Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Higher Education

versión On-line ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.38 no.1 Stellenbosch mar. 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/38-1-6270

SPECIAL SECTION

Balanced-integration: a dimension of supervision to support students navigating parenthood in pursuit of a PhD

S. Nkoala

Linguistics Department, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3863-7392

ABSTRACT

This article explores the experiences of doctoral students juggling parental and professional roles. It proposes a balanced-integration approach in the reflective supervisor framework to tailor support. The research focuses on identifying challenges and evaluating the approach's effectiveness, suggesting supervisors should serve as advocates for well-being and motivation. With the South African government's National Development Plan aiming for a higher education sector that can produce more than 100 doctoral graduates per one million of the population by 2030, it is imperative to understand PhD student's simultaneous identities as parents and professionals who must balance the demands of their studies, families and careers. The study advances a balanced-integration approach for supervising this demographic, with supervisors serving as advocates for the holistic well-being of these students, architects of personalised academic pathways, and catalysts for motivation inspired by family commitments. This approach adds a fifth dimension to Pearson and Kayrooz's four factors of facilitative supervisory practice. The methodology is a descriptive quantitative study research design and a cross-sectional approach based on online surveys completed by 47 respondents from 13 South African higher education institutions and eight from abroad (n = 55).

Keywords: balanced-integration, supervision, parenting, doctoral studies, PhD

BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION

There is an adage in academia that getting a PhD is like having a baby: it is a long and painful process, and the end of one part of the journey is the beginning of a lifelong voyage. While imperfect, this analogy resonates, especially as many pursue a doctorate alongside parenting. The global expansion of doctoral education, with its ambitious targets, underscores the need to comprehend the dual roles of doctoral students as parents and professionals. According to Moors, Steward and Malley (2022), there has been a notable increase in postgraduate enrolment among women in the United States. Additionally, Moors et al. (2022) find a growing trend of individuals pursuing graduate education later in life, usually as parents. This points to a need to understand doctoral students' simultaneous identities as parents and professionals who must balance the demands of their studies, families and careers. Supervisors, in particular, need to be cognizant of some of the invisible factors that shape who their students are personally and professionally, and they must give due consideration to the contexts that they operate in because their interpersonal relationship with these doctoral candidates is central to the success of the academic project (Mainhard et al. 2009). Chief among these is the work-family-career dynamic, in light of a considerable number of graduate students being at significant junctures in their careers and at the peak of their childbearing years in the course of their doctoral studies (Springer, Parker, and Leviten-Reid 2009).

In South Africa, the government's National Development Plan aims for a higher education sector that can produce more than 100 doctoral graduates for every one million people by 2030 (National Planning Commission: Republic of South Africa 2012, 319), a goal that has seen higher education institutions undergoing significant changes over the past decade to increase access. Among these is the transformation of student cohorts (Leitch et al. 2022). For example, statistics reveal that a significant proportion of doctoral students in South Africa are aged 19 to 49, coinciding with childbearing and child-rearing years (Figure 1). Understanding and supporting these multifaceted identities is crucial in this changing higher education landscape. However, an advanced search on the database EBSCOhost of the Boolean (parent AND [PhD students or doctoral students] "South Africa"] yielded two results, compared to the 1 765 hits one gets when searching for the Booleans without including South Africa, indicating minimal scholarship that has considered the issue in this context.

Amidst changing demographics of doctoral students, crucial support measures lag, as revealed by the 2022 Council on Higher Education's National Review of South African Doctoral Qualifications (2020-2021) report, which states,

"In some universities, notably large comprehensives and [universities of technology], Panel Reports indicated that many students find themselves with personal problems (e.g., financial, family, accommodation, access to campus issues, etc.) .... Such difficulties undoubtedly lead to delayed completion of doctoral studies and, in many cases, result in the student dropping out of the programme."

The findings indicate a lack of deliberate efforts to create conducive institutional environments for doctoral students, contributing to delayed completion and heightened dropout rates, particularly among those facing personal challenges (Leitch et al. 2022, 48). The Academy of Science of South Africa (2010, 16) reinforces this, identifying the age of students at enrollment and competing professional and family commitments as significant risk factors for attrition in South African doctoral programmes. McAlpine, Skakni and Pyhaltö (2022) highlight the importance of achieving a work-life balance for parent-students in the decision to discontinue doctoral studies. Considering the interpersonal dynamics between supervisors and students, an awareness of the invisible factors shaping students' personal and professional lives is crucial (Mainhard et al. 2009). The work-family-career-studies relationship, especially relevant for students navigating significant career milestones and childbearing during their doctoral studies, requires careful consideration by supervisors (Springer et al. 2009).

AIM AND OBJECTIVES

This study explores the experiences of doctoral students juggling parental and professional roles. It proposes a balanced-integration approach in the reflective supervisor framework to tailor support. The research focuses on identifying challenges and evaluating the approach's effectiveness, suggesting supervisors should serve as advocates for well-being and motivation. It shows that time management, flexible work arrangements and effective communication are crucial.

STATEMENT OF PROBLEM

The conventional doctoral supervision model, centred on academic guidance, overlooks the distinct needs of doctoral students who are parents and employees. Balancing academic, parental and professional responsibilities poses unique challenges for this cohort. The current supervisory approach is inadequate in acknowledging and tackling these challenges, resulting in heightened stress, reduced motivation and elevated non-completion risks. This study aims to fill this scholarly gap by investigating challenges and proposing a balanced-integration approach within the reflective supervisor framework, enhancing supervisory practices and institutional support.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Literature on university students as parents (Webber and Dismore 2021; Manze et al. 2022; Crispin and Nikolaou 2019) reveals particular challenges for doctoral students who are also employed parents. Balancing academic, family and professional demands poses unique difficulties, with time management emerging as a predominant challenge. Juggling multiple deadlines, childcare, and long work hours is common. Stress from unsupportive employers unwilling to reduce workloads adds to these students' hurdles.

The literature highlights a negative perception of parenthood, especially motherhood, in academia (Morgan et al. 2021; Lutter and Schroder 2020). According to Moreau and Kerner (2015), marginalising parent-students results in inadequate policies, forcing students to forgo provisions like maternity leave or childcare funding. This lack of support influences supervisors' perceptions, as traditional ideals of who a doctoral student is and what they should be capable of doing persist despite sector transformations. By perpetuating the notion of an ideal student as "male, white, middle class, and unencumbered by domestic responsibility" (Brooks 2013), supervisors end up using unsuitable supervision approaches, further disadvantaging student-parents.

This literature predominantly examines global North contexts, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom, focusing on challenges faced by undergraduate mothers. A critical gap exists in scholarship, neglecting perspectives from countries in the global South, like South Africa, or from graduate students. Notably, two South African studies highlight constraints female graduate students face rooted in socio-cultural beliefs and financial hurdles. The first, examining the lived experiences of female graduate students at a specific South African university, finds that overwhelming constraints acknowledged by respondents were based on "socio-cultural beliefs rooted in traditional and religious affirmations, financial impediments and balancing their educational pursuit with traditional role expectations within their gendered familial domain" (Alabi, Seedat-Khan, and Abdullahi 2019, 1). Secondly, Herman's (2011) research reveals personal issues as a major obstacle to doctoral completion. Herman's study underscores the necessity of exploring various obstacles and their implications for supervisory support in the South African context. South Africa's doctoral student profile has shifted from primarily white males with ideal work setups to a diverse parent-professional cohort (Academy of Science of South Africa 2010). This demographic change calls for a revised supervisory approach that extends beyond academic guidance. Studies on South African doctorates suggest that non-completion is often linked to personal challenges, underscoring supervisors' need for more comprehensive support in navigating these hurdles (Academy of Science of South Africa 2010).

This study examines the experiences of doctoral students navigating parenthood and professional commitments, aiming to identify the unique challenges and opportunities inherent in simultaneously raising children and pursuing a doctoral qualification. The aim is to offer insights for supervisors dealing with candidates in this dual role. While existing scholarship primarily concentrates on academic support, it is crucial to acknowledge the centrality of personal factors. Models supporting students in managing family and work life are essential (Gill and Burnard 2008). The article contends that personal and professional aspects must be viewed holistically, challenging the tendency to separate these identities. In the existing literature, a proposition is made that good supervisors are active researchers who have developed expertise within their subject area and through the research methodologies applicable to their field (Lee 2019; Walker and Thomson 2010). However, it is reasonable to argue that being a good researcher does not necessarily mean someone will make a good supervisor.

Borders (1994, 1) suggests that a good supervisor is "empathic, genuine, open, and flexible. They respect their supervisees as persons and as developing professionals, and are sensitive to individual differences (e.g., gender, race, and ethnicity) of supervisees". This is because a key part of their success is vested in their students' success. Gill and Burnard (2008) propose that adequate supervision involves encouragement, advice, support, appraisal, pastoral care and fostering independent thinking. Recognising their students' diverse roles, including parenthood or professional commitments, requires supervisors to extend beyond academic expertise. Balancing these aspects is integral to comprehensive doctoral student support. This does not imply supervisors are responsible for intervening directly but underscores the benefit of empathy in understanding the challenges of student-parents engaged in doctoral studies while managing professional commitments. The proposed framework in this study builds upon Pearson and Kayrooz's (2004) reflective supervisor model, introducing a balanced-integration factor that encourages supervisors to support student-parents in achieving a balanced integration of academic, parental and employment responsibilities.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK: THE REFLECTIVE SUPERVISOR

Pearson and Kayrooz (2004, 99) emphasise the critical role of adequate supervision in postgraduate student satisfaction and successful degree completion. Their conceptual framework defines research supervision as a facilitative process encompassing expert coaching, facilitating candidature, mentoring and sponsoring (Pearson and Kayrooz 2004, 100, 103, 105).

1. Expert coaching involves the supervisor guiding the student in research expertise, methodology and thesis writing.

2. Facilitating the candidature entails the supervisor aiding the student in managing processes and staying on track.

3. Mentoring sees the supervisor assisting in clarifying personal and career goals and fostering relationships.

4. Sponsoring involves providing access to resources and opportunities essential for research success.

These dimensions collectively form a comprehensive model for effective postgraduate research supervision. However, in these four dimensions, a gap exists in guiding supervisors in supporting doctoral student-parents facing unique challenges. While mentoring appears most relevant, its description lacks emphasis on the psychosocial skills and support deemed essential for students' needs, as highlighted in the literature (Pearson and Kayrooz 2004, 104).

Incorporating the balanced-integration dimension proposed by this paper is crucial to filling this notable gap in the current supervisory framework. Explicitly addressing the unique challenges faced by students managing doctoral studies, parenting and employment, this dimension recognises intricate issues in time management, emotional well-being and work-life balance. Existing supervisory roles lack dedicated attention to these aspects. This addition aims to enhance the relevance and supportiveness of Pearson and Kayrooz's (2004) supervisory framework.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY

This study uses a descriptive quantitative design to explore the experiences of doctoral students who are parents and employed professionals. Adopting a cross-sectional approach, data were gathered from respondents who participated in an online survey (n=55). Ethical clearance preceded survey distribution on platforms like Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn. The study focused on recruiting individuals who were employed and who had at least one child. They had to either have completed or be busy with their doctoral studies. The questions respondents were required to complete incorporated biographical details, quantitative queries and qualitative prompts.

BIOGRAPHICAL DATA PRESENTATION AND ANALYSIS

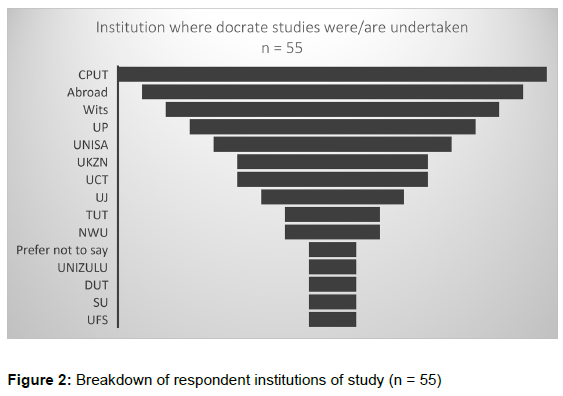

The biographical data collected from survey respondents provide insights into the characteristics of doctoral student-parents and employed professionals who participated in this study. Data include respondents' age, gender, nationality, highest level of education, field of study, employment status, parental status and number of dependents. The survey garnered responses from participants affiliated with 13 of the 26 (50%) public higher education institutions in South Africa and contributions from respondents associated with higher education institutions in other countries, as illustrated in Figure 2. It is important to note that the researcher did not predetermine the selection of these universities; rather, voluntary responses were received to the online survey distributed on social media. The diverse representation reflects the survey's reach on social media platforms and the willingness of individuals from various institutions to contribute to this study.

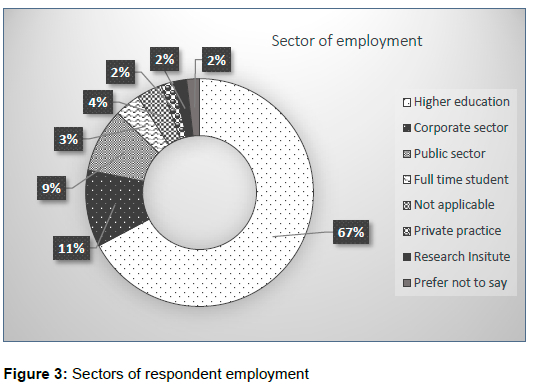

Figure 3 shows that two-thirds of the respondents were employed in higher education, with approximately 10 per cent in private and public sectors. Smaller percentages in categories like full-time students and private practice showcase additional diversity, alluding to challenges for student-parents and employees extending beyond academia, encompassing various sectors.

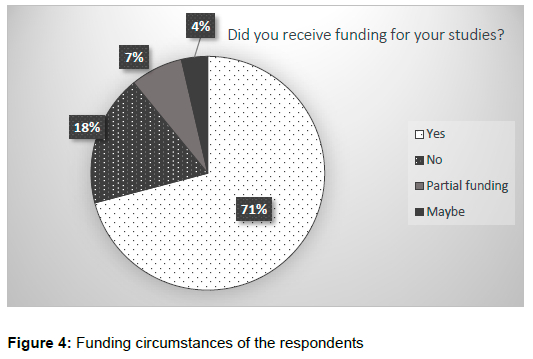

Figure 4 depicts the funding circumstances of the respondents. The majority (71%) reported receiving funding for their doctoral studies, while 18 per cent stated no funding. A smaller portion (7%) received partial funding, and 4 per cent were uncertain ("Maybe"). The distribution paints a mixed picture - while a significant number benefit from funding, a noteworthy proportion navigate their studies without financial support, which no doubt influences their academics.

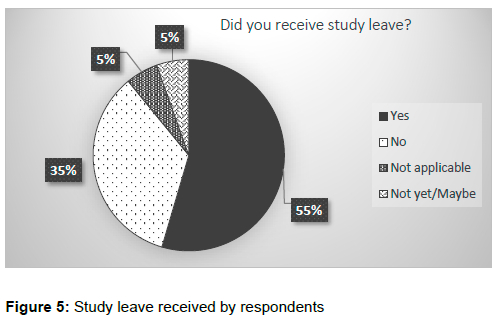

Figure 5 reveals that 55 per cent of respondents received study leave during their doctoral studies, while 35 per cent did not, signifying a significant subset managing studies without this institutional support. Another 5 per cent responded "Not applicable", indicating possible ineligibility or unique circumstances. Additionally, 5 per cent responded "Not yet/Maybe", suggesting uncertainty or anticipation of study leave in the future.

Figures 4 and 5 show that many respondents, predominantly from the higher education sector, received funding and study leave. Varied durations - from a few days to several months - were reported. The higher education sector offers more funding opportunities, and study leave is a standard provision in employment contracts, contributing to these observed patterns. However, this is not always the case for those in other sectors.

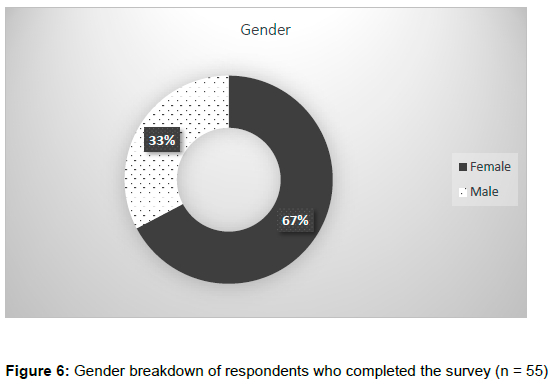

Figure 6 presents the gender breakdown of the 55 survey respondents: two-thirds identified as female and one-third as male. Despite options for non-binary and open responses, no respondents chose these.

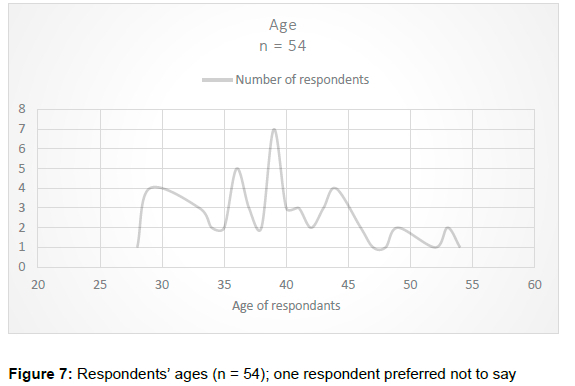

In Figure 7, respondents' ages (n = 54) are presented. One participant opted not to disclose. The distribution spans 28 to 54 years, reflecting diverse life stages.

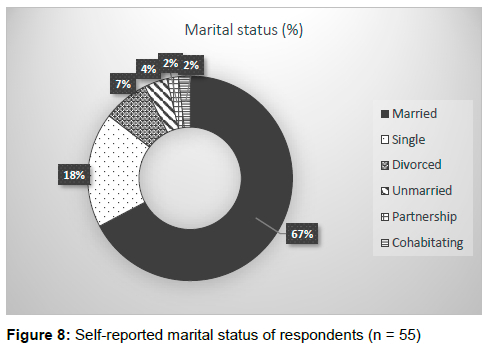

According to Figure 8 which details the self-reported marital status of the respondents, most (67%) reported being married, emphasising a significant representation of individuals in committed partnerships - approximately 18 per cent identified as single. A smaller percentage (7%) reported being divorced, 4 per cent identifying as unmarried, and 2 per cent each in partnership and cohabitating statuses. The question was posed in light of the overwhelming finding in the literature that marital status is an important consideration (Crawford and Windsor 2021). Obviously, some categories, such as "single" and "divorced", could overlap, but it was up to the participants to self-report based on the marital status that they felt best described them.

The findings from Figure 8 demonstrate the variety of marital status among respondents, offering insights into the complex interplay between personal relationships and the pursuit of doctoral studies. The substantial representation of married respondents shows the prevalence of committed partnerships within this demographic, suggesting that a significant portion of student-parents undertaking doctoral studies concurrently navigate the challenges of academic pursuits alongside the responsibilities and dynamics of married life. The 4 per cent identifying as unmarried and the 2 per cent each in partnership and cohabitating statuses further nuance the understanding of relational dynamics within this demographic.

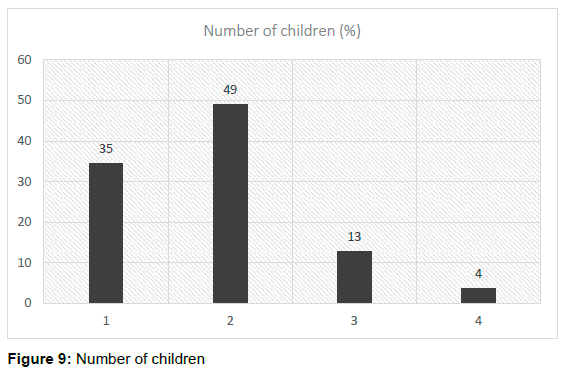

Figure 9 depicts respondents' family sizes, showing half have two children, over a third have one child, and around one in five have three or more children. This highlights a subset of students dealing with the additional responsibilities of larger families.

The number of children significantly influences the academic journey of student-parents pursuing doctoral studies. For the 65 per cent with two or more children, balancing academic and parenting duties poses a pronounced challenge, potentially restricting study and research efforts (Brooks 2013). The presence and number of children impact support system availability, affecting stress levels and work-life balance (Andrewartha et al. 2023). Larger families may provide built-in support but heighten stress due to increased parenting duties, financial strain and complex time management, while smaller families may require greater reliance on external networks.

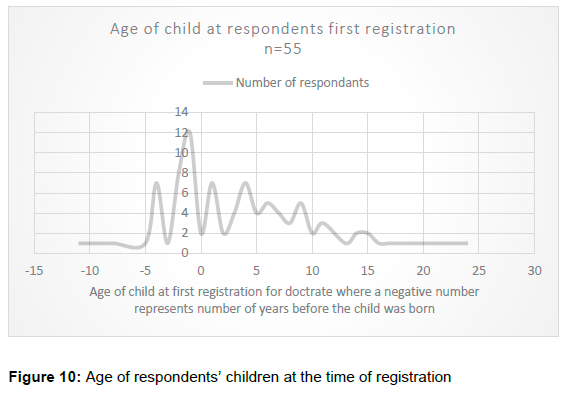

Figure 10, a graphical representation of respondents' children's ages at registration, accounts for the birth years of each respondent's child(ren). Calculations determined the age difference between each child's birth year and the participant's registration year. For instance, two participants had children born the same year they registered for doctoral studies (y-value at 0 on the x-axis). Twelve registered a year after a child's birth (y-value at -1 on the x-axis). One enrolled 21 years after their first child's birth (y-value at 21 on the x-axis), and another began studies 11 years before their child's birth (y-value at -11 on the x-axis).

Most respondents had young children around the time of their initial doctoral registration, clustering around 0 on the x-axis. This pattern indicates that student-parents are often navigating early parenthood during the start of their doctoral journey. Balancing childcare, sleepless nights and child development with the intellectual rigour of doctoral pursuits likely characterised this group (France-Kelly 2022).

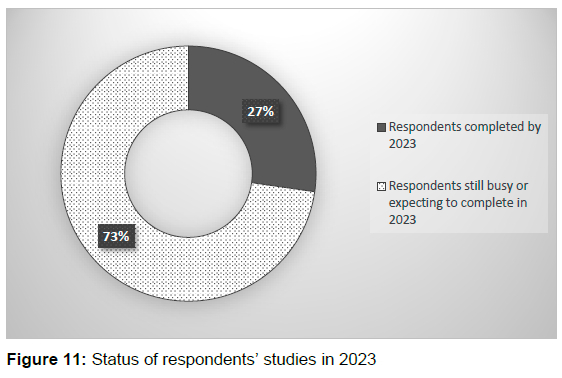

Figure 11 below provides an overview of the current status of respondents' doctoral studies as of January 2023. The figure delineates two categories: those who have completed their doctoral studies and graduated, constituting 27 per cent of the respondents, and those still actively engaged in their academic endeavours or anticipating completion in 2023, which includes the remaining 73 per cent. This figure shows that around a quarter of the student-parents who responded to the survey completed their studies, demonstrating the feasibility of balancing doctoral studies with parenting and achieving this notable academic milestone while navigating familial and professional duties. The larger cohort (73%) remains actively engaged or anticipates completion in 2023.

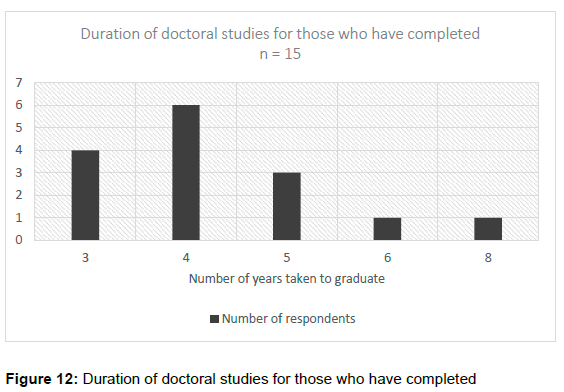

Figure 12 provides a graphical representation of the amount of time taken by the 27 per cent (n = 15) of the respondents who had completed their doctoral studies by January 2023 to do so. Notably, the majority finished within four years, with six completing in this timeframe. Additionally, four concluded in three years, three in five years, and one each in six and eight years.

Contrary to assumptions, the information in Figure 12 challenges the notion that student-parents in doctoral studies face extended durations. The majority concluded their journeys in a reasonable amount of time, challenging generalisations and emphasising the need to acknowledge individualised experiences in doctoral education.

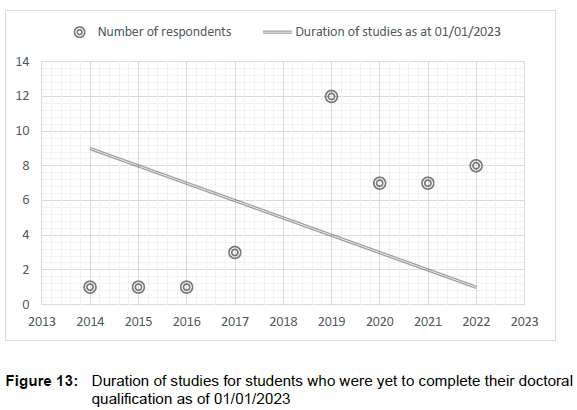

Figure 13 reveals a similar pattern for respondents yet to graduate. Of the 75 per cent of the respondents who were still busy with their studies (n = 40), 85 per cent had studied for four years or less by 1 January 2023. Ten per cent of the total (n = 55) surveyed had been studying for six years or more and were still in progress. This pattern aligns with the notion of relatively shorter study durations for the majority.

Figures 12 and 13 contend with the prevailing literature on parents in doctoral studies, often emphasising delayed completion due to challenges. While acknowledging difficulties in detailed responses, none of these respondents reported dropping out. Data suggest that a notable number completed their studies within a reasonable timeframe, an aspect explored in the following section on respondents' perspectives on work and childcare support during their studies.

Forms of support

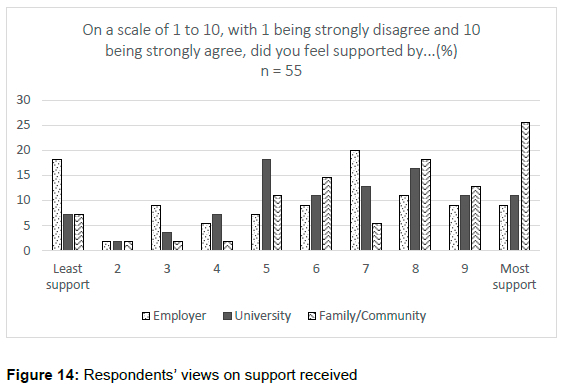

Using a Likert scale, respondents assessed support levels from employers, universities and family/community (Figure 14). Most strongly felt family/community provided the most significant support, aligning with prior research emphasising the crucial role of these networks for doctoral students (Alabi et al. 2019; Andrewartha et al. 2023; Manze et al. 2022). Responses regarding support from employment varied, with almost as many choosing "strongly disagree" (option 1) as "considerable support" (option 7). Regarding support from the institutions where their studies were/are being undertaken, most indicated neutrality (option 5), which is surprising given universities' perceived role in doctoral support.

Considering literature emphasising childcare and work challenges for doctoral student-parents (Andrewartha et al. 2023; Alabi et al. 2019; Springer et al. 2009), respondents detailed their support sources as depicted in Figure 15. A significant percentage (76%) relied on spouses or partners, followed by relatives (55%). Formal structures were also used, with 33 per cent involving children's schools and 31 per cent hiring childminders. Some sought assistance from older children. This indicates a reliance on familial and formal networks to navigate childcare and work challenges during doctoral studies.

The substantial reliance on spouses or partners underscores the crucial role of intimate relationships in facilitating the academic journey of student-parents. Shared responsibilities in childcare, household duties and emotional encouragement contribute to a conducive environment for academic pursuits (Manze et al. 2022). In the context of changing demographics within doctoral education, where student cohorts increasingly reflect diverse family structures and responsibilities, the fact that more than half the respondents relied on extended family members highlights the adaptability of support systems, suggesting that family, beyond the immediate nuclear unit, play a crucial role in shaping academic experiences and outcomes of student-parents.

Conversely, concerning workload support in their places of work, almost 80 per cent, or four of every five respondents, indicated they had no assistance (Figure 16). Data reveal that a substantial percentage (78%) did not receive any help with their work; 9 per cent had a replacement staff member brought in, and an equal percentage sought support from colleagues; 7 per cent reported reduced work hours, taking an income cut; and 5 per cent were unemployed during their doctoral studies. The smallest percentage (2%) relied on a "Connecticator" for personalised assistance.

The absence of tailored institutional frameworks from employers may explain the high percentage (78%) of student-parents independently managing their workload (Figure 16). Institutions might lack protocols for flexible work arrangements, reduced hours or supportive measures addressing student-parents' unique challenges. However, respondents with replacement staff, colleague support or reduced work hours are evidence of workplaces recognising and accommodating individual needs. The 5 per cent not employed may have chosen to prioritise academics over income during their studies. Alternatively, they may have never worked. The data collected did not ascertain this. Overall, these findings underscore the urgency for institutions to establish comprehensive policies supporting student-parents' work-life balance during doctoral studies.

Perspectives on challenges and rewards

For the qualitative questions of the survey, respondents were asked to describe the most challenging and rewarding aspects of their doctoral studies while parenting and working. This was posed in the form of open-ended questions. Figure 17 provides a frequency graph of relevant keywords related to challenges. Figure 18 presents a frequency graph capturing words associated with rewards.

The most prominent words related to the challenges by a large margin were "work" and "time", while those related to the domestic context, such as "home", "parenting", and "child" care, are notably fewer. A closer reading of the responses in this regard unveils themes related to internal and external challenges encountered by the respondents. Internal challenges refer to the emotional and psychological toll the respondents bear regarding their inner worlds. Emotional distress, feelings of guilt and physical fatigue are fundamental internal forces emerging from respondent reflections.

As articulated by a female respondent who embarked on her academic pursuit in 2009 and graduated in 2013, the intersection of academic commitment and personal life for her was not devoid of emotional tribulations: "Emotional and psychological well-being was affected, went through a divorce at the beginning of my studies, followed by clinical depression".

Other respondents spoke of a pervasive sense of guilt as they grappled with falling short in dedicating themselves effectively to their various roles as students, parents and employees. A female participant who registered in 2017 and graduated in 2020 admitted struggling with the "guilt of not being able to apply myself fully to any of these responsibilities".

There was also a reference to the physical fatigue respondents experienced from burning the candle at both ends as they strove to ensure they did not drop any balls. A male respondent, who commenced his journey in 2017 and expects to complete his studies in 2023, vividly depicted this phenomenon: "Tiredness. Sleeping with the kids who wake up frequently. I was both a 'stay at home' dad and a full-time PhD student". This profound physical fatigue had a ripple effect in other areas of their lives.

Conversely, external pressures encompass the array of challenges emanating from respondents' environments, including familial responsibilities, financial constraints and employment demands. The challenge of balancing family responsibilities with academic and work commitments was a significant theme in the reflections. A male respondent who started in 2019 and expects to graduate in 2023 shared,

"setting aside time to bond with my baby as well as helping my wife. I feel I strained her, and this made me really sad. At one point, she got sick, and I feel I contributed to that. I should have helped her more, but I was trying to balance everything."

A female respondent who also registered in 2019 and expects to graduate in 2023 said, "Important to note also that it is not just parenting demands but family responsibilities too because one is a sister, aunt and daughter".

The strain of financial pressure was another layer of complexity, as some respondents wrote about balancing educational pursuits, parenting and work against constrained finances. A male participant, who started his doctoral studies in 2022 with an expected graduation in 2024, acknowledged, "The most challenging thing is balancing work, studying and parenting. Finances were the biggest challenge; can't quit work to concentrate on studies, yet work takes study time".

The financial pressures underscore the structural dimension of this journey, highlighting the intersection of economic constraints and participant aspirations. These challenges were closely tied to work demands placed on respondents. In this regard, a female participant whose journey spanned from 2015 to an anticipated graduation in 2023 noted that for her, the biggest challenge was "balancing the workload with parental and family responsibilities, and doing all of it well".

This sentiment resonates with another female respondent whose studies began in 2021 with graduation projected for 2024: "The high workload, in terms of work responsibilities, is a challenge".

Figure 18 presents a frequency table capturing words associated with rewards experienced by the respondents.

In terms of the frequency table related to respondents' descriptions of what they found most rewarding about being doctoral students as well as parents, the words featuring most prominently were "PhD", "family", and "children". A close read of these responses unveils respondents' reflections on rewards experienced: the deep sense of accomplishment and inspiration derived from their concurrent pursuit of a doctoral degree, parenting and employment responsibilities. This highlights the motivational power of personal achievement and its capacity to catalyse academic and personal growth. As one respondent stated, "Inspiring my kids to study further ... they see me reading and writing so everyone in the house has homework". Studying and striving for higher education is a source of motivation for respondents and their children.

Respondents noted that dedication to their studies further resonated with their children, fostering a culture of education within their households. One respondent explained, "Being an example to others that you can still be a mother and complete your education". The respondents recognise themselves as role models, breaking traditional moulds and challenging societal expectations. The achievement of a doctoral degree while simultaneously parenting and working serves as a testament to their determination, inspiring their children and the broader community - the intergenerational impact of pursuing a doctoral degree while parenting was linked to this. One respondent noted, "My kids celebrating my success with me... able to care for their future". Studying, reading, and writing are shared family experiences, creating an environment that nurtures curiosity and love for learning. One respondent said, "Kids get motivated to study when they see me studying as well ... for a culture of reading in my family".

DISCUSSION

Based on these findings, this article proposes including a fifth role to Pearson and Kayrooz's framework (2004), namely the balanced-integration role in supervisors. The proposed dimensions of this balanced-integration role are as follows:

1. Holistic well-being advocates: Supervisors take on the role of advocates for the holistic well-being of student-parents. This involves recognising and addressing not only academic challenges but also considering the broader aspects of student life, encompassing personal and family well-being.

2. Designers of customised academic pathways: In the balanced-integration approach, supervisors act as designers of customised academic pathways. This implies a tailored and flexible approach to accommodate the specific needs and challenges of student-parents, recognising the individuality of each student's academic journey.

3. Catalysts for family-inspired motivation: Supervisors serve as catalysts for family-inspired motivation. This involves acknowledging and leveraging the motivating factors arising from familial commitments, encouraging a positive and supportive environment that fosters both academic and personal growth.

This framework envisions supervisors not only as academic guides but also as partners in navigating the complex intersection of academic pursuits, parenting responsibilities and professional commitments. The balanced-integration approach seeks to bridge the gap between academic guidance and the unique challenges of student-parents, fostering a supportive and inclusive supervisory environment.

Supervisors as holistic well-being advocates

Regarding the first dimension, in which supervisors serve as advocates of holistic well-being on the part of their students, the biographical data provided earlier offer a comprehensive glimpse into respondent profiles. Most individuals surveyed were women, primarily employed in the higher education sector, who benefited from funding and leave to support their studies. Data also revealed that many respondents were relatively young, with a majority having two children and entering their doctoral studies while already parents. This transformation in the profile of doctoral students, from previously being white males with minimal familial responsibilities, underscores the importance of redefining supervisory approaches to cater to this changing demographic. In contrast to the traditional view that downplayed the roles of parenting and working, these findings emphasise the significance of equipping student-parents with skills and strategies critical to navigating multiple roles effectively. The argument advanced is that as the student demographic has changed, the supervisors' understanding of their roles needs to change to best support the students they have rather than those they would have previously had.

Within the balanced-integration role, supervisors take steps to facilitate opportunities for student-parents to enhance their parenting skills and strategies. For example, this might entail sharing valuable resources, organising workshops or establishing connections with relevant parenting support networks. Furthermore, supervisors play an active role in advocating for a healthy work-life balance among student-parents, engaging with institutional policies to ensure adequate resources and support are accessible to this demographic. Effective advocacy might mean pushing for family-friendly policies, endorsing flexible work arrangements or facilitating childcare assistance. Beyond academic matters, the balanced-integration role extends its reach to encompass the overall well-being of student-parents. Supervisors are actively involved in ensuring emotional and psychological health, fostering open discussions about stressors, and creating an environment conducive to mitigating challenges. They do not necessarily have to provide this support but must be equipped with the skills and resources to direct students appropriately.

As illustrated in Figures 4 and 5, the observation on funding and study leave validates the ongoing trend within academia wherein individuals benefit from more favourable conditions for pursuing higher education. This insight holds particular relevance for doctoral candidates who are also parents, as it underscores the advantages of the higher education landscape that could aid their journey compared to other sectors. Including this dimension in the model can guide supervisors of student-parents within the higher education sector, offering insights on effectively leveraging available provisions through targeted training on institutional policies and human resource practices.

Contrary to the assumption that challenges faced by student-parents stem from a shortage of parenting resources, this study has found that it is, in fact, inadequate work-related support that is of primary concern. This realisation, particularly within a sector like higher education where funding and leave provisions are prevalent, prompts a reassessment for policy adjustments and institutional interventions. Universities can consider comprehensive support structures that address childcare and work-related challenges, including flexible work arrangements and workload redistribution. The absence of support and potential income reductions due to reduced work hours might also impact doctoral student-parents' long-term academic and professional paths, warranting further investigation.

Supervisors as designers of customised academic pathways

Supervisors have an opportunity to collaborate closely with student-parents in crafting comprehensive time management strategies that consider the demands of academia, parenting and employment. By guiding student-parents in prioritising tasks and setting achievable goals, supervisors can empower them to allocate their time effectively between studies, work and family responsibilities. This approach contrasts with instances where literature highlights supervisors expressing frustration toward student-parents struggling to meet academic deadlines because of parenting and work complexities. Embracing this aspect may prompt supervisors to perceive holistic student development as part of their role. Further, in this role, supervisors guide student-parents on effective time management, helping them juggle academic commitments and parenting duties, including creating flexible schedules, setting practical goals and identifying strategies for efficient time allocation.

Supervisors engaging with doctoral students who are both parents and employees need to acknowledge student reliance on informal support networks, as indicated in Figures 4 and 5. Often susceptible to unforeseen changes, these informal sources can significantly impact a student's engagement in doctoral work. For example, students who depend on their child's school schedule might face challenges during school closures. Sensitivity to these challenges can encourage supervisors to incorporate clauses within Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) that recognise potential disruptions. This gesture demonstrates empathy and highlights often overlooked aspects of the doctoral journey, recognising the importance of supervision that, while focused on the end goal, is flexible enough to take a different route with each student to support each unique journey best.

The notable issue with the workload, highlighted in Figures 14 and 16, is respondents' perceptions that they lack adequate time for essential tasks, leading to unreasonable work demands. While MoUs might not directly address this issue, this is a challenge that students must confront externally, often with their employers. Here, supervisors can play a role by communicating on the student's behalf requesting adjustments to the workload to accommodate dual responsibilities. Particularly in higher education, where provisions for workload relief exist, supervisors can advocate for students who are parents to access these measures.

This encourages supervisors to consider interventions like peer support networks and engagement with institutional wellness resources as part of the MoU. Just as supervisors would direct students to an academic resource to bridge a research gap, they should also be prepared to guide students toward wellness resources when emotional distress arises. While supervisors might not be the direct providers of this support, proper training in making appropriate referrals is crucial.

Supervisors as catalysts for family-inspired motivation

Survey findings revealed a notable trend: most respondents (73%) completed or were on track to complete their doctoral studies within four years. This contrasts with the common notion of doctoral students who are also parents often taking longer to finish their studies due to various challenges. These results suggest that student-parents can achieve their academic goals within a reasonable timeframe despite obstacles. While no direct correlation was established, this achievement might stem from their strong motivation to serve as role models and inspire their children. Supervisors can leverage this powerful motivator by supporting students in their academic challenges aligning their parental roles with their pursuit of education. The balanced-integration role recognises that for parent-doctoral students, obtaining their degree goes beyond their personal achievement and serves as a motivation for their children. Supervisors can actively nurture discussions, reinforcing that academic success is a shared endeavour. By doing so, they can reinforce how learning is contagious, fostering a culture of learning and education within their families.

Analysis of respondents' reflections on the rewards of simultaneously being doctoral students and parents highlights a compelling narrative where personal success, family ties, and educational aspirations intertwine. A recurring theme emerges the satisfaction of effectively managing academics, parenting and work. In this narrative, earning a doctorate qualification symbolises resilience and determination. The concept of being a role model and challenging societal norms offers supervisors a chance to nurture and amplify this transformative influence. By recognising and discussing the positive effects that academic pursuits have on students' families, supervisors can emphasise that their achievements extend beyond academia. This acknowledgement empowers students to embrace their role-model status, fuelling their dedication to studies and fostering a culture of ambition and learning within their families.

LESSONS

A one-size-fits-all approach to supervising doctoral students is insufficient in light of the transformed demographic of postgraduate students. Therefore, supervisors must be flexible and proactive in addressing the unique challenges presented by this demographic shift. This research highlights the importance of designing customised academic pathways for student-parents: there is a need for supervisors to collaborate closely with these students, guiding them in effective time management and goal setting to accommodate the demands of academia, parenting and employment.

Another vital lesson is acknowledging and supporting the reliance of student-parents on informal networks. Understanding the impact of these networks on a student's doctoral journey highlights the need for supervisors to be flexible in agreements and recognise potential disruptions that may arise from changes in informal support structures. The family can also be leveraged as a source of motivation for this group of students.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the shifting landscape of doctoral education worldwide, including in South Africa, demands a correspondingly evolved approach to supervision. The traditional archetype of a doctoral student has given way to a diverse demographic that includes parents and professionals. As explored throughout this article, the challenges faced by student-parents who are also employed while pursuing doctoral studies are multifaceted, encompassing academic, family and career dimensions. The proposed supervisory framework, enriched by including the balanced-integration role, addresses these challenges holistically and offers valuable strategies to support student-parents effectively.

The findings discussed in this article underscore the role of supervisors as advocates for holistic well-being. Supervisors should foster a supportive environment that promotes overall well-being by actively acknowledging the demands of parenting, employment and academia. Embracing the role of holistic well-being advocates allows supervisors to guide student-parents in navigating their multiple roles and challenges, contributing to their development as well-rounded individuals. Furthermore, supervisor engagement in designing customised academic pathways empowers student-parents to manage their time and responsibilities effectively. This dimension recognises the need for tailored approaches that accommodate complexities arising from balancing academic pursuits with parenting and employment. Through flexibility, personalised planning and supportive measures, supervisors can help student-parents traverse their doctoral journey with confidence. Finally, supervisors can act as catalysts for family-inspired motivation, recognising the transformative impact of academic success on student-parents and their families. Acknowledging the intergenerational influence of educational achievement can be a powerful motivational tool. In embracing this role, supervisors encourage a culture of learning and aspiration within families, underscoring the far-reaching significance of academic endeavours.

RECOMMENDATIONS

It is recommended that higher education institutions offer supervisor training programmes that include holistic support strategies. Flexible policies accommodating extended timelines, flexible work arrangements and enhanced wellness resources would better serve student-parents. Promoting successful student-parent role models, interdisciplinary collaboration and inclusivity in family structures would create an environment conducive to student-parent success. Furthermore, from a research design perspective, longitudinal studies are recommended to explore a comprehensive understanding of the evolving challenges of student-parents over an extended period. Incorporating supervisors' perspectives through qualitative interviews could also enrich our understanding of support strategies from both sides of the supervisory relationship.

LIMITATIONS

Several limitations must be acknowledged in this study. Firstly, the research design employed a descriptive quantitative approach through online surveys, which might limit the depth of understanding and nuances of participant experiences. The self-reported nature of the data could introduce response bias and social desirability effects, potentially impacting the accuracy of the gathered information. Additionally, the sample size of 47 respondents from 13 South African higher education institutions and eight institutions abroad might not fully represent the diverse range of experiences and challenges faced by all student-parents pursuing doctoral studies in various contexts. The study's cross-sectional nature also limits the ability to establish causal relationships or track changes over time. Finally, the study focused primarily on student-parent perspectives, and while it highlighted the importance of supervisory roles, it did not delve into supervisors' viewpoints or experiences. However, despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into student-parent challenges in pursuing doctoral degrees. It establishes a foundation for future research and continued discussions on effective supervisory practices in this evolving educational landscape.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to the Council on Higher Education (CHE) for the financial support related to this study. I also wish to acknowledge the Stellenbosch University's Centre for Research on Evaluation, Science and Technology's (CREST) Training Course for Supervisors of Doctoral Candidates at African Universities where this study was initially conceptualised.

REFERENCES

Academy of Science of South Africa. 2010. The PhD Study: An evidenced-based study on how to meet the demands for high level skills in an emerging economy. Consensus Report, Academy of Science of South Africa. https://www.assaf.org.za/files/2010/11/40696-Boldesign-PHD-small.pdf. (Accessed 2 November 2022). [ Links ]

Alabi, Oluwatobi Joseph, Mariam Seedat-Khan, and Ali Arazeem Abdullahi. 2019. "The lived experiences of postgraduate female students at the University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa." Heliyon 5(11): 1-7. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02731. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

Andrewartha, Lisa, Elizabeth Knight, Andrea Simpson, and Hannah Beattie. 2023. "Balancing the books: How we can better support students who are parents." Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 45(2): 160-173. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2023.2180164. (Accessed 28 November 2023). [ Links ]

Borders, L. DiAnne. 1994. "The good supervisor." ERIC 1-2. https://www.counseling.org/Resources/Library/ERIC%20Digests/94-18.pdf. (Accessed 2 November 2022). [ Links ]

Brooks, Rachel. 2013. "Negotiating time and space for study: Student-parents and familial relationships." Sociology 47(3): 443-459. doi:10.1177/0038038512448565. (Accessed 28 November 2023). [ Links ]

Crawford, Kerry F. and Leah C. Windsor. 2021. The PhD Parenthood Trap: Caught Between Work and Family in Academia. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. [ Links ]

Crispin, Laura M. and Dimitrios Nikolaou. 2019. "Balancing college and kids: Estimating time allocation differences for college students with and without children." Monthly Lab. Rev: 1-35. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/bls_mlr/bls_mlr_201902.pdf. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

France-Kelly, Abilasha Aparajithan. 2022. Diaper bags and doctorates: A phenomenological case study of doctoral student parents at a research university. PhD Thesis, Iowa City: University of Iowa. https://iro.uiowa.edu/view/pdfCoverPage?instCode=01IOWA_INST&filePid=13853941090002771&download=true. (Accessed 11 November 2023). [ Links ]

Gill, Paul and Philip Burnard. 2008. "The student-supervisor relationship in the PhD/Doctoral process." British Journal of Nursing 17(10): 668-671. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paul-Gill-4/publication/5293713_The_student-supervisor_relationship_in_the_PhDDoctoral_process/links/0912f508e97e6ae2f9000000/The-student-supervisor-relationship-in-the-PhD-Doctoral-process.pdf. (Accessed 2 November 2022). [ Links ]

Herman, Chaya. 2011. "Obstacles to success-doctoral student attrition in South Africa." Perspectives in Education 29(1): 40-52. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/pie/article/view/76973/67446. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

Lee, Anne. 2019. Successful research supervision: Advising students doing research. Routledge. [ Links ]

Leitch, Andrew, Stephanie Burton, Isaac Ntshoe, Andrew Kaniki, and Ralebipi-Simela. Rockey. 2022. National Review of South African Doctoral Qualifications. Council on Higher Education. https://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/inline-files/CHE%20Doctoral%20Degrees%20National%20Reporte.pdf. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

Lutter, Mark and Martin Schröder. 2020. "Is there a motherhood penalty in academia? The gendered effect of children on academic publications in German sociology." European Sociological Review 36(3): 442-459. doi:10.1093/esr/jcz063. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

Mainhard, Tim, Roeland Van Der Rijst, Jan Van Tartwijk, and Theo Wubbels Wubbles. 2009. "A model for the supervisor-doctoral student relationship." Higher education 58(3): 359-373. doi:10.1007/s10734-009-9199-8. (Accessed 26 October 2022). [ Links ]

Manze, Meredith, Dana Watnick, Lauren Rauh, and Polly Smith-Faust. 2022. "The Expectation of Student Parents to Self-Advocate: The ones who are successful are the ones who keep asking." Community College Journal of Research and Practice: 1 -17. [ Links ]

McAlpine, Lynn, Isabelle Skakni, and Kirsi Pyhaltö. 2022. "PhD experience (and progress) is more than work: Life-work relations and reducing exhaustion (and cynicism)." Studies in Higher Education 47(2): 352-366. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1744128. (Accessed 15 August 2023). [ Links ]

Moors, Amy C., Abigail J. Steward, and Janet E. Malley. 2022. "Gendered Impact of Caregiving Responsibilities on Tenure Track Faculty Parents' Professional Lives." Sex Roles 87(9-10): 498514. doi:10.1007/s11199-022-01324-y. (Accessed 15 August 2023). [ Links ]

Moreau, Marie-Pierre and Charlotte Kerner. 2015. "Care in academia: An exploration of student parents' experiences." British Journal of Sociology of Education 36(2): 215-233. doi:10.1080/01425692.2013.814533. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

Morgan, Allison C., Samuel F. Way, Michael J. D. Hoefer, Daniel B. Larremore, Mirta Galesic, and Aaron Clauset. 2021. "The unequal impact of parenthood in academia." Science Advances 7(9). doi:10.1126/sciadv.abd1996. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

National Planning Commission: Republic of South Africa. 2012. "National Development Plan 2030: Our Future-make it Work." https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/ndp-2030-our-future-make-it-workr.pdf. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

Pearson, Margot and Carole Kayrooz. 2004. "Enabling critical reflection on research supervisory practice." International Journal for Academic Development 9(1): 99-116. doi:10.1080/1360144042000296107. (Accessed 15 August 2023). [ Links ]

Springer, Kristen W., Brenda K. Parker, and Catherine Leviten-Reid. 2009. "Making space for graduate student parents: Practice and politics." Journal of Family Issues 30(4): 435-457. doi:10.1177/0192513X08329293. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

Walker, Melanie and Pat Thomson. 2010. The Routledge doctoral supervisor's companion: Supporting effective research in education and the social sciences. Routledge. [ Links ]

Webber, Louise and Harriet Dismore. 2021. "Mothers and higher education: Balancing time, study and space." Journal of Further and Higher Education 45(6): 803-817. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2020.1820458. (Accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]