Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.5 no.1 Meyerton 2008

RESEARCH ARTICLES

What future subordinates will value in their leaders: an exploratory study

A CoxI; T AmosI; J BaxterII

IDepartment of Management, Rhodes University

IIDepartment of Statistics, Rhodes University

ABSTRACT

Leaders should not randomly choose a leadership style. To be effective, leaders need to ensure that their leadership style is congruent with what subordinates value. The focus of this study is on what the future South African graduate workforce will value in a leader. The female and male respondents in this study emphasise similar leadership values, indicating that there is no distinct set of competencies that will be valued separately by males and females. The same was found for respondents of different cultures, namely African, Coloured, Indian, White and other. With respect to both gender and culture, the respondents emphasise a mixture of African and Western leadership values. This supports the idea that to be effective in South Africa, leaders need to understand the prevailing national cultural values before simply applying "foreign" leadership models and theories based upon cultural values found in the West. This research finds that irrespective of gender and culture in the South African workplace, to be effective, leaders need to be loyal and inspirational, have vision and integrity and must be open and honest with their subordinates. Leaders should avoid being autocratic, strict, religious, ritualistic and traditional. They should also avoid using consensus and perceived external control.

Key phrases: Leadership values, African, Western, gender, culture

INTRODUCTION

In an increasingly competitive global and national economic environment, the competitive advantage of an organisation no longer lies in its products or technology, but in its human resources. It is the job of managers to realise this competitive advantage by influencing human resources to contribute their best in line with the strategic goals of the organisation. To achieve this, managers need to not only demonstrate leadership but effective leadership.

To be effective, leaders need to ensure that their style is congruent with what subordinates value in leaders. This is complicated in the African context by the diversity of tribal and racial cultural values (Mbigi 1993) which can influence what is valued in leaders. Values are not only influenced by the culture of subordinates but also by gender (Rigg & Sparrow 1994; Rozier & Hersh-Cochran 1996; House & Aditya 1997; House et al 1997; Booysen 2001).

The challenge for managers in the South African context is to understand and respond to what a diverse workforce, in terms of racial cultures and gender, value in their leaders. In addition, with evidence showing that Western leadership practice and theory are not universal (Adler 1991), there is a need to also explore the applicability of Western leadership in an African context.

The purpose of this research is to identify what future graduates in South Africa of different genders and diverse racial cultures will value in their leaders when they are in the workplace. The future graduate is defined as a third year or postgraduate student registered at a South African university and is categorised in terms of diversity according to their gender and racial culture. For purposes of the research gender is defined as male and female while culture is defined in terms of racial cultural groups: African (black), Coloured, White, Indian and Other (for example Chinese).

The value of this research lies in its focus on future subordinates of diverse genders and cultures. In addition to identifying what they will value in their leaders, the research will also identify whether subordinates emphasise Western or African values. This will provide input into the debate concerning the applicability of Western leadership values in the South African context. The research will also describe the components of effective leadership relevant to the South African context and so assist both local and international leaders in being effective in South Africa. The research will serve as input for those involved in the design and delivery of Master of Business Administration (MBA) programmes and general leadership development both locally and internationally.

The goals of the study are:

• To identify what male and female subordinates value most and least in their leaders.

• To determine whether the values emphasised by males and females are African or Western in nature.

• To identify what subordinates of different cultures value most and least in their leaders.

• To determine whether the values emphasised by respondents of different cultures are African or Western in nature.

• To identify the leadership values influenced by gender.

• To identify the leadership values influenced by culture.

• To describe the leadership required to be congruent with what graduates about to enter the South African workplace value in leaders.

• To test the reliability of the research instrument.

LEADERSHIP, GENDER AND CULTURE

A common theme among the many different definitions of leadership is the relationship between leaders and their subordinates. This relationship is more effective if there is congruence between the leadership exhibited by leaders and the leadership values emphasised by subordinates. A misalignment of fit between what subordinates value in leaders and the leadership of the subordinates will result in the leader being ineffective (Hofstede 1980; Mellahi 2000; Mastrangelo et al 2004).

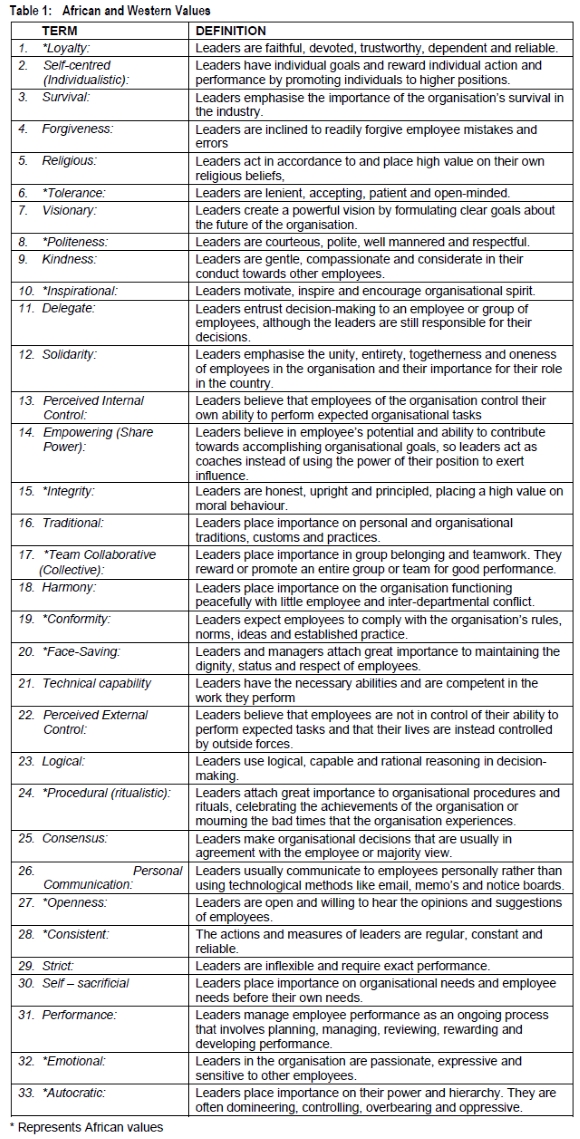

What subordinates value in leaders can be understood in terms of the African and Western leadership values identified and defined by Salomon & Khabisi (2004) in table 1.

Evident in the literature is support for gender (Cann & Siegfried 1987; Brownell 1994; Kent & Moss 1994; Chang & Chang-McBride 1997) and culture (House & Aditya 1997; House et al 1997; Brodbeck 2000; Booysen 2001; Littrell & Nkomo 2005) influencing what subordinates value in leaders. For instance, women are said to value a leader who is considerate, follows a transformational leadership style and is participative and people-oriented (Claes 1999). Besides integrity and loyalty men are said to value leaders who are autocratic, business oriented and transactional in their approach (Brownell 1994; Claes 1999; Kawakami et al 2000). A gender-centred model (Lewis & Fagenson-Eland 1998) that highlights masculine and feminine tendencies indicates that there are psychological differences between men and women, which result in them favouring different leadership values. This model indicates that men prefer task-oriented behaviours whereas women prefer relationship-oriented behaviours (Hammick & Acker 1998; Lewis & Fagenson-Eland 1998).

Literature on culture though, for example Hofstede (1991) tends to make broad reference to Western and African cultures without considering the diversity of tribal and racial cultures in South Africa.

In contrast to the argument for differences between what subordinates of different genders and cultures value in leaders, there is literature, for example Littrell & Nkomo (2005) that argues for no differences in what subordinate's value in a leader based on gender and/or culture.

In spite of the diversity of gender, tribal and racial cultural values South African leadership is said to be both rigid and authoritarian (Choudhry 1986), described as autocratic, hierarchical and individualistic whereby decisions are rarely discussed with one's subordinates, resulting in a top-down communication system (Ocholla 2002).

Prime (1999) identifies three approaches to describe the leadership adopted by leaders in South Africa. Firstly Western leadership, which is consistent with the Western value systems, is based on individualism, self-centredness and competition (Prime 1999). Secondly Afrocentric leadership, which is founded on the belief that the authority of the leader is assumed to be right and results in subordinates having to show respect and obedience to their superiors (Mellahi 2000). It is guided by certain basic, traditional values and principles and emphasises traditionalism, communalism and cooperative teamwork (Nzelibe 1986). Ubuntu has played a critical part in Afrocentric leadership, which is categorised by five core competencies, specifically survival, solidarity, spirit, respect and dignity (Khoza 1993; Mbigi 1997; Booysen 1999; Bekker 2006). The last approach is synergistic inspirational leadership, more commonly known as dualistic leadership whereby traditional African leadership practices, values and philosophies are integrated with Western leadership practices, values and philosophies (Prime 1999).

METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted on a convenient sample (Leedy 1993) of future graduates registered at two South African universities in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. For purposes of the research a future graduate is defined as a third year or postgraduate student registered at a South African University. Postgraduate students are defined as postgraduate diploma, honours, masters and PhD students.

The population consisted of a total of 1 347 students. This total comprised 681 third year and 303 postgraduate students registered in the Commerce faculty at the one University and 310 third year and 53 post-graduate students registered in the Management Department at the other University.

The data was collected using the survey method (Van der Stede et al 2005), through the application of a questionnaire to the sample. The questionnaire is based on one originally developed by Salomon & Khabisi (2004) which includes thirty-three items of Western and African leadership values (see table 1). In spite of the questionnaire being used previously in two South African studies (Salamon & Khabisi 2004; Brownell & Cox 2005) there are no reported results of any reliability tests.

The questionnaire was adapted for purposes of this study and pilot tested on faculty members and students who were not part of the study. The final version of the questionnaire consisted of the original thirty-three items and also made provision to capture relevant biographical information (gender, culture and university). Respondents were asked to rate each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from "no value" to "strong value" in terms of the question: "Rate the extent to which you will value each term in your leader, once you are in the workplace?"

The data collection process began by gaining permission from the two institutions to conduct the research. Over a period of five weeks, the researcher, with the help of an assistant, attended approximately 23 tutorial/lecture sessions at the one university to collect the data. The students present in the sessions were given the opportunity to complete the questionnaire and the researcher was available to answer any queries and collect the questionnaire upon completion. If a respondent had already completed the questionnaire in a previous session, they were told not to complete the questionnaire again. Postgraduate students who do not meet regularly in a tutorial/lecture session were given questionnaires to complete in their own time and arrangements were made to collect the completed questionnaires. At the other university, the researcher administered the questionnaire during a class session and was hence present to answer queries and collected the completed questionnaires.

Once the data was collected, each questionnaire was numbered and captured in a MicroSoft excel document and imported into Statistica Version 7 (Statsoft 2004). The data was described using frequency tables and histograms and the instrument's reliability was tested using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The overall mean scores and ranking of leadership values were produced. For purposes of the research, the top and bottom ten values are identified as the most and least important respectively. Pearson's chi-square test was utilised to test whether there is a relationship between the leadership values and the variables of gender and culture.

RESULTS

The total number of respondents in this study was 683, a response rate of 63%. Females accounted for 45% (306) of the respondents and males 55% (377) while 5% (37) identified themselves as Indian, 46% (315) African, 41% (279) White, 5% (32) Coloured and 3% (20) Other.

Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated for each scale of the questionnaire as well as for each category of leadership values, namely African and Western. Cronbach's alpha coefficient score for Western values was 0.691726, which is satisfactory and 0.757040 for African values which is good (Nunally 1978; Sekaran 1992). The research instrument was consequently taken to be reliable for purposes of the study.

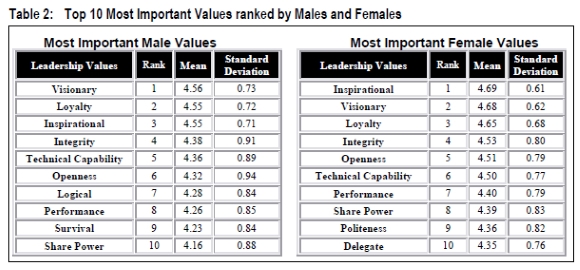

Table 2 identifies the top ten values regarded by male and female respondents as most important. It is evident from table 2 that males and females both emphasise visionary, loyalty, inspirational, integrity, technical capability, openness, performance and share power amongst their most important leadership values. Of these, four represent African values, namely loyalty, inspirational, integrity and openness while the rest can be described as Western values. The values not shared by males and females as amongst the ten most important are logical, survival, politeness and delegate with males emphasising logical and survival and females politeness and delegate.

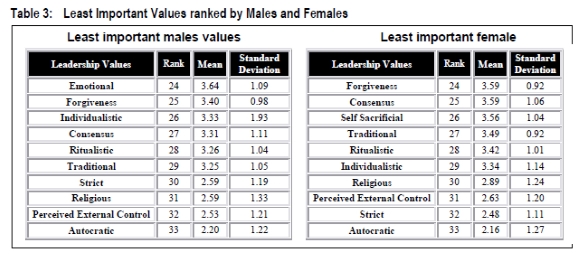

Table 3 provides the ten least important values ranked by both males and females. The values identified by both males and females as least important are forgiveness, individualistic, consensus, ritualistic, traditional, strict, religious, perceived external control and autocratic. However, males include emotional amongst their least important while females include self-sacrificial. The nine values shared by both male and female respondents as least important are predominantly Western values, except for two African values, namely ritualistic and autocratic.

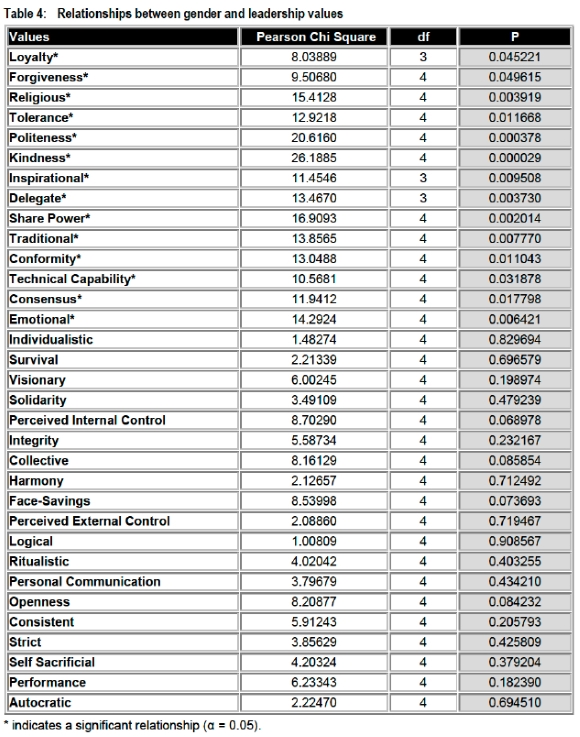

Table 4 presents the results of Pearson's chi-square tests of the relationship between leadership values and gender. Marked values indicate a significant relationship between the specific leadership value and gender.

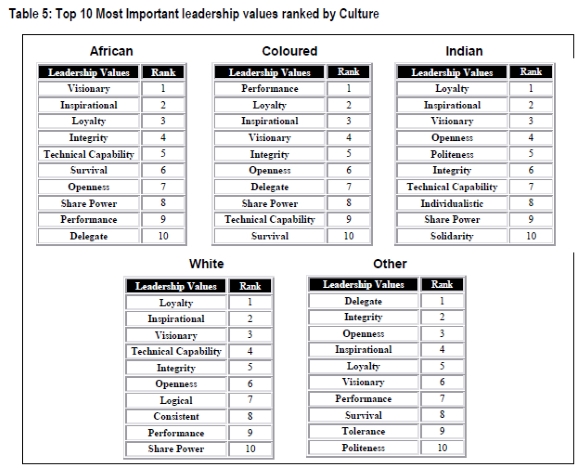

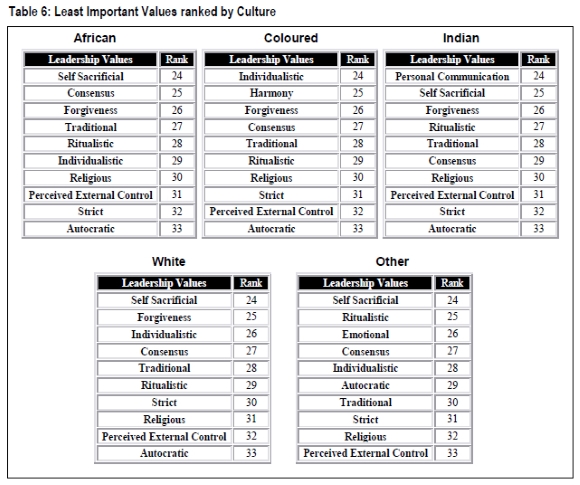

The leadership values listed as the most (table 5) and the least important (table 6) according to culture clearly indicate that the rankings are fairly similar in that the leadership values may not be in the same order, but generally the list contains the same values for all the cultural groups, especially the least important values.

It is evident from the table 5 that five out of the ten values ranked as the most important are the same across all cultural groups, namely visionary, inspirational, loyalty, integrity and openness. Of these, inspirational, loyalty, integrity and openness represent African values. These four values are the same four African values emphasised by both males and females as amongst their top ten values.

Technical capability and share power were also ranked in the top ten most important values for all cultural groups except for the group categorised as 'Other', where technical capability was ranked as 19th and share power ranked as 17th. Performance was also ranked in the top ten most important values for all cultural groups except for Indian respondents who ranked performance as 11th on their list of importance.

It is evident in Table 6 that seven of the ten values ranked as the least important are the same for all cultures. These values are consensus, traditional, ritualistic, religious, perceived external control, strict and autocratic. These are mostly Western values, except for two African values namely, ritualistic and autocratic. Self-sacrificial was ranked amongst the ten least important values for all cultural groups except by Coloured respondents, where it was ranked 20th. Individualistic was also ranked amongst the ten least important for all cultures except the Indian respondents who ranked individualistic as amongst the top ten most important as 8th. Also, forgiveness was ranked in the top ten most important values for all cultural groups except by the cultural group categorised as 'Other', were it was ranked as 18th.

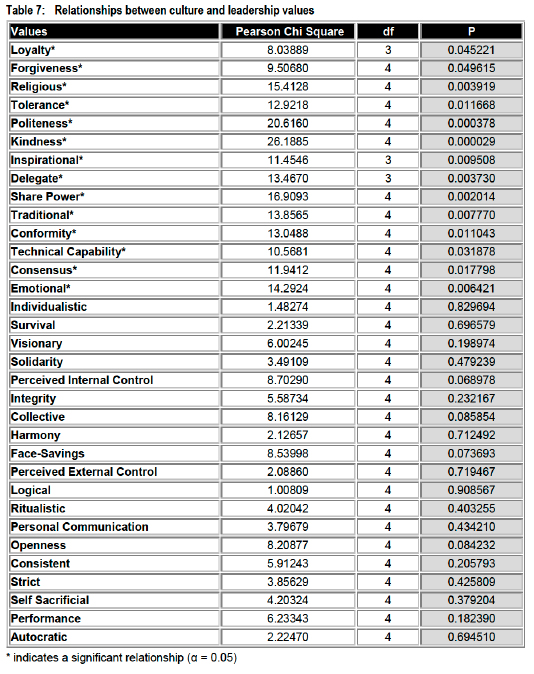

Table 7 presents the results of Pearson's chi-square tests of the relationship between leadership values and culture. Marked values indicate a significant relationship between the relevant leadership value and culture.

DISCUSSION

This study found both male and female groups to emphasise visionary, loyalty, inspirational, integrity, technical capability, openness, performance and share power amongst their ten most important leadership values (table 5) and forgiveness, individualistic, consensus, ritualistic, traditional, strict, religious, perceived external control and autocratic amongst their ten least important values (table 6). Overall, these findings show that in accordance with literature (Littrell & Nkomo 2005), there are more similarities in what males and females do and don't value in their leaders, than there are differences. Of the values emphasised by both males and females, four represent African values, namely loyalty, inspirational, integrity and openness while the other four are Western values. This points to an emphasis on a mixture of both Western and African values, implying that a synergistic inspirational/dualistic leadership approach would be appropriate (Prime 1999).

The rankings of the leadership values according to gender do not support literature (Lewis & Fagenson-Eland 1998; Rigg & Sparrow 1994; Rozier & Hersh-Cochran 1996; House & Aditya 1997; House et al 1997; Booysen 2001) that proposes considerable differences in what subordinates value in their leaders across gender groups. Nor does it support previous research (Hammick & Acker 1998; Lewis & Fagenson-Eland 1998) suggesting that men prefer task-oriented behaviours whereas women prefer relationship-oriented behaviours or literature (Brownell 1994; Claes 1999; Kawakami et al 2000) that proposes that males usually value leaders who are autocratic, business-oriented and transactional in their approach. Some values that are described as business oriented are individualistic, conformity and autocratic. From Table 3 it can be seen that males rank both individualistic and autocratic as their least important leadership values, with autocratic in fact ranked as the least important of all the leadership values.

Significant relationships were found between 14 of the 33 (approximately 42%) leadership values and gender (table 4). When analysing the leadership values emphasised by both male and female subordinates amongst the ten most important with the results of the Pearson's chi-square tests, it is evident that four of the eight values, loyalty, inspirational, technical capability and share power, are significantly (p < 0.05) related to gender while the other four, visionary, integrity, openness and performance are not significantly (p > 0.05) related to gender. Leadership values in the least important category which are significantly related to gender are forgiveness, consensus, traditional and religious while the other leadership values such as individualistic, ritualistic, strict, perceived external control and autocratic, are not significantly related to gender.

Arguments for a difference in what subordinates of different cultures value in a leader (House & Aditya 1997; House et al 1997; Booysen 2001) as well as arguments that there are leadership values endorsed across culture (Littrell & Nkomo 2005) can be found in the literature.

Five of the top ten (visionary, inspirational, loyalty, integrity and openness) and seven (consensus, traditional, ritualistic, religious, perceived external control, strict and autocratic) of the least important leadership values had a significant relationship with culture. Of the 33 values relevant to this study, 19 had significant relationships with culture (approximately 57%). Of the leadership values emphasised by all cultural groups as amongst the top ten, inspirational, loyalty, integrity and openness represent African values which are the same four African values emphasised by both males and females as amongst their top ten values.

When analysing the leadership values emphasised by respondents of different cultural groupings as the ten most important with the results of the Pearson's chi-square test of the relationship between leadership values and culture, it is evident that the values listed in the top ten most important such as visionary, inspirational and integrity are significantly (p < 0.05) related to culture while loyalty and openness are not significantly (p > 0.05) related to culture. This implies that these leadership values of loyalty and openness are emphasised as amongst the top ten most important values regardless of the culture of respondents. These two are African values. Least important values endorsed across culture include collective, consensus and strict.

If one compares the findings of this research to the South African leadership which is said to be both rigid and authoritarian (Choudhry 1986), described as autocratic, hierarchical and individualistic whereby decisions are rarely discussed with one's subordinates, resulting in a top-down communication system (Ocholla 2002), it is evident that there is a need for change. The findings of the research would suggest the need for what Prime (1999) calls synergistic inspirational leadership, which is dualistic leadership whereby traditional African leadership practices, values and philosophies are integrated with Western leadership practices, values and philosophies.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGERS

To be effective, leaders need to be aware not only of what their subordinates' value in leaders but also aware of their own leadership and be able to work towards aligning their leadership with what subordinates value. In addition, within a global context, leaders need to be prepared to operate across national boundaries and be sensitive to what subordinates of different cultures expect of leaders and to be flexible in their approach.

Leaders in the South African workplace are operating in an extremely diverse workforce. Focussing on two elements of diversity, the purpose of this research was to identify what future graduates will value in their leaders when they enter the workplace. Evident from this study is that males and females rank similar values as most and least important. The same was found for respondents of different cultures, namely African, Coloured, Indian, White and other. In addition, it was found that the variables of gender influences 14 of the 33 values studies and culture influences 19 of the 33. Of the ten most important values ranked by both males and females, loyalty, inspirational, technical capability and share power are significantly related to gender while of the ten most important ranked by the different cultural groupings visionary, inspirational and integrity are significantly related to culture.

This study demonstrates that even though South African organisations are diverse in terms of their subordinates comprising mixed gender and diverse culture, to be effective in the South African workplace in the future, leaders need be loyal, have integrity, show openness and be visionary and inspirational. These are mostly African values, except for visionary which is Western, hence the need to be follow what Prime (1999) calls synergistic inspirational leadership, whereby traditional African leadership practices, values and philosophies are integrated with Western leadership practices, values and philosophies. A loyal leader is one who is faithful, devoted, trustworthy and reliable and a leader who has integrity is honest, upright and principled. Leaders who are open are willing to hear the opinions suggested by their subordinates those who have vision are able to formulate clear goals about the future of the organisation. Additionally, leaders who are inspirational have the ability to motivate and inspire organisational spirit among their subordinates. Gender does not influence the values of loyalty and openness and culture does not influence visionary, integrity and openness.

If a misalignment of fit between what subordinates value and the leadership of leaders will result in the leader being ineffective (Mastrangelo et al 2004), then in South Africa leaders who are autocratic and strict, use consensus and perceived external control and are religious, ritualistic and traditional will be regarded as ineffective. An autocratic leader is domineering and controlling and those who are strict have been found to be inflexible regarding exact performance. Leaders who consider consensus and perceive external control take the majority view suggested by the subordinates and believe that subordinates are not in control as their lives are controlled by external factors. Additionally, leaders who are religious, ritualistic and traditional place high value on their own beliefs, organisational procedures, rituals, traditions, customs and practices.

A limitation of this study is that it focussed only on students from two South African Universities. Future research should include Universities throughout South Africa and Africa, to obtain a more representative sample.

Extensive research into what subordinates value in a leader and the actual values currently espoused by leaders would be of great use to leaders in the South African workplace. It would also assist expatriate managers within multinational organisations in that they could better understand what subordinates within a South African context would expect of them. There is an additional need for research to include organisational culture as an influencing variable.

The teaching of Western leadership theories and models in a South African context has been criticised (Khoza 1993; Mellahi 2000) yet the results from this study do not support an outright rejection of Western leadership values. Further research should be conducted to explore this observation. On a larger scale, gender and cultural research should compare what is valued in Africa, compared to the East and the West. This would be a valuable contribution to the universalistic and non-universalistic approach to leadership and add empirical input to the debate concerning the teaching of Western leadership theories in South Africa. In addition, within Africa, a comparison of South, East, North and West Africa would add empirical support to the debate of whether there is a universal African leadership style. It would also provide empirical support for the current mostly philosophical literature on African Leadership and a more in-depth and empirical base to understanding the leadership relevant to the philosophy of Ubuntu. Finally, although Salomon & Khabisi (2004) have conducted initial exploratory research into the congruence between the values emphasised in two South African MBA programmes the values MBA students believe should be emphasised in organisations, there is a need for additional research into the teaching of leadership on South African MBA programmes, which are described as the "nursery for organisational leadership" (Berry 1997).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ADLER N.J. 1991. International Dimensions of Organizational Behaviour. Second Edition. California: Wadsworth. [ Links ]

BEKKER C.J. 2006. Finding the 'other' in African Christian Leadership: Ubuntu, kenosis and mutuality. International Conference on Value-based Leadership. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch Business School. [ Links ]

BERRY A.J. 1997. Approaching the millennium: transforming leadership education for stewardship of the planet's resources", Leadership and Organization Development Journal, Vol.67, No. 5: 635-685. [ Links ]

BOOYSEN A.E. 1999. Towards more feminine business leadership for the 21st century: A literature review and a study of the potential implications for South Africa. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 23(1):31-54. [ Links ]

BOOYSEN L. 2001. The duality of South African leadership: Afrocentric or Eurocentric. South African Journal of Labour Relations, 25(3): 36-64. [ Links ]

BRODBECK F.C. 2000. Cultural variation of leadership prototypes across 22 European countries. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 73(1):1-29. [ Links ]

BROWNELL J. 1994. Personality and career development: a study of gender differences. Cornell, Hotel and Restaurant Administrative Quarterly, 35(2):36-43. [ Links ]

BROWNELL M. & COX A. 2005. Leadership Values Across Western and African Culture Paradigm: An Exploratory Study. Unpublished Honours Thesis. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. [ Links ]

CANN A. & SIEGFRIED W.D. 1987. Sex stereotypes and leadership role. Sex Roles, 17(7/8):401-408. [ Links ]

CHANG L. & CHANG-MCBRIDE C. 1997. Self-and-peer-ratings of female and male roles and attributes. Journal of Social Psychology, 137(4):527-529. [ Links ]

CHOUDURY A.M. 1986. The community concept of business: a critique. International Studies in Management and Organisation, 16(2): 79-95. [ Links ]

CLAES M.T. 1999. Women, men and management styles. International Labour Review, 138(4):431-446. [ Links ]

HAMMICK M. & ACKER S. 1998. Undergraduate research supervision: a gender analysis. Studies in Higher Education, 23(3):335-347. [ Links ]

HOFSTEDE G. 1980. Motivation, leadership, and organisation. Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1):42-63. [ Links ]

HOFSTEDE G. 1991. Culture and Organizations: Software of the Mind. England: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

HOUSE R.J. & ADITYA R.N. 1997. The social scientific study of leadership: Quo vadis? Journal of Management, 23(3):409-473. [ Links ]

HOUSE R.J., WRIGHT N. & ADITYA R.N. 1997. "Cross cultural research on organisational leadership: a critical analysis and a proposed theory", in Early, P.C. and Erez, M. (Eds.). New Perspectives on International Industrial and Organisational Psychology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

KAWAKAMI C., WHITE J.B. & LANGER E. 2000. Mindful and masculine: Freeing women leaders from the constraints of gender roles. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1):49-63. [ Links ]

KENT R.L. & MOSS S.E. 1994. Effects of sex and gender role on leader emergence. Academy of Management Journal, 37(5):1335-1346. [ Links ]

KHOZA R. 1993. "The need for an Afrocentric management approach", in Christie, P., Lessem, R. and Mbigi, L. (Eds.). African Management: Philosophies, Concepts and Applications. Randburg: Knowledge Resources. [ Links ]

LEEDY P.D. 1993. 5th Edition. Practical research Planning and Design. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. [ Links ]

LEWIS A.E. & FAGENSON-ELAND E.A. 1998. The influence of gender and organization level on perceptions of leadership behaviors: a self and supervisor comparison. Sex Roles, 39(5/6):479-502. [ Links ]

LITTRELL R.F. & NKOMO S.M. 2005. Gender and race differences in leader behaviour preferences in South Africa. Women in Management Review, 20(8):562-580. [ Links ]

MASTRANGELO A., EDDY E.R. & LORENZET S.T. 2004. The importance of personal and professional leadership. The Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 25(5):435:451. [ Links ]

MBIGI L. 1993. "The spirit of African management", in Christie, P., Lessem, R. and Lovemore, M. (Eds.). African Management: Philosophies, Concepts and Applications. Randburg: Knowledge Resources. [ Links ]

MBIGI L. 1997. Ubuntu: The African Dream in Management. Johannesburg: Knowledge Resources. [ Links ]

MELLAHI K. 2000. The teaching of leadership on UK MBA programmes. A critical analysis from an international perspective. Journal of Management Development, 19(4): 297-308. [ Links ]

NUNALLY J.C. 1978. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

NZELIBE C.O. 1986. The evolution of African management thought. International Studies of Management and Organization, 16(2):6-16. [ Links ]

OCHOLLA D.N. 2002. Diversity in the library and information workplace: a South African perspective. Library Management, 23(1/2):59-67. [ Links ]

PRIME N. 1999. Cross-cultural management in South Africa: problems, obstacles, and solutions in companies. [Internet: www.marketing.byu.edu/htmopages/ccrs/proceedings99/prime.htm; downloaded on 2006-06-29. [ Links ]]

RIGG C. & SPARROW J. 1994. Gender, diversity and working styles. Women Management Review, 9(1):9-16. [ Links ]

ROZIER C & HERSH-COCHRAN M. 1996. Gender differences in managerial characteristics in a female-dominated health profession. Health Care Supervisor, 14(4):57-70. [ Links ]

SALOMAN C & KHABISI S. 2004. Leadership Values in South African Business: Expectations of MBA Students. Unpublished Honours Thesis. Grahamstown: Rhodes University. [ Links ]

SEKARAN U. 1992. 2nd Edition. Research Methods for Business: A Skills Building Approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

STATSOFT INC. 2004. Electronic textbook: Basic Statistics. [Internet: www.statsoft.com/textbook/stbasic.html#index; downloaded on 2006-08-30. [ Links ]]

VAN DER STEDE W.A., YOUNG M.S. & CHEN C.X. 2005. Assessing the quality of evidence in empirical management accounting research: The case of survey studies. Accounting and Organizations & Society, 30(7/8):655-684. [ Links ]