Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.6 no.1 Meyerton 2009

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Services science management: the hart beat of the contemporary South Africa enterprise

R Weeks

Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Services is not only the fastest growing sector of the global economy, it in many cases constitutes the major source of revenue for many institutions within business and industry across the world, including South Africa. In the case of South Africa, services represent over 65% of the country's gross domestic product. Seen within this context it is no surprise that services science management has gained the attention of both academics and managers in most developed nations and there increasingly is a growing awareness as to its importance within developing countries as well. It is in effect suggested that it is rapidly becoming the hart beat of many a contemporary South African institution. The purpose of this paper is therefore to shed light on a few of the key issues, in relation to services science management from a South African perspective, by researching and discussing a few pertinent questions, namely:

• The nature of the South African economy and the importance of the services sector to future economic growth;

• The nature of services and the associated management implications thereof;

• The challenges associated with integrating manufacturing and services at a strategic and operational level;

• The need for a new services paradigm of management.

Key phrases: Service science, services economy, T-shaped people, integration of services and manufacturing operations

INTRODUCTION

"South Africa is faced with a unique employment problem: we have high levels of unemployment (estimated at four million job seekers), thousands of high-skill jobs available and approximately 180,000 graduates out of work."

(MacDonald 2005)

As reflected in the introductory quotation, a frequent refrain within the media is the prevailing South African paradox of a very high unemployment rate, while a critical skills shortage exists within business and industry (Weeks 2008b:40). Nowhere is this trend more prevalent, than within the services sector of the South African economy, where it would appear that the skills required are neither clearly understood, nor readily available. MacDonald (2005) captures and clearly articulates this reality in the contention that "because growth is primarily in the services sector (not in mining or manufacturing) many of the unemployed are simply unemployable as they do not have the proficiencies that are in demand". As painful as it truly is for those seeking employment in an emergent services economy, the unemployment situation can really only be more effectively addressed if South African institutions can gain a far greater share of the action within a very turbulent and highly competitive global services economy, as this is the fastest growing sector of the economy globally (Spohrer, Maglio, Bailet & Gruhl 2007; Weeks 2008a:124-125). This in turn implies that the skills required to compete within this sector, needs to be clearly articulated and appropriate skills development initiatives instituted to ensure the availability of these skills.

The Graduate School of Technology Management at the University of Pretoria is one institution that has taken cognizance of the growth of the emergent services sector of the South African economy and is currently in the process of identifying the skills required in this sector from an engineering perspective. In discussions with executives from leading South African engineering orientated institutions, it has become clear that in order to compete in the marketplace they need to offer clients an integrated business solution. From an operational management perspective this entails a merging of manufacturing and services activities. It would appear that this in turn implies the need for a new skills profile that is often referred to as "T shaped people" (Ifm & IBM 2008:19; Weeks 2008c:7). The following statement by Tim Brown (2005) serves as a case in point:

"We look for people who are so inquisitive about the world that they're willing to try to do what you do. We call them "T-shaped people." They have a principal skill that describes the vertical leg of the T - they're mechanical engineers or industrial designers. But they are so empathetic that they can branch out into other skills, such as anthropology, and do them as well. They are able to explore insights from many different perspectives and recognize patterns of behavior that point to a universal human need. That's what you're after at this point - patterns that yield ideas."

It may be indirectly inferred from the quotation that creativity and innovation in gaining an advantage within a highly competitive global marketplace requires a new mindset as well as a multi-disciplinary skills base. Underpinning the mindset change is the development of a services paradigm of management, the traditional paradigm being largely manufacturing biased, thereby limiting the applicability thereof within a services science context (Larsson & Bowen 1999:214; Stuart 1998:470). So for instance the "phenomenon of customers participating in the production of services" (Larsson & Bowen 1999:214) is not readily accommodated within the manufacturing paradigm of management, where the accent is on product standardization and not services customization to meet client needs in the services encounter. It is therefore suggested that the governance and management mechanisms, at the institution and client interface, is inherently different from a services paradigm of management, to that of a product or manufacturing centred mental representation. The reality, however, is that the traditional manufacturing paradigm has become so ingrained in managers thinking and ways of doing things that it is frequently used as a source of reference in an attempt to find solutions for services related operational and management activities. It is contended in this paper that the problem with this is that services are inherently very different in nature from that of manufacturing products. The design of a product manufacturing and a services process consequently has very subtle differences which are not always all that clearly understood and effectively managed in practice. As services increasing become the hart beat of contemporary South African institutions, this implies that the very soul of the institution needs to change in terms of the way managers think and act. The services economy therefore in essence implies a need for a change in the traditional paradigms of management. It is a change that needs to embrace the fact that services operations are inherently different in nature to that of the traditional manufacturing sector of the South African economy.

Strother and Grönfeldt (2005:65) call for a new approach to service management, one that addresses the fear of uncertainty and turmoil that characterizes the global services economy and one where institutions engage its human resources in a quest for gaining a competitive advantage, in a very competitive services marketplace. It is an approach that challenges the service leadership mindset of the entire institution, as it considers every employee-client encounter, or as often termed "moments of truth", to be "an invaluable opportunity to improve customer service and engender customer loyalty' (Strother & Grönfeldt 2005:65). It is in fact stressed by Selden and MacMillan (2006:110) that "it is essential for frontline employees to be at the center of the customer-centric innovation process". The notion of service providers (managers and staff) and the intellectual capital and experience they offer being key ingredients in customized services should not be taken lightly, as they play a critical role in positioning the enterprise in the services marketplace.

Getz and Robinson (2003:130,133) question the traditional innovate or die mantra so often encountered in the literature and suggest that "customer-focused processes and basic continuous improvement play a far more important role than innovation in organizational success". Central to this process, as also suggested by Selden and MacMillan (2006:110), is the role played by client facing staff who are engaged in the services encounters. It is these human enacted moments of truth, supported by appropriate service-centered bossiness processes and technology, which touch the very soul of the services driven enterprise. Leadership in the services centered enterprise is in effect distributed throughout the institution, as each services encounter entails an element of leadership. It is claimed by Strother and Grönfeldt (2005:65) that the concept of "service leadership" is based on a multi-disciplinary approach drawing inter alia on theories of leadership, corporate culture, customer service and human resources management. It is therefore a contention that is in line with the T-shaped people skills paradigm of management.

The skills profile required within a dual services and manufacturing economy is essentially multi-disciplinary in nature. In dealing with the complexity and challenges of having to integrate two fundamentally different services and manufacturing value streams, executives and managers need to be able to assimilate both a traditional scientific paradigm of management with a more flexible and innovative complex adaptive systems approach. They are not mutually exclusive management approaches but in fact are coexistent at any specific point in time and interdependent.

With this brief introductory discussion in mind, the nature of the South African economy and the importance of the services sector for future economic growth are dealt with in the ensuing section.

The nature of the South African economy and the importance of the services sector for future economic growth

In tabling the budget in February this year, I shared an economic weather report with Members of the House, which indicated that there were storm clouds on the horizon ... The storm has arrived, it is fiercer than anyone could have imagined and its course cannot be predicted.

(Trevor Manuel, Interim Budget Speech 2008)

As may be ascertained from the introductory quotation, South Africa's economy is inextricably linked to global economic trends that are not only turbulent in nature but also extremely difficult to predict with any significant degree of certainty. The latest economic meltdown in global markets and the impact on the South African economy is indicative of just how interwoven South Africa's economy is in the fabric of global economic trends and events. Any analysis of the South African economy therefore needs to be undertaken with reference to trends that are emerging on the global horizon, be they storm clouds, a fully blown storm or days of sun shine and prosperity. An important trend in this regard is the shift taking place towards a services driven economy. Within the context of this paper this shift has very specific relevance and the South African trend in this regard needs to be interpreted within the context of this global economic trend. It is suggested in this paper that the emerging trend of a global services driven economy in effect constitutes the very heart beat of many a contemporary South African enterprise.

According to Akosile, (2008) "Some 80 percent of GDP in the US and the EU originates in services. Together they account for over 60 percent of world services exports". Fitzsimmons and Fitzsimmons (2008:3) in a similar sense confirm that the migration to the services economy is without doubt global in nature. Desmet, Van Looy and Van Dierdonck (2003a:7) also confirm that the services is the fastest growing sector of the global economy, but simultaneously claim that the manufacturing and industrial sector in sub-Saharan Africa still plays a very pertinent role in the economy of these countries. Statistics in relation to the services sector of the South African economy are, however, not all that straightforward to analyse, as they tend to be incorporated within various reports with significant exclusions being noted. Some of the services related financial statistics quoted, however, appear to be quite significant. It is suggested that these need to be analysed and interpreted with some care, however, with due regard as to what is included and excluded in the statistics provided. Lehohla (2004:1), the South African Statistician-General, has for instance indicated that the total income for the personal services industry in 2004 was in the region of R107 950 million and clearly this would seem to be a quite substantial amount. It is also of interest to further note that health and social services accounted for no less than 42% of this expenditure and education just over 24% (Lehohla 2004:1). Both these sectors have as of late come under quite extensive criticism within the media and this would seem to suggest that the service delivery cannot be merely evaluated in financial terms. Lehohla's (2004:1) contention that in 2004 there were 426 000 people employed within this sector of the economy is also quite meaningful if seen in the context of South Africa's high rate of unemployment.

The composition of the South African Economy, as cited in the CIA Worldfact book, reflects that the services sector comprises 65.55% of the countries gross domestic product, with industry representing 31.2% and agriculture 3.2% of the GDP respectively (CIA Factbook 2008). Seen within this context it is suggested that the South African economy in effect is a dual services and manufacturing based economy and the two for all practical purposes are inextricably intertwined (Weeks 2008b:124). The South African marketplace is far too small to sustain the economic growth required to address the unemployment situation confronting the country and the South African economy is therefore inextricably linked to the global economy. Global economic trends therefore need to be taken into consideration in any analysis of the South African Economy as they can be expected to be a very pertinent determinant in the South African trade balance.

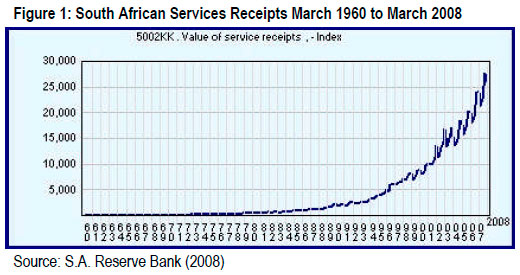

Seen within the context of a transition to a global services driven economy one would expect that services would increasingly feature as a significant sector of the South African economy. It is therefore not surprising that the graph presented in figure 1 reflects a very pertinent increase in the income derived from the services sector of the South African economy. This notwithstanding South Africa's trade balance in goods and services with the rest of the world reflects a very significant negative trend as reflected in the trends depicted in figure 2. Without doubt this is hardly a sustainable situation and South Africa needs to gain a far larger share of a highly competitive global services economy in order to address the increasingly negative trend in the countries balance of payments. Failure to address this negative trend in the trade balance will undoubtedly place the South African economy at risk as any change in international investor confidence, leading to a withdrawal of investments, could have a very significant impact on the country's liquidity. It can therefore be expected that the services sector of the South African economy will in future increasingly gain in relevance and that the trend depicted in figure 1 would need to reflect an even more dramatic increase in order for the balance of payments to regain a far more positive trend.

The role of services in the manufacturing economy can certainly no longer be ignored. Increasingly institutions are not merely providing clients with products, but are in effect providing them with a customized services and products bundle or as frequently terms a complete integrated solution that addressed there specific needs. Within the global marketplace this reality assumes particular relevance in institutions needing to gain a competitive advantage. In many instances the products that are offered are not all that significantly different, but innovation in terms of the services that accompany the products can in effect spell the difference between success and failure. Desmet, Van Dierdonck and Van Looy (2003b:40) cite a 2002 survey among executives from Germany and Belgium, which indicated that "over 90 percent of all manufacturing companies believe that the future development of services is crucial for maintaining and improving their competitive position". This undoubtedly provides support for the need for South African business institutions to view services as a fundamental economic activity that plays a key role gaining a competitive advantage in the global markets.

The South African tourism industry is for all practical purposes services dominant. It brings to the country many thousands of tourists each year who in turn can be expected to purchase crafts and manufactured goods as gifts that they will take back home with them. It is realities such as this that holds the potential for making a difference in turning the negative trend depicted in figure 2 around. As may be determined from this example, services associated with the tourism industry therefore not only generate foreign exchange and employment, but also serves as a catalyst for manufacturing economic activities. The extent to which services and manufacturing have become intertwined within the South African economy can no longer be ignored. The value add potential of services to the South African economy and the balance of payments in particular necessitate a far more in depth analysis of the nature of services and the role it plays in the economy.

With the preceding discussion serving as background, the nature of services and the management implications associated therewith will be briefly dealt with in the ensuing section.

The nature of services and the associated management implications thereof

"Much has been written on what characterises a service and distinguishes it from a product. Basically, one can say that the two basic characteristics of services are intangibility and simultaneity".

(Ronald van Dierdonck 1992:365)

Frequently a system engineering approach tends to be adopted in dealing with manufacturing processes, the accent being on a needs analysis, system design, testing and implementation, with the eventual phasing out of the product at the end of its life span being taken into consideration. It is an approach that has influenced management and manufacturers thinking over many years and it is not surprising that in dealing with the services sector of the economy an attempt has been made to adopt a similar approach. The problem, however, is that as may be seen from the introductory statement services in their very nature are very different to that of products and a manufacturing environment. The manufacturing of products tends to be based on standardisation so as to enable the mass production of the products in question. Services in contrast tend to be customised to meet client needs and expectations that may well differ quite extensively. In addition more often than not clients are inherently involved in the services process themselves, whereas the manufacturing process hardly ever would involve the client. These very different characteristics associated with the manufacturing of products and the rendering of services imply that one needs to differentiate between a traditional manufacturing and a contemporary services orientated paradigm of management. The two paradigms while in certain respects appearing to have aspects that are similar in nature are also in effect very different in many respects. It is these differences that also make services far more difficult to deal with from a management perspective.

A globally integrated network of fibre-optic cable not only gave birth to the internet, it has also given rise to unprecedented opportunities in web based service delivery. Manufacturing operations, however, still tend to be linked to production facilities based at a fixed location, while many services can be rendered across geographical, national and institutional boundaries with relative ease. It is an actuality that has also intensified the competitive nature of the global services economy. Innovation and creativity in meeting client expectations, as well as stimulating a complete new set of client needs, has increasingly characterised the global services economy. A manufacturing system in contrast tends to be far more stable in nature as constant innovative changes have the potential of significantly disrupting the manufacturing process and negatively influence productivity. A manufactured product has both size and a shape and it is very tangible in nature, while services embody a services encounter that is inherently based on relationships that are established, as well as feelings, perceptions and a host of human attributes that are far less tangible. It is nuance differences such as these that contribute to the difficulty of integrating manufacturing and services systems in order to provide clients with a holistic integrated solution that meets their expectations and needs.

Nowhere is the difference between the manufacturing of products and the rendering of services more apparent than in the case of defining what is meant by quality. There are quality standards and bodies established to test products against these standards and provide manufactures with an approval certification. Quality of services rendered is, however, a far more subjective process of comparing the perceived outcome of the service encounter with a prior service expectation. It is without doubt a far more subjective assessment, one were two different people may hold vastly differing views of the exact same service encounter. When personal expectations are exceeded the services rendered are deemed to be of an exceptionally high standard and the converse is equally true in cases where the services encounter did not come up to the prior expectations of the client (Fitzsimmons & Fitzsimmons 2008:108).

Within an extremely competitive global marketplace innovation and creativity in the design and implementation of new services assumes a very definite priority. Yet attempts to patent these ideas and concepts are generally fraught with difficulty, in contrast to being able to patent a new product. It is therefore not surprising that the innovative life span of a service is relatively short before competitors either copy or adapt the service concept to remain relevant in the marketplace. It is the intangible nature of services as opposed to products that manifests itself in attempting to patent a service that complicates the situation. There for instance is not a transfer of ownership, as is the case of physical products that have been manufactured. This begs the question as to what clients are actually buying and paying for. Often it is the reputation of the services provider that plays a key role in determining what can be charged for a service. So for instance lawyers and doctors with an outstanding reputation for the services they deliver will tend to be in demand and in line with supply and demand theory clients will be prepared to pay more for their services. Again we are confronted with the subjective nature of services and the branding thereof.

The bundle of services and the product one acquires from a MacDonalds hamburger outlet and the nature thereof has been established over the space of time and assumes relevance in terms of the branding thereof. The service model associated with MacDonalds in effect has assumed a very specific mental image in the minds of clients and has become interwoven with brand identity. Clients therefore know exactly what they are paying for. This is, however, hardly the case when one goes to a new restraint that has just opened in a specific location. It will need to build an image of service delivery with clients before they will know what to expect. It is this image and its shaping that is not only highly subjective but very difficult to bring into being that adds to the complexity of services management.

The fact that serviced are co-produced with some form of client involvement and as may be inferred from the introductory statement consumed by them simultaneously further tends to differentiate it from manufactured products which can be stored. The ability to manufacture and store products to even out the periodic differences between supply and demand is clearly not an option in the case of services that are consumed with production. A service appointment with a dentist, doctor or lawyer that is not kept by the client results in a revenue loss that cannot be recovered, it is time lost. Managing services capacity therefore assumes far greater emphasis in terms of services than is the case in production of products where inventory can serve as a means for smoothing out of variances in supply and demand. The referred to perishable nature of services as a commodity, such as an unused airline seat or hotel room, implies that services capacity utilisation is a challenge that differentiates itself from the challenges confronting traditional manufacturing operational institutions. As noted this is particularly pertinent in terms of supply and demand fluctuations. Seen in the context of bundled services and product solutions offered to clients it is a management reality that can easily result in client frustrations. While specific products may be available the training of clients in the use of the product or in rendering after sales services may well become an issue of contention. Overzealous sales staff in order to sell a product may promise clients associated services that in practice cannot be delivered in the time available, as a result of services capacity constraints.

The inherent differences in nature between products and services without doubt require a new mindset or way of thinking in the marketing and delivery of the bundled or integrated solutions offered to clients. Frequently, managers who for many years have functioned very effectively in a manufacturing environment, attempt to apply similar processes and thinking in dealing with services. It is precisely here where difficulties are encountered as a result of the very significant differences that exist between services and manufacturing systems. The inherent differences from a systemic and process management perspective need to be taken into consideration in managing value addition and where relevant integration along the value chain. This, however, does not imply that the two need to be seen as separate entities or systems and managed accordingly. The exact opposite is however required, namely a holistic view that takes cognisance of the systemic and process differences that exist. Van Looy et al (2003:41) suggest that management need to break away from a mindset that separates services and manufacturing systems. They go on to stress that instead of attempting to sell products with services as an add-on, the accent and focus should be on the holistic and often customised solution developed for meeting the needs and expectations of clients. In effect it is therefore the total package of services and products with their inherent differences taken into consideration that need to be managed. In the ensuing section the challenges associated therewith will be addressed.

The challenges associated with integrating manufacturing and services at a strategic and operational level

"Modern corporations are increasingly offering fuller market packages or "bundles" of customer-focussed combinations of goods, services, support, self-service, and knowledge. But services are beginning to dominate."

(Vandermerwe and Rada 1988:314)

Vandermerwe and Rada (1988:214) first coined the term "servitization" in a paper published in the European Management journal in 1988 (Neely 2007b). As may be seen from the above quotation from this paper, they appear to have identified an emergent trend, namely one reflecting a need for a services and product bundle, in order to provide clients with an integrated business solution. It is a trend that it would appear has gained in momentum over the space of time. So for instance Professor Andy Neely (2007a) from Cranfied University cites Rolls-Royce and IBM as two institutions that " have reinvented themselves as service businesses, moving away from the production of hardware to offer business solutions". Similarly BP and Shell, both actively engaged in the manufacture of oil related products, are extensively involved in service retail operations. Continuing in this vein Neely (2007b) contends that "Rolls-Royce no longer sells aero engines, it offers a total care package, where customers buy the capability the engines deliver - 'power by the hour". The traditional image of these corporations as manufacturers has as a consequence undergone a fundamental transformation to incorporate a services orientation. In the process the revenue generated from services has in instances exceeded that of the institution s manufacturing operations.

Two fundamental dimensions of management, namely strategy and operations management assume particular relevance with the introduction of the concept "servitization". At a strategic level the very mission or purpose of the organization needs to be reviewed. At an operational level the challenge is one of integrating manufacturing and services systems with due reference to the disparate nature of the two systems concerned, as referred to in the preceding discussion. Also noted in the discussion is the phenomenal growth of service industries and servitization indicating a strategic paradigm shift from mass production to one of post-industrial customized and innovative business solutions. Vandermerwe and Rhada (1988:315) suggest that driving this shift is the need to gain a strategic competitive advantage in a very competitive marketplace. As a result Neely (2007b) concludes for the last decade the "the boundaries between manufacturing and services firms are breaking down across the globe". In formulating strategy this reorientation implies that executives need to redefine what business the institution is engaged in and then develop a servitization strategy to position itself within the marketplace. Increasing institutions are no longer merely in the manufacturing business, but are making the transition to incorporate a services strategy to gain a competitive advantage. This point is driven home by Neely (2007b) in asserting that "to survive in developed economies it is widely assumed that manufacturing firms can rarely remain as pure manufacturing firms. Instead they have to move beyond manufacturing and offer services and solutions, delivered through their products".

Adopting a strategy of servitization of necessity implies a need to integrate product services systems (PSS). Pütz (2008) contends that "changes in the organizational design are to be expected during the transition towards service" orientated operations. Pütz (2008) goes on to claim that "companies need to assure that they can handle the upcoming conflicts and challenges", associated with the transition. It is a reality that impacts on the very heartbeat of the contemporary South African enterprise, as it entails a change in mental perceptions, values, beliefs and above all well entrenched ways of traditionally doing things within the organization. In effect it touches the very soul of the institution, namely its culture and culture transformation is not achieved overnight (Oliva & Kallenberg 2003:166). With this in mind it is not surprising that Oliva and Kallenberg (2003:161) in researching the transition towards a more services oriented operational setting, discovered that "manufacturers' transition into services has been relatively slow and cautious". Brax (2005:143) and Gebauer, Fleisch and Friedli (2005:14) also conclude that the transition to a service focus is generally dealt with on an incremental adaptive or step-wise basis. The challenge of the mindset change involved is well articulated by Oliva and Kallenberg (2003:161) in the following statement that emanates from a respondent interviewed in the course of their research: "It is difficult for an engineer who has designed a multi-million dollar piece of equipment to get excited about a contract worth $10,000 for cleaning it." Yet it may well have been this service add-on that provided the institution with a competitive edge over competitors who were unwilling to take on the maintenance of the equipment after installation.

In a recent discussion with a senior executive from a very large South African manufacturing organization, it was contended that in many instances the sales or front office staff needed the assistance of the engineering personnel to explain and deal with the technological intricacies of the highly complex products manufactured by the institution concerned. The engineering support staff concerned, however, apparently in instances did not have the "people skills" required for turning this customer client interaction into a memorable client orientated experience and as a consequence placed the wrapping up of a very lucrative contract at risk. This anecdote clearly reflects the challenge and need for technical support staff to have gained an understanding of the client services related activities of the institution and the impact thereof on the future survival of the institution in a very competitive marketplace. The transition from product manufacturer into a services provider implies a fundamental mindset change, one from a transaction to a relationship-based business model and as noted by Oliva and Kallenberg (2003:161) the literature in this regards is not all that clear as to how this may be achieved in practice.

The above anecdote brings into question the need for a new skills orientation, that not only embodies the traditional well established technological skills deemed essential for the design and manufacture of products, but one that facilitates the provision and rendering of services on a profitable basis. While still necessitating a need for in-depth technological and manufacturing knowledge, expertise and experience, it is suggested that the breath and scope of the manager's skills base needs to be extended to incorporate the multi-disciplinary skills associated with services management. The skills profile concerned is in line with that previously referred to in the introduction to this paper as "T-shaped people" or adaptive innovators. People with the skills profile required are described as "deep problem solvers with expert thinking skills in their home discipline but also having complex communication skills to interact with specialists from a wide range of disciplines and functional areas" (Ifm & IBM 2008:19).

There is currently a shortage of professional engineers and technologists and those trained in engineering services management are particularly in short supply. The situation can only be expected to be further exasperated with the phenomenal growth of the services sector of the economy on a global basis (Weeks 2008c:7). A key challenge thus facing South Africa institutions, in the process of moving from a predominantly manufacturing orientation to one of offering clients integrated business solutions, is that of acquiring staff with the appropriate skills profile needed and the nurturing of a services centric cultural orientation. The need to build sound relationships with diverse clients and suppliers implies a need for cultural sensitivity at both an executive and operational management level. It is a sensitivity that enables the people concerned to bridge traditional technological (manufacturing) and management (services) mindset differences in dealing with the operational aspects associated with the integration of product service systems. The transition to a bundled approach from a traditional manufacturing orientation and the paradigm change involved will be dealt with more explicitly in the following section of this paper.

In redefining an institution's offering to clients in terms of a bundle of products and customized services it needs to be appreciated that it entails far more than adding layers of services to an existing range of products. The systems that support these operations such as the information systems required need to be put into place as well and staff need to be trained in the use thereof. The service delivery system needs to be blueprinted and the points of interaction and linkage with the manufacturing operations need to be taken into consideration. The services component in effect needs to become more visible at an operational manufacturing level than was traditionally the case. The front office client centred activities need to be aligned to the back office support functions to ensure seamless service and product delivery from a client perspective. In a sense the back office may be seen as being the services factory where service requests are addressed at an operational level. The system integration required is, however, only part of the story, as consideration needs to be given to the design of the servicescapes where client interaction takes place. This is of particular relevance in managing the predominantly manufacturing operations transformation, so as to incorporate service centric components, where there is a tighter and more direct client involvement.

Client's perception of the institution, its products and particularly its services are influenced by their encounters with the institution, often referred to as moments of truth. Increasingly call centres are being used as a means of dealing with client requests for information and services. Each such encounter is a moment of truth during which the client forms an impression of the institution and its operations, dependent on the nature of the service encounter and the clients experience thereof. Servicescapes hold the potential to enhance the client's experience of the service encounter and in certain respects may well influence client behaviour. Spatial layout and functionality of servicescapes create a visual impression of the institution. In addition signs, symbols and artefacts provide glues as to what a client may expects or serve as indicators of what is deemed appropriate behaviour. No smoking signs being a case in point in terms of appropriate behaviour. Servicescape ambient conditions such as lighting, sound, and temperature have a sensory implication that may influence a client's behaviour and service experience. Appropriate attention therefore needs to be given to servicescape design in managing the operational transformation of the institution, as it in a sense constitutes the supporting facility packaging of the services provided. The location of service facilities in relation to manufacturing operations are a further consideration that will need to be considered. The use of electronic systems to interact with clients or web-based service delivery, also assume relevance, as an aspect of consideration in managing the transformation process.

As this very brief discussion suggests, adopting a product service bundle approach in meeting client needs, is far more complex than just adding an additional services layer to existing products offered to clients. It entails a significant transformation in terms of the physical servicescapes required, their location, design and layout as well as operations. It in effect necessitates a cultural reorientation in terms of the way things have traditionally been done within the institution. An extensive analysis of all the factors that need to be considered in managing the transition and systems integration cannot be effectively dealt with in a paper such as this. The purpose here being to but to create an awareness of the complexities involved in bundling services and products offered to clients and the intricacies associated therewith. In the following section we will deal more specifically with the underpinning mindset changes that are required.

The need for a new services paradigm of management.

"In the 'managing knowledge' marketplace, there is little evidence of much diffusion of ideas, innovative business models, or management practices. In organizations not implementing what they know they should be doing based on experience and insight, and in companies not acting on the basis of the best available evidence, one factor explains the difficulties - the mental models or mind-sets of senior leaders."

(Jeffrey Pfeffer 2005:123)

A central and important tenet in managing the transition to a services centric business orientation is the need to instill a new service directed paradigm in the hearts and minds of all staff members. Pfeffer's (2005:123) introductory quotation attests to the fact that the mindsets of institutional leaders remain a stumbling block in managing the transition. The predominant manufacturing paradigm of management, based on rational analytical and scientific thinking, has its genesis in many decades of traditional management practice and in effect constitutes the very heart beat of many South African institutions. It is therefore not surprising to find that in attempting to implement service systems, processes and practices managers tend to adapt or make use of some form of traditional manufacturing systems thinking. This notwithstanding the fact that, as seen in the preceding discussion, services tends to have very different characteristics that make such an approach far less viable in practice and in certain respects impractical. The associated service management transition rhetoric tends to reflect contemporary clichés that emphasize staff empowerment, the need for innovation, teamwork, client centric thinking and similar truisms, but as noted by Pfeffer (2005:123) they are frequently still not implementing the very changes they inherently know are required. Baines et al (2007:1549) claim that the adoption of integrated product service systems solutions, in contrast to additional services being merely added to product offerings, entails a cultural shift with an associated inherent mindset change that breaks down the "business as usual attitude" that prevails within the institution. The specific systemic changes are relatively straightforward to introduce but the difficulty so often encountered relates to the changing of the underpinning philosophy of how services centric business operations are conducted (Pfeffer 2005:124). It is a socio-cultural transformation that focuses far more on establishing and maintaining sound relationships between clients and the institution, than on just satisfying client needs through core business activities. The difference is rather subtle in nature, but yet vital, as it involves the way staff will interact with clients in co-producing the product services bundle required by clients (Vandermerwe & Rada 1988:318). Implied is the notion that "value is created collaboratively in interactive configurations of mutual exchange" which places an accent on the relationship and behavioural aspects involved in the services encounter (Vargo, Maligo & Akaka 2008:145).

The golden tread that runs through the transition to a services dominant logic at an operational level is one of engendering a fundamental mindset change in how staff view the activities of the organization and their role therein. The dominant manufacturing systems paradigm is one in which institutions are engineered to function as an integrated system to meet client needs in terms of products, while the interaction and relationships between people assumes far greater relevance relevance in adopting a services centric business approach. Clearly it is the human elements involved in relationship building and interaction that distinguish the services paradigm from the traditional systemic based paradigms of the manufacturing era. The logic and rationality underpinning the manufacturing systems paradigm may in instances not always be all that applicable in a services context as people do not always act rationally when their emotions influence their decision making processes. Context also comes into play, as what is deemed to be rational behaviour may in effect differ in different contexts and circumstances.

Within the services related management literature a frequent theme encountered is that of quality and total ownership costs associated with the purchase of a product. This stands in contrast to a services dominant paradigm where the accent is on ensuring that the client's total encounter with the institution and its activities is one that will enhance the establishment of an enduring mutual relationship. Issues such as trust, that inherently incorporates an emotional element in the establishment of relationships, and the active role played by clients in the services process are important factors of consideration in managing services operations (Baines et al 2007:1549; Ordanini & Pasini 2008:26; Vargo et al 2008:146). The quality of the service encounter by implication is to a degree shaped by and dependent on the client's actions, behaviour and attitude as well. Rarely do clients get involved with manufacturing of the product they intend to purchase and consequently clients themselves are subjected to a paradigm change when it comes to services. If clients provide inaccurate information, vague or ambiguous service requests, the quality of the services may be significantly affected. Management thinking based on a product dominant mindset may therefore no longer be consistent with the realities associated with services related management practice, where the client assumes a pertinent role as a co-producer of the service. The traditional product based business model assumes institutional control of the production systems and therefore of the decision making activities in relation thereto. It is an assumption that is challenged by the services business model in terms of the role played by clients in the decision making processes. Customization of services in terms of the specific needs of clients is an example of the changing business model. It is no longer a case of mass production with efficiency and quality as the central focus; it is a case of customizing a service and product bundle to secure a value proposition that will meet the specific needs of clients on a profitable basis.

In the highly competitive global services marketplace the extended enterprise is increasingly becoming a reality. Aspects of the institution's operational activities could well be outsourced and this by implication means that dyadic relationships are making way for team collaboration that involves clients as active participants. Collaboration based relationships become far more complex as the number of people, institutions or entities involved in the value chain increase and the traditional business model needs to make way for new ways of conducting business at a strategic and operational level. Integrating entities with diverse values, beliefs, expectations, and perceptions, into a team able to meet diverse client product and associated services needs inherently implies a change of management paradigm. It is a paradigm that needs to engender sensitivity for dealing with socio-cultural diversity. As business activities across geographical boundaries increase the need for such sensitivity and an understanding of the nature of this diversity becomes even more imperative. The picture that emerges is one where a services dominant logic is rapidly changing the traditional landscape of the business environment and consequently engendering a need for new paradigms of management. The question thus is one determining the nature of this new paradigm. Underpinning its nature is a new holistic services and products value configuration. It is one that embodies and supports diversity and is certainly inclusive in character. The paradigm is service centric in nature and places clients and their specific needs at the epicenter of its focus. Without doubt is one that embraces innovation and renewal as a fact of life.

The global services economy is characterized as being subject to unexpected and unforeseen events that have a tendency to significantly change the business landscape. Some form of predictability has certainly been traditionally assumed in formulating strategy and developing an institution's business plans. As has been reflected in so many recent instances, such as the current economic meltdown in world markets, it is an assumption that has been found to be very questionable. The reality it would appear is far more one of unexpected and dramatic events taking place that gives rise to new emergent patterns that reshape the business landscape. The new paradigm of management therefore needs to embrace complexity and the need to be able to identify and rapidly respond to the new emergent patterns as they arise. It suggests that institutional resiliency needs to be nurtured to enable institutions to survive in a global services economy that is characterized by instability. Central to such resiliency is the mental models that are instilled with the hearts and minds of all the institution's employees. It is suggested that at the very core of these models is a value system that all employees can embrace without reservation and live out in their day-to-day activities directed at realizing client needs and expectations. They in effect need to constitute the very heart beat of the contemporary South African enterprise. It is a heartbeat that needs to beat in synchronism with a very dynamic and evolving global services economy.

With the preceding discussion in mind it is suggested that South African institutions need to ensure that they do not get engulfed and caught-up in mindsets that are more appropriate for a predominantly manufacturing era, when the trend is clearly one of moving towards a very dynamic and innovative services dominant economy. As noted by Pfeffer (2005:125) "most of our models of business and behaviour are unconscious and implicit", which suggests that the first step that needs to be taken is one of getting both managers and staff to reevaluate how effective their existing implicit mental models are for gaining a competitive edge in what constitutes a global services marketplace. It implies that many traditional management practices, business models and ways of doing things will need to make way a new paradigm of management that is more in line with a services dominant economy. Changing the way people think and act is certainly no easy task, as people become quite comfortable in their well established comfort zones of traditional management practice. Pfeffer (2005:125) confirms that "changing how people think is going to be more difficult than just changing what they do, since assumptions and mind-sets are often deeply embedded below the surface of conscious thought". This notwithstanding it is stressed that if South Africa is to nurture a future generation of T-shaped people with the skills and mindsets required for effectively functioning in the services economy, the firsts step needs to be taken. "In spite of the apparent difficulty and its less tangible nature, changing the way people think about situations is, in fact, the most powerful and useful way to ultimately change behaviour" (Pfeffer 2005:125) and thereby enhance institutional resiliency in dealing with the transition to a services dominant economy.

Concluding comments

The growth of the services sector of the South African economy has been quite phenomenal and reflects global trends in this regard. It raises the question if South African institutions have managers and staff with the appropriate skills profile and mental models required for effectively realigning the institutions concerned to meet the challenges associated with a services dominant economy. It is suggested that far more extensive empirical research is required to effectively find an answer this question. The purpose of this paper, however, was not to find an answer to this question, but one of shedding light on a few of the key issues, in relation to services science management from a South African perspective. In so doing it is hoped that the way will be paved for future more in depth research as to how best to position South African institutions to meet the challenges associated with a dual services and manufacturing economy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AKOSILE A. 2008. Africa: World Bank Seeks Faster Integration of Services Markets. [Online] Available Url: http://allafrica.com/stories/200802060519.html [Downloaded: 07/02/2008]. [ Links ]

BAINES T.S., LIGHTFOOT H.W., EVANS S., NEELY A., GREENOUGH R., PEPPARD J., ROY R., SHEHAB E., BRAGANZA A., TIWARI A., ALCOCK J.R., ANGUS J.P., BASTL M., COUSENS A., IRVING P., JOHNSON M., KINGSTON J., LOCKETT H., MARTINEZ V., MICHELE P., TRANFIELD D., WALTON IM. & WILSON H. 2007. State-of-the-art in product-service systems. IMechE, 221:1543-1552. [Online] Available Url: http://www.producao.ufrgs.br/arquivos/disciplinas/187_exemplo_artigo_revisao_estado_da_arte_pss.pdf (Downloaded 3 January 2009). [ Links ]

BRAX S. 2005. A manufacturer becoming services provider - challenges and a paradox. Managing service quality, 15(2):142-155. [ Links ]

BROWN T. 2005. Strategy by design. [Online] Available Url: http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/95/design-strategy.html?page=0%2C1 (Accessed 12 August, 2008). [ Links ]

CIA WORLD FACTBOOK. 2008. South Africa. [Online] Available Url: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sf.html [Downloaded: 07/02/2008]. [ Links ]

DESMET S., VAN DIERDONCK R. & VAN LOOY B. 2003a, The nature of services. In Van Looy, B., Gemmel, P., Van Dierdonck, R. (Eds),Services Management: An Integrated Approach, Pearson Education, Harlow. [ Links ]

DESMET S., VAN DIERDONCK R. & VAN LOOY B. 2003b, Servitization: or why services management is relevant for manufacturing environments. in Van Looy, B., Gemmel, P., Van Dierdonck, R. (Eds),Services Management: An Integrated Approach, Pearson Education, Harlow. [ Links ]

FITZSIMMONS J.A. & FITZSIMMONS M.J. 2008. Services management: Operations, strategy, information technology. London: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

GEBAUER H., FLEISCH E. & FRIEDLI T. 2005. Overcoming the services paradox in manufacturing companies. European management journal, 23(1):14-26, February. [ Links ]

GETZ I. & ROBINSON A.G. 2003, Innovation or die: is that a fact? Creativity and Innovation Management, 12(3):130-136, Sept. [ Links ]

IfM AND IBM. 2008. Succeeding through Service Innovation: A Service Perspective for Education, Research, Business and Government. Cambridge, United Kingdom: University of Cambridge Institute for Manufacturing. [ Links ]

LARSSON R. & BOWEN D.E. 1999. Organization and customer: managing design and coordination of services. Academy of Management Review, 14(2):213-233. [ Links ]

LEHOHLA P.J. 2004. Personal services industry 2004. Statistics South Africa. [Online] Available Url: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P9001/P90012004.pdf (Accessed 2 November 2008). [ Links ]

MACDONALD I. 2005. High unemployment and myriad job vacancies: A South African paradox. [Online] Available Url: http://www.sagoodnews.co.za/newsletter_archive/high_unemployment_and_myriad_job_vacancies_a_south_african_paradox.html (Accessed 12 November, 2008). [ Links ]

MANUEL T. 2008. Medium Term Budget Policy Statement 2008. [Online] Available Url: http://www.finance.gov.za/documents/mtbps/2008/mtbps/speech.pdf (Accessed 4 December 2008). [ Links ]

NEELY A. 2007a. The servitization of manufacturing. [Online] Available Url: http://www.cranfield.ac.uk/sas/pdf/servitization.pdf (Accessed 5 December 2008). [ Links ]

NEELY A. 2007b. The servitization of manufacturing: an analysis of global trends, 14th European Operations Management Association Conference, Ankara, Turkey. [ Links ]

OLIVA R. & KALLENBERG R. 2003. Managing the transition from products to services. International journal of service industry management, 14(2):160-172. [ Links ]

ORDANINI A. & PASINI P. 2008. Service co-production and value co-creation: The case for a service-oriented architecture (SOA). European management journal, 26(5):289-297. [ Links ]

PFEFFER J. 2005. Changing mental models: HR's most important task. Human resources management, 44(2):123-128, Summer. [ Links ]

PÜTZ F. 2008. Transformation to service: When organizational structures limit your service success! Presentation at the Frontiers in service conference, 2008. [Online] Available Url: http://www.rhsmith.umd.edu/frontiers2008/pdfs_docs/Puetz.pdf (Accessed 2 December, 2008). [ Links ]

SELDEN L. & MACMILLAN I.C. 2006. Manage customer-centric innovation systematically. Harvard Business Review, 84(4):108-116, April. [ Links ]

S.A. RESERVE BANK. 2008. 5002KK. Value of service receipts, - Index (MAR-1960 - MAR-2008). [Online] Available Url: http://www.thedti.gov.za/econdb/raportt/ra5002KK.html (Accessed 2 December, 2008). [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY. 2008. Balance of payments: South Africa Mar-2008. [Online] Available Url: http://www.thedti.gov.za/econdb/raportt/BalPay.html#Balance%20of%20Payments (Accessed 2 December 2008). [ Links ]

SPOHRER J., MAGLIO P.P., BAILEY J. & GRUHL D. 2007. Steps toward a science of service systems. IEEE Computer Society, 40(1):71-77. [ Links ]

STROTHER J.B. & GRÖNFELDT S. 2005. Service leadership: the challenge of developing a new paradigm. Professional Communication Conference, 2005. IPCC 2005. Proceedings. International, 10(13):65-71, July. [ Links ]

STUART F.I. 1998. The influence of organizational culture and internal politics on new service design and introduction. International journal of service industry management, 9(5):469-485. [ Links ]

VANDERMERWE S. & RADA J. 1988 Servitization of business: adding value by adding services. European Management Journal, 6(4):314-324. [ Links ]

VAN DIERDONCK R. 1992. Success strategies in a services economy. European management journal, 10(3):365-373, September. [ Links ]

VARGO S.L., MAGLIO P.P. & AKAKA M.A. 2008. On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. European management journal, 26(3)145-152, June. [ Links ]

WEEKS R. 2008(a). The services economy: A South African perspective. Management Today, 24(1):40-45, February. [ Links ]

WEEKS R. 2008(b). Nurturing a culture and climate of resilience to navigate the whitewaters of the South African dual economy. Journal of Contemporary Management, 5:123-136. [ Links ]

WEEKS R. 2008(c). The dawning of a new era of management in South Africa. INCOSE Newsletter, 23:6-8, October. [Online] Available Url: http://www.incose.org.za/downloads/INCOSE%20SA%20Newsletter%20Q3%202008.pdf (Downloaded 10 December 2008). [ Links ]