Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Journal of Contemporary Management

versão On-line ISSN 1815-7440

JCMAN vol.1 no.1 Meyerton 2004

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Information Technology: management issues in the due diligence and contracting phase of outsourcing contracts

D CoetzeeI; N LessingII

ISiemens Ltd

IIRAU

ABSTRACT

This article concerns the investigation of management issues in the due diligence and contracting phase within information technology outsourcing contracts. The information technology outsourcing life cycle is used as the flow structure for the investigation. The associated user expectations that occur in the due diligence and contracting phase of the information technology outsourcing life cycle are identified. Following the identification of the management and user expectation issues in the due diligence and contracting phase of the outsource life cycle, the "Coetzee solution framework is used to ensure that the identified management problems are addressed in a structured approach.

Key phrases: information technology, information technology outsourcing, due diligence and contracting phase, management issues

BACKGROUND TO MANAGEMENT ISSUES IN THE DUE DILIGENCE AND CONTRACTING PHASE

There are many failures and successes when it comes to information technology outsourcing (ITO), and the failures can often be tracked to the manner in which an ITO was approached and the immediate management of problems that arise during the ITO lifecycle. The Outsourcing Institute indicates in their research (Casale 2001:6), that the "key concerns with buyers and vendors - that governance issues are usually top of mind".

The institute also states that "a lot of people used to think that once you outsourced, the tough part was over, when in fact, just the opposite is true. Now, people are giving a lot of thought to managing the relationship over time". The key is that a proper foundation be constructed during the decision to outsource and the subsequent search and appointment of a suitable vendor. This foundation is required in order to ensure that proper governance can be implemented during the contract life cycle.

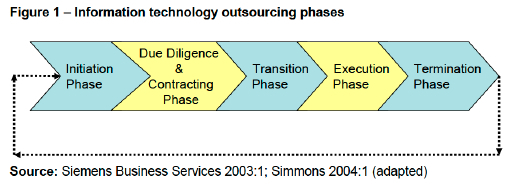

There are essentially five main phases in an information technology (IT) outsource contract life cycle as is described in Figure 1. [Each of these phases was described in the context of the ITO life cycle phases in the article of Coetzee & Lessing, pp 1-15 of this issue and is not repeated here.] This article will only focus on the due diligence and contracting phase of ITOs to describe the management issues, user perception problems and the relevant solutions that are available to address the management and user perception issues.

The due diligence and contracting phase was introduced as follows:- Once the organisation has identified the vendor or vendors that they wish to continue working with, they open up their environment to the vendor to investigate the environment thoroughly in order to come up with the best and final offer (BAFO). Thereafter the organisation evaluates the BAFOs and decides on the final vendor. Contract negotiation is entered into to finalise the outsourcing agreement.

In this article the due diligence and contracting phase is discussed in the context of the problems that typically arise as time progresses. This is not meant to be an exhaustive discussion on the issues, but merely a short overview of some of the main problems that do occur.

TYPICAL PROBLEMS WITHIN THE DUE DILIGENCE AND CONTRACTING PHASE

The initiation phase is the foundation on which the ITO is built, but most vendors will insist on doing a full due diligence in order to verify the details that were supplied during the RFP. Harris (2002:18,32) has found that one of the weaknesses of outsourcing is that the vendor does not always carefully confirm the customer's expectation and that the vendor does not make certain that they understand exactly what all the customer stakeholders are expecting. This is extremely important and the organisation and vendor should plan a careful due diligence process and agree this prior to due diligence starting.

Many organisations require the vendor to drive the due diligence, but this does cause problems later on, as the vendor very often focuses on those elements which they deem interesting or have core competence in and often forget to take a holistic view of the environment especially in terms of process and business objectives. Harris (2002:31) says that organisations do not spend sufficient time in structuring the review, or due diligence, and also on the management of the vendor evaluation, RFP development and contract review.

The organisation should decide as to whether they wish to take a multi-vendor versus a single-vendor approach on the due diligence. Having more than one vendor performing a due diligence at a time can place significant strain on the operating environment and can potentially disrupt service, which in turn influences user perception regarding the ITO.

Throughout all phases communication becomes more of an issue in order to manage expectations, perceptions and to combat staff uncertainty. Communication is a major contributor to buy-in, unless this is done effectively, buy-in is not obtained at all levels. This can result in withholding of information by staff members that feel that their positions are potentially at stake.

The GartnerGroup (1999:4) has found that organisations must evaluate and reestablish the levels of service required by their business prior to outsourcing, thereby developing reasonable and attainable service expectations for the vendor. By involving the end users in the process and explaining the goals (i.e., to manage costs), the organisation will be able to institute new levels of service that deliver the desired business results.

Best practice requires the organisation to: set user expectations for the service based on clear simple metrics and projections (consistency reduces the degree of mistrust users feel about technology); encourage direct customer involvement - flattening the service organisation by including the customer in the service chain increases trust by reinforcing a sense of equality and empowerment; and create a threshold that marks the boundary of the support infrastructure. The vendor often uses the due diligence phase as a mechanism to build relationships. This in turn increases user expectation and the expectation curve grows steadily in terms of expectation of services, scope and enhanced delivery.

It is essential at this stage that the exact service scope is known and user expectation is set around this. Limiting scope is one of the biggest problems that faces both the organisation and the vendor as the due diligence inevitably raises facets that were not considered before, often because the organisation did not spend enough time understanding their own environment in the initiation phase. Vague statements around scope result in major disputes once the operations start and can also affect the cost significantly in terms of the vendor claiming that elements are out of scope while the organisation's interpretation is that the element is within scope. This disrupts operations until such time as the dispute is cleared which in turn start affecting user perception re the success of the ITO.

Gartner research (GartnerGroup 1999:17) show that it is key that organisations perform a detailed benchmark analysis of IT costs and competencies before soliciting the services of an outsource vendor. Harris (2002:32) also points out that a key failing of a vendor is to very carefully confirm the customer's expectation and make certain that all stakeholder expectations is understood and formalised.

Another major shortcoming in ITO is the amount of time spent on legal negotiations. The vendor would typically have a standard contract they suggest to the organisation, or the organisation gets an example contract from a consulting house which is then used as a basis for negotiation. Gartner (GartnerGroup 1999a:13) has found that contracts have become disjointed mixes of standard terms for outsourced operations, boiler-plate language about projects, and lists of vague promises for future services. This is an unacceptable situation. These deals are impossible for vendor or the organisation to manage. Vendors are losing money on them. Organisations are losing credibility with the business because of budget overruns, poor service and broken promises.

Working out the exact details of the costing mechanisms, service definitions, service level agreements (SLAs), scope, business and technical objectives, asset lists, staff affected, security considerations, exclusions and many other elements are the essence of understanding of operations and responsibilities later during the contract. It cannot be emphasised enough that this must be worked through and agreed in detail, then communicated to the organisation so as to set accurate expectations.

Hand-in-hand with the detailed contract scope must be the definitions of the governance structures that will be used to govern the operations of the contract and the interaction between the organisation and the vendor. Looking at existing ITOs throughout the world, it is very often poor governance that leads to disputes and relationship breakdowns. Governance has to be solid from contract inception through the contract life cycle to termination. Without proper governance, verbal agreements and confusion reigns which cannot be healthy for a long-term relationship. Research by the GartnerGroup (1999:2) has shown that one of the most common reasons for the success or failure of outsourcing deals lies in an organisation's ability to fully appreciate, plan for and manage its role in the arrangement. Organisations must establish the skills, processes, resources and tools to effectively manage their outsourcing arrangements for the duration of the agreement.

The Outsourcing Institute (Casale 2001:6) has found that vendors and customers alike should focus more of their effort around "paying attention to the contract and contract governance". They further indicate that it means having the day-to-day relationship in a governance model that is described in writing, and that has to include an executive team relationship, where top managers meet, perhaps on a quarterly basis, and talk about business and technical issues. They indicate that this is a major source of breakdown in relationships between the vendor and their customers and often lead to chaotic effects on the business of the customer and the vendor.

Another major failing during the due diligence and contracting phase is that the existing organisation processes surrounding IT are not investigated in detail. Research (Harris 2002:31) on this issue indicate that organisations and vendors do not spend enough time understanding the applications, protocols, change management policies and procedures within the organisation or the vendor environment. The way the affected area within the organisation operates is thus not understood. The vendor will during transition phase define their own processes which causes a major breakdown in operations and communication between the organisation and the vendor.

It is further critical that the vendor physically verifies the information supplied by the organisation and that the agreed correlation is used as a baseline. As an example it is not acceptable that an organisation provides an asset register, which is merely an extract from their financial system, and that this is used as the basis of the actual physical assets, as very often these lists do not match and are not updated to the actual equipment that is deployed due to various reasons, such as changes of configurations, equipment being dumped and not repaired, and many other.

It is important during the contracting phase that the exact mechanism and cost equation for future termination of the contract is discussed, agreed and documented in detail. This is often left in the hands of the vendor which results in major financial and service implications for the organisation at the end, or during the termination of the contract at any point. GartnerGroup (1999a:16) also indicates that part of the contract strategy should include the termination mechanism which is often neglected.

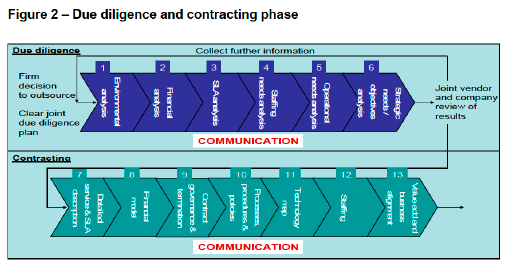

At this stage the contract is typically concluded and the vendor enters into transition mode. As per the Gartner user expectation curve, refer to figure 2 (due diligence and contracting phase), expectations at this stage are reaching its highest level and users are expecting dramatic improvements in service delivery and scope of services. The details have probably not been effectively communicated to the entire organisation, and as such, the agreed services and scope within the contract is not understood by all.

The due diligence and contracting phase is critical in terms of establishing the exact scope and baseline according to which services will be delivered and should match closely with the initial objectives, baselines and understanding that the organisation would have set during the initiation phase. If there are radical differences, then caution should be taken by the organisation to re-look at their original investigations and ensure that ITO is still the best option for the organisation.

THE COETZEE SOLUTION FRAMEWORK FOR THE DUE DILIGENCE AND CONTRACTING PHASE

On completion of the initiation phase, and a positive decision by the board of the organisation to continue with the ITO contract, the due diligence and contracting phase is entered into. This phase is part of building a proper foundation for the future ITO relationship and should be given all attention possible. Expectations are set during this phase as the vendor will be interacting directly with all level of users throughout the organisation in order to gain as much insight into the environment as possible and to cross-check the RFP detail that was given. The contract structure will result from the vendor findings combined with the initiation phase data that was investigated. If done properly, a solid contract reflecting current business needs as well as future strategic requirements can be formulated and used as the basis for a constructive and mutually beneficial partnership between the vendor and the organisation. The framework steps for this phase are depicted in figure 2.

It is essentially a thirteen-step model as depicted in figure 2 to cover all the issues that were highlighted for this phase. This phase should be entered with a clear plan as to how the vendor will be able to complete the due diligence phase (steps 1 to 6), in cooperation with all staff within the organisation. The model is as follows:

Step 1: Environmental analysis

This is exactly the same exercise that the organisation should have gone through, in detail, during the initiation phase. The step is in place for the vendor to cross-check and to conduct a complete audit on the organisation's IT environment in terms of staffing, hardware, software, networks, capacity usage, performance, data volumes, facilities, locations and configuration complexity with the view to understanding the full environment envisaged for outsourcing in micro detail. Full inventories, asset registers and application maps should be defined in detail with all interdependencies mapped. This should map back to the organisation findings, but allow the vendor to become familiar with the environment to be taken over. It is both the responsibility of the vendor and the organisation to ensure that this is done properly. The vendor often has speciality fields which will cause their engineers to focus on the things they are comfortable with. This must be avoided as the environment is mostly more complex than the speciality fields of the vendor.

Step 2: Financial analysis

This step is critical whether the organisation has decided to disclose the full actual cost environment or not. If the organisation does not wish to open their books (financial system entries and budgets) to the vendor, then the onus lies with the organisation to check the vendor proposal against their initial financial analysis to ensure that the vendor has covered all elements. If not, this will cause severe relationship issues later as the vendor will battle to maintain profitability and as such fail in the ITO services. If the organisation decides to open its books, then the vendor should be guided through a full financial audit to identify and account for ALL costs surrounding the infrastructure as identified under the first step. There are often hidden costs in the IT environment with procurement taking place from various areas throughout the organisation and not necessarily being accounted for as IT. The vendor needs to understand all these elements, including all procurement channels and third party contracts, services and products. The vendor further needs to understand the financial obligations in terms of encumbered assets, depreciation values, staff benefits and contingencies.

Step 3: SLA analysis

Once the environment and finances around the environment is understood, it becomes fairly easy to map the current service levels associated with the relevant costs. Although some vendors have pre-defined SLA's between business and IT, this analysis often shows the discrepancy between what is thought is being done versus the actual situation. It must be noted that it is critical that the organisation does not at this point define what their desired SLAs should be, but that reality is defined and mapped in terms of actual and practical services being delivered.

Step 4: Staffing needs analysis

The staff required to uphold to SLAs as defined in step 3 must be identified and their roles and activities evaluated in relation to the envisaged ITO environment. The staff's full benefit structures and incentives need to be understood as well. This is a sensitive time for the staff as they might have become aware that the organisation is considering an ITO. Communication by the organisation management regarding intent needs to be transparent and the business reasons needs to be stated. The vendor and the organisation management should communicate openly with the affected staff at this point to ensure that the fears are managed and that unnecessary blocking of activities does not occur by the staff.

Step 5: Operational needs analysis

The environment, finances, SLAs and staffing needs are now understood by the vendor from the previous steps. Now it becomes an imperative to understand what the organisation would like to see in terms of operational excellence. This is a step that few vendors or organisations fully appreciate. Absolute clear understanding of these expectations goes a long way to ensure that the vendor aligns with the service expectations of the organisation, or jointly agrees what these expectations should be. All normal operational elements must be re-looked at in terms of what the organisation would practically expect from the vendor in terms of improvements. These expectations should be stipulated in exact detail and agreed between the two parties. The staffing requirements need to be reinvestigated as well in terms of what would realistically be required to fulfil the new expectations. It is once again very important to communicate the expectations, as explained to the vendor, across the organisation in order to ensure that all staff knows what the point of departure is from which the vendor will operate.

Step 6: Strategic needs / objectives analysis

This step defines the strategic intent of the ITO and should not be neglected under any circumstances. This step should be used to map out the strategic goals of the organisation and then to investigate what is required by IT to support the achievement of these goals. Once this is defined, the ITOs long term expectations, intent and objectives for the duration of the envisaged contract, should be defined. A gap analysis of how the current IT environment performs against these strategic goals should also be detailed in order to position the real situation against the ideal situation. This must be done to position expectations for future management members to understand the history, frame of reference and context of the possible ITO in future years, but also as a yardstick of how the ITO has complied over time to the initial intent. It is imperative that the vendor understands this as often an ITO is viewed as an operational element only, while it actually supports the organisation's ability to be competitive in the current and future business environments it wishes to operate within.

Once steps 1 to 6, as per figure 2, are completed by the vendor, the organisation and vendor should compare findings to ensure a consistent image of the ITO environment is understood. If there are any gaps, the vendor and the organisation should jointly investigate these by going back to the relevant step where the gap exists. Both parties should now have a very clear understanding of the environment and should be able to enter the contract negotiation with clear expectations and objectives.

The contract negotiations should go through the following steps, as indicated in figure 2, to ensure that all elements are covered. It is critical that enough time be spent on contract negotiations as possible to ensure that a complete and fair contract is formulated for both parties reflecting the organisation operational requirements and strategic intent. The organisation should take control of contract development and structure agreements to meet their long-term needs. The organisation must ensure their outsourcing agreements are built for continuous change (GartnerGroup 1999a:14).

Step 7: Detailed SLA and service description

This step is taking the output from steps 1, 3 and 5 in figure 2 and formalising it as the official service description with the associated detailed SLA's for each service area. Many vendors have standard service and SLA descriptions. This can only be used if the mapping to the actual SLA and service environment is understood and agreed by all. It is critical however to ensure that a common language is used and understood by both the vendor and the organisation in terms of some of these standard service clauses as interpretation and definition can differ widely from what the organisation normally uses. Both parties have to fully agree that the defined SLA and service descriptions cover all aspects of the ITO requirements. The metrics by which the SLAs will be measured and cross-checked must also be defined and agreed in detail, including the format in which it is to be reviewed.

Step 8: Financial model

The financial model is one of the critical elements in the future governance of the relationship. The organisation should have decided during the initiation phase what the model for billing and financial management should be. This step is often not given enough attention and the vendor will propose their own in the event that a model is not available. Due to the nature of financial discussions this can cause major problems in the relationship as both parties have to be clear on the method of billing and how additional service costs will be determined and billed. The transparency factor required by the organisation should also be agreed by both parties and the format and control that are associated with this. There are many models available which range from user-based billing, service-based billing, business-outcome based billing or risk and reward billing models (GartnerGroup 1999a:6). The billing model should be carefully thought through by the organisation as the long-term nature of the contract does not necessarily allow for changes in the ITO life. The vendor and organisation should agree the model in detail looking at any future scenario that they can think of. The exact mechanism on increases, decreases and base line cost changes should be agreed and documented at this stage. It is important to state the exact objective of the billing model and the context in which the model was decided to ensure that future management, in the event of changes, understand why the particular model was chosen. Clear reporting and cross-check formats should be agreed at this stage as well.

Step 9: Contract governance and termination

In many ITOs this step is given minimal attention although this is the topic which causes major relationship issues a year or two into the contract. Many organisations and vendors believe that governance is a natural fact of delivery and is finalised during the operational phases, which is however rarely the case. It is critical that both parties negotiate the governance mechanisms upfront in order to avoid confusion during transition. The typical governance mechanisms should cover the strategy (contract and business alignment), the tactical level and the day-to-day operational level. Predefined meetings with associated mandates and agendas should be agreed and expected outcomes should be documented. This will ensure that formal governance is adopted from the start of the ITO through to the end. Changes to the governance structure should only be made at the executive levels between the vendor and the organisation.

Proper change control procedures and decision making bodies should be established to decide on all changes, the implementation thereof and the impacts it will have on all facets of the contract and customer. Another element that has to be given major attention, and which is not always pleasant during contract negotiation, is the exit or termination mechanism and procedure. Both parties have to agree upfront exactly what the cost formula for termination will be, the reasons why termination could occur, and the plan that will be followed for termination.

The question might be asked why this needs to be done up front, the answer is simple that when termination does occur and the ITO has not yet reached the end of its life cycle it is often under unpleasant relationship related circumstances. If the termination procedure is not clearly stipulated and if there is a relationship breakdown, it becomes a major emotional dispute and rational and logical thought does not prevail and both parties revert to the contract. As such both parties should make sure that they spend enough time thinking through and agreeing the termination schedule.

Step 10: Process, procedures and policies

The vendor often suggests that processes and procedures be agreed during transition. This is not acceptable. Both parties should work in detail through their respective sets of procedures and processes that they use to govern their IT environment. A mapping should be done between the two organisations processes and policies to understand any major differences. Modifications should then be agreed and the new/modified procedures and processes should be documented in the contract. This will prevent any misunderstanding of which process or procedure will be followed given any circumstance. Not defining these processes and procedures lead to major chaos during transition as each party will be working from their frame of reference. Any policies to be followed by either party should be clarified and stipulated in detail in the contract as well. These policies typically relate to security, the physical environment, health and safety, asset care, dress code and data security. It must never be assumed that the vendor understands these policies, and as such should be documented in the contract.

Step 11: Technology map

The envisaged technology roadmap should also be defined in the contract. Even though technology changes rapidly, the parties should both agree on the envisaged technology route they intend on taking at the start of the contract for the full contract duration. This will create purpose and ensure that all stakeholders understand the end goals to be achieved by the contract. The key part of the roadmap should include technology standards, architecture, the application strategy, the future vision for IT and the technologies required to realise the vision. As major technology changes occur this roadmap should be adapted during the contract following strict change control. The initial intent is formulated and defined in the roadmap and is as such a critical element for future managers and staff within the organisation to understand the vision of why the ITO was entered into. The vendor and organisation IT staff should agree this roadmap with executive management of both parties. This will insure a common understanding of the purpose of the contract and will as such form part of the foundation on which the operations are delivered.

Step 12: Staffing

This section of the contract focuses on any specialised staff or skill that will be required to support the operations of the contract. The expectations around the number and type of staff to support the operations should be stipulated in the event that the contract is defined around resources. This should however never be the case as the organisation should be buying services from the vendor and not resources. Only specialised skill should be defined in this section. There might be staff that will be transitioned from the organisation to the vendor where the organisation wishes those staff to be employed for a guaranteed period of time. The time frame and conditions under which this guarantee will apply have to be detailed here as well. This practice is becoming obsolete as staff transitions are becoming less frequent or organisations are retrenching or arranging alternative placements for staff as part of the ITO. The content of this section needs to be communicated to the affected IT staff during this process.

Step 13: Value add and business alignment

This is probably the most difficult section of the contract to define, but should not be underestimated as this will form part of the perception (whether defined or not) during the ITO life cycle. If it is not defined, it will be questioned for the duration of the contract and could potentially cause a complete breakdown of the contract. It is the organisation's responsibility to stipulate what value-add is expected from the vendor from all angles, including technology, architecture, strategy and operations. It is the vendor's responsibility to expand on and stipulate the detail of the organisation expectations. The reason for this is that it is normally commodity services that are outsourced, and it is difficult after a number of years to understand why the organisation could not have delivered these services internally as effectively as any third party might be. Provision is also not always made in the contract for changing the scope of the commodity service as the service is being delivered more efficiently after the first few months or years of the contract.

It is imperative that the service definition and the business outcome to be achieved are reviewed periodically during the contract life span. The basic service definition should always remain the common point of reference for the ITO. Business-output-based metrics should always be built into the operational measurement of the contract. Gartner best-practise (GartnerGroup 1999a:7) says that the business case should set the brief for the outsourcing solution, focus on benefit measurement and be continually updated throughout the life of the agreement.

The contract and due diligence phase information need to be communicated, in detail, to the entire organisation, staff and management. The vendor has to do the same for the staff that will be working on the contract. Communication around every element of the contract is critical in order to form a realistic user expectation of what the contract will deliver, the processes and procedures that will be followed and the service levels that will be delivered. Harris (2002:4) says that some of the lessons learnt around communication are to simply identify goals and objectives very clearly, and communicate them explicitly. Constant communication from this point onwards for the duration of the contract is important in order to manage user expectations. A careful communications strategy and plan should be worked out jointly between the vendor and organisation and should be followed religiously.

This phase sets and completes the expectations from both the vendor and organisation in regard to how the relationship will be managed, how the contract will be governed and what services will be delivered within the ITO. The contract will also define the strategic intent and the context in which the ITO was decided on a formal legal basis. The importance of this is that the contract will be the only point of reference that a court of law or an arbitration council will use to evaluate whether the vendor has performed what was contractually requested by the organisation.

Many vendors have pre-defined contract structures, service definitions, processes, procedures and service level metrics in place. If these are used as the basis for this phase then care has to be taken to make sure that the organisation understands precisely what is meant in each of these descriptions and definitions.

Most of the global outsource vendors have got detailed due diligence templates, and procedures for investigating the environment. Although these are best practice, the vendor focuses on those elements in which it has core expertise. As such it is important for the organisation, and an actual obligation, to check that the vendor studies and analyses the environment holistically.

The sequence of the steps referred to in figure 2 is not important as many of these activities can be engaged in parallel.

CLOSURE

The complexity of managing outsourcing transactions is often the reason for dissatisfaction. This dissatisfaction stems from the incorrect initiation of the ITO where not enough investigation was done by the sourcing organisation. This results in incorrect definition of expectations and scope of the project. The vague scope is then translated into a contract around which governance is not clearly thought through or properly implemented. Communication in regard to all facets of the ITO is not always given enough attention leading to confusion, politics and unrealistic expectations.

The due diligence and contracting phase along with the initiation phase is the foundation phases for ITO. During these phases it is critical to establish an in-depth understanding of the strategic intent of the ITO and also the realities of existing ITO target environment combined with a realistic view of what the ideal ITO environment should be. Without this understanding and a contract that is structured to reflect the environment and strategic intent, the ITO is likely to have many problems around relationship, expectations and governance. The value-add of the ITO will most certainly be questioned on a constant basis.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Note: The Gartner research group consist of a number of companies that focus on various areas of the market. Gartner DataQuest is the information technology research unit within the group. The GartnerGroup general conference papers are normally produced on behalf of the entire group of Gartner companies and not in terms of specific authors. Gartner further produces various research reports which are written by specific authors.

CASALE F. 2001. IT outsourcing: the state of the art. The Outsourcing Institute. October. [ Links ]

GARTNERGROUP. 1999. Managing outsourcer relationships. GartnerGroup conference presentation. November. [ Links ]

GARTNERGROUP. 1999a. Making the decision to outsource. GartnerGroup conference presentation. November. [ Links ]

HARRIS M. 2002. Network outsourcing: lessons from state government. Gartner focus report. 3 May. [ Links ]

SIEMENS BUSINESS SERVICES. 2003. Outsource framework. Outsource reference for customers - http://www.siemens.com/index.jsp?sdcp=i1026935z3lo1046283t4u2mcdn1045363s3fp&sd sid=6951080468&. January. [ Links ]

SIMMONS. 2004. The outsourcing life-cycle: 9 stages. http://www.corbettassociates.com/firmbuilder/articles/19/48/945/. [ Links ]