Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Contemporary Management

On-line version ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.5 n.1 Meyerton 2008

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Stress management behaviour among academic employees

TFJ OosthuizenI; AD BerndtII

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Johannesburg

IIDepartment of Marketing Management, University of Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

Education is critical in the development in any country as it influences future economic growth and personal development. This education is provided by the primary and secondary, as well as the tertiary education sector, which is the focus of this paper. The recent merging of tertiary educational institutions in South Africa has affected the stress levels of employees in these institutions.

Diversity characterises the employees within a merging educational institution. Employees working under stressful conditions play a vital role in assisting the organisation to achieve its mission and objectives.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate how the academic employees (considering their diversity) of a newly-merged tertiary institution perceive their stress levels, and the stress management behaviour in individual and organisational context, to cope with these stresses. The paper examines the existing literature regarding diversity, stress and stress behaviour in organisations (specifically merging tertiary institutions).

The research was by means of a census conducted among permanent academic staff of a merged institution in South Africa. Use was made of an electronic survey in order to attract responses from the various campuses of the institution.

The findings indicate that high levels of stress are experienced by all diverse groups of academic employees, although the type of stress can be different. Management can therefore not generalise in their approach. While employees exhibit various behaviours to deal with the stress experienced, management needs to strive to provide organisational support systems in order to provide support to create an environment conducive to handling stress.

Key phrases: Stress; academic employees; stress behaviour, diversity, women, stress management

INTRODUCTION

The rate of change in organisations and their relevant business and industry environments requires employees to cope with a larger workload and the associated authority and responsibility. Various contemporary issues that can be considered in the South African context include those of diversity, stress and stress management behaviour. Increased working hours have contributed to stress in South Africa, where the average working week is 55 hours (Anon 2007:4). The tertiary education sector has also undergone a great deal of change that has in turn contributed to the stress experienced by those employed in this sector.

The paper will initially discuss diversity as a factor in an organisation. Subsequent to this, the nature of stress and the way in which academic employees manage the stresses (stress management behaviour in both a personal and organisational context) will be discussed. After this the findings relating to the survey conducted will be presented. The paper will conclude with recommendations based on the findings of the research.

LITERATURE

Diversity

Diversity is the collection of many individual differences and similarities that exist among people (Kreitner & Kinicki 2001:37). Kreitner & Kinicki's definition emphasizes three important issues about diversity in the workplace. Firstly, diversity applies to all employees, and it is not only certain arbitrary differences but all individual differences that make people unique. Therefore diversity cannot be viewed for example as only racial or religious differentiation, but as all differences combined. Secondly, the concept of diversity encompasses the differences among people as well as the similarities. The discipline of diversity requires that these two facets be considered simultaneously. Managers are expected to integrate the collective mixture of similarities and differences between workers into the organisation. Grobler (2002:46) supports this view by adding that each individual is unique, but also shares any number of environmental or biological characteristics.

According to Kreitner & Kinicki (2001:38), diversity can be described as having four layers within organisational context namely: (1) Personality - which describes the stable set of characteristics that establishes a person's identity; (2) Internal dimensions - which are characteristics that strongly influence people's attitudes, perceptions and expectations of others. These include factors such as age, race, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity and physical ability; (3) External dimensions -which are personal traits over which we can exert a certain amount of control or influence. They are factors such as income, personal and recreational habits, religion, education, work experience, appearance, marital status, and geographic location; (4) Organisational dimensions - which pertain to the organisation itself and include factors such as work field, division or unit, seniority, union affiliation, management status and functional level.

The concept of diversity can be defined in many ways. Robbins (1998) gives a broad definition and considers diversity in an organisational context as "the increasing heterogeneity of organisations with the inclusion of different groups". Considering this broad definition, it is possible to analyse the issues relating to the factors establishing diversity in an organisational context. People's observable traits (traits with which they are born), have a profound influence on their lives and can be described as fundamental to their personal identify. This is the first and fundamental component and influencing factor of diversity. These traits reflect on the way in which people perceive the world, and furthermore form the bases on which people form groups (diversity) in the organisation (Herselman 2004).

Thomas (1991) further states that factors such as work roles and positions, education, income, social responsibility, marital status, place of residence, wealth and belief system can be considered as a secondary dimension to diversity. These factors will be more likely to provide further dimension and depth to people's personality and create individuality. Because of the said factors, people will most likely join different social, union, political and religious groups. Therefore, this brings different orientations to the workplace.

The behaviour, ideas and views of people are the best sources to utilise in order to identify diversity in people regarding aspects such as their work motivation, how they integrate professionally in the work environment, their attitudes, perceptions, beliefs and behaviour regarding the work situation, their ambitions in the workplace, and their perceived official roles and duties in the organisations. These factors can be described as the tertiary factors establishing diversity (Herselman 2004). Although all these factors are identified on primary, secondary and tertiary level, under no circumstances do they indicate levels of importance.

Another aspect that needs attention in understanding diversity is the role that culture plays in forming the individual's personality, perceptions and behaviour. "Culture is the unique pattern of shared assumptions, values, and norms that shape the socialisation, symbols, language, narratives and practices of a group of people" (Hellriegel, Jackson & Slocum 2005:104). The core elements include norms and values (the basic belief that something has great importance and meaning and will be of great importance for a length of time) as well as the assumptions (underlying thoughts and feelings that people in a certain culture believe to be true and take for granted). People thus make up the hidden elements of culture. On the other hand, factors such as practices, narratives, language, symbols and socialisation can be described as the observable elements of culture.

Hofstede (2001:9-12) analysed the aspects of cultural diversity and developed a model to allow a better understanding of cultural differences. The dimensions identified in this model are: individualism (work as an individual) vs collectivism (work in teams); power distance (centralised vs decentralised power); uncertainty avoidance (taking of risk or avoiding of risk); the gender role (masculinity vs femininity) and time orientation (long term vs short term).

"Conflict can easily arise between people when working together, especially when they are not like-minded, with different ideas, views, experiences and perspectives" (Worman 2005:27). Therefore diversity should be considered when investigating the existence of stress in individuals and the way they behave in order to deal with the stress.

In the South African context, it is therefore important to consider the uniqueness of diversity as well as cultural diversity in the organisation. A variety of external factors influence how diversity evolves in social and organisational contexts in the South African organisation today. Some of these factors to be considered are: a new democracy; employment equity legislation, racial and gender equity in the workplace; increased conflict, globalisation, education and skills development, language equity and communication; financial matters and remuneration levels and disparity; social and personal problems; affirmative action, job security and social security; unethical conduct, HIV/AIDS, culture and tradition; and resource availability to mention a few (Herselman 2004; Oosthuizen 2007:35-38).

The development of these diverse employees in the South African organisation is an essential requirement to ensure future success in global participation.

Stress in the workplace

One of the key characteristics of our modern lifestyle is the rate at which everything takes place. This has the impact of increasing the stress levels experienced by individuals.

Stress is generally used to describe our negative response to everyday pressures. In general, the term stress is used to indicate a situation where people do not feel that they can cope effectively with a specific threat. This description of stress also focuses attention on the cognitive factors of stress: "Two individuals can be faced with exactly the same work situation, for example the annual appraisal, but one may see it as stressful while the other may feel totally at ease in the situation" (Newell 2002). A further definition is that stress is a condition or feeling that a person experiences when they perceive that the demands placed on them exceed the resources at their disposal (Anon n.d.). Lussier (2009:299) defines stress as "the body's reaction to environmental demands ... this reaction can be emotional and/or physical".

"Stressors are factors that cause people to feel overwhelmed by anxiety, tension and/or pressure" (Lussier 2009:299).

Stress can be described as functional or dysfunctional. Functional stress improves performance by motivating people to reach the set objectives. However, excessive stress can result in a variety of negative emotional and/or physical reactions, thus becoming dysfunctional (Lussier 2009:299). The problem of stress is not limited to certain categories of employees, certain levels in the organisation or any specific group. In the South African context, employees are subject to greater degrees of stress due to unique social conditions. Furthermore, organisations place stress on employees while seeking to satisfy political and legal requirements in order to satisfy government, equity and empowerment imperatives.

Part of coping with stress is identifying the source of the stress. Lussier (2009, 299-301), indicates that the five most common contributors to stress in the workplace are: type of work, organisational culture, personality type, interpersonal relations and management behaviour. Robbins & De Cenzo (2004) group these sources of stress in two main categories, namely workplace and personal stress.

Workplace stressors

Robbins & Coulter (1999:15) identify a number of sources of workplace-based stresses that are experienced by employees in an organisation, including:

• Role ambiguity: this means that a person (either a team member or the team leader) does not know how to perform on the job, or what the expected relationship is (i.e. the link between performance and the consequences). This can be associated with the lack of a job description for jobs.

• Role overload: this refers to having to do too many things and having too many roles to play in the work situation. The use of project management within organisations results in a team leader having to manage a department while also having to contribute to the project. Time management and allocation become a difficult task. In the case of academics, the pressure to publish in accredited publications for example is added to a teaching workload and in some cases managerial/administrative work places greater demands on academics.

• Technological advancements: things work quicker now than in the past due to technological development. This means there are greater changes that require adaptation, causing stress. There is also the stress associated with keeping up to date with new systems continually being introduced.

• Reengineering/downsizing/restructuring and associated change: this refers to the insecurity associated with possible retrenchments that accompany restructuring. This is specifically a potential threat in the case of certain tertiary institutions where mergers have taken place.

• Fear (responsibility): this refers to fear of failure in the job with respect to other people and being held responsible for the actions of others.

• Working conditions: this refers to difficult working conditions that arise from lighting, temperature or noise (and for some this may refer to the open plan offices in which they work). For academics this could be associated with larger classes, a greater administration load and the integration of different learning approaches (technikon versus a university approach).

• Working relationships: there are stresses between the people in the organisation such as between team leaders and colleagues. The causes of these stresses are varied and can include management style and communication breakdowns.

• Excessive rules and regulations in the workplace: this makes it difficult to show initiative and abiding by the rules results in stress for an employee.

• Job mismatch: this refers to the person doing the job and the skills required to carry out the task. There is a mismatch when the person's skills and the skills required in the job are not the same. This places stress on the team member, as he is conscious of his lack of skills.

• Change in an organisation also leads to employee stress. The kind of change influences the level of stress experienced by each different individual in the workplace. Hellriegel et al (2005:316) describe organisational change as "any transformation in the design and functioning of an organisation". De Frank and Ivancevich (1998) identify at least two types of change that impact on stress in organisations, namely competition and technological change.

Other sources of stress identified by De Frank and Ivancevich (1998) include: increased diversity in the workforce, employee empowerment and teamwork, and violence in the workplace.

Personal stressors

The term "personal stress" is used to describe the stress experienced by individuals based on factors that are unique to them due to their life experiences and circumstances.

• Personality type affects the nature of the stress experienced by individuals. Two main personality types have been identified with regard to the stress experienced by a person. Type A personalities are more likely to be goal driven, have an urgency to get things done and are competitive. They are impatient to get things done and struggle to cope with leisure time. They are more likely to be stressed and suffer from heart disease (Robbins & De Cenzo 2004). Type B personalities are relaxed, easygoing and non-competitive.

• Family matters such as divorce and death have been identified in research as being contributors to stress levels. Previous research has acknowledged the effect of these factors on the stress levels experienced.

• Financial problems (at home) affect the stress levels of individuals and their ability to function adequately.

• The various roles that people have to play in the various aspects of their life such as mother, father, employee, friend, etc. (Newell 2002) also influence stress.

Effects of stress in individuals

While a certain amount of stress is natural, the work situation can result in too much stress (Stanley 2008:21). The consequences of excessive stress can be seen in three main ways in the lives of employees:

• Physiological (physical health) problems

Heart disease, changes in the metabolic and breathing rates, blood pressure problems as well as headaches (migraines) and heart attacks are some of the physical conditions that are identified in people who experience high stress levels. These conditions are potentially life threatening, and impact on the quality of life (Stöppler 2005).

• Psychological problems

Psychological symptoms of stress can be seen in the negative emotions experienced by individuals, such as depression, anxiety, apathy and anger (Newell 2002). Other consequences include tension, irritability, boredom and job-related dissatisfaction (Robbins & Coulter 1999:15).

• Behavioural consequences

Behavioural effects of stress can be seen in the way in which employees act when they perceive they are under stress. Certain individuals smoke more, others suffer from insomnia while others drink more. These behaviours can serve as clues to the stress levels being experienced.

In an organisational context, it is important to understand the meaning of stress as it results in strain, and this manifestation can be psychological or physiological. In the workplace, high stress levels can be seen in absenteeism, reduced levels of productivity and the job turnover levels (Robbins & Coulter 1999:15).

The tertiary education sector as a work place in South Africa

The task of tertiary education includes providing in-depth knowledge, academic development, education of students as well as the co-ordination of national development demands (Chen, Yang, Shiau & Wang 2006:485). This implies that academics are involved with a number of major tasks, namely teaching, researching, administration and management (Ulmer et al in Chen et al 2006:485).

The tertiary education sector in South Africa is one that has undergone a great deal of change in the last five years. Mergers have taken place among a number of universities and technikons, which has contributed to stress among academic employees. One of the dangers associated with any merger is the blending of corporate culture that is required in the new merged institution. Because corporate cultures reflect the values of the employees, the changing thereof tends to be resisted by employees in both merging institutions. The clashing of these institutional cultures has resulted in increased tensions in the merging institutions (Naidoo 2004).

Various factors have been identified as impacting on the task of academics involved in higher education including the increase in class sizes (often accompanied by no increase in resources), little recognition of teaching skill, increase in the volume of marking and the demands of individual students (Oshagbemi 1997:357). A further factor which has been identified is declining quality of students in this sector (Oshagbemi 1997:358).

Stress Management behaviours

Excessive stress has been shown to have negative effects on individuals. This has resulted in the use of various stress management techniques in order to bring stress levels to "manageable levels".

There are several different stress management techniques that can be used (Anon n.d). These include:

• Action-orientated techniques: the focus of these techniques is those that enable the individuals to face the stress by giving them power to use the situation to their advantage. This also increases the resources that can be used in the situation.

• Emotionally-orientated techniques: the focus of these techniques enables the individuals to change the way they think about the stress, and as a result, change the way we think and feel about the stress. This means that we adjust our perceptions of the situation.

• Acceptance-orientated: there are certain stressful situations over which the individual has no power, such as in the case of the death of a loved-one. The focus of these techniques is thus to survive the situation as best as possible.

Lussier (2009:301-303) also proposes six general management techniques that can be used to decrease work related stress: These techniques include time management, relaxation, nutrition, exercise, positive thinking, and the creation of a support network.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Research Problem

Employees working under stressful conditions play a vital role in assisting the organisation to achieve its mission and objectives. The first question that is posed in this paper refers to the nature of the diversity in the merged organisation. The purpose of the research is to determine how the different groups of academic employees evaluate and deal with stress in an academic institution.

Research Tool

Use was made of quantitative research among permanent academic employees. As this is a pilot study, the research was only conducted among the academic staff on all the campuses of the merged institution. There are approximately 846 permanent academic employees on the various campuses of the institution.

Use was made of an instrument that was developed for the study, but this instrument was based on previously-developed instruments. There were four sections to the entire questionnaire, but only two sections are reported on in this paper and thus serve as the focus.

Section A: Diversity factors

The purpose of this section was to determine the diversity of the respondents while also collecting important information regarding their profile.

Section B: Stress evaluation and stress management behaviours

The questions posed required the respondent to indicate the degree of stress as evaluated by the respondent. Further, the respondents were asked to indicate possible ways in which they (both in a personal and in a departmental context) cope with the stresses being experienced. This enabled the researchers to determine the stress management behaviours exhibited by the respondents.

Use was made of a five point scale, from never (1) to very often/always (5).

Sampling

All academic employees were included in order to ensure that all post levels were represented, and to give as many academic employees as possible the opportunity to take part in the research. Only employees who were employed on a permanent basis were included in the research.

Data analysis

Responses were analysed using SPSS and descriptive analysis was conducted on the responses received. Further statistical testing was carried out in order to determine significances between various groups.

RESULTS

Realisation rate

A total of 230 responses were received to the electronic survey. The responses constitute 27,2% of the permanent academic employees.

Summary of the respondent profile

The respondent was most likely to be:

• Female (64,3%)

• Either in the age group 31 - 40 (25,2%) or 41 -50 years (25,7%)

• Belong to an organised religion (73,5%)

• Involved in a religious group to a moderate extent (27.4%)

• Afrikaans speaking (50.0%)

• Employed at Institution 1 prior to the merger (40,4%) or joined the institution after the merger (28,3%)

• Have an Honours degree or a more advanced qualification (57,4%)

• Married or co-habiting (61.3%)

• Not in a managerial position within the organisation (85.7%)

• Not involved in co-ordinating a programme (59.6%)

• Heterosexual in their sexual orientation (79.1%)

Findings regarding experiences of stress

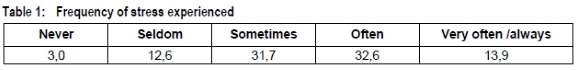

Respondents were asked to indicate how they experienced the work situation with regard to their perceived stress levels. From Table 1, it can be seen that 13,9% of respondents indicated that they experienced stress very often to always, while a further 32,6% indicated that they experienced stress often. The majority of respondents (78,2%) indicated that they do experience stress, varying from sometimes to extreme levels (always). The figures are reflected in Table 1 below, and all figures are reflected as percentages.

Further analysis indicated that there are no significant differences between the genders with regard to how often (frequency with which) stress is experienced.

Findings of the individual stress management behaviours

Based on the literature, various stress management behaviours or activities were identified that could be used by individuals during times which are perceived as stressful. These include for example socialising, shopping, and exercise. Using a five point scale, the respondents were asked to indicate how often they engaged in this behaviour.

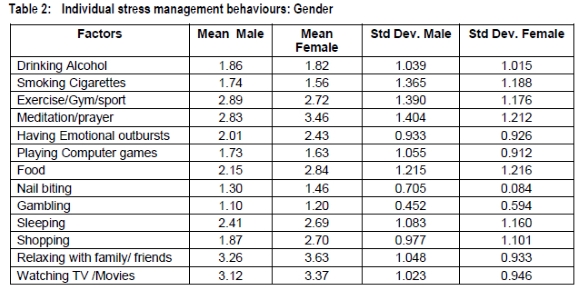

The findings show that respondents did not make use of gambling or nail biting as typical behaviour to manage stress. This is true of both genders, as can be reflected in Table 2 (mean = 1,1 and 1,2 respectively for gambling and mean = 1,3 and 1,46 for nail biting). Further analysis indicates that these responses also have a standard deviation which indicates a high degree of agreement among the respondents.

Behaviours that had the highest means among the respondents (indicating that they are done very often to always) include relaxing with family and friends and watching TV/movies. Breaking these down according to the specific genders reflect similar responses from both genders: men vs women (mean = 3,26 and 3,63 respectively for relaxing with family and friends and mean = 3,12 and 3,37 respectively for watching TV/movies).

Further analysis of the mean scores according to the gender of the respondents shows higher mean scores among female respondents with regard to meditation/prayer (mean female = 3,46), food (mean female = 2,84), and shopping (mean female = 2,70). Detailed findings are reflected in Table 2.

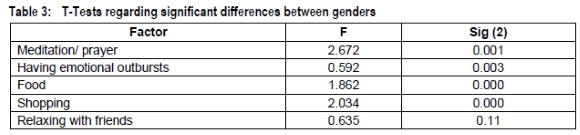

Further analysis using a Two-Sample t-Test indicates that the differences between the gender groups is significant with respect to the use of meditation/prayer (p = 0.001), having emotional outbursts (p = 0.003), food (p = 0.000) and shopping (p = 0.000). Despite relaxing with family and friends having the highest means among both genders, the difference between the groups is statistically significant (p = 0.11), where significance is reflected where p < 0,05. The findings are presented in Table 3.

Findings regarding stress management behaviours in an organisational context

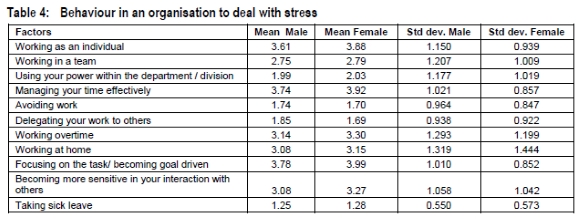

From literature, several stress management behaviours were identified that are used in order to cope with stress in an organisational context. From the responses received from men and women, the behaviour that is never undertaken is the taking of sick leave (mean = 1,25 and 1,28 respectively) and the avoidance of work (mean = 1,74 and 1,70 respectively). Further analysis of these responses indicates a high degree of agreement among the respondents (as seen in the standard deviations associated with these responses).

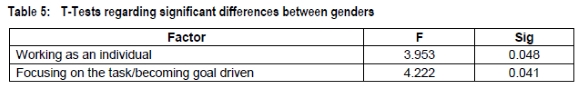

Stress management behaviours that have the highest means are those of "working as an individual" (mean = 3,61 and 3,88 respectively) and "focusing on the task/becoming more goal driven" (mean = 3,78 and 3,99) and managing your time effectively (mean = 3,74 and 3,92 respectively).

Little difference in the mean scores can be observed between the male and female respondents. The findings are reflected in Table 4.

Further analysis using a two-sample t-test indicates that the differences between the gender groups is significant with respect to "working as an individual" (p = 0,048) and "focusing on the task/becoming more goal driven" (p = 0,041). These are significant as the p values are less than 0,05.

LIMITATIONS OF THE RESEARCH

There are potentially a number of limitations associated with the study that need to be addressed. Firstly the study was conducted in a newly-merged institution, meaning that it may not be possible to generalise the findings to other institutions and to academics in these institutions. Secondly, with the institution being in a metropolitan area, the findings can not be assumed to be general to institutions in other geographical areas. Thirdly, the study did not attempt to control for stresses experienced in the environment (such as crime or economic pressures), which may have had an impact on the responses received. The research does not aim to measure stress but to establish how people behave under conditions of stress.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a high degree of perceived stress among academic employees, both male and female. While both groups experience stress, these two diverse groups do have similarities and differences in the behaviours they exhibit to manage these stresses. Considering individual activities, both men and women will consider time with family and friends as valuable in order to manage stress. This is further supported with both genders considering the watching of TV/Movies as an alternative behaviour (which can be shared with others) to manage their stress. Considering these two facts, it indicates that both men and women have a high social need. A work environment that does not allow for socialisation (time at work (teams) or time at home (family and friends)), will negatively impact on these employees' abilities to manage their stress on an individual basis.

The general differences between men and women are reflected in the following behaviour: eating of food, shopping and meditation/prayer. Women consider these three behaviours more strongly than men, in order to manage their stress on an individual basis. Academic organisations would therefore need to be sensitive for female staff's needs especially in terms of spirituality, but also in terms of accessibility to food and time for shopping.

In an organisational context, similarities between men and women are established in terms of employee loyalty. This is indicated by both men and women not considering work avoidance or the regular use of sick leave in order to manage stress at the office. These behaviours are supportive of an organisational culture but can have a variety of long term effects for individuals. Furthermore both genders consider using time management, management by objectives (task orientation), and individual performance to manage stress in their work place. The differences between male and female academics in the organisational context are in terms of performance as an individual as well as their task orientation or management by objectives.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

While there are differences, there is also a high degree of similarity with regard to the behaviours exhibited by the gender groups. Management of academic institutions needs to take cognisance of the stress levels experienced by academic staff.

High levels of stress are experienced by all diverse groups of academic employees, although the type of stress can be different. Management can therefore not generalise in their approach.

Dominant personal activities to deal with stress are: meditation/prayer (spirituality); watching TV/movies; and relaxation with family and friends. Opportunity must be provided to all employees in terms of, for example, working hours and a spiritual-conscious work environment.

Dominant behaviours to deal with stress in an organisation are: working as an individual; managing time; and task orientation (goal driven). These behaviours are not necessarily ideal as they reflect the perception of unique groups. Skill development can enhance academic staff's ability to: improve time management skills; develop performance measurement systems for measuring individual performance; and create a balanced people- and task-orientation, acknowledging a balanced management by objectives approach. An academic culture of professionalism is required, although it is necessary to consider a balanced approach where stress is minimised and not maximised. A developed and enhanced work environment with the necessary supportive staff and systems will further address the current levels of stress.

The strong need for meditation/prayer and socialisation with family and friends indicates specific needs of employees. A work environment supportive of this is crucial.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANON. 2007. Work stress has risen in SA. The Star, 30 May: 4. [ Links ]

ANON N.D. Introducing Stress Management. from http://www.mindtools.com; downloaded 20-03-2008. [ Links ]

CHEN S.H., YANG C.C., SHIAU J-Y. & WANG H.H. 2006. The development of an employee satisfaction model for higher education. The TQM Magazine, 18 5):484-500. [ Links ]

DE FRANK R.S. & IVANCEVICH J.M. Aug 1998. The Academy of Management Executive. Briarcliff Manor, 12(3):55. [ Links ]

GROBLER P.A. 2002. Human Resource Management in South Africa. London: Thomson Learning. [ Links ]

HELLRIEGEL D., JACKSON S.E. & SLOCUM J.W. 2005. Management: a competency-based approach. 10th Edition. USA: South Western Thomson Learning. [ Links ]

HERSELMAN S. 2004. Dynamics of diversity in an organisational environment. Pretoria: Unisa Press. [ Links ]

HOFSTEDE G. 2001. Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviours, institutions and organisations across nations. 2nd Edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

KREITNER R. & KINICKI A. 2001. Organisational Behaviour. 5th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

LUSSIER R.N. 2009. Management fundamentals: concepts, applications and skill development. 4th Edition. Springfield: South-Western. [ Links ]

NAIDOO P. 2004. Painful progress but real test lies ahead. From http://secure.financialmail.co.za; downloaded on 04-07-2005. [ Links ]

NEWELL S. 2002. Creating the healthy organisation: well-being, diversity and ethics at work. USA: Thomson Learning. [ Links ]

OOSTHUIZEN T.F.J. 2007. Management tasks for managerial success. 3rd ed. Johannesburg: FVBC. [ Links ]

OSHAGBEMI T. 1997. Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in higher education. Education & Training, 39(9): 354-359. [ Links ]

ROBBINS S.P. 1998. Organisational behaviour. Upper Saddle-River: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

ROBBINS S.P. & COULTER M. 1999. Management. 6th Edition. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

ROBBINS S.P. & DE CENZO D.A. 2004. Fundamentals of Management - Essential concepts and applications. 4th Edition. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

STANLEY T.L. 2008. Control your job stress. The American Salesman, 51(3):20-24. [ Links ]

STÖPPLER M. 2005. Job Stress Can Raise Blood Pressure. From http://stress.about.com; downloaded on 29-06-2005. [ Links ]

THOMAS R. 1991. Beyond race and gender: unleashing the power of your total work force by managing diversity. New York: American Management Association. [ Links ]

WORMAN D. 2005. Personnel today. Sutton. 17 May:27. [ Links ]