Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.37 n.4 Stellenbosch Sep. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/37-4-5318

GENERAL ARTICLES

Postgraduate supervision support in open distance and e-learning: supervisors' and key stakeholders' views

M. T. GumboI; V. G. GasaII

IDepartment of Science and Technology Education, University of South Africa Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6760-4341

IIDepartment of Educational Foundations, University of South Africa Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3402-4268

ABSTRACT

This descriptive case study explores the support that supervisors in the College of Education (CEDU) at the University of South Africa (UNISA) give to Ethiopian doctoral students. It is important to inquire into supervisors' views about the support that they give to students as part of their supervision especially in the open distance and e-learning (ODeL) higher education context. Twelve supervisors who are or have supervised Ethiopian doctoral students were selected by convenience sampling and interviewed individually to gather their views about the support they give (or have given) to their students. Supervisors' views were augmented by other key stakeholders' views to deepen the understanding of support. The findings reveal that supervisors, though faced with unique challenges, made efforts to support students emotionally, academically, and by being the extended hand of UNISA when students could not access certain services or resources. Doctoral students who are faced with contextual challenges can succeed if they are given proper support which is motivated by mutual respect between the supervisor and student. The study can also benefit supervisors in African universities to reflect on the support that they give to their students, especially in the situations that are posed by the students' circumstances.

Keywords: student support, doctoral students, supervisors, supervision, open distance and e-learning

INTRODUCTION

Universities should support students in such a way that they can cope with various academic demands, meet academic expectations, and complete their studies successfully (Netanda, Mamabolo, and Themane 2019). According to Lessing and Schulze (2004), student support can ensure the development of foundational skills required for students' doctoral success. This study aims to explore the support that College of Education (CEDU) supervisors at the University of South Africa (UNISA) give to Ethiopian doctoral students. It is important to explore this phenomenon as it is one of the key aspects of the UNISA-MSHE (Ethiopian Ministry of Science and Higher Education) partnership. The focus of the study is on doctoral student support in the Ethiopian context. The study is however relevant for the international audience as student support is an important service in Open Distance and E-learning (ODeL) institutions, which implicates student attrition, throughput, and success. Also, support for doctoral students is crucial in the higher education sector (Albion and Erwee 2011; Council on Higher Education 2013).

Student support is about the university's effort to help students to complete their studies (Kelly and Mills 2007); it includes course and design elements, instructional support services, and support services (Stewart et al. 2013). In this article, student support refers to the support given by supervisors, backed by available resources in the ODeL institution, to postgraduate students so that they can complete their studies. The article focuses on the academic, emotional, and institutional (structural) support given to Ethiopian students as understood from the supervisor's views but augmented with other stakeholders' views as well - Ministry of Science and Higher Education (MoSHE) Official, three UNISA-Ethiopia Centre officials and students. MoSHE offers support to the students such as paying for their fees; UNISA-Ethiopia Centre is an extension of UNISA that is closer to the students to offer support such as guidance with the registration; students' voices about the support received are critical. These stakeholders' views are important in this case study so to enhance the understanding of the phenomenon.

This study was motivated by a decade-long UNISA-MSHE partnership the aim of which is to train postgraduate students, thus contributing to the educational development in Ethiopia. The authors of this article are part of a team of supervisors who have traveled to Ethiopia annually since 2011 to conduct research workshops as part of the support given to doctoral students. Our direct involvement with students presented us with the opportunity to observe issues related to the supervision support that students receive, language challenges in terms of students' local language versus English as a teaching-learning language; resources in the UNISA Ethiopia library; and issues of connectivity. Our decision to investigate supervision support was informed by our realisation that supervisors are faced with challenges to supervise students in this context, especially from an ODeL perspective. We were also struck by the fact that some supervisors thrive to give support to students even when faced with challenging circumstances. We, therefore, wanted to understand postgraduate student support from the supervisors' point of view and within this highly specific context plus other stakeholders' views surrounding it. Hence, the following research questions were addressed:

• How do CEDU supervisors, including other stakeholders, describe student support in an ODeL context?

• How do these supervisors provide support to Ethiopian doctoral students as part of their supervision?

The next section discusses and motivates the postgraduate supervision and support framework (PSSF) chosen for the study followed by the literature review on various kinds of support. This is followed by a discussion and motivation of research methods. The findings of the study are presented and discussed ultimately.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Lee and Murray's (2013) PSSF helped us to understand the support that supervisors give to Ethiopian students. PSSF has five critical tenets which include functionality, enculturation, critical thinking, emancipation, and quality relationship. Functionality refers to helping students to progress rationally through the research tasks given the challenges that they face in research and thesis writing related to doctoral studies (Lee and Murray 2013; Ekpoh 2016). According to Ekpoh (2016, 67), "research and thesis writing are critical components of postgraduate studies". These tasks can be performed by the students who demonstrate a rigorous rationalisation that a doctoral study demands from them, i.e., to critically engage with the literature and use complex methodological approaches to contribute to the existing body of knowledge (Lee and Murray 2013). Hence, student support and guidance are critical (Lessing and Schulze 2003; Ekpoh 2016) for Ethiopian doctoral students to be able to perform these tasks so that they can fulfill the requirements of a doctoral qualification. According to Higher Education Qualification Sub-Framework (HEQSF) (Republic of South Africa 2013, 74), a doctoral qualification requires students "to demonstrate a high research capability and to make a significant and original academic contribution at the frontiers of a discipline or field. The work must be of a high quality to satisfy peer review and merit publication."

Enculturation, in the context of this article, means to socialise students into the academic research culture, thus deepening their knowledge as they connect with supervisors and other researchers to arm them with experiences. The students become members of a subject-specialist community in research motivated by role-modeling and internship (Lee and Murray 2013). In this instance, the CEDU supervisors should role-model the expert knowledge of the field and refer students to other experts who can add to their growth into competent scholars. The goal is for students to acquire disciplinary values and norms of their fields which can equip them to be "disciplinary savvy" (Ahmadi et al. 2011).

Engaging students in critical thinking can motivate them to constantly function in an inquiry-based learning mode so that they can analyse their work effectively (Lee and Murray 2013). A doctoral study requires students to critically review other scholars' work (Republic of South Africa 2013). The support given to the Ethiopian students by supervisors can therefore make them sharply critical, reflect on their work and reframe their thoughts. Emancipation refers to support in the sense of empowering students in their specialisation fields so that they can perceive the world through those fields' lenses and accumulated experiences (Grant and Hackney 2014). The educational developmental mission of UNISA to Ethiopia can be realised through the empowering role of supervisors to doctoral students who (students) can grow into formidable scholars and develop their country in turn. The ideals of PSSF about student support will culminate in quality supervisor-student and institution-student relationships (Grant and Hackney 2014). Ethiopian students will be motivated in their studies when supervisors are accessible and supportive. UNISA, only represented by UNISA-Ethiopia Centre (UEC) in Addis Ababa, can be brought closer to students through supportive supervisors - that way students will have a positive image of UNISA.

LITERATURE REVIEW

This section reviews the literature related to postgraduate student support with an emphasis on the ODeL context. The reviewed literature draws largely from the ideas of Van Rensburg, Meyers and Roets (2016) which focus on academic support, writing support, emotional support and structural or institutional support. These kinds of support are critical for student success, hence the need for the current study to contribute knowledge about the support that supervisors give to Ethiopian students. In terms of academic support, the supervisor moves with the student through the knowledge- and skills-based process as it becomes relevant. According to Hemmati and Mahdie (2020, 187), an academic learning environment significantly shapes students' learning experience, and the scholarly identity construction, which socialise them into the academic culture. From a postgraduate programme perspective, the supervisor supports the students to develop the competence required for researching a field of study so that they can move toward a deeper understanding of research (Van Rensburg et al. 2016). The students' inherent characteristics (motivation, intelligence, interest, aptitude) can be honed through supportive supervision so that they can realise this development (Van Rensburg et al. 2016).

Students are also supervised within a particular social context to learn how to research. In UNISA's social context, students are guided by academic values, attitudes, and practices, e.g., supervision is guided by the Procedures for Master's and Doctoral Degrees (UNISA 2018) which, among other things, requires students to engage in research independently. Students should thus acquire new understandings of knowledge, behaviours, and practices related to knowledge construction and their roles as researchers (Van Rensburg et al. 2016). However, supervisors' support is needed to enable students to operate within this social context despite differences in context, language, and culture which they may realise in students. The CEDU supervisors should, therefore, implement UNISA's supervision policies while they consider the contextual dynamics revealed in and through students.

Within the ODeL context, postgraduate supervision is characterised by a geographical distance between students and supervisors (Manyike 2017). This makes this study critical, i.e., to understand the supervision of Ethiopian students as provided by an ODeL institution. Therefore, supervisors should understand students' needs so that they can plan the way forward to assist them (Manyike 2017) and establish a rapport with them (Manathunga 2012) to ensure quality working relationships. The supervisor has a critical role to play in providing a supportive, constructive, and engaged supervision process for the development of future researchers with the correct education and skills mix (Van Rensburg et al. 2016). Reguero et al. (2017) claim that the doctoral supervisor is the face of the university and that the parties accountable in this process comprise the student, the supervisor, and the institution. These three components motivated the participation of other stakeholders in this study. In light of this, we opine that the support that Ethiopian students expect from their supervisors is critical within the UNISA-MoSHE partnership. This, however, does not suggest that supervision of students from other contexts is unimportant.

Supervisors should be able to move through the learning processes with their students (Van Rensburg et al. 2016) until graduation. The ideal supervisor should display flexibility and resourcefulness as a personal guide for doctoral students and provide opportunities for their professional development and relevant networks. Implied in this statement are the students' cultures towards which the supervisor should be flexible (Byars-Winston et al. 2018) which makes this study needful - how do South Africa-based supervisors respond to the needs of Ethiopian students who exhibit different cultural traits? Ethiopian postgraduate students exhibit the cultural traits of respect and patriarchy - related to the above question, how do female supervisors handle the supervision of male students, for instance? Understanding and embracing the students' cultures can help supervisors engage the principles of Ubuntu (humanness, care, sympathy, empathy, forgiveness, etc), the heartbeat of the African way of life that impacts every aspect of people's well-being (Letseka 2011; Lefa 2015). In this sense, supervisors will guide the students within a supportive relationship in terms of intellectualism, strategy, and emotion (Van Rensburg et al. 2016).

"The ability to write according to the conventions and forms of disciplinary academic writing is essential to success at university" (Schulze and Lemmer 2017, 54). Writing support involves academic writing that may cover the ability to synthesise and think conceptually, engage in conceptual mapping, debate approaches and content, structure writing, and so forth (Van Rensburg et al. 2016). The expectation is that the supervisor should identify the strengths and weaknesses of the student's writing through the feedback and assessment that the supervisor gives. That is why giving feedback and assessing students' work is very important in their development. Guiding the student through feedback in ODeL helps bridge the distance between the supervisor and student, hence, students will view feedback in their work as critical. In providing feedback and assessing students' work, supervisors may notice that Ethiopian postgraduate students struggle in writing academically especially since many of them "struggle" with the English language. According to Sime and Latchanna (2016, 586), Ethiopia is a multilingual country, but Amharic is a dominant medium of instruction from primary school. However, the political changes of the 1990s in Ethiopia resulted in educational reforms which caused the country to transition from using Amharic and English as the only medium of teaching to a multi-lingual approach (Sime and Latchanna, 2016). According to Seidel and Moritz (in Sime and Latchanna 2016), currently, 25 local languages are used in primary schools. This suggests that English could be used as well. Since transformation in this regard is a recent phenomenon, students are not yet that "strong" in English. Therefore, supervisors need to be patient with students who still struggle to express themselves in English.

The supervisor-student relationships matter most for students' emotional support; these relationships are influenced by the academic and socio-cultural factors of which the supervisor should be aware (Van Rensburg et al. 2016). Emotional support includes aspects such as mutual respect which the supervisor-student relationships should enjoy (Van Rensburg et al. 2016), openness to explore difficulties, and liberal engagement in dialogue. In this kind of relationship, issues of balance of power, gender, cultural background, expectations, and communication patterns may surface (Van Rensburg et al. 2016), but caring and supportive supervisors will engage these issues in ways that will not hamper the supervisor-student relationships (Van Rensburg et al. 2016). Hence, supervision that is based on the principles of Ubuntu aligns with UNISA's commitment, as stated in its 2015 Strategic Plan: An Agenda for Transformation, to "promote African thought, philosophy, interests, and epistemology" (UNISA 2007, 7). The principle of respect, for example, takes precedence in mainstream Ethiopian culture and is evident in students most of whom are mature adults. This supports the idea of a humanising pedagogy in the supervision relationship which can help students to become academically mature and capable researchers ultimately (Khene 2014).

Structural support is the institution's responsibility to avail resources to support students (Stewart et al. 2013). Supervisors are still implicated to give support by helping students to access the available resources since supervisors are the face of the institution to students (Abiddin, Ismail, and Ismail 2011). For instance, supervisors may alert students about funding opportunities, training courses, networking opportunities, etc. (Abiddin et al. 2011). Supervisors can encourage their students to attend research workshops whenever such are planned in Ethiopia.

Literature shows that supervisors regard support for their students as crucial. In this sense, Ali, Watson and Dhingra (2016) explored the supervision-related expectations of postgraduate students, characteristics of effective student-supervisor relationships, and opinions of students and supervisors about research supervision. This was done by surveying the perceptions of 77 supervisors and 131 students about these aspects. The study revealed supervisors' beliefs, i.e., they (supervisors) should support students to acquire appropriate research skills, work independently, develop confidence and be able to present their work in seminars and conferences. In another study in an ODeL university, Lessing and Schulze (2003) conducted three focus groups with supervisors. In the study, the supervisors shared their views about the support they gave their students and the joys of supervision. However, in their attempts to support students, supervisors were faced with challenges such as poor writing skills, poor work, technical presentation issues, and research methods issues.

Thus far, the reviewed literature shows that student support is a crucial aspect of student supervision.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

The study adopted an interpretive paradigm to seek answers in a naturalistic, real, unobtrusive, and non-controlling real-world situation (Tuli 2010) pertaining to supervisors' support to Ethiopian doctoral students. The interpretive paradigm situated the analysis of data in context and guided their meaning by interpreting the situation from the participants who understood the world from their own perspectives (Goduka 2012). A qualitative descriptive case study enabled participatory, field-based interpretive, multifaceted and emergent (Yin 2003) data collection in natural settings (Shavelson and Towne 2002), i.e., data were collected from supervisors at UNISA and other stakeholders, who included students, MoSHE Official, and UNISA-Ethiopia Centre officials in Addis Ababa. The interview guide included questions about the supervisors' views of postgraduate student support at a distance, experiences in supervising Ethiopian students, strategies to motivate students, and the support mechanisms given to students. These aspects were also central to the interviews conducted with the above stakeholders so as to understand the case (supervisors' support to students) deeper.

Twelve supervisors were conveniently selected from a list of supervisors whose supervision load included Ethiopian students. The supervisors were assigned pseudonyms PS1, PS2, PS2, etc., in which PS stands for postgraduate supervisor and is biographed as in Table 1.

The invitation to participate in the study included the above groups in view of transformation as it pertains to their representation. However, only black and white supervisors acceded to the invitation to participate. All postgraduate supervisors were fluent in English. They consented to participate in the study after we obtained ethical clearance and permission to involve UNISA staff and students. Supervisors were interviewed individually during their free time in their offices between January and October 2018. Appointments were made to conduct individual interviews in Addis Ababa between December 2018 and January 2019 with a MoSHE Official, three UNISA-Ethiopia Centre officials (coded as UECO1, UECO2, and UECO3, where UECO stands for UNISA-Ethiopia Centre Official), and two focus group interviews, one with about twelve completed students (focus group coded as FGCompSts) and another with about fifteen current students (coded as FGCurrSts).

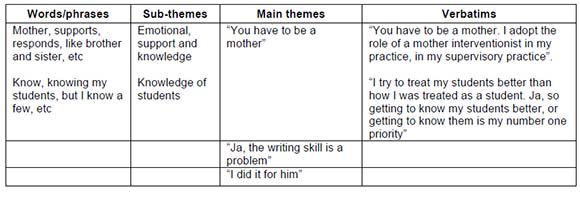

We planned for data analysis and broke data into manageable units, coded and synthesised them as well as traced patterns (Bogdan and Biklen 2003, 298) across data sources. Categorisation helped to compare patterns as we reflected deeply on the complex threads of data while we carefully selected phrases that suited emerging themes. Themes were decided by selecting the appealing/catchy phrases from the participants' verbatims that best represented what each contained. The three themes are "You have to be a mother", "Ja, the writing skill is a problem", and "I did it for him". The following gives an idea about how we practically arrived at the themes in the analysis after coding the data:

Trustworthiness was ensured to provide checks and balances to maintain the acceptable standards of a scientific inquiry (Bowen 2009. It accounted for credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility was ensured through the two years we spent as a team on data collection plus numerous meetings to compare and interpret them. We bracketed our subjectivity to sort out the qualities related to our experience with supervision and support (Drew 2004, 215). To that effect, we made an effort to suspend our presuppositions, biases, assumptions, and theories to accurately describe the participants' life experiences (Chan, Fung, and Chien 2013). We also analysed data through triangulation across data sources. While the findings of qualitative studies are highly contextual, we cannot rule out the transferability of the findings of this study as they may benefit other contexts about the support of other students who are based in other contexts. The study is dependable since the collected information represents the participants' experiences and views, not the researchers' preferences. Regarding confirmability, the findings are narrated and exemplified with the participants' verbatim statements.

FINDINGS

"You have to be a mother"

This theme relates to the emotional support and knowledge of students. The word "mother" in this theme denotes the support like that of a caring parent (mother) and is not gender exclusive, i.e. it includes the male supervisor as well. It is expressed in "you have to be a mother; I adopt the role of a motherly interventionist in my supervisory practice" (PS1); it implicates a caring supervisor (Van Rensburg et al. 2016). This supervisor invested in quality working relationships (Lee and Murray 2013; Van Rensburg et al. 2016; Manathunga 2012): "Ja, so getting to know my students better is my number one priority". She communicated with them from time to time to understand their needs so as to serve them better. PS2 received her students "under-prepared" but they were keen to learn so that they could be empowered through this supervisor's support. This would ensure students' doctoral success (Lessing and Schulze 2004). PS6 and PS9 claimed that they called their students and organised a list of materials to send to them. However, some students did not wait passively but used the library training that they had undergone to search the wealth of resources available at UNISA online (FGCompSts). As stated above, supervisors realised the effects of maintaining quality or healthy supervisor-student working relationships by knowing their students first - it translates into quality support (Lee and Murray 2013). Students can function well when they receive the support that they expect from their supervisors. One student in the FGCompSts stated thus, "I am so lucky, I can say I am so lucky because my supervisor was very, very curious and he was working with me". The FGCurrSts were generally satisfied with the supervision support that they received. Another student from this group appreciated the prompt feedback that he received: "Not weeks, actually within days he gave me my proposal and draft changes, ... then I work with his comments". UECO2 also attested to this support, stating that "students are happy with the services that were provided from College of Education that side".

PS3 had this to say about the students, "some of them do not trust the supervisors ... and that's a challenge because many of them get angry". This supervisor repeatedly mentioned the word "angry" to express students' frustration when supervisors do not respond to their emails. This was an indication of power relations in supervision (Van Rensburg et al. 2016). One student expressed this anger thus, "there was no response given from the supervisor". A few students complained to the UECO1, who stated that "but I know a few, which I might not remember by name or whatever, but I have an experience that people are dissatisfied with supervision". However, PS3 persevered to support students despite those challenges, and described students as responsible and mature adults who were desperate for financial support through bursaries to alleviate the financial demands of the PhD programme - UNISA offers even foreign students bursaries; once the student has completed a research proposal, he/she qualifies to apply for the bursary. A doctoral study has other demands especially when students are far removed from their supervisors (Netanda et al. 2019), especially in a distance learning institution. FGCurrSts were generally faced with personal challenges which prevented them to live up to the demands of the doctoral study, as one student stated, "I'm struggling with working my project and there are also competing priorities in my agenda". Another student elaborately on his situation thus:

"Actually I don't have any challenge with my supervisor. He guides me, he supports me, he responds to my queries very promptly but I have my own personal challenge in terms of - you see - I have a family, I reside in a rented house. I work as contract staff and I don't have enough time to work on my studies and I don't have any communication facilities at home, so these are only my own personal challenges."

Supervisors were motivated by the respect that they received from their students to support them. PS3 attributed this to Ubuntu in the context of the culture of respect as espoused by scholars such as Letseka (2011), Lefa (2015), and Byars-Winston et al. (2018). This alludes to Khene's (2014) attestation about a humanising pedagogy in the supervision relationship. The feeling of respect was also expressed by students, as one of them, whom FGCompSts supported with "yes, yes, yes" stated: "They are so positive, cooperative and very eager you know, to work with individuals, by respecting diversity, by respecting our culture". Most students were advanced in age - viewed as matured adults by supervisors - they (students) described this mutual respect as "working like brother and sister". So, enculturation into Ubuntu as applied in an academic project seemed to be a two-way respect shown by both students and supervisors which spiced quality in their working relationships. So, supervisors also had the opportunity to be adaptable to students' cultures (Byars-Winston 2018).

The supervisor-student relationship is also demonstrated by PS3, "I always send messages to encourage them" such as "hard work pays, ask for family support and explain your study to your family". Timeous feedback to students is critical. PS4 lived up to this expectation as he responded to his student's emails and sent him feedback within two weeks. This demonstrated a "very good working relationship and cooperation" (PS4). PS5 felt that positive comments as part of feedback helped to motivate students. Van Rensburg et al. (2016) support this kind of working relationship. Also, positive and comprehensive feedback in an ODeL environment is critical as it bridges the distance between the "educator" and the student (Manyike 2017) - it gives a feeling of face-to-face interaction. These findings show that supervisors approached their supervision from Ubuntu in the context of UNISA's (2007) transformation agenda. It was however not all "glory" as some students complained about delayed feedback, such as the "no response" expressed above. Added to this concern, "it takes about four, five months to come back again" (expressed from FGCompSts).

"Ja, the writing skill is a problem"

The supervisors identified the students' inability to express themselves in English as a barrier to their academic writing. PS2 stated: "I'm just asking myself if English is the third or fourth or what language to them". Some supervisors were positive about students' self-expression in English, while others had a different take, "... after reading the first paragraph, my head would be reeling" (PS3). PS6 also stated, "You can't even tell what the student is saying". PS4 opined that language constraints impacted students' academic writing, thus hampering their functionality as developing scholars. PS4 also opined that the language barrier tempted students to plagiarise as he related his experience with one student, "... the similarity index was just high; I think 80% or so".

The language issue implicates UNISA's Africanisation of the academic project as part of its transformation agenda in relation to English. However, writing from the Ethiopian context, Sime and Latchanna (2016) argue that the priority given to local languages from the primary school level may disadvantage students' fluency in English. Students need a lot of support so that they can develop their English competence (Sime and Latchanna 2016; Van Rensburg et al. 2016). Hence, supporting students to cope with language challenges would help avoid plagiarism and develop into becoming a more acceptable academic culture (Lee and Murray 2013; Van Rensburg et al. 2016; Hemmati and Mahdie 2020). Given the support that some students received from their supervisors, they were determined to forge ahead with their studies despite these language challenges. A team effort between students and supervisors helped to overcome their challenges as they (supervisors) empowered/emancipated their students into scholars (Lee and Murray 2013) who could even write for publication after completing their studies, as one student from FGCompSt had this to say, "... my supervisor was very helpful. By the way, we produced three articles".

Though supervisors had concerns about the students' English language competence, they continued to support them given their (students') depth of research knowledge and skills. Students also made an effort to implement the knowledge and skills they acquired during the research workshops offered annually in Addis Ababa by a team of supervisors commissioned by CEDU. One student from the completed group commented thus on the support received: "Regarding the academic support, the UNISA professors come to the UNISA Centre in Ethiopia periodically, and give academic support on how to conduct research, methodology, paradigms, research proposal and the like. That helped us a lot". Another student commented thus, "The topics covered in the workshop are quite educational, very well prepared, and I believe that I gained a lot from the workshop presentation that our professors deliver". FGCurrSts also commented positively about the assistance received from the workshops. During the analysis, we learned that UECOs organised extended research seminars for students in which they invited local academics as presenters. The Centre also guided and orientated students about UNISA programmes and registration. "We provide various services ranging from the very beginning when the potential student comes to the Centre" (UECO1).

The supervisors also gave students tips about ensuring language quality in their work so that they could function as expected. Regarding this, PS1 always encouraged students to proofread their work or ask colleagues or peers to do it for them. PS3 advised her students to look for a local competent language editor to edit their work. PS4 guided his students regarding coherence, logical argumentation, completeness of coverage, and formal language. PS1 appreciated that her students were self-driven despite the difficulty that they experienced with English; they followed the guidelines about academic writing. According to PS7, students only lacked language skills, but their scholarly rigour and richness were particularly deep. Many of them teach in Ethiopian universities, hence, they are exposed to the world of academia. They, therefore, show some level of independence (functionality) in their studies instead of being spoon-fed by their supervisors. Thus, some supervisors described students as competent in academic writing. According to Van Rensburg et al. (2016), academic writing is the ability to synthesise and think conceptually, debate approaches and content, structure writing, and so on. This exercise is made possible by students' critical thinking abilities (Lee and Murray 2013). In this regard, PS12 refused to label these Ethiopian students as weak, "No! We cannot say they are weak!" We attest to experiencing Ethiopian doctoral students engaging critically in discussions about their studies both as supervisors and facilitators of research support workshops offered to them annually.

Students' academic writing skills were related to the supervisors' specialisation fields, which was an added advantage to give them support. PS3, PS4, PS7, PS8, PS11, and PS12 employed varied strategies in this regard, such as searching for the literature related to students' topics; sending a courtesy email to ask how they are and how far they are with their work, and ensuring students of their availability; engaging a statistician to help students with methodological challenges; identifying copies of the completed thesis to send to students; downloading audio and visual materials from MyUNISA for students (an online system to offer tutorials and upload materials), sending web links via email for students to access podcasts and video clips on various research aspects.

"I did it for him"

Supervisors supported students by building on what UNISA could offer and stepping in when the online systems failed. For example, PS3 helped his student to resolve the Turnitin issues when the system could not respond. Such supervisors go the extra mile for students so that they can function properly (Lee and Murray 2013; Ekpoh 2016). PS5 stated that "sometimes there's a breakdown in the internet service". Hence, the online systems, exacerbated by delayed feedback from the supervisors, could not function well at times. One student from FGCompSts expressed his frustrations about waiting for about two years to be granted ethical clearance.

One student from FGCurrSts was also disconnected for two months, although the connectivity problem was based on his geographic location. To support this point, both completed and current students experienced connectivity problems not only from the UNISA's side but their context especially because many of them were from places far from Addis Ababa. FGCurrSts stated that they traveled for about 600 km to the research workshops in Addis Ababa. UECOs also confirmed that connectivity was a national problem that had a weak bandwidth, as UECO3 stated, "... to provide any UNISA online resources, it needs a fast bandwidth". According to PS3, some students do not activate their myLife email accounts (email accounts created for students by UNISA). When the online systems fail, PS6 and PS7 resorted to WhatsApp to maintain communication with their students. PS3's desire to meet her students face-to-face "especially when they come to data analysis and interpretation", was rewarded when she was selected to join the team in Ethiopia for the research workshops. She had the opportunity to counter systemic problems. She related her helping the students thus: "I could meet with all my three students to discuss what they wanted to research. So, proposal writing wasn't too difficult for them because we discussed the whole proposal".

The supervisors represented UNISA (Reguero et al. 2017; Abiddin et al. 2011) in extending support to the Ethiopian doctoral students - being an extended hand for the Institution. PS2 and PS4 felt that students should practice academic writing before they can be enrolled in the PhD programme, and that supervisors who have not had the opportunity to go to Ethiopia should be guided by those who have been there about how to supervise Ethiopian students, as they understood the students and their contexts. According to PS4, the academic writing module should incorporate language proficiency to address students' challenges with English. However, PS7 felt that "UNISA has improved a lot in its support for supervisors as far as training to do decent supervising is concerned". This institutional support, which is realised through the supervisors' supportive efforts, could see students completing their studies successfully (Albion and Erwee 2011). PS7 also noted that "UNISA puts in extra support specifically for Ethiopian students, language support and mentors". The institutional support was also echoed by students, who appreciated the wealth of resources, i.e., "electronic journals and books and so many things" which UNISA has to offer through its library. UEC is an extended service to students equipped with library resources including computers for students to search literature from different databases. According to the UECOs, however, students face distance-related challenges as they live far. Also, during national unrest, the internet gets cut off.

Extension of knowledge in the field

Firstly, the study spotlights supervision as support in the postgraduate programme. This has to do with understanding the circumstances of students as a supervisor which are related to their challenges, culture, resources, etc. Making an effort to understand the students can position the supervisor well to supervise them from a support perspective (Gasa and Gumbo 2021). Hence, the support that needs to be given to students in their academic projects should be uncompromised. Secondly, supervision that is anchored on support aligns well with Ubuntu philosophy (Gumbo, Gasa, and Knaus 2022). This notion of support aligns well with "You have to be a mother", which means investing successful supervision in caring about students' needs. Supportive supervision balances working relationships with functionality (Lee and Murray 2013; Ekpoh 2016) that can be achieved through positive supervision-student relationships (Grant and Hackney 2014).

The Biblical saying, "Can the two walk together unless they agree?" (Amos 3:3 NKJV) is most relevant to the implied mutual respect in supportive supervision, which can mitigate the lack of support that some students have expressed in this study. Thus, the findings shed an important insight into the mutual respect that must exist between the supervisor and the student. The culture of Ubuntu exhibited by the Ethiopian postgraduate students situates postgraduate supervision well within Ubuntu - mutual respect signifies a welcoming and supportive gesture by the supervisor and the student. This suggests that supervisors should not only demand work from students but relate well to them so that students can enjoy supervision instead of enduring it. This way, the PhD programme, demanding as it can be, will be completed as supported students can survive its challenges and demands amidst their challenging personal circumstances. Thirdly, the above two points implicate the provision of the postgraduate programme in the African university environment. Care should be taken to ensure that supervisors do not only supervise but that they do so mainly from a support basis. This, however, does not suggest neglect of the other supervision roles such as advice, mentoring, training, teaching, etc. These can be framed well within support - support implicates love and care, hence, "You have to be a mother".

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Our interest in this study was to understand the support given to Ethiopian doctoral students by CEDU supervisors. The views of the supervisors about students supported, augmented by those of other key stakeholders illuminate the understanding that supervisors have about support due to doctoral students; this answers the first research question. The findings also created an understanding of the support that the supervisors provide to Ethiopian students in an ODeL environment, as a response to the second research question. Framed within PSSF, the study shows that with this support, students can be empowered to function within the culture of academia as critical scholars to produce quality work which is expected in a doctoral study. Given the demands of the programme and the situatedness of students, however, it is not always possible for supervisors to have "superstar" students. Despite this, the students' capabilities may not be thwarted by their unfamiliarity with the English language. Supervisors who observe this tirelessly support their students to success despite other related challenges about supervising in an ODeL environment. They did not succumb to the challenges to the point of walking away from their students. Instead, they identified the Ubuntu in the students as the energy that drove the support they gave. Though there could be an element of a patriarchal culture demonstrated by the majority of students being males who have advanced in age, supervisors felt respected irrespective of their gender differences. They also adapted to the culture of respect in the supportive role that they played toward their students. Not all supervisors responded in time or were available, but we argue that the principle of mutual respect would suggest they must be. This study contributes insights into understanding support for doctoral students under challenging circumstances within the ODeL environment. Given proper support which anchors on Ubuntu, students who are faced with contextual challenges can succeed in the doctoral programme. We recommend that:

• CEDU strengthens UNISA-MoSHE partnership by ensuring that supervisors are always available and can respond timeously to students;

• A short orientation session about supervising Ethiopian doctoral students should be conducted so that supervisors can understand their culture and the challenges that they face;

• Supervisors who already have experience in supervising Ethiopian students could be used to give these orientation sessions; and

• Co-supervision should be considered wherein experienced supervisors can mentor inexperienced supervisors (including those identified in Ethiopia) into supervising Ethiopian students.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by UNISA through ODL-RSP grant.

REFERENCES

Abiddin, N. Z., A. Ismail, and A. Ismail. 2011. "The effective supervisory approach in enhancing postgraduate research studies." International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 1(2): 206-217. [ Links ]

Ahmadi, P., A. A. Samad, R. Baki, and N. Noordin. 2011. "Disciplinary enculturation of doctoral students through non-formal education." Paper Presented at the International Conference on Culture, Languages and Literature. Malaysia, Asia. [ Links ]

Albion, P. and R. Erwee. 2011. "Preparing for doctoral supervision at a distance: Lessons from experience." Paper presented at the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference. Nashville, USA. [ Links ]

Ali, P. A., R. Watson, and K. Dhingra. 2016. "Postgraduate students' and their supervisors' attitudes towards supervision." International Journal of Doctoral Studies 11: 227-241. https://doi.org/10.28945/3541. [ Links ]

Bogdan, R. C. and S. K. Biklen. 2003. Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods. Boston: Pearson. [ Links ]

Bowen, G. A. 2009. "Document analysis as a qualitative research method." Qualitative Research Journal 9(2): 27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027. [ Links ]

Byars-Winston, A., V. Y. Womack, A. R. Butz, S. C. Quinn, E. Utzerath, C. L. Saetermoe, and S. Thomas. 2018. "Pilot study on an intervention to increase cultural awareness in research mentoring: Implications for diversifying the scientific workforce." Journal of Clinical Translational Science 2(2): 86-94. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2018.25. [ Links ]

Chan, Z. C., Y. Fung, and W. Chien. 2013. "Bracketing in phenomenology: Only undertaken in the data collection and analysis process." The Qualitative Report 18(30): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2013.1486. [ Links ]

Council on Higher Education. 2013. The Higher Education Qualification Sub-Framework. Pretoria: Council on Higher Education. [ Links ]

Drew, N. 2004. "Creating a synthesis of intentionality: The role of the bracketing facilitator." Advances in Nursing Science 27(3): 215-23. [ Links ]

Ekpoh, U. I. 2016. "Postgraduate studies: Challenges of research and thesis writing." Journal of Educational and Social Research 6(3): 67-74. https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr.2016.v6n3p67. [ Links ]

Gasa, V. G. and M. T. Gumbo. 2021. "Supervisory support for Ethiopian doctoral students enrolled in an Open and Distance Learning institution." International Journal of Doctoral Studies 16(37): 47-69. [ Links ]

Goduka, N. 2012. "From positivism to indigenous science: A reflection on world views, paradigms and philosophical assumptions." Africa Insight 41(4): 123-138. [ Links ]

Grant, K. and R. Hackney. 2014. "Postgraduate research supervision: An 'agreed' conceptual view of good practice through derived metaphors." International Journal of Doctoral Studies 9: 43-60. https://doi.org/10.28945/1952. [ Links ]

Gumbo, M. T., V. Gasa, and C. B. Knaus. 2022. "Centring African knowledges to decolonise higher education." In Decolonising African higher education: Cultivating healing across the continent, ed. C. B. Knaus, T. Mino, and J. Seroto. Milton Park: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hemmati, R. and A. Mahdie. 2020. "Iranian PhD students' experiences of their learning environment and scholarly condition: A grounded theory study." Studies in Higher Education 45(1): 187-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1576164. [ Links ]

Kelly, P. and R. Mills. 2007. "The ethical dimensions of learner support." Open learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning 22(2): 149-157. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680510701306699. [ Links ]

Khene, C. P. 2014. "Supporting a humanizing pedagogy in the supervision relationship and process: A reflection in a developing country." International Journal of Doctoral Studies 9: 73-83. [ Links ]

Lee, A. and R. Murray. 2013. "Supervising writing: Helping postgraduate students develop as researchers." Innovations in Educational and Technical International 52(5): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.866329. [ Links ]

Lefa, B. 2015. The African philosophy of ubuntu in South African education. www.researchgate.net/publication/274374017_The_African_Philosophy_of_Ubuntu_in_South_African_Education. (Accessed 26 April 26 2020). [ Links ]

Lessing, A. C. and S. Schulze. 2003. "Lecturers' experience of postgraduate supervision in a distance education context." South African Journal of Higher Education 17(2): 159-168. [ Links ]

Lessing, N. and A. C. Schulze. 2004. "The supervision of dissertations and theses." Acta Comercii 4: 73-87. [ Links ]

Letseka, M. 2011. "Educating for ubuntu." Open Journal of Philosophy 3(2): 337-344. [ Links ]

Manathunga, C. 2012. "Supervisors watching supervisors: The deconstructive possibilities and tensions of team supervision." Australian Universities' Review 54(1): 29-37. [ Links ]

Manyike, T. V. 2017. "Postgraduate supervision at an open distance e-learning institution in South Africa." South African Journal of Higher Education 37(2): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n2a1354. [ Links ]

Netanda, R. S., J. Mamabolo, and M. Themane. 2019. "Do or die: Student support intervention for the survival of distance education institutions in a competitive higher education system." Studies in Higher Education 44(2): 397-414. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1378632. [ Links ]

Reguero, M., J. J. Carvajal, M. E. García, and M. Valverde. (Ed.). 2017. Good practices in doctoral supervision: Reflection from the Tarragona Think Tank. Tarragona: Universitat Rovirai Virgili. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. 2013. "Publication of the General and Further Education and Training Qualifications Sub-Framework and Higher Education Qualifications Sub-Framework of the National Qualifications Framework." Government Gazette No. 36797. Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Schulze, S. and E. Lemmer. 2017. "Supporting the development of postgraduate academic writing skills in South African universities." Per Linguam 33(1): 54-66. https://doi.org/10.5785/33-1-702. [ Links ]

Shavelson, R. J. and L. Towne. (Ed.) 2002. Scientific research in education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [ Links ]

Sime, T. and G. Latchanna. 2016. "Place of diversity in the current Ethiopian education and training policy: Analysis of Cardinal dimensions." Educational Research and Reviews 11(8): 582-588. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2015.2614. [ Links ]

Stewart, B. L., C. E. Goodson, S. L. Miertschin, M. L. Norwood, and S. Ezell. 2013. "Online student support services: A case-based on quality frameworks." Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 9(2): 290-302. [ Links ]

Tuli, F. 2010. "The basis of the distinction between qualitative and quantitative research in social science: Reflection on ontological, epistemological and methodological perspectives." Ethiopian Journal of Education and Sciences of Jimma University 6(1): 97-108. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejesc.v6i1.65384. [ Links ]

UNISA. 2007. 2015 Strategic Plan: An Agenda for Transformation. Pretoria: UNISA Press. [ Links ]

UNISA. 2018. Procedures for Master's and Doctoral Degrees. Pretoria: UNISA Press. [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, G. H., P. Meyers, and L. Roets. 2016. "Supervision of post-graduate students in higher education." Trends in Nursing 3(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.14804/3-1-55. [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. 2003. Case study research: Design and methods. 3rd Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]