Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Higher Education

versão On-line ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.37 no.2 Stellenbosch Mai. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/37-2-5056

GENERAL ARTICLES

Exploring student teachers' experiences of vulnerability in higher education spaces

S. de Jager

Department of Humanities Education, University of Pretoria, Groenkloof Campus, Pretoria, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5946-2566

ABSTRACT

Recently, scientific interest in higher education students' wellbeing has increased. The highlighted issues include professional development, professional identity, and personal behaviour. The significance of this study relates specifically to supporting students' wellbeing by gaining an understanding of factors contributing to their experiences of vulnerability. Through the arts-informed methodology of Photovoice, which emerges from community-based participatory research, 16 student teachers explored the concept of vulnerability in the context of a higher education institution. The research project required student teachers to take photos of that which represents what they perceive as vulnerability. Student teachers explored their personal, school and campus space with this project. Ultimately, this research speaks to the Sustainable Development Goal of good health and wellbeing, which seeks to promote wellbeing across the individual life span, and ensure healthy lives, as well as the Sustainable Development Goal of quality education, which emphasises the need to improve quality of life and quality teacher training.

Keywords: Photovoice, student teachers, Sustainable Development Goals, vulnerability, wellbeing

INTRODUCTION

University students' mental health has been a public health issue of growing concern in recent years, with an increasing body of empirical evidence suggesting university students are at high risk of mental disorders and psychological distress (Baik, Larcombe, and Brooker 2019, 674). Pre-existing issues in university students' mental health and wellbeing have consequently been augmented by the global COVID-19 pandemic (Morgan and Simmons 2021, 172). Moreover, data from the United Kingdom suggest the number of students declaring a mental health condition on entering higher education has doubled within the last three years (Hawkins 2019). Research from developing countries paints a concerning picture, estimating that "between 12 and 46 percent of university students experience mental health problems" (Auerbach et al. 2018, 2955; Harrer et al. 2019, 1759).

In South Africa, the COVID-19 pandemic may increase learning losses and exacerbate existing inequities among vulnerable students (Eloff 2021, 255). Research has also shown that the number of students who are in need of support for mental health challenges surpasses the resources available at most institutions of higher education. This leads to a significant gap in treatment of mental health challenges among students (Auerbach et al. 2016, 2955). The approach to university students of South Africa's mental health and wellbeing has traditionally been limited to deficit models and individual interventions, with limited development of more systemic approaches and solutions.

This study focused on student teachers who will enter the field of education. These student teachers' mental health and wellbeing may eventually affect wellbeing at their schools' systemic level. Although many of these student teachers enter the teaching profession for altruistic and noble reasons, such as wanting to affect change and better the lives of others, they are often confronted with various factors symptomatic to the school system that leave them feeling disempowered and unmotivated for the profession. This becomes evident when considering the teacher turnover and attrition rate, both internationally and locally (Janik 2015, 1009). Teachers report feeling tension, anxiety, depression, anger and frustration, contributing to their dissatisfaction and disillusionment with the profession. Teachers are also regularly reported to be at greater risk of common mental health challenges compared to those in other professions (Stansfeld et al. 2011, 101; Johnson et al. 2005, 178; Kidger et al. 2009, 919). Reduced teacher wellbeing may be challenging for teachers' long-term mental health (Melchior et al. 2007, 573) and that of their learners in the classroom. This already alarming situation was provoked by the recent COVID-19 pandemic, which has contributed greatly to individuals' psychological stress, anxiety, depression and burnout, leading to a crisis in education (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al. 2021, 3861).

Challenging school environments call for student teachers to be visionaries and problem solvers in societies that require social change. To answer this call, we require student teachers who are self-actualised, and indeed self-transcended adults. To speak to the disillusionment and disempowerment of practice, we need to start with students at the university level and explore their sense of wellbeing.

As stated, specific scientific interest in higher education students' wellbeing has increased in recent years (Henning et al. 2018, 5). The highlighted issues include "professional development, professional identity and personal behaviour, as encountered by relatively young individuals, most of whom left secondary school only recently" (Braidman, Regan, and Humphreys 2018). University students find themselves in distinct situations of transition and this places them in the position of having to develop skills regarding personal responsibility and autonomy, even as they develop their future ability to enter the world of work.

This research study is unique since it explored the phenomenon of student teacher wellbeing by focusing on the construct "vulnerability"; defined in the context of this study as uncertainty, risk and emotional exposure (Brown 2015, 50). The main line of enquiry of this research focused on definitions of the term "vulnerability" based on students' experiences. The research also explored how these terms relate to students' personal transformation experiences and how this process informs their perceptions of their profession.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Within the context of this article, the term "vulnerability" was explored as a concept that forms part of self-transcendence within the field of wellbeing.

Understanding of the term "wellbeing" in this study is rooted in the school of Positive Psychology, where wellbeing is situated in the hedonic tradition, which highlights constructs such as happiness, satisfaction with life, positive affect and low negative affect. Other influential approaches regard wellbeing as requiring both hedonic and eudaimonic components; that is, a combination of feeling good and functioning well. Although many approaches to wellbeing exists, they all seem to agree that well-being is multi-dimensional (Huppert and So 2013).

Within the hedonic tradition the term wellbeing is closely related to terms such as happiness (Pollard and Lee 2003) and flourishing (Keyes and Haidt 2003). Keyes definition of flourishing involves "the presence of hedonic symptoms and positive functioning". Flourishing is characterized by high levels of mental well-being, and it epitomises mental health (Huppert and So 2013). Seligman's theory holds that wellbeing involves five distinct components which includes positive emotions (hedonic feelings of happiness); Engagement (feeling engaged and absorbed in life and having positive psychological connections); Meaning (feeling connected to something greater than oneself and having a sense of purpose); and Accomplishment (progressing towards a goal and achieving mastery in life). These five dimensions configure the acronym PERMA (Seligman 2011). Seligman distinguished between wellbeing and flourish by listing his criteria for flourishing as "being in the upper range of positive emotion, engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and positive accomplishment" (Hone et al. 2014, 70). Keyes and Simoes (2012) places wellbeing and flourishing on a spectrum of experiences through the Mental Health Continuum. This model differentiates between three levels of mental health or well-being, namely flourishing (which refers to high levels of well-being), languishing (an indication of lowered levels of well-being), and moderate mental health regarded as in between. In this study the terms wellbeing and flourishing is regarded as closely related, being distinguished only by range of experience. Within the context of education, the term wellbeing as defined by the PERMA model, as well as the term flourishing seems relevant, as both relates to the spectrum of students experiences.

Self-transcendence has been explored within the fields of nursing theory (Smith and Liehr 2018) and psychology (Frankl 1985; Maslow 1971), and refers to "the capacity to expand self-boundaries in a variety of ways" (Smith and Liehr, 2018) Some of these include intrapersonally (toward greater awareness of one's philosophy, dreams, and values), interpersonally (to relate to one's own environment and those of others), temporally (to assimilate one's past and future in a way that is meaningful for the present), and transpersonally (to connect with dimensions beyond the typically discernible world). Self-transcendence can be regarded as "a characteristic of developmental maturity and wellbeing that includes an enhanced awareness of the environment and individuals' orientation towards broadened perspectives of life" (Reed 2009, 397).

Maslow (1971) describes "self-transcendence" as that which brings the individual "peak experiences" in which "they transcend their personal concerns and see from a higher perspective". These experiences often create strong positive emotions like peace, joy, and a "well-developed sense of awareness" (Messerly 2017). Frankl (1985) conceptualises self-transcendence as a primary spiritual motivation that stems from an individual's spiritual nature; it seeks to express itself through an individual striving towards something greater than themselves.

The term "vulnerability" also refers to the experience of difficult circumstances or being confronted with one's mortality. Ito and Bligh (2016, 66) define it as "a subjective perception of uncertainty, risk, and insecurity". For this research, the definition subscribed to is Brown's (2015, 50), stating that vulnerability entails uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure.

Reed (2008, 105) explored the intersectionality of the terms "self-transcendence", "wellbeing" and "vulnerability" as a model of self-transcendence. Three relationships are present in this model, as demonstrated in Figure 1. Evidently, self-transcendence functions as a mediator of wellbeing. Research regarding this model also seems to indicate that self-transcendence mediates the relationship between vulnerability and wellbeing, including mediation of the effects of vulnerability on wellbeing. The significance of this relationship lies in the reasoning that self-transcendence, then, may be an underlying process that explicates how wellbeing is possible in trying or severe situations one may endure (Reed 2008, 105). Self-transcendence, vulnerability and wellbeing thus converge when individuals "find meaning in life's vulnerabilities, expand their boundaries, and connect with themselves, their spiritual dimensions, and others" (Reed 2008, 105). This mature form of growth draw a parallel with and contributes to wellbeing. Self-transcendence is the mediator which converts people's vulnerable experience into wellbeing (Hoshi 2008).

BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY

This article presents a subsection of a broader student wellbeing study that explored the wellbeing of students in the faculty of education at a large, urban university in the Gauteng province of South Africa. The article reports on students enrolled in the postgraduate certificate in education programme in the education faculty.

METHODOLOGY

A qualitative, arts-informed framework was applied to explore and understand how students at the education faculty experience vulnerability. What differentiates arts-informed research is the various creative ways of representing lived experiences and the different depictive mediums of expression that can efficiently enhance the understanding of the human condition and experience (Capous-Desyllas and Bromfield 2018, 1).

The study made use of Photovoice as a data collection strategy. Photovoice, which emerges from community-based participatory research, is a flexible method implemented with groups that are culturally diverse to explore and address community needs (Hergenrather et al. 2009, 686; Moletsane et al. 2007, 20). As a research methodology, Photovoice gave participants a chance to photograph that which they perceived as addressing a relevant concern and present them in a group discussion format. These discussions created space for reflection and discussion of strengths, creating critical dialogue, and reflecting of personal issues. It further developed a forum to present their lived experiences and priorities through self-identified images, language, and context. In the context of this study, Photovoice was chosen for its ability to not only to engage pre-service teachers in analysing issues that affect their lives, but also for its imperative element of "having fun" and using a familiar online platform (Moletsane et al. 2007, 20).

The project required students to take photos representing what they perceived as vulnerability. Students were encouraged to explore their personal space, school space and campus space. This article focuses on discussing the data from the first phase of the research project, which asked students to share the photos that represent vulnerability to them. They were further asked to rank these photos from most to least vulnerable and write a reflection about each photo. In this article, attention is drawn to the photos that students ranked as most vulnerable.

The researcher approached a group of students in a postgraduate programme on campus after one of their lectures. Students were briefed on the research and asked to volunteer if they wanted to take part in the project. Those who volunteered were then contacted via email and invited to a group session where further instructions were given. Students were asked to explore the concept of vulnerability and how they experience this concept through photos. Those who participated all confirmed that they were in possession of a smartphone with camera capabilities. They were asked to take as many photos as they wanted, capturing their experiences of this concept. Participating students then had to sort through these photos and identify three photos to share with the researcher. Students also wrote detailed reflections on each photo and shared these with the researcher; responses were captured via email. Follow-up questions were related to the responses that participants gave and kept to a minimum. However, the length of reflections were not restricted in any way. Participants could choose to respond at-length or concisely.

The photos and reflections on each photo were analysed by the researcher. Datasets were categorised and coded to be integrated and thematically organised. Connotation and denotation were applied as methods of interpretation when analysing the photos, followed by open coding. To ensure systematic data management and analysis, the researcher used computer-based data analysis tools. The study therefore generated two datasets: one on the photos and another on the students' reflections on the photos.

The study was conducted at a large urban university in South Africa during the first semester of 2020. The recruitment and information session was conducted during the day when regular lectures were in progress. Sixteen students volunteered to take photos and reflect on these in their own time over a period of two weeks.

PARTICIPANTS

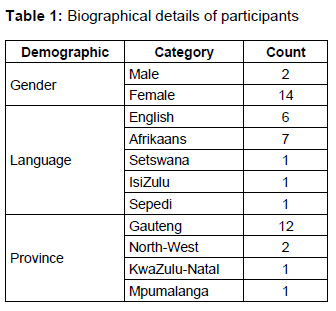

All the participants were student teachers in a postgraduate programme in the education faculty of a large urban university at the time of data collection. Participants were aged between 22 and 31, with the average age being 24. Table 1 shows the counts for other demographic aspects. The sample mainly comprised women living in Gauteng who spoke either English or Afrikaans.

Participation was entirely voluntary in this study. As described earlier, students received an overview of the project and were invited to participate by taking photos of their experiences using their phones. Students had the choice to withdraw at any point during data collection. Students were also provided with the option to withdraw their contributions within a week after their participation.

DATA ANALYSIS

Datasets were categorised and coded to be integrated and thematically organised. Connotation and denotation were applied as methods of interpretation when analysing the photos, followed by open coding. The researcher used computer-based tools to ensure systematic data management and analysis. The study therefore generated two datasets: one on the photos and another on students' reflections on the photos.

The idea behind denotation is that there is a direct and singular relationship of evidence "between signifier and meaning" (Radnofsky 1996, 385); in other words that which is literal and primary. The concept of connotation or metaphor relates to an indirect relationship where "the signifier stands for a concept that, in turn, stands for another concept" (Radnofsky 1996, 385). The methods of denotation and connotation allows for the interpretation of a phenomenon of which the complexity cannot be understood through only textual interpretation alone. This study applied an inductive category procedure (Morgan and Hoffman 2018, 1); it avoided the use of preconceived categories and allowed codes that formed these categories, and descriptions for these categories, to emanate from the data.

Both datasets are presented here in a semi-narrative format for the purpose of creating a nuanced understanding of student teachers' experiences of vulnerability. The study foregrounds individual interpretations of vulnerability, but then weaves a narrative of vulnerability collectively and how this relates to wellbeing.

FINDINGS

An enriching and emotionally rewarding experience was ensured through the use of photovoice as a data collection method for the researcher and the participants. The capturing of images contributed to this experience and the student's visual narratives illustrate the strength of the photovoice process in illuminating the concept of vulnerability. Both the participants and researcher further familiarised themselves with innovative approaches in relating to qualitative inquiry in a mutually respectful and meaningful way (Lenette and Boddy 2013, 72). Through the use of a visual methods the students were able to relate more meaningfully to the concept of vulnerability, leading to greater reflexivity and rich data.

The following four identified themes emerged from the data applying Photovoice methodology to explore vulnerability.

Being confronted with yourself

Participants revealed that they often felt vulnerable when confronted with themselves. Participant G related the following in his reflection:

"This image depicts ... that I find my grotesqueness beautiful and this is corroborated by people around me, but it takes vulnerability to show your dark and ugly sides ... it is learning to love these things we hide from others by showing it to the people we love that help us to develop a self-worth that is not based on accolades and achievements (which are fickle) but true love for the whole self that can transcend hardship" (Participant G).

Another participant shared her experience as follows: "Exposed, raw, no make-up anymore, it's me, I'm here" (Participant J).

Another reflection from a participant included: "This is difficult since I have to face my biggest fear and completely expose parts of me that I have tried to hide, even from myself" (Participant P).

Participant P shared a photo showing the inside of a psychologist's office. The image is dark, and the participant titled the image "The dark room". This image illustrates the process of facing the truth of oneself and personal growth; a process that the majority of participants in the study related to as a source of vulnerability.

Another image denotes a work of art that includes a young boy with a malformed face and worms coming out of his head. In the image, his mother looks at him lovingly. The title of this photo is "mother's little monster"; it depicts a confrontation with the self and an acknowledgement of those parts of the self that scare us the most.

An image shared by Participant J illustrates the self, stripped down to its true form, and depicts a young woman. The photo is titled "Exposed", and the participant related to this image as a self-portrait. The image explores the negotiation of identity and self-acceptance.

The need for connection

The second theme identified from the data was that students felt the need for connection. Student reflections revealed a sense of vulnerability due to a need to be seen and heard. Reflections in this regard included: "No matter that I have been doing this for a while, I still feel vulnerable putting my hand up, and giving my opinion for everyone to see" (Participant H).

Participant C shared a photo titled "The unseen". This image depicts an informal shelter outside the parking area of a university campus. The contrast between the informal shelter in the foreground and a modern university building with luxury cars in the parking area is striking. The participant connected the image to not being able to relate your identity with the university space, and feeling unseen since you do not recognise yourself in anything around you.

This view was confirmed by Participant A, who said: "I am alone looking out to the wild." (Participant A).

Another participant shared a photo titled "Alone", of her sitting and crying while looking at a piece of paper. The image relays a feeling of being overwhelmed and alone. The image further depicts the student holding her hand in front of her mouth, which comes across as an act of silencing herself.

Participant H shared an image titled "Silence" of a piece of paper with the phrase "Asking a question, giving an opinion in class ..." written on it. The student stated that she felt vulnerable in class. She was afraid to share her opinions and ideas due to the fear of being ridiculed or branded. She disliked the version of herself that did not speak up.

Uncertainty of the direction in which their lives are going

Participants related through their reflections and photos that they often felt vulnerable when thinking about the direction in which their lives are going, and whether they are on the right path. Various submitted photos illustrated images or metaphors of a path or journey, often telling a story of a mainstream and an alternative path.

Participant D shared a photo taken from her car during the early morning on a main road in Pretoria. The image titled "Adventure" relates to her journey in life and the programme in which she is enrolled. The path has various exits, which leaves her with a choice of where to go. However, she is also confronted with the vulnerability of not knowing whether the path she chooses is the right one. Participant F shared her experience of uncertainty in the following reflection:

"I realized how uncertain I am about my degree choice. I started questioning if I could really do this and if it would be worth it in the end. I felt like I should just give up and just be." (Participant F).

The photo Participant F is reflecting on is an image titled "Thepath"; it depicts a cement path next to a grass field, both leading to the same parking lot. There are two different paths represented here; one seems more safe and structured, and the other appears to be off the beaten track and more unstructured.

Participant L also shared a photo titled "Wound", containing the image of pink clouds in the early morning. The student reflected that these clouds remind him of an open wound, which to him represents uncertainty and the passing of time. There seems to be a sense of powerlessness and vulnerability in the uncertainty and in feeling as though life is passing by too fast.

Participant N shared her vulnerability concerning her life journey in the following reflection:

"Life is a journey and this staircase is a depiction of how long and tedious the path to success or making a difference is. I feel massively vulnerable as I have doubts as to whether I will have enough drive to reach the top in terms of my academics, expectations and life goals. Life's journey is often overwhelming, and a person is enveloped with much vulnerability as to whether they can achieve the goals they have set, without being tripped only falling and having to slowly start from the bottom all over again. Furthermore, what makes a person certain that the staircase (Path of life) that they chose is correct? What can protect a person from being rejected when almost at the top?" (Participant L).

A large percentage of the sample related the theme of uncertainty to their life journey and the direction they are heading as a source of vulnerability.

Mental health

Struggling with mental health issues emerged as a significant theme in the data. Participant O shared a photo titled "Weight", of a bathroom scale and a pair of running shoes. She related her struggle with self-esteem and body image and how this has been a source of vulnerability for her.

Participant M shared a photo titled "Unstable ", of a building on the edge of toppling over. It appears as though the foundation of the building is unstable, placing the entire structure at risk. The image relays fear of the debilitating effect of struggling with mental health issues and how it can impact all aspects of life.

Participant J shared her experience as follows: "It's tough and there are difficult days" (Participant J).

Throughout participants' reflections, low self-esteem was frequently mentioned. Students seemed to relate many of the vulnerabilities experienced in the other themes with their struggle with self-esteem. The experience of vulnerability also seems to impact how they feel about themselves.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the study was to explore and understand students' experiences of vulnerability in the education faculty in a higher education context in South Africa. The findings showed that vulnerability for these students included a variety of factors, such as the confrontation with themselves, uncertainty of the future, a need for connection, and mental health.

The study also found that students experienced the confrontation with themselves, specifically coming to terms with their "dark sides" and uncomfortable feelings about themselves, as a source of vulnerability. Konstam (2015, 17) attributes this identity negotiation to the developmental phase of young adulthood. In our current age, the boundless representations of self and career for emerging and young adults infinitely complicates the task of developing a coherent identity (Konstam 2015, 17).

Cote (2000, 815) takes the position that the task of navigating who one is has always been multifaceted, and the era in which we live has made it more difficult. A myriad of choice is challenging, and emerging adults struggle individually. Sanders and Bradley (2005, 299) define "identity development" as "neither unchallengeable nor constant; however, it is primarily dependent on external eventualities and prone to change". Identity is ultimately a multidimensional construct characterised by shifts in the sense of self; it may vary over time and across settings (Arnett and Tanner 2006). Therefore, young adults may find themselves needing time to redirect paths and adapt meanings when chaos and loss surface from the unknown (Konstam 2015, 20).

The task of exploring one's identity and the self is often accompanied by feelings of fear, shame and guilt. The participants associated the uncomfortable parts of themselves with terms such as "grotesque" and "dark". Daniels (2013, 23) relates these parts of the self to the Jungian model of the psyche, where the "shadow" refers to those parts of our psyche not illuminated by our consciousness, and that we have learned as unacceptable to express. Also, according to Levine (2010), these parts of the self, refer to past trauma, suggesting that trauma could cause us to repress parts of ourselves we were told were unacceptable.

The study further identified that students experienced uncertainty about the direction of their lives, which was a significant source of vulnerability. Research seems to support that emerging adulthood is the most volitional period of life. Young adulthood is the time when individuals are most likely to be free to pursue their own interests and desires, and this pursuit leads them in a remarkably wide range of directions (Konstam 2015, 22). Although the freedom of choice may seem liberating, it appears to be a double-edged sword.

Hassler (2010) unpacks the various challenges that young adults face when confronted with an abundance of choices. Many of these young adults are confronted with the perceived burden of making good choices in the face of high expectations that are often driven by society, their cultures and family members. The key questions of "who am I" and "where am I going" become overwhelming to the emerging adult who feels overwhelmed by the idea that it is entirely up to them to figure it all out (Cote 2000, 816).

Porfeli and Savickas (2012, 748) support this line of argument further by stating young adults seem to be in a time of their lives where rules are vague and seem to be more contextual in nature. There is also less established guidance pointing to clear developmental paths. Their current phase of life therefore requires greater manoeuvrability, adaptability, and flexibility.

The data further suggested that students experienced a need for connection. This need is important, as research proposes university students have a lower risk of mental health problems when they experience connectedness and interrelatedness (Drum et al. 2017, 169). Social belonging is also defined as a sense of "relatedness" (Ryan and Deci 2000, 68) that arises from "lasting, positive, and significant interpersonal relationships" (Baumeister and Leary 2017, 497). Studies have identified that a sense of belonging, an apparent connection to others and supportive relationships with friends, family or peers effectively mitigate the risk factors of psychological stress among university students (Stallman 2010, 250; Andrews and Wilding 2004, 510). Earl (2019, 232) further suggests that having healthy relationships and flourishing connections can support students in improving mental and emotional wellbeing, their confidence, and their educational journey.

A key theme that became evident from the data was that students experienced their mental health as a source of vulnerability, and research seems to support this concerning trend. According to Stallman (2010, 249), the mental health of university students and the impact of untreated or unrecognized mental illness has been a growing global concern, considering the fact that this could have a significant effect on students and institutions. Deasy et al. (2014, 1) further state that students in programmes with practicum components, such as teachers, are exposed to additional stressors that may further increase their risk for psychological distress. According to research conducted by Bayram and Bilgel (2008, 667), university students experience increased psychological stress compared to the general population.

Despite the fact that mental illness has a significant impact on student's capacity, they still seem to delay, or avoid seeking help. Consequently students are, at any one time, attempting to complete their higher education studies while simultaneously coping with high levels of psychological stress and emerging or existing mental illness. This in turn leads to heightened feelings of vulnerability and worry (Wynaden, Wichmann, and Murray 2013, 846). In addition, Jirdehi et al. (2018, 2) highlight the relationship between self-esteem and mental health. Their research further suggests that low self-esteem significantly affects university students' academic achievement.

The findings of this study propose that students attribute their experiences of vulnerability to confrontations of themselves and the identity formation process common to the young adult developmental stage; uncertainty about the direction of their chosen life path; a need for connection; and psychological stress. The data seem to support a need for increased awareness at higher education institutions of students' mental health and wellbeing. This population's unique developmental phase, psychological stress, and high rates of mental health issues require urgent and systemic interventions. These interventions should ideally not just focus on individuals who seek help from student services but also be tailored to a general student population, since most students are experiencing their unique developmental stage and would benefit from support towards their wellbeing. Individual support should be destigmatised and made more readily available. The data further suggest that interventions should focus on personal connection.

IMPLICATIONS FOR HIGHER EDUCATION

This research contributes to the body of literature in vulnerability studies, which up until recently have mostly focused on the vulnerability of population groups such as children, the elderly and other vulnerable population groups. A gap in the research exists that contextualises vulnerability as a lens through which wellbeing can be explored in a Higher Education context and within the life stage of young adulthood.

This study highlights the necessity of addressing wellbeing of students in Higher Education spaces and looks at vulnerability in relation to their life stage and their mental health. What makes this research important is that studies confirm that elevated levels of student wellbeing have been shown to be linked with an array of positive outcomes, including good relationships, creativity and productivity, pro-social behaviour, effective learning, life expectancy and good health (Huppert and So 2013).

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The study's limitations include that data were collected at only one tertiary institution. Furthermore, the recruitment of participants, the information session regarding the research, as well as the reflections, were conducted in English, which is the second language of most participants in the study. Finer distinctions of experiences of vulnerability may therefore not have been captured. Although multiple photos were analysed for each participant and the collected data were rich, the sample size was small and certain demographic groups were underrepresented.

CONCLUSION

This study shines a light on how student teachers experience the concept of vulnerability. This phenomenon was uniquely explored through a visual participatory method using photos to capture their distinctive experiences. The data foregrounds the unique challenges posed by the students' developmental stage, their need for connection in the higher education space, their struggle with uncertainty and the direction in which their lives are going, and finally, dealing with mental health issues.

REFERENCES

Andrews, Bernice and John M. Wilding. 2004. "The relation of depression and anxiety to life-stress and achievement in students." British Journal of Psychology 95(4): 509-521. [ Links ]

Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen and Jennifer Lynn Tanner. 2006. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. American Psychological Association Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Auerbach, Randy P., Jordi Alonso, William G. Axinn, Pim Cuijpers, David D. Ebert, Jennifer G. Green, Irving Hwang, Ronald C. Kessler, Howard Liu, and Philippe Mortier. 2016. "Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys." Psychological Medicine 46(14): 2955-2970. [ Links ]

Auerbach, Randy P., Philippe Mortier, Ronny Bruffaerts, Jordi Alonso, Corina Benjet, Pim Cuijpers, Koen Demyttenaere, David D. Ebert, Jennifer Greif Green, and Penelope Hasking. 2018. "WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders." Journal of Abnormal Psychology 127(7): 623. [ Links ]

Baik, Chi, Wendy Larcombe, and Abi Brooker. 2019. "How universities can enhance student mental wellbeing: The student perspective." Higher Education Research & Development 38(4): 674-687. [ Links ]

Baumeister, Roy. F. and Mark R. Leary. 2017. "The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation." Psychological Bulletin 117(3): 497-529. [ Links ]

Bayram, Nuran and Nazan Bilgel. 2008. "The prevalence and socio-demographic correlations of depression, anxiety and stress among a group of university students." Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43(8): 667-672. [ Links ]

Braidman, Isobel, Maria Regan, and Julia Humphreys. 2018. "12 Personal and professional developments." In "Wellbeing in Higher Education: Cultivating a Healthy Lifestyle Among Faculty and Students". Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Brown, Brené. 2015. Rising Strong: The Reckoning. The Rumble. The Revolution. Random House. [ Links ]

Capous-Desyllas, Moshoula and Nicole F. Bromfield. 2018. "Using an arts-informed eclectic approach to photovoice data analysis." International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17(1): 1609406917752189. [ Links ]

Cote, J. E. 2000. "Arrested Adulthood: The Changing Nature of Maturity and Identity." Adolescence 35(140): 815. [ Links ]

Daniels, Michael. 2013. "Traditional roots, history, and evolution of the transpersonal perspective." In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Transpersonal Psychology by Harris L. Friedman and Glen Hartelius, 23-43. Oxford, Wiley Blackwell. [ Links ]

Deasy, Christine, Barry Coughlan, Julie Pironom, Didier Jourdan, and Patricia Mannix-McNamara. 2014. "Psychological distress and coping amongst higher education students: A mixed method enquiry." Plos one 9(12): e115193. [ Links ]

Drum, David J., Chris Brownson, Elaine A. Hess, Adryon Burton Denmark, and Anna E. Talley. 2017. "College students' sense of coherence and connectedness as predictors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors." Archives of Suicide Research 21(1): 169-184. [ Links ]

Earl, Diana. 2019. "The healthy relationships series: An untapped potential for human connection." JANZSSA - Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Student Services Association 27(2): 231235. [ Links ]

Eloff, Irma. 2021. "College students' well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory study." Journal of Psychology in Africa 31(3): 254-260. [ Links ]

Frankl, Viktor. 1985. The unconscious god. New York: Washington Square Press. [ Links ]

Harrer, Mathias, Sophia H. Adam, Harald Baumeister, Pim Cuijpers, Eirini Karyotaki, Randy P. Auerbach, Ronald C. Kessler, Ronny Bruffaerts, Matthias Berking, and David D. Ebert. 2019. "Internet interventions for mental health in university students: A systematic review and metaanalysis." International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 28(2): e1759. [ Links ]

Hassler, Christine. 2010. 20-Something, 20-Everything: A Quarter-life Woman's Guide to Balance and Direction. New World Library. [ Links ]

Hawkins, Y. 2019. "Mental wellbeing: Let's find new ways to support students." Office for Students (blog). 9 February. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/blog/mental-wellbeing-let-s-find-new-ways-to-support-students/. [ Links ]

Henning, M., C. Krägeloh, Rachel Dryer, Fiona Moir, R. Billington, and A. Hill. 2018. Wellbeing in higher education. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hergenrather, Kenneth C., Scott D. Rhodes, Chris A. Cowan, Gerta Bardhoshi, and Sara Pula. 2009. "Photovoice as community-based participatory research: A qualitative review." American Journal of Health Behavior 33(6): 686-698. [ Links ]

Hone, Lucy Clare, Aaron Jarden, Grant M. Schofield, and Scott Duncan. 2014. "Measuring flourishing: The impact of operational definitions on the prevalence of high levels of wellbeing." International Journal of Wellbeing 4(1). [ Links ]

Hoshi, Miwako. 2008. "Self-Transcendence, Vulnerability, and Well-being in Hospitalized Japanese Elders." Order No. 3336593, The University of Arizona. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/self-transcendence-vulnerability-well-being/docview/304685159/se-2?accountid=14717. [ Links ]

Huppert, Felicia A. and Timothy T. C. So. 2013. "Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being." Social Indicators Research 110(3): 837-861. [ Links ]

Ito, Ai and Michelle C. Bligh. 2016. "Feeling vulnerable? Disclosure of vulnerability in the charismatic leadership relationship." Journal of Leadership Studies 10(3): 66-70. [ Links ]

Janik, Manfred. 2015. "Meaningful work and secondary school teachers' intention to leave." South African Journal of Education 35(2): 1008-1009. [ Links ]

Jirdehi, Maryam Mirzaee, Fariba Asgari, Rasool Tabari, and Ehsan Kazemnejad Leyli. 2018. "Study the relationship between medical sciences students' self-esteem and academic achievement of Guilan university of medical sciences." Journal of Education and Health Promotion 7(1): 52. [ Links ]

Johnson, Sheena, Cary Cooper, Sue Cartwright, Ian Donald, Paul Taylor, and Clare Millet. 2005. "The experience of work-related stress across occupations." Journal of Managerial Psychology 20(2): 178-187. [ Links ]

Keyes, Corey L. M. and Jonathan Haidt. (Ed.). 2003. Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Keyes, Corey L. M. and Eduardo J. Simoes. 2012. "To flourish or not: Positive mental health and all-cause mortality." American Journal of Public Health 102(11): 2164-2172. [ Links ]

Kidger, Judi, David Gunnell, Lucy Biddle, Rona Campbell, and Jenny Donovan. 2009. "Part and parcel of teaching? Secondary school staff s views on supporting student emotional health and well-being." British Educational Research Journal 36(6): 919-935. [ Links ]

Konstam, Varda. 2015. "Emerging and young adulthood. " Multiple perspectives, diverse narratives. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Lenette, Caroline and Jennifer Boddy. 2013. "Visual ethnography and refugee women: nuanced understandings of lived experiences." Qualitative Research Journal 13(1): 72-89. [ Links ]

Levine, Peter A. 2010. In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books. [ Links ]

Maslow, Abraham Harold. 1971. The farther reaches of human nature. Vol. 19711. New York: Viking Press. [ Links ]

Melchior, Maria, Lisa F. Berkman, Isabelle Niedhammer, Marie Zins, and Marcel Goldberg. 2007. "The mental health effects of multiple work and family demands." Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 42(7): 573-582. [ Links ]

Messerly, John. 2017. "Summary of Maslow on Self-Transcendence. Reason And Meaning." https://reasonandmeaning.com/2017/01/18/summary-of-maslow-on-self-transcendence/. [ Links ]

Moletsane, Relebohile, Naydene de Lange, Claudia Mitchell, Jean Stuart, Thabsile Buthelezi, and Myra Taylor. 2007. "Photo-voice as a tool for analysis and activism in response to HIV and AIDS stigmatisation in a rural KwaZulu-Natal school." Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health 19(1): 19-28. [ Links ]

Morgan, Blaire and Laura Simmons. 2021. "A 'PERMA' Response to the pandemic: An online positive education programme to promote wellbeing in university students." In Frontiers in Education 6: 172. Frontiers. [ Links ]

Morgan, David L. and Kim Hoffman. 2018. "Focus groups." In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection, ed. Uwe Flick. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [ Links ]

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Naiara, Naiara Berasategi Santxo, Nahia Idoiaga Mondragon, and María Dosil Santamaría. 2021. "The psychological state of teachers during the COVID-19 crisis: The challenge of returning to face-to-face teaching." Frontiers in Psychology 11: 3861. [ Links ]

Pollard, Elizabeth L. and Patrice D. Lee. 2003. "Child well-being: A systematic review of the literature." Social Indicators Research 61(1): 59-78. [ Links ]

Porfeli, Erik J. and Mark L. Savickas. 2012. "Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-USA Form: Psychometric properties and relation to vocational identity." Journal of Vocational Behavior 80(3): 748-753. [ Links ]

Radnofsky, Mary L. 1996. "Qualitative models: Visually representing complex data in an image/text balance." Qualitative Inquiry 2(4): 385-410. [ Links ]

Reed, Pamela G. 2008. "Theory of self-transcendence." Middle Range Theory for Nursing 3(2008): 105 -129. [ Links ]

Reed, Pamela G. 2009. "Demystifying self-transcendence for mental health nursing practice and research." Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 23(5): 397-400. [ Links ]

Ryan, Richard M. and Edward L. Deci. 2000. "Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being." American Psychologist 55(1): 68. [ Links ]

Sanders, Jo-Ann Lipford and Carla Bradley. 2005. "Multiple-Lens paradigm: Evaluating African American girls and their development." Journal of Counseling & Development 83(3): 299-304. [ Links ]

Seligman, Martin E. P. 2011. "Building resilience." Harvard Business Review 89(4): 100-106. [ Links ]

Smith, Mary Jane and Patricia R. Liehr. 2018. Middle range theory for nursing. Springer Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Stallman, Helen M. 2010. "Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data." Australian Psychologist 45(4): 249-257. [ Links ]

Stansfeld, Stephen Alfred, F. R. Rasul, J. Head, and N. Singleton. 2011. "Occupation and mental health in a national UK survey." Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 46(2): 101-110. [ Links ]

Wynaden, Dianne, Helen Wichmann, and Sean Murray. 2013. "A synopsis of the mental health concerns of university students: Results of a text-based online survey from one Australian university." Higher Education Research & Development 32(5): 846-860. [ Links ]