Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.37 n.1 Stellenbosch Mar. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/37-1-5677

SPECIAL SECTION

A model for scholarship of engagement institutionalization and operationalization

C. HartI; P. DanielsII; P. September-BrownIII

IUniversity of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. Community Development, Faculty of Community and Health Sciences. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6226-9652

IIUniversity of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. Community Engagement Unit. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3622-2284

IIIUniversity of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. Community Engagement Unit. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5221-3994

ABSTRACT

Transformation policies have been a high priority for governments globally, regionally, and nationally to address past inequalities. Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are the critical stakeholders that ensure societal transformation. This requires HEIs to reimagine community engagement, with a necessary role-shift from Mode 1: provider of disciplinary knowledge to Mode 2: distributor of knowledge to broader society through engagement and research that is inclusive and impactful. In this article, we present an adapted version of Boyer's Scholarship of Engagement (SoE) model, to assist HEIs with the institutionalization and operationalization of engaged scholarship, inclusive of some factors and examples to consider for the process. The operationalization of the model helps HEIs to progress toward assessing their SoE effectiveness and, ultimately, their Societal Impact (SI) contribution, to transform society, responsively and responsibly.

Keywords: Scholarship of Engagement, Community Engagement, Scholarship of Engagement Model, Community-University Partnerships, Knowledge Management Systems, Societal Impact.

INTRODUCTION

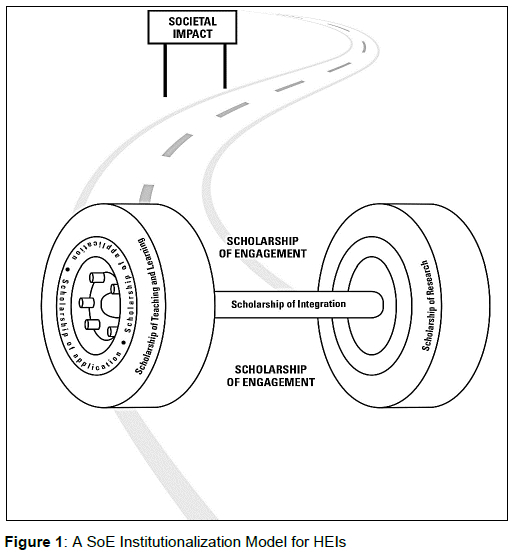

Through this article, we aim to contribute to the theme of reimagining community engagement within the context of a responsive, responsible, and transformative university. To do this, we argue that Community Engagement (CE) includes various types of communities, namely, the scholarly, student, business/industry/government, and civil society communities. Scholarship implies action, and we present an adapted version of Boyers' (1990) Scholarships Model to institutionalize (action) the Scholarship of Engagement (SoE). The SoE is presented as the road towards transformation. The remaining scholarships, namely, Research and Theory into Practice (teaching and learning), are the wheels that are held together by the Scholarship of Integration as the axle. The Scholarship of Sustainable Communities is the nuts and bolts of the wheel. The destination for the SoE road is Societal Impact (SI - also referred to as Broader Impact (BI) in the USA). Therefore, the SoE must be explicitly institutionalized, and represented in all forms of scholarship, as well as at all institution levels, to ensure transformation towards SI. Lazarus et al. (2008, 60) reviewed HEIs in their study, and observed that a deliberate institutional strategy or philosophy, which stresses CE as a core function of the academy, was not the motivation or reason for CE to be embraced as the third pillar. It was the outcome of innovative academics, who championed CE and its implementation. Consequently, the University of Western Cape embarked on this path of institutionalization.

BACKGROUND

Transformation policies, aimed at addressing past inequalities in the higher education sector, have been high on the priority list, since South Africa became a democracy in 1994. Democratic South Africa inherited a polarized society from the Apartheid era (1948-1994), driven by racial segregation and discrimination, resulting in a privileged white minority, to the detriment of other racial groups, which ended up in poverty. Consequently, HEIs need to be responsive to ongoing societal disparities, by effecting positive change through CE.

The South African Higher Education Act (RSA 1997) and White Paper of 1997 (DoE 1997) identified CE, together with Teaching and Research, as the pillars (core responsibilities) of HEIs. The key objective of CE in South African higher education is to "demonstrate social responsibility ... and their [HEIs'] commitment to the common good by making available expertise and infrastructure for community service programmes" (DoE 1997, 10). While HEIs in South Africa, to some extent, have always been involved in CE, the National Plan for Higher Education (Ministry of Education 2001, 7.2) emphasizes the need for "responsiveness to regional and national needs, for academic programmes, research and community service". However, for the greater part of the post-apartheid democratic transformation in higher education, academic scholars have viewed CE as peripheral to their teaching and research roles. This blinkered vision has hampered the ability of HEIs to challenge social disparities in a meaningful, collective, integrative, and acceptable manner.

The HEI sector has, only recently, become more structured, as well as specifically geared towards the assessment and measurement of their CE impact on society. This gear-shift in structural attitude is due mainly to policy changes in research grant applications and internal policies, precisely, scholarship recognition and promotions. However, a great need still exists for HEIs to integrate CE as an infused principle (also see Bender 2008) at all levels and functions to respond in a manner that has a meaningful impact in the South African development context, and is internationally relevant. Ultimately, it is argued that only by explicitly and systematically infusing CE at all levels of HEI institutions can students, parents, faculty members, communities, the business sector, and government, achieve the proposed transformation of society.

In South Africa, each HEI has an office, unit, or centre, responsible for the facilitation, support, and occasionally, the coordination of CE, as part of their organizational structure, to align with the HEIs' legislated roles of Research, Teaching, and Engagement. Each of the HEIs, action (practice) CE in diverse ways, resulting in CE without a standardized practice and standardized CE definition, conceptualization, and approach. However, among the HEIs, there is evidence of some overall CE similarities, which could form a basis for a generic institutionalization process that provides enough scope for academic freedom, while providing a systematic approach for the decentralization of CE, inclusive of all scholarships and levels of the institution.

The HEIs agree that they are knowledge producers, even though some institutions place research as their highest priority, followed by teaching, with engagement as their lowest priority. However, a few HEIs have endeavoured to regard engagement as an infused principle that cuts through all core functions of the institution, as well as across all its levels and sectors, resulting in the Scholarship of Engagement (SoE). As knowledge producers, in the context of SoE for transformation towards SI, several scholars, globally, have challenged the provider of disciplinary knowledge (Mode 1), by arguing that it ought to be supplemented by a distribution of knowledge to broader society (Mode 2), through engagement and research, which are inclusive of, and impactful on society.

Mode 1 knowledge is founded on the Newtonian model, where knowledge is discipline-specific, with a clear distinction between fundamental and applied sciences. Mode 2 knowledge addresses society's integrative and multi-disciplinary nature, which, therefore, requires a different form of knowledge production. Consequently, Mode 2 requires HEI scholars and students to be practitioners, who search for solutions to societal challenges, across disciplines, in an equitable, collective (partnership) manner, with all relevant stakeholders (see Musson 2006; Vo and Kelemen 2014; Waghid 2020).

Waghid (2020), as well as Braskamp and Wergin (1998), argue that Mode 2 should supplement Mode 1, to narrow the gap between HEIs and society, and develop reciprocal partnerships, to ensure social relevance, resulting in improved societal well-being collectively. This is possible, because Mode 2 knowledge production is reflexive, socially accountable, heterogenic, problem-orientated, and multi-, as well as trans-disciplinary. This further highlights the need for university partnerships to succeed with the SI process. In short, Mode 2 requires HEIs to be engaged with societal challenges, stakeholders, and all types of communities. CE, therefore, goes well beyond epistemological (knowledge collaboration and co-creation) and ontological dimensions (Shawa 2020, 105-106). The Universities of the Free State (UFS), Pretoria (UP), Western Cape (UWC), Stellenbosch (SUN), as well as University of KwaZulu Natal (UKZN), started to work towards an explicit Mode 2 SoE practice since the 1980s.

The UWC has adapted Boyer's Scholarship of Engagement (SoE) model to assist HEIs with the conceptualizing, decentralizing, and designing of their transformation practice, which is dependent on SoE towards SI in a standardized, yet broad enough manner, at all levels of the institution and with all types of communities.

ENGAGEMENT AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT BY HEIs

Engagement by HEIs could be extensive, embracing almost all forms of linkages/relations to that of particular formalized partnerships (Hall 2010, 15). HEIs define their engagement within the context of their mission, values, and goals, resulting in variations between institutions (CIC 2005, 4). The Committee on Institutional Cooperation (CIC) in the USA provides an appropriate description for engagement relevant to the proposed institutionalization model in this current paper:

"... engagement is the partnership of university knowledge and resources with those of the public and private sectors to enrich scholarship, research, and creative activity; enhance curriculum, teaching, and learning; prepare educated, engaged citizens; strengthen democratic values and civic responsibility; address critical societal issues; and contribute to the public good (CIC 2005, 2).

The CIC (2005, 4) lists two critical factors, on which the benchmarking of engagement depends. Firstly, the requisite for a joint agreement on the definition for engagement that relates to the missions and contexts of the institution itself and, therefore, not a standardized definition for all HEIs. Secondly, a shared meaning derived from practice, for example, exemplars of engaged teaching, research, and service. Additionally, the CIC (2005, 4) indicates that engagement has three general distinguishing elements:

i) engagement is scholarly - making it both an act of engagement (with partners), and a product of engagement (discipline-generated and evidence-based practice);

ii) engagement cuts across the mission of teaching, research, and service - as it is not a separate activity, but rather, an infused approach by the university; and

iii) engagement is reciprocal and mutually beneficial - in its planning, implementation and outcomes with and by the partners.

These factors indicate the fundamental importance of the need for an explicit systemized SoE process at the university, for an integrative, evidence-based approach that is quality assured and measurable.

The global and national debate, regarding a single definition for CE, continues, because of the mentioned direct relation between the concept and the institution's vision, mission, ethos, and strategic objectives. The proposed SoE model in this current paper adopted the following CE definition of the Carnegie Foundation, not only because, to date, it is the most widely adopted by HEIs, but also the most suitable and representative of contemporary Mode 2 HEIs. The definition is as follows:

"... Community engagement describes collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities [local, regional/state, national, global] for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity (Carnegie Foundation 2020, 2).

The quoted engagement and CE definitions emphasize several aspects relevant to, and required for, the proposed SoE Institutionalization model, namely, collaboration, community types, mutually beneficial exchange, and partnerships, which essentially form a collaborative process, towards common goals and outcomes, by way of engaged scholarship. Engaged scholarship cuts across the university's teaching, research, and service core functions (various types of scholarships), and involves co-creating, transferring, applying, and conserving innovative knowledge, for the direct benefit of internal and external community partners. Scholarship is engaged when it involves reciprocal partnerships, and addresses public purposes of social transformation towards SI.

Aphane et al. (2016, 161) argue that the benefits of CE "include regional development; improved quality of life for communities; firm productivity and competitiveness; incorporation of indigenous knowledge as well as cross-disciplinary knowledge production". Therefore, a clear advantage exists for HEIs to embrace the SoE, to facilitate the successful delivery of community engagement as a third pillar. A key concept in the purpose of CE is transformation, which is well suited to the context of HEIs that link with transformative learning, not only in the teaching/tuition offered by HEIs, but also in their research findings and civic-engagement-collective, consequently representing SoE. The significance of transformative learning, as a key component in SoE, lies in the fundamental role that knowledge (in research, tuition, and engagement) plays, when actioned towards social transformation [specifically, SI] (Favish 2010, 34). This fundamental notion could ensure a continuous upward spiral towards improved societal well-being, which aligns well with Boyers' Scholarship of Engagement model and the suggested adopted version for the proposed institutionalization model, as clarified further below.

THE SOE INSTITUTIONALIZATION MODEL FOR HEIs

The University of the Western Cape (UWC), where the proposed model was conceptualized and implemented, recognises and drives the importance of the Scholarship of Engagement (SoE) for social transformation. This is mainly reflected in the strategic decisions made at the executive level, filtered through its: i) institutional plans; ii) graduate attributes that reflect the vision, ethos, and history of the university; iii) teaching and learning approach that is innovative and socially transformative; as well as iv) research that is locally relevant and internationally significant.

Moving from an infused CE principle to an explicit practice, the UWC SoE incorporates five engagement streams: i) engagement through teaching and learning; ii) engaged research; iii) engagement with business, industry, and professional links (partnerships); iv) social and cultural engagement; and v) economic engagement. These streams align with the scholarship types depicted by Boyer (1990), namely: a) scholarship of discovery, pushing back the frontiers of human knowledge; b) scholarship of integration that focuses on producing interdisciplinary knowledge; c) scholarship of sharing knowledge as widely as possible; and d) the scholarship of integration, which implies a scholarship of application from theory to practice. Boyer (1996) states:

"... the academy must become a more vigorous partner in the search for answers to our most pressing social, civic, economic and moral problems, and must [...] commitment to what I call the scholarship of engagement (Boyer 1996, 11).

In addition, Boyer (1996) argues that, although universities had embraced the teaching, research, and service rhetoric by the latter part of the twentieth century, in practice, the emphasis was still on research output for promotion and status. In response, he suggested a four-form scholarship hierarchy, in which discovery is the more critical scholarship, from which integration, application, and teaching grows. Although these are categorized as separate, they should be understood and applied as overlapping functions of HEI scholars.

We argue that the actioning (operationalization) of all four forms of scholarship requires engagement as the fifth scholarship type, which requires solid and meaningful relationships between the university and its types of communities, represented in, and institutionalized through, its vision, mission, strategies, policies, and core functions (T&L, Research, and Service) deliverables. The UWC, therefore, subscribes to an amended version of Boyer's model (see Figure 1), because i) the fifth scholarship was added; ii) some of the scholarships for institutional decentralization and operationalization purposes were reinterpreted (described differently); and iii) the scholarships were interpreted as equally important and mutually interdependent.

This amended model ensures the integration, relevance, and significance of the scholarships to society and, more importantly, deploys the university's resources (human, infrastructure, and financial) more effectively. The SoE institutionalization model is presented in Figure 1, for which each form of scholarship will be described, with its philosophical dimension/s, methodological context and purpose, as well as the types of communities required for each scholarship. The fifth and last scholarship description, the SoE, will contain additional information, to assist with the operational institutionalization of the proposed model.

Scholarship of research

The Scholarship of Research (SoR) aligns with the epistemological dimension. It is driven by the search for truthful knowledge that must be relevant, inclusive, and equitable, to address societal challenges and inequalities. Its purpose and results, therefore, should be innovative, significant, and transformative toward SI. Research needs to be meaningful and significant, to influence policy (science advice), generate innovative solutions to societal challenges, and ultimately, transform society to improved well-being (SI). This aligns with Boyer's scholarship of discovery, in which Boyer (2016, 21) positions the role of universities as "universities, through research, simply must continue to push back the frontier of human knowledge". This implies that ethics must guide research, based on values and principles, which determine the rules of engagement, and level the playing fields, to facilitate equity and reciprocity. This ensures accountability in the process, by all partner communities (scholarly, student, business/industry/government, and civil society), which will lead to the anchoring of research within a context of relevance, as it will be done with the various community partners, and based on the mutually agreed need expressed by the respective partners. According to Douglas (2012, 32), in engaged scholarship, the community (the beneficiary community) is the core collaborator, and the power dynamics in the partner relationship are changed in favour of the beneficiary community. Therefore, the argument for Mode 2 knowledge, which is co-created with the community, is what the SoR emphasises.

Gibbons (2006, 23) uses the words "socially robust knowledge", which is constructed outside of the confines of the university. This is applicable to Mode 2 knowledge, which is valued and aligned with the SoR, due to the co-creative and collaborative manner in which partners work together that facilitates a multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary approach to research. In this mode, knowledge is tested and verified in different contexts for relevance, while it incorporates and values indigenous knowledge. Marks, Erwin, and Mosavel (2015, 220) argue that research, which is implemented in a CE framework, "emphasises co-determination between university and community actors in formulating research questions, and the design of research, as well as determining and assessing potential outcomes that might emerge from the research process". This again alludes to equity, reciprocity, and the need for evidence of SI. The research projects are also important, in terms of impactful knowledge transfer and/or patents, which must be co-owned by the respective communities that recently have become key components in university approaches to creating new knowledge and financial sustainability.

Scholarship of teaching and learning

The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoT&L) replaces what Boyer refers to as the Scholarship of Theory into Practice. The SoT&L aligns with the pedagogical and ontological dimensions. In creating learning and teaching opportunities and sites, interdisciplinary, trans-disciplinary, and inter-professional opportunities must be created to facilitate SoE for social justice and transformation, towards SI. This calls for the development and implementation of innovative methodologies for teaching and learning, which necessitates engaged scholarship, to facilitate the integration of theory and practice, as well as the alignment thereof with student graduate attributes. There needs to be an appreciation for teaching and learning methods, which are championed and utilized by faculties and staff, who are prepared to facilitate learning through knowledge debate and dialogue, as well as the acknowledgement that students possess prior learning and knowledge (indigenous knowledge).

As proposed by Boyer's model, engaged teaching and learning facilitates engagement opportunities, as it enhances and promotes knowledge transformation, instead of the mere transference of information from one learning partner to another. This, in turn, encourages students' learning and understanding, as it facilitates innovation, challenges them to be reflective, and critically engage with the prescribed content, in the context of real-life situations, to be addressed for social transformation. This may require a paradigm shift, as societal problems will be approached differently, and solutions will require a different lens. Therefore, a Mode 2 approach to learning and teaching for the co-creation of knowledge is needed through alternate ways of framing problems and challenges, which should be echoed, or mirrored in the curriculum. This alternate approach, therefore, is dependent on reciprocal partnerships between the student and scholarly communities and, more importantly, with civil society, as well as public and private sector communities. Such partnerships contribute to synergies between research, teaching and learning, as well as student success, not only in qualification achievement, but also in job readiness and the graduate attributes. The graduate attributes of the UWC are: i) a critical attitude towards knowledge; ii) critical citizenship and the social good - a relationship and interaction with local and global communities, as well as the environment; and iii) lifelong learning - an attitude or stance towards themselves.

Scholarship of Integration

The Scholarship of Integration (Sol) brings together (intergrade) the SoR (epistemological dimension) and SoT&L (pedagogical and ontological dimensions), thereby also adding alignment with the axiological dimension. This should be interpreted and actioned as a cyclical process. For scholars, research (derived from the community partners) influences teaching (curriculum and approach) and learning with, and from, the various community partners, which in turn affects subsequent research, teaching and learning, and engagement. Consequently, it is a continuous cycle of facilitation, reflection, learning, integration, and promotion of engaged scholarship in all its forms, made possible through capacity building, mentoring, and coaching, between role-players and stakeholders, towards enhancing partnerships for social transformation. Jansen (2002, 518) identifies "the readiness and orientation of the partners to engage in new forms of knowledge production" as a critical element in Mode 2 knowledge production. According to Jansen (2002, 518), a vibrant partnership could provide the context for the incubation of knowledge, as well as knowledge production that is multi-disciplinary, with a technology-based application. This aligns with Boyer's definition of integration as "giving meaning to isolated facts, putting them in perspective ... making connections across the disciplines, placing specialists in a large context, illuminating data in a revealing way, and educating non-specialists" (Boyer 1990, 18). The integration aspect also implies the need for multi-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary approaches to the SoE, as its application would otherwise not be as impactful to society.

Scholarship of application (Sustainable communities)

The Scholarship of Application (SoA) aligns with the ontological and sociological dimensions; however, it can only bring about sustainable communities when the SoI is a continuous process of action, reflection, and dissemination, with partners from all types of communities. At the UWC, the SoA is not interpreted as mere engagement with geographical communities (citizens), through service learning, volunteering, outreach, and so forth, as described by Boyer. The SoA is conceptualized as engaged scholarship with all community types (student, scholar, society, public, private sector, and civil society communities), emanating from the SoI results/outcomes. Additionally, the SoA requires equitable, multi-dimensional, and multi-level partnerships, to bring about sustainable communities. The SoA will be driven by the needs of, and consequently, the transformation required for, each of the respective community types. This scholarship addresses the usefulness and applicability of knowledge in society, so that it is transformative and socially impactful. This is important, as it holds the generation of new knowledge to a different evaluation standard, based on usability and relevance in the respective community.

The scholarship of engagement

The description of the SoE model, to date, has provided the reinterpreted four-form scholarship model of Boyer. However, the systematic institutionalization of these four scholarship forms, it is argued, requires the SoE (a fifth scholarship). Consequently, the following SoE description takes on a more elaborative form, which should be read in conjunction with the subsequent section on community-university partnerships.

The proposed model interprets the Scholarship of Engagement (SoE) as the overall result achieved, when the four preceding scholarships are actioned through an engaged multidimensional, -methodological and -partner process, which ultimately presents itself and its activities at all levels of the institution for social transformation. Therefore, SoE is the integrative institutionalization of CE, emanating from engaged scholarship types in an evidential manner. Put differently, SoE is the transformation road, on which the axle turns the scholarship wheels on the journey towards SI. The institution must monitor and evaluate the latter in a qualitative and quantitative manner, consequently providing Mode 2 evidence. The systemised evidence-based institutionalization, therefore, will present the institution's footprint (contribution) in social transformation, and ultimately, its progress towards SI, which depends on the improvement of well-being in society.

The purpose of this SoE discussion is not to engage in the philosophical, contextual, and contemporary debate, regarding differentiation between engaged scholarship and the SoE. However, the following brief description of each, for foundational clarity and general agreement, might contribute to the SoE model description thus far. Engaged scholarship is broadly defined as scholarly engagement activities (the actioning of engagement) linked to a knowledge-based approach of either teaching, research, and/or service, for the direct benefit of a target audience, with emphasis on activities (McNall et al. 2009, 318). Several decades ago, the emergence of the engaged scholarship requirement by HEIs brought about the surfacing of the related form, with an attempted distinction, namely, the Scholarship of Engagement (SoE).

SoE is viewed as more than simply engaged activities. The difference is captured in the transition from one to the other. Consequently, SoE follows on from engaged scholarship, when HEI staff reflect on, interrogate, study, write about, disseminate, and ultimately, incorporate scholarship in all their activities, policies, guidelines, and so forth, at all levels of the institution (McNall et al. 2009, 318-319). This description aligns closely with Boyer's use of the term to describe his four-form SoE model. Engagement is only possible when more than one party is involved; thereby, indicating the importance of partnerships to the SoE. So far, the types of communities (partners) to be involved in each of the scholarships have been briefly indicated; however, the relational context and importance of partnerships to CE have not been described yet.

COMMUNITY-UNIVERSITY PARTNERSHIPS

Globally, community-university partnership sustainability presents a mixed picture. It is relatively well developed in the USA and Australia, with university-wide structures in place to provide ongoing support for activities intended for social transformation and SI. It is still quite exceptional in the UK and South Africa (Northmore and Hart 2011, 2-3). The concept of community-university partnership is often used in combination with community engagement, service learning, and civic (civil society) engagement. Although, at large, they are very similar in process, we argue for a distinction of the community-university partnership concept, specifically regarding the term, partnership, which deserves independent and closer examination, when exploring the roles of the partners.

Generally, community-university partnerships simply appear to involve multiple members with a common goal. However, when examined more closely, it becomes clear that each member enters the partnership with individual, role-specific interests, and expectations that are more specific, as well as more important to themselves than to the other partners. Individual, role-specific interests and expectations are necessary for partnerships; however, the levels, as well as types of interest and expectations, should be in a healthy balance, to create and sustain a partnership (Cox 2000, 9-10; Holland et al. 2003, 3). Too often, partnerships are launched with a project-specific focus or funding opportunity; however, insufficient attention is given to the actual implications for, and expectations of, the participants in the project, resulting in the partners simply assuming that they understand each other's motivations.

Bringle, Clayton, and Price (2009, 4) also call for a distinctive focus on partnership in community-university partnerships, by suggesting a deeper analysis of relationships and partnerships. These authors are of the opinion that relationships become partnerships because of a closeness that develops, through interactions among the partners that possess particular qualities, such as reciprocity, trust, honesty, and good communication, which all link closely to the ethics of engagement. Bringle, Clayton and Price (2009, 6, 11, 12, 15) and Wilson (2004, 20) highlight the complexity of community-university partnerships, due to the cultural differences between higher education and the community, in terms of how each generates knowledge and solves problems. These authors refer to community-university partnerships that, too often, are rooted in the expert model (very closely linked to Mode 1), frequently being applied by university staff, instead of a social justice and transformation approach (more closely related to Mode 2). The expert model is characterised by elitist, hierarchical, and unidimensional relationships, instead of collegial, participatory, cooperative, and democratic. Walsh (2006, 45) highlights that, even if a justice approach to the relationship is followed, the mere order and structural differences of universities and community types may conflict, resulting in role and participation equality challenges. Therefore, the term, relationships, is proposed as the general and broad term for all kinds of interaction/engagements between persons. Simultaneously, the term, partnership, relates to the relationships in which the interactions/engagements possess three particular qualities, namely, closeness, equity, and integrity.

Successful SoE university-community partnerships should demonstrate the following seven key features:

i) the linking of human needs with societal problems, issues, and concerns;

ii) the direct application of knowledge to human needs, societal problems, issues, and concerns;

iii) utilization of professional and academic expertise;

iv) the ultimate purpose of public or common good;

v) the generation of new knowledge for the target groups in the community and the discipline;

vi) a clear relationship between programme activities and HEI's mission; and

vii) a commitment to long-term engagement (Wilson 2004, 18-23).

However, SoE partnerships are faced with diverse challenges, such as diversity, power relations, history, assumptions, time, resources, and logistics that set the context in which engagement transpire (Machimana, Sefotho, and Ebersöhn 2017, 177, 187; Northmore and Hart 2011, 5).

OPERATIONALIZATION OF THE SOE INSTITUTIONALIZATION MODEL

The operationalization of the SoE institutionalization model might require a paper of its own; however, it is anticipated that the following brief discussion about operationalization levels and factor areas, linked to a few examples from our experience, might aid the reader's process of operationalizing the SoE institutionalization model.

SoE institutionalization should be implemented at three levels: i) executive; ii) middle; and iii) foundational; to facilitate the acceptance and uptake at all levels, across, as well as from the top down and the bottom up. The planned approach to implementation ensures that executive leadership is committed and motivated to champion the SoE, thereby guaranteeing sustainability through resource allocation (human, infrastructural and financial), to support the institutionalization process. The middle level is where a dedicated office, in this current case, the Community Engagement Unit (CEU), provides direction and support for the institutionalization process. This is accomplished by following an integrative approach of collaborating with deans, heads of departments, and directors of centres and units, to facilitate partnerships with all stakeholders, on and off campus. The foundational level is where an operational approach is applied, as it involves motivation for buy-in and participation by all academic and support staff in the respective faculties. Their commitment pledge, through the integration of theory and practice, in all three core functions (teaching and learning, research, and engagement), will contribute towards the journey of SI. Therefore, it is vital to create a culture of knowledge sharing, as it would ensure the development of partnerships, the tracking and presentation of the institution's SoE projects, and its SoE knowledge dissemination (publications). This necessitates the design of Knowledge Management Systems (KMSs), such as databases, which presents the SoE contributions by the university.

At the UWC, two main databases were developed: i) SoE projects; and ii) SoE knowledge output (publications); which resulted in knowledge sharing on and off campus. The project's database was launched in 2014, highlighting various forms of CE activities across campus, accessible to everyone, both on and off campus. This database presents an overview of various CE projects at the university, sourced from the office of the Rector, Deputy Vice-Chancellor: (DVC): Academic, DVC: Research and Innovation, DVC: Student Development and Support, all seven faculties and their respective schools, centres, institutes, departments and support units. An annual data collection process, using a template-data collection form, ensures that the information on the database is updated, with maintenance, as an ongoing process. Additionally, the existing project database template form has been expanded this year to also incorporate key objectives of different development drivers at the national level (NPC 2012), regional level (AUC 2015), and international level (UN 2015).

The publications database acknowledges the research conducted by engaged scholars and presents evidence of the university's social transformation contributions to society. The database currently presents publications of engaged scholars from 2015 to 2021. The publications are outlined according to the various disciplines, clustered together in the respective faculties. The database uses a template-data collection form to ensure its annual update and maintenance. This database also contributes towards establishing partnerships, as it has a keyword and an authors' search function.

The UWC is currently in the process of incorporating these two databases into a centralized KMS Web portal. The aim is for the web portal to have a central KMS that could be deployed to assess the effectiveness of the incorporated teaching and transmission of knowledge, through research and application. Factors that could provide an integrated measurement framework range from strategy policy through executive administration, budgets and resources, infused teaching and learning, innovative research backing, multi-disciplinary partnerships and stakeholder engagement, to multi-level empowerment sustainability and community feedback.

The overall design of the web portal KMS is founded on the factor areas suggested by Friedman, Perry, and Menendez (2013, 8-10), to assist HEIs with the classification, planning, implementation, assessment, and reporting of their engagement status, thereby presenting its SoE in a central space. Each of the ten factors are presented, including a few general examples:

i) part of the institutional mission and strategic plan: engagement is declared as part of the HEIs' mission statement and further expanded in its strategic plan;

ii) built into executive administration: the portfolios of the executive administration present engagement efforts in students, teaching and learning, as well as research;

iii) institutionalized in policy: these policies present guidelines for the actioning of engaged scholarship in all it is forms (the SoE Model), inclusive of innovative pedagogy, professional development (promotion and scholarship awards);

iv) imbedded in teaching and learning: it is presented in the teaching, learning, and assessment policies, inclusive of the programme curriculum reviews that are transformative in approach and implementation;

v) supported by innovative research: it informs teaching and learning, student development, as well as contributes to SI in a local, national, and international manner, through multilevel stakeholder partnerships;

vi) included in budgets and resource allocations: the more challenging need to track, in the absence of various engagement databases, with clear project plans representing SMART indicators to be achieved, linked to resources required for the engagement, and assessed against its impact/transformation (community benefit) in society;

vii) monitored and evaluated: a standardized system framework applied to track, assess, and report on the impact of university engagement in society;

viii) sustained with multi-level stakeholder partnerships: a partnership portal that assists with identifying, tracking and/or further developing partnerships;

ix) integrative and multi-disciplinary (whole-society): the university can plan, implement, and assess its impact in the various communities as an engaged institute, and simultaneously articulate it to the national, regional, and international development drivers; and

x) empowering and sustainable: the purpose of the university is to empower communities to drive their own development, and thereby follow a Mode 2 approach, resulting in graduates, who could be active citizens for transformation in the world of work and society at large.

Besides the ten factor areas linked to various databases, the web portal would also provide capacity-building tools, relevant to SoE projects (project proposal writing; project budgeting; project management; and project evaluation). In addition, capacity-building tools would also be provided, related to establishing partnerships, research ethics, specifically data sharing and data ownership, as well as the rules of engagement.

CONCLUSION

Redressing past inequalities that have historically evolved in societies, has become an agreed imperative in the modern world. Ensuring community engagement and development that is, and continues to be, effective, is an exciting challenge for HEIs. Universities are at the core of knowledge growth in the evolution of the fair-and-equal-opportunities societies that are needed in the modern world. This challenge places all - from the chancellor, to the lecturer, to the administrator - on their quest to be innovative, concerned, caring, and effective.

Engagement ranges from the broad concept, to the specific task, with the involvement of diverse communities and partnerships. Factors that could provide an integrated measurement framework range from strategy policy, executive administration, budgets and resources, infused teaching and learning, innovative research backing, multi-disciplinary partnerships and stakeholder engagement, to multi-level empowerment sustainability and community feedback. For some HEIs, it will involve a mind-shift realization that CE is no longer peripheral to teaching, but an interwoven key element (engaged scholarship) in the three core functions of universities.

The SoE model has been presented to assist HEIs with the institutionalization of engaged scholarship, including some factors and examples to consider, when the SoE model, once institutionalized, needs to be operationalized. The operationalization of the model assists with the institution, consequently, being enabled to move towards the assessment of its SoE effectiveness, and ultimately, its SI contribution, to transform society.

Measuring the effectiveness of inequality removal and societal transformation has been prioritized by governments across the globe. To preserve their lead, and maintain their value to and in modern society, HEIs are reviewing and confirming that their policies, practices, knowledge-imparting content and methods, are relevant and meaningful to the people and community types they serve.

REFERENCES

African Union Commission. 2015. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, a Shared Strategic Framework for Inclusive Growth and Sustainable Development. The first ten-year implementation plan (20142023). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: The African Union Commission. [ Links ]

Aphane, Marota, Oliver Mtapuri, Chris Burman, and Naftali Mollel. 2016. "Academic interaction with social partners in the case from the University of Limpopo." Journal of Education 66: 139-184. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i66a06. [ Links ]

AUC see African Union Commission. [ Links ]

Bender, Gerda. 2008. "Exploring conceptual models for community engagement at higher education institutions in South Africa." Perspectives in Education 26(1): 81-95. [ Links ]

Boyer, E. 1996. "The scholarship of engagement." Journal of Public Service and Outreach 1(1): 11-20. [ Links ]

Boyer, Ernest L. 1990. Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Lawrenceville, NJ., USA: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Boyer, Ernest L. 2016. "The scholarship of engagement." Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 20(1): 15-27. [ Links ]

Braskamp, Larry A. and Jon F. Wergin. 1998. "Forming new social partnerships." In The responsive university: Restructuring for high performance, ed. William Tierney, 62-91. Baltimore, MD., USA: Johns Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Bringle, Robert C., Patti Clayton, and Mary Price. 2009. "Partnerships in service learning and civic engagement." Partnerships: A Journal of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement 1(1): 1-20. [ Links ]

Carnegie Foundation. 2020. Executive Summary: Carnegie Community Engagement Classification. Logan, UT: USA: Carnegie Community Engagement Classification Task Force, Utah State University. [ Links ]

CIC see Committee on Institutional Cooperation. [ Links ]

Committee on Institutional Cooperation. 2005. Engaged Scholarship: A Resource Guide (DRAFT). Champaign, IL., USA: Committee on Institutional Engagement. [ Links ]

Cox, David N. 2000. "Developing a framework for understanding university-community partnerships." Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 5(1): 9-26. [ Links ]

Department of Education. 1997. Programme for the Transformation on Higher Education: Education White Paper 3. General Notice 1196 of 1997 (July 1997). Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa: Government Printer. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/18207gen11960.pdf. (Accessed 24 June 2022. [ Links ])

DoE see Department of Education. [ Links ]

Douglas, Sharon. 2012. "Advancing the scholarship of engagement: an institutional perspective." South African Review of Sociology 43(2): 27-39. [ Links ]

Favish, Judy. 2010. "Towards developing a common discourse and a policy framework for social responsiveness." In Community engagement in South African higher education: Kagisano No. 6, ed. M. Hall, 89-103. Brummeria, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa: The South African Council on Higher Education. [ Links ]

Friedman, Debra, David Perry, and Carrie Menendez. 2013. The Foundational Role of Universities as Anchor Institutions in Urban Development. Washington, DC., USA: Coalition of Urban Serving Universities. [ Links ]

Gibbons, Michael. 2006. Engagement as a core value in a mode 2 society. Keynote address at CHE-HEQC/JET-CHESP Conference on Community Engagement in Higher Education, 3 to 5 September 2006, 19-29. Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa: CHE-HEQC/JET-CHESP. [ Links ]

Hall, Martin. 2010. "Community engagement in South African higher education." In Community engagement in South African higher education, Kagisano No. 6, 1-52. Auckland Park, Gauteng, South Africa: Jacana Media. [ Links ]

Holland, Barbara A., S. Gelmon, L. W. Green, E. Greene-Moton, and T. Stanton. 2003. "Community-university partnerships: Translating evidence into action." In National Symposium on Community-University Partnerships, April 2003, San Diego, CA., 3-4. Raleigh, NC., USA: Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH)/Washington, DC., USA: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's Office of University Partnerships (OUP). [ Links ]

Jansen, Jonathan D. 2002. "Mode 2 knowledge and institutional life: Taking Gibbons on a walk through a South African university." Higher Education 43(4): 507-521. [ Links ]

Lazarus, Josef, Mabel Erasmus, Denver Hendricks, Joyce Nduna, and Jerome Slamat. 2008. "Embedding community engagement in South African higher education." Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 3(1): 57-83. [ Links ]

Machimana, Eugene Gabriel, Maximus Monaheng Sefotho, and Liesel Ebersöhn. 2018. "What makes or breaks higher education community engagement in the South African rural school context: A multiple-partner perspective." Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 13(2): 177-196. [ Links ]

Marks, Monique, Kira Erwin, and Maghboeba Mosavel. 2015. "The inextricable link between community engagement, community-based research and service learning: The case of an international collaboration." South African Journal ofHigher Education 29(5): 214-231. [ Links ]

McNall, Miles, Celeste Sturdevant Reed, Robert Brown, and Angela Allen. 2009. "Brokering community-university engagement." Innovative Higher Education 33(5): 317-331. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education. 2001. "National Plan for Higher Education in South Africa." Government Gazette, Vol. 431, No. 22329 (25 May 2001). Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa: Government Printer. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/22329.pdf. (Accessed 24 June 2022). [ Links ]

Musson, Doreen. 2006. "The production of Mode 2 knowledge in higher education in South Africa." PhD dissertation, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

National Planning Commission. 2012. National Development Plan 2030: Our future - make it work, 385-393. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/ndp-2030-our-future-make-it-work.pdf. (Accessed 23 June 2022). [ Links ]

Northmore, Simon and Angie Hart. 2011. "Sustaining community-university partnerships." Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement 4: 1-11. [ Links ]

NPC see National Planning Commission. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. 1997. "Higher Education Act, Act No. 101 of 1997." Government Gazette, Vol. 390, No. 18515 (19 December 1997). Cape Town, Western Cape, South Africa: Government Printer. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a101-97.pdf. [ Links ]

RSA see Republic of South Africa. [ Links ]

Shawa, Lester Brian. 2020. "The public mission of universities in South Africa: Community engagement and the teaching and researching roles of faculty members." Tertiary Education and Management 26(1): 105-116. [ Links ]

UN see United Nations. [ Links ]

United Nations. 2015. "The United Nations Sustainable Development Summit 2015." New York, NY., USA: United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/summit. (Accessed 23 June 2022). [ Links ]

Vo, Linh-Chi and Mihaela Kelemen. 2014. "Moving beyond Mode 1 and Mode 2 of knowledge production by John Dewey's Experimentalism." Academy of Management Proceedings 2014(1): 12564. [ Links ]

Waghid, Yusef. 2020. "Towards an Ubuntu philosophy of higher education in Africa." Studies in Philosophy and Education 39(3): 299-308. [ Links ]

Walsh, David. 2006. "Best practices in university-community partnerships: Lessons learned from a physical-activity-based program." Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 77(4): 4556. [ Links ]

Wilson, David. 2004. "Key features of successful university-community partnerships." In New directions in civic engagement: University Avenue meets Main Street, ed. Kathleen Ferraiolo, 1723. Charlottesville, VA., USA: Pew Partnership for Civic Change. [ Links ]