efficient.

The Micro environment is driven by the local conditions in which the business resides and operates, by the market structure of labour in that country, and by the work that needs to be carried out in that business for that country. While the change may call for adjustments in the labour processes, their actual execution and implementation may have to be adapted to local conditions because the embedded institutional structures are unique in each location where the business operates (Woywode 2002:68).

The examples listed above show that these drivers are interrelated and they interact with each other in some kind of a cause and effect order, and at times seem to be hierarchically arranged. Not only do the drivers affect the structures within their own force field, they affect the corresponding drivers in other force fields as well, much like the earthly tectonic plates that are constantly expanding onto their own and at the same time encroaching into their adjacent pieces. Clegg, Courpasson and Phillips (2006:10) point out that the birth, grow and demise of organisations is a result of 'economic agents calculating, miscalculating, and constructing the historical accumulation of capital' that are obtained from and grew out of their environments. However, while the organisation is a historically produced object, they indicate that 'its existence is not necessary determined by anything nor is it freely constructed'. Otherwise, we will not be capable of introducing any kind of planned change if the potential growth trajectory of a business is pre-determined by its environment.

Nevertheless, this freedom to reorganise is restricted by the influences of the drivers from the various force fields. These make things a bit more challenging as one cannot be sure which environmental element is actually the driving mechanism in the industry, especially if one is to read each of the force fields individually. It means that one is required to look at change not just by its parts but through its dynamics as well so that the 'whole' story could be told through the relationships and interactions of the drivers in all of the force fields. By catering to the parts and dynamics of the total environment, we could continue to keep the missions, goals and strategies of the business aligned to its purpose and vision.

Lewin (2003:46) suggests that when the forces for change and forces for status quo are equal, the behaviours in the social system will exist in a quasi-stationary equilibrium state. To change in such a circumstance, one has to increase the forces for change or diminish the opposing forces that prevent change from happening. This is a simple way of describing how change could be initiated but its execution is less straightforward for a business wanting planned adaptations and transformation with its external environment. This notion of upsetting the balance is problematic. It presents a view that businesses are capable of accurately predicting and forecasting the emergence and ascendancy of internal organisational and external environmental triggers, and capable of offsetting and adapting ingrained social forces and arrangements to these changes with will and ease. This may not be that evident since emotions and behaviours of specific individuals, groups or networks are not that clearly read and easily instrumented as compare to the ease of manipulating systems and processes.

The main reason for these challenges is that the quasi-stationary equilibrium only opens a temporal access where the change practitioners are barely given the time to accurately read the business's condition and health. There will always be pressure from the economic agents' calculated and miscalculated acts to cause the rearrangement of the social order and elements in each of the external environment. These actions shift and change the current social and environmental climate, policies, structures and maturity level. As the social structure and environment adapt within, its interfacing elements will interact and realign with their counterparts in another environmental system, all in a struggle to create and hold onto some sort of temporal internal and aggregated homeostasis again. Thus, most of the time change practitioners are only able of producing a bounded reality (Simon 1996:15) of the social and environmental conditions of the business useful in deciding the best type of 'force' to apply, the amount of 'force' to apply, and the amount of time the 'force' should be applied to enable the change to reach a self-sustainable state.

One know that the organisational change is successful when each member in the business is found to have modified his or her behaviours and acquired new habits as a result of the interventions. However, all these could be just good acting (Fineman 1993) and a matter of executing effective impression management. Those who eventually come under pressure to perform will crack down and private feelings of irritation, anger and rebellion will come forth resulting in him or her not able to 'survive' the change. The knowledge why and how these survival strategies are used are useful lessons to the change agents, who want a successful implementation of new strategies in a changing environment. However, the information on the casual mechanisms that produce individual change is unavailable and it makes designing, monitoring and controlling the change over a period of time a challenge.

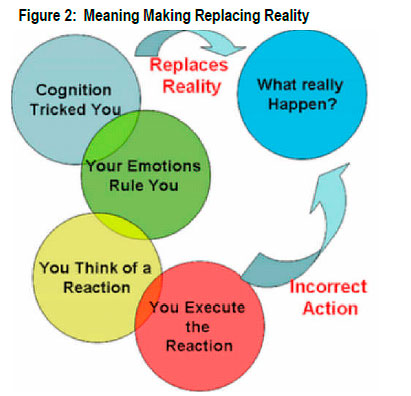

This diagram was created by the author, who is deeply influenced by the concepts of psychodynamics as discussed by organisational writers like S. Fineman in his book 'Organisations as Emotional Arenas' in 1993.

One reason for this missing piece of knowledge is the complex nature of the social order in an organisation. Because one have a tendency to view the organisation mechanically rather than organically (Thaw 2002:68), we see organisations as being rational and objective. This denies us to opportunity to perceive the organisation as a meaning making (Fineman 1993:29) machine (Figure 2) comprising of people with emotions and feelings. Emotion and cognition is intertwined. Ideas are laden with feelings, and feelings germinate ideals in a culturally contextualised environment.

The social order and structures that influence the organisation are of human creation and they are at the same time influencing the process of creating new structures and meanings. When combined, they produce trajectories that lead to different kinds of outcome from that single point of origin. By factoring this aspect of organisation into the mechanical equation, the quasi-stationary equilibrium makes the reading of the organisation even more difficult if the change practitioners only examine the parts and not the dynamics. When the observable rational part of the system is seemed to be in temporal homeostasis, the invisible irrational meaning making portion could be largely in disarray and keeping the overall social systems in the organisation from ever reaching a state of equilibrium and order. The change practitioners could be misled by what seem to be stable on the surface.

The social order evolves when resources that oppose policies and create access to existing and new capital are mobilised. New morale codes of shame and guilt are drawn up (Fineman 1999:56) as well. These are carried out, between social actors, through micro agreements, deals, compromises, and trade offs conducted out of the perceived fear of uncertainty and chaos that may impact their relative status in a socially constituted world (Fineman 1993:32). These actions could rearrange power positions and order in the hierarchy, and the actions are asserted through strict emotional control and suppression to maintain an appearance of sanity and stability that are dominating and mutually exclusive in nature. The need to be detached emotionally from the organisation is to maintain personal control and power. This attempt to control the private personal realm while claiming the wish to unleash it with change appears to provoke strong resistance from employees (Taylor 1998:76). Why is there so much of resistance? People see their organisation as themselves. In it, they find meaning to their own identity and existence. There are deep fear of nothingness and being in an organisation and supporting a culture of self-deception is to avoid acknowledging the 'truth of one's own powerlessness' to a change that is constantly giving them difficulties. To be in control is to survive by maintaining and protecting themselves organisationally, and this strategy can be seen as a resistance to change (Fineman 1993:43). This results in other social actors wanting to avoid true personal change even in the midst of the social rearrangement. When such emotional dispositions are kept below the surface and unable to be authentically addressed, people become resigned, passionless, defensive and hostile towards the organisation and the people in and around it. These are energy draining and the actors become withdrawn emotionally from the organisation to avoid having to feel about the things that are happening around them (Beatty 2000:12). When these emotions are politically driven and limiting, they will suppress ideals and feelings (Beatty 2000:14). If change practitioners (Waddell, Cummings & Worley 2007:54) ignore these dynamics in the emotional realm of change, the unresolved emotions and feelings could 're-enter the process by the backdoor' (Beatty 2000:21).

Perhaps, it comes as no surprise that planned change tends to be seen as a rationally controlled mechanism that operates in an orderly fashion. However, because emotion and cognition is intertwined at the workplace, planned change takes on a more chaotic quality. It is characterised by shifts in goals, appearances of discontinuous activities, and occurrences of surprising events. These, whether as a single event or combined occurrences, are capable of affecting the mood and motivation of the change agents who are calling for and leading the change. Emotion and cognition are entwined (Fineman 1999:13). Emotion could get in the way of rationality even though the emotional process can serve rationality.

These indicate that by looking at the pieces of the change is to discount the synergistic and multiplier effects of the interactions between pieces in the whole system as it works towards an unstable equilibrium. This is further complicated by the process of creating the change itself. In causing the organisation to move with its shifting environment, it is injecting new forces that upset the social structures and order, which introduces even greater uncertainty to the relationships and interactions amongst the pieces. We need to examine the parts and the whole in tandem. The change itself as well as its scalability throughout the system is important studies as it is the ripple effects of change that produce unexpected outcomes that usually caught organisations unaware and unprepared for their new challenges.

This is where the difficulties of using the approaches of planned change become more apparent. These approaches have mostly discounted the situational factors that demand modifications in the methodologies at the generic level. Also, there are deficiencies in the current body of knowledge on how the stages of each planned change approach may vary across all change situations since there are differences within the same industry that saddles across a number of nations. Even within the industry, there could be sectional differences (Woywode 2002:40). This makes the adoption of best management practices from other leading businesses without consideration of their unique institutional settings dangerous. Even when these practices are a good way of reducing environmental complexity for managerial decision making, of reducing the risks of been criticised since the best methods are followed, and of increasing efficiency because they contain valuable managerial wisdom (Woywode 2002:42), they may lead change agents into a false sense of being right about the appropriate sequence of change for their organisations.

So, what is this 'dynamics' that has been mentioned in much of this essay? According to Bourdieu (Thomson 1999:17; Beatty 2000:28), change takes place when social actors struggle with each other and differentiate themselves into dominant and subordinated positions played out based on the type and amount of capital they hold. The field where these games are held is made up of networks of social relationships, social spaces and topology of power. In this structured space, players, having subscribed to its rules, adopt behavioural strategies of conservation, subversion and succession to improve the social positions they currently held in the pecking order and increase the amount of economic, symbolic, cultural or social capital they already accumulated. It is these acts of increasing self-worth, personal influence and power, and social ranking that make the playing field fully dynamic and ever changing (Thomson 1999:40). Since these networks of social relationships, social spaces and topology of power are by-products of human interactions in the organisation, the field which the social actors operate in is a kind of emotional arena (Fineman 1993:60) where cultural labels are applied to specific constellation after their appraisal of the situation, changes to their bodily sensations, and exhibiting their freedom or inhibition to express certain gestures to one another (Beatty 2000:69). In fact, in the name of granting the feeling of autonomy and empowerment in the new workplace to encourage talent retention and performance, it has been found in reality that the introduction of these changes is in itself injecting more emotions and they demand the deployment of emotional labour (Taylor 1998:4) amongst the personnel as their prime survival strategy in their organisation.

Given this dynamism, we cannot accurately predict how the tectonic plates will move and the effects their drivers have on the total environment. For where change could be anticipated and planned, there will be unplanned change that we must respond and react to. One could view organisational transformation as being ahead of it environmental changes. The other sees organisational adaptations as akin to 'just-in-time' adjustments coming just behind the arrival of the change in the environment.

To conduct 'just-in-time' adaptations, businesses need both the capability to respond as the change occurs and the capacity to change once the direction is decided. This calls for another perspective about organisational change, one which is more strategic and responsive as compare to the simple planned tactical approach of upsetting the balance of various force fields to effect progression.

We may conduct planned interventions for changes that are easily identified and anticipate. The business may create contingency or 'drawer' plans that could be rapidly deployed and executed by using existing resources or resources that were acquired for their flexibility for multiple uses to deal with these predictable changes. This means the organisation needs to position spare or flexible resources or mechanisms for calling on external capacity ahead of the change to enable the initiation these drawer plans. This is a capacity based solution to change.

While these management concepts are globally diffused, they do call for local adaptations because of institutional differences. 'Isomorphic and idiosyncratic' tendencies have been observed at the same time when such concepts are implemented. Thus, it is not wise to look at best practices as if they are the Holy Grail for everything (Woywode 2002:48). The resilience of national cultures will persistently cause variations in businesses across countries and even for businesses operating in the same industry. These external influences will take the organisation towards different paths and consequences even when the organisational practices are the same.

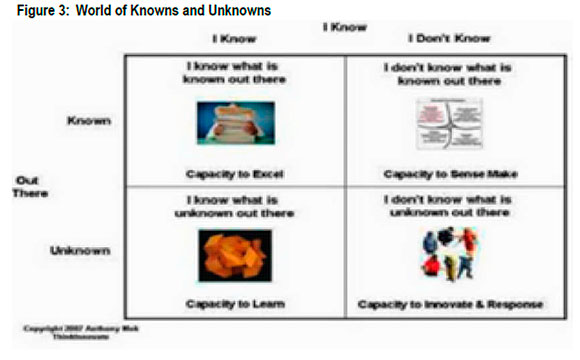

The ideas used by the author to conceptualise this diagram can be traced to the Department of Defence (USA) News Briefing conducted by the Secretary of Defence, Donald H. Rumsfeld, in 2002.

A similar version of this body of knowledge has been found in works produced by Meyer, Loch, & Pich (2002) and Chapman & Ward (2003).

However, not all events fall into this category. There are many unpredictable and unprecedented events (Figure 3), which could dislocate business operations and disable its ability to survive. This requires a different strategy which calls for the business to use its capability rather than capacity to reconfigure the organisation in a reactive but responsive way. This means business must be able to respond by been inventive and innovative on-the-go with what they already have as the change occurs outside normal expectations caused by the dynamics from the various environments.

When the science of change is not fully understood and grounded by empirical research, doing planned change in a highly dynamic environment becomes formidable task. This may suggests that planned change has not totally account for dynamism in change and calls to question the sustainable qualities of planned change on the adaptation and transformation of the organisation to its new environment.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BEATTY, B. 2000. The Emotions of Educational Leadership: Breaking the Silence, International Journal of Leadership in Education, 3(4):331-357. [ Links ]

CHAPMAN C. & WARD S. 2003. Project Risk Management: Processes. Techniques and Insights, Wiley [ Links ]

CHRISTENSEN C.M. 1997. The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

CLEGG S.R., COURPASSON D. & PHILLIPS N. 2006. Power and Organisations. London: SAGE Publications. Powerand Organisational Forms, Chapter 11:320-340. [ Links ]

DRUCKER P.F. 2008. The Essential Drucker: The Best of Sixty Years of Peter Drucker's Essential Writings on Management (Paperback). Collins; Reissue edition, July 22, 2008. [ Links ]

FINEMAN S. 1993. Organisations as Emotional Arenas, in S. Fineman (Ed.), Emotion in Organisations. London: Sage:9-35. [ Links ]

FINEMAN S. 1999. Emotion and Organising, in S. R. Clegg & C. Hardy (Eds.), Studying Organisation: Theory and Method. London: Sage:288-310. [ Links ]

FRENKEL S.J. 2003. The Embedded Character of Workplace Relations, Work and Occupations, 30(2):135-153. [ Links ]

HAMBRICK D.C. & FINKELSTEIN S. 1987. Managerial discretion: a bridge between polar views of organizational outcomes, in Research in OrganizationalBehaviour, Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press, 9:369-406. [ Links ]

KIM C.W. 2005. Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make Competition Irrelevant. Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

LAWLER E.J. & BACHARACH S.B. 1998. Political Action and Alignments in Sociology. Research in Sociology of Organisations, 2:83-107. [ Links ]

LEWIN K. 2003. Quasi-Stationary Social Equilibria and the Problem of Permanent Change. Chapter 6, "Human Relations in Curriculum Change" In Readings in Social Psychology by Theodore M. Neweomb and Eugene L. Hartley, pp340-44. Co-Chairmen of Editorial Committee, Henry Holt and Co: [ Links ]

MEYER A.D., LOCH C.H. & PICH M.T. 2002. Managing Project Uncertainty: From Variation to Chaos, MIT Sloan Management Review, 2002: Winter. [ Links ]

PORTER M.E. 1998. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. Free Press. [ Links ]

RUMSFELD D.H. 2002. DoD News Briefing Secretary of Defense, Donald H.Rumsfeld, Available from http://www.defenselink.mil/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=2636. [ Links ]

SHARIFI H., COLQUHOU, G., BARCLAY I. & DANN Z. 2001. Agility Manufacturing: A Management and Operational Framework, Processing Institute of Mechanical Engineers, 215:857-869. [ Links ]

SIMON H.A. 1996. Models of My Life. The MIT Press. [ Links ]

TAYLOR S. 1998. Emotional Labour and the New Workplace, in P. Thompson & C. Warhurst (Eds), Workplaces of the Future, London: Macmillan, pp. 84-103. [ Links ]

THAW D. 2002. Stepping into the Rivers of Change in M. Edwards and A. Fowler The Earthscan Reader on NGO Management. London: Earthscan: 146-163. [ Links ]

THOMSON P. 1999. Reading the Work of School Administrators with the Help of Bourdieu: Getting a "Feel for the Game", Paper presented at the AARE and NZARE joint conference (Melbourne). [ Links ]

TUSHMAN M.L., NEWMAN W.H. & ROMANELLI E. 2000. Convergence and Upheaval: Managing the Unsteady Pace of Organizational Evolution, California Management Review, 29(1):22-39. [ Links ]

WADDELL D.M., CUMMINGS T.G. & WORLEY C.G. 2007. Organisation, Development and Change. 3rd Edition, Asia Pacific, Australia and Singapore: Thomson. [ Links ]

WOYWODE M. 2002. Global Management Concepts and Local Adaptations: Working Groups in the French and German Car Manufacturing Industry, Organisation Studies, 23(4):497-524. [ Links ]