Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Higher Education

versão On-line ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.37 no.2 Stellenbosch Mai. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/37-2-5025

GENERAL ARTICLES

The correlation between materialism, social comparison and status consumption among students

T. PelserI; P. J. van SchalkwykII; J. H. van SchalkwykIII

IToyota Wessels Institute for Manufacturing Studies Durban, South Africa, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5935-0185

IINorth-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. School of Management Sciences, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6800-4978

IIINorth-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. School of Management Sciences, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8887-9715

ABSTRACT

South African students face many challenges when completing their tertiary education, finances being one of the most significant. This is not only due to a lack of monetary resources but also to students' inability to manage their available resources. Students often make financial decisions not in their own interest due to both internal and external factors. Consequently, many students do not finish their studies or end up in debt.

The research reported on in this article examined the correlation between three factors which influence spending and debt according to previous research, namely Materialism, Social Comparison and Status Consumption. These concepts refer to how much people value material possessions and how they compare their possessions to those of others and spend on status-conferring possessions to improve their image.

This study used convenience sampling of 630 Generation Y students registered from four university campuses. Data collection was conducted using a self-reporting questionnaire. Data analysis comprised 597 valid questionnaires. The results reveal that Status Consumption can be predicted using Materialism and Social Comparison tendencies.

The net result of this situation is that students first compare themselves to their peers and then spend money to feel better about themselves or present an improved image to their peers instead of investing their limited resources in their education. Very often, this spending is funded using credit. According to existing literature, this is true for students and the population at large and is one of the main drivers of the current debt problems South Africa is experiencing.

Keywords: materialism, social comparison, status consumption, financial resources, student finances, students.

INTRODUCTION

Student protests, often violent and even deadly, have become an annual occurrence in South Africa. Most of the protests are centred on the demand for free tertiary education and the administration of the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) (Isilow 2021; Matebesi 2021).

Although students have many legitimate complaints, there have also been allegations that students are not using NSFAS funds for educational purposes only and that they are even selling university-subsidised laptops (Mlamla 2019; Van Rensburg 2020). The problem, therefore, does not only lie in the limited resources available but also how the resources are allocated and used. This necessitated investigating what drives students to spend and consume products they often cannot afford.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

Economic researchers have assumed that consumers make rational decisions to maximise utility and generate wealth (Finn 1992). This ignores that subjective considerations such as status also play a role in consumer behaviour (Kim and Jang 2013). These considerations often lead consumers to make prestige purchases that they cannot afford and are not in their best interest (Ordabayeva and Chandon 2010; Chipp, Kleyn, and Manzi 2011).

Almost 25 million South Africans were credit-active in 2017, and 70 per cent of middle-class consumers were in financial distress. This is in part because the number of credit-active South Africans exceeds the total number of people employed by eight million (Ferreira 2017; News24 2017). Furthermore, research by Momentum (2021) found that South African households' overall Financial Wellness score declined by 3.5 points, from 68.7 points in 2018 to 65.2 points in 2020.

The Covid-19 lockdown and the detrimental effects this has had on the economy have further exacerbated the situation. The middle class were particularly hard-hit, and many relied on credit to survive (News24 2021a). The number of people seeking help with debt has also increased by 31 per cent from 2020 to 2021, and many people are spending half of their income on servicing debt (News24 2021b). Many consumers became trapped in a situation where they needed to take on new debt to repay existing loans while paying interest on all their obligations. This leads many people to become over-indebted and leads to further consumer debt (Stoop, 2009).

Debt levels are equally high or higher among South African students, who often spend more than the average South African while dependent on parents and NSFAS for income (Masilela 2020). This may, in part, be because Generation Y, of which current students form part, is an expressive and image-conscious generation and reportedly spends more money on clothing, 40 per cent of their income and on electronics, 20 per cent of their income (Cronje, Jacobs, and Retief 2016).

Previous research claims that Materialism, Social Comparison and Status Consumption are related constructs (Cronje et al. 2016; Ordabayeva and Chandon 2010), leading to higher spending and often higher debt (Sandhu 2015; Donnelly, Ksendzova, and Howell 2013; Chipp et al. 2011). This study combines variables from earlier studies to show how Materialism and Social Comparison lead to Status Consumption among South African students, which may lead to higher student debt.

CONCEPTUAL AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The conceptual framework of this study is based on previous research that found that not only are Materialism, Social Comparison, and Status Consumption related, but Materialism and Social Comparison may lead to increased Status Consumption and increased consumer debt. Previous research found evidence that all three factors independently lead consumers to spend more money, even if it causes them to become over-indebted.

Materialism is the first factor relevant to this research, defined as "the importance a consumer attaches to worldly possessions" (Belk 1984). Materialism is mostly perceived to be a negative trait because of the supposed connection between happiness and material possessions (Segal and Podoshen 2013). Furthermore, previous studies have found a negative relationship between actual well-being and Materialism (Deckop, Jurkiewicz, and Giacalone 2010; Burroughs and Rindfleisch 2002; Kasser and Ryan 1993). This may be due to individuals who are more materialistic making judgements based on material possessions, which in turn may lead to lower life satisfaction (Tsang et al. 2014; Segal and Podoshen 2013). Recent studies have found a statistically significant link between advertisements and Materialism and also a strong positive correlation between Materialism and marketing. This may indicate that external influences can be more important than family influence in individual Materialism (Davila, Casabayó, and Singh 2017; Sandhu 2015).

Materialism tends to be higher in developing countries. Duh (2014) found that youth in South Africa were more materialistic than those in developed countries. People who grow up feeling disadvantaged or from a lower socioeconomic status often escape feelings of inadequacy by embracing Materialism (Kim et al. 2017). Khare (2014) found that more materialistic individuals tend to overspend more often, even if they had to borrow money.

As Materialism is such an important variable in predicting debt use, Materialism may be contributing to South Africans' indebtedness (Ponchio and Aranha 2008). This is supported by Donnelly et al. (2013), who found that more materialistic people tend not to manage their credit well and make purchases for emotional reasons, such as believing that purchases will transform or improve their lives.

Furthermore, instead of managing their money to maximise buying power, Materialism motivates people to spend more, borrow, and save less. Furthermore, credit card overuse occurs more frequently among people who view borrowing in a more favourable light. Thus, while materialistic individuals are more concerned about finances, that does not translate into better financial decisions (Rootman and Antoni, 2015; Hogarth 2002).

The next factor to consider is Social Comparison which is the "tendency to compare one's status to that of others in determining whether or not one has enough" (Norvilitis and Mao 2013). Festinger (1954) theorised that people evaluate their opinions and abilities by comparing themselves to their peers. He called this phenomenon Social Comparison. More recent research has revealed that people also compare behaviour, values, possessions and appearance (Tiggemann et al. 2018).

When people compare themselves to their peers, it can be unfavourable (upward) or favourable (downward) comparisons (Ordabayeva and Chandon 2010). Upward comparisons occur faster and can produce feelings of envy and inferiority. This may cause consumers to buy and display the same possessions, which positively associates Upward Social Comparisons with materialistic aspirations (Kim et al. 2017; Chan and Prendergast 2007).

Social media provides near unlimited and instantaneous opportunities for Social Comparison, and the number of "likes" a post receives on social media can be used measure for comparisons. However, social media presents an unrealistic ideal for comparison because people try to present a positively skewed image limited to what they want others to see. This often includes images that have been edited and enhanced (Chae 2017).

When people make unfavourable or upward Social Comparisons, the outcome may lead to dissatisfaction, even among objectively well-off people. This may lead to an aspiration trap where consumers constantly have to make larger and more frequent purchases to satisfy their competitive appetite for acquiring new products (Nagpaul and Pang 2017a). Research has found that while people with low self-esteem may use upward comparisons for self-improvement, upward comparisons are more likely to reinforce their dissatisfaction (Tiggemann et al. 2018; Nagpaul and Pang 2017b; Fox and Vendemia 2016).

Narcissistic people are more likely to make downward or favourable comparisons while generating self-promotional content that often misrepresents their lives to maintain their inflated egos (Chae 2017; Fox and Vendemia 2016). Social people tend to post more often, while less social people post less, thus presenting a skewed view of social life (Deri, Davidai, and Gilovich 2017). Social media users present their ideal self instead of their actual self, and therefore social media comparisons are mostly negative and may therefore cause feelings of envy and inadequacy (Ozimek, Bierhoff, and Hanke 2018). This also happens when people compare their situations to determine if they are keeping up with their peers. Such Social Comparisons may trigger competitive status-driven expenditures (Kim and Jang 2017).

Finally, Social Comparison plays a role in normalising debt. Consumers see that their peers are also in debt, which is considered normal (Pattarin and Cosma 2012). All of this may explain why consumers who are more inclined towards Social Comparison also tend to have more debt and lower financial well-being (Norvilitis and Mao 2013)

Status Consumption is "the motivational process by which individuals strive to improve their social standing through the conspicuous consumption of consumer products that confer and symbolise status both for the individual and surrounding significant others" (Eastman, Goldsmith, and Flynn 1999). Veblen (1899) realised that social image may drive consumption and this led to his research into conspicuous consumption, the: "desire of everyone to excel everyone else in the accumulation of goods [where] the end sought by accumulation is to rank high in comparison with the rest of the community in points of pecuniary strength".

Other authors have expanded on the original research and created their definitions. Status Consumption, Conspicuous Consumption and "keeping up with the Joneses" have been used interchangeably to describe the same phenomenon; social standing and image can be improved by displays of wealth (Cronje et al. 2016; Chipp et al. 2011).

Status Consumption can be defined as the "process of gaining status or social prestige from the acquisition and consumption of goods that the individual and significant others perceive to be high in status" and conspicuous consumption "involves expenditures made for purposes of inflating the ego coupled with the ostentatious display of wealth" according to Grotts and Widner-Johnson (2013). Cronje et al. (2016) define Status Consumption as the desire to increase social status through consumption, or consumers communicate social and economic standing to others using prestige goods as status symbols.

While the type and nature of products consumed may differ among different cultural groups, men engage in Status Consumption more often than women (Moav and Neeman 2012; Chipp et al. 2011). Income and possessions determine how others see a person and how they see themselves. Poorer households often spend money on status conferring products even though the higher spending may have dire financial consequences. This effect becomes more pronounced in societies where inequality is higher.

Ordabayeva and Chandon (2010, 27) explain that "consumers at the bottom of the distribution spend a larger proportion of their budget on status-conferring consumption to reduce the dissatisfaction they feel with their current level of possessions due to the widening gap between what they have and what others have". This is also common among individuals with low self-esteem seeking social approval by following the latest trends in fashion and lifestyle (Nga, Yong, and Sellappan 2011).

Furthermore, the media play an important part in marketing a product as a status-conferring product (Goldsmith, Flynn, and Kim 2010). Status and prestige influence consumer behaviour because increasing social status is an important motivator for many consumers (Kim and Jang 2013). Leguizamon (2016) found that middle-class consumers often indulge in status consumption of products aimed at the wealthy to signal high status. Status-driven purchases by both low- and high-income consumers may be motivated by the fear of failure and loss of self-respect. This motivates consumers to maintain a lifestyle to impress their peers, even if they have to incur debt to maintain this lifestyle (Chipp et al. 2011).

Researchers have found a significant negative relationship between cognitive age and Status Consumption (Eastman and Iyer 2012). Younger consumers are much more likely to indulge in status consumption. Furthermore, Generation Y has been socialised in an increasingly materialistic society and associates self-esteem and public self-consciousness with displays of wealth. This motivates Generation Y to consume for status and engage in frivolous spending. This also happens among students who are not financially self-sufficient and rely on parents, NSFAS and bursaries (Butcher, Phau, and Shimul 2017; Kim and Jang 2013).

The high propensity towards status consumption among economically deprived consumers in emerging economies and young people may partly explain why South African students make purchases motivated by status (Cronje et al. 2016).

Therefore, consumers more inclined towards Materialism, Social Comparison, and Status Consumption are more inclined to buy status conferring goods and may often do so using credit (Kim and Jang 2017; Nagpaul and Pang 2017a; Khare 2014; Ordabayeva and Chandon 2010; Chipp et al. 2011).

METHODOLOGY

The research aimed to examine the correlation between three factors influencing spending and debt according to previous research: Materialism, Social Comparison and Status Consumption. These concepts refer to how much people value material possessions, compare their possessions to those of others, and spend on status-conferring possessions to improve their image.

The methodology used in this study was quantitative and revolved around using students as the primary sample source. This target involved Generation Y individuals aged between 18 and 24 at the time who were registered at a Higher Education Institution in South Africa.

The study used non-probability convenience sampling, as requesting a complete sample frame from HEIs was impossible. The study's sample size was 597 after the cleaning process, which involved taking out incomplete questionnaires or showing too many outliers and skewed the data. Outliers were removed as the data was generalised to the population in question.

RESULTS

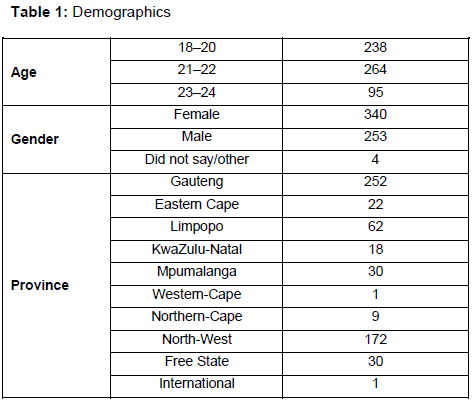

The results from the 597 viable questionnaires are shown below, commencing with an overview of the demographic details of those who responded to the study. Table 1 shows the age, gender, and province of those who responded to the study.

Table 1 shows that the age spread favoured ages 18-22, with the highest percentage of respondents. The reasoning behind this might be that there tend to be more first and second-years than third-years and postgraduates. The majority of respondents were female 340 versus 253 male respondents, which corresponds to the disparity between female and male enrolment in HEIs (DHET 2020). Lastly, most respondents were from Gauteng, followed by North-West Province, which could be explained by the fact that the HEIs used were based in Gauteng and North-West Province.

Considering the demographic makeup of the study, the following could be assumed: This study will hold the most veracity for females or males aged 18-22 who live in Gauteng or North West Province. The next section focuses briefly on the factor analysis conducted for the study. Little detail was added to avoid elongating the study with unnecessary data.

Exploratory factor analysis

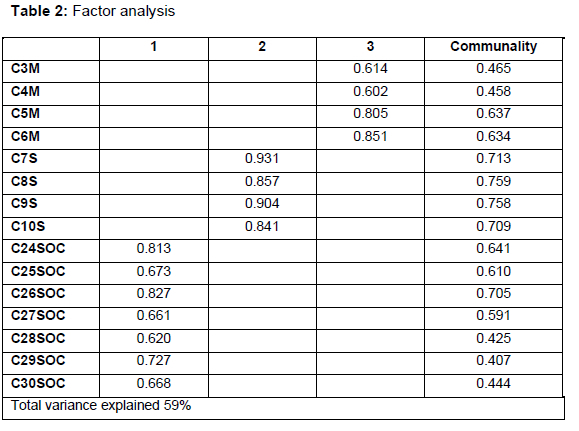

The exploratory factor analysis was run on SPSS using promax rotation. The study used three factors, and a limit was put on the factors extracted. Lastly, values under 0.4 were suppressed to ensure that only higher-quality data was used. Table 2 shows that the three factors used in the study fit together per the study's assumption. Moreover, factor values and commonalities were high enough for the factors to be deemed acceptable.

Table 3 shows the results from the KMO and Bartlett's tests. The KMO showed a value of 0.893, which is sufficient, according to Larose (2006). The Chi-Square value and degrees of freedom were 3788.596 and 105, respectively. The factor analysis showed significance at a 0.000 level.

This study used three factors: Materialism, Status Consumption, and Social Comparison. The items fit perfectly into their respective variables after cleaning the rotation. The cleaning process involved taking out the low-item score and low-communality score items. The items that were taken out were: C2M, C3M and C23SOC. Thus, it can be assumed that each variable is valid and that the items inside them fit as per expectation.

Multicollinearity

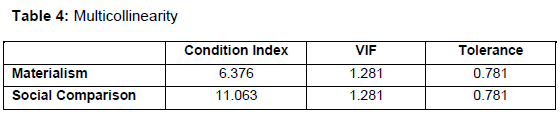

A multicollinearity test (see Table 4) was conducted to determine the Condition Index (CI) and VIF. The CI for the dependent Status Consumption showed a CI, VIF, and Tolerance level within acceptable levels. CI < 30; VIF ~ 10 or less (Hair et al. 2014; Gaskin 2011); Tolerance higher than 0.1 (Orme and Combs-Orme 2009; Su, 2016). Thus, it can be concluded that the multicollinearity test is acceptable. The next section briefly discusses the descriptive statistics used to analyse the data.

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive section of the article analysed the mean, standard deviation, and skewness of the data. A total of 597 questionnaires were used to assess the mean, standard deviation, and skewness. The mean for Materialism shows in Table 5 that respondents were, overall, materialistic in nature (mean = 4.290).

However, for both Status Consumption and Social Comparison, low values were observed. Thus, respondents did not see themselves as buying for status, nor did they see themselves as comparing themselves to others.

Each skewness was within the threshold of -1 to 1 (ISU 2010; Chan 2003). Standard deviation showed that despite there being a low mean statistic for both Status Consumption and Social Comparison, there was a tendency for some respondents to deviate from this, showing that there is a range of opinions on this. Status Consumption, for example, at 2.766 with a standard deviation of 1.302 shows that several respondents had higher inclinations towards Status Consumption and the same for Social Comparison.

Correlation analysis

Pearson's Correlation Analysis in Table 6 shows nomological validity as each variable correlated favourably in the expected direction, showing two-tailed significance. Thus, it can be assumed that with a change, positive or negative, for any of the variables, a corresponding change would occur in its companion variable. This is highlighted by a 0.501 connection between Social Consumption and Social Comparison.

Structural equation model

The structural equation model that was conceived for this study is shown next in Figure 1.

After the removal of CM6, model fit was achieved. The model showed sufficient fit (see Table 7), which shows that the model has sufficient significance and can be used for statistical generalisations.

Moreover, the model showed a sufficient correlation between the independent variables, Materialism and Social Comparison and the dependent variable Social Consumption. Furthermore, the model showed significance for both Social Consumption to Materialism and Social Consumption to Social Comparison.

RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS

Self-administered questionnaires only look at quantitative data based on, in this case, what the respondents felt about themselves. Thus, the veracity of their view on Status Consumption and Social Comparison might be higher or lower in practice.

However, it is telling that the mean statistic for Materialism was high as it speaks to a global phenomenon where consumers want to consume more. This might indicate good marketing practice, increased internet and social media reach, or a testament to increasing prosperity. Regardless, Materialism bodes well for any organisation. Thus, with Materialism at such high levels, it is the onus of the manager and the organisation to implement marketing campaigns that successfully use this.

The study also showed a positive correlation between Materialism, Status Consumption, and Social Comparison, each increasing positively in correspondence. Thus, where highly sought-after products are advertised, appealing to materialistic tendencies, organisations could do well in positioning their products as status symbols or showcasing their products on social media, worn or used by others. This can trigger Social Comparison, which will be higher amid high levels of Materialism.

Moreover, with the advent of the "influencer", Materialism and Social Comparison have entered a new realm of possibility where celebrities and social influencers can be used for marketing purposes. This is a fine line of budget spending as not all products have high sought-after rates or materialistic appeal. However, this study shows the crucial inter-relationship between the three variables and that Status Consumption relies on Materialism and Social Comparison.

Limitations

This study used self-administered questionnaires, which relied entirely on the respondents' opinions regarding their own state of mind. Thus, there could have been personal bias in answering questions. A qualitative analysis of the information through interviews could have shed extra light on the true motivations and opinions of the respondents. The study did not focus on specific brands or categories of products, which means that higher levels of Materialism, Social Comparison, and Status Consumption might have been seen in product-specific or brand-specific categories.

CONCLUSIONS

The study aimed to highlight the importance of the relationship between Status Consumption, Materialism, and Social Comparison. The findings showed that respondents did not find themselves motivated by Status Consumption and Social Comparison but showed strong Materialistic tendencies.

Moreover, the standard deviation showed a variation of opinions regarding this and that many see themselves as consuming for status compared to their peers, family or friends. This is further shown as important in Pearson's Correlation Analysis, which showed a positive two-tailed relationship between each of the variables. This relationship showed the highest in Social Comparison and Status Consumption, which could lead one to surmise that when one is more status-oriented, one tends to compare oneself more to others.

Moreover, a higher level of Materialism compared to Status Consumption and Social Comparison shows that Materialism might be seen as a variable that can sometimes stand on its own merit. That is to say, despite a global tendency towards Materialism, it is not necessarily the case that consumers buy to compete with others in their social groups. However, this is only assumed due to the high mean values of Materialism compared to the other variables.

Finally, the study showed a significant relationship between Materialism, Status Consumption, and Social Comparison. Both Materialism and Social Comparison do influence whether an individual consumes for status. Besides the apparent marketing implications, this research also suggests that there rests an onus on educational institutions better to equip students with the necessary life and financial skills to make prudent financial decisions. Research has found that financial literacy can improve financial inclusion and financial behaviour (Rootman and Antoni 2015, 474; Hogarth 2002, 14), while people who lack financial skills often make harmful financial decisions which may result in higher financial debt (Boon, Yee, and Ting 2011, 151; Sabri, Cook, and Gudmunson 2012, 156). Transformative pedagogy encourages students to examine their assumptions and beliefs about material possessions and social status. Thus, equipping students with the necessary financial skills may help counter the pressure students feel from the media and from peers to spend money on status conferring products and services.

REFERENCES

Belk, R. W. 1984. "Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness." In NA - Advances in Consumer Research, ed. Thomas C. Kinnear and U. T. Provo, 11: 291-297. Association for Consumer Research. [ Links ]

Boon, T. H., H. S. Yee, and H. W. Ting. 2011. "Financial literacy and personal financial planning in Klang Valley, Malaysia." International Journal of Economics and Management 5(1): 149-168. [ Links ]

Burroughs, J. E. and A. Rindfleisch 2002. "Materialism and well-being: A Conflicting values perspective." Journal ofConsumer Research 29(3): 348-370. DOI:10.1086/344429. (Accessed 12 January 2022). [ Links ]

Butcher, L., I. Phau, and A. S. Shimul. 2017. "Uniqueness and status consumption in Generation Y consumers: Does moderation exist?" Marketing Intelligence and Planning 35(5): 673-687. DOI:10.1108/MIP-12-2016-0216. (Accessed 13 January 2022). [ Links ]

Chae, J. 2017. "Virtual makeover: Selfie-taking and social media use increase selfie-editing frequency through Social Comparison." Computers in Human Behavior 66: 370-376. DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.007. (Accessed 23 January 2022). [ Links ]

Chan, Y. H. 2003. "Biostatistics 101: Data presentation". Singapore Medical Journal 44(6): 280-285. [ Links ]

Chan, K. and G. Prendergast. 2007. "Materialism and social comparison among adolescents." Social Behaviour and Personality 35(2): 213-228. DOI:10.2224/sbp.2007.35.2.213. (Accessed 13 January 2022). [ Links ]

Chipp, K., N. Kleyn, and T. Manzi. 2011. "Catch up and keep up: Relative deprivation and conspicuous consumption in an emerging market." Journal of International Consumer Marketing 23(2): 117134. DOI:10.1080/08961530.2011.543053. (Accessed 23 January 2022). [ Links ]

Cronje, A., B. Jacobs, and A. Retief. 2016. "Black urban consumers' status consumption of clothing brands in the emerging South African market." International Journal of Consumer Studies 40(6): 754-764. DOI: 10.1111/ijcs.12293. (Accessed 13 January 2022). [ Links ]

Davila, J. F., M. Casabayó, and J. J. Singh. 2017. "A world beyond family: How external factors impact the level of materialism in children." Journal of Consumer Affairs 51(1): 162-182. DOI: 10.1111/joca.12103. (Accessed 2 February 2022). [ Links ]

Deckop, J. R., C. L. Jurkiewicz, and R. A. Giacalone. 2010. "Effects of materialism on work-related personal well-being." Human Relations 63(6): 1007-1030. DOI:10.1177/001872670935395. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Department of Higher Education and Training. 2020. "Gender fact sheet: For the post school education and training system." https://www.dhet.gov.za/Planning%20Monitoring%20and%20Evaluation%20Coordination/Fact%20Sheet%20on%20Gender%20Parity%20in%20Post-School%20Education%20and%20Training%20Opportunities%20-%20March%202021.pdf (Accessed 11 January 2022). [ Links ]

Deri, S., S. Davidai, and T. Gilovich. 2017. "Home alone: Why people believe others' social lives are richer than their own." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113(6): 858-877. DOI:10.1037/pspa0000105. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

DHET see Department of Higher Education and Training. [ Links ]

Donnelly, G., M. Ksendzova, and R. T. Howell. 2013. "Sadness, identity, and plastic in over-shopping: The interplay of materialism, poor credit management, and emotional buying motives in predicting compulsive buying." Journal of Economic Psychology 39: 113-125. DOI:10.1016/jjoep.2014.11.001. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Duh, H. I. 2014. "Application of the human capital life-course theory to understand Generation Y South Africans' money attitudes." Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies 6(12): 974-985. DOI:10.22610/jebs.v6i12.554. (Accessed 2 February 2022). [ Links ]

Eastman, J. K., R. E. Goldsmith, and L. R. Flynn. 1999. "Status consumption in consumer behaviour: Scale development and validation." Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 7(3): 41-52. DOI:10.1080/10696679.1999.11501839. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Eastman J. K. and R. Iyer. 2012. "The relationship between cognitive age and status consumption." Marketing Management Journal 22(1): 80-96. [ Links ]

Ferreira, K. 2017. "Analysis: How indebted consumers are stretching SA to its limits." https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/economy/2017-09-12-indebted-consumers-on-a-credit-knife-edge/. (Accessed 11 January 2022). [ Links ]

Festinger, L. 1954. "A theory of Social Comparison processes." Human Relations 7(2): 117-140. DOI:10.1177/001872675400700202. (Accessed 29 January 2022). [ Links ]

Finn, D. R. 1992. "The meanings of money - a view from economists." American Behavioural Scientist 35(6): 658-668. DOI: 10.1177/0002764292035006003. (Accessed 17 January 2022). [ Links ]

Fox, J. and M. A. Vendemia. 2016. "Selective self-presentation and social comparison through photographs on social networking sites." Cyberpsychology, Behaviour, and Social Networking 19(10): 593-600. DOI:10.1089/cyber.2016.0248. (Accessed 17 January 2022). [ Links ]

Gaskin, J. 2011. "Detecting multicollinearity in SPSS." https://youtu.be/oPXjQCtyoG0. (Accessed 17 January 2022). [ Links ]

Goldsmith, R. E., L. R. Flynn, and D. Kim. 2010. "Status consumption and price sensitivity." Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 18(4): 323-338. DOI:10.2753/MTP1069-6679180402. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Grotts, A. S. and T. Widner-Johnson. 2013. "Millennial consumers' status consumption of handbags." Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 17(3): 280-293. DOI:10.1108/JFMM-10-2011-0067. (Accessed 1 February 2022). [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, and M.Sarstedt. 2014. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modelling. 1st Edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

Hogarth, J. 2002. "Financial literacy and family and consumer sciences." Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences 94(1): 14-28. [ Links ]

Illinois State University (ISU). 2010. "SPSS: Descriptive Statistics." http://psychology.illinoisstate.edu/jccutti/138web/spss/spss3.html. (Accessed 13 January 2022). [ Links ]

Isilow, H. 2021. "South Africa: Student's protest, demand free education." https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/south-africa-students-protest-demand-free-education/2176560. (Accessed 1 February 2022). [ Links ]

Kasser, T. and R. M. Ryan. 1993. "A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65(2): 410-422. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Khare, A. 2014. "Money attitudes, materialism, and compulsiveness: Scale development and validation." Journal of Global Marketing 27(1): 30-45. DOI:10.1080/08911762.2013.850140. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Kim, D. and S. Jang. 2013. "Motivational drivers for status consumption: A study of Generation Y consumers." International Journal of Hospitality Management 38(1): 39-47. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.12.003. (Accessed 1 February 2022). [ Links ]

Kim, D. and S. Jang. 2017. "Symbolic consumption in upscale cafés: Examining Korean Gen Y consumers' materialism, conformity, conspicuous tendencies, and functional qualities." Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research 41(2): 154-179. DOI:10.1177/1096348014525633. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Kim, H., M. J. Callan, A. I. Gheorghiu, and W. J. Matthews. 2017. "Social comparison, personal relative deprivation, and materialism." British Journal of Social Psychology 56(2): 373-392. DOI: 10.1111/bjso.12176. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Larose, D. T. 2006. Data mining methods and models. 1st Edition. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [ Links ]

Leguizamon, S. 2016. "Who cares about relative status? A quintile approach to consumption of relative house size." Applied Economics Letters 23(5): 307-312. DOI:10.1080/13504851.2015.1066485. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Masilela, F. 2020. "A large number of SA students are in debt and 25% have store cards - here's what they are buying and how to avoid the trap." https://www.news24.com/w24/Work/Money/a-large-number-of-sa-students-are-in-debt-and-25-have-store-cards-heres-what-they-are-buying-and-how-to-avoid-the-trap-20200209. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Matebesi, S. 2021. "The puzzle of student protests: An unresolved battle." https://www.news24.com/news24/columnists/guestcolumn/analysis-the-puzzle-of-student-protests-an-unresolved-battle-20210319. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Mlamla, S. 2019. "Are textbook sales on decline after NSFAS allowed cash pay-outs to students?" https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/are-textbook-sales-on-decline-after-nsfas-allowed-cash-payouts-to-students-19827134. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Moav, O. and Z. Neeman. 2012. "Saving rates and poverty: The role of conspicuous consumption and human capital." Economic Journal 122(563): 933-956. DOI:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2012.02516.x. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Momentum. 2021. "Momentum | Unisa science of success insights report." https://retail.momentum.co.za/documents/campaigns/scienceofsuccess2021/unisa-science-of-success-insights-report.pdf. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Nagpaul, T. and J. S. Pang. 2017a. "Materialism lowers well-being: The mediating role of the need for autonomy - correlational and experimental evidence." Asian Journal of Social Psychology 20(1): 11-21. DOI: 10.1111/ajsp.12159. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Nagpaul, T. and J. S. Pang. 2017b. "Extrinsic and intrinsic contingent self-esteem and materialism: A correlational and experimental investigation." Psychology and Marketing 34(6): 610-622. DOI:10.1002/mar.21009. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

News24. 2017. "Middle class is buckling under debt: Survey." http://www.enca.com/money/middle-class-is-buckling-under-debt-survey. (Accessed 21 January 2022). [ Links ]

News24. 2021a. "A third of South Africa's middle-class set to be wiped out: Lender." https://businesstech.co.za/news/finance/489723/a-third-of-south-africas-middle-class-set-to-be-wiped-out-lender/. (Accessed 12 January 2022). [ Links ]

News24. 2021b. "Struggling middle-class South Africans are spending more than half their salaries to pay off debt." https://businesstech.co.za/news/finance/489723/a-third-of-south-africas-middle-class-set-to-be-wiped-out-lender/. (Accessed 12 January 2022). [ Links ]

Nga, J. K. H., L. H. L. Yong, and R. Sellappan. 2011. "The influence of image consciousness, materialism and compulsive spending on credit card usage intentions among youth." Young Consumers: Insight and Ideas for Responsible Marketers 12(3): 243-253. DOI: 10.1108/17473611111163296. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Norvilitis, J. M. and Y. Mao 2013. "Attitudes towards credit and finances among college students in China and the United States." International Journal of Psychology 48(3): 389-398. DOI:10.1080/00207594.2011.645486. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Ordabayeva, N. and P. Chandon. 2010. "Getting ahead of the Joneses: When equality increases conspicuous consumption among bottom-tier consumers." Journal of Consumer Research 38(1): 27-41. DOI10.1086/658165. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Orme, J. G. and T. Combs-Orme. 2009. Multiple regression with discrete dependent variables. 1st Edition. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Ozimek, P., H-W. Bierhoff, and S. Hanke. 2018. "Do vulnerable narcissists profit more from Facebook use than grandiose narcissists? An examination of narcissistic Facebook use in the light of self-regulation and social comparison theory." Personality and Individual Differences 124: 168-177. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.016. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Pattarin, F. and S. Cosma. 2012. "Psychological determinants of consumer credit: The role of attitudes." Review of Behavioural Finance 4(2): 113-129. DOI:10.1108/19405971211284899. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Ponchio, M. C. and F. Aranha. 2008. "Materialism as a predictor variable of low income consumer behaviour when entering into instalment plan agreements." Journal of Consumer Behaviour 7(1): 21-34. DOI:10.1002/cb.234. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Rootman, C. and X. Antoni. 2015. "Investigating financial literacy to improve financial behaviour among black consumers." Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences 8(2): 474-494. [ Links ]

Sabri, M. F., C. C. Cook, and C. G. Gudmunson. 2012. "Financial well-being of Malaysian college students." Asian Education and Development Studies 1(2): 153-170. [ Links ]

Sandhu, N. 2015. "Persuasive advertising and boost in materialism - impact on quality of life." IUP Journal of Management Research 14(4): 44-60. [ Links ]

Segal, B. and J. S. Podoshen. 2013. "An examination of materialism, conspicuous consumption and gender differences." International Journal of Consumer Studies 37(2): 189-198. DOI:10.1111/j.1470-6431.2012.01099.x. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Stoop, P. N. 2009. "South African consumer credit policy: Measures indirectly aimed at preventing consumer over-indebtedness." South African Mercantile Law Journal 21(3): 365-386. [ Links ]

Tiggemann, M., S. Hayden, Z. Brown, and J. Veldhuis. 2018. "The effect of Instagram 'likes' on women's social comparison and body dissatisfaction." Body Image 26: 90-97. DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.07.002. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Tsang, J., T. P. Carpenter, J. A. Roberts, M. B. Frisch, and R. D. Carlisle. 2014. "Why are materialists less happy? The role of gratitude and need satisfaction in the relationship between Materialism and life satisfaction." Personality and Individual Differences 64(1): 62-66. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2014.02.009. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, E. 2020. "VUT students' pawn and sell university's laptops." https://vaalweekblad.com/66502/vut-students-pawn-and-sell-universitys-laptops/. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]

Veblen, T. 1899. "The theory of the leisure class." New York: Penguin. http://moglen.law.columbia.edu/LCS/theoryleisureclass.pdf. (Accessed 3 February 2022). [ Links ]