Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.37 n.2 Stellenbosch May. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/37-2-5046

GENERAL ARTICLES

An innovative online plagiarism course for students at a South African university

S. MahomedI; I. MackrajII; C. BlewettIII

IUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. School of Laboratory Medicine and Medical Sciences, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7095-9186

IIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. School of Laboratory Medicine and Medical Sciences

IIIUniversity of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. Discipline of Management, IT, and Governance

ABSTRACT

Plagiarism is a major concern across institutions of learning. We developed and implemented an innovative online course to teach students about plagiarism. This study aimed to ascertain why students plagiarise, and to determine whether the course would impact students' knowledge and perceptions of plagiarism. This case study used a mixed-methods approach. The "Understanding Plagiarism" course was based on the principles of the Activated Classroom Teaching model that uses 5 digital-age pedagogies (Curation, Conversation, Correction, Creation, Chaos) to encourage engagement. Data was obtained from surveys administered before and after the course. 148 students accessed the course and 98 completed the surveys. The main reasons identified for committing acts of plagiarism included improved grades, laziness, and unintentional plagiarism. Students' knowledge of plagiarism improved after completing the course (67% to 93%). The majority (83%) agreed that students who plagiarise should be disciplined, and 68 per cent agreed that they felt guilty if they copied from a friend, textbook, or the internet. This research shifts the discourse on plagiarism from policy to programme and in particular the implementation of active pedagogic approaches to online teaching. Two implications of this study are, firstly, active pedagogies need to be adopted to ensure effective learning, and secondly, plagiarism which is increasing should be programmatically, and not punitively addressed.

Exposure to the course on plagiarism improved students' understanding of the seriousness and the types of plagiarism.

Keywords: interactive, academic dishonesty, academic integrity, referencing

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it many challenges and opportunities as teaching, learning, and research shifted online. Along with this shift came an increased awareness of issues, such as plagiarism. While plagiarism and academic integrity are long-standing issues (Aasheim et al. 2012; Masic et al. 2017) driven by competitive research environments, the increased use of online tools and resources has led to an increase in reported cases of plagiarism, both by students and staff (Dinis-Oliveira 2020; Reyneke, Shuttleworth, and Visagie 2021). As the practice of teaching and research evolves, it is imperative to develop strategies to inculcate a culture of integrity in learning and research. Plagiarism refers to

"using someone else's words, ideas, organization, drawings, designs, illustrations, statistical data, computer programs, inventions, or any creative work as if it were new and original to you ... (It also includes) buying or procuring of papers, cutting and pasting from works on the Internet, not using quotation marks around direct quotes, paraphrasing and not citing original works, and it is having someone else write your paper or a substantial part of your paper and turning it in as if it were new and original to you." (Cosma and Joy 2008).

Plagiarism is an academic misdemeanour that may have serious repercussions such as paper retraction for a researcher or a student being suspended. Within the context of globalisation, increased use of online resources, and easy access to vast amounts of information, students may commit acts of plagiarism either intentionally or unintentionally.

One of the common causes of plagiarism reported in research is unintentional plagiarism, where students' lack of understanding of what constitutes plagiarism results in them plagiarising (Elander et al. 2010; Fatemi and Saito 2020). The teaching of ethics relating to plagiarism has been shown to be of benefit to students' understanding of plagiarism (Fatemi and Saito 2020; Martin 2012). However, currently most universities in South Africa do not appear to have a standardised approach to the formal teaching of plagiarism (Mphahlele and McKenna 2018). At the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), there is currently no university-wide approach to teaching about plagiarism. However, students are nonetheless required to agree to and abide by the university's plagiarism policy.

As such, we identified the need to explore the impact a comprehensive and standardised plagiarism training approach would have on students' attitudes to plagiarism. An online training approach was adopted to potentially maximise both accessibility to, and the benefits of the training. While the first iteration was conducted in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the exponential growth in online learning during 2020 further underscored the need for an online approach to this training.

While there has been a massive growth in online teaching and learning over the past few years, there have also been reports of poor completion rates of these online courses by students, with average completion rates below 13 per cent in many online courses (Ardchir et al. 2018).

This is partly attributed to an overall lack of engagement and interactivity (Li et al. 2020). This project sought to leverage the benefits of online learning, such as availability, the need for distance learning, access to experts, and time flexibility (Zygouris-Coe 2019) while also attempting to address the issues related to poor student engagement and completion. To increase completion rates, the course design was based on the ACT (Activated Classroom Teaching) pedagogic model, which applies the pedagogies of Curation, Conversation, Correction, Creation, and Chaos to encourage active engagement in online learning (Blewett 2016).

This study aimed to gain a clearer insight into the reasons students plagiarise and to determine whether an active education intervention would impact students' knowledge and perceptions of plagiarism. As such, this study sought to answer the following critical questions: (i) what are students' attitudes toward, and knowledge and practice of plagiarism? (ii) why do students plagiarise? and (iii) what impact does an active online course have on students' knowledge and perception of plagiarism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Technological design

The conceptual design guiding this research is based on the Technology, Pedagogy, and Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework, which describes a model for effective online teaching based on "three core components: content, pedagogy, and technology, plus the relationships among and between them" (Koehler and Mishra 2009). The course was designed to be delivered online through the institutional Learning Management System (LMS), Moodle. Moodle is currently the most widely used LMS (Capterra 2018), and so, in addition to providing easy access to our students, it can easily be integrated into Moodle platforms at other institutions. An additional consideration that became more significant during the enforced COVID shutdown in 2020, was the zero-rating of access to our institutional domain on mobile networks. This meant that students could continue to learn by accessing the Moodle LMS using mobile phones, and not incur data costs.

Pedagogical design

The vast majority of e-learning implementation strategies, while focusing on technology and content design, typically fail to address the pedagogic element. This failure to include a pedagogical foundation in online courses is largely due to the lack of appropriate cohesive digital pedagogies (Bali 2014). As such, this project sought to underpin the technology and content aspects of the online course with a cohesive set of pedagogies. The Activated Classroom Teaching (ACT) model was used to guide the design of the online content to ensure it maximised student learning engagement (Blewett 2016).

The ACT model includes 5 digital-age pedagogies (Curation, Conversation, Correction, Creation, Chaos) that encourage engagement by leveraging the affordances of technology (see Figure 1). These pedagogies were explicitly designed into the course to encourage active learning and increase course completion rates.

Content design

The online course "Understanding Plagiarism" consisted of 7 modules:

1. Learning Online

2. What is Plagiarism?

3. Types of Plagiarism

4. Understanding Referencing

5. Plagiarism Tools

6. Assessment

7. Pledge and Beyond

The first module (Learning Online) explained to students how to be effective in an online learning course. It is a mistake to assume that simply because students are so-called "digital natives", itself a contested phrase (Selwyn 2009), that they understand how to learn effectively online (Mueller 2017). As such, the first module explained the underpinning ACT pedagogies as a key part of the explicit strategy to make the underpinning pedagogies visible to students.

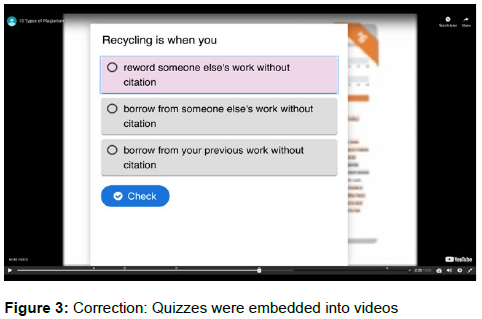

Modules 2 to 5 covered the key learning content around plagiarism. Each module embedded elements of curation (careful reading to find and collect hidden "stash items" - Figure 2), conversation (through discussion forums around topics), correction (multiple choice quizzes and embedded video quizzes - Figure 3), creation (creating notes about learning), and chaos (summarising learning in reflective journals).

While each of the modules had assessments as part of the pedagogy of correction, Module 6 was a summative assessment based on all material. The quiz formats were structured to give students multiple attempts to complete the final assessment.

The final module, "Pledge and Beyond", served two key purposes. The first was to get the students' agreement not to plagiarise. Usually, students are required to sign a declaration form indicating that they will not commit any form of plagiarism without a clear explanation of what this declaration means. This course aimed to develop their understanding of plagiarism and its harm to themselves and others, and after completion of the course, the students take the "Plagiarism Declaration". The declaration was not a legal document but rather a conscious affirmation. The second purpose of the final module was to provide a space for the students (as part of the pedagogy of Chaos) to reflect on their learning and distil their thinking. The "Reflective Journal" was an optional activity that encouraged students to "share anything about your learning journey ... (and) write your thoughts down to bring clarity to your learning".

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

A pilot project was run based on the "Understanding Plagiarism" online course at UKZN in September and October 2019. The pilot consisted of 74 students who were registered for the Bachelor of Medical Science Honours and Bachelor of Commerce (IST) Honours programmes. Results from the pre- and post-course quizzes showed an overall improvement in the students' knowledge of plagiarism. Positive feedback was received on the use of the online environment for learning. The only criticism was that students reported that they would have preferred to have had access to the course earlier in the academic year. Based on the pilot study, minor technical issues were addressed, and the course was then offered to students registering for the aforementioned programmes in 2020.

Three datasets were used from the course. The first dataset was a "Getting to know you" survey that students answered at the beginning of the course. This survey requested basic demographic data (age and gender), the year of study, the college in which the student was registered, whether the student had previously taken a course on plagiarism or any online course and whether the student had read the University Policy on Plagiarism. There were also open-ended questions for the students to indicate what they thought plagiarism entailed, why they thought students plagiarise, and what they hoped to achieve from completing this course. The final component of this survey assessed students' knowledge and attitudes toward plagiarism. A 5-point Likert scale was used to record students' responses to each statement. A value of "5" on the scale indicated strong agreement, and a value of "1" indicated strong disagreement with the statement.

The second dataset was a repeat of the knowledge component of the initial "Getting to Know You" survey, and was administered after the student had completed all modules in the course. This repeat survey included an open-ended section for students to indicate what they felt about the course and provide any comments. The third dataset was an anonymous survey that was administered through Google Forms and delinked from any student identifiers. In this anonymous survey, students were asked about their practice of plagiarism and whether they had ever committed any acts of plagiarism.

The data was exported into Microsoft Excel for analysis. Frequencies and proportions were used to present categorical data. The qualitative data from the "Getting to Know You" survey was analysed thematically. This is one of the most common forms of analysis in qualitative research, capable of emphasizing, pinpointing, examining, and recording themes within data (Vaismoradi and Snelgrove 2019). The qualitative data were analysed using NVIVO version 12. The transcripts from the first dataset were identified numerically, and transcripts from the second dataset were identified alphabetically. Each response was read several times to identify content themes. Data coding continued for each student's response until theme saturation was reached (Alam 2020). After this initial search, patterns and commonalities among the themes were identified and grouped into subthemes.

ETHICS AND PERMISSION

The research was conducted in accordance with the University of KwaZulu-Natal Research Ethics Policy, and BERA's Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BE338/19).

RESULTS

Quantitative data - Profile of students

148 students accessed the course in 2020 and completed the anonymous survey. 95 (60.8%) of these students completed both the "Getting to know You" surveys at the start and end of the course. The mean age of the students was 21.9 years (SD: 1.66). The majority of students were female (n=67, 70.5%). More than two-thirds of the students were registered in the College of Health Sciences, and all students were in their 4th or Honours year. The majority of students had not had any formal learning regarding plagiarism (n=83, 91.6%). Only 30 students (31.6%) indicated that they had read the University Policy on plagiarism, despite being in their fourth year of study.

Students' knowledge on plagiarism

Before commencing with the course, all students agreed that presenting someone else's work when writing constituted plagiarism (Table 1). Before commencing with the course, only 59 (62.1%) students agreed that presenting work they had previously submitted was a form of plagiarism. This proportion increased to 93.7 per cent after the students had completed the course. The number of students who agreed that they had sufficient knowledge to allow them not to plagiarise increased from 67 (70.6%) to 93 (97.9%) after completing the course. Only 16 (16.8%) students agreed that plagiarism refers to copying text and not images, which improved to 17 (17.9%) after completing the course.

Students' attitude toward plagiarism

The majority of students (n=79, 83.2%) agreed that students who plagiarise should be disciplined. Only 20 students (21.1%) felt that short deadlines contributed to plagiarism. Sixty-five students (68.4%) agreed they felt guilty if they copied from a friend, textbook, or the internet.

Students' practice of plagiarism

Of the 148 students who completed the anonymous survey, the majority, 122 (82.4%), reported that they had previously paraphrased a few sentences from a textbook without referencing. Just less than half (n=70, 47.3%) reported that they had previously paraphrased a paragraph from a textbook without referencing the textbook. Similar responses were seen for paraphrasing from a website without referencing, with 127 (85.8%) reporting to have done so with a few sentences, and 80 (54.1%) reporting to have done so for an entire paragraph. A surprisingly high number of students, 30 (20.3%) reported to have either submitted previous work or submitted work that another student wrote.

Qualitative data

The presentation of the qualitative data is divided into three categories, namely; (i) students' perceptions of plagiarism, (ii) students' reasons for plagiarism, and (iii) lessons learned from the course.

Students' perceptions on plagiarism

Plagiarism is theft

Many students reported that they viewed plagiarism as an act of taking another author's work and deceitfully presenting the work as their original piece, without acknowledging or giving credit to the original author. Many students considered plagiarism to be unethical because it is a form of theft. Taking the ideas and words of others and pretending they are one's own, is akin to stealing someone else's intellectual property. Students strongly agreed that handing in someone else's writing as one's own is wrong, and is pure disrespect to the owner.

"Plagiarism is a problem, because other people's ideas and thoughts get stolen or used by other people that claim it is their own idea. Credit is not given to the correct people." (Student 8).

"Plagiarism ... promotes theft as a person takes other people's ideas, work and make them their own without referencing it." (Student 28).

Academic consequences

The theme of academic consequences manifested as a form of penalty for plagiarising. This is not surprising given the legal discourse that surrounds plagiarism. Firstly, based on moral grounds, plagiarism is an act of dishonesty, which can lead to legal action and destroy reputations. Secondly, plagiarism can deny students the opportunity to learn as it can lead to expulsion. A plagiarist makes others doubt their integrity and academic performance, with the following comment from one of the students:

"Plagiarism is a problem, because it damages one's dignity and work ethics when found with the same work as the original writer." (Student 28).

Students who deliberately cheat or engage in deceitful behaviour put themselves at a great risk. It was a surprise to some students to learn that plagiarism is a crime and a serious offence that can get a student excluded from the university if found guilty (Student Uu):

"I learned that plagiarism is a serious offence and that I can get excluded from the university if I'm found guilty. It is a huge offence and can never go unpunished."

Discourages learning

Students reported that plagiarism prevented them from creating their own ideas and opinions on a topic, because the plagiarist duplicates another person's work.

"... Also taking credit for it without actually doing any work becomes a problem, because there are no learning opportunities. The way we learn is by actually doing the work so, by copying someone else's work you cheat yourself of the knowledge you get when you actually do your work." (Student 6).

Plagiarism prevents the expansion of knowledge and tends to place a halt on discovery due to ease of access of information.

"Plagiarism is a problem because it allows one to complete a particular task without learning anything." (Student 16).

Perceptions on why students plagiarise

One hundred-and-four and 80 students completed the open-ended section of the before and after "Getting to know You" surveys, respectively. Based on the students' responses, we categorized the reasons for plagiarism as being intentional or unintentional.

Intentional plagiarism

There are two main reasons for intentional plagiarism, the first is a "positive" driver to get good grades. The other is a "negative" driver, including laziness and a lack of interest.

Good grades: Some students reported a substantial pressure to obtain good grades.

"Some do it because they find the online article interesting and feel like it must not be paraphrased in order to score higher marks." (Student 22).

Many students think it is worth the risk of getting caught if they had the chance of potentially scoring better grades. (Student 36).

Laziness and lack of interest: Some students plagiarise knowingly when they feel they have difficult time constraints often brought about due to poor time management and laziness.

"Students plagiarise because of laziness and procrastination which results in them working under pressure due to time constraints." (Student 43).

"Students plagiarize because they want the easy way out. They want to pass or obtain the marks required and proceed to the next level without putting in the effort (Student 78).

"... because people are lazy and they don't want to think for themselves. it's always easy to just copy someone who has done something and gotten it right." (Student 84).

Another aspect is students' lack of inspiration/interest in a topic. This causes them to search for short cuts to complete the work. One student said that,

"Lack of interest in a particular course or disinterest in the assignment, creates a diversion in mind and empower them to favour copying over than presenting their own skills." (Student 51).

Unintentional plagiarism

Unintentional plagiarism is mainly due to a lack of knowledge and inability to paraphrase and/or reference work. Students reported that it is not easy to write an effective summary or to paraphrase without plagiarising, and end up using numerous quotations in their work. Some of the comments suggest that except for the verbatim copying of text, students were confused as to what actions constitute plagiarism. This is evidenced in the following quotes:

"As much as we are told not to plagiarise many students don't fully understand the concept of plagiarism." (Student 99).

"... because they lack knowledge about plagiarism and what it actually is." (Student 7).

What students learnt from the course

The third aspect explored in the thematic analysis was students' experiences with learning in the online course. Students demonstrated an increased awareness of the nature and seriousness of plagiarism. Where previously their understandings leaned towards plagiarism being about verbatim copying, or copying and pasting from the Internet, they reported that they now understood that ideas could be plagiarised and that the sources of all information, even if it be their own work, should be acknowledged. The following key themes emerged.

Referencing

Students reported that they were now aware of the need to acknowledge the sources of their information. One student stated,

"That referencing is vital, there are online systems to check if you have plagiarised and that there are many ways to conduct a good research." (Student C).

Many students indicated that they had learned how to reference sources. This ability to effectively use (and acknowledge) source material is one of the skills that students have learned with an introduction to software that could assist them.

"I've learnt that I need to reference everything whether a direct quote or if I have paraphrased and it doesn't matter whether I have changed the words and used my own words I still need to reference everything." (Student A).

"Do not write others work as your own. Referencing is very crucial!!!" (Student Zz).

In addition to understanding the need to reference, students also reported now learning how to reference, thereby combining the important aspects of why (motivation) and how (action).

"I have learned how to reference properly. I have found useful tools to help me avoid plagiarism and I understand why plagiarism is bad. I know the possible consequences for plagiarising." (Student W).

Types of plagiarism

Students indicated that they learnt about various types of plagiarism including plagiarising one's own work. "I never knew that one could plagiarize their own work until doing this course." (Student Jj).

DISCUSSION

Plagiarism falls under the umbrella of academic dishonesty (AD) (Ercegovac and Richardson, 2004). This is the first reported study of a novel active online learning course for plagiarism at a university; as well as the first reported knowledge, attitude, and practice survey of plagiarism amongst students at a university in South Africa.

Our findings show that the students gained knowledge of plagiarism from the online course, and enjoyed the learning platform. The activated pedagogic approach resulted in higher levels of engagement and enjoyment, which has been shown to improve both course completion and understanding (Yin and Zhang, 2018).

In particular, the proportion of students who agreed that they had sufficient knowledge to allow them not to plagiarise increased by 27.3 per cent, after completing the course. Our findings further underscore the importance of incorporating the teaching of plagiarism in a formal and standardised manner in the curricula of post-secondary syllabi. There are few such studies in the South African context. A report on Ghanaian undergraduate students' understanding of their institutional AD regulations revealed that, although approximately 92 per cent were aware of these regulations (Saana et al. 2016), only 31 per cent rated their understanding as high, emphasising the need for effective online courses. A two-phase mixed-methods research study conducted in 2013 and 2017, found that in the second phase, plagiarism incidents decreased from 44 per cent to 28 per cent, annually (Mahmoud et al. 2020). Although this study did not investigate the incidence of plagiarism at UKZN, it is envisaged that once students are provided with information regarding what constitutes plagiarism and their institution's policy on plagiarism, they are less likely to commit misdemeanours.

Regarding attitudes towards plagiarism, it is encouraging to note that the majority of the students (n=79, 83.2%) agreed that students who plagiarise should be disciplined. This is reinforced by the self-recognition that sanctions against the act of plagiarism were warranted, since their perceptions included the fact that plagiarism leads to academic consequences. Other notable perceptions included the notion that plagiarism discouraged the expansion of knowledge by the perpetrator, and that it should be considered as "academic theft". These are in alignment with the concept of "deep learning" and have the potential to influence behaviour around learning positively.

Students need to embrace six core skills to promote deep learning, according to "New Pedagogies for Deep Learning" (a global partnership of researchers, families, teachers, school leaders, and policy-makers), which include collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, citizenship, character and communication (Fullan and Langworthy 2013). Hence, the acknowledgement that plagiarism is wrong and should not be practised allows students to be receptive to creative thinking, and is in alignment with "good character" or honesty as espoused by the discourse of deep learning (Marques and Macedo 2016).

Many institutions of learning have surveyed the prevalence of plagiarism and other acts of academic dishonesty in teaching and research amongst postgraduate and undergraduate students across various disciplines. While we do not have actual data on prevalence at our institution as a whole, more than 80 per cent of the students who completed the plagiarism course reported that they have previously paraphrased from a textbook without referencing. This is similar to the levels reported by the University of Pretoria where they found that 80 per cent of the participants surveyed admitted to plagiarising assignments from the internet (Russouw 2005). A study conducted in the USA involving 50,000 students found that 70 per cent of the students reported plagiarising assignments and other forms of cheating (James, Miller, and Wyckoff 2019). At Scandinavian Universities in Stockholm, 10 per cent of the PhD students in health sciences acknowledged that research misconduct, defined as fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism, was common (Hofmann et al. 2020). Our findings, together with these, reinforce the need to tackle AD at all undergraduate and postgraduate levels at universities from a policy perspective, including a cohesive and sustained effort from both students and faculty.

Interestingly, it has been reported that while both external and internal factors influence plagiarism, it is behaviour and teaching factors instead of the web that has a considerable impact on plagiarism (Hofmann et al. 2020). Furthermore, a significant positive correlation exists between external stress, pride, and plagiarism; however, no significant relationship exists between academic skills and plagiarism (Fatima et al. 2019). These factors necessitate a more wholistic approach to stemming acts of plagiarism given the complexity of the drivers that lead to this misdemeanour (Fatima et al. 2019).

This study has some limitations. Not all participants completed the pre- and post-course surveys. It is possible that the knowledge, attitude, and perceptions of these students differed from the respondents included in this study. Due to the anonymity of the Practice of Plagiarism survey, we were unable to assess which students were more likely to engage in plagiarism. Factors influencing individual perceptions vary and are understandably complex, underpinned by cultural, discipline specificity, gender and others. This study did not assess these factors, and was limited to students in their 4th year of study. Postgraduate students were not included in this case study, and their knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of plagiarism may differ from the students in this study.

CONCLUSION

This research has attempted to shift the discourse on plagiarism from a policy-driven approach, which is a common approach, to a pre-emptive programme-based intervention designed to educate students on the various aspects of plagiarism. In addition, the application of the ACT model allowed for active pedagogies to be intentionally designed into the learning experience.

Three important implications arise from the research. The first is that unintentional plagiarism may be more common than expected, attributed to a lack of understanding of what constitutes plagiarism and referencing. Secondly, this study shows that an appropriate innovative online training intervention can positively impact student understanding and perceptions of plagiarism. As online learning becomes the "new normal", active pedagogies need to be adopted to ensure increased engagement and enjoyment in order to improve learning. Thirdly, plagiarism which is increasing, can no longer simply be dealt with punitively but needs to be part of a planned programmatic solution.

Future research could be extended to include greater numbers of students, from a wider cross-section including first year to postgraduate levels. Additionally, follow-up surveys to determine if self-reported changes in perception remain after-the-fact, coupled with evidence of improvement in the incidence of plagiarism could provide valuable insights on the effectiveness of learning.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SM conceptualized the research, obtained funding, was involved in project administration and data analysis, and wrote and reviewed all versions of the manuscript. IM assisted with project administration, data analysis and manuscript writing, and reviewed all versions of the manuscript. CB designed the online course, assisted with data curation and analysis, and assisted with writing and review of all versions of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Aasheim, C. L., P. S. Rutner, L. Li, and S. R. Williams. 2012. "Plagiarism and programming: A survey of student attitudes." Journal of Information Systems Education 23(3): 297-314. [ Links ]

Alam, M. K. 2020. "A systematic qualitative case study: Questions, data collection, NVivo analysis and saturation." Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 16(1): 1-31. [ Links ]

Ardchir, S., M. A. Talhaoui, H. Jihal, and M. Azzouazi. 2018. "Predicting MOOC Dropout Based on Learner's Activity." International Journal of Engineering & Technology 7(4.32): 124-126. [ Links ]

Bali, M. 2014. "MOOC pedagogy: Gleaning good practice from existing MOOCs." Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 10(1): 44. [ Links ]

Blewett, C. 2016. "From traditional pedagogy to digital pedagogy: Paradoxes, affordances, and approaches." In Disrupting Higher Education Curriculum 265-287. Brill Sense. [ Links ]

Capterra. 2018. https://www.capterra.com/infographics/most-popular/learning-management-system-software/. [ Links ]

Cosma, G. and M. Joy. 2008. "Towards a definition of source-code plagiarism." IEEE Transactions on Education 51(2): 195-200. [ Links ]

Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. 2020. "COVID-19 research: Pandemic versus 'paperdemic', integrity, values and risks of the 'speed science'." Forensic Sciences Research 5(2): 174-187. [ Links ]

Elander, J., G. Pittam, J. Lusher, P. Fox, and N. Payne. 2010. "Evaluation of an intervention to help students avoid unintentional plagiarism by improving their authorial identity." Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35(2): 157-171. [ Links ]

Ercegovac, Z. and J. V. Richardson. 2004. "Academic dishonesty, plagiarism included, in the digital age: A literature review." College & Research Libraries 65(4): 301-318. [ Links ]

Fatemi, G. and E. Saito. 2020. "Unintentional plagiarism and academic integrity: The challenges and needs of postgraduate international students in Australia." Journal of Further and Higher Education 44(10): 1305-1319. [ Links ]

Fatima, A., A. Abbas, W. Ming, S. Hosseini, and D. Zhu. 2019. "Internal and external factors of plagiarism: Evidence from Chinese public sector universities." Accountability in Research 26(1): 1-16. [ Links ]

Fullan, M. and M. Langworthy. 2013. Towards a new end: New pedagogies for deep learning. Collaborative Impact, Seattle, Washington, USA. [ Links ]

Hofmann, B., L. Bredahl Jensen, M. B. Eriksen, G. Helgesson, N. Juth, and S. Holm. 2020. "Research Integrity Among PhD Students at the Faculty of Medicine: A Comparison of Three Scandinavian Universities." Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 15(4): 320-329. [ Links ]

James, M. X., G. J. Miller, and T. W. Wyckoff. 2019. "Comprehending the cultural causes of English writing plagiarism in Chinese students at a Western-style university." Journal of Business Ethics 154(3): 631-642. [ Links ]

Jin, Y. and L. J. Zhang. 2018. "The dimensions of foreign language classroom enjoyment and their effect on foreign language achievement." International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24(7): 948-962. [ Links ]

Koehler, M. and P. Mishra. 2009. "What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)?" Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 9(1): 60-70. [ Links ]

Li, X., Y. Yang, S. K. W. Chu, Z. Zainuddin, and Y. Zhang. 2020. "Applying blended synchronous teaching and learning for flexible learning in higher education: An action research study at a university in Hong Kong." Asia Pacific Journal of Education 42(2): 211-227. [ Links ]

Mahmoud, M. A., Z. R. Mahfoud, M.-J. Ho, and J. Shatzer. 2020. "Faculty perceptions of student plagiarism and interventions to tackle it: A multiphase mixed-methods study in Qatar." BMC Medical Education 20(1): 1-7. [ Links ]

Marques, D. N. and A. F. Macedo. 2016. "Perceptions of acceptable conducts by university students." Journal of Optometry 9(3): 166-174. [ Links ]

Martin, D. E. 2012. "Culture and unethical conduct: Understanding the impact of individualism and collectivism on actual plagiarism." Management Learning 43(3): 261-273. [ Links ]

Masic, I., E. Begic, and A. Dobraca. 2017. "Plagiarism Detection by Online Solutions." Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 238: 227-230. [ Links ]

Mphahlele, A. M. M. and S. McKenna. 2018. "Plagiarism in the South African Higher Education System: Discarding a Common-Sense Understanding." In Towards Consistency and Transparency in Academic Integrity, ed Salim Razi, Irene Glendinning, and Tomás Foltýnek, 3141. [ Links ]

Mueller, E. 2017. What Students Don't Know About Technology. Duke Learning Innovation. learninginnovation.duke.edu/blog/2017/11/students-dont-know-technology/. [ Links ]

Reyneke, Y., C. C. Shuttleworth, and R. G. Visagie. 2021. "Pivot to online in a post-COVID-19 world: Critically applying BSCS 5E to enhance plagiarism awareness of accounting students." Accounting Education 30(1): 1-21. [ Links ]

Russouw, R. 2005. "Net closes on university cheats." Saturday Star. http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=13&art_id=vn20050226112531241C573402. (Accessed 15 April 2021. [ Links ])

Saana, S. B. B. M., E. Ablordeppey, N. J. Mensah, and T. K. Karikari. 2016. "Academic dishonesty in higher education: Students' perceptions and involvement in an African institution." BMC Research Notes 9(1): 1-13. [ Links ]

Selwyn, N. 2009. "The digital native-myth and reality." Aslib Proceedings 61(4): 364-379. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530910973776. [ Links ]

Vaismoradi, M. and S. Snelgrove. 2019. "Theme in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis." Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 20(3). [ Links ]

Zygouris-Coe, V. I. 2019. "Benefits and challenges of collaborative learning in online teacher education." In Handbook of research on emerging practices and methods for K-12 online and blended learning, 33-56. IGI Global. [ Links ]