Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.2 no.1 Meyerton 2005

RESEARCH ARTICLES

New project management techniques: using the entrepreneurial mind

R MacDonaldI; J MalanII

ISiemens

IIImbisa

ABSTRACT

Project management has to forecast the market needs and demands for better and ever improved practises. These demands are grown primarily out of the uniqueness of projects. This paper reviews entrepreneurial concepts in the learning organisation and the new business venture, both technically and characteristically.

The intention with the paper is to generate ideas, styles, techniques and possible new methods of project handling, execution and control. These concepts are sourced from entrepreneurial values and methods both implemented and researched over the past fifteen years. Methods of communication and influence as well as knowledge transfer and knowledge sharing are explored purely for the purpose of thinking about project management, outside of the box.

Key phrases: entrepreneurship, management technique, project entrepreneurship, project management

INTRODUCTION

Bourne & Walker (2004:226) describe traditional project management as skills that were developed from the requirements of construction and defence industries to plan, control and manage large, complex "tangible" projects. From these industries arose the so-called "hard" concepts of project success criteria, in the form of controlling and managing schedule, cost and scope.

Project management can also be seen as being about managing change (Cleland 1995:82), and therefore project managers could consider themselves as change agents adding to the project management role an additional focus on the so-called "soft" aspects of relationship management. The relationship management role is particularly relevant when considering non-traditional, non-construction projects, delivering "intangible" results, such as those in the sphere of business process change.

Project management, whilst having a traditional base, will forever be exposed to the need for contemporary ideas and techniques. This is due to the uniqueness of projects and the forever changing setting in which they are executed. This paper reviews two settings in which projects are executed; firstly the learning organisation and secondly the new business venture.

In the first (the learning organisation), current research will be scrutinised for new ideas relating to the field of project management including innovative concepts and strategies.

In the second (the new business venture), entrepreneurship will be studied and entrepreneurship creation models will be analysed in an effort to discover mechanisms that would foster different project management styles and techniques.

THE LEARNING ORGANISATION

A learning organisation is defined by Johnson & Scholes (1999:83) as being an organisation capable of benefiting from the variety of knowledge, experience and skills of individuals, through a culture which encourages mutual questioning and challenge, around a shared purpose or vision.

Bourne & Walker (2004:233) describe a process of tapping into the power lines. It is set in an environment where project managers in large, learning organisations have responsibility and authority for managing schedules and costs but rarely have a sufficient level of authority to manage all aspects of the project. The power base of the individual project manager depends on the perceived importance of the project as well as their reputation and influencing skills. "Knowing which styles of persuasion to use and when depends to large extent to the political skills and courage of the particular project manager" (Lovell 1993:73). None of the project managers described in their case studies was able to operate effectively within the power structures of the organisation surrounding the project. Even those who recognised that such engagement was necessary could not achieve their objectives.

The key to surviving (and thriving) within an organisation's power structure appeared to be building and maintaining robust relationships. Bourne & Walker (2004:226) claim that it is dangerous to ignore the effect of "politics" on the outcomes of a project. It is important to understand how the patterns of political activity operate in any particular organisation. It is also important for a project manager to understand how they react to these situations and if necessary adapt personal behaviours to ensure success. The emphasis must be on striking a balance between left-brain and right-brain activities, that is, development of deliberate rational thoughtful strategies as well as developing an empathetic relationship with influential project stakeholders.

Understanding the power environment of the organisation and the position of the actors within it for each particular issue is also crucial (Lovell 1993:73). With experience, this understanding becomes a combination of conscious and intuitive, almost instinctive, thought processes leading to actions. This sounds deceptively simple, but requires knowledge of the environment and all the "players" in the process and what their drivers (needs and wants) are. According to Bourne & Walker (2004:234), failure to understand and control the political process has been the downfall of many good projects. To manage successfully within an organisation's power structures it is necessary to understand the organisation's formal structure (an organisation chart should illustrate this), its informal structure (friendships, alliances)n maintaining acquaintance with former work colleagues and its environment (each player's motivation, priorities and values).

Communication is a vital tool for project managers to develop and maintain robust and effective relationships with stakeholders within all three organisational structures. The power structures surrounding a project (the power grid) are complex and constantly changing and require a high level of maintenance. Active communication, including sharing access to the "grapevine", is more easily accomplished sidewards with the project manager's peers. This is done mostly in the informal organisational structures through meetings, telephone calls and perhaps regular (even if infrequent) coffees.

Maintaining communication and tapping into the power lines in an upwards direction, is a great deal more difficult, but not impossible and is generally in the domain of the formal organisational structure with elements from the organisational environment described above. Regular project updates and formal project communications and presentations to influential senior stakeholders and effectively managed governance meetings are formal means. Other effective upwards communication techniques require knowledge of the organisation and product offerings and exploiting the "grapevine". Inevitably, "rogue" stakeholders (supporting one of the conflicting parties, or seeking to establish ascendancy over other stakeholders, or with other hidden agendas) will incite conflict or cause trouble for the project manager. This trouble can come in the form of seeking to cancel the project or change the scope or technical direction of the project. If the project manager has established credibility, disaster may be averted. To establish credibility, the project manager must build the appropriate power and influence foundations by involving all relevant stakeholders throughout the project and maintaining them with active communication systems.

Bourne & Walker (2004:235) list danger signals which a project manager should look out for in avoiding possible trouble with senior stakeholders:

■ interfering without consultation

■ not providing support when needed.

■ poor communication links - too many reporting levels between the project manager and the senior stakeholder.

■ unfounded promises or commitments.

Only a project manager who has built credibility, and knows how to tap into the power structures of his/her organisation can recognise these signs, and defuse potential crises before disaster strikes. Bourne & Walker (2004:235) conclude that the qualities and actions that make a good leader coupled with the third dimension wisdom and know-how, will support a project manager working successfully within the power structure of an organisation to maintain the objectives defined by the project vision and mission.

ENTREPRENEURIAL KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

In most organisations today, where competitive advantage is tied to swift, effective development of products or services, projects are generally the mechanisms of this delivery. Organisations can no longer afford the luxury of allowing a project manager's knowledge and experience to just evolve naturally. They must always be aware of the need to act to ensure that an individual's knowledge becomes part of an organisation's knowledge and that the organisation's knowledge is accessible to each individual, Bourne & Walker (2004:237).

Bhatt (2002:33) argues that although an organisation has access to an individual's skill and knowledge, it can never own that individual's knowledge, Bhatt states: "On

the contrary, the organization itself becomes vulnerable to the mobility and idiosyncrasies of experts... What kind of knowledge is shared is determined by the professionals, not the management... Knowledge sharing is an informal and social process"

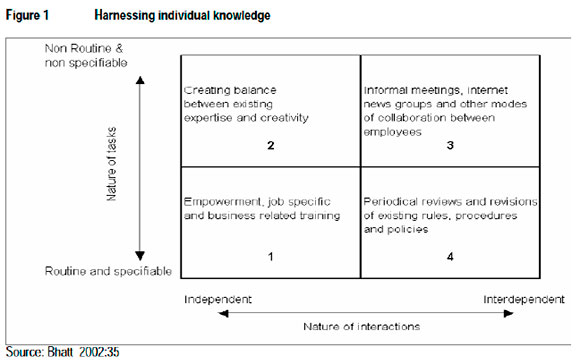

The social process is facilitated by "interactions", and the organisation must do everything possible to ensure these interactions take place. Figure 1 shows how organisations can harness individual knowledge through an understanding of the nature of interactions. Each cell represents a mode of learning that is important.

Cell 1 focuses on individuals performing routine, low interaction tasks. The challenge is to empower employees by providing guidelines for limited discretion in daily routine tasks. These employees can be trained to understand the hidden realities of "doing business in the present dynamic and competitive environment" (Bhatt 2002:35). In the context of the development of project management wisdom, this applies to the project manager in the novice to junior project manager classification.

Cell 2 defines the approach for managing individual expertise. These individuals must be motivated through "stretch" assignments, accompanied by appropriate strategies for support and reward. The challenge is to "balance the needs of the organisation (for greater productivity and effectiveness) with the desires of experts for exploration of new ideas" (Bhatt 2002:36). This approach applies to project managers at any level, but primarily to those who are more experienced, from fully accredited upwards.

Cell 3 describes mechanisms forknowledge sharing through social interactions. These mechanisms include self-managed teams brought together for a specific purpose, and Communities of practice - usually voluntary, informal guilds. However, irrespective of how the groups come together, the essential elements of success are trust, commitment, collaboration and a shared vision.

Cell 4 describes the challenge of storage and codification of rules and procedures.

Cohen & Levinthal (1990:128) describe an organisational characteristic they refer to as "absorptive capacity" - the capacity of an organisation (or individual) to absorb new knowledge. The most important factors of absorptive capacity are cultural - such as openness, tolerance of mistakes, cultural diversity of participants in terms of their world-view, and freedom to experiment with new ideas.

Perhaps absorptive capacity can be used as a measure for a project manager's ability to use entrepreneurial techniques and other new ideas for project control and coordination.

THE NEW BUSINESS VENTURE

According to Moon (1999:31), the term "entrepreneur," coined by Richard Cantillon and later popularised by French economist JB Say in the early 1800s, originally referred to "merchant wholesalers who bear the risk of reselling agricultural and manufactured produce" (Baumol 1993:12). Later it represented the individual who "shifts economic resources out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield" (Drucker 1985:21). In the public sector, meanwhile, entrepreneurship often represents "public enterprise," a hybrid of public and private organisations that is considered to be a more efficient organisational form for some government programmes (Thomas 1993:474).

In Moon's 1990-paper on managerial entrepreneurship, the terms contractual entrepreneurship and managerial entrepreneurship are discussed.

■ Contractual entrepreneurship describes market-based government activities that attempt to introduce market competition and promote contractual relationships in the public sector. Contractual entrepreneurship includes government franchises, privatisation, cross-services, and contracting out.

■ Managerial entrepreneurship broadly refers to managerial as well as properties that promote innovations and changes that improve performance with respect to organisational products, processes, and behaviours. Managerial entrepreneurship has been explored under various theoretical frameworks.

Three dimensions of managerial entrepreneurship

Moon's paper (1999:32) suggests that discussions of entrepreneurship have extended to many disciplines such as psychology (in articles by Shaver & Scott 1991:23), sociology (Reynolds 1991:47), economics (Kirchhoff 1991:93), marketing (Hills & LaForge 1992:33), finance (Brophy & Shulman 1992:61), and strategic management (Sandberg 1992:73). Each discipline has developed its own unique interpretation of entrepreneurship and focused on its own unit of analysis. For instance, psychology emphasises the individual as its unit of analysis. It applies social cognitive theory and expectancy theory to explain entrepreneurial personalities and behaviours (Shaver & Scott 1991:23). Marketing pays attention to new ventures and new products in an uncertain environment. It closely examines customer satisfaction and the relationship between marketing activities and human behaviours with commercial products (Hills & LaForge 1992:33). Sociology examines relationships such as social networks, individual life course stages, and other social factors to explain the causes and nature of entrepreneurship (Reynolds 1991:47).

The interdisciplinary concepts of entrepreneurship with different foci have recently been applied to the public sector for managerial improvement. Moon (1999:31) reports on ten principles by Osborne & Gaebler, which they believe are the foundation for entrepreneurial government. The literature on entrepreneurship largely agrees that the concepts and theoretical constructs of entrepreneurship are multi-dimensional (Hofer & Bygrave 1992:91).

Moon (1999:32) proposes three different dimensions for managerial entrepreneurship: product-based entrepreneurship, process-based entrepreneurship, and behaviour based entrepreneurship.

■ Product-based managerial entrepreneurship emphasises the quality of the final outcome (product or service) that an organisation produces. One indicator of product-based entrepreneurship is the level of customer satisfaction.

■ Process-based managerial entrepreneurship refers to the improvements in administrative procedures, intra-organisational communications, and intra-organi-sational interactions. Literature strongly suggests the importance of flexible decision-making processes, open communication, and simplification of the work processes in organisational innovations (Stupak & Garrity 1993:3; Swiss 1992:356). As Swiss (1992:356) points out, organisational outcome is closely associated with organisational processes because it reflects the way in which internal and external decisions are made and how resources are utilised in organisational functions. One indicator of process-based managerial entrepreneurship is the level of red tape in organisations. Red tape has been addressed as an example of a pathological organisational process that demotes fair and equal treatment and leads to administrative delay and miscommunication among sub-units (Bozeman 1993:273).

■ Behaviour-based managerial entrepreneurship refers to the propensity for risk-taking. Risk-taking here is a strict managerial term discussing the propensity for organisational change and innovative decision-making. Sanger & Levin (1992:88) find that "... innovative public managers are entrepreneurial: they take risks ... with an opportunistic bias toward action and a conscious underestimating of bureaucratic and political obstacles their innovations face". Entrepreneurship is often regarded as opportunity-seeking activities rather than risk-taking activities (Drucker 1985:21). But the pursuit of opportunity is certainly associated to some extent with risk-taking behaviour because uncertainty is embedded in the opportunity.

BUSINESS START-UP ENTREPRENEURIAL SKILL

With a focus on all dimensions of managerial entrepreneurship, the new business venture entrepreneur can be explored for new project management skill.

Klandt (1993:44) in a review of his collaborative and edited writings, finds that the ideas of the entrepreneurial manager dominate strongly the choice of strategy, organisational form, and other major decisions in small businesses. In Klandt's previous research it has been found that the entrepreneurs usually aim to create either a very big successful firm or a small firm. A small firm is easier to manage and simple in its operations. It seems that the main motive for creating one's own firm is to seek autonomy and personal freedom. Also; self-fulfilment, achievement, pride of craftsmanship, money etc. are among the most often mentioned positive arguments for entrepreneurship. There is also much entrepreneurship, which has been started to avoid unemployment or other negative imperatives.

Klandt goes on to report in an article by Huuskonen (1993:46) The most important personality factors in the entrepreneurship literature are:

■ Locus of control. It has been generally believed that entrepreneurs have exceptionally strong feeling of being masters of their own destiny (Internal locus of control).

■ Need for achievement. Need for achievement is the striving force behind entrepreneurs. It has been thought that entrepreneurs differ from other groups in this sense. In consequent studies this has not been proven. Entrepreneurs are high in need for achievement, but so are many other groups as well (e.g. managers)

■ Attitude to risk. Entrepreneurs have often been regarded as apt risk-takers. Later findings prove that they are neither seeking for small or big risks. They resemble more or less the general population.

■ Need for autonomy and need for power. It is important for the entrepreneurs 'to be one's own boss'. They have also been characterised to be difficult and rebellion personalities, who cannot adapt into a normal working environment. Therefore they have to tailor a suitable job for themselves.

■ General attitudes and values. Attitudes or values are not direct causes for entrepreneurship by themselves, but they affect perception and different reasoning processes.

BUSINESS START-UP TECHNOLOGY BASED ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Zahra & Hayton (2004:186) report on key themes and emerging research direction in technology-based entrepreneurship. They state that research on technological entrepreneurship has increased significantly over the past three decades, reflecting three important trends.

The first trend is the increased recognition of technology as a key driver of change. Researchers, managers and public policy-makers have become aware of the crucial role of technological forces in creating discontinuities that unleash gales of creative destruction in the form of innovation. Innovation, in turn, creates new companies and industries that generate wealth for the founders and society at large. The rules of competition in these industries are not well defined, and societies compete to position themselves as the pacesetters of global technological standards. Countries that succeed in establishing global standards can dominate the growth and evolution of these industries over the next few decades and as result create greater wealth for their citizens. Technological changes not only creates opportunities for wealth creation, but also displaces citizens and alters the fabric of a society, compelling public policy makers to be proactive in shaping the evolution of new industries. The second trend in the literature is the recognition of the role of technology as a source of organisational competence. Competencies are the set of skills necessary to develop the capabilities that give companies the advantages over their rivals. Technology serves as a lever that organisations can use to cultivate other resources by combining them to generate new strategic weapons. Technological changes make traditional competencies less relevant and pressure companies to rethink how and where they compete, creating additional] opportunities for entrepreneurial activities within established companies and by individual entrepreneurs.

The third trend in the literature is the growing recognition of the importance of technology commercialisation forvalue creation. Concern persists that US companies have not done well in cultivating the fruits of their inventions. Many US companies excel in creating technology but do not do as well in taking these technologies to the market. The same observation applies also to universities. Leading research universities have created innovations, but many of these innovations have not been commercialised. This has deprived universities from a major source of revenue. While these challenges are universal, US universities need to commercialise their discoveries in order to offset declining state and federal support of higher education and to generate the funds necessary to support new academic programs and attract star researchers and graduate students.

CLOSURE

Entrepreneurs and or entrepreneurial skill are often characteristics of personality or traits and could be considered for their value in determining new project management practices. However, key practises can be derived from the following entrepreneurial trends in technological entrepreneurship:

■ the increased recognition of technology as a key driver of change.

■ the recognition of the role of technology as a source of organisational competence.

■ the growing recognition of the importance of technology commercialisation for value creation.

Bourne & Walker (2004) have an important message that is drawn primarily from the nature of entrepreneurship: the power base of the individual project manager depends on the perceived importance of the project as well as their reputation and influencing skills.

Ultimately a lesson from the learning organisation is based on communication via social processes which are facilitated by "interactions", and the organisation must do everything possible to ensure these interactions take place. Ultimately, new project management techniques will evolve as a matter of necessity, but the earlier they are anticipated and implemented the more successful project managers can be.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BAUMOL W. 1993. Entrepreneurship, management, and the structure of payoffs. Cambridge: MIT. [ Links ]

BHATT G. 2002. Management strategies for individual knowledge and organizational knowledge. Journal of Knowledge Management, 6(1): 31-39. [ Links ]

BOURNE L & WALKER D. 2004. Advancing project management in learning organizations. The Learning Organization, 11(2/3): 226-243. [ Links ]

BOZEMAN B. 1993. A theory of government red tape. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 3(2): 273-303. [ Links ]

BROPHY D & SHULMAN J. 1992. A finance perspective on entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(3): 61-71. [ Links ]

CLELAND D. 1995. Leadership and the project management body of knowledge. International Journal of Project Management, 13(2): 82-88. [ Links ]

COHEN W & LEVINTHAL D. 1990. Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1): 128-152. [ Links ]

DRUCKER P. 1985. Innovation and entrepreneurship. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

HILLS G & LAFORGE R. 1992. Research at the marketing interface to advance entrepreneurship theory. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(3): 33-59. [ Links ]

HOFER C & BYGRAVE W. 1992. Researching entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(3): 91-100. [ Links ]

HUUSKONEN V. 1993. Entrepreneurship and business development: the process of becoming an entrepreneur. Vermont: Ashgate. [ Links ]

JOHNSON G & SCHOLES K. 1999. Exploring corporate strategy. 5th ed. Hertfordshire: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

KIRCHHOFF B. 1991. Entrepreneurship's contribution to economics. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice., 16(2): 93-112. [ Links ]

KLANDT H. 1993. Entrepreneurship and business development. Vermont: Ashgate. [ Links ]

LOVELL R. 1993. Power and the project manager. International Journal of Project Management, 11(2): 73-78. [ Links ]

MOON M. 1999. The pursuit of managerial entrepreneurship: does organization matter. Public Administration Review, 69(1): 31-55. [ Links ]

REYNOLDS P. 199 . Sociology and entrepreneurship: concepts and contributions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(2): 47-70. [ Links ]

SANDBERG W. 1992. Strategic management's potential contributions to a theory of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(3): 73-90. [ Links ]

SANGER M & LEVIN M. 1992. Using old stuff in new ways: innovation as a case of evolutionary tinkering. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 11(1): 88-115. [ Links ]

SHAVER K & SCOTT L. 1991. Person, process, choice: the psychology of new venture creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(2): 23-45. [ Links ]

STUPAK R & GARRITY R. 1993. Change, challenge, and the responsibility of public administrators for total quality management in the 1990s. Public Administration Quarterly, 17(1): 3-9. [ Links ]

SWISS J. 1992. Adapting Total Quality Management. Public Administration Review, 52(4): 356-362. [ Links ]

THOMAS C. 1993. Reorganizing public organizations: alternatives, objectives, and evidence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 3(4): 457-486. [ Links ]

ZAHRA S & HAYTON J. 2004. Crossroads of entrepreneurship _ Technological entrepreneurship: key themes and emerging research directions. Boston: Kluwer. [ Links ]