Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.3 no.1 Meyerton 2006

RESEARCH ARTICLES

South African micro entrepreneurs and resources to overcome entry barriers

KP Haasje

Graduate School of Business, University of Cape Town

ABSTRACT

Since the demise of Apartheid, much governmental effort has been put into the empowerment of historically disadvantaged micro entrepreneurs in South Africa. This has resulted in the Small Business Act of 1996 and the establishment of Ntsika, a government agency that is responsible for implementing empowerment polices directed at historically disadvantaged entrepreneurs. At the time, an ongoing restructuring of Ntsika takes place and SEDA is founded as the new implementing government organisation that is going to replace Ntsika and will be responsible for all policies that are to directed at entrepreneurs. While much research is being done on this subject, there is still ambiguity on the demand for support of micro entrepreneurs. This paper contributes to the understanding of the relation between micro enterprises, entry barriers, government support and resources from a resource based view. It builds on the concept of stretching resources (Hamel & Prahalad 1993). It defines a number of key resources that are needed to overcome entry barriers that are faced by micro entrepreneurs. Two case descriptions from the Cape Town Area provide a practical application of this framework. Adding to the understanding of micro enterprise start up, this paper also will clarify the specific need for support for micro entrepreneurs.

Key phrases: micro entrepreneurship, resources, South Africa, entry barriers, support:.

1 INTRODUCTION

Africa is sometimes referred to as the lost continent. Sub-Saharan Africa is dwelling in corruption and there is poverty amongst ordinary people. Still, there is a difference between the Republic of South Africa and other southern African countries because the economy of South Africa is one of the strongest in the continent. However, South Africa has a large number of unemployed (Orford et al. 2004:14). Most of these unemployed are black, coloured and Indian individuals that were disadvantaged by the Apartheid regime. They are commonly referred to as Historically Disadvantaged Individuals (HDI's). Starting businesses provide society with the necessary economic activity (Porter 1990:125). Most of the Sub-Saharan countries call for entrepreneurship for it should bring, under certain conditions, a solution to unemployment and faster economic growth (Nafukho 1998:100).

This study will focus on the Republic of South Africa. The South African economy has grown with 3% per year, since the political change of the mid-1990s. This continuing economic growth makes a lot of funds available for economic development. These funds, combined with the Small Business Act of 1996, have resulted in a growing interest in entrepreneurship. The Small Business Act of 1996 resulted in the foundation of Ntsika, a government agency that is responsible for implementing support measures for small, micro and medium enterprises that are owned by historically disadvantaged individuals. Ntsika is reorganising at the moment into the Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA) in order to improve the support for small, medium and micro enterprises. Several Banks and NGO's have also recently issued programs in order to support micro entrepreneurs. The question that follows is: are these, often supply driven, services delivered in such a manner that it actually supports micro entrepreneurship?

To assess the support that is provided by institutions, this article will identify barriers that are faced by micro entrepreneurs and key resources that are needed to overcome these barriers. These resources will be related to support dimensions in order to complete a framework that can be used to asses support for micro entrepreneurs. These resources are divided into three key parts: financial, economical and educational resources.

In the remainder of this paper, business literature is linked to literature about market entry barriers combined with the resourced based view and aspects of entrepreneurship literature and development literature into a model that describes the business situation of micro entrepreneurs. The empirical part of this article stresses two cases in which two business start ups are analysed with the help of the new framework.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. §2 provides an overview of literature about micro enterprises and start-ups. The framework that describes the interaction between micro entrepreneurs, entry barriers, resources and support is provided in §3. Two cases show how this framework can be used in practice in §4. The conclusions and recommendations about using the framework for analysing micro enterprise start up are provided in §5.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Entrepreneurship has been an important topic in business literature. Some authors have focussed on the influence of entry barriers on firm start up (Blees et al. 2003:24; Karakaya & Stahl 1989:81). Others have focussed on sole issues like education (Kuratko 2005:580) innovation (Drucker 1998:157) or personal characteristics (Gartner 1985:699) and some attention is given to government support for entrepreneurs (Gnyawali & Fogel 1994:45) but primarily targeted at developed economies.

The literature about micro entrepreneurship is dominated by the support of financial institutions for micro entrepreneurs (Schoombee 2000:752). Entrepreneurship is a growing subject in research in South Africa. Much attention is given to the education of South African micro entrepreneurs (Orford et al. 2004:34; Ladzani & Van Vuuren 2002:157; Mayhofer & Hendriks 2003:597). The importance of policies for supporting micro entrepreneurship is recognised, but the literature focuses on popular South African topics, like entrepreneurial education and micro credits and has not paid much attention to the kind of support that is needed by the micro entrepreneur to overcome entry barriers. Recently, entrepreneurship has been linked to the development of resources (Alvarez & Busenitz 2001:757). Hamel & Prahalad (1993:78) used the concept of stretching resources to explain interactions within a business column. This concept can also be used to study the relation between micro entrepreneurs, resources, market entry barriers and government support. This article will add to the knowledge of micro businesses by integrating these themes into a single practical framework. As a result, the model developed defines what resources are needed by South African micro entrepreneurs to overcome entry barriers. It can therefore be used by consultants, government officials and entrepreneurs.

3 THE FRAMEWORK

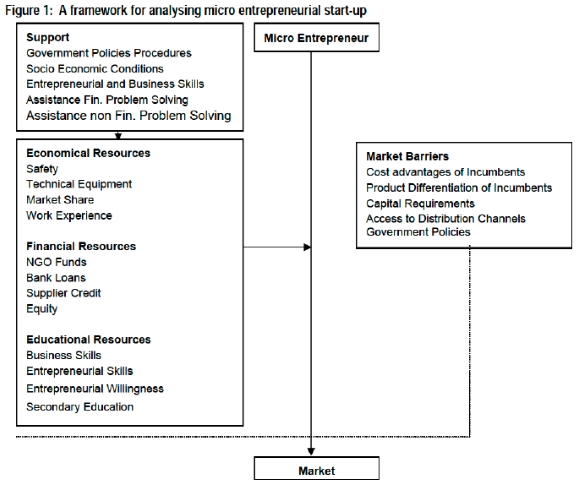

Three considerations entered into the development of this framework. Firstly, a study is made on the needs of micro entrepreneurs in development literature and literature on the subject of micro entrepreneurship. This results in a summation of twelve relevant resources for South African micro entrepreneurial start ups. These resources are divided into economical, educational and financial resources. Secondly, a selection is made out of an extensive list of market entry barriers from literature that applies to micro enterprises. Thirdly, a framework describing the entrepreneurial environment from literature is integrated into the framework with an emphasis on the role of the South African government because of its policies targeted at micro entrepreneurs. This framework contains five dimensions: support, resources, market barriers, market and micro entrepreneurs. The framework is depicted in Figure 1.

The remainder of this paragraph will address these factors more extensively and will elaborate on the considerations which resulted into this framework. However, first micro entrepreneurs have to be understood.

Micro entrepreneurs

According to Gartner (1985:698), an entrepreneur is a person that creates an organisation. Lorsch (1977:3) states that an organization design is management's formal and explicit attempt(s) to indicate to organization members what is expected of them. That means that micro entrepreneurs need at least personnel, partners or agents to direct in a more or less formal way to be considered in this study. The South African government defines a Micro Entrepreneur, for any sector, as a person with less than five employees (Department of Trade and Industry 2004:34). With micro enterprises, the smallest of smallest enterprises are meant, formal and informal.

The current situation of micro entrepreneurs in South Africa is a product of special circumstances. Much attention is given to the phenomenon of 'apartheid' politics that were abandoned in the early 90's under the lead of Nelson Mandela. Many policies are therefore intended to empower Historically Disadvantaged Individuals (HDI's). Because most South African institutions only support this group, this study focuses likewise on micro entrepreneurs that are HDI's.

Entry Barriers

Strategic management literature describes entry barriers from the perspective of the individual firm. Firms have multiple tools to compete with new entrants like patents, diversification and price. Management is forced to think of new strategies to minimise the negative impact of new entrants. These strategies should be original, hard to copy and enduring in order to create a sustainable competitive advantage (Barney 1991:111). In general, six barriers are listed as being most important (Porter 1980:7; Karakaya & Stahl 1989:82). These are cost advantages of incumbents, product differentiation of incumbents, capital requirements, customers switching costs, access to distribution channels and government policy. Some scholars also mention other barriers such as brand name and research & development (Krouse 1984:497; Harrigan 1981:397).

This study will not view barriers from the incumbent firms' perspective but from an entering micro enterprise perspective. Micro entrepreneurs tend to be active in markets without advanced technological processes (Kabecha 1999:118) and capital intense processes (Schoombee 2000:752). Therefore customer switching costs are regarded as irrelevant for micro entrepreneurs because these switching costs are induced by technology (Blees et al. 2003:60).

Resources

According to the resource based view, companies have to own a number of resources to produce certain products or services (Wernerfelt 1984:172). These resources should be valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, competitively superior and unique resources to be of use in competition (Barney 1991:102). These resources are used to make a strategy configuration that is adapted to the environment in such a way that it creates a sustainable competitive advantage. Acquiring unique resources is not a realistic option for micro entrepreneurs. Hamel and Prahalad (1993:78) developed the concept of stretch that does apply to micro enterprises. In order to compete, business owners have to stretch their resources. This can be done in five ways: concentrating resources more effectively on key strategic goals, accumulating resources more efficiently, complementing various types of resources to create higher value, conserving resources when possible and recovering resources from the market place in the shortest possible time.

Barney (1991:101) refers to capital as the combination of resources and capabilities. He uses a classification to describe critical resources and capabilities. Financial capital is access to various kinds of financing, e.g. through the stock market, banks or suppliers. Physical capital is machines, production facilities, geographical locations, access to raw materials and customer markets. Human capital is labour, knowledge, skills and experience. Organisational capital is organisational processes, structures and systems that enable firms to produce the required products and services. Barney's concept of capital includes tangible as well as intangible resources.

The model is restrained to tangible resources. Intangible resources, like competencies, are used to deploy tangible resources in such a manner that companies can compete. These resources are often tacit and hard to measure and are also hard to develop or to provide. Micro entrepreneurs have developed these intangible resources prior to the decision of starting a business and the need for additional tangible resources. Whereas intangible resources are important, they are beyond the scope of this model. Organisational capital is regarded as largely irrelevant when describing resources for micro entrepreneurs. Starting up a business is mainly a creative process and not so much of an organisational process (Greiner 1998:42). The latter phases require more direction and delegation.

Based on research on micro entrepreneurship, four forms of financial resources are distinguished. There is a market failure in the micro enterprise sector because banks are willing to provide financial products but have difficulties of reaching micro entrepreneurs (Schoombee 2000:751). Many micro entrepreneurs are not supplied with loans by the commercial banks but by the Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO's). About five percent of all micro credits throughout the world are issued by NGO's (CGAP 2004:14). In African countries, it is quite common to use supplier credit next to bank credit. These supplier credits are often issued based on ethnicity (Fafchamps 2000:209). Most of these entrepreneurs support their businesses with equity or with support from their family or friends (Kew & Macquet 2002:75).

Four forms of economical resources are distinguished. These are tangible physical resources that are often not possessed by the micro entrepreneurs due to their structural disadvantaged economical position and societal circumstances. In South Africa, entry barriers are high (Kaplinsky & Manning 1998:142) and this is due to a high degree of concentration in many South African markets. This lowers chances for a new company to acquire market share. Next to this, there is a great shortage of technical equipment (Kew & Macquet 2002:82). Businesses in South Africa are in many cases subject to crime. High levels of crime and insecurity constrain private sector investment decisions because they increase the cost of doing business (Ahwireng-Obeng & Desmond 1999:79). Start ups of micro enterprises are often related to prior work experience. However work experience is not commonplace for HDI's because of unemployment.

The literature describes four forms of educational resources. This concept refers to tangible knowledge and skills in the form of, for instance, training, courses, certificates and diploma's. Important educational resources are entrepreneurial skills. These skills are used to implement new plans and new experiences (Ladzani & Van Vuuren 2002:157). Many entrepreneurs, especially survivalists, aren't that interested in entrepreneurial training, however they can benefit from it (Mayrhofer & Hendriks 2003:597). South African entrepreneurs with matric, which is an equivalent to five years of secondary education, have a far better chance of surviving the start-up phase (Orford et al. 2004:18). Ladzani & Van Vuuren (2002:157) add motivation as an essential part of training for entrepreneurs. South Africans have one of the lowest drives to start a business in the world (Orford et al. 2004:50). Ladzani & Van Vuuren (2002:157) mention business skills as a necessary part of education for entrepreneur and it is considered a valuable educational resource because of the administrative burden on small sized businesses (Macculoch, 2001:11). Educational resources can help develop organisational capital in latter stages of the organisational development.

Support to overcome Entry Barriers

In developing countries, like parts of Africa South America and India, many of the micro entrepreneurs start businesses out of necessity. In South Africa, 37% of all enterprises are started out of necessity (Orford et al. 2004:11). These facts demands for a specific view on this group, their problems, barriers and, in case of policies, their specific needs. The goal for policymaking should be to bring entrepreneurs' characteristics as close to fit with opportunities as possible to overcome barriers. In this model, support is used to supply micro entrepreneurs with the necessary resources to overcome barriers. According to Gnyawali & Fogel (1994:46) there are five dimensions in which entrepreneurs can be supported. These are: government policies procedures, socio economic conditions, entrepreneurial and business skills, assistance with financial problem solving and assistance with non financial problem solving. Apart from government policies and procedures, public and private parties can both contribute within these dimensions to the success of micro entrepreneurship. These dimensions can be influenced by supplying micro entrepreneurs with necessary resources as defined above to overcome market entry barriers.

4 CASE STUDIES

The definitions mentioned in the paragraph 'Micro Entrepreneurs' were used to select ten firms from the database of the University of Cape Town in order to do case study research. Two cases, both situated in the Cape Town Area, are selected out of these ten cases. These two cases were selected because they are interestingly contrasting each other for two reasons. Firstly, the personal characteristic of the two entrepreneurs differs much. The first case will elaborate on the enterprise of a middle-aged, low educated male, while the second case describes a young, highly educated female. Secondly, their businesses vary widely. The first case is production oriented and targets a very small segment of companies with a high volume of products, while the second case is service oriented with a wide costumer base and low volumes of services. The two cases illustrate the variety within micro entrepreneurship in South Africa as well as the wider applicability of the framework developed. The cases were constructed with semi-structured interviews at the University of Cape Town (UCT). To assure the consistency of the information, the interviews were supported with company visits and background checks with the Small Business Manager from UCT.

These cases are analysed with the framework displayed above. Firstly, some general information is provided about the entrepreneur, the company and its market. Secondly, the barriers are described that were faced by the entrepreneur during the start up. Thirdly, an analysis is made of the resources that were needed to overcome these barriers. The case description will end with the support that was provided and the outcomes of the support. The first case study will be presented now.

Case 1: Delightful Smoked Products

The Micro Entrepreneur

Delightful Smoked Products produces smoked chicken and distributes it to most of her customers. Delightful Smoked Products delivers to Checkers, Spars, Shoprights, Pick&Pay Hypers and Pick&Pay Family Stores in the Cape Town Area and also supplies a company named Cusitana, a catering company. Cusitana is also active in Johannesburg and Durban. The owner of Delightful Smoked Products is Mr. Teddy Nadioo. Before he started this enterprise, he owned a part-time catering business called delightful caterers together with his wife. Mr. Naidoo thought about starting a business in smoked chicken and enquired information about the production process. A machine that is used to smoke meat costs about R800.000 and that is too expensive. A food technologist from his coloured community told him about the technology of liquid smoking. That was affordable and he decided to enter the market with smoked chicken breasts.

Entry barriers

The market that Delightful Smoked Products entered was not typical for micro entrepreneurs. The market is a product based business to business market and introduced a specific set of barriers for this case. First of all, Delightful Smoked Products did have capital requirements because equipment was needed for smoking chicken. At first, Delightful Smoked Products operated from Mr. Naidoo's private home. Other producers, like Woolworth, had cost advantages, such as experience advantages, that were lacked by Delightful Smoked Products. Smoked chicken in this form was not a new product for the South African market. Access to distribution channels formed a barrier for this product. The first chicken that was smoked by Mr. Naidoo was smoked in his garage. It was impossible to supply customers with that capacity. Furthermore, he needed a van with to deliver his refrigerated goods. Therefore, a capital requirements problem emerged.

Resources

Mr. Naidoo was a starting entrepreneur from a disadvantaged background and he faced a number of barriers. To finance his operation, he took a mortgage on his house and furniture. He was almost sixty years old by then. This wasn't enough to start and he also needed additional financial resources to overcome capital requirements. An enterprise that has the ambition to supply supermarkets demands lot of processes and knowledge. Mr. Naidoo didn't receive the education that would have prepared him for this venture. He also needed production facilities to produce smoked chicken. He also needed to bring his product to the attention of his customers and the market demanded a clear administration about, for instance, hygiene.

Support

Capital requirements were solved with the financial assistance of Khula Enterprises. Khula Enterprises is a government agency that hands out bank guarantees to HDI's. Khula Enterprises guaranteed that eighty percent of the bank loan would be paid back in case of failure, in order to supply mr. Naidoo with the necessary financial resources. A consultant, appointed by Khula, drew up a business plan. Mr. Naidoo wasn't satisfied with the outcome of this plan because the bank didn't offer him working capital, only capital goods. He decided to go to the bank and let them taste the smoked chicken. The bank granted him the loan, including the working capital. Mr. Naidoo, not having finished high school, found it hard to do all the administrative tasks on his own. Experienced family members gave him non-financial assistance with new processes and administration and that improved his costs structure. The success of Delight Smoked Products is related to Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) legislation that requires the larger companies to buy goods from companies that are owned by HDI's. Smoked chicken, even with a unique liquid smoking recipe, could have been supplied by an experienced market player with a better costs structure. Many companies that want to tender for government contracts are required to have previously disadvantaged suppliers. For this reason, Delightful Smoked Products gained access to distribution channels.

Market

This company has been a success story all of its existence. The annual turnover is now an estimated R2.500.000 and growing every year. Delightful Smoked Products started with one employee and counts seventeen full time employees by now. More supermarkets in the Cape Town Area are buying the smoked products and the product line is expanding. In the future Delight Smoked Products will produce hamburgers and chicken burgers from her own recipe. Mr. Naidoo is a devoted Christian and believes that God himself granted him his success and he believes that He will support him in the future. Mr. Naidoo wants to retire on his 65th birthday.

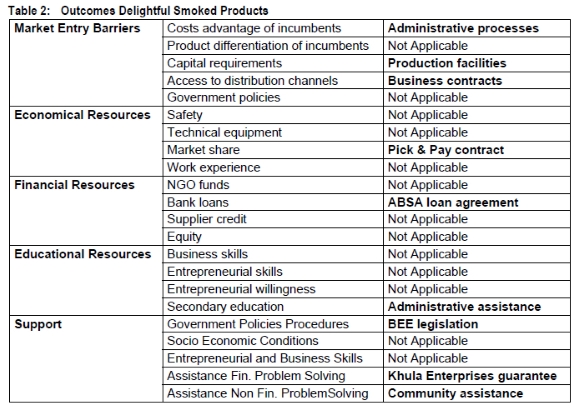

Table 1 below displays the case analysis described above in a scheme. The first and second column lists all factors that were part of the framework (figure 1). The third column shows the specific circumstance of that factor in the case of Delightful Smoked Products. 'Not applicable' means that this barrier, resource or type of support was not part of the process of overcoming the entry barriers in this specific case. Other resources and types of support can be relevant in other cases of micro entrepreneurship.

The first case was an unique form of entrepreneurship in South Africa because of its scale and product orientation. This paragraph continues with the second case; Careervision which is different but just as interesting because of its new business concept and because it provides business to business services.

Case 2 Careervision

The enterprise

Careervision is a recruitment consultant firm. The company is paid by customers per placement. Careervision has a broad variety of customers and clients. These customers are mostly government agencies and NGO's, but may also be commercial clients like Eskom and Circle Capital. Mrs. Faatin Jacobs is the founder of the business. She has a bachelor degree in social science. Initially she worked for a NGO named Top Jobs which was funded by the Dutch CWI (Centre for Work and Income). The South African Labour Department was not really supporting the initiatives of Top Jobs and the CWI stopped funding the NGO. Mrs. Jacobs was allowed to use the database, together with a colleague, for commercial purposes.

Entry Barriers

The database from Top Jobs was already in place. Careervision just took over most of the procedures and knowledge that was left behind. However, to start was not easy because Top Jobs used to deliver services for free and Careervision needed to make profit. Mrs. Jacobs and her partner were inexperienced in doing business. The CWI gave Mrs. Jacobs two months of salary and an additional R10000. Careervision had capital requirements because Mrs. Jacobs needed an office and facilities. She also faced a barrier in the form of cost disadvantages. Mrs. Jacobs had only been active as supporting staff and entrepreneurship was more difficult than she had expected. She filled much of her time with administrative tasks.

Resources

Mrs. Jacobs was supportive staff in her former role and this was changed into a leading role. From an educational resource perspective, she needed entrepreneurial and business skills to be successful in business. Mrs. Jacobs did not need, or ask for, additional financial resources. She had the money she needed; she was only looking for a place to work from and equipment to work with. These were primarily technical resources like an office and office equipment.

Support

Careervision had capital requirements and needed a business premise to receive clients and customers. A businessman from Mrs. Jacobs Islamic community offered a spare office in his building as a form of non-financial assistance. Her mother helped him with his administration for a few hours per week in exchange.

An external accountant helped Mrs. Jacobs with business administration. He agreed to help her out for a small fee. She was registered and became a suitable partner for government agencies and NGO's. Next to this, she became a member of the Cape Chamber and the South African Business Women Council. Via these organisations she attended courses and she gained the required entrepreneurial and business skills to manage her company.

Market

The annual turnover of Careervision is an estimated R150.000 at the moment. Careervision employs two staff members. Careervision stays independent but larger companies, for instance Deloitte, are interested in a take-over. The change from free service to commercial service forced Careervision into a slow start, but Mrs. Jacobs coloured community and family gave her the necessary support to survive this period. The company is more professional now and, according to Mrs. Jacobs, the future is bright.

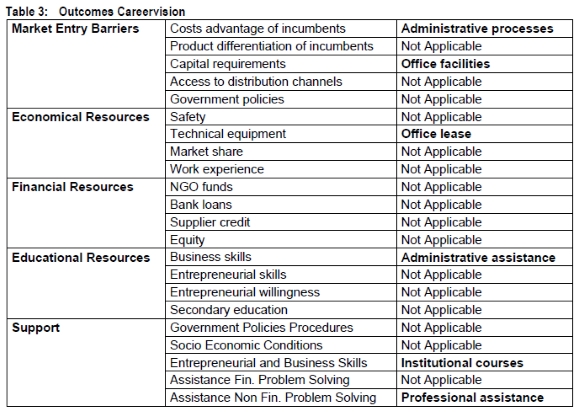

Table 2 displays the outcomes of this case study in a scheme. Also in this case, the first and second columns mention all factors that were part of the framework (figure 1). The third column will mention the specific circumstance of that factor in the case of Careervision. Also in this overview, 'Not applicable' means that this barrier, resource or type of support was not part of the process of overcoming the entry barriers.

The next paragraph provides conclusions and recommendations for the article as a whole.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This article focussed on South African micro enterprises in the start-up phase. Two case studies were used to illustrate a model for analysing the provision of basic resources to overcome market entry barriers. In order to analyse the situation of South African micro entrepreneurs, the literature about market entry barriers was combined with the resourced based view, with aspects of entrepreneurship literature and development literature added. This has resulted in a new comprehensive framework for analysing entry barriers which will enable government agencies, consultants and micro entrepreneurs to make a faster and more accurate evaluation of business plans and support.

Most scholars identify resources that are valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, competitively superior and unique to be of use in competition. The framework that is developed in this article uses the idea that entrepreneurs can stretch certain resources in order to acquire an unique position in the marketplace. It has therefore more fit with the reality of micro entrepreneurs. In the case of Careervision, Faatin Jacobs managed to conserve the clientele list from a disbanded NGO which gave her a head start in the market place for job agencies.

The framework identifies twelve types of resources that can be identified as relevant for micro entrepreneurs. These resources are divided into financial, economical and educational resources. These resources tend to be tangible and not unique like, in the case of Delightful Smoked Products, an oven that can be used for smoking chicken or a van that can be used for transporting refrigerated goods.

The market entry barriers for micro entrepreneurs differ from these large and medium sized enterprises, because the markets for micro entrepreneurs are usually not dominated by expensive and advanced technological processes. Entering markets is, from the micro entrepreneurs perspective, especially about overcoming barriers like 'experience disadvantages' with business administration and also 'capital requirements' due to poverty.

The cases Delightful Smoked Products and Careervison also illustrate the support structures that are prevalent in South Africa. The demand for support is very clear in both cases. Entry barriers such as capital requirements and access to distribution channels are in both cases solved by resources that were supplied by government agencies and NGO's. The two cases articulate the applicability of the model as well as the need for support in the start up phase of micro enterprises.

In order to give support to micro entrepreneurs, institutions should supply basic resources. On the other hand, just handing over money to micro entrepreneurs has little use. The idea behind this model is that micro entrepreneurs need to have a business idea to be considered for support. If micro entrepreneurs meet this condition, institutions can bring micro entrepreneurs close to fit with the targeted markets by supplying them with resources.

This new model has implications for micro entrepreneurs, consultants, institutions and science alike. Micro entrepreneurs should become, or made, aware of the kind of support they need. They should ask themselves what kind of market they are entering and what kind of entry barriers they are facing. To solve these barriers, they can try to obtain resources from a supporting institution. This awareness can be enhanced by advice from small business consultants or liaison agents. Note however, that the framework does not recommend consultants to draw up full business plans but that it suggests that consultants link business ideas with barriers, resources and support.

The supporting institutions should make strategies accordingly and design an operational structure that supplies all the necessary resources in a certain region of urban area. Consultants who are accredited by government agencies should therefore become experts on government support and resources.

The final recommendations based on this framework are of a scientific nature. Additional surveys on the demand of resources could give policymakers more insight in specific needs in South Africa's various regions. The framework developed could also be applied in different settings and countries like other developing regions or perhaps even small businesses owned by minorities in first world countries. Most of all, South African policymakers, scientists and consultants should examine if institutions, like the newly founded organisation of SEDA, are in fact supporting with resources that will lead to successful cases of micro entrepreneurship in the near future.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AHWIRENG-OBENG F & DESMOND P. 1999. Institutional obstacles to South African entrepreneurship. South African Journal ofBusiness Management, 30(3):78-87. [ Links ]

ALVAREZ SA & BUSENITZ LW. 2001. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of Management, 27(6):755-775. [ Links ]

BARNEY JM. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1):99-120. [ Links ]

BLEES J, KEMP R, MAAS J & MOSSELMAN M. 2003. Barriers to entry: differences in barriers to entry for SMEs and large enterprises. Zoetermeer: EIM. [ Links ]

CONSULTATIVE GROUP TO ASSIST THE POOR. 2004. Annual report. Washington: CGAP. [ Links ]

DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY. 2004. Annual review of small business in South Africa. Johannesburg: Department of Trade and Industry. [ Links ]

DRUCKER PF.1998. The discipline of innovation. Harvard Business Review. 76(6):149-157 [ Links ]

FAFCHAMPS M. 2000. Ethnicity and credit in African manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics, 61(1):205-236. [ Links ]

GARTNER WB. 1985. A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of Management Review, 10(4):696-706. [ Links ]

GNYAWALY DR & FOGEL DS. 1994. Environments for entrepreneurship development: key dimensions and research implications. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(4):43-62. [ Links ]

GREINER LE. 1998. Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, 76(3):55-68. [ Links ]

HAMEL G & PRAHALAD CK. 1993. Strategy as stretch and leverage. Harvard Business Review, 71(2):75-84. [ Links ]

HARRIGAN KR. 1981. Barriers to entry and competitive strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 2(4):395-412. [ Links ]

KABECHA WW. 1999. Technological capability of the micro-enterprises in Kenya's informal sector. Technovation, 19(2):117-126. [ Links ]

KAPLINSKY R & MANNING C. 1998. Concentration, competition policy and the role of small and medium sized enterprises in South Africa. Journal of Development Studies, 35(1):139-161. [ Links ]

KARAKAYA F & STAHL MJ. 1989. Barriers to entry and market entry decisions in consumer and industrial goods markets. Journal of Marketing, 53(2):80-91. [ Links ]

KEW J & MACQUET J. 2002. Profiling South Africa's township entrepreneurs in order to offer targeted business support. Cape Town: Graduate School of Business. [ Links ]

KROUSE CG. 2001. Brand name as a barrier to entry: the realemon case. Southern Economic Journal, 51(2):495-502. [ Links ]

KURATKO DF. 2005. The emergence of entrepreneurship education: development, trends and challenges. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 29(5):577-597. [ Links ]

LADZANI ML & VAN VUUREN JL. 2002. Entrepreneurship training for emerging SMEs in South Africa. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(2):154-161. [ Links ]

LORSCH JW. 1977. Organizational design, a situational perspective. Organizational Dynamics, 6(2):2-14. [ Links ]

MACCULOCH F. 2001. Government administrative burdens on SMEs in east Africa: reviewing issues and actions. Economic Affairs, 21 (2):10-16. [ Links ]

MAYHOFER AM. & HENDRIKS SL. 2003. Service provision for street-based traders in Pietermaritzburg, Kwazulu-Natal: comparing local findings to lessons drawn from Africa and Asia. Development Southern Africa, 20(5):595-604. [ Links ]

NAFUKHO FM. 1998. Entrepreneurial skills development programs for unemployed youth in Africa; a second look. Journal of Small Business Management, 36(1):100-103. [ Links ]

ORFORD J, HERRINGTON M & WOOD E. 2004. GEM: 2004 South African executive report. Cape Town: Graduate School of Business. [ Links ]

PORTER ME. 1980. Competitive Strategy. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

PORTER ME. 1990. The competitive advantage of nations. New York: The Free Press. [ Links ]

SCHOOMBEE A. 2000. Getting South African banks serve micro-entrepreneurs: analysis of policy options. Development Southern Africa, 17(5):751 -767. [ Links ]

WERNERFELT B. 1984. A resourced-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2):171 -180. [ Links ]