Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.6 no.1 Meyerton 2009

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The use of the focus group technique in management research: the example of renewable energy technology selection in Africa

M-L BarryI; H SteynII; A BrentIII

IDepartment of Engineering and Technology Management, University of Pretoria

IIDepartment of Engineering and Technology Management, University of Pretoria

IIIDepartment of Engineering and Technology Management, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Quantitative management research on the African continent is often hampered by the lack of large data sets and the unreliability of electronic as well as conventional communication. This paper advocates the use of qualitative methods, in particular the focus group technique, to overcome these difficulties. The focus group technique has been extensively used in social sciences research and in this paper its use in management research is investigated and applied. The paper further advocates the use of triangulation to improve the reliability of qualitative management research. An example of the selection of renewable energy technology in Africa is used as basis for this investigation. In this case the focus group technique was used to identify thirty-eight factors during the exploratory phase of a larger research effort. The focus group technique was used in conjunction with the nominal group technique. The authors make recommendations on how the focus group technique can be successfully applied in management research.

Key phrases: Management research, focus group technique, nominal group technique, quantitative vs. qualitative techniques

INTRODUCTION

Any chosen research method will have inherent shortcomings and the choice of method will always limit the conclusions that can be drawn from the results (Sandura & Williams 2000). For this reason it is essential to obtain corroborating evidence by using a variety of methods. This is also known as triangulation. The use of a variety of methods in examining a topic might result in findings with a higher external validity (Sandura & Williams 2000). The study by Sandura and Williams (2000) of patterns of research methods in management research across the middle 1980s and 1990s indicated that researchers are increasingly employing research strategies and methodological approaches that comprise triangulation.

The important factors that need to be taken into account in research design are: generalisability to the population that supports external validity, precision in measurement, control of behavioural variables which affect the internal and construct validity, and realism of context (McGrath (1982) as cited Sandura & Williams 2000).

In a study done by Sandura and Williams (2000) to determine research strategies employed in management research from 1985 to 1987 and 1995 to 1997 they found that the methods shown in Table 1 are mostly used for management research and a mapping is done in terms of generalisability, realism of context and precision of measurement for each research method according to their findings.

It is clear from Table 1 that no single research method addresses all the important factors that must be taken into account for research design, even when conducting quantitative research.

Qualitative research can be conducted successfully where large data sets are not available, and the use of several research methods i.e. triangulation will improve the research validity.

According to the definitions given by Scandura and Williams (2000), the focus group technique is a judgment task and is thus rated as 'medium' in generalisability, low' on realism of context and 'medium' on precision of measurement. When using triangulation, methods that strengthen realism of context should thus be paired with the focus group technique.

On the African continent, the performance of quantitative research is normally hampered by several factors, including the lack of large data sets and unreliability of electronic as well as conventional communication. For this reason, qualitative research methods are favoured in management research in this environment. This paper discusses the use of the focus group technique during the exploration phase of a study on the selection of renewable energy technology in Africa.

FOCUS GROUP TECHNIQUE

The focus group technique is also called the 'group depth interview' or the 'focused interview' in the literature. Different authors ascribe the origin of the focus group method to different sources. Hutt (1979) states that the technique grew out of group therapy techniques applied by psychiatrists, Robinson (1999) avers that the method originated with market researchers in the 1920s, whilst Blackburn (2000) credits Merton and his colleagues with developing the technique for data collection on the effectiveness of World War II training and propaganda films.

Regardless of the origin of focus groups, the technique has been used successfully in many areas of research. These include: determination of respondent attitudes and needs (Robinson 1999), exploration and generation of hypotheses (Gibbs 1997; Blackburn 2000) development of questions or concepts for questionnaire design (Gibbs 1997), interpreting survey results (Blackburn 2000), pretesting surveys (Ouimet et al 2004), counselling (Hutt 1979), testing research methods and action learning, identification of strengths and weaknesses and information gathering at the end of programmes to determine outputs and impacts (Robinson 1999).

Focus group research has not only been applied in various types of research, but also in many research fields including: social sciences, medical applications (Gibbs 1997), market research, media, political opinion polls, government improvements, business, consulting, ethics, entrepreneurship research (Gibbs 1997), education (Ouimet et al 2004) and healthcare (Robinson 1999).

The benefits of taking part in a focus group, for the participants include the opportunity to be involved in decision making, the fact that they feel valued as experts, and the chance to work in collaboration with their peers and the researcher Gibbs 1997). Interaction in focus groups is crucial as it allows participants to ask questions as required, and to reconsider their responses (Gibbs 1997).

By definition, focus groups are organised discussions or interviews, with a selected small group of individuals (Blackburn 2000; Gibbs 1997), discussing a specific, predefined and limited topic under the guidance of a facilitator or moderator (Blackburn 2000; Robinson 1999). A focus group is also a collective activity where several perspectives on the given topic can be obtained, and where the data is produced by interaction (Gibbs 1997). According to Merton and Kendall (1946 as cited in Gibbs 1997), a focus group is made up of individuals with specific experience in the topic of interest, which is explored during the focus group session.

Patton (1990, as cited in Robinson 1999), avers that the focus group has the following purposes: basic research where it contributes to fundamental theory and knowledge, applied research to determine programme effectiveness, formative evaluation for programme improvement, and action research for problem solving.

One of the common uses of focus groups is during the exploratory phase, to inform the development of later stages of a study (Bloor et al 2001; Robinson 1999). One of the four basic uses of a focus group given by Morgan (1998) is that of problem identification.

In this study, the focus group technique was used for basic research with the goal of contributing to the fundamental theory and knowledge of important factors for the selection of energy technologies in Africa during the exploratory phase.

The advantages of the focus group method are numerous and include:

(i) It is an effective method of collecting qualitative data since common ground can be covered rapidly and inputs can be obtained from several people at the same time (Hutt 1979; Ouimet et al 2004).

(ii) During discussions, the synergistic group effort produces a snowballing of ideas which provokes new ideas (Blackburn 2000; Gibbs 1997).

(iii) Data of great range, depth, specificity and personal context is generated (Blackburn 2000).

(iv) In the process, the researcher is in the minority and the participants interact with their peers (Blackburn 2000).

The disadvantages include:

(i) Not all respondents are comfortable with working in a group environment and some may find giving opinions in the bigger group intimidating (Gibbs 1997; Ouimet et al 2004).

(ii) The outcome can be influenced by the 'group effect' in that the opinion of one person might dominate, that some might be reluctant to speak and that an opportunity might not be given for all participants to air their views (Blackburn 2000).

(iii) The researcher has less control over the data than in, for example, a survey due to the open-ended nature of the questions (Gibbs 1997).

The disadvantages can be mitigated by ensuring that the moderator has sufficient skills, reliable data collection and the use of rigorous analytical methods (Blackburn 2000). The use of triangulation of methods can also ensure that point (ii) above is mitigated.

NOMINAL GROUP TECHNIQUE

When conducting a focus group, various methods can be used to elicit information from the participants. Delbecq et al (1975) compares two of the methods, namely an interacting process and a nominal process. The interacting process takes the format of a brainstorming session amongst a group of individuals.

Osborn (1957 as quoted in Delbecq 1975) found brainstorming groups produce significantly more ideas than individuals working on their own. The nominal group process differs from the interacting process in that individuals first generate ideas in the presence of each other but by writing down their ideas independently. These written down ideas are then discussed in the group. Nominal group techniques have been found to produce more ideas relative to a specific problem than interacting groups (Delbecq et al 1975).

Some of the disadvantages of the focus group, discussed above, can be further mitigated by using the nominal group technique in conjunction with the focus group technique as was done by Ouimet et al (2004). This ensures that all participants air their views and that the ideas of one participant do not dominate.

APPLICATION OF A COMBINED FOCUS AND NOMINAL GROUP TECHNIQUE: SELECTION OF RENEWABLE ENERGY TECHNOLOGIES IN AFRICA

The greatest challenge faced in sub-Saharan Africa today, is reaching a maintainable rate of positive economic growth in order to cope with urban growth, as well as to industrialise and provide basic energy services to off-grid rural communities (UNECA 2007).

Energy is essential for economic development (IEA 2004). The difference between the energy supply and demand in Africa has widened in the last three decades and experts predict that this disparity will continue translating into energy poverty and a hindrance to socio-economic growth (UNEA 2007).

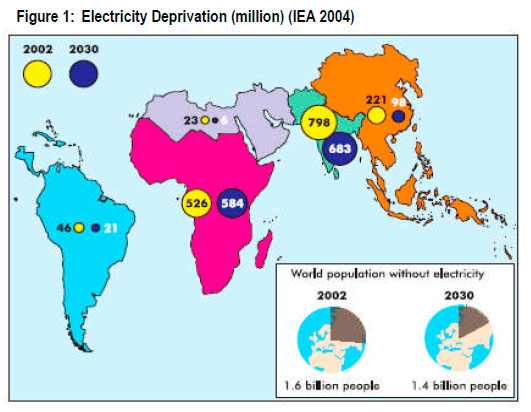

The map of the world population without electricity for 2002 and projected to 2030 is shown in Figure 1. The startling reality is that it is projected that electrification levels in sub-Saharan Africa will decrease rather than increase from now to 2030.

The study used as an example in this paper was undertaken to determine the factors that are the most important for the selection of renewable energy technologies in order to ensure efficient use of scarce resources in Africa. The study followed a triangulation of methodologies with the use of the focus group, Delphi study and case study methodologies.

FOCUS GROUP METHODOLOGY

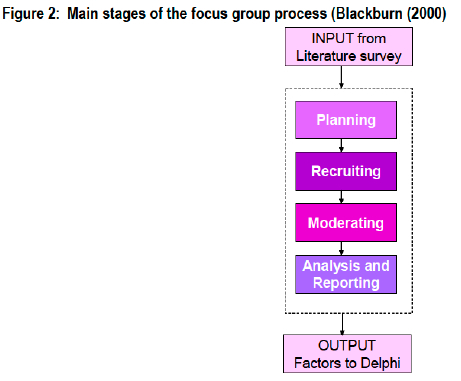

The main stages of the focus group process are: planning, recruiting, moderating, and analysis and reporting as depicted in Figure 2 (Blackburn 2000). During the planning stage, the researcher familiarised herself with the focus group technique and did a literature survey on sustainable energy selection factors.

The role of the moderator or facilitator is critical to the success of the focus group (Blackburn 2000; Delbecq et al 1975). The moderator must clearly state the expectations and purpose of the group, facilitate interaction (Gibbs 1997) by outlining the topics to be discussed and controlling the direction of the conversation (Blackburn 2000). The moderator is the conversational controller (Hutt 1979) who must promote open debate by using open-ended questions and probe deeper as to the motivations of the participants (Gibbs 1997). The moderator must further ensure that the conversation does not drift, but that the group addresses the key topics of interest (Blackburn 2000; Delbecq et al 1975).

Robinson (1999) further emphasises that focus groups are in-depth and open-ended group discussions which implies that the focus group is not a very structured method. Hutt (1979) advocates that focus groups should be semi-structured rather than highly structured. The use of an interview guide or list of questions to be answered during the focus group is recommended (Blackburn 2000; Delbecq et al; Robinson 1999). It is important to limit the number of questions. Whether the interview is more or less structured will depend on the specific application (Blackburn 2000).

This focus group was structured by preparing a presentation during the planning stage that was used to inform the participants on the purpose of the focus group. The literature survey during the planning stages identified the eleven factors listed in Table 2.

Focus groups can consist of pre-existing groups if those groups have the expertise required (Bloor et al 2001:23). For this study, an existing group in the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) was selected due to the fact that these scientists all have interest and experience in the field of sustainable energy.

In the literature, various sizes of focus groups are recommended. These include four to fifteen participants (Gibbs 1997), six to ten (Blackburn 2000), and up to fourteen (Ouimet et al 2004). Blackburn (2000) found that group sizes of more than eight become less manageable and small groups can be an advantage if the topic is complex or when dealing with experts (Bloor et al 2001 et al). It is important to choose a group of people that are not too heterogeneous so that participants will be comfortable in sharing their views (Gibbs 1997).

The existing CSIR group consisted of five individuals that knew each other from previous projects. Each of these individuals was contacted personally and asked to participate, and all five agreed but, eventually only three participated.

The typical duration of a focus group can be one to two hours (Gibbs 1997; Robinson 1999) or 75 to 90 minutes (Ouimet et al 2004). The focus group in this study was scheduled for three hours.

Full information on the purpose and objectives of the study must be given to the participants beforehand (Gibbs 1997). It is important that focus group sessions are recorded to facilitate data analysis (Blackburn 2000; Gibbs 1997; Hutt 1979; Ouimet et al 2004 & Robinson 1999) but permission must be obtained from the respondents before doing so (Blackburn (2000). The confidentiality of the participants must also be ensured by not identifying individuals in any publications (Blackburn 2000). The permission of the participants was obtained and the focus group session was recorded.

The focus group was semi-structured: An introduction was given by the moderator, participants were then allowed to discuss the parameters in the study, and a nominal group technique was then used to identify factors. The factors were classified and participants were asked to supply the names and contact details of possible participants for a succeeding Delphi component of the larger study.

The ethical standards of a focus group, in line with the requirements of the University of Pretoria, South Africa were adhered to.

It is important that a facility is selected that is neutral to the group or if a pre-existing group exists, their regular meeting room can be used (Gibbs 1997). The focus group was held in a conference room at the CSIR in Pretoria, South Africa as this was a place familiar to all participants.

Focus groups can consist of pre-existing groups if those groups have the expertise required (Bloor et al 2001:23). Focus groups can vary in size from three to fourteen participants and small groups can be an advantage if the topic is complex or when dealing with experts (Bloor et al 2001:27).

As a pre-existing group existed in the CSIR it was decided to use this group to provide the first inputs for the study.

The nominal group technique was used to identify the most important factors. This technique was used rather than the interacting group technique as according to Delbecq et al (1975) the nominal group technique produces better ideas as it does not inhibit the creative process.

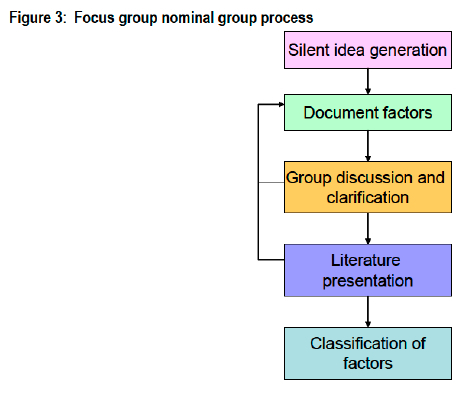

The focus group nominal group process is shown in Figure 3 and was conducted as follows:

Each participant was given six pieces of paper. The participants were then asked to independently write down the six factors which in their opinion was the most important for the selection of renewable energy projects. The participants were asked to work independently and not discuss their ideas.

Before the participants started this task however, the question was raised as to how sustainable energy project are defined. Does it mean that projects will continue after implementation or does it mean that projects will have a triple bottom line, i.e. make a profit, be environmentally friendly, etc.?

Each participant then identified six factors. The pieces of paper where subsequently collected by the moderator. Each factor was then discussed by the group. If what the participant wrote on the piece of paper was not clear it was clarified. Any new factors that came out during the discussion were written down on a new piece of paper and also classified. The factors, a total of eighteen, where pasted on a white board and a preliminary classification of factors was done.

Once all the initial factors had been discussed, participants were given the opportunity to write down independently any other factors that they felt had been overlooked. The same process of discussion, clarification and classification was then followed.

In conclusion, the researcher presented factors which she had identified from the literature. Those factors that had not yet been added and where deemed important by the participants where then added. The focus group produced thirty-eight factors that could be further explored during the Delphi component.

During the identification a preliminary classification of factors was made by pasting the pieces of paper on the whiteboard in different clusters. To classify the factors, some of the clusters where added together. The following final classifications were decided on:

1 Technology factors

2 Social factors

3 Institutional regulatory factors (compliance)

4 Site selection factors

5 Economic/ Financial factors

6 Achievability by the specific organisations

REFLECTION ON APPLYING THE FOCUS GROUP TECHNIQUE

The focus group technique can be successfully applied in research studies were large datasets are not available. The focus group technique must preferably used as one of the inputs to a study where triangulation is applied. It is recommended that the nominal group technique be used during the focus group as the participants then have the opportunity to generate ideas in isolation.

In the example discussed in the paper, the focus group was followed by a Delphi study and during the Delphi study only two new factors, not identified during the focus group, had to be added to the list (Barry et al 2008). This confirms that, especially during the exploratory phase of research, the focus group technique can be successfully used to generate ideas.

In order to ensure the validity of the study it is important that a rigorous process is followed. In particular, the researcher must have a clearly stated problem that the members of the focus group must provide a solution to. It is also important that the problem be clarified to the satisfaction of all the participants at the start of the focus group. It is further important to record the proceedings for later transcription with the permission of the participants. It is recommended that the researcher follows up with the invited participants at regular intervals before the proposed date of the focus group in order to ensure maximum participation.

The use of the nominal group technique and the clustering of ideas are also recommended during the execution of the focus group method.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In conclusion, the focus group technique can be a useful method in the arsenal of the management researcher, as long as the technique is applied with rigour and with the use of triangulation.

The technique can be used in several situations for management research for example during the exploratory phase, between other methods to clarify or confirm results, and at the end of the research to transfer to outcome to the interested parties.

The main requirement to conduct a focus group is at least three geographically co-located experts. It is thus also possible to conduct various focus groups in various geographical areas and then to compare the results.

It is recommended that management researchers carefully evaluate the advantages and disadvantages and the possibility of other methods that can be used for purposes of triangulation before selecting the focus group technique.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BARRY M-L., STEYN, H.S. & BRENT A. 2008. Determining the most important factors for sustainable energy technology selection in Africa: Application of the Delphi Technique. IAMOT 2008 Proceedings. [ Links ]

BLACKBURN R. 2000. Breaking down the barriers: Using focus groups to research small and medium-sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal, 19(1):44-63. [ Links ]

BLOOR M., FRANKLAND J., THOMAS M. & ROBSON K. 2001. Focus Groups in Social Research, Wiltshire: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

DELBECQ A.L., VAN DE VEN A.H. & GUSTAFSON D.H. 1975. Group Techniques for Program Planning: a guide to nominal group and delphi processes. Scott, Foresman and Company, Chapter 4. [ Links ]

GIBBS A. 1997. Focus Groups. Social Research Update, 19:1-7. [ Links ]

HUTT R.W. 1979. The focus group interview: a technique for counselling small business clients. Journal of Small Business Management, 17(1):15-18. [ Links ]

IEA. 2004. World energy outlook 2004. International Energy Agency. Available from http://www.iea.org/textbase/nppdf/free/2004/weo2004.pdf, accessed 19 March 2008. [ Links ]

MORGAN D.L. 1998. The Focus Group Guidebook. New Delhi: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

OUIMET J.A., BUNNAGE J.C., CARINI R.M., KUH G.D. & KENNEDY J. 2004. Using focus groups, expert advice and cognitive interviews to establish the validity of a college student survey. Research in Higher Education, 45(3):233-250. [ Links ]

ROBINSON N. 1999. The use of focus group methodology - with selected examples from sexual health research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29(4):905-913. [ Links ]

SANDURA T.A. & WILLIAMS E.A. 2000. Research methodology in management: Current practices, trends and implications for future research. Academy of Management Journal, 43(6):1248-1264. [ Links ]

UNEA. 2007. Energy for sustainable development: Policy options for Africa [online]. UN-Energy/Africa. Available from http://www.uneca.org/eca_resources/Publications/UNEA-Publication-toCSD15.pdf, accessed 12 March 2008. [ Links ]

UNECA. 2007. Making Africa's Power Sector Sustainable: An Analysis of Power Sector Reforms in Africa. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia:UNESCO. Available from http://www.uneca.org/eca_programmes/nrid/pubs/PowerSectorReport.pdf, accessed 19 March 2008. [ Links ]