Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.2 no.1 Meyerton 2005

RESEARCH ARTICLES

How to deal with cultural differences as a project manager

Lenny Dunmark

Jönköping International Business School, Sweden

ABSTRACT

The world is becoming increasingly smaller and there is an aggregated need to perform cross-culturally. All sorts of organisations are facing new problems relating to a shift in focus more towards an international and cross-cultural perspective. To achieve a satisfying result when managing projects in a culturally foreign environment requires preparation and knowledge.

The aim of this paper is to point out certain things to be aware of when taking on a multi-cultural project, as well as giving some examples of strategies to use. By doing so, give answers to the question of how to effectively and efficiently manage projects that take place in a multi-cultural environment.

Managing a project in a cross-cultural environment make the project more complex, however, there are various benefits to be reaped from taking advantage of the inputs of different cultures. To do so the Project Manager must keep an open mind and be aware of the differences. Failure to pay attention to foreign cultural behaviour could end the even best of projects permanently.

There is a surprising lack of research in the field of cultural differences within the field of project management. This paper is an attempt of compiling an initial overtaking to the subject

Key phrases: communication strategies cross-cultural, cultural differences, communication, project management

INTRODUCTION

The way business is conducted has changed during the past years. Today an increasingly amount of work is being carried out cross-borders and many multicultural teams are being formed (Black & Mendenhall 1990:114). Working in a foreign environment will challenge everything the Project Manager culturally has taken for granted. There is a risk for experiencing a "culture shock". It is crucial for the success of the project that the Project Manager is aware and prepared for this. There are several things to take into consideration, but a piece of advice that will be valuable for the Project Manager is not to be afraid of asking questions to get acquainted with cultural behaviour. Asking questions to the host or business contacts can reveal basic things that can prove useful. Even the most trivial issues can grow into major obstacles (Heldman 2004:419).

Despite being a major issue for many companies, there is a lack of research in the field managing a multi-cultural project. Compared to other aspects of project management, this area seems to have been neglected in the literature (Shore & Cross 2005:1). Since this topic carries such a relevance to many organisations, it would benefit from further research. There is a need for more research.

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

Cultural differences are something not only to be found and experienced when travelling abroad, cultural differences can also appear at the office. This is something to be attentive of. Well managed cultural differences can become something the company and the project can benefit from. However, failure to see and recognize cultural differences may jeopardize the best of projects.

Definition of culture

What culture is can be really difficult to answer but it is clearly something that is established early in the mind of the individual. These first impressions on how to behave in certain situations can be very hard to change later on. Culture can also not be described with words; a culture needs to be experienced. It is very seldom that a person fully understands just how much he or she is influenced by the culture until the granted assumptions that come with it are challenged (Shore & Cross 2005:4).

Culture dictates how we perceive the world and people around us; it decides how life is organised and holds a group of people together. The culture has nothing to do with genes but is strictly based on upbringing and the social environment. The basic line of culture is about shared values and meanings (Black & Mendenhall 1990:121; Hoecklin 1995:25-26; Simmons 2002:33).

Being a Project Manager brings along a challenge to the leadership, being in charge of a multi-cultural team or working in a multi-cultural environment creates even higher demands on the leadership (Màkilouko 2004:4). The unfamiliarity feeling that emerges from working in an unfamiliar environment can create stress for both the team members and the Project Manager. It is especially important for the Project Manager to be able to have the emotional capacity to cope with the stress; if the Project Manager is not able to handle this additional factor of stress, it would be difficult to guide the team through the stress that will evolve due to the confusion and insecurity (Black & Mendenhall 1990:117; Màkilouko 2004:5).

Planning a multi-cultural project is very similar to planning an ordinary project, the process of Initiation, Planning, Executing, Controlling and Closing must be done. However, a multi-cultural project is much more complex since it requires so much more coordination; and the input from the different cultures involved makes the process even more different and difficult to manage (Shore & Cross 2005:2).

The best saying in the literature concerning managing a cross-cultural project is "The secret of managing and operating internationally or cross-culturally is not to be a stranger" (Fogel 1998:1). As a Project Manager working in a cultural diversified environment it is vital to be able to put everything in order, and to do so the Project Manager needs to be aware of the differences.

The only way to really know differences is to actually experience them. Cultural differences and the way they are handled can be the difference between success and a failure of a project. Therefore it is of the highest importance that the Project Manager is aware of that fact and act accordingly. There are numerous examples of experienced Project Managers that have ended up with problems when managing projects in a foreign country or with a team consisting of people from various cultures. In spite of this, there are also examples of well-managed projects that have turned cultural differences into an advantage (Ramaprasad & Prakash 2003:4).

Multi-cultural teams

There exist three different basic forms of multi-cultural teams.

■ Firstly, there is the project team consisting of team members with different cultural backgrounds working in the same region.

■ Secondly, there is the team consisting of people from different backgrounds where the team is scattered over the world but meet face-to-face on a regular basis.

■ Finally, there is the dispersed team that hardly or never meet face-to-face but work together through electronic media such as phone conferences and email.

Meeting the team members is naturally a benefit since it is easier to form personal relationships, something that will improve communication and diminish misunderstanding and conflicts (Mäkilouko 2004:4).

Communication

The best example to be found in literature about unsuccessful projects is the story of the tower of Babel, where the people were determined to build a tower to reach the sky but failed due to the language barrier (Fogel 1998:1).

Just the fact that people speak different languages would not be too much of a problem; a new language can be learned relatively easily. On the contrary, the problem is rather to master the use of the silent language such as body language and also to understand the meaning of words used. The way the word is being pronounced can say more than the actual word. For example the word "ishi", which is commonly used in Ethiopia, can mean such various things as "okay" or "leave me alone" (Fogel 1998:1). If the Project Manager is not aware of how the word is used he or she will not fully benefit from speaking the language. Same phenomena can be experienced in the Chinese language Cantonese where each word can be pronounced in up to nine different tones all with different meaning (Campbell 2004:Internet).

Body language makes up 55 to 80% of how we communicate; therefore it is important to be aware of differences in usage of body language (Andila 2005:Internet). How we shrug our head when answering a question can differ from a nod for yes and a shrug for no. There are also many different ways we use our hands to accentuate what we are saying when we talk. We all know that people with a Latin heritage are more keen on expressing themselves using hand movements and their body to further clarify what they are saying, while the British are known to be able to speak without hardly moving a muscle (Milosevic 2002:5).

Initiating a conversation gives rise to another issue, how to handle the issue of personal space? How much physical distance is appropriate to keep when having a conversation? Each culture has their set of accepted distances, which are important to respect in order to not make the other feel uneasy (Fogel 1998:3).

The start of a project often involves negotiations between the different stakeholders. The negotiations themselves poses problems but another problem comes first, that is how to greet people you will negotiate with (Fogel 1998:2) Is a sturdy handshake enough, or are you required to engage in a three-phase handshake, or will there be a kiss on the cheek (Fogel 1998:2)? Remember that the first impression last!

A simple thing that can become a major annoyance is whether or not to look the counterpart in the eyes when talking. Certain cultures consider it to be polite to establish eye contact when speaking while others may take this as a serious sign of hostility or a threat of authority.

Since one of most important skills of the Project Manager is his or her ability to communicate, it is very important to stress that the Project Manager must be aware of the differences in the way different individuals communicate. The key to success is to never be afraid of clarifying things, for example, use both numbers and letters to spell the amount discussed. Simple techniques will carry the Project Manager far, such as a white board to put up facts that have been decided (Brown 2003:Internet).

Time

Time is another aspect that can make the most experienced Project Manager frustrated when trying to complete a project in a foreign environment. First problem is when to show up for an appointment. It is not always clear if the appropriate thing is to show up early or late. Germans have a reputation of being very precise and punctual while other nationalities are known to have a different approach to an appointment.

Time does not only involve the actual time seen on a wristwatch when rushing to a meeting. Time is also measured in days, weeks and month. Many people in western cultures take for granted following the Gregorian calendar; however many cultures are instead basing their perception of time on the Lunar calendar which varies more than the Gregorian calendar (Fogel 1998:2; Ramaprasad & Prakash 2003:5-6).

When managing a project, for example in India or other parts of Asia, it is important to take into account both ways of keeping track of the days. Using two different calendars bring the problems of having to deal with even more sets of non-working days. Just using the Gregorian calendar will bring many different days which are considered to be inappropriate for work. The easiest example is Sundays for Christians and Saturdays for Jewish people. Most people have heard of the Moslem tradition with the Ramadan, the month-long fasting period where certain rituals are being carried out. Many Catholic countries also celebrate several saints' days. All these days may be fluctuating from year to year and from geographical places all according to various variables (Fogel 1998:2; Ramaprasad & Prakash 2003:5-6). In order to be aware of all important days the Project Manager needs to be very familiar with the specific traditions of the culture he or she are working in or with. Failing to respect important days can be a major mistake that can bring the project past the point of repair.

Contacts

In many places around our globe it is custom to get to know each other, gaining the trust necessary to conduct business or start up a project. The process of getting acquainted can take several days where there is hardly any talk relevant to the project. A Project Manager operating away from home should not be surprised when being invited to take part in family gatherings and the like. This is part of the process of forming a long term business relationship and if well managed this can be of great benefit. This may feel awkward for a Project Manager used to the customs of the USA, for example, where it is down to business more or less instantly.

When it comes to the actual negotiations the Project Manager must be aware that different cultures have different perceptions on how the negotiations are supposed to be carried out. In many cultures who you are talking to is of great importance, Japanese for example are very focused on seniority. Also contracts are regarded differently in various cultures. To stick to the Japanese example, the Japanese consider a contract to be a start of negotiations, not the final output. The Japanese are also not people of conflict but rather people that seeks consensus and are very concerned not to lose face. The Project Manager must be attentive to this in order to succeed in negotiations (Fogel 1998:2).

MANAGING A CROSS-CULTURAL PROJECT

A Project Manager managing a cross-cultural project faces a challenge, not only does he or she need to manage the project, like any project, the Project Manager is also required to take further details into consideration in order to succeed.

Organising

Having managed all the basic things it is time to start organising the project and the team itself. How to organise and delegate can be difficult when working with different cultures. One thing to take into account for the Project Manager is how people regard the power distance, is there a need for a strong hierarchy and large influence of power distance or is it better to work more informal? The amount of power can never be entirely equal and the way the power is shared differs between cultures with a tradition of high power distance and cultures with low power distance (Shore & Cross 2005:5).

The French prefers a strong hierarchy and are trying to avoid uncertainty, they like clear and precise orders, everyone knows what to do and the decisions are made in a clear chain of command. In the other end of the spectre are the Americans who prefer a low power distance where the individuals are freer to take initiative, something that is regarded as a positive feature. Americans are also willing to accept a higher risk in order to achieve a higher goal (Lindell & Arvonen 1996:4; Milosevic 2002:5; Muriithi & Crawford 2003:4). Another issue is how anxious the culture is to avoid uncertainty, to which extent a person feels threatened by unknown situations, and to what extent that person prefers order and a fixed structure (Shore & Cross 2005:5).

There is also a difference in cultural thinking when it comes to the variables of individualism versus collectivism. Where the former features a society where people look after themselves to higher degree compared to societies where group belonging is very important whether it is of the family or part of something more extensive (Lindell & Arvonen 1996:4; Shore & Cross 2005:5).

When organising the multi-cultural team it is worthwhile to ponder over the geographical aspects. Should the team be collocated or not? Is it at all possible to physically work together? If the team is scattered, how strong should the supervision be? Decentralisation brings the benefit of an increase in the amount of initiatives to be taken and there is also some autonomy, which can be a good thing or a bad thing depending on the situation. Although integration and coordination is lost, this is easier to manage with a centralised organisation (Shore & Cross 2005:8).

Learning a culture

With so many variations in ways to behave and react it is clear that a Project Manager working in multi-cultural environment needs guidance. The way we learn a culture's secret code is a lifelong process, a process that starts in early childhood, and continues through education and life experience.

Since the process is so extensive it is very difficult to learn another cultures' whole set of rules (Milosevic 2002:6-7). What most people can hope to achieve is a deeper knowledge and understanding in a few different cultures, hopefully enough to be able to work without offending anyone. The easiest and best way of learning to understand a new culture is through relationships and interactions with people from various cultures. Project Managers that are orientated towards relationships often have a natural ability to increase their knowledge in foreign cultures just by socialising with people or staying in the particular country (Mäkilouko 2004:12).

Project Managers and team members with little exposure to foreign cultures generally show a poorer result when working in multi-cultural environment than their peers with more international experience (Màkilouko 2004:12).

How to avoid and manage culture-related problems

The first step in avoiding culture clashes is to recognise that there are in fact differences. The second step is to find a way to work with and around these differences in order to create harmony. Without harmony in the group it is very difficult to successfully reach the deliverables of the project. The development towards harmony can take various paths; it can either be a deliberate process to reach harmony or a more emergent approach (Milosevic 2002:8).

Strategies to manage a cross-cultural project

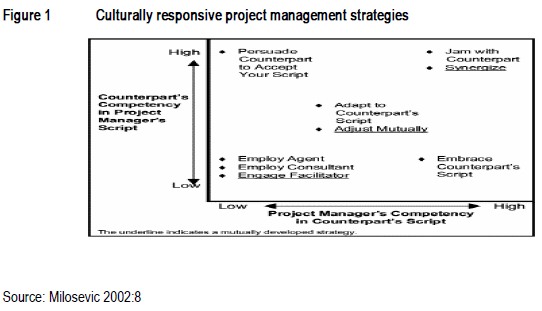

In the literature there has developed various ways of handling these cultural problems when managing a project. Especially the nine strategies grouped according to the Project Manager's knowledge in the counterpart's culture script offer some good options on how to deal with a cross-cultural project.

The strategies are divided into three subcategories depending if the Project Manager carries low, moderate or high competence in the counterpart way of behaving. It also depends on the level of competence the counterpart has in the Project Manager's script.

· Low competence

For a Project Manager with low competence there are four suggested strategies to deal with the problem.

1. Employ an agent

The first strategy is to employ an agent. An agent deals directly with the counterpart on behalf of the Project Manager and his or her organisation. How effective this strategy may be highly depends upon the skills of the agent.

The benefit is that both sides can deal with a person who is familiar with their cultural script; this can make for a smooth cooperation, however if the agent is not very good there is a risk that the agent will cause further misunderstandings.

2. Employ a consultant

If the Project Manager does not want to go as far as hiring an agent, then the second strategy is to employ a consultant. The task of the consultant is to provide information and to make recommendations. This is more appealing to Project Managers since they keep more autonomy and the consultant may only work for one side. This is excellent for an experienced Project Manager who requires some information when working in a foreign environment.

3. Engage a facilitator

In the USA it is now common practise to use the third strategy, to engage a facilitator. A facilitator is a third party who is experienced in the particular field of the project; he or she may step in and create a process for project management interaction. The best facilitator is one who can step in early, to be there from the start and to harmonise the different parties' cultural scripts. Most often a facilitator is brought into the proceedings when problems have already emerged.

4. Persuade the counterpart to follow your own script

The fourth strategy for a Project Manager with low competence in the counterpart's script is to convince the counterpart to follow the Project Manager's own script. This solution may seem very appealing but requires that the counterpart holds a high competence in the Project Manager's script. There are different ways of making this strategy happen, the best way is to verbally persuade the counterpart, and the other way is to push your script and hope or assume that the counterpart will accept this. The latter approach will often create an irritated situation.

· Moderate competence

For the Project Manager with a moderate competence in the counterpart's script there are other strategies.

1. Adapt to the counterpart's script

One strategy is to adapt to the counterpart's script. What the Project Manager does is to alter his or her own script in order to better fit with the counterpart. The difficulty with this approach is to know which elements of the script to modify, leave out or add. Usually the counterpart does not expect the Project Manager to behave exactly as would be expected from their viewpoint. The Project Manager must know which things to observe, to know what part of the script is acceptable to neglect and finally which part would make a good impression to comply with.

2. Adjust mutually

A further development is the strategy to adjust mutually. A mutually adjustment may occur deliberately or as an emergent strategy. This strategy requires great tact and respect for each other's cultures and a great deal of patience. This is an excellent method if the aim is to work together over a longer period of time.

· High competence

Then there is the lucky Project Manager that has reached a high level of competence in the counterpart's script.

1. Embrace the counterpart's script

For this Project Manager one option may be to embrace the counterpart's script. To have this option it is almost always requires many years of exposure to that certain culture and for the majority this is not an option.

2. Synergise

The more viable option is to synergise. When both the Project Manager and the counterpart carry a great deal of experience they can decide to stay within or break the boundaries of their respectively scripts in order to create the necessary solutions in order to make the project work. This strategy differs from the strategy concerning mutual adjustments in the way that the scripts used may be transformed into something completely different, even a third culture's script may be brought in.

3. Jam with the counterpart

The last strategy is to jam with the counterpart, it is easy to draw the similarities from the world of jazz, where there is a conventional theme from which the musicians or in this case the Project Manager and its counterpart improvise without any agreement, making up the script as they go. This requires both parties to have knowledge and insight in each other scripts in order to predict responses and to make decisions without jeopardizing the cooperation (Milosevic 2002:9-17).

Of course these strategies are not fixed; the Project Manager has the freedom to choose and to adapt the strategies to his or her certain circumstances. The Project Manager also has the flexibility to combine different strategies.

The Project Manager must recognise the suitable strategy; some of the variables are of course the time and cost issues as well as the competence in the counterpart's script within the team. The Project Manager must realise his or her own limitations. Only a highly skilled Project Manager may have the ability to use all strategies, it is better to know your limitations and hire help to avoid set backs later (Milosevic 2002:18).

Improvement

A Project Manager can always improve his or her performance as well as knowledge in the counterpart's script along with recognising different situations and how to handle them. It seems that multi-cultural training as well as exposure to many different cultures can be very beneficial in order to work through cultural differences (Black & Mendenhall 1990:118-119,130; Heldman 2004:420; Milosevic 2002:18).

A common saying about Project Managers is that they require knowledge "a mile wide and an inch deep" (Heldman 2004:11), that is also true for Project Managers' knowledge in the multi-cultural field, they need to have an open mind, great communication skills and the ability to quickly identify and use local customs. The Project Manager needs to be curious and have a will to learn, in order to do that he or she needs to be very patient and not afraid to enter into a debate in order to harmonise the different cultures. It is too much to ask that the Project Manager is an expert in these fields, but an exposure is required (Ramaprasad & Prakash 2003:8).

Leadership styles

In a recent Finnish study three different leadership styles were found.

· Ethnocentrism

A majority of the 47 Project Managers studied showed a tendency towards an ethnocentric attitude. This means that the Project Manager is indicating a slightly cultural blindness and favouritism towards his or her own culture, and in some cases, for a few other cultures similar to the Project Managers' own culture.

· Cultural synergy

A minority of the leaders in the study were using a leadership style that can be characterised as striving for cultural synergy. These leaders actively tried to build personal relationships with the members of the team. They also exhibit cultural empathy in a larger extent than the others and they had the willingness to learn and to understand other cultures. The interactions in this team were often more informal and used direct interaction as the main mean of communication.

· Polycentrism

The third leadership style found in the study was a style that is the opposite of the ethnocentric approach, the polycentric approach. The Project Manager is allowing the team members to use their old way of working. These leaders claimed they had the capability of bringing the team together despite different working methods. The Project Managers claimed to be aware of differences in the different cultures and were confident enough to translate them for the team members and by doing so enabled the team to function. The polycentric leaders has to a greater extent combined this thinking with selecting the team members, organising and planning the team beforehand (Mäkilouko 2004:7-10).

Most projects will benefit from reducing the ethnocentric thinking in order to fully benefit from the cultural diversity within the team. Polycentrism is very focused on avoiding and being proactive instead of react to problems when they have already arisen. The synergetic thinking is based on forming personal network as a base for efficient communication. The findings suggest that if the knowledge about other cultures exists then the polycentric approach is very successful, however without the proper knowledge it is very hard to be proactive (Màkilouko 2004:12-13).

COMPARISON BETWEEN AFRICA AND SCANDINAVIA

Since most research concerning project management has been conducted in a western environment it is not surprising to find that most theories in this field are based on Western practice. It is easy to believe that these theories fit everywhere, which may not be the case. The theories have to be adapted to the practical circumstances in each situation in order to be useful.

This becomes evident in the developing countries in Africa where many projects are being initiated by western organisations. This creates conflicts in the way of thinking, often it is the western way of thinking being enforced even though it may not be the most efficient in the particular environment (Diallo & Thuillier 2005:3; Muriithi & Crawford 2003:2). However, there are also differences among the western cultures that have to be respected.

African style

Africa is a large continent and it is impossible to here cover the numerous variations within the different cultures. However it is possible to draw some very general conclusions (Muriithi & Crawford 2003:2,5).

In Africa the social conditions are, in many places, based on strong family ties. There is a strong allegiance to the family or ethnic group; therefore the individuals cannot be expected to be as committed to the project as to the family. The individual is not considered to be successful unless his or her entire family leads a good life. There is a dilemma in this when the organisation where the individual works demands him or her to treat the community in a neutral way. The Project Manager needs to find ways to ensure that the team members are able to fulfil their social obligations; otherwise the team members will look to this before the project (Diallo & Thuillier 2005:18; Muriithi & Crawford 2003:5,9).

Research has shown that there is a strong tradition in many African cultures to have a high power distance and try more than average to avoid uncertainty. Management in Africa often tends to be very inward orientated and keen on controlling everything, therefore it may sometimes be difficult to keep project resources since these have a tendency to be relocated ever so often. The Project Manager must show great skills for politics and special care must be taken to the procurement of both human resources and other resources.

Many African managers have proved themselves to be concerned and committed to reach a high productivity; they especially seem to be very entrepreneurial.

One way to prevail over the problems with the power distance and the deference for authority figures is to build informal networks (Muriithi & Crawford 2003:4,6,8-10).

Scandinavian style

The Scandinavian countries are relatively homogenous but there exists cultural differences within the region.

Scandinavian managers have a relatively high degree of intellectual autonomy which often reflects in the will to cooperate instead of competing. They also prefer structure and organisation but maintain openness for changes and are willing to incorporate new ideas. Scandinavian managers are keen to analyse the problem very thoroughly, even though some research shows an eagerness to quickly try to organise the team and start the project (Shore & Cross 2005:4). Scandinavians are orientated towards individualism; business life is predictable and strives towards results (Trixier 1996:4,7). It is found that many Project Managers in Scandinavian countries rate the importance of their team members higher than the task itself. It is common to build a team spirit consisting of an effective and efficient communication, as well as an open dialogue. Many decisions are driven by obtaining consensus within the team (Lindell & Arvonen 1996:3,7; Mäkilouko 2004:5-6; Trixier 1996:11).

There is tendency to have a very open and informal team structure, it may not always be clear for an outsider which team member got which role. This can often create confusion for someone working in the team not used to that culture; therefore in those cases it may be important to clarify the roles in a formal way. One outcome of this is that work is frequently divided or delegated and the decision-making is often flexible, the structure of the management team is often created as a matrix with more than one person to report to.

However, it is stressed that it is important to maintain good relationships within the team and there are rarely open conflicts. Whichever the way communication is carried out, it can for a foreigner seem very harsh since it is very direct and straight forward without any attempt of softening it. Scandinavian people may also appear very reserved (Màkilouko 2004:6,11; Trixier 1996:4-5,10,14).

The main features of the Scandinavian societies are that they are highly educated and informal; this is reflected in the way teams are organised and the fact that titles are rarely used (Trixier 1996:6,8).

CLOSURE

In the world of project management and how to effectively manage a cross-cultural project there are many things to take into consideration.

In order to fully understand the cultural differences, the Project Manager needs a deep understanding in the different cultures influencing the project. The best approach to understand a culture is to experience it, something not so many people have the luxury to do. Therefore it is vital to the project that the Project Manager is open minded and makes use of one, or a combination of the different strategies that exists. The decision of what strategy to choose depends on how experienced the Project Manager is. The strategies available stretch from using an agent to being able to jam freely with the counterpart; making up rules of their own as the project advances.

Managing a cross-cultural project will add extra variables to the way the project has to be managed. For example there may be different calendars to deal with and each culture has its own set of special days that will have to be respected. Communication is one of the most important skills for a Project Manager and working multi-culturally, this skill will really be put to the test. Not only due to different languages, but also how to communicate; body language and various social codes have to be interpreted. The easiest way for the Project Manager to handle this is to try to clarify as much as possible. The Project Manager should try to avoid offending anyone, better to ask one too many times than taking something for granted and causing embarrassment.

Organising the project team also takes some planning since people from different cultures bring in different perspectives of how to work as a team. One thing to consider is hierarchy; it is necessary to have a clearly defined leader.

In Africa there is often a high power distance whereas in the Scandinavian countries there tend to be less distance and more open discussion, decisions are often reached in consensus. In Africa, family is the main concern for many team members and the meaning of the community is highly stressed, this is not so much the case in Scandinavia. In both areas it is beneficial to have well-structured networks, informal as well as formal.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANDILA M. 2005. Kroppen avslöjar dig - du sjàlv àr budskapet. [Internet: http://www.kolumbus.fi/andila/kropp.html; downloaded on 2005-04-22. [ Links ]]

BLACK SJ & MENDENHALL M. 1990. Cross-cultural training effectiveness: a review and a theoretical framework for future research. Academy of Management Review, 15 (1):113-136, January. [ Links ]

BROWN M. 2003. How to use visual aids more effectively in your next presentation. [Internet: http://www.media-associates.co.nzf-visual-aids-presentation.html; downloaded on 2005-04-27. [ Links ]]

CAMPBELL J. 2004. Chinese FAQ. [Internet: http://www.glossika.com/en/dict/faq.php; downloaded on 2005-04-26. [ Links ]]

DIALLO A & THUILLIER D. 2005. The success of international development projects, trust and communication: an African perspective. International Journal of Project Management, 23(3):237-252, April. [ Links ]

FOGEL IM. 1998. International or cross-cultural projects. AACEInternational Transactions. Morgantown pp. 1314 [ Links ]

HELDMAN K. 2004. Project Management Professional. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Sybex. [ Links ]

HOECKLIN L. 1995. Managing cultural differences - strategies for competitive advantages. Singapore: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

LINDELL M & ARVONEN J. 1996. The Nordic management style in a European context. International Studies of Management and Organization, 26(3): 73-91, Fall. [ Links ]

MAKILOUKO M. 2004. Coping with multi-cultural projects: the leadership styles of Finnish Project Managers. International Journal of Project Management, 22(5):387-396, July. [ Links ]

MILOSEVIC DZ. 2002. Selecting a culturally responsive project management strategy. Technovtion, 22(8): 493508, August. [ Links ]

MURIITHI N & CRAWFORD L. 2003. Approaches to project management in Africa: implications for international development projects. International Journal of Project Management, 21(5): 309-319, July. [ Links ]

RAMAPRASAD A & PRAKASH AN. 2003. Emergent project management: How foreign managers can leverage local knowledge. International Journal of Project Management, 21(3):199-208, April. [ Links ]

SIMMONS GF. 2002. Patchwork: the diversities of Europeans and their business impact. In Simmons GF (ed). Euro Diversity - A business guide to managing differences. Woburn, Massachusetts, USA: Elsevier Science, pp. 1-34. [ Links ]

SHORE B & CROSS BJ. 2005. Exploring the role of national culture in the management of large-scale international science projects. International Journal of Project Management, 23(1):55-64, January. [ Links ]

TRIXIER M. 1996. Cultural adjustments required by expatriate managers working in the Nordic countries. International Journal of Manpower, 17(6/7):19-38. [ Links ]