Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.5 n.1 Meyerton 2008

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Proposing and evaluating a model for ethical recruitment and selection

HE Brand

Department of Human Resources Management, University of Pretoria

ABSTRACT

Effective recruitment and selection are strategically important to any organisation. Recruiting and selecting the wrong candidates can have extensive negative cost implications, while effective processes in this regard can contribute to a decrease in staff turnover and an increase in productivity.

After the passing of the new Labour Relations Act of 1995, all employers had to revisit these processes in order to also evaluate its measure of fairness and justness, focusing also on the ethical nature and value thereof. This study aims at the proposal and evaluation of a model that incorporates ethics in the recruitment and selection process. Qualitative and quantitative research methodology were utilized within a model-building research framework.

Key phrases: Recruitment, selection, business ethics, human resource management ethics, model building methodology

INTRODUCTION

It is commonly accepted that sound ethics management is an essential part of modern day business. Unethical behaviour can have devastating consequences for an organization, while sound ethical behaviour can give an organisation a competitive edge. An acknowledgement of the importance of business ethics is more than a mere commitment to be ethical, but requires the establishment of a corporate ethical capacity in a concerted and structured way. Thus it is vital that managers should be competent in managing the ethical dimensions of their business.

Since it is unlikely that a constellation of rule governing the practice of human values, such as can be found in the domains of, for example accounting and science, will ever be invented, value-driven governance in sync with the management of ethics, offers a crucial starting point for transforming the ethical orientation of organisations while enhancing financial performance (Bartlett & Preston 2000). In order to produce sustained ethical behaviour, an ethical way of thinking (ethical organisational culture) and doing (ethical behaviour) needs to be cultivated. Management needs to set specific ethics objectives for their organisation, design and implement a strategy to achieve these objectives, institutionalize ethics and monitor and report on the ethical performance of organisation members (Seidenberg 1998).

According to Kreitner and Kinicki (1992), as well as Joyner and Payne (2002), ethics in general involves the study of moral issues and choices. Business ethics concerns the study of conflict between economics and values, between competition, commerce and capitalism, and between morality, integrity and responsibility (Virovere et al 2002; Hatcher 2002). Business ethics is therefore the examination of values and the way values are carried out in work-related systems. Morris, Schindehutte, Walton and Allen (2002) define ethics as dealing with the distinction between right and wrong, and it is concerned with the nature and grounds of morality.

When looking at ethics in the domain of human resource management, ethics is a prerequisite for the reputation and sustained financial performance of a company and should be a foundation element in human resource management strategy (Petrick & Manning 1990). According to Feldman (2002), a people managing philosophy based on a reconstituted psychological contract would consist of five facets, which must mutually support one another. These facets are:

• The ethical facet (how should people be treated)

• The process facet (how should people be related)

• The structural facet (how should the relationship with people be formalized)

• The content facet (how should people be viewed)

• The outcome facet (how should people benefit from the relationship)

Human resource management should also adopt ethical and socially responsible models, processes and codes. Stead, Worrell and Snead (1990) suggest that there are certain ethical-driven actions which can be taken whilst executing a human resource management strategy. These actions are:

• Behave ethically yourself

• HR managers are potent role models - their behaviour send clear signals about the importance of ethical conduct

• Screen potential employees through a proper (fair & just) recruitment and selection process

• Check references, credentials and other information of applicants

• Develop a meaningful code of ethics, which is distributed to every employee, is firmly supported by top management, refer to specific practices and ethical dilemmas, and is evenly enforced with rewards for compliance and clear penalties for non-compliance.

• Provide ethics training. Employees should be trained to identify and deal with ethical issues.

• Reinforce ethical behaviour via policies and procedures, various communication channels and illustrated leadership.

• Create positions, units and structural mechanisms to deal with ethics. Some companies even have ethics managers/directors at corporate level, as well as ethics hotlines.

The need for a uniform code of ethics in South Africa arose after the professionalization of human resource management. Most professions have their own ethical codes. According to Van der Westhuizen (1998), a comparison of the guidelines in the ethical codes of The Psychological Association of South Africa, the Health Professions Council of South Africa, the Labour Relations Act, Basic Conditions of Employment Act, Employment Equity Act and the Skills Development Act, brought forward some issues of importance to consider with regards to recruitment and selection ethics in human resource management. The human resource management practitioner has the duty to ensure that ethics take priority in these processes. These issues are:

• Companies should adopt the realistic recruitment approach by presenting candidates with relevant and undistorted information about the job and the company/organisation. Greenhaus (2000) also refers to this issue and mentioned that this could assist in reducing the voluntary turnover in the company, as most applicants have unrealistic job expectations before joining the company and then suffer from reality shock soon after starting employment. It would be much easier to settle into a position if all relevant information about the position, positive and negative, was presented during the selection interview.

• Interviews are subjective and prone to human error and bias. It is therefore important that more structured interviews are used to ensure less prejudice and/or discrimination against any applicant.

• The administration involved in the receiving and processing of applications could also be not as efficient as expected. In general, due to workload, most organisations do not notify applicants that their curriculum vitaes and other documentation have been received, with an explanation on how long the process of selection thereafter will take. Many unsuccessful applicants never receive a letter of regret and have to phone, for example, the company's human resource management department to enquire about their application.

• Confidentiality is not always adhered to as expected and requested by applicants. Many current employers of applicants are phoned to attain information, even in cases where applicants requested that this should not be done.

• With internal appointments many managers already know who they want to appoint and merely go through the entire recruitment and selection process, only to cover themselves from issues such as possible disputes from unsuccessful applicants (for example disputes serving at the CCMA).

• Clever tactics of management concerning the management of affirmative action could also be seen as unethical. Managers often appointed members from the designated groups, only to set them up for failure in their jobs. No support, training and managed responsibility were provided to these employees, resulting in poor performance, which in turn serves as a confirmation to managers that affirmative action appointments cannot succeed (Chapter 3 of The Employment Equity Act 55 of 1998 provides clear guidelines on affirmative action management).

According to Schumann (2001), it is unethical for a manager to refuse to hire a well-qualified applicant because of prejudice concerning some characteristics of the applicant which are irrelevant to the job (for example the applicant's race).

There is a growing recognition that good ethics management can have a positive economic impact on the performance of organisations, and studies support the premise that ethics, values, integrity and responsibility are acquired in business (Van der Westhuizen 1998). According to Joyner and Payne (2002), there is a general realization that business must participate in society in an ethically symbiotic way. A fundamental truth is that business cannot exist without society and society cannot prosper without business.

Effectively managing ethics requires that the human resource management professional/practitioner engages in a concentrated effort to help establish ethical behaviour in the company. This effort involves, inter alia, espousing ethics, behaving ethically (role model), developing screening mechanisms for potential employees, providing training on ethics, supporting organisations on creating ethics units, measuring ethics and reporting on it (ethics audit), as well as rewarding ethical behaviour (Van der Westhuizen 1998). Paramount to the before mentioned is ethical leadership. The management of ethical behaviour must also be done via a holistic and systemic strategic approach and it is also of extreme importance that all stakeholders realize the importance of the issues at hand (Roberts 2005). It is not merely a fashion trend, but ultimately about long-term corporate survival and in the macro environment about the long-term harmonious existence of all people (Roberts 2005).

An ethical organisation is one that has a strong ethical value orientation, truly live out these values and practices them when engaging with all its internal and external stakeholders (Searle 2003). Seidenberg (1998:11), the CEO and chairman of Bell Atlantic, emphasizes this notion as follows:

"Organisations can no longer rely on traditional modus operandi ....new behaviours grounded in business ethics are urgently required to ensure continued stakeholder trust".

An ethical value orientation is therefore strongly linked to the practice of good corporate governance that aims at satisfying the needs of all stakeholders. As such, an ethical organisation will voluntarily comply with the requirements of good corporate governance and participate in related activities and forums unconditionally. It stands to reason that any organisation that has a reputation for good corporate governance and ethics will be able to attract investors for whom such governance is of major importance, to attract ethically discerning customers and be a preferred employer for people who perceive themselves as having the capacity to thrive in an environment that fosters ethical behaviour (Van der Westhuizen 1998).

An overt, structured attempt at continuously managing corporate ethics is also made in ethical organisations. This is brought about by managing ethics strategies and systems using a corporate ethics function (Wood 1998). This function, which would typically be co-ordinated by an ethics manager or officer, ensures that the organisation has a strong code of ethics that is understood and applied by all employees. The corporate ethics function, in conjunction with all management cadres, is also responsible for creating and maintaining an ethical organisational culture. Evidence of the existence of such a culture includes high levels of trust, the presence of spontaneous "moral talk", the continuous consideration of ethical implications of decisions at all levels, the presence of several ethical role models in key positions and ethical human resource management practices (Wood 1998).

Organisations in an advanced stage of ethical development implement their ethics strategies successfully and achieve their ethics goals. Ethical organisations not only survive formal ethics audits conducted by independent auditors, but also excel when they subject themselves to this type of scrutiny (Herriot 1989). Reporting on ethics and disclosure to stakeholders is then done with confidence. Any negative feedback received is viewed as constructive criticism and acted on immediately (Edenborough 2005).

Against the discussed background, the purpose of this study was to propose and evaluate a recruitment and selection model that incorporates ethics in the recruitment and selection process in the organisation.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Research method

Qualitative and quantitative research methodology are used in this study with the aim of proposing and testing a model that incorporates ethics in the recruitment and selection process. An extensive literature study was done to determine the steps in these processes, as well as the possible ethical implications related to these steps.

The literature analysis process can be divided into three phases. During phase one a theoretical overview on the concepts of recruitment and selection was obtained. During phase two the guidelines for ethical recruitment and selection were identified. During the third phase an integrated management approach or model was postulated, based on the information and guidelines from the previous phases.

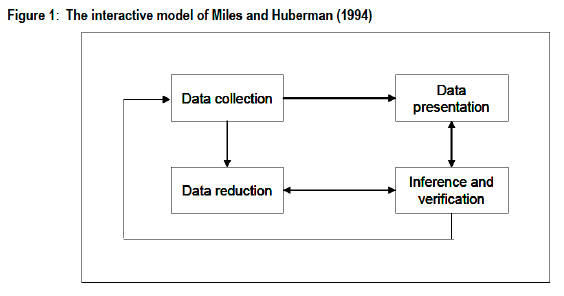

The qualitative research methodology used in the literature analysis is based on the interactive model of Miles and Huberman (1994). This model and its steps is depicted in Figure 1:

The steps of the model can briefly be described as follows (Miles & Huberman 1994):

Data collection

The relevant data collected appears in word format, rather than numbers. The data was collected from studying and analyzing literature in the form of books, articles and legislation.

Data reduction

This relates to acquiring, simplifying and processing the raw data collected. The data is sorted, processed and organized in such a manner that it facilitates the process of final inference (Petersen 1998). The collected data was reduced according to the main themes of recruitment, selection, orientation and ethics.

Data analysis

Concept analysis and reconstruction techniques were used. It consists of analyzing theory and identifying basic elements relevant to the development of an integrated ethical approach in the recruitment and selection process.

Data presentation

This involves an organized way of information collection, which facilitates the process of making inferences. In order to make meaningful inferences, the information is presented in table and figure format.

Inference and verification

This consists of the scientific evaluation of the integrated approach of ethics in the recruitment and selection process, according to specific criteria. The appropriateness and usefulness of such an approach can therefore be determined. A panel of experts (selected according to certain quality criteria) was used to determine the validity of the approach.

Developing an integrated model

Definition of a model

According to Dye (1995), a model is developed from theoretical relationships between different elements of a certain subject being researched. A model thus is a simplification of relevant objects, situations and behavioural patterns. The purpose of a model postulated is to understand a problem or subject matter better, as well as the possible effect of different behaviours. However, according to Vennix (1996), the role of a model is not to supply pre-determined, formulated decisions of possible solutions in certain situations. A model provides guidelines from which decisions can be taken, but these decisions cannot be based only on the content or nature of the model. An integrated ethics model for recruitment and selection should provide a simple description of a complex process, and should provide clear and objective guidelines to ensure that ethics can be practiced during these human resource provision processes.

The composition of a model

Vennix (1996) explains that a clear purpose and problem should exist before a model can be developed. By analyzing the purpose and problem intensively, choices can be made regarding the inclusion or exclusion of certain elements in the model. Dye (1995:40) identifies certain criteria for the successful development of a model. These criteria are:

• A model should be explicit, so that it can be easily understood, evaluated and compared to other models.

• It should be congruent with reality and have empirical references.

• It should lead to the observation, measurement and verification of theory and research.

• It should be logically composed and have face validity to ensure that it can be used as a method of communication.

Steps in the development of a model

The steps proposed by Vennix (1996) were followed in this research. These are:

Problem identification and purpose of the model:

A clear purpose of the study/research is necessary in order to focus it and to eventually make a decision regarding the elements to be included in the model. The purpose of the model is to understand the problem better, as well as the potential consequences of possible actions.

Model formulation and determination of parameters:

The relationships of elements in the model are firstly determined and parameters are then established.

Analysis of model behaviour testing and sensitivity analysis:

One of the most important steps in developing a model is the testing thereof. The primary purpose of this is to understand the model behaviour and to obtain more insight into the system that is studied by means of sensitivity analysis.

Model evaluation - determining model validity:

Model validity can be determined in different ways. In this study a qualitative evaluation approach was used to determine the validity of the model. Vennix (1996) concluded in this regard that:

• Absolute models do not exist (it is always a simplification and representative of a system)

• A model's validity can only be judged in the light of its purpose

• A clear distinction has to be made between a model's validity and use. A valid model is not necessarily useful. The more complex a model becomes, the less value it can have in terms of its usefulness.

• The specific validity of a model can never be fully determined and therefore the validity is equal to the level of trust in the people who developed it, as well as the client trust in the model. Forrester and Senge (in Vennix 1996) state that trust is the main criterium, as the absolute correctness of the model cannot be proven.

Content validity of the model:

Lawsche's technique for the determination of content validity was used in this study (Lawsche 1975). With this technique content validity can be quantified to be generally acceptable. Briefly, this technique includes the following:

A panel of experts in a specific field is requested to judge certain aspects of the proposed model. This content evaluation panel receives a number of questions or items from the proposed model and have to evaluate these items in terms of the validity thereof in the model. The different valuations from the panel are then consolidated and the specific value of the judging is determined. Two important assumptions are made, namely that any item evaluated as important or very applicable has some content validity, and that the more panel members (50 percent and above) see an item as important or very applicable, the higher the content validity of that item.

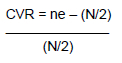

The following formula according to Lawsche (1975) is used for determining the content validity ratio (CVR) of items:

Ne indicates the number of people on the panel that selected an item as important or very applicable, and N indicates the total number of panel members.

If a larger number of panel members selected an item as important or very important, the CVR will be negative. Where half the panel members selected an item as important/very applicable and the rest are of the opposite opinion, the CVR will be zero. Where all members selected an item as important, the CVR will be 1.00, but adjusted to 0.99 to simplify manipulation. Where the number of panel members who chose items as being important or very applicable is more than half the panel but not all, the CVR will be between zero and 0.99.

To determine the content validity of the model, it is necessary to do the following:

1 ascertain the determinants which have meaningful CVR values

2 calculate the average content validity index for the whole approach

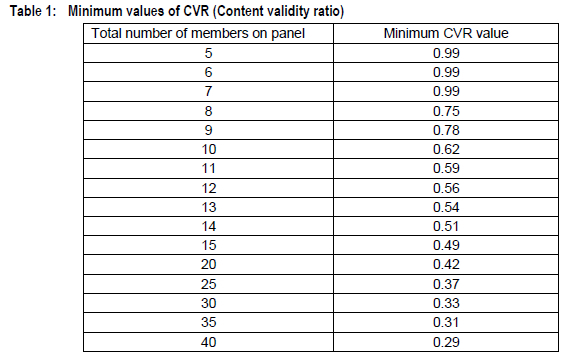

A minimum CVR value of .42 is required. This requirement is determined by the number of experts on the evaluation panel. Only the items adhering to this requirement will be included in the final model. After determining these items, the average content validity index for the rest of the items is calculated. Table 1 depicts the minimum values of CVR (Lawshe 1975).

RESULTS OF THE STUDY

The panel of experts evaluating the model items

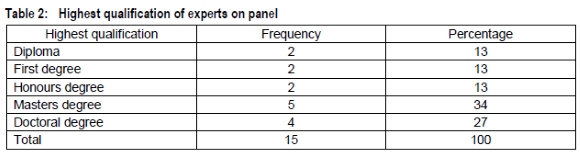

The members selected for the evaluation panel have extensive experience in the field of human resource management, obtained through learning (qualifications), work experience in the various fields of human resource management and exposure on different levels of management in their respective work environments. These identified individuals were approached and their consent obtained to act as evaluators on the panel of experts for the purpose of this study.

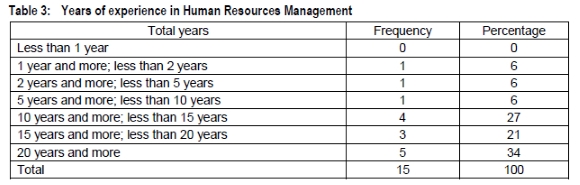

Their biographical information in terms of qualifications and years of experience in the field of human resource management is provided in tables 2 and 3.

Table 2 indicates that the panel members have qualifications ranging from a first degree to a doctorate degree in the fields of human resource management/ Industrial and Organizational Psychology. The majority possess a masters or doctoral degree.

Table 3 indicates that the panel members possess a wide range of experience in the fields of human resource management/Industrial and Organisational Psychology. The majority of the members have experience of 10 and more years.

Model evaluation and content validity determination

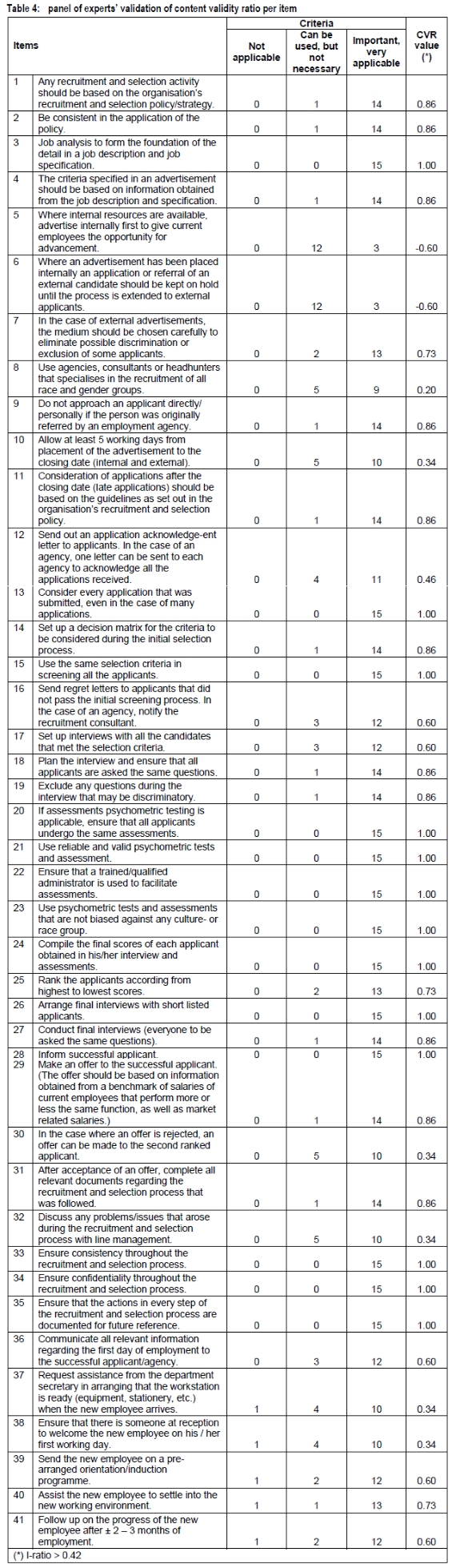

The panel members each received an item list consisting of proposed or possible items to be included in a model that incorporates ethics in the recruitment and selection process, and were asked to evaluate each item according to the criteria of: not applicable, can be used but not necessary and important/very applicable. The item lists were e-mailed to the members, including information detailing the purpose of the study as well as the necessary instructions for completing the evaluation. All the members completed the item list and 15 evaluated lists were received back either by email or fax.

Lawshe's formula (Lawshe 1975) was used to calculate the content validity ratio of each item.

Table 4 depicts the content validity ratio of each item, as well as the responses of each panel member on these items.

Therefore these items are not included in the proposed model that includes ethics in the recruitment and selection process. Panel members were also asked to comment on or make suggestions regarding the changing of items or adding of items to the existing list. No such feedback was received, leaving the assumption that the panel of experts was satisfied that all the applicable and necessary information was included in the item list.

The integrated model

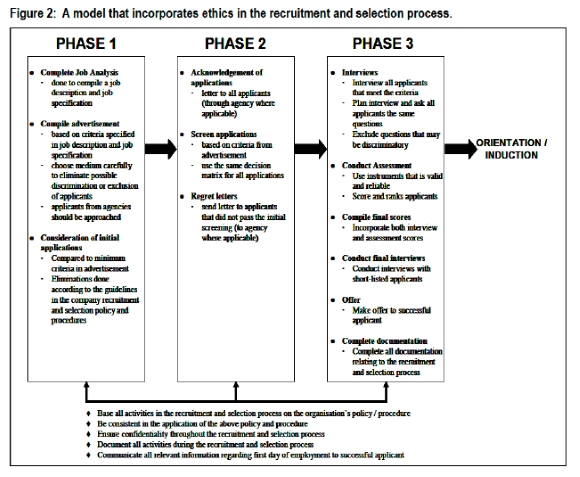

Based on the content validity ratio values obtained, the model that incorporates ethics in the selection and recruitment process was determined.

Figure 2 depicts this model.

The items contained in the various phases of the model are not explained again, as they have been described in the model framework.

Items 1 to 11 from the item list were incorporated in phase 1 of the model, and comprises of the activities of completion of a job analysis, compiling the advertisement and consideration of initial applications.

Items 12 to 16 from the item list were incorporated in phase 2 of the model. This phase comprises of the activities of acknowledgement of applications, screening of applications and regret letters.

Items 17 to 38 from the item list were incorporated in phase 3 of the model, and comprises of the activities of arranging and conducting interviews, conducting assessments, compiling final scores, offers made (to successful applicants) and completing of documents.

CONCLUSION

The final model that includes ethics in the recruitment and selection process is the product of a thorough process of information gathering, planning and evaluation. This model can be utilized by organisations and can be further evaluated, developed and adapted according to their own realities and needs in terms of ethical recruitment and selection.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BARTLETT A. & PRESTON D. 2000. Can ethical behaviour really exist in business? Journal of Business Ethics, 23(2):199-209. [ Links ]

DYE T.R. 1995. Understanding public policy. 8th Edition. Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. [ Links ]

EDENBOROUGH R. 2005. Assessment methods in recruitment, selection and performance: a manager's guide to psychometric testing, interviews and assessment centres. Sterling: London. [ Links ]

FELDMAN D.C. 2002 The multiple socialization of organization members. Academy of Management Review, 6(2). [ Links ]

GREENHAUS J.H. 2000. Career Management. Harcourt College Publishers: Orlando, USA. [ Links ]

HATCHER T. 2002. Ethics and HRD: a new approach to leading responsible organizations. Perseus: Cambridge. [ Links ]

HERRIOT P. 1989. Assessment and selection in organizations: methods and practice for recruitment and appraisal. Wiley: New York. [ Links ]

JOINER B.E. & PAYNE D. 2002. Evolution and implementation: a study of values, business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 41(4):297-311. [ Links ]

KREITNER R. & KINICKI A. 1992. Organisational Behaviour. Irwin: Boston. [ Links ]

LAWSHE C.H. 1975. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology, 28:563-575. [ Links ]

MILES M.B. & HUBERMAN A.M. 1994. Qualitative data analysis : an expanded sourcebook. 2nd Edition. Sage Publications: USA. [ Links ]

MORRIS M.H., SCHINDEHUTTE M., WALTON J. & ALLEN J. 2002. The ethical context of entrepreneurship : proposing and testing a developmental framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 40(4):331-361. [ Links ]

PETERSEN R.J. 1998. Die beste van 'n diverse werksmag in die Israeliese besigheidsomgewing en die moontlikheid van paralelle toepassing in Suid-Afrika. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Pretoria. Pretoria. [ Links ]

PETRICK J.A. & MANNING G.E. 1990. Developing an ethical climate for excellence. The Journal for Quality and Participation, 84-90, March. [ Links ]

ROBERTS G. 2005. Recruitment and selection, Institute of Personnel and Development. London. [ Links ]

SCHUMANN P.L. 2001. A moral principles framework for human resource management ethics. Human Resource Management Review, 93-111, November. [ Links ]

SEARLE R. 2003. Selection and recruitment: a critical text. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke. [ Links ]

SEIDENBERG I. 1998. Ethics as a competitive edge. The Sears Lectureship in Business Ethics. Bentley College: Waltham, MA. [ Links ]

STEAD W.E., WORREL D.L. & SNEAD J.G. 1990. An integrative model for understanding and managing ethical behaviour in business organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 233-242, March. [ Links ]

VAN DER WESTHUIZEN E. 1998. Die ontwikkeling van 'n billike en regverdige werwing - en keuringsproses, Unpublished masters dissertation, University of Pretoria Pretoria. [ Links ]

VENNIX J.A.M. 1996. Group model building. England: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

VIROVERE A., KOOSKARE M. & VALLER M. 2002. Conflict as a tool for measuring ethics at the workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 39 (1/2):75-81. [ Links ]

WOOD R. 1998. Competency-based recruitment and selection. John Wiley: Chichester. [ Links ]