Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.5 n.1 Meyerton 2008

RESEARCH ARTICLES

The protestant ethic and its' effect on the study of management

GA Goldman; TN van der Linde

Department of Business Management, University of Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

This speculative, self reflective paper looks at the inculcation of the protestant ethic through western civilisation and how it has become part of the moral fibre of capitalism and "doing business". But this inculcation is not without its pitfalls. It has also caused us, as academics, to become lost in the malaise of mundane research efforts. We try to show that we are caught up in the shadows on Plato's "wall of the cave" as far as the study of management is concerned; that the very capitalist (and accompanying protestant) tradition that our western economic society is based on is hampering our perceptions of what constitutes reality

Key phrases: Reformation of the Church; capitalist spirit; protestant ethic; Plato's Cave; management research

INTRODUCTION

We would like to put our thoughts - based on empirical experience - down on paper without having to test a hypothesis or prove the causality of a relationship between two variables. We are grappling to come to terms with exactly how research within the ambit of the Management Sciences should be approached. We are at loggerheads with the rigidity of the South African academic community (relating to the Management Sciences) in terms of their stringent Positivist stance toward research. As pragmatists, we argue that the study of Management has to be conducted from an ontology of multiple realities; and that the Phenomenological notion of intersubjectivity is vital to meaningful interpretation in the Management Sciences.

However, it has become apparent that meaningful research in the Management Sciences is dependant on a sound understanding of the philosophical tenets underscoring Management as a scientific discipline. In the South African context, it is alarming to note that this philosophy seems to have been forgotten. Our vision is thus to revitalise an appreciation for the philosophy of Management as a science.

Against this backdrop, we also need to look at the impact of historical events on the philosophy, study and practice of management. One such event concerns a revolution in the moral fibre of western society: the reformation of the church. Though rooted in broad dissatisfaction with the Church, the reformation is traced back to the protests of Martin Luther (1483 - 1546) (Wren 2005). Luther nailed a 95 point manifesto to a church door in Wittenburg, Saxony in 1517. Fundamental to this manifesto was a basic questioning of the tenets of the Roman Catholic Church, including the right of individual clergy to grant salvation. For Luther, human salvation depended on the faith of the individual (Gregersen 2006). The Bible was thus seen to be the ultimate and sole source of Christian truth (Wisse 2002).

The reformation initiated by Luther had more far reaching implications than merely the founding of Protestant Christian churches, it saw an end to the Catholic churches' dominance of society in Europe. The protestant movement initiated by Luther spread quickly and grew in popularity. Particularly northern Europe embraced the new Protestant movement, although reaction to the Lutherian protests differed from country to country. In Particular, John Calvin, with his work The Institutes of the Christian Religion, codified the doctrine of the Protestant faith; which would later form the basis of Presbyterianism (Wisse 2002).

During the middle ages, the Catholic church, apart from dominating society at almost every level, provided the hope of the afterlife as a consolation for the current life; an end goal that could only be achieved through piety, subsistence and salvation; an anti-materialistic philosophy that viewed trade and business as an evil necessity. The Reformation saw the inculcation of a protestant ethic permeating through Europe. This ethic was typified by living a life that was meaningful in the eyes of God. Salvation, therefore, could only be achieved through labour for the glorification of God. Self-interest was thus promoted, as it resulted in surplus which could be distributed amongst those who needed it most; with redistribution in itself being a task in the name of God. Trade and business were thus not frowned upon, but viewed as essential to promote this protestant ethic (Wren 2005).

MAX WEBER, RICHARD TAWNEY AND THE PROTESTANT ETHIC

The German sociologist and political philosopher, Max Weber, was interested by a seeming relationship between the rise of Capitalism and the spread of (especially) Calvanistic Protestantism (Wren 2005). For Weber, a causal relationship existed between the two in that Capitalism seems to have flourished in areas where Calvanistic Protestantism dominated (Delacroix & Nielsen 2001; Westby 2007). This he puts forward in 1958 in his work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which has been widely defended as well as criticized (Delacroix & Nielsen 2001; Haralambos & Holborn 2004).

Weber held that a remote and unknowable God, together with the central Calvinistic tenet of predestination, created intense anxieties within individuals regarding their state of grace (Gregersen 2006; Westby 2007; Wren 2005). Practically, these anxieties could be reduced by commitment to a calling. In other words, hard work, discipline and thrift became the Protestant means of living a good and fulfilled life in the eyes of God (Delacroix & Nielsen 2001). This calling to hard word lead to material reward, which were not consumed personally, but were saved up, redistributed and reinvested (Haralambos & Holborn 2004; Westby 2007).

It is interesting to note that the English historian, Richard H Tawney (in his work Religion and the Rise of Capitalism) basically agrees with Weber, however Tawney argues that the relationship between Capitalism and Protestantism is not necessarily cuasal; and also places less emphasis in his work on Calvinism, but makes the argument effective to Protestantism as a whole (Westby 2007). For Tawney, Capitalism evolved along with Protestantism, and not because of it, as put forward by Weber.

Tawney purports that centers of commercialism rose before the Reformation. However, the emergent middle class that resulted from these centers tended to gravitate toward the new protestant sects, due - primarily - to the fact that the established churches (Anglican and Roman Catholic) were closely alligned to the landholding aristocracy (Westby 2007).

Although the works of Tawney and Weber have endured much criticism, the aim of this discussion is to present the basic stance of the protestant ethic; which is to be devout to a distinct calling typified by hard work, thrift and self discipline. This calling also ascetic, implying abstinence from life's pleasures, an austere lifestyle and -again - self discipline. The accumulation of wealth is seen as a measure of success to one's calling, which implies that the individual has not lost grace in the sight of God (Haralambos & Holborn 2004). This is a marked turn from pre-Reformation Catholisism, where salvation can only be granted through a life of piety and repentance (Wren 2005).

It serves no purpose in this discussion to argue whether the stance of Weber or Tawney is the more correct one. The basis of the argument is that the protestant ethic is present and shows marked similarity and alignment with capitalist doctrine, where the pursuit of profit and forever renewed profit is central. Weber and Tawney do, however, prove that capitalist thinking and religious (in this case Protestant) doctrine have common traits, which could (and as argued by Tawney and Weber, do) result in an affiliation between the two.

In concluding this section it would be prudent to also introduce the work of Werner Sombart. Sombart was a German sociologist who, just as Weber and Tawney did, attempted to establish a relationship between modern economic society - and capitalism in particular - and civil society. However, whereas Weber and Tawney found a relationship between capitalism and Protestantism, Sombart sought to establish a link between capitalism and the Jews in his work The Jews and Modern Capitalism (Loader 2001). For Sombart, there was a direct link between the geographical displacement of Jewish people throughout Europe - especially northern Europe - and the rise of capitalism in these European countries (Loader 2001). Sombart also drew parallels between Jewish culture and capitalist spirit, including contractual and legally regulated relationships, a system of bookkeeping a concern with profit and an ascetic attitude toward worldly pleasures (Loader 2001)

Sombart's work provides an interesting alternative to that of Tawney and - in particular - Weber. But the work of Sombart has been - and somewhat unjustly -coupled to anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda. The largest criticism of Sombart's work, however, was the use of many unfounded an non-authoritative sources that his work was based on (Loader 2001); which implies that Sombart's work, however interesting and thought provoking, cannot be used as a juxtaposition to the Work of Weber and Tawney, in our view.

BUSINESS MANAGEMENT AND BUSINESS MANAGEMENT RESEARCH

The essence of the preceding discussion indicates, then, that the overriding effect of the protestant ethic is not only to work harder, systematic and continuous to obtain wealth; but that this wealth is an indication of God's blessing (Weber 2002) that will testify to the believer's "elect" status. But what does this "systematic and continuous work" and "elect status" imply for the study of management - and more particularly -for the creation of "wealth"?

Irrespective of your discipline, academic background or the economic model you are exposed to - business management strives to align and direct resources through a transformation process to achieve a value created output at the end. This value or wealth, created through the protestant ethos, is the overriding deliverable of the CEO (Weymes 2004). This wealth creation has been institutionalised by Taylor as "the scientific approach to management". Corporate scandals - and for that matter "management scandals" - consistently require a new approach to management. After each corporate scandal new voices ask for a new management model; and for each "new model" researchers develop the "capitalist spirit becomes further entrenched through research. This notion is echoed by Taleb (2008:45) who is uncompromising in his statement that:

"We like business models because they do not require experience and can be taught by a 33 year old assistant professor".

This "scientific approach" to management also laid the foundation for scientific management research through "careful study and analysis". And as organisations become more numbers driven, managers and researchers are designing new processes and systems (based on the careful study and analysis of the elect few that have achieved their numbers) to control the business environment. At the foundation of these "antiquated" management theories, processes and systems lies the philosophy that underpin business management. This philosophy needs to be questioned by researchers, theorists and management practitioners.

PLATO'S CAVE AND BUSINESS MANAGEMENT RESEARCH

To indicate the dilemma that business research finds itself in, we would like to make liberal use of Plato's allegory of the cave (Figure 1). Plato used this allegory as point of departure in his search for understanding and true knowledge. Weymes (2004) also draws his discussion about the challenges to traditional management back to the era of Plato and Aristotle

We as academics, theorists, researchers and managers find ourselves isolated in an antiquated world when viewing the management sciences. This world can be compared to Plato's cave; where we are all prisoners chained to chairs (theories, processes and systems) through our protestant ethos. We observe our businesses in front of us as shadows on the cave wall. Some of these shadows are very clearly defined (financial statements) and others blurred (strategic management), but we all observe and understand these images in exactly the same manner. Why? Because we are all educated by business schools (formed by and based on the protestant ethos) that offer the same curriculum content (Semler 2003).

This further entrenches the protestant ethos that we can become part of the elect, by doing the same as they do, just better and faster. But when one of us "escapes" from his imprisoned position and notices that the shadows are mere images of cut-outs being reflected on the cave wall by a light source (fire) at the back of the cave, we -as the escaped prisoner - can identify the objects that the cut-outs are based on outside the cave. With tools to our disposal, (scientific research and business models) we can create more vivid images (... research has indicated ....), or even new ones that are even more vivid to the other prisoners still trapped in the cave

The moment this clearer image, or phenomenon, (especially in business management and related disciplines) comes under the attention of researchers, academics and managers, the escaped prisoner that sharpened the image will achieve the "elect status" of a management guru. This glorification is normally also fuelled by the popular press. But the fact of the matter is that nothing new has been produced. This elect "guru" has actually re-entered the cave. He/she is entrapped, not only by his/her protestant ethos, but also by all the other chains that he/she has themselves entwined in, in the act of creating the more vividly defined images that have been re-introduced into the cave.

Consider for a moment SEMCO and its unique way of managing a business. Breaking free from his cave, and therefore "conventional wisdom", Semler reinvented - for SEMCO - just what it means to lead a business. This, in turn, lead to new, more vivid images being produced in terms of how a business should be managed. Some of the new images and objects that Semler and company (Semler 2003) created were, for example, getting rid of the HR function (although not the activities), introducing an organisational structure without a CEO (or President), getting rid of a five year budget (in place to enhance control, cf. Mintzberg 1994). These phenomena became so important that, according to Semler himself, SEMCO became required reading at 271 business schools and 16 post graduate students (Master's and Doctoral candidates) have made SEMCO the subject of their research. (Semler 2003:12). Semler himself achieved such an "elect status" that he was addressing over 300 workshops and conferences (Semler 2003).

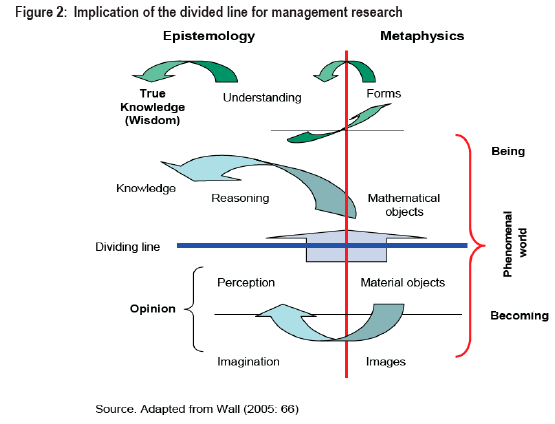

At this moment we should also introduce divided line analogy of Plato (Figure 2) to demonstrate the level of this "new knowledge" or sharpened image. Through our imprisonment in the cave we observe phenomena; the images and material objects (shadows and cut outs), and through our imagination and perceptions we turn these images and material objects into an opinion.

This opinion is then reworked into curriculum we teach and research findings we generate. Through the application of supposed "reasoning" (limited by the traditional scientific methods), we endeavour to understand the mathematical objects we have constructed (business models). But these business models are mere notions based on the shadows of material objects we observe reflected on the back of the cave wall. To give credence to our "new" knowledge we design custom words to support it; such as entrepreneurship, stakeholder involvement, corporate social responsibility, enterprise risk management, corporate footprint, clean fuel and others. This is nothing more than creating labels for these new, more vivid cut outs to keep the prisoners further mesmerised in their view or perception of reality.

For Plato, crossing the line from reasoning to understanding very seldom happens. For us as management researchers, this can only happen once we as researchers (not excluding academics and managers) are prepared to cannibalise our existing knowledge. To even consider (before we admit) that the phenomena that we observe may only hold true for a specific moment in time and cannot be generalised, is an option that merely does not exist for many researchers. We need to be prepared to escape totally from the cave and be exposed to the sun and not the light source in the cave, to search for the underlying, true knowledge (wisdom) and not only knowledge as it appears in the sensory world.

The philosophical argument presented above holds consequences for both management research and management practice. The fundamental question in this period of world business and economic turmoil (i.e. where we are now; in the year 2008) should be: "How do we go forward in business research, or will we forever be describing these copied phenomena in detail and call it lessons learnt?" How will business researchers and practitioners respond and recover from these phenomena that are so deeply entrenched in their minds (the images in the cave); how strongly has our protestant ethics kept us chained to the chairs in the cave, or can we, somehow, break these shackles and escape from the cave into the world of the sun, true wisdom and real new knowledge?

RESEARCH CONSEQUENCES

The unfortunate reality for us as researchers is that we will keep on focusing more on the sensory aspects of management; that which is reality - or which appears to us as reality at a specific moment in time. We will describe, we will postulate, we will hypothesize; but this keeps us trapped in the cave. In general most of us will not endeavour to go out into the sun and gain true knowledge through understanding. Those of us who show the courage to cannibalise our knowledge, to escape the cave in search for true knowledge very seldom return to the cave. As academics, we are "put to death" (i.e. stifled in our thinking) through reviewers and review processes that are still caught up inside Plato's cave. Thus, we withdraw to an environment where we can practise our new found "true" knowledge. Through this, we can move closer to Plato's "true knowledge", implying an alignment with our true purpose in life; thereby giving expression to the Calvinistic notion of the salvation of the "select few" that have answered their calling.

Has the protestant ethic that flows through capitalist society also found its way in the way we as academics (and business management scholars in particular) conduct our research? Publish or perish. To attain your calling as an academic you need to have a long list of publications. This implies self-discipline, hard work and thrift. The reward is a professorship and knowledge we can plough back into the minds of our students. But how many of us are willing to break with this convention; to challenge journals and conference organisers until we are given a platform; not to conform to critique from peer reviewers until we meet the set criteria?

We have a basic ontological stance concerning our subject fields, yes. But what constitutes "reality' as far as conducting research is concerned; what constitutes "real" research? Is it formulating a hypothesis based on heaps of preceding literature and findings of other scholars; developing a questionnaire; collating the data; subjecting it to a statistical intervention and interpreting the results just to find what so many have found before? Or is it asking questions about how the very fibre of reality is constituted. Maybe we need to start asking the right questions - as Kant rightly pointed out - before we can find answers (Wall 2005). And maybe B-rate, 1960's sci-fi shows have more truth than we would like to give them credit for. After all, as Captain James T Kirk said "To boldly go where no man has gone before." Maybe we have lost the courage to do this.

BUSINESS MANAGEMENT CONSEQUENCES

For business the impact of research is that we as researchers will create so much more of the same, more sharpening of the cut-outs, more new cut-outs - in that all businesses will be managed more the same. Is this a requirement to control our uncertainty about tomorrow - that all businesses looks the same, or are we as researchers prepared to cannibalise our knowledge? That our reasoning to support the metaphysical world of material and mathematical objects is transformed and we became exposed to the sun and gain true knowledge. That each business is unique in its own, has its own DNA and that the prisoners are freed to enjoy the sun (true knowledge) themselves. By adopting a new management philosophy, business management will have to cannibalise their existing knowledge. A painful realisation that our business models don't hold true anymore.

CONCLUSION

Researchers are attempting to implement their new "observations, study and analysis", but are unwilling to give up the (scientific) methodologies associated with established management theories. Rigid adherence to prescribed research methodologies will no longer guarantee the creation of useful - new knowledge required in a wisdom economy. Researchers and managers must pay as much attention to the context in which they do research and not only the content, and the impact of their research on the wisdom economy.

The focus of business research must change so that the researcher in the business management research domain must truly control the research process, not by careful study and analysis of existing knowledge, processes and systems; but generating true knowledge for a wisdom economy; a new research process where successful, sustainable business research are founded in truth and wisdom creation.

This is an earnest dialogue in its quest for a change in business management research. We as researchers and managers need to transform our business management environment from a knowledge economy to a wisdom economy. In this wisdom economy new management models should be based on a new management philosophy. Moving away from being one of the "me too" and the "elect few", to a protestant ethos of being an instrument in God's hand to transform the world to the good of all man. From a research environment where we not only explain the phenomena we observed in the sensory world, but cannibalising our knowledge to create wisdom (true knowledge) instead. Moving away from the sensory to the true meaning; the "real real", as Plato put it; where we understand the true consequences of our research, long after the implementation of our findings and recommendations.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DELACROIX J. & NIELSEN F. 2001. The Beloved Myth: Protestantism and the Rise of Industrial Capitalism in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Social Forces, December 2001, 80(2):509-553. [ Links ]

GREGERSEN N.H. 2006. Beyond Secularist Supersessionism: Risk, Religion and Technology. Ecotheology, 11.2:137-158. [ Links ]

HARALAMBOS M. & HOLBORN M. 2004. Sociology: Themes and Perspectives. Collins: London. [ Links ]

LOADER C. 2001. Werner Sombart's "The Jews and modern Capitalism". Society. Nov/Dec:71-76. [ Links ]

MINTZBERG H. 1994. The rise and fall of strategic planning. Prentice Hall Financial Times: London. [ Links ]

SEMLER R. 2003. The seven day weekend: A better way to work in the 21st century. Arrow books: London. [ Links ]

TALEB N. 2008. Fear of a black swan. Fortune. Europe edition. April 14, 15(7). [ Links ]

WALL T.F. 2005. On human nature. An introduction to philosophy. Thomson Wadworth: Belmont. [ Links ]

WEBER M. 2002. The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. New translation and introduction by Stephen Kalberg. Blackwell publishing: Los Angeles. [ Links ]

WESTBY D. 2007. Protestant Ethic. Available from: http://mb-soft.com/believe/txn/protesta.htm (Accessed 27 March 2008). [ Links ]

WEYMES E. 2004. A challenge to traditional management theory. Foresight: The journal of future studies, strategic thinking and policy. Vol.6, issue 6. Available on-line from: http://www.emerald.com (accessed 20 July 2007). [ Links ]

WISSE J. 2002. The Reformation. Timeline of art history. Available from: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/refo/hd_refo.htm (Accessed 7 April 2008). [ Links ]

WREND.A. 2005. The History of Management Thought. Wiley: Hoboken. [ Links ]