Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.38 n.1 Stellenbosch Mar. 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/38-1-6280

SPECIAL SECTION

Mind the GAP - industry perceptions about postgraduate studies in the discipline of design

H. M. van Zyl

Independent Institute of Education: IIE Vega School, Pretoria, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7159-2766

ABSTRACT

There has been slow uptake and growth in the local postgraduate student numbers in design, especially at the doctoral level. The question must be asked why, especially when looking at the growth of design as a discipline and a widening domain resulting from technological and social development. This study aims to explore industry perceptions about postgraduate studies in design to see if that could be a reason for the slow growth. The study starts with the background of the development of the design discipline, design education, and design research. An analysis of postgraduate graduate numbers over the last decade and current providers provides a context and general landscape. The analysis is followed by a report where the perceptions and attitudes of industry practitioners about postgraduate studies in communication/graphic design were qualitatively explored. The fieldwork comprised in-depth interviews that were conducted with communication designers at various points along their career paths. Three elements were explored: identification of the type of advanced knowledge needs in industry; how design professionals see postgraduate studies, their career paths, and vision for the future; and if postgraduate studies feature in their vision for the future. Some of the participants had previously attempted postgraduate studies and were not successful; their experiences added to the rich data. The research contributes to a better understanding of the reasons for the low postgraduate numbers, and the gap between industry and academia at postgraduate levels is confirmed. The study insights provide the possibilities of increasing postgraduate capacity in design by reducing the gap when designing suitable curricula.

Keywords: communication design, industry perceptions, postgraduate studies

INTRODUCTION

Undergraduate design education in South Africa is experiencing substantial growth characterised by the ongoing development of new courses and curricula that mirror advancements in the design industry, emerging media, evolving market demands, societal shifts, and technological changes. However, this expansion is not mirrored in postgraduate design education in South Africa, where student enrolment remains consistently low. Institutions and universities offering design qualifications face the dual challenge of securing faculty members with suitable advanced qualifications1 and securing local material, case studies, and content for use in education.

This study aims to investigate the relatively low enrolment of postgraduate students in communication design, a comprehensive disciplinary field encompassing graphic design, information design, illustration, multimedia, and digital and motion design. Additionally, the study intersects with emerging design domains such as user interface (UI), interaction, and user experience (UX).

The study begins with a literature review and desktop analysis to offer an overview of design education, with a specific focus on postgraduate student numbers. Subsequently, the research delves into industry perspectives on postgraduate studies, aiming to discern whether these viewpoints contribute to the apparent scarcity of postgraduate students in the field of communication design in South Africa. In order to achieve this objective, semistructured interviews were conducted with selected designers representing various stages in their career paths. The gathered data was thematically analysed to extract insights and patterns.

The overarching purpose of this study is to develop comprehension of the connection or alignment between postgraduate education and the industry. The international and local literature extensively recognises the demand for research and knowledge progression in design (Corazzo, Honner, and Rigley 2019). Despite this recognition, scant information exists regarding the perceptions and awareness of the significance of postgraduate development and design research within the local communication design industry. This study aims to contribute to this knowledge gap that could help develop postgraduate courses and, eventually, student numbers and research capacity.

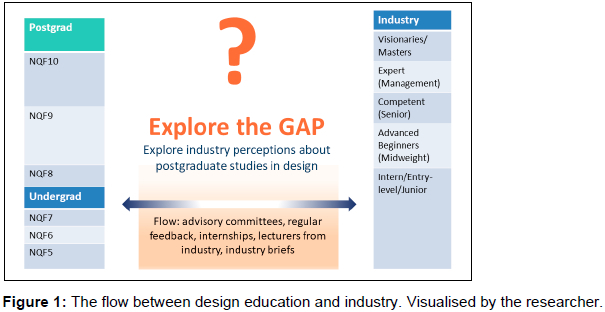

There is a consistent exchange of information and a strong connection and flow between education and the industry at the undergraduate level (Figure 1). This connection is fostered through advisory committees, frequent feedback, internships, guest lectures, and the involvement of part-time lecturers who have industry experience. But is there any alignment beyond that? And how do designers in industry perceive postgraduate studies or designers with postgraduate qualifications? Could industry perspectives provide any information and insights to better understand the low numbers in postgraduate studies in design? These are the questions that drove this article.2

LITERATURE REVIEW

Shifts in design education

Design is an activity as old as humankind. Still, design is a young academic discipline, even more so in South Africa, where we are somewhat behind in developing design as an academic discipline. Design education moved from a craft-based activity taught by a master to an apprentice to being formally taught at a university in the 1920s at the Bauhaus, and has since then become an accepted and mature research and academic discipline taught at bachelor, master's and doctoral levels (Voûte et al. 2020; Meyer and Norman 2020). The first "commercial art" courses in South Africa were introduced in Arts and Crafts schools during the 1950s, and colleges started to offer a National Diploma in Graphic Design in 1966 (Lange and Van Eeden 2016). Twelve public higher education institutes offered design education by the 1980s, mainly at technikons and a few at Afrikaans universities. Design qualifications were often part of a Fine Arts education (Lange and Van Eeden 2016). Since then, the higher education space in South Africa was restructured and went through a stage of mergers in the early 2000s where some universities and technikons were merged, and some technikons became universities of technology (UoT) or part of the new comprehensive universities that offer both diplomas and degrees (Boughey and McKenna 2021). The second major change was the restructuring of the National Qualifications Framework, gazetted in 2014, where the BTech (a fourth year that followed a national diploma) was discontinued (Boughey and McKenna 2021). The impact of these changes on postgraduate design education will be discussed later.

Meyer and Norman (2020) point out that design education should develop and become an academic discipline to achieve a broader skillset and mindset, and should ask how design education should change at all levels, including master's and doctoral levels. As a discipline, design developed over the last 100 years from focusing on function and consumers to focusing on humans, society, humanity, and life - a shift from a manufacturing to a service economy (Singh, Lotz, and Sanders 2018). This shift requires designers to be professionally, socially, and environmentally responsible agents who are supported by research-based decisions (Fraseara 2022). Design educators should adjust to these changes and anticipate future design education demands, the balance between what is certain and what is uncertain and future directed (Singh et al. 2018; Redström 2020).

Corazzo et al. (2019) specifically highlight the necessity for a research culture in communication/graphic design. This research culture is crucial for establishing discovery-oriented approaches that have the potential to generate new knowledge beyond industrial practice. The aim is to transition from an emphasis on aesthetic and intuition-led activities to more meaningful practices and to create pathways for career advancement. This shift is in response to the broader transformation from a manufacturing and function-focused economy to a service-oriented one, with a heightened focus on humans, society, humanity, and life (Singh et al. 2018).

One proposed strategy to foster a research culture is to develop a clearer articulation of the "centrality of research" in both education and practice, as advocated by Corazzo et al. (2019, 20). This need for a research culture underscores the importance of postgraduate studies where individuals can develop essential research skills.

Postgraduate education in design

International debates persist regarding the ideal terminal qualification for designers. One point of contention is which form of qualification would be most suitable: a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) or MDes (as seen in the USA), or master's degrees aligned with work experience (similar to an MBA) (Sarrico 2022; Griffin 2016). The terminal qualification in South Africa is a degree or diploma (Van Zyl and Carstens 2023). Higher education qualifications in South Africa are structured as follows:

• Undergraduate: NQF5 - higher certificates; NQF6 - diplomas; and NQF7 - degrees and advanced diplomas.

• Postgraduate: NQF8 - bachelors, honours, postgraduate diplomas, and four-year bachelors; NQF9 - master's or professional master's; and NQF10 doctorates or professional doctorates (CHE 2014; 2022).

Each NQF level is supported by a Framework for Qualification Standards in Higher Education (CHE 2014), with each level set to achieve learning outcomes and deliver on level descriptors and aligned graduate attributes (CHE 2014). The doctorate degrees, at the highest level, aim to develop the graduate attributes embodied in "doctorateness" with suitable knowledge and skills (CHE 2022). Doctoral graduates should also be able to communicate research findings effectively to expert and non-expert audiences (CHE 2022, 87):

"[A doctorate] requires an original contribution to knowledge, which may - and, in the case of a Professional degree, should - contribute to the advancement of professional practice, and that can be disseminated to relevant parties in order to contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the relevant field of study, discipline, profession, or creative domain."

The nature of the purpose of the doctorate in design is now becoming more established as the discipline matures, but Voûte et al. (2019) question doctoral education in design. Doctoral degrees are seen as a way to boost national competitiveness (Sarrico 2022). However, there are limitations to the potential to absorb doctoral graduates back into academia or for doctoral graduates to find a position in the workplace (Sarrico 2022). One way of overcoming this challenge is the development of collaborative or professional doctorates that are seen to be more applied, or in design-space or practice-led3 doctorates where design activity becomes part of the research process (Sarrico 2022; Meyer and Norman 2019; Goff and Getenet 2017).

An alignment between universities and industry could increase mobility for doctoral graduates. We currently have virtually no data on the mobility of master's or doctoral graduates in the design space. However, the lack of data also means that postgraduate studies in the communication design space have not been challenged to consider mobility between academia and education, something that may change as postgraduate numbers increase. The lack of data also means that the dual purpose of generating knowledge about theory and practice should become part of the research process (Goff and Getenet 2017).

The function of South African universities is embedded in the National Development Plan (NDP 2012) with a call to decolonise the South African higher education system, not only as curricular change but also in knowledge production, validation, and transferring of knowledge to South Africans (Mbatha 2017; NDP 2012). The need to develop local design knowledge and decolonise design education has been clearly expressed in the 2017 Design Education Forum for Southern Africa's (DEFSA) conference, with a call for design education that aligns more strongly with "community, empathy, social responsibility, emancipation, collaboration, and intentional design" (Botes and Giloi 2017).

Postgraduate numbers in design

Communication Design is classified and reported in the Design and Applied Arts CESM4 (0302) second level CESM, and includes Communication or Graphic Design, Fashion Design, Industrial Design, Interior Design, Illustration, and Commercial Photography (Department of Education 2008). This second level CESM falls under the first level CESM 03: Visual and Performing Arts. Table 1 consolidates the NQF8 to NQF10 graduate numbers from 2010 to 2021 from the HEMIS Data Reports (DHET n.d.). A more granular analysis that isolates Communication Design is not possible with the available information. Also, some of the newer design fields, such as user experience (UX) design and interaction design, are not included in any current CESMs. However, despite the general nature of the CESM, a valuable snapshot is provided in Table 1.

The NQF8 numbers in Table 1 include honours, postgraduate diploma, and the four-year bachelor qualifications (480 credits). BTech qualifications (a fourth year at the previous technikons) were included as NQF8 up to 2014. The technikons provided the backbone of communication design education for many years in South Africa, and BTechs were a sought-after qualification in the design space that allowed students access to master's studies. Van Koller (2010) points out that the "abandonment" of BTechs as part of the restructuring by the HEQF from 2009 to 2014 led to a reduction in the postgraduate pipeline. Students at universities of technologies (UoT) must now complete a diploma, advanced diploma, and postgraduate diploma before access to master's studies is granted.

The NQF8 numbers flatlined again during the COVID-19 period. However, the latest available numbers show a positive and welcome upturn in both NQF8 and NQF9 numbers (see 2021 data, Table 1), with the NQF8 qualification a vital pipeline for access to postgraduate studies. There are now also honours degrees in Communication Design at five private providers of higher education. Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) is a consideration available that increases applicant access based on their industry experience. Still, generally 10 per cent of RPL applicants per cohort is allowed (translates to one in ten), and this route might not be possible with the low current numbers. The NQF10 numbers remain very low, especially considering the many design fields in the CESM.

Nine public universities in South Africa offer master's degrees for communication designers, of which one institution offers a coursework master's degree. Six universities offer doctoral degrees, two of which are professional doctorates (see Annexure 1).5 Of these six doctoral degrees, only three are exclusive to design. The other three doctoral degrees are now incorporated in "Visual Arts" or "Arts and Design", a move that contradicts the development of postgraduate design and may reflect operational capacity constraints. There are no master's or doctoral qualifications in communication design or any other design fields yet offered at private higher education institutions.

The national goal is to increase doctoral graduate numbers to be on par with Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) (Faller et al. 2023). The set target is that 75 per cent of lecturers must have a doctorate by 2030 (NDP 2012; Faller et al. 2023). The doctoral numbers in Table 1 remain very low. Mbatha (2017) points out that only 7 per cent of academic staff have doctoral qualifications in fashion design departments at South African universities (2015 data). No such data is available for communication design departments at South African universities, and such data would be greatly beneficial to set targets. The NQF10 numbers in Table 1 do not show any significant movement and require further investigation. Future research should consider the recent trend where departments now only offer one combined doctorate (design and art combinations) since reporting may be done in the visual arts CESM in future, where it may not be possible to differentiate visual arts and design graduates.

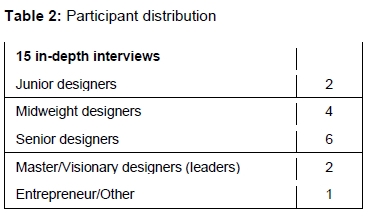

RESEARCH DESIGN

I conducted 15 in-depth, semistructured interviews with communication designers in the industry at various career levels, from junior to senior (see Table 2). Two participants are leaders in the field (based on reputation), and one is a designer who can be classified as a design entrepreneur. Participants were purposively selected to allow for a wide experience and age range. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, thematically coded, and analysed using ATLAS.ti. All identities are kept confidential.6

The interview schedule comprised background questions followed by open-ended questions on perceptions about postgraduate studies in design, how participants continue to learn, their knowledge needs, career goals, and how research is used and viewed. Questions had to be asked in a sensitive manner because what is postgraduate for one person might not be postgraduate for another, and a specific level of qualification was not a requirement for participants. Some of the key findings are briefly discussed in the next section.

FINDINGS

Theme 1: Negative perceptions and challenges

Negative perceptions about postgraduate studies outweighed positive perceptions. The most mentioned was life-family-work balance, as postgraduate studies would mean a choice between family, studies, and/or work. The industry is experienced as hard, with long hours, as expressed by Sen5:

"I'm sure it's possible [to study further]. But I think it will come at some expense in the sense of maybe not a family, maybe not kids, maybe not something like that. Because our industry is hard. There's a lot of overtime and to manage that overtime still furthering your studies, still having that amount of pressure while maintaining a managerial kind of, let's say my position where I'm at now, I don't know where I would find the time."

The second aspect frequently mentioned by participants is a lack of relevance, that their degrees are not aligned with industry and that postgraduate studies have limited value and recognition. An MBA was mentioned as having more value. Studying further is even seen as limiting your career and suitability to find employment, and you learn more at work (mentioned by all the participants). Sen5 pointed out that if you keep studying, the only place for employment would be in academia because you have not climbed the work ladder. The opinions confirm the fact mentioned by Faller et al. (2023) that one in five doctoral graduates in social science and humanities cannot find a position in their fields of study.

A comment by studio manager Mid2 stood out: "We see institutions as the machine that churns out the workers [own emphasis]. You don't necessarily see it as an institution with a wealth of knowledge, which I imagine it is, you know [...] this is the general feel, we feel like we can find everything online."

The over-specialised nature of postgraduate studies was also raised as the studies focus only on a thesis or dissertation. The nature of thesis writing is described by Master1 as "extremely problematic [...] in language in which is just insane [own emphasis] [...] that it lacks the fundamentals of communication". Academic conferences were pointed out to not deliver in terms of value, and journals are too costly, limiting access to research. When asked if she would go to a university to find data or research, one candidate mentioned that a university is not like a library you can walk into. Universities are seen as exclusive and the knowledge is not accessible. She doubted that there would be any value in research done at a university for her as a practitioner, a sentiment echoed by several of the other participants.

Conversations during the interviews often shifted to negative undergraduate experiences, with lecturers seen as unapproachable or with limited relevant skills and industry experience. Design lecturers from other disciplines, such as Fine Arts, were mentioned as not understanding the design space. All these opinions seem to fuel negative perceptions.

Three of the participants attempted master's studies and deregistered. These participants are experienced and older and mentioned that although they might consider returning to do a master's, the current lecturers who could be their supervisors are now much younger than they are, with no experience in the field. They question what they would learn. These participants described their postgraduate journeys as brutal, and they pointed out their lack of writing ability, challenges around time management, self-discipline and motivation, cost, family issues, and time constraints as factors that might prevent them from completing their studies. Also, the time allowed to complete a master's is seen as too short by these participants.

Theme 2: Knowledge and skills needs

All the participants recognised the value of ongoing development, learning, and personal growth. When probed about what knowledge and skills they need at the point where they are now, most mentions centred around business intelligence, such as management and strategy know-how, research skills, business communication, better connection with users, and client service. E1 referred to research skills as the need to determine the accuracy of design to see if the design was on target. She pointed out that this area is neglected in South African design education.

The speed of change was mentioned, and all the participants said that staying up to date with new media and software and hardware changes is part of designers' daily existence and survival. All the participants use online tutorials to stay up to date with software, and most mentioned that their workplace facilitates some form of staff development, as long as the development does not impact day-to-day productivity.

A subtheme emerged around the need for workplace and soft/life skills, such as people skills, workplace etiquette, meeting processes, business writing, and verbal and interpersonal communication. Sen2 pointed out that her career would have moved faster if she had the skill to deal better with people. Difficult-to-develop soft skills mentioned were adaptability (Sen6) and dealing with criticism (Vis1). One participant pointed out that these skills cannot be learned by watching a tutorial. How you manage yourself in a team is also revealed as a challenge by Mid 1:

"It's very important because you're trying to describe your job function when you're working [in an] interdisciplinary team and if you don't have a solid foundation for how to make that assessment, you're almost dead before you started with the project and then the designer can very easily become relegated to the sideline and not really contribute as much as what they could and then it becomes the job of the technical advisor [own emphasis]'"

Theme 3: Positive perceptions

Despite all the negative perceptions, some positives were mentioned, such as that postgraduate studies might allow you into the management level, could enable you to start your own business, clients might trust you more, and that there is value in conducting your own research. Accessibility, flexibility, and affordability are requirements for postgraduate studies. The need to contribute to society was also mentioned, and postgraduate studies are mentioned as a possibility to do just that.

On the one hand, lecturing is seen as a job opportunity and on the other is critiqued as a sheltered life where lecturers have a poor understanding of the industry - even seen as "disengaged" (Mid3, Entrepreneur1, Master1).

DISCUSSION

The interviews confirmed the gap between postgraduate studies and in-industry designers' activities. Participants clearly pointed out that postgraduate studies are not seen to be aligned with career advancement and could even hamper a designer's career. Several participants mentioned the MBA as having more value, possibly pointing to the need for a different type of master's in design, one that would address the need for business intelligence, business management, and leadership skills mentioned in the interviews. The participants' opinions confirm Meyer and Norman's (2020) viewpoint that design education needs to be redesigned at these advanced levels. The abandonment of master's degree studies by three of the 15 participants suggests that if some of the challenges they experienced could have been overcome, then the three individuals might have successfully completed their studies.

The professional master's and doctorate degrees might provide a way to increase interest in postgraduate studies in design. The purpose of presenting a professional master's degree is to educate and train graduates "who can contribute to the development of knowledge at an advanced level such that they are prepared for advanced and specialised professional employment" (CHE 2014, 38). The professional degrees aim to develop high-level performance and innovation in professional contexts, combining a high level of research capability to integrate "theory with practice through the application of theoretical knowledge to highly complex problems" (CHE 2014, 41).

Both the professional master's and doctoral degree types align postgraduate studies with industry and may contain coursework in addition to the research components. Coursework master's degrees could be less daunting for students who work full-time in industry or return to postgraduate students after a while in industry. Only one coursework master's degree was identified that offers a specialised communication design qualification (Annexure 1).

The impact of discipline drift (when communication designers move over to MBAs or other management qualifications) is unknown. The challenge for presenters of coursework and professional master's degrees in the design space would be to find lecturers and supervisors with suitable one-up qualifications and the type of experience that would add value to senior designers who return to postgraduate studies.

A development that could improve alignment in postgraduate design education is the acceptance of practice-based/led research approaches. The National Qualifications Act (South Africa 2014) and the Policy on the Evaluation of Creative Outputs and Innovations produced by public higher education institutions support practice-based/led research (De Lange and Ndlovu 2019). This type of research might better speak to designers' strengths and the nature of the discipline and research problems, as well as produce research that communicates in a language that designers can understand. Some of the master's and doctoral degrees currently registered allow for this type of research, but this may not be evident for aspirant students when looking at course descriptions.

An example of improving postgraduate design education accessibility can be seen in the European D.Doc (2022/2023) platform, where doctorates are presented as easy-to-read impact case studies with an abstract, a summary, an interview with the researcher, and a link to the thesis. This approach greatly enhances accessibility, and such approaches might shift attitudes, increase access, and present authentic postgraduate narratives.

Research skills were mentioned by several of the participants as an area for future development. The ability to conduct design research is now regularly featured as a requirement in job adverts, especially for digital communication and user experience (UX) design. This requirement for design research ability provides an opportunity for postgraduate courses to align to industry better by teaching the skills related to the type of research that industry needs.

Knowledge development requires both industry and academia and takes place through knowledge exchange (Zielhuis et al. 2022). The interviews indicate that the industry does not find value beyond the training of entry-level designers. The question is whether academic research is unaligned with no value for industry or simply not accessible. An approach to contribute to mutual value would be working collaboratively with industry on research projects. Such projects are not without challenges, such as different paradigms and research needs, for example, scientific truth versus practical utility and actionable knowledge (Zielhuis et al. 2022). Such collaborative approaches would require the academic research community to look critically at the type and purpose of knowledge generated and how knowledge is shared. Only then would postgraduate studies contribute to developing a mature discipline, one in "which academics and practitioners of various kinds share research ideas and results based on a shared domain of interest" (Poggenpohl 2015, 56).

Several of the participants referred back to shortcomings in their first qualifications. These could be in the skills taught and the lecturers not delivering on expectations or perceived as inaccessible (one participant even saw lecturers as seeing themselves on a pedestal). The suggestion is made that if undergraduate education and syllabi were to become more relevant, it would lay the foundation for postgraduate studies.

The 2017 DEFSA Conference focused on the need for design education to be decolonised to deliver regarding local needs and contexts. Authors at this milestone conference saw this decolonised curriculum as a responsibility. At this conference, Mbatha (2017), a fashion design scholar, posits that academics with doctoral qualifications are crucial to developing the decolonisation of higher education. The collaborative nature of design might also be ideally positioned to foster a decolonised approach to research, one that is not modernist according to Munro (2017, 198) and is Western regarding "legibility, measurability, and predictability", but lies in the "empathic and intimate engagement through collaboration and strategic alliances with the future - in the pursuit of making a better life". As such, a design and research agenda can be aligned. However, five years on, no significant shift in the number of master's and doctoral degrees exists, and it is unclear if academia is cultivating sufficient leadership and the young postgraduate scholars required to advance undergraduate curricula.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The literature, graduate numbers, and industry perceptions point to a common challenge: that the design discipline, and more specifically communication design, should grow capacity in the postgraduate space. This study revealed industry perceptions that confirmed the gap in the alignment between postgraduate studies and industry and also provided insights that challenge the core of postgraduate and undergraduate education, as well as the research produced by academia. This gap could increase if research production is misaligned, is seen as having no relevance and value, and is not accessible. The study also shows that the gap is systemic with many dimensions, starting with the core of design education at the undergraduate level, where the foundation for lifelong learning should be created, as well as a respect for design knowledge and research. Further challenges include considering who lectures and supervises at postgraduate levels, and this may be the biggest challenge, since potential postgraduate students expect lecturers who, in addition to theoretical knowledge, also know and understand the industry.

The challenges suggest recommendations that would firstly consider the pipeline, as well as the nature and value proposition, of each of the NQF levels, and secondly consider the mutual benefit of each postgraduate level. The first recommendation is to explore the nature and possibilities of the various models and approaches available that would benefit both academia and industry. For example, how would a professional master's and doctoral degree in the communication design space differ from a research master's or doctoral degree, and how would we incorporate and manage practice-based and practice-led research approaches? A second recommendation suggested is to explore better ways of making research accessible, and a third recommendation is for more research and tracking of alums in the design space (to understand career progression, career needs, and, if unsuccessful in graduating, the reasons for non-completion). Lastly, the fourth recommendation is to recognise that the NQF8 level is a particularly important enabler or bridge to master's and doctoral levels and should be grown in size and scope.

The insights developed in this study would have remained hidden without the interviews. We should have more such conversations that establish the means to share meaningful knowledge in an accessible way to narrow the gap between industry and academia. Only then can academia earn a place in industry beyond the supply of entry-level communication designers. There is much to learn and do!

NOTES

1 In South Africa an undergraduate lecturer needs a qualification one NQF level higher than what they are teaching. To teach degrees (NQF7) a lecturer needs an NQF8 qualification.

2 Partly based on a doctorate completed at Da Vinci Institute: HM van Zyl, 2018. The development of a framework for postgraduate studies in communication design. All thanks to my supervisor, Dr Loffie Naude.

3 If a creative artefact, design outcome or process is the basis of the contribution to knowledge, the research is referred to as practice-based in this article. If the research aims to develop new understandings about design practice, it is practice-led. However, these terms are often used interchangeably in the literature with different meanings.

4 Classification of Educational Subject Matter (CESM)

5 The six doctoral degrees were counted based on SAQA website and institutional webpages when the article was written. This is a developing space, with universities of technologies still replacing MTechs with MAs.

6 Ethics approval was obtained from the Da Vinci Institute.

REFERENCES

Botes, H. and S. Giloi. 2017. "Foreword." In Proceedings of the 7th DEFSA Conference #Decolonise, 27-29 September. Pretoria. https://www.defsa.org.za/2017-defsa-conference. [ Links ]

Boughey, C. and S. McKenna. 2021. Understanding Higher Education: Alternative Perspectives. Cape Town: African Minds. [ Links ]

CHE. 2022. "Doctoral Degrees National Report." Council on Higher Education. https://www.che.ac.za/publications/programme-reviews/release-doctoral-degrees-national-report-march-2022A. [ Links ]

CHE. 2014. "Framework for Qualification Standards in Higher Education." Council on Higher Education, Government of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201410/38116gon819.pdf. [ Links ]

Corazzo, J. H., R. G. Honnor, and A. S. Rigley. 2019. "The Challenges for Graphic Design in Establishing an Academic Research Culture: Lessons from the Research Excellence Framework 2014." The Design Journal 23(1): 7-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1682446. [ Links ]

D.Doc. 2022. "Mapping of the European Doctorate in Design." https://d-doc.eu/. [ Links ]

De Lange, R. and R. Ndlovu. 2019. "Assessment of Postgraduate Studies: Are We Missing the Mark?" In Proceedings of the 8th International DEFSA Conference, 9-11 September. Cape Town. https://defsa.org.za/system/tdf/downloads/DEFSA2019ProceedingsLowRes.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=313&force=. [ Links ]

Department of Education. 2008. "CESM Classification of Educational Subject Matter." Department of Higher Education and Training. https://www.dhet.gov.za/_Management_and_Information_Systems/CESM_August_2008.pdf. [ Links ]

DHET. n.d. "HEMIS Data Reports: Graduate Tables." Department of Higher Education and Training. https://www.dhet.gov.za/sitepages/higher-education-management-information-system.aspx?rootfolder=%2fhemis%2fgraduates&folderetid=0x0120001a2e7183ba3e3b44bfa35eeda2510d0b&view=%7bd5edeb6c-4bfc-4717-8c3a-86010348adea%7d. [ Links ]

Faller, F., S. Burton, A. Kaniki, A. Leitch, and I. Ntshoe. 2023. "Achieving Doctorateness: Is South African Higher Education Succeeding with Graduate Attributes?" South African Journal of Higher Education 37(2): 93-108. [ Links ]

Frascara, J. 2022. "Revisiting 'Graphic Design: Fine Art or Social Science?' - The Question of Quality in Communication Design." Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 8(2): 270-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2022.05.002. [ Links ]

Goff, W. M. and S. Getenet. 2017. "Design Based Research in Doctoral Studies: Adding a New Dimension to Doctoral Research." International Journal of Doctoral Studies 12: 107-121. https://doi.org/10.28945/3761. [ Links ]

Griffin, D. 2016. "Doctoral Education in (Graphic) Design." Dialectic 1(1): 135-154. https://doi.org/10.3998/dialectic.14932326.0001.109. [ Links ]

Lange, J. and J. Eeden. 2016. "Designing the South African Nation from Nature to Culture." In Designing Worlds: National Design Histories in an Age of Globalisation, edited by Kjetil Fallan and Grace Lees-Maffei, 60-75. New York: Berghahn Books. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv8bt1mv.7. [ Links ]

Mbatha, S. 2017. "Research Sleeping Dogs in Fashion Design Departments of South African Universities: A Decolonisation Obstacle?" In Proceedings of the 14th National DEFSA Conference, 27-29 September, 159-168. Pretoria. https://www.defsa.org.za/sites/default/files/downloads/DEFSA2017Proceedings15-12-2017_0.pdf. [ Links ]

Meyer, M. W. and D. Norman. 2022. "Changing Design Education for the 21st Century." She Ji : The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 6(1): 13-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.12.002. [ Links ]

Munro, A. 2017. "Doing Research to Decolonise Research: To Start at the Very Beginning." In Proceedings of the 14th National DEFSA Conference, 27-29 September, 190-201. Pretoria. https://www.defsa.org.za/sites/default/files/downloads/DEFSA2017Proceedings15-12-2017_0.pdf. [ Links ]

NDP. 2012. "National Development Plan 2030: Our Future - Make It Work Available." National Development Plan of the Government of South Africa. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/ndp-2030-our-future-make-it-workr.pdf. [ Links ]

Poggenpohl, S. H. 2015. "Communities of Practice in Design Research." She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 1(1): 44-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2015.07.002. [ Links ]

Redström, J. 2020. "Certain Uncertainties and the Design of Design Education." She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 6(1): 84-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2020.02.001. [ Links ]

Sarrico, C. S. 2022. "The Expansion of Doctoral Education and the Changing Nature and Purpose of the Doctorate." Higher Education 84: 1299-1315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00946-1. [ Links ]

Singh, S., N. Lotz, and E. B.-N. Sanders. 2018. "Envisioning Futures of Design Education." Dialectic 2 (1): 19-46. https://doi.org/10.3998/dialectic.14932326.0002.103. [ Links ]

Van Koller, J. F. 2010. "The Higher Education Qualifications Framework: A Review of Its Implications for Curricula." South African Journal of Higher Education 24(1): 157-174. [ Links ]

Van Zyl, H. M. and L. Carstens. 2023. "Communication Design Industry - in Search of Unicorns or New Pathways?" In Proceedings of the 17th National DEFSA Conference, 21-22 September, 7182. Pretoria-hybrid. [ Links ]

Voûte, E., P. J. Stappers, E. Giaccardi, S. Mooij, and A. Boeijen. 2020. "Innovating a Large Design Education Program at a University of Technology." She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, andInnovation 6(1): 55-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2019.12.001. [ Links ]

Zielhuis, M., F. S. Visser, D. Andriessen, and P. J. Stappers. 2022. "Making Design Research Relevant for Design Practice." Design Studies 78(Jan): 101063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2021.101063. [ Links ]