Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.5 no.1 Meyerton 2008

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Stakeholders' perceptions of city improvement districts: the case of Rondebosch / Rosebank

K Cattell; P Bowen; K Michell

Department of Construction Economics and Management, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

The study reported here was undertaken to gauge stakeholders' perceptions in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area of Cape Town with the aim of using these views to guide the design of a possible City Improvement District (CID) for the area. Several surveys and some follow-up structured interviews were conducted. The surveys involved commercial property owners (21), commercial tenants (50), residents (102), shoppers (101) and students (1371). The questionnaires covered the areas of safety and security, litter/grime and cleaning, parking, informal trading, public transport, the public environment, and social issues.

The main finding in respect of safety and security was that it was ranked by all respondent types as the most serious problem in the area. A common complaint is the apparent lack of visible policing. Whilst the cleanliness of the Rondebosch / Rosebank area appears to be 'acceptable', graffiti is perceived as a nuisance. The availability of on-street parking is considered inadequate and vehicles parked on the street are not considered secure. Car guards are seen as annoying or threatening by many. Whilst the concept of informal trading enjoys wide support in principle, the majority of stakeholders want it to be managed by the local authority in specific ways. Mini-bus taxis are not viewed positively and the majority of respondents consider taxis to have a negative impact on the image of the area. The quality of the public environment is well regarded, although the maintenance of pavements and street lighting is seen by some as a problem. Whilst there is considerable tolerance of street children, vagrants and homeless people are perceived to detract from the image of the area, display threatening behaviour, and harass people for food and/or money.

A clear majority of participants would support the introduction of a Rondebosch / Rosebank CID.

Key phrases: City Improvement District, CID, Rondebosch / Rosebank, Cape Town, South Africa

1 INTRODUCTION

City Improvement Districts (CIDs) are non-profit companies representing property owners (ratepayers) in a geographical area within a municipality. A CID makes an agreement with the municipality so that more money (a CID levy) can be collected from ratepayers in the area over and above the normal rates charges. This extra money is used to give 'top up' services in the area covered by the CID. The extra services usually include extra security and cleansing. CIDs have also been called Commercial Improvement Districts (CIDs) or Residential Improvement Districts (RIDs) (City of Cape Town 2006). CID's are known as Business Improvement Districts (BID) in North America and Europe (PUR 2000a, 2000b).

The CID levy is a dedicated levy: the money raised from the levy must go to the CID. This means that the levy must be used for services in terms of the business plan agreed to by property owners in the CID and cannot be redistributed for use outside the CID. Levies charged to property owners are sometimes paid by property owners, or sometimes passed on to tenants, in the same way that rates are.

Benefits flowing from the establishment of a CID are claimed to include: the defined area gets enhanced, which results in a strengthening of investors' confidence; a positive identity for the area is created; 'crime and grime' are reduced; the success of the CID is measurable; new developments and/or interventions in the area are planned and monitored; and the CID is able to discuss with the council ideas for changes in the area (see Central Johannesburg Partnership 2007). Hoyt (2005), in an examination of the effect of BIDs on crime in and around Philadelphia's commercial areas, concludes that BIDs are successful in reducing crime without a spillover effect into neighbouring areas.

Hoyt and Gopal-Agge (2007) present a useful overview of the literature on business improvement districts (BIDs) by highlighting its historical underpinnings, identifying the economic and political factors that explain its transnational proliferation, and demonstrating how the model varies within and across nations. Their paper also provides a balanced review of the key debates associated with this relatively new urban revitalization strategy by asking the following questions: Are BIDs democratic? Are BIDs accountable? Do BIDs create wealth-based inequalities in the delivery of public services? Do BIDs create spillover effects? Do BIDs over-regulate public space? They conclude that the BID model represents a success story because it generally functions to harness private sector creativity, solving complex municipal problems efficiently and effectively. However, they point out that BIDs have blurred the line between the traditional notions of 'public' and 'private'. Interested readers are also referred to Blackwell (2005) and Ratcliffe and Flanagan (2004).

This paper documents the findings emanating from an empirical study of the perceptions of a number of stakeholder groups (students; residents; commercial property owners; commercial tenants; and shoppers) in the Rosebank / Rondebosch area regarding 'crime and grime'. The purpose of the study was to provide a contextual background to establishing the extent to which the introduction of the CID (Community Improvement District) in the area would be supported by the stakeholders.

2 CITY IMPROVEMENT DISTRICTS IN CAPE TOWN

The process for the establishment of a CID in the City of Cape Town is strictly regulated (see City of Cape Town 2000). Any rate-paying owner of property can apply to the Cape Town Council for a CID to be approved. The applicant must pay all costs involved in the application process. The management body of the CID eventually created can reimburse some of these costs to the applicant if the application is successful. The process involves advertising for a public meeting to be held, the holding of a public meeting to discuss the CID, submitting a written application which must include an improvement plan, payment of a fee to the Council, advertising the application and considering objections to the application, obtaining a Council decision, and gaining majority support from ratepayers in the designated area. The initial application must have the written support of at least 25% in number of the owners of ratable properties in the area, and such owners must represent 25% of the rates-based value of the properties in the area. If the Council approves the application, the CID must, within six months of approval, obtain the written agreement of property owners in the area that together own at least 50% of all properties in number and at least 50% of the rates base. Only once this majority agreement has been obtained can the management body implement the City Improvement District Plan (City of Cape Town 2006).

An example of an established City Improvement District is the Cape Town Central City Improvement District (Cape Town Partnership 2007) This CID covers the areas bordered by these roads in central Cape Town: Buitengracht, Buitensingel, Orange, Grey's Pass, Queen Victoria, Wale, Spin, Plein, Roeland, Canterbury, Darling, Castle, Strand, Adderley, Heerengracht, Old Marine, Civic, Hertzog Boulevard, Oswald Pirow and Table Bay Boulevard. The Cape Town Partnership (2007) manages the Cape Town Central CID (City of Cape Town 2006). Other operational CIDs in Cape Town include the Claremont CID (CIDC 2007) and the Wynberg CID. Cape Town CIDs in various stages of development include: the Green Point CID, the Oranjekloof CID, the Higgovale CID, the Sea Point CID, and the Camps Bay CID. The City of Cape Town has drafted municipal legislation for the regulation of CIDs (City of Cape Town 2000).

The Rondebosch / Rosebank area of Cape Town, located approximately 5km from the city centre, is home to the University of Cape Town (UCT). UCT, as the single, largest property owner in Rondebosch / Rosebank, has a vested interest in ensuring a safe, secure, and clean environment for its approximately 24 000 students and staff. Rondebosch, in common with most city suburbs in South Africa, suffers from unacceptably high levels of crime. The magnitude of the problem in Rondebosch and environs can be gleaned from extracts from crime statistics supplied by the SAPS (2007) for the period April 2006 to March 2007: 2 murders, 3 attempted murders, 7 rapes, 3 indecent assaults, 67 common assaults, 424 robberies with aggravating circumstances, 26 car-jackings, 13 robberies at residential premises, 304 thefts of cars or motor cycles, 533 thefts from or out of cars or motor cycles, and 1 abduction. Clearly the situation is far from ideal and positive interventions are required. Arguably, one vehicle for the urban regeneration of the area would be creation of a CID. This study gauges the extent to which such an initiative would be supported by stakeholders.

3 METHODOLOGY AND QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN

A qualitative methodology, employing questionnaires and interviews, was adopted for the study. Structured interview questionnaires were applied to the business owner, commercial tenants, and shopper groups of stakeholders. The opinions of UCT students were canvassed using a web-based, online questionnaire survey. The perceptions of residents were gleaned by use of structured questionnaire surveys applied by means of a mail slot. More detailed, follow-up interviews were undertaken (on a limited basis) on residents and students who agreed to provide further information.

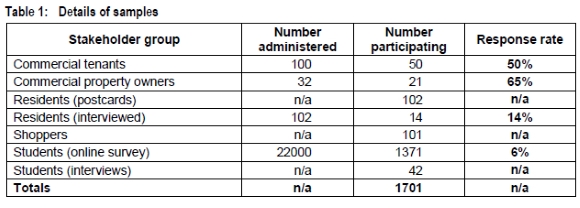

The design of the questionnaires was based upon questionnaires used for a similar study undertaken in the Claremont area of Cape Town. Changes were, however, made for reasons of location and stakeholder characteristics. Moreover, questions for the follow-up interviews of students and residents were designed specifically for that purpose. Copies of the questionnaire may be obtained from the authors, but the report is structured around the questions, so they will be self-evident. Details of the sample sizes of the participating stakeholder groups are as follows:

A total of 1701 people actively participated in the survey, which took place in May and June 2007. Given the nature of the source populations it is not possible to provide an overall response rate, suffice it to say that the number of participants is considered adequate in providing an indication of perceptions of stakeholder groups.

The data were captured on spreadsheets (manually, or automatically in the case of the online survey) and analysed using SPSS for Windows. The statistical analysis is limited to percentages and is indicative of trends. Cross tabulation analyses and tests for statistical significance were not undertaken for the purposes of this paper.

The following sections deal specifically with the main findings relating to the foci of this empirical study, namely: safety and security; litter, grime and cleaning; parking; informal trading; public transport; public environment; and social issues. Respondents were also required to rank the above factors in importance to them. Finally, they were asked whether they felt that a CID was warranted and, if so, would they support it. Thereafter, conclusions are provided.

4 DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

Whilst the questionnaires to each participating group were similar in nature, certain differences were necessary to capture the particular flavour of each group. Notwithstanding the attempt at group-specific questions, certain questions were common to all stakeholder groups. The analysis presented in this section relates only to questions posed to all groups.

It needs to be noted that the opinions of residents secured via the postcard survey are completely excluded from the analysis presented in this paper as the questions posed to that group were largely unique. However, the analysis given below includes the data captured via the follow-up telephonic interview survey to those residents who (on the returned postcards) had provided their contact details and had expressed a willingness to be interviewed in more depth. Those particular residents were then subjected to a more detailed survey (termed 'residents long') that corresponded to a large degree to those surveys applied to the other groups.

4.1 Safety and security

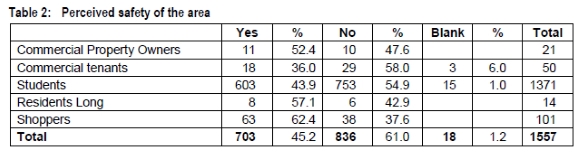

Q1. Do you feel safe in and around the public environment in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area?

The shoppers group appears to feel the safest of all participating groups, with 62% claiming to feel safe in the area. Conversely, 38% do not. All other groups display perceptions of feeling less safe in the area, with the majority of both the commercial tenants (58%) and students (55%), respectively, feeling 'unsafe'. The above figures relate to sample size. Interestingly, 61% of responses reported in the table below are from those who perceive the area to be unsafe.

4.2 Litter, grime and cleaning

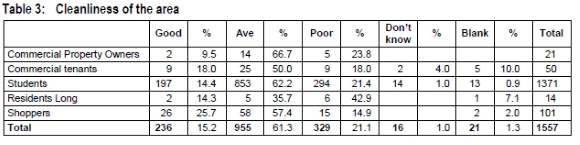

Q2. How do you rate the overall cleanliness of the area?

Most (61%) respondents describe the cleanliness of the area as 'average' and a further 15% describe it as 'good'. Thus, overall there does not appear to be a problem. However, 21% describe it as poor - this largely reflects the views of residents. Except for the shoppers group (26%), no more than 18% of any of the other participating groups describe the overall cleanliness of the area as 'good'. Whilst a majority of each group (in terms of sample), with the exception of the residents (36%), claim that the cleanliness of the area is 'average', significant proportions of all groups but one state that it is 'poor' - commercial property owners (24%); commercial tenants (18%); students (21%); and residents (43%). The shoppers are the dissenting group with only 15% claiming it is 'poor'.

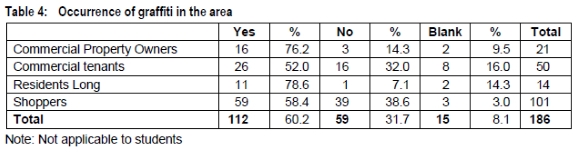

This question was not posed to the students via the on-line survey. A clear majority of all other types of stakeholders combined indicate that graffiti does occur in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area. As would be expected, such graffiti appears to be most noticeable to the commercial property owners and the residents, with 76% and 79% of these two groups, respectively, stating that graffiti is present.

4.3 Parking

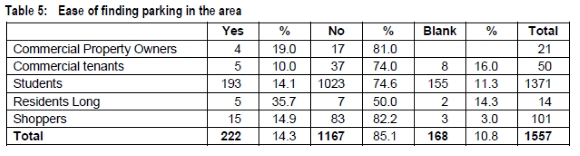

Q4. Do you find it easy to find a parking space?

A majority of all groups responding to this question report that parking is not easy to find in the area. Most vociferous of these are the commercial property owners (81%), commercial tenants (74%), students (75%), and shoppers (82%). These quoted figures relate to respondents to this particular question. The statistics are not too dissimilar when considered in terms of sample size. A majority of residents state that parking is a problem. It is also likely that student responses reflect their own reality -i.e. that parking on campus (as opposed to Rondebosch / Rosebank in general) is a problem.

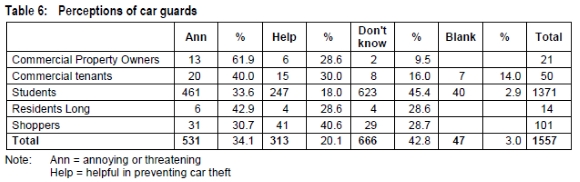

Q5. What is your perception of the car guards currently working in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area?

Opinion regarding the issue of car guards in the area appears somewhat diverse. In terms of overall group sample sizes, none of the groups hold a majority view that the guards are helpful. The majority of commercial property owners see car guards as being annoying. Overall, 34% of the total sample sees the car guards as annoying.

4.4 Informal trading

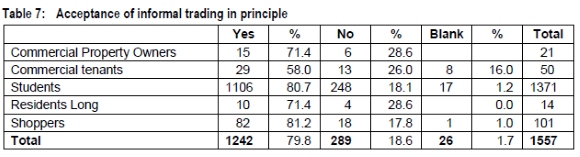

Q6. Do you support the concept of informal trading in principle?

Interestingly, all groups appear to support in principle the concept of informal trading in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area. This is perhaps somewhat surprising with regard to commercial property owners (71%) and commercial tenants (58%), given that informal traders are arguably in competition with them for the passing trade. The local residents are also supportive (71%), as are the students (81%).

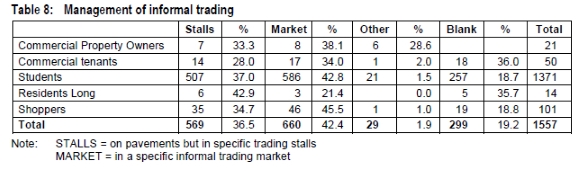

Q7. If your answer to Q6 was "yes", which of the following managed alternatives would you support?

Support seems fairly evenly distributed between the use of specific trading stalls and a specific informal trading market. Both forms of informal trading management appear to be supported in principle.

4.5 Public transport

Q8. What form of transport do you use to get to the Rondebosch / Rosebank area?

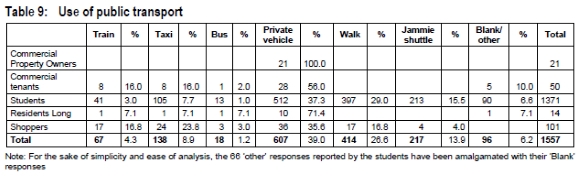

Reference to Table 9 indicates that all of the commercial property owner group use private vehicles to get to Rondebosch / Rosebank. A variety of transport means are used by the different groups to get to the Rondebosch / Rosebank area. The dominant means of transport of all groups appears to be that of the private vehicle; particularly the residents (71%) and the commercial tenants (56%). Walking is done predominantly by shoppers (17%) and students (29%), although not their primary means of getting to the area. The train service is utilized predominantly by commercial tenants (16%) and shoppers (17%), as are taxis (16% and 24%, respectively).

Q9. How do you perceive the mini-bus taxis in the area, in terms of obeying by-laws, their impact on the image of the area, etc. ?

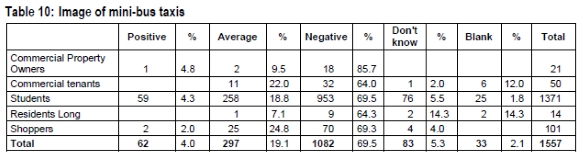

As depicted in Table 10, overall, most (70%) of the survey participants view mini-bus taxis as having a negative impact on the image of the area. Most emphatic of the various groups is the commercial property owner group (86%), students (70%) and shoppers (69%).

Q10. How well do you feel the mini bus taxis in the designated area are managed?

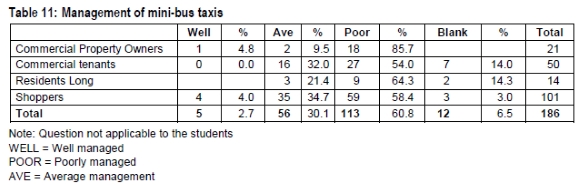

As would be expected from the responses presented above, the various respondent groups are overwhelmingly of the opinion that the mini-bus taxis are poorly managed (60% of total sample). Again, the commercial property owners appear to be most emphatic about this perception. Only 3% of the total sample feels that the taxis are well managed.

Q11. Are the train stations safe to use?

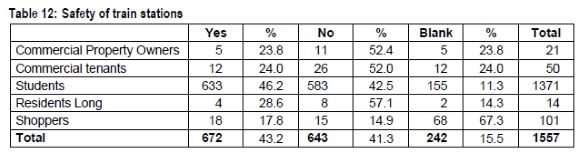

About 43% of all respondents feel that the train stations in Rondebosch / Rosebank are safe, while 41% consider them unsafe. When considered at a group level, in all participating groups, with the exception of the shoppers and students, the majority of the respondents (in terms of total sample and in terms of respondents to the question) feel that the stations are unsafe. Interestingly, the student group sees the stations in the most positive light. However, clearly, the stations are perceived as a crime spot.

4.6 Public environment

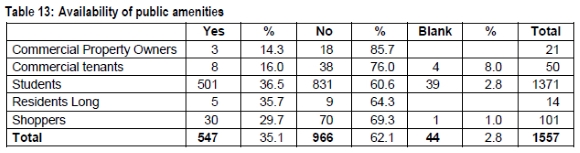

Q12. Do you feel that there are enough amenities in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area, such as information points, public toilets, parks, public seating etc?

The majority of all groups consider there to be insufficient public amenities in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area. This was more prevalent a view among commercial property owners and tenants, with a majority of 86% and 76%, respectively, reporting this.

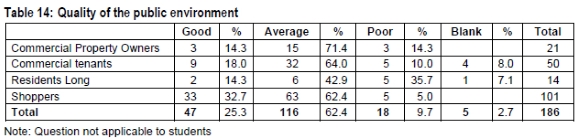

Q13. How would you describe the quality of the public environment, e.g. streets, pavements, building quality and maintenance etc.?

The majority of all participating groups consider the quality of the public environment in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area to be 'average' (65%) or 'good' (25%). Of these groups, the residents are the least enthusiastic with approximately 36% stating that the public environment is poor in quality.

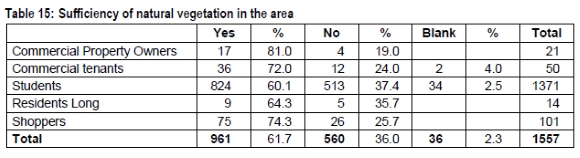

Q14. Are there enough natural elements in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area (e.g. trees, flowers, etc)?

A majority of 62% of all respondents are of the opinion that there is sufficient natural vegetation in the area. Commercial property owners, shoppers, and commercial tenants are the most enthusiastic about this (81%, 74%, and 72%, respectively). Students are the least supportive group (60%).

4.7 Social issues

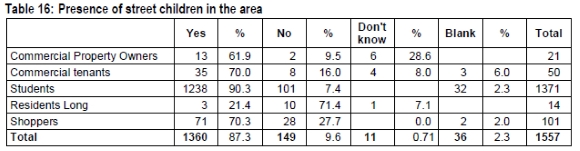

Q15. Are there street children in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area?

Whilst, in terms of the overall sample, 87% of the respondents indicate that street children are present in the area, opinion between groups is not unanimous about the issue. More specifically, the majority of the residents (71%) claim that street children are not in the area. This finding is surprising as one would expect that, of all the participating groups, the residents would be the most sensitive to the presence of street children. One possible explanation is that the street children are largely confined to the commercial areas; but one would still expect them to be detected by residents. Another explanation is that 14 responses from 1500 residents is too small a sample to permit any conclusion. Ninety percent (90%) of the student sample report the presence of street children - possibly biasing the analysis because of the large sample size. Except for the residents, a clear majority of all groups note the presence of street children.

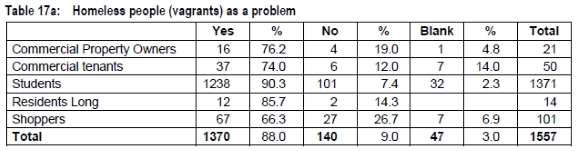

Q16. Do you see any of the following as being a problem in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area: vagrants; drug abuse /dealers; vendors and beggars?

Tables 17 a-c refer. Overall, 88% of the sample considers vagrants to be a problem. Whilst acknowledging them as a problem, the shoppers are slightly less unequivocal in this regard (66%) - perhaps because shoppers are temporary visitors to the area. Interestingly, the vast majority (90%) of students see the vagrants as a problem.

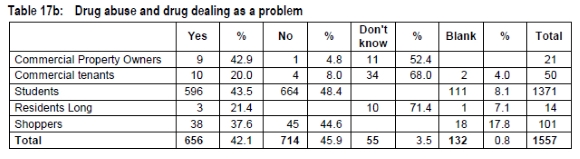

A majority of the sample of commercial property owners, commercial tenants and residents report not being in a position to tell ('don't know') if drug abuse and drug dealing is a problem in the area. This may be a function of the nature of their interaction within Rondebosch / Rosebank. Shoppers and students seem fairly evenly divided on the issue; with 40% of sample students and 38% of sample shoppers stating that there is a problem.

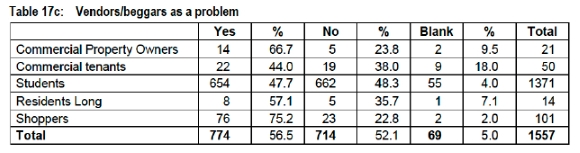

With regard to vendors and beggars being a problem, a sample majority of shoppers (75%), commercial property owners (67%), and residents (57%) see a problem. Sample minorities of both students and commercial tenants (although majorities in terms of respondents to the question) do not see a problem - with opinion within these two particular groups being fairly evenly split. Overall, 57% of the respondents see vendors and beggars as a problem.

4.8 Overall ranking of importance

Q17. Rank the listed factors in terms of importance

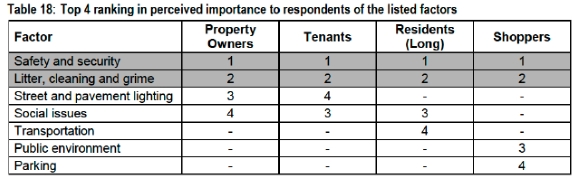

Commercial business owners, tenants, residents and shoppers were asked to rank, in order of importance to them concerning the Rondebosch / Rosebank area, the factors listed (1 = most important; 8 = least important). The results are summarised in Table 18. The ranking is determined by calculating the weighted average for each factor.

Clearly, all respondent groups see safety and security as the most important factor in relation to Rondebosch / Rosebank. Cleanliness (litter, etc.) follows close behind. The issues of the quality of the public environment, parking, lighting, social issues, and mini-bus taxis are all perceived as 'fairly similarly' important. Interestingly, the issue of street trading was perceived to be the least important - although such activities may adversely affect the quality of the public environment and generate litter and grime.

4.9 Support for a CID

Q18. Do you think a CID is warranted in the Rondebosch / Rosebank area and, if so, would you support it?

Finally, stakeholder groups were asked whether or not they felt a CID was warranted and, if so, would they support it. A clear majority responded positively to both questions.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has reported the findings of a study undertaken to gauge stakeholders' perceptions of the Rondebosch / Rosebank area with the aim of using these views to guide the design of a City Improvement District (CID) for the UCT-Rondebosch / Rosebank area. Several surveys and some follow-up structured interviews were conducted. The surveys involved commercial property owners, commercial tenants, residents, shoppers and students. The survey instrument in most cases was that used to inform the establishment of the adjacent Claremont CID, adapted as deemed necessary after the pilot studies for each stakeholder group had been conducted. The questionnaire covered the areas of safety and security, litter/grime and cleaning, parking, informal trading, public transport, the public environment and social issues.

The main finding in respect of safety and security was that it was ranked by all respondent types as the most serious problem in the area. The majority (61%) of those who were asked the question believe the area to be unsafe. Commercial property owners, tenants and residents were asked what they thought the main crimes are and 70% ventured opinions stating them to be (in order of frequency): muggings, shoplifting, theft from cars and armed robbery. Students and shoppers were asked if they had personally been victims of crime and 24% of them reported that they had experienced (in order of frequency) muggings, theft from cars and armed robbery. It follows that a common complaint is the apparent lack of visible policing in the area. The security in the area is not highly rated, and nor is the adequacy of the street or pavement lighting. Main Road, Rondebosch is generally considered to be a crime 'hotspot', but the train stations and the subways are also considered risky. Respondents want more visible policing, police patrols and security guards.

The findings regarding litter, grime and cleaning were that the cleanliness of the Rondebosch / Rosebank area appears to be acceptable (average or good) to the majority of those sampled. Only 20% rate it as 'poor'. However, graffiti is a nuisance, regarded so especially by commercial property owners, commercial tenants, and shoppers. Graffiti is not removed quickly. 'Litter, cleanliness and grime' is ranked (by commercial property owners, commercial tenants and residents) second only to crime as a problem in the area.

The availability of on-street parking is considered inadequate by 85% of the respondents and vehicles parked on the street are not considered secure. Car guards are seen as annoying or threatening by 34%. Only 20% of the respondents believe that car guards prevent the theft of cars.

The vast majority (80%) of all respondents support the concept of informal trading in principle. Although supportive of it, respondents want informal trading to be managed by the local authority in specific ways.

Public transport is underutlised and most respondents use private vehicles to get to and from the area. Walking is done predominantly by shoppers and students, although not their primary means of getting to the area. Lesser used modes of transport include the Jamie Shuttle, taxis and trains. Very few participants view minibus taxis positively and the majority of respondents consider taxis to have a negative impact on the image of the area. Taxi-related issues include poor management and informal/ad hoc formation of ranks.

The quality of the public environment is well regarded by most respondents. However, there are thought to be insufficient public amenities e.g. public toilets, information points, and public seating. It is also perceived by the majority that there are sufficient natural elements (flowers, trees, etc.) in the area, although a third of participants disagree with this assertion. The maintenance of pavements and street lighting is seen by some as a problem.

Social issues were ranked the third or fourth most serious problem, depending on type of respondent. The surveys confirmed that there are street children, vagrants, homeless people and beggars in the area. Although there is clearly considerable tolerance of street children, many residents see them as detracting from the image of the area, and report that they harass people for food and/or money. Respondents are less accommodating of vagrants and homeless people, who they believe detract from the image of the area, display threatening behaviour, and harass people for food and/or money. It is not entirely clear if there is a drug abuse or drug dealing problem in the area, but almost half of the respondents say that there is. Similarly, over half of the respondents consider beggars to be a problem

A clear majority of participants consider a CID to be warranted and would support its implementation.

Acknowledgements

This paper flows from a detailed study undertaken by the authors at the behest of the Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor at the University of Cape Town. The authors acknowledge, with thanks, the financial support of the University. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the University.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BLACKWELL M. 2005. A consideration of the UK government's proposals for business improvement districts in England: issues and uncertainties. Property Management, 23(3):194-203. [ Links ]

CAPE TOWN PARTNERSHIP. 2007. Cape Town Partnership. Available at www.capetownpartnership.co.za [Accessed on 4th December 2007]. [ Links ]

CENTRAL JOHANNESBURG PARTNERSHIP. 2007. Central Johannesburg Partnership. Available at www.cjp.co.za/initiator.php [Accessed on 4th December 2007]. [ Links ]

CITY OF CAPE TOWN. 2000.Bylaw for the Establishment of City Improvement Districts, PN 116/1999 Provincial Gazette 5337 dated 26 March 1999 amended PN 511/2000 29 September 2000. [ Links ]

CITY OF CAPE TOWN. 2006. Setting up a City Improvement District. Available at www.capegateway.gov.za/eng/directories/services/11459/9632 [Accessed 4 December 2007]. [ Links ]

CLAREMONT IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT COMPANY (CIDC). 2007. Claremont Central. Available at www.claremontcentral.co.za/cidc-about-us.html [Accessed 4 December 2007]. [ Links ]

HOYT L. 2005. Do Business Improvement Districts Make a Difference? Crime in and around Philadelphia's Commercial Areas. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 25(2):185-199. [ Links ]

HOYT L. & GOPAL-AGGE D. 2007. The business improvement district model: a balanced review of contemporary debates. Geography Compass, 1(4):946-958. [ Links ]

PARTNERSHIP FOR URBAN RENEWAL (PUR). 2000a. Claremont CID: Perception Survey Results. Unpublished report, CIDC. [ Links ]

PARTNERSHIP FOR URBAN RENEWAL (PUR). 2000b. Business Plan for the Establishment and Management of a City Improvement District in Claremont, Cape Town. Unpublished report, CIDC. [ Links ]

RATCLIFFE J. & FLANAGAN S. (2004) Enhancing the vitality and viability of town and city centres: the concept of the business improvement district in the context of tourism enterprise. Property Management, 22(5):377-395. [ Links ]

SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICES (SAPS). 2007. Crime in the RSA for April to March 2001/2002 to 2006/2007; Province: Western Cape; Area: West Metropole; Station: Information Management, South African Police Services. [ Links ]