Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.3 no.1 Meyerton 2006

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Information Technology: management issues in the execution and termination phases of outsourcing contracts

D CoetzeeI; N LessingII

ISiemens Ltd

IIUniversity of Johannesburg

ABSTRACT

This article concerns the investigation of management issues in the execution and termination phases within information technology outsourcing (ITO) contracts. The ITO life cycle is used as the flow structure for the investigation. The user expectations that occur in the execution and termination phases of the ITO life cycle are identified. The "Coetzee solution framework" is used to ensure that the identified management problems are addressed in a structured approach. The execution and termination phases of the ITO life cycle, with its expectations and problems, are discussed in the context of the solution framework.

Key phrases: information technology, information technology outsourcing, execution phase, termination phase, management issues

BACKGROUND TO THE MANAGEMENT ISSUES IN THE EXECUTION AND TERMINATION PHASES

This is the fourth article in the series of articles around the management issues that arise in information technology outsourcing (ITO) contracts. The first three articles focused around the initiation phase, the due diligence and contracting phase and the transition phase. It was clearly positioned that the first three phases set the foundation and user expectations on which the future success of an ITO is based. Since organisations now view ITO as a vehicle to increase competitiveness in combination with the traditional drivers of IT outsourcing namely to reduce operation costs, improve information systems (IS) flexibility, focus on core competencies, and increase operational efficiency, it is critical that the foundation phases (initiation, due diligence and contracting, transition) are properly executed (Casale 2001:3).

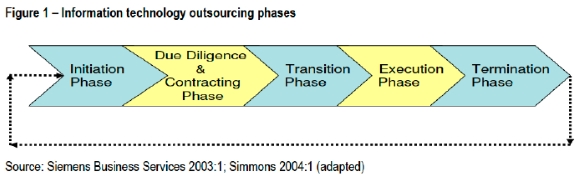

There are essentially five main phases in an information technology (IT) outsource contract life cycle as is depicted in Figure 1. Each of these phases will be briefly described in order to give context to the ITO life cycle phases. This article will only focus on the execution and termination phases of ITOs to describe the management issues, user perception problems and the relevant solutions that are available to address the management and user perception issues.

• Initiation phase - This is where the organisation has decided that they need to streamline the IT environment and as such start looking at the components they wish to outsource, co-source or run internally. The organisation will also at this stage typically prepare a request for information (RFI) to see what the vendors in the market can offer.

• Due diligence and contracting phase - Once the organisation has identified the vendor or vendors that they wish to continue working with, they open up their environment to the vendor to investigate the environment thoroughly in order to come up with the best and final offer (BAFO). There after the organisation evaluates the BAFOs and decides on the final vendor. Contract negotiation is entered into to finalise the outsourcing agreement.

• Transition phase - Most of the vendors then enter into a transition phase whereby the services, possibly the staff, assets, and management is handed over to the vendor.

• Execution / operations phase - Once the transition is complete the vendor assumes the responsibility for the operations of the contracted services for the organisation. This carries on for the full term of the contract period.

• Termination phase - When the contract period reaches its end, the contract is either renewed or terminated. In the event of termination, the services are either transitioned back to the organisation or to another vendor depending on the organisation's experience regarding outsourcing.

Each of the above-mentioned phases has a set of problems that arise and seem common to all outsource contracts. While many of the problems are brushed away initially, they often have significant influence in the longer term relationship and ability to deliver service between the vendor and the organisation.

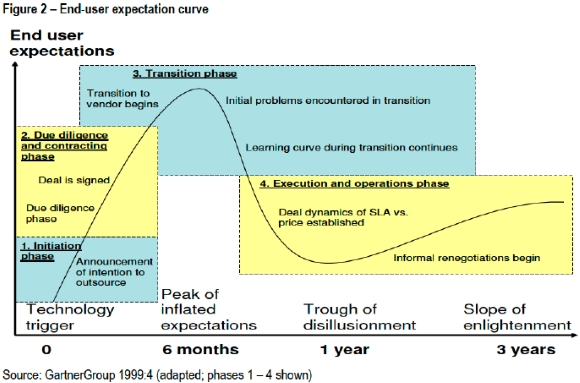

The problems associated with the ITO lifecycle can be linked to the Gartner expectation curve on ITO (GartnerGroup 1999:4). The expectation curve is based on the expectations that are set by the vendor at the beginning of the ITO, but also by the end users within the customer who believe that dramatic improvements in service levels can be expected in very short times. Figure 2 illustrates the user expectation curve with the first four phases of an ITO mapped to the various stages in user expectation.

In this article the execution and termination phases are discussed in the context of the problems that typically arise as time progresses. This is not meant to be an exhaustive discussion on the issues, but merely a short overview of some of the main problems that do occur.

PROBLEMS THAT ARISE WITHIN THE EXECUTION AND TERMINATION PHASES

Execution phase

Entering the operations or executions phase is extremely difficult as the user expectations are dropping radically and the organisation essentially enters a trough of disillusionment; refer to Figure 2 (execution and operations phase). At this stage everything in regard to the ITO starts being reviewed. The main issues normally arise around price and the related service levels. Since many organisations have not planned the initiation well and not done their homework regarding their expectation on the environment, in terms of costs and what the actual service levels are that they were experiencing prior to the ITO, they assume they are being overcharged and are not receiving an equivalent service level. Research (GartnerGroup 1999:10) has shown that while many organisations make a huge one-time effort at the time of outsourcing, a tendency is then to relax, assuming that what is a good deal now will be a good deal in the future. As cost and technology change rapidly, this is very often not the case.

The question of what value is being added is brought up as an expectation, but not necessarily understood by either the organisation or the vendor. This is not a weakness of IT outsourcing; it is the failure of management to place outsourcing in context with the type of value it can deliver (GartnerGroup 1999a:5).

Expectations by the organisation on assistance by the vendor with technology direction and business IT alignment is huge, which often leads to completely unrealistic or non-defined expectations. Expectation management and user perception's become more and more difficult as operations progress and as the gap between initial user expectations and actual delivery grows. Communication is scaled down as the vendor, and for that matter the organisation, assumes everyone knows exactly what the outsource is about which is a critical mistake as there is normally a constant churn of the people, and the management, that was part of the initial decision, but that might move to different areas or leave the organisation taking the initial contract understanding with them. The same occurs on the vendor side, and slowly the contract starts taking a form of its own, which might have nothing to do with the initial intent of the contract.

It is important during all stages of the execution or operations phase to enforce and adopt formal and detailed governance and operating structures, as this is the only control and audit ability that can be given to the initial contract, and will ensure that the initial intent or changes there-to is well documented and agreed to in a formal forum for future disagreements or disputes. The vendor and the organisation very often neglect governance and end up with disputes due to verbal agreements not being honoured or confusion caused by misunderstanding and no documentation to back decisions or agreements. This leads directly to scope management problems within the contract where verbal agreements are made, and it is assumed that this forms part of the default contract scope. Even though most of the contracts specify a change control procedure, it is very often not enforced or managed formally leading to further scope confusion at later times during operations.

Another essential element that is also not always well thought through is what metrics is to be measured and how these measurements tie in with the service levels the business requires. Without proper measurement elements and targets it is also difficult to actually benchmark the services which creates internal mistrust in the accuracy and market relatedness of the services and pricing being delivered by the vendor. Internal antagonists of the original IT outsourcing decision start to verbalise their original concerns surrounding the outsource contract and internal politics can become rife if not controlled. Gartner (GartnerGroup 1999:6) has found that two years into a deal, organisations are facing:

■ the implications of inevitable post-contract discoveries

■ business units that have forgotten about the deal and just want lower costs

■ difficulties in integrating multiple suppliers or in-house and main vendor teams

■ rapidly changing business requirements

■ difficulty in getting and evaluating vendor proposals for new requirements

■ a contract that is getting significantly out of date

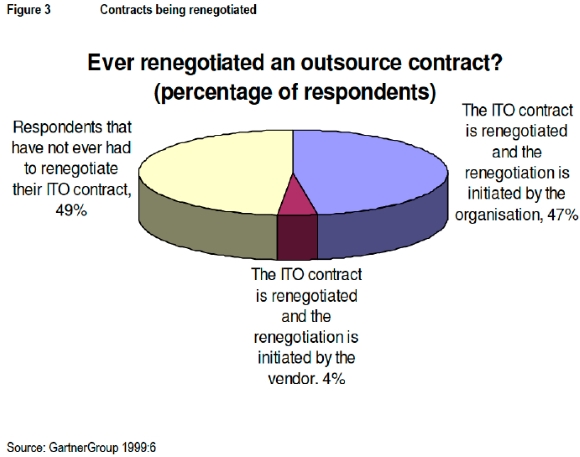

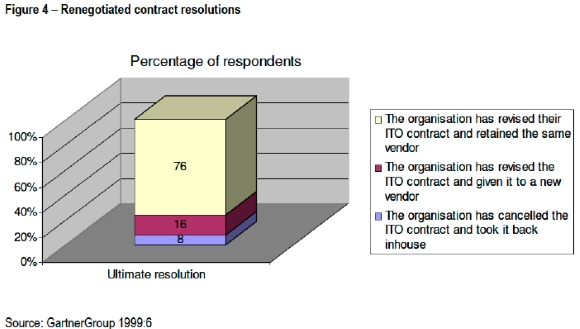

In many cases the problems two years into the execution phase lead to contract renegotiations (formal or informal), as shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, or cancellations due to user disillusionment (GartnerGroup 1999:6).

Figure 3 shows that the most contract renegotiations are initiated by an unhappy organisation and least renegotiations are initiated by the vendor. 49% of respondents have never renegotiated their ITO contracts. For the 49% of organisations that have initiated renegotiations the reasons stem from a lack of proper attention to detail in the initial phases, and stringent governance and control during the execution phase. Many of these problems can be overcome by utilising proper frameworks and doing upfront analysis of what the organisation would like to achieve by outsourcing.

Figure 4 shows that of those respondents that renegotiate their contracts 76% will restructure their contracts and retain the same vendor that they initially started with. 16% of organisations will renegotiate, terminate and establish the ITO contract with another vendor. Only 8% of respondents have terminated their ITO contract prematurely and taken it back in-house.

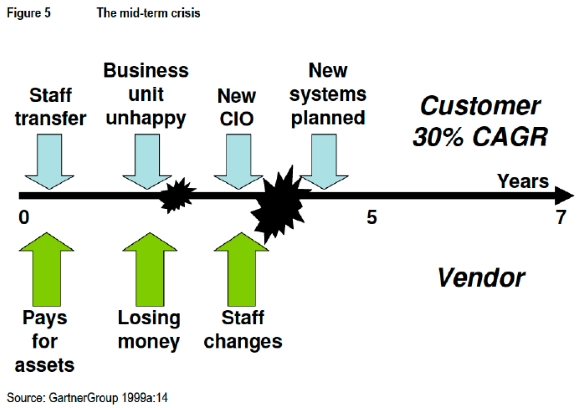

A Gartner example (GartnerGroup 1999a:14) of the mid-term crisis as depicted in figure 5 shows a typical IT outsource contract situation. A large international organisation signs an IT infrastructure outsourcing deal (data centre, network, desktop) on the basis of immediate cost reduction, the purchase of existing assets by the vendor and transfer of IT staff. The contract allows for some changes in usage volumes (e.g., MIPS - million instructions per second processors, disk space, seats). The deal requires heavy financial engineering.

The vendor needs to meet service levels and cut costs dramatically. They plan to break even between year 2 and year 3 of the 7-year deal. One year on, business units have forgotten the deal and want further cost reduction. Contract service levels are being met but the businesses expected more. The corporation is planning to grow at 30 percent per year. Eighteen months on, changes are overwhelming the skeleton staff left in place to administer the contract. The contract is already out of date and the client initiates a benchmark. The vendor is no longer on track to make a profit. Relationships are strained and minor re-negotiations take place to "patch up" the relationship. A new CIO arrives and re-evaluates IT and all existing contracts. The vendor is losing money and key staff are replaced. The contract is now seen as an inhibitor to the organisation's business and business units want to replace the supplier. The supplier has met all the contract commitments. What went wrong? The contract was not structured to meet the changing needs of the business.

TERMINATION PHASE

The last phase is often the most neglected phase in the sense that it is hoped by both the organisation and the vendor that this situation will never be reached where termination has to take place. As such the exact process of termination is not necessarily agreed upfront and an attempt is made during the actual termination to agree a disengagement process. By this time though there are many factors that inhibit defining a fair process as there are often many of the issues lurking as was mentioned in the previous phase discussions.

This often results in dispute around costs, assets and staff that could regress to a state where the vendor refuses to co-operate or buy-in to the termination process which can result in severely disrupted service to the end-users and sometimes have a critical impact to the survival of the organisation.

THE COETZEE SOLUTION FRAMEWORK FOR THE EXECUTION AND TERMINATION PHASES

Execution phase

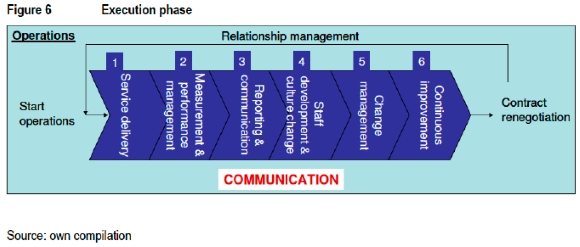

Once transition is successfully completed the official start of operations is declared by both the organisation and the vendor. If the transition set correct expectations and occurred smoothly, then the operations have a good foundation to start with. The operations phase is a continuous cycle of delivery, improvements and change. The business requirements and technology will change over time and this should constantly be revisited to ensure the relevance of the contract.

This phase consists out of a number of activities, rather than specific steps. As such, in Figure 6, the proposed framework is given and described thereafter. The sequence of the steps or activities is not important.

Step 1: Service delivery

This is an ongoing activity that will encompass the day-to-day operations of the ITO. This includes the delivery of the defined services according to the given SLAs and the strict adherence to the contract. The important facet of this step is the consistent high quality delivery and follow-up on commitments given by the vendor staff to the organisation users. Absolute service focus and customer orientation is required by these staff members and the end goals and scope of the contract should be fully understood by all delivery personnel. Constant reinforcement of the contract scope and contract goals should be discussed with the delivery staff and their incentive structures should be aligned to the achievement of these goals. Their individual roles and responsibilities should be defined in detail in the context of the contract to ensure that they understand the part that they play with the associated dependency on them.

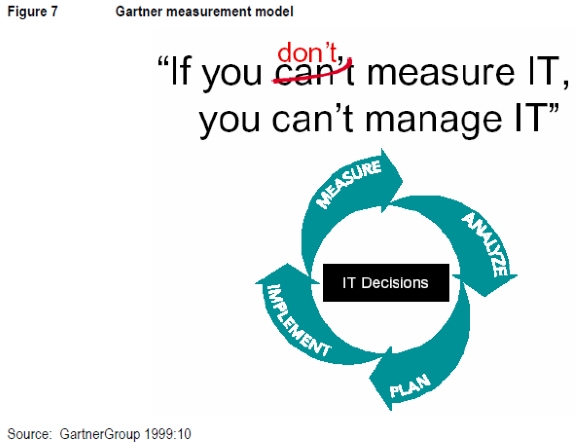

Step 2: Measurement and performance management

This is a critical element to be performed by both the vendor and the organisation. Gartner (GartnerGroup 1999:10) indicates very clearly that if you don't measure IT, then you cannot manage it as illustrated in figure 7.

The measurement criteria, as defined in the contract, should be rigorously updated and the data has to be collected from the start of the contract in order for successful measurement to be possible. The organisation and vendor need to verify the data and ensure that the integrity is always correct (GartnerGroup 1999:11). Proper measurement is the basis for good performance management. Performance management should be implemented at the start of operations and maintained throughout the ITO life cycle. Performance needs to be measured and managed holistically in terms of SLA adherence, people management, customer satisfaction and goal achievement.

Step 3: Reporting and communication

The agreed reports should be generated consistently and the organisation and vendor should jointly evaluate the source data to check integrity and to build a level of trust in regard to the reporting early in the contract. This goes a long way to satisfy the organisation that the vendor is performing according to agreement. Gartner (GartnerGroup 1999:10) says that organisations and their vendors must acquire the monitoring and measurement tools to keep their outsourcing agreements technically and financially on track, and also to demonstrate that they are on track. The reporting must be the basis for constant communication with the organisation users. A regular communication plan needs to be implemented communicating the service performance, SLA achievement, problems, successes, plans and progress against previously set plans. This will control expectation through association with visible proof that the data provided is correct and that plans are delivered on as promised.

Step 4: Staff development and culture change

Attention need to be given to the development of the transitioned staff from all facets: training, education, contract content, methodologies and procedures. The vendor should also consistently reinforce their culture in terms of values and delivery expectations to ensure that the transitioned staff members become part of the vendor culture and community as soon as possible. Rotation of staff to other vendor contracts, or even internal vendor work, should be considered as soon as possible as this expedites the culture change process. These staff members can cause major perception damage in the organisation if they are unhappy as they would typically know many of the influential users in the organisation and discuss the internal vendor issues with these users. The opposite effect is also however true, which is why it is important to have relevant culture change and developmental programmes in place to ensure that all efforts are made to influence the staff positively, which will in turn be felt by the organisation.

Step 5: Change management

Many elements of the service changes during the contract due to technology changes, new business requirements, additional services, revised service level requirements, assets refreshes and many other elements associated with the contract. It is critical to keep track of all these changes and to implement a governance forum to evaluate each of these changes, decide on the financial and service impact, and prepare and sign-off the documentation (change requests) in order to keep a comprehensive audit trail of all changes.

No verbal changes or agreements should be acted on in order to prevent setting a precedent of any sorts. This is one of the downfalls in many contracts as both parties view it as a nuisance and want to operate on a gentleman's agreement basis. This works well until something goes wrong, then it becomes the reason for many disputes and vagueness in scope.

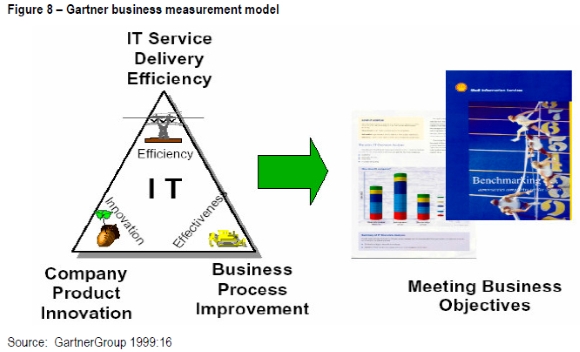

Step 6: Continuous improvement

Continuous improvement is something that must be a constant priority as this is where the vendor adds additional value to the customer and ensures the business relevance of the contract remains. Many ITO contracts are questioned due to the lack of business benefit or business alignment, so every effort should be made to look at all aspects of the contract continuously to ensure relevance and suitability. Gartner (GartnerGroup 1999:16) has found this fact in their research as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8 shows that the most contract renegotiations are initiated by an unhappy organisation and least renegotiations are initiated by the vendor. 49% of respondents have never renegotiated their ITO contracts. For the 49% of organisations that have initiated renegotiations the reasons stem from a lack of proper attention to detail in the initial phases, and stringent governance and control during the execution phase. Many of these problems can be overcome by utilising proper frameworks and doing upfront analysis of what the organisation would like to achieve by outsourcing.

Contract renegotiation should not be seen as a threat by the organisation or vendor as technology evolution and changes in the business environment forces constant renegotiations and revisiting of the foundation and vision of the ITO contract to ensure relevance and acceptance.

Contract renegotiations should be a permanent agenda item when the contract strategy is reviewed or discussed. This will give both parties the comfort that the benefits are understood and relevance is maintained. It also shows goodwill. Gartner (GartnerGroup 1999a:8) says that contract renegotiations in the IT outsourcing market are becoming commonplace. This trend is not only driven by an increasing number of agreements approaching the end of their term; it is equally a reflection of the complexity of outsourcing deals coupled with the pace of business change and IT development.

It is important to note that throughout the operations phase meeting SLAs does not equal satisfying the organisation. Outsourcing vendors must consider the broader aspect of the customer relationship, including careful listening, prompt follow-through on commitments, and ensuring that a true partnership model is the basis for the agreement (Harris 2002:30).

Termination phase

Termination normally occurs for one of two reasons:

■ the contract has reached its end naturally and the organisation does not wish to renew or to give it to the same vendor again

■ the organisation and vendor has reached an impasse in terms of relationship, service issues, business benefit or contract relevance

The natural closure of the contract means that both parties part on a fairly good standing in terms of relationship and as such the termination is normally easier. The second reason however is normally hostile and can involve arbitration or even legal action. In this situation the termination is very difficult with little cooperation from both parties and a complete breakdown in trust. Professionalism and maturity is required to enable the organisation, and for that matter the vendor, to survive the termination and not cause major business disruption.

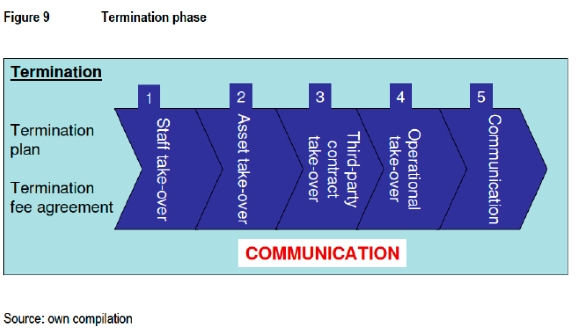

Notwithstanding the reason the following are the activities that should take place surrounding the termination. The proposed framework is depicted in figure 9. The sequence of these activities is not important.

These steps are in essence the same as the transition model, but reversed between the organisation and vendor. Depending on the state of the asset register and the audit trail of the technical environment and the level of the organisation involvement in the management of the contract, it is sometimes recommended to do a reverse due diligence process where the organisation fully evaluates the environment that they will be taking back.

It is important for both parties to jointly define the termination plan to ensure cooperation. The termination fees also have to be agreed before the termination begins to ensure that there is no dispute regarding this during the termination handover. The termination fees are normally a formula based on asset value, staff costs, service time, third party contract termination penalties, legal fees, forward profits and overheads.

The activities, as per figure 9, are:

Step 1: Staff take-over

In some cases the contract allows for staff utilised on the contract at the time of termination to be transferred from the vendor to the organisation. Once again this involves a full benefits, incentives and staff position mapping.

Step 2: Asset take-over

Some contracts allow for the assets to be bought back by the organisation. This can be a disruptive exercise if agreement cannot be reached on the assets required for the organisation business continuity.

Step 3: Third-party contract take-over

The third parties used by the vendor should either be transitioned to the organisation or the vendor should assist the organisation in setting up new contracts to ensure unbroken service continuity. The full extent of the third party contract terms and conditions should be understood as this normally forms part of the termination calculation. The organisation should fully understand the services that are being delivered by the third parties and the impact it would have to cancel versus cession of these contracts.

Step 4: Operational take-over

Here the services are transitioned back to the organisation. Care should be taken to understand all the shared infrastructure and technology that the vendor utilised to get economies of scale between its contracts. This can amount to a costly investment for the organisation to recreate these shared services if the technologies or shared staff were not included in the termination deal.

Step 5: Communication

Communication should intensify on the part of the organisation to keep users pacified in that major service disruptions will not occur and what the plans are to ensure this. This will give comfort and assist in cooperation by all to ensure a smooth termination.

Termination need not be complex if an agreed plan is developed and disputes are handled according to the original contract termination process definition. The termination to a large extent depends on the maturity by which both organisations are approaching the issues. The vendor should at all costs ensure a smooth termination as this ensures good market perception for future deals. The organisation should assist in this process.

CLOSURE

The execution or operations phase of the contract is one where user perceptions start dropping due to unfulfilled expectations. The constant churn of staff and management in both the organisation and vendor often clouds the original intent of the contract. The mechanisms to manage the execution phase is all about formal governance, managing change, developing staff, measuring service and improving efficiency, and continuous improvement to adapt the changes in technology and business requirements.

The termination phase is dependent on having a proper termination mechanism agreed during the due diligence and contracting phase and is further dependent on professionalism and maturity to enable the organisation, and for that matter the vendor, to survive the termination and not cause major business disruption. In essence the termination is a reverse transition process from the vendor to the organisation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Note: The Gartner research group consist of a number of companies that focus on various areas of the market. Gartner DataQuest is the information technology research company within the group. The GartnerGroup general conference papers are normally produced on behalf of the entire group of Gartner companies and not in terms of specific authors. Gartner further produces various research reports which are written by specific authors.

CASALE F. 2001. IT outsourcing: the state of the art. The Outsourcing Institute. October. [ Links ]

GARTNERGROUP. 1999. Managing outsourcer relationships. GartnerGroup conference presentation. November. [ Links ]

GARTNERGROUP. 1999a. Making the decision to outsource. GartnerGroup conference presentation. November. [ Links ]

HARRIS M. 2002. Network outsourcing: lessons from state government. Gartner focus report. 3 May. [ Links ]

SIEMENS BUSINESS SERVICES. 2003. Outsource framework. Outsource reference for customers. [Internet: http://www.siemens.com/index.jsp?sdc_p=i1026935z3lo1046283t4u2mcdn1045363s3fp&sdc_sid=6951080468&. January. [ Links ]]

SIMMONS. 2004. The outsourcing life-cycle: 9 stages. [Internet: http://www.corbettassociates.com/firmbuilder/articles/19/48/945/. [ Links ]]