Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.3 no.1 Meyerton 2006

RESEARCH ARTICLES

A study of work attitudes in an African country

D M Akinnusi

Graduate School of Business, Northwest University

ABSTRACT

The work attitudes of 537 Swazi employees from more than 60 organizations are examined. Work is seen by more than 50% of the respondents as important for its intrinsic, physical, social and financial values. Working hard is also seen as instrumental to promoting future career, happy home and social life, although it appears to have less role in providing for a comfortable living and retirement needs. Aspects of the job which are liked or disliked are similar to the motivation-hygiene factors of Herzberg et al. (1959). Furthermore, there is evidence of unhappiness with their present jobs and their organizations. Moreover, these negative attitudes have begun to affect the respondents' attitudes towards life in general. Suggestions for improving job attitudes are made.

Key phrases: Work stimuli, job experiences, attitudes, impact on other aspects of life

INTRODUCTION

Work attitudes mean the workers' disposition to the content and context of their work. Work attitudes have been intensively studied because of their relationship to employee behaviour and performance. It has been shown that positive attitudes are associated with high job satisfaction, involvement, loyalty and effort-on-the-job (Mirvis & Kanter 1996) while a negative relationship has been established between work attitudes and absenteeism, turnover, tardiness, accidents, grievances and strikes (Akinnusi 1996a; Vroom 1964; Zimbardo Ebbesen & Maslachi 1990, 1996). Negative work attitudes as well as the efforts to change them are, therefore, costly to the organization (Cascio 1991). This study is aimed at measuring Swazi employees' attitudes to their work in the hope of providing answers to workers' frustration, especially as the country is experiencing waves of industrial unrest.

THE COUNTRY

The 1998 Census put the population of Swaziland at about one and half million. It is, therefore, one of the smallest countries in Africa, albeit with a very strong traditional culture. With a rather homogenous population, deriving from the Nguni stock of Bantus, Swaziland emerged, in 1968, from colonial rule largely characterized by land expropriation and labour exploitation (Booth 1982; Daniel 1982 & Fransman 1982). During the apartheid regime, Swaziland was a haven for South African companies evading international sanction. Other companies mostly from Asian countries also featured prominently in the economy. Today, Swaziland has both a dual economy and a dual government, headed by a traditional monarchy, which makes the country unique among other modern African nations.

In the sections that follow, the theoretical framework for understanding the determinants of attitudes to work is presented, followed by a review of relevant literature. The details of the empirical study undertaken are then reported. The findings of the study are discussed and suggestions for further studies are indicated.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND LITERATURE REVIEW

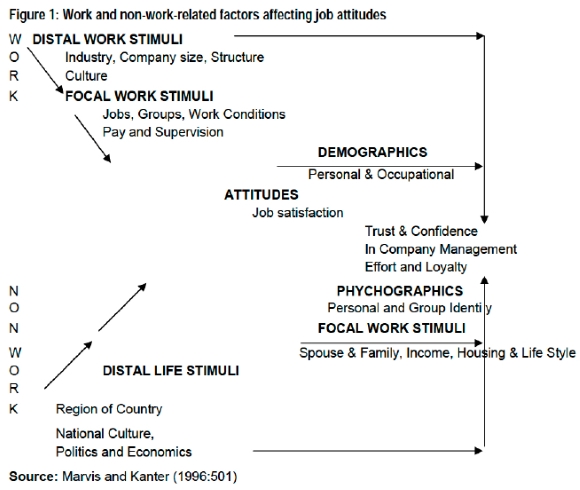

The theoretical framework postulated by Mirvis and Kanter (1996) shows that attitudes to work are influenced by work and non-work-related factors (see Figure 1).

Work-related factors

The three sets of work-related factors are distal work stimuli, focal work stimuli and demographics. Distal work stimuli consist of factors such as company size, shape, industry and technology which define the formal organization and determine the mix of jobs, patterns of employment and promotion and levels of compensation within firms. Together with company culture, these elements represent contextual factors for employees.

The focal work stimuli, on the other hand, are the characteristics of jobs, work groups and supervision as well as working conditions, performance appraisals, pay practices, etc., which represent the contents of employment and are the "best" predictors of employees' attitudes and the most likely subjects of their praise or criticism.

Finally, work attitudes are also influenced by the demographic make-up of an organization. Mirvis and Kanter (1996) believe that demographics have a bearing on people's opportunities and experiences at work in the sense that people at different levels in the organization have different types of jobs, gain distinct rewards and, in general, have different attitudes towards their jobs. Also, studies have found differences in expectations and values across income strata, gender, race, etc. (Yankelovich 1979).

Non-work-related factors

Attitudes are also influenced by non-work-related factors, such as psychographics, focal life stimuli and distal life stimuli. A broad range of studies concerned with "values and life styles" confirm that people's psychological predisposition and outlooks have a bearing on their attitudes and behaviour as consumers and employees. For example, people's self-esteem, locus of control, attitudes toward authority, trust in other people, etc., impinge on attitudes about the job and one's organization (Lawler 1973).

Psychographic characteristics are, in turn, influenced by stimuli in the environment. The non-work equivalent of the content of a job is the content of people's lives - their family structure, income, housing, and life style. These factors, too, have a bearing on people's life transactions, including those involving their work, their organization, their co-workers and their working conditions. These factors serve to modify the perceived content of their work and its relative desirability.

Finally, the general state of the economy, developments in politics and society are other factors affecting people's attitudes. These contextual forces, too, affect how companies do business which, in turn, generally shape employees' opinion of their employers and jobs. The region of the country, nationality and differences in national culture also play a role in shaping life attitudes and those having to do with the workplace (Hofstede 1980).

This study is more concerned with the impact of work-related stimuli on job attitudes and hence the review will concentrate on those issues.

Generally speaking, studies of job attitudes of Swaziland workers are scarce. The few, however, attest to a very serious problem in this regard from the earliest times. McFadden (1982:146) was one of the earliest writers to call attention to the plight of women in the wage labour in Swaziland. She said that women formed a "reserve army of labour, to be drawn into production when the need arises and thrown out when the need no longer exists". Women were preferred in agriculture because they were more careful, patient and manually dexterous, yet poorly paid and had no job security. They lived in slums constructed by them near the plantations and their working conditions in the fields and in the factories leave much to be desired. The same conditions were reported by Armstrong (1985) in another investigation into the working lives of women in wage employment. Sikhondze (1993) attributed the industrial unrest in the sixties and seventies to poor wages, discriminatory practices, un-safe busing and insanitary conditions in the mining and agricultural companies in the country. The state of occupational health and safety have not improved much even with legislation, and many deaths are due to occupational harzards (Akinnusi 1996b). The study by Yoder and Eby (1990) on quality of working life in some of Swaziland's ministries indicated low levels of participation in decision-making as well as low levels of job satisfaction by a substantial proportion of the respondent employees.

THE PRESENT STUDY

This study aims at providing answers to the following questions:

1 What motivates Swazis to work?

2 What role does work play in the lives of Swazi workers?

3 What are the current job experiences of Swazi workers?

4 What is the Swazi workers' outlook toward life?

5 What are the implications of all of these for improving quality of working life?

Methodology

Instrument

The study reported here is part of a larger study into the quality of working lives of Swazis. A questionnaire was constructed to obtain biographical data (such as gender, age, educational and salary levels) and organizational data (such as size and ownership. A series of questions probed why Swazis work and the value of work in their lives. Perceived job satisfaction, involvement and commitment were also measured.

Procedure

The questionnaires were administered by trained research assistants and subjects came from employees in the countries two largest cities - Mbabane and Manizini -where most more than 90% of the industrial activities and government ministries and parastatals are located. All together, 537 usable questionnaires were received. The respondents came from 63 organizations, comprising financial (6), manufacturing and processing (43), government (8) and parastatal (6) organizations. It was felt that the sample was representative of the employment situation in Swaziland. Of 537 respondents, 131 or 26.2% are employees from financial institutions; 225 or 41.9% from manufacturing and processing establishments; 136 or 25.4 from government ministries and 37 or 6.5% from parastatals.

Sample Characteristics

Of the 537 respondents, there were 310 males (57.7%) and 210 females (39.1%); others (17 or 3.2) did not identify their sex. Majority (77%) of the respondents is below 35 years of age; and over 60% have an overall total work experience of more than five years. About half of the respondents have spent up to five years in the particular organization where they were surveyed. High school and diploma students form the bulk (nearly 70%) of the respondents and degree holders formed only about 14%. About 42% earn E10, 000 per annum or less, 34% earn between E10, 000 to E20, 000 per annum and only 19.2% earn over E20, 000 per annum. Thus, the sample is mostly representative of low and middle level employees.

RESULTS

Reasons for working

Why Swazi workers like to work and the instrumental values of work were examined through a series of questions. Questions one is: "If you were to get enough money to live as comfortably as you would like for the rest of your life, would you continue to do any work?" The responses showed that 434 or 80.8% said "yes" while 71 or 13.2% said "no" with 32 or 6% not responding. The results showed that an overwhelming majority would like to continue working even if they had the means to support themselves for the rest of their lives. This is a clear indication that work has become an integral part of the life of the majority of the respondents.

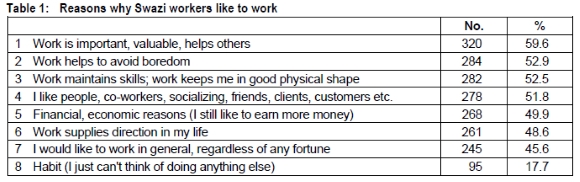

The next set of questions attempted to probe into the reasons why respondents would continue to work if they were able to live as comfortably as they would like for the rest of their lives. Table 1 shows the reasons given.

It will be seen from the table that most people like work for a variety of reasons, which are both intrinsic and extrinsic. The most significant variable was the value of work as a means of helping others. Work as a means of avoiding boredom is second. This is followed by the physical, economic and social contributions of work to people.

Those who would not like to do any work if they had enough money to live as comfortably as they would like for the rest of their lives cite other interests as more important to them. These interests include going into business, marriage, further education, and travelling or just enjoying the company of their families. Only about 20 or 3.7% said that they generally hated work and about 32 or 6% said they were getting too old and ready to retire.

Aspects of the job that are liked or disliked

Frequently cited aspects of the job which the respondents liked are mostly motivators (Herzberg et al. 1959) and these include promotion, chances for training, the challenge in the job as well as opportunities to interact with others. This paints a different picture from the stereotypical view of African workers as mostly motivated to work by extrinsic factors.

Aspects of their present work disliked by most people are too many rules, exploitation, ill-treatment, racism, lack of accommodation, poor salary and poor working conditions. These fall mostly into the category of Herzberg's (1959) dissatisfiers. The role which work plays in the lives of the respondents is considered next.

The Value of Work

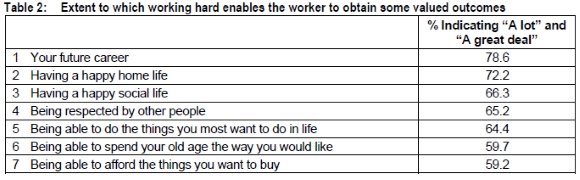

In evaluating the role of work in the lives of the respondents, they were asked to rate the extent to which certain outcomes depend on how well workers perform in their present jobs. The outcomes were rated on a five-point scale ranging from "A lot" (5) to "Not at all" (1). Only the responses of those who checked "A lot" and "A great deal" on each item are shown on Table 2.

Performing well in the respondents' present jobs is instrumental to advancing their future careers and maintaining a happy home life. To some extent, it is also instrumental in having a happy social life. It is least instrumental in being able to afford the things the respondents want to buy or the way they would like to spend their old age. These latter issues reflect inadequacies in the salary, wages and retirement benefits enjoyed by the workers, a recurrent feature of Swazi labour market.

Job Experiences and Attitudes Towards Organizations

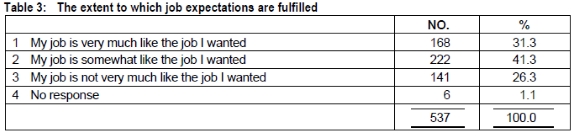

A series of questions probed the job experiences, expectations and attitudes towards their organizations. Question 1 is the extent to which the respondents' present jobs measured up to what they had expected when they first took up their jobs. The responses are given in Table 3.

Thus, about 68% of the respondent employees said that their present jobs are either "somewhat" or "not very much" what they wanted. Only 31.3% felt it was "very much" like what they anticipated. This means that majority of the workers are not happy with their present jobs.

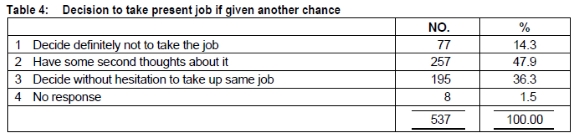

The next question was "Knowing what you now know, if you had to decide all over again whether to take the job you now have, what would you decide"? The results are presented in Table 4.

Again, it will be seen that more the 60% of the respondents would either decide definitely not to take up the same jobs or have some second thoughts about doing so. About 36% would decide without hesitation to take up the same job. This confirms the conclusion that the majority of the respondents are not satisfied about their jobs. This is confirmed in their response to the next question: "All in all, how satisfied are you with your job?": 238 or 44.4% were either not satisfied or not at all satisfied whereas 291 or 54.2% admitted that they were either satisfied or very satisfied with their jobs. Eight or 1.5% did not respond. Thus, only slightly more than half of the respondents in this study have positive attitudes towards their jobs, while nearly 45% exhibited negative attitudes.

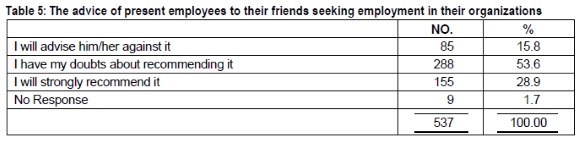

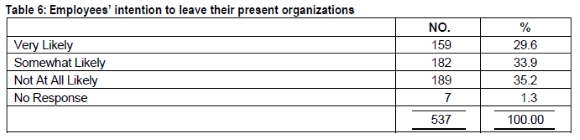

Two questions were asked to assess the degree to which the respondents like their organizations. The first one was: "If a good friend of yours told you he/she was interested in working for your employer, what would you tell him/her?" The second is the likelihood that employees would make a genuine effort to find a new job. The responses to these questions are shown in Tables 5 and 6.

From Table 5, it is clear that only about 29% would strongly recommend their organizations to their friends looking for jobs whereas about 70% would either advise them against it or would have second thoughts about recommending it. In other words, the majority of the respondent employees would not eagerly recommend their organizations to their friends. The intention to leave, as shown in Table 6, also indicates that the majority of workers in the sample (63%) would be making some efforts to leave their present employers in the near future. Only 35% of them would not make any efforts to leave. However, in a very loose labour market economy as Swaziland is experiencing, where the spectre of retrenchments looms large over workers in most sectors of the economy, and also where very few jobs are being created, the desire to leave present employment may be just mere wishful thinking. Hence, organizations are likely to harbour disgruntled employees who are eager to leave but have no alternative sources of employment.

The Impact of Work on Other Aspects of Life

Work occupies a central place in the lives of employees and feelings about their jobs invariably affect many aspects of their lives. In the same manner, an employees' state of mind about life in general, its moral, political and world problems, the state of one's health or marriage and the behaviour of his/her children can affect employees' reactions to their jobs. Hence, Biesheuvel (1984:26) noted that "Life and work are thus totally intertwined and mutually interactive".

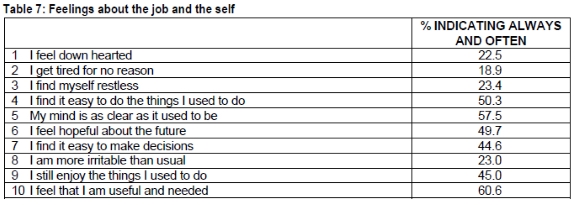

This study, therefore, wanted to know how the respondents' feelings about their jobs affect their perception of themselves and their lives. Table 7 presents the results.

While about 29% of the respondents never felt down-hearted when they think about themselves and their jobs, 48.1% sometimes felt so and about 23% often and always felt so. Similarly patterns emerged with reference to being tired and restless. Nearly 23% expressed being often or always more irritable than usual while 41% sometimes felt so and only about 36% had never felt so. These are indications of physical exhaustion, behavioural as well as psychological stress.

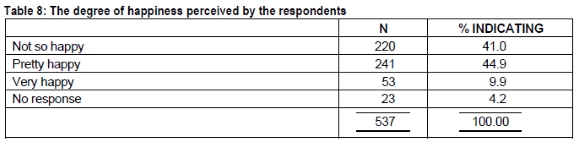

The final question was: "Taking all things together, how would you say things are these days for you? Would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy or not so happy these days?" The responses are given below in Table 8.

About 41% were not so happy with the way things are these days, while nearly 45% are pretty happy and only about 10% are very happy. This shows that a substantial percentage of the respondent workers (41%) are not happy with the way things are these days.

DISCUSSION, IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The results of this study showed that an overwhelming majority of the sample (80.8%) would continue to work even if they have enough money to live comfortably for the rest of their lives. The significance of this is that work is greatly valued by the workers for various positive reasons such as being able to help others, being able to keep oneself busy and in shape and for providing opportunities for socializing. Work is also seen as providing direction in one's life. Motivating workers can therefore lead to positive attitudes to their work. Only 20 or 3.7% of the sample subscribed to pure idleness.

There is, however, evidence of poor morale and low commitment to organizations among the respondents. Frequently mentioned causes of poor morale are bureaucratic controls, ill-treatment, racism, exploitation, poor salaries, lack of accommodation and poor physical working conditions. Hence, about 68% of the respondents felt that their present jobs were not meeting their expectations. Also, 62% would not like to take up their present jobs or would have second thoughts about it. All things considered, 44% were dissatisfied with their jobs and 69% would not like to recommend their present organizations to others, while similar proportion would be making genuine efforts to find jobs with new employers. These findings are similar to those of Blunt (1983) and Machungwa and Smith (1983) in their studies of workers in Kenya and Zambia respectively.

Frustration in meeting basic needs has also led to a feeling of alienation, distress and helplessness which some of the workers have developed in their outlook towards work and life. Work is not seen as being instrumental in helping the worker to afford the good things of life or in providing for a comfortable retirement. This situation must have contributed to the waves of industrial unrest which have gripped the nation as from 1992 onwards (Akinnusi 1996a).

Improvements are, therefore, required in the quality of working life of Swazi employees. At work, efforts must be made to humanize the work place by meeting the basic needs of the worker in terms of good salaries and fringe benefits, designing intrinsically motivating jobs as well as providing hygienic working conditions. The social relations at work, especially supervisor-subordinate relationships, need improvement in order to give the worker a sense of dignity and to create a psychologically safe environment in which workers can exercise initiative and drive. This, therefore, requires that bureaucratic structures and controls be relaxed and an open, democratic styles of leadership be adopted. Thus motivated and empowered, Swazi employees would develop positive attitudes to their work, leading to greater worker-management co-operation rather than confrontation, as is now the case.

LIMITATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER STUDIES

This study has not concerned itself with the impact of non work-related issues on job attitudes, but they are, nonetheless, potent forces. Future studies should look into the impact of national cultures, political and economic factors as they affect workers' attitudes to their jobs. Available evidence suggests that Swaziland had begun to witness a deteriorating quality of life as from the seventies when its population began to explode, resulting in a decreasing rate of basic needs satisfaction (housing, education, health and transportation, etc.) among the populace (Matsebula1984; Mlongo 1992; Sentongo 1991). Furthermore, Swaziland has been exposed intermittently to spells of severe droughts, thus aggravating the economic and social lives of the people and further impoverishing the working class. The impact of these non work-related issues on job attitudes deserve further investigation.

CONCLUSION

While employers must provide better incentives and psychologically safe environment for workers in order to improve their work attitudes, simultaneously, government must also address the basic needs of the citizenry such as portable water and bore holes, good roads, electricity, affordable and accessible health and educational facilities. Also, government has to play a more innovative role in mediating the relationship between workers and management than hitherto, so that the power of unions in improving the economic and social conditions of work is enhanced. The recent waves of industrial unrest and mass stay-away experienced in the kingdom underscore the urgent need for greater cooperation among the social partners, so that the much-needed climate of industrial peace reigns in the kingdom.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AKINNUSI DM. 1996a. "Industrial Relations and the Development of Swaziland" South African Journal of Labour Relations, Volume 20, Number 4, 22-35. [ Links ]

AKINNUSI DM. 1996b. "Occupational Health and Safety in Swaziland" Africa Insight, Volume 26, Number 2, 130-139 [ Links ]

ARMSTRONG ALICE. 1985. A Sample Survey of Women in Employment in Swaziland. SSRU, University of Swaziland. [ Links ]

BIESHEUVEL S. 1984. Work Motivation and Compensation: Volume 1, Motivational Aspects. Johannesburg: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

BLUNT PETER. 1983. Organizational Theory and Behaviour: African Perspective. London: Longmans. [ Links ]

BOOTH ALAN. 1982. "The Development of Swazi Labour Market, 1900-1968", South African Labour Bulletin: Focus on Swaziland, Volume 7, No. 6, pp 34-57. [ Links ]

BRIDGES WILLIAM. 1994. "The End of the Job", Fortune, September, pp. 46-51. [ Links ]

CASCIO WF. 1990. Costing Human Resources: The Financial Impact of Behaviour in Organizations, (Third Edition), PWS Kent Publishing Company. [ Links ]

HERZBERG F, MAUSNER B AND SYNDERMAN B. 1959. Motivation to Work. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

HOFSTEDE G. 1980. Culture and Its Consequencies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

KIGGUNDU MN. 1989. Managing Organizations in Developing Countries. Kumarian Press Inc. [ Links ]

LAWLER EE. 1973. Motivation in Work Organizations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

MACHUNGWA PD AND SCHMITT N. 1983. "Work Motivation in a Developing Country", Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(1), pp. 1-42. [ Links ]

MATSEBULA MS. 1984. "Human Resources Development in Swaziland: Role of Domestic and Foreign Sources in the Context of A Basic Needs Approach" Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the Swaziland Institute of Personnel and Training Management; Ezulwini, Oct. 26. [ Links ]

MCFADDEN PATRICIA. 1982. "Women in Wage Labour in Swaziland: A Focus on Agriculture", South African Labour BUIIetin: Focus on Swaziland, Volume 7, No. 6, pp. 140-166. [ Links ]

MHLONGO T. 1992. "Extent to which Modern Health Services are accessible and affordable in Swaziland. In Okore A. (Ed) Proceedings of the National Workshop on Population and Development: Focus on Swaziland, UNFPA/UNDESD-Supported Training Programme in Demography, University of Swaziland, Mountain Inn, 9-11 October, 136-145. [ Links ]

MIRVIS PH AND KANTER DL. 1996. "Beyond Demography: A Psychographic Profile of the Workforce" In Ferris, G.R. and Buckley, M.R. (Eds.) Human Resources Management: Perspectives, Context, Functions and Outcomes. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 499-515. [ Links ]

SENTONGO C. 1991. "School Mapping and Micro-planning in Swaziland" In Adepoju, A. (Ed) Swaziland: Population, Economy and Society. New York: United Nations Population Fund, 69-95. [ Links ]

SIKHONDZE BONGINKOSI. 1993. "The Causes of Poor Industrial Relations in Swaziland: A Historical Analysis, 1948- 1963", Paper presented at the Economic Society of Swaziland Forum. [ Links ]

VROOM VH. 1964. Work and Motivation. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

YANKELOVICH D. 1979. "Work, values and the new breed" In C. Keer and J,M, Rosow (Eds.), Work in America: The decade ahead. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. [ Links ]

YODER RA. AND EBY SL. 1990. "Participation, Satisfaction and Decentralization: The Case of Swaziland". Public Administration and Development, Volume 10, 153-163. [ Links ]

ZIMBARDO PG, EBBESEN EB AND MASLACHI C. 1990. Influencing Attitudes and Shaping Behaviour (Third Edition) New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]