Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.36 n.5 Stellenbosch Nov. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/36-5-4127

GENERAL ARTICLES

The teaching, learning and assessment of health advocacy in a South African college of health sciences

D. van StadenI; S. DumaII

IUniversity of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa. Department of Optometry. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2028-1711

IIUniversity of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa. Office of Teaching and Learning, College of Health Sciences

ABSTRACT

Health advocacy is a core competency identified by Health Professions Council of South Africa to be acquired by health professional graduates. There is a lack of information on how health advocacy (HA) is taught and assessed in health science programmes. The aim of the study was to explore the teaching, learning and assessment of HA in undergraduate health science programmes at a South African university.

METHODS: Curriculum mapping of eight programmes and a Focus Group Discussion (FGD) with eleven key informants were conducted using a sequential mixed methods approach. Content analysis was used to analyse Curriculum Mapping data. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the FGD data. Results from both data sets were triangulated

RESULTS: Six themes emerged: Perceived importance of HA role for health practitioners; Implicit HA content in curricula; HA as an implicit learning outcome; Teaching HA in a spiral curriculum approach; Authentic Assessment of HA, and Perceived barriers to incorporation of HA into curricula

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS: HA is perceived as an important role for health professionals but it is not explicitly taught and assessed in undergraduate health sciences programmes. Barriers to its teaching and assessment can be addressed through capacity development of academics

Key words: advocacy, authentic assessment, core competencies, curriculum, health advocacy, health advocate, health professions education, health sciences, teaching and learning

BACKGROUND

South Africa is a country characterized by social inequities which inadvertently affect health service provision. In the health professions, activities related to ensuring access to care, navigating the health system, mobilising resources, addressing health inequities, influencing health policy and creating system change are known as health advocacy (Hubinette et al. 2017). Foundational concepts in health advocacy (HA) include social determinants of health and health inequities, which are important factors in addressing inequities within and between countries and regions, especially for developing nations (Friel and Marmot 2011).

The Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) regulates most healthcare professions in the country. Until recently, health professions training programmes in South Africa were primarily focused on training for profession-specific clinical competency. However, given the inherent health system weaknesses in South Africa, and the challenges faced by new graduates working within the public health system, health advocacy has increasingly gained attention as a core competency requirement in health professions training programmes nationally (Knight, Ross, and Mahomed 2017). In 2014, the HPCSA adopted the Core Competencies (Medical and Dental Professions Board of the HPCSA 2014) as an imperative in the teaching and learning programmes for medical and health professions, in line with global movement towards the same (Knight et al. 2017). These core competencies (in addition to the Healthcare Practitioner), include roles of a Scholar, Communicator, Health Advocate, Collaborator, Professional, as well as Leader and Manager, with health advocacy being the competency of interest in this research.

While South African health professions training institutions have increasingly begun adopting these expanded competencies (Van Heerden 2012), efforts appear to be selective based on the educator's expertise and interest in teaching these expanded roles. Evidence however, shows that efforts aimed at matching the knowledge and skills of health professionals to population needs increases productivity and improves quality of care (Langins and Borgermans 2016). Health advocacy education initiatives have also shown to improve student knowledge and engagement in health policy advocacy (Eaton et al. 2017). This is because the teaching and learning of health advocacy enhances the development of fit-for-purpose graduates who will have the core competencies required to address the contextually relevant health challenges upon graduation and entry into the workforce. It further improves the quality of the learner's experience as well as work readiness, particularly within the South African and African contexts where countries and health systems face a myriad of challenges. Finally, it enables students in higher education to understand their broader role in society beyond a reactive, curative healthcare model.

The need for greater public health competencies in the training of health professionals in South Africa has been acknowledged; alongside the need for producing health professionals who are "fit for purpose" and competent in influencing health policies for improving health inequalities in their communities. However, few institutions have systematically looked into translating public health science into health professions training programmes (Hearne 2008). The extent to which efforts to improve the health of a population can be operationalised within health professions training programmes is also not clear (Hubinette et al. 2017).

The need to understand the teaching, learning and assessment of health advocacy within health professions programmes in South Africa, with the overall aim of improving students' skills and knowledge in this area therefore became important. This research therefore set out to investigate the extent to which health advocacy as a core competency within health professions education and training is taught and assessed within health professions training programmes at a South African university.

METHODS

Research setting

The research was conducted within the College of Health Sciences at a South African university. The College is organized across four Schools and offers a total of twelve undergraduate programmes in health sciences and a plethora of postgraduate programmes that lead to different health practitioner specialists. Each School houses a number of undergraduate programmes or disciplines. Academic Leaders and Heads of Schools are responsible for all undergraduate programmes or disciplines, while Specialist Academic Heads are responsible for respective specialist postgraduate programmes. The undergraduate programmes offered include Bachelor Degrees in Audiology, Dental Therapy, Medical Science, Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBChB), Nursing, Occupational Therapy, Pharmacy, Physiotherapy, Speech-Language Therapy, Sport Science and Optometry.

Study design

A sequential mixed method study design was used to explore and describe the teaching, learning and assessment of HA within the undergraduate programmes in the research setting. A sequential mixed methods design was used because it allowed the researchers to have baseline information on the health advocacy content in curricula of the undergraduate programmes through the process of curriculum mapping. This would allow the researchers to explore how such content was taught and assessed through FGD with key informants. Mixed methods designs are useful when the results from earlier phases are needed to inform subsequent phases, providing future direction to the research project (Cresswell 2014).

Convenience sampling was used to obtain all undergraduate health science programmes for curriculum mapping, after obtaining ethical clearance for the research project. A request was made to all Academic Leaders of Health Science Disciplines to submit undergraduate curricula to the Office of Teaching and Learning for curriculum mapping on health advocacy. The Office of Teaching and Learning is managed by the lead author, who is also a Dean. Eight out of twelve programme documents were received for curriculum mapping. The Nursing Science programme was under curriculum review at the time of the study and therefore could not submit their curriculum. However, the nursing programme is not regulated by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA), but by the South African Nursing Council. The two Sport Sciences' programmes are currently also not regulated by the Professional Council and therefore does not ascribe to the demands of the HPCSA. A total of nine undergraduate curricula and related module templates from eight programmes were received for curriculum mapping.

Purposive sampling was used to recruit eleven (11) key informants who were Academic Leaders of Disciplines and were employed in the College of Health Sciences prior to 2014, the year in which the HPCSA's Core Competencies for undergraduate programmes in South Africa (HPCSA 2014) was adopted by the College as a framework for teaching and learning of all its undergraduate programmes.

Phase 1: Curriculum mapping as data collection

A Research Assistant (RA), who had a Masters in Nursing Education qualification and understood the concept of HA, conducted the first phase of curriculum mapping. The RA received all undergraduate programme curricula from participating Schools and was given the following explicit words to search in the broad learning outcomes of each curricula and in related modules: "advocate", "advocacy", "health advocate", "health advocacy" and the following implicit words which are indirectly related to health advocacy: "social justice", "community awareness", "community engagement", "community involvement", "change agent", "health promotion", "marginalized groups". He entered broad learning outcomes for each programme on an Excel document, and extracted words or sentences which were either explicitly and implicitly related to health advocacy.

Data analysis

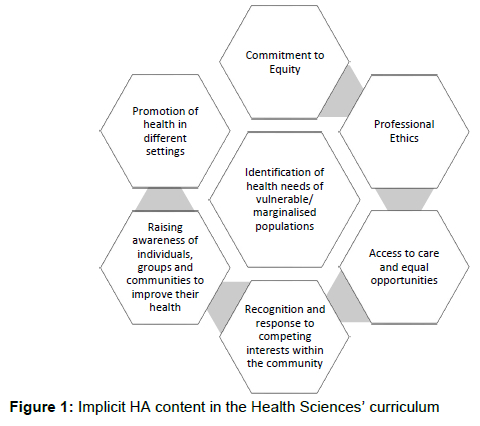

Content analysis was used to analyse data from the curriculum mapping process. Data in the Excel document was read and re-read, with the aim of identifying learning outcomes that were implicit or explicit in preparing the health science students for their health advocacy role. The number of times each implicit or explicit word appeared in each curriculum was calculated and the process was repeated by the first author for validation purposes. Only one curriculum document had an explicit learning outcome related to the health advocacy role of students as health professionals, which was to "act as an advocate for patient or client groups". The rest of the curricular documents had either two or three of the following learning outcomes, which demonstrate implicit commitment to development of health advocacy skills for learners as health practitioners: Identification of health needs of vulnerable/ marginalised populations and respond appropriately; Commitment to equity, access to care and equal opportunities; Raising awareness of individuals, groups and communities to improve their health; Promotion of health in different settings; Recognition and response to competing interests within the community being served; Professional ethics.

Phase 2: Focus group discussion with the key informants

Dilshad and Latifs (2013) basic principles for conducting focus group discussions were used to collect data from the eleven key informants. These include making sure that the concept or phenomenon being discussed and explored is well defined and or explained to ensure similar understanding among all participants; making sure that the FGD is conversational while it remains focused on the main point for discussion. In line with this, the concept and meaning of HA was explained as the health practitioner's use of expertise and influence to advocate for/act on behalf of individuals, communities and populations to advance their health and wellbeing and build capacity for health promotion. The FGD questions asked the participants to discuss the level at which HA was taught and assessed, and to give specific examples on how HA was taught and assessed in their individual programmes. Another critical FGD question was on the challenges they associated with incorporating HA in their individual programmes. The FGD lasted for ninety minutes. Observations of the group's interaction during the FGD was written down as field notes, while the discussions were audio-recorded. The FGD were transcribed verbatim within the 24 hours following data collection. Transcribed data was then stored in a Microsoft Word document for manual data analysis.

Data analysis

Thematic data analysis was used to analyse data from the FGD. The transcribed data was read and reread by the first author, initially focusing on each and every key informant's responses to the questions, by labeling of meaningful sentences during this descriptive coding process. She then focused on the interpretive coding process, which involved focusing on the overall views of all the key informants in response to the teaching and assessment of HA within the College. The hand-written notes taken during the FGD were also analysed and incorporated into the interpretive coding.

Another research team member, not closely related to the data collection process, was given the raw data for re-coding as a measure to ensure credibility of analysed data. There was consensus in the coding. The codes then assigned into categories according to similarities and in response to the research questions. This led to the identification of key themes. Triangulation of data from the FGD and the curriculum mapping was conducted to determine and describe how HA was perceived, taught and assessed.

FINDINGS

Triangulated data revealed six themes including: Perceived importance of HA role for health practitioners; Implicit HA content in curriculum; Health advocacy as an implicit learning outcome; Teaching HA in a spiral curriculum approach; Authentic Assessment of HA and Barriers to full incorporation of HA into health sciences curriculum.

Theme 1: Perceived importance of HA role for health practitioners

The views expressed by all key informants indicate the value attached to HA as a necessary role and competency to be possessed by all health professionals in order to deal with the social injustice, health inequities and negotiate for better health care for the communities in South Africa. Participants indicated that possession of HA as a competency will enable the graduates to be health advocates in all settings. This is reflected in the following quotes:

"The health advocacy role is a necessity for health practitioners, and not just a luxury. We are dealing with diverse populations and diverse people, some of them still don't know what they are entitled to access for their health needs. Health practitioners should help them know." (Academic Leader, MBChB, Male).

"It would be marvellous to introduce health advocacy from the first year of their education because that would set the tone from first year and by the time they reach the exit levels, there is immense progress and growth as health advocates." (Academic Leader, Physiotherapy, Female).

"There is a misperception that the health advocacy role should only happen in the community. Advocating for health can and must happen in the hospital, clinics and even in academia and everywhere. That is where things get lost. It is important that we correct this misperception, health advocacy role is a must for everyone and everywhere." (Academic Leader, OT, Female).

Theme 2: Implicit HA content in the Health Sciences' curriculum

Data from both the curriculum mapping and FGD views shared by the key informants showed that, although HA is valued as an important competency to be possessed by the health professionals, the curricula content, the learning outcomes and skills to be taught are not clearly stated. This is confirmed by the fact that only one out of eight undergraduate curricula documents reviewed during curriculum mapping, had the learning outcome "act as an advocate for patient or client groups" explicitly stated. Other curricula documents had either two or three of the following learning outcomes, which demonstrate implicit commitment to development of health advocacy role for learners as health practitioners (Figure 1).

None of the curricula documents reviewed specified the actual skills that should be possessed by the graduates as health advocates.

The following quotes from different key informants are examples of the theme "implicit HA content in the health sciences' curriculum":

"We teach our students health advocacy in various forms but we are never direct or explicit and say, now this is your health advocacy role." (Academic Leader, Male Dental Therapy).

"In first year, we have a module called community studies where students go out to the community and interact with the community, we do not specify that this is for health advocacy." (Academic Leader, Female, Speech-Language Pathology).

"Students are expected to be change agents, even though nothing clearly states that in the curriculum. There is community engagement, but the students are not aware that health advocacy is what is expected of them. The project is about making a difference in your community, that's all they are told." (Academic Leader, MBChB, Male).

Theme 3: Health advocacy as an implicit learning outcome

This theme is related to implicit content of HA in the health sciences' curriculum, but differs in that unlike just content, there was a hope that by placing the students in the communities or giving them projects which make a difference in communities, that students would develop some health advocacy skills. These unplanned learning outcomes are demonstrated by the following quote, which relates to how the first-year students in one programme are given a project to make a difference in the community close to the College of Health Sciences:

"So, it is basically thrown at them, to go make a difference. Some students take their projects to old age homes, children's homes etc. Other students' projects target homeless people living in the parks. So, they are asked to visit these communities and find out what these communities need ....

The first year experience is amazing, because they need to draw from their own resources and values. They need to start learning, 'what are the social and healthcare needs of community we serve. There is so much they learn in terms of attitudes and values as health advocates, although at that time, they are not even aware of this." (Academic Leader, MBChB, Male).

The same key informant demonstrated how the HA role is as an experiential learning outcome is emphasized later in the programme with the hope that the graduates will become health advocates or develop the necessary attitudes as health advocates when they engage in a quality improvement project as follows:

"We ask students in 4th year as well as 5th year IPC 2 (name of module) to do quite a bit of quality improvement work. We emphasise again, that if they do not make a difference in their service, what kind of health practitioners will they be? So, we urge them to demonstrate change agency skills." (Academic Leader, MBChB, Male).

Another key informant supports the notion of HA as an implicit learning outcome in the following quote:

"We have a module called dental public health, where students have to engage the community members by doing skits and visiting schools for health promotion. In these manners we do hope they also learn advocacy but mostly it is hidden. It is not obvious to the students that they are being trained as health advocates. We hope they will develop this. Perhaps we need to be open about it instead of it being in the hidden curriculum." (Academic Leader, Dental Therapy, Male).

"At the 4th year, we particularly focus on the community placement module. Students have to come up with own health promotion projects and health prevention programmes to disenfranchised/ fairly marginalised communities. They are compelled to do empowerment programmes within those communities like collecting old clothes and giving them to women who would then sell them to earn an income for themselves. Surely they learn some health advocacy during this process." (Academic Leader, Occupational Therapy, Female).

Theme 4: Teaching Health Advocacy in a spiral curriculum approach

There was consensus among all key informants that concepts related to HA were taught in a scaffolding or spiral approach, beginning from earlier years and progressing to senior years. There was also acknowledgement by all key informants that students have no expertise and influence to advocate for/ act on behalf of individuals, communities and populations, in order to advance their health and wellbeing and build capacity for health promotion during earlier years of their education. However, some key informants identified the first and second years of study as the time in which HA-related content was introduced, and when more HA roles were expected from students as demonstrated in the following quotes:

"We actually start introducing the concept of advocacy at the first year of their studies. We could tick some of the boxes in 2nd level because we are doing a lot of it in health promotion, but we further entrench it in the later in the programme. For us, it is important to have a thread of HA throughout in the curriculum. The clinical modules at third and fourth year are where we see a lot of its implementation. The main health advocacy projects are then mainly done at the exit level modules." (Academic Leader, Audiology, Female).

"The theory is taught in first year, where we introduce them to the range of the roles that the speech language therapist plays in the communities as patient advocates. In the 3rd year that is where we start providing them with appropriate interventions for HA role. We provide them with different interventions needed by people who have communication and swallowing disorders as part of their clinical module. That is where they are encouraged to start advocating for quality health care for their clients. At 4th year they have a module where they go out to different communities and they develop and implement a Health Advocacy project with their clients or families." (Academic Leader, Speech Language Therapist).

"In OT, we prepare the students in 1st and 2nd level so that they can be able to implement HA in the 3rd and 4th year. A lot of emphasis is placed at 3rd and 4th year level because we are saying they are almost exiting the programme, and they need to be competent health advocates." (Academic Leader, Occupational Therapy, Female).

The quote below shows that the key informant understood and acknowledged that, the students at first year level do not have expertise to use and influence to advocate for/act on behalf of individuals, communities and populations to advance their health and wellbeing and build capacity for health promotion during earlier years of their education, but this was developed in a spiral approach of teaching:

"The students are required to do a SWOT Analysis in the communities they operate in. For example students in their first year, once they do a SWOT analysis, they would have a theoretical understanding even if they cannot practically do anything about it. Once they get to 2nd year level they have to follow-up to the links they identified in the 1st year, and by 3rd year they plan for the HA intervention." (Academic Leader, Speech Therapist, Female).

"In MBChB, there is are modules called electives 1-3. Towards their July recess, students are asked to go to communities closer to their original homes to do a community diagnosis. When they come back, they indicate what interventions are needed to address the health needs in those communities. They can then follow-up later and advocate for how the identifies needs can be met." (Academic Leader, MBChB, Male).

Theme 5: Authentic assessment of health advocacy

Peer assessment methods in which individual students or small groups of students are critiqued by their peers, poster presentations, reflections on students' engagement with the communities, oral presentations of what students did with and for their communities during the health advocacy projects were listed as assessment methods used to assess students' acquisition of HA-related knowledge and skills. This theme was named authentic assessment of HA because the listed assessment methods are in line with the principles of authentic teaching and assessment (Lombardi 2007) as demonstrated in the following quotes below:

"During the students' presentations, we look at each student's ability to advocate for factory workers' needs in a very generic kind of way. We make comments in relation to the student's efforts in advocacy. Their classmates also have a chance to make comments or ask them for explanations." (Academic Leader, OT, Female).

"They make posters in groups and present it in the classroom. The groups then critique each other's projects like in a forum. We make comments in relation to the student's efforts in advocacy." (Academic Leader, MBChB, Male).

"The poster presentations assessment is a brilliant idea because the students engage and stand up for themselves whilst presenting. Both the students and the teacher learn about what aspect they can add to health advocacy." (Academic Leader, Physiotherapy, Female).

"In the 5th year, the assessment of the health advocacy project is that students present 10 slides in 10 minutes .... Those students thought they had failed the proj ect but then they stood up to me and said: 'Do you know how tough it is to advocate in the community because there are factors beyond our control? But now we know what to consider for future projects.' I gave them 80% because they learnt a major lesson when practising health advocacy." (Academic Leader, MBChB, Male).

Theme 6: Perceived barriers to full incorporation of HA into the undergraduate health sciences' programmes

Data revealed a number of perceived barriers to the full incorporation of HA into the undergraduate health sciences' programmes. These include lack of a common understanding of HA or language to use in developing appropriate HA related learning outcomes, lack of confidence in own assessment methods' abilities to evaluating HA accurately, lack of institutional leadership and resources to support incorporation of HA into the curriculum. This is demonstrated in the following quotes from data:

"On my side, we need training on how to align the learning outcomes with our assessments, to make sure that what we say is our learning outcome is explicitly assessed, in terms of what skills to add in the assessment tool. Secondly, the venues that we use to facilitate the learning of health advocacy and clinical sites for implementation are not that well developed." (Academic Leader, Occupational Therapy, female).

"Can we ever be able to formally assess health advocacy since it is not formally in the curriculum? I don't think so." (Academic Leader, MBChB, Male).

"I think it is important for all the academics involved in the teaching of Health Advocacy to get a common understanding. There has to be training workshops where people obtain a common understanding of what Health Advocacy is and how it is described in the competency framework. There has to be a facilitated kind of process where people have to be brought onboard like we are doing now, where we get an understanding of advocacy at the leadership level, then at the staff level, before it is implemented. We haven't had that yet." (Academic Leader, Pharmacy, male).

An important observation made during the focus group discussion was the unanimous frustration observed when the participants were discussing the barriers to health advocacy. This was observed in the tone and nonverbal gestures used when expressing the barriers. This frustration seemed genuine and different from the earlier excitement observed when participants were discussing different HA projects they engaged their students in. Observing and noting the tone of voice and nonverbal communication throughout the group interaction in field note was found to be very important in matching the information and researchers' interpretation during data analysis. This is supported by Wong (2008).

DISCUSSION

The eleven academic leaders of Disciplines within the College of Health Sciences were purposively selected because of their embedded responsibility in curriculum development and delivery of the curricula that is aligned to the HPCSA's Core Competencies for undergraduate programmes in South Africa (HPCSA 2014), adopted as the framework for teaching and learning in all of the College of Health Sciences' undergraduate programmes. The perceived importance of HA as a role for health practitioners reported in the study is in keeping with global sentiment and an assurance for incorporation and promotion of health advocacy in health sciences curriculum at this institution. In a similar study from the University of Notre Dame Australia, the key academic informants including the Dean, Associate Dean of Aboriginal Health, Head of the University Core Curriculum of Medicine and the Domain Chairs Communication and Clinical Practice selected for the same reasons also reported an appreciation of health advocacy as an important role for health practitioners in that country (Douglas et al. 2018).

The perceived importance of HA as a role for health practitioners is not enough if HA is invisible or implicit in the curricula documents because of a number of negative implications. Firstly, it can lead to discontinuity of teaching and assessment of HA if the academic champions of HA leave the institutions. Secondly, it may affect the accreditation of health sciences' programmes by the regulatory bodies who have formally adopted the HA as one of the core competencies of health professionals such as the Health Professionals Council of South Africa (Medical and Dental Professions Board of the HPCSA 2014) and the Australian Medical Council (Douglas et al. 2018). Thirdly, it may lead to limited or failure to evaluate the impact of HA training on graduates in the absence of specific learning outcomes or essential HA-related attitudes, knowledge skills identified as knowledge of community needs and the available community resources, policy-making knowledge and skills for public support, policymaker communication such as the writing of opinion pieces and editorials and public speaking, community campaigning for improving community and public health (Basu et al. 2017; Belkowitz et al. 2014; Hearne 2008). It is for these reasons, that formal incorporation of HA into the curricula in terms of explicit content, specific learning outcomes and associated assessment criteria is recommended.

Our findings revealed that HA was taught in a scaffolding and spiral approach from junior to senior years of the undergraduate curriculum. This is important for a number of reasons. Firstly, although the South African Health Professionals Regulatory body has identified HA as one of the core competencies required from the health professionals exiting the undergraduate health sciences programmes, the level at which HA should be taught or assessed has not been specified. Secondly, when operating from the premise that, to be a competent health advocate, "the health professional should responsibly use their expertise and influence to advocate with, and on behalf of, individuals, communities and populations to advance their health and wellbeing and build capacity for health promotion", it is clear that one has to first acquire some form of expertise in order to be considered a health advocate (Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons Canada 2005). However, introducing HA early in the programme helps to conscientise the students to the social and political health inequalities in their communities as an impetus for them to see how they can use the clinical knowledge and skills acquired throughout the training programme to later be able to influence and advocate for their patients or communities. Our findings showed that the spiral approach ensured that HA theory taught earlier and clinical expertise taught throughout the programme helped to horn students' health advocacy-related skills as demonstrated in their development and implementation of the health advocacy projects which were assessed in the senior and final years of training. The spiral approach also helped the academics to identify discipline-specific context and content that is necessary for students at appropriate level of training, thus ensuring that students develop and appreciate their role as health advocates within their own specific fields of study.

The assessment methods reported in our findings support the assessment of high cognitive skills and are much superior to the mere recall of information that is associated with traditional methods of assessment such as tests and written assignments. More importantly, is that our findings reported the assessment methods used to assess HA in the health sciences' programmes as similar to the principles identified by Lombardi (2007) as critical in authentic learning.

Lombardi (2007) argues that in authentic learning experiences should allow students to solve real-world problems and allow for peer-based evaluation where students are allowed to critique each other. For example, in our findings, it was reported that some students were placed in factories where they developed and implement advocated for factory workers. In some instances, students were allowed to critique their colleagues' projects as part of the assessment. Another important authentic assessment criterion identified in the assessment methods reported in our findings is that students were given ill-defined problems by allocating them in real world environments where the students had to identify problems that needed development and implementation of health advocacy projects over an extended period. Oral presentation of students' health advocacy projects implemented against such projects were then presented in slides for evaluation, thus supporting Lombardi's principle of ill-defined problem and students' immersion in the community to understand the community needs and develop and implement an appropriate project for suitable for assessment of learning while benefiting the community. The reported oral presentation in our findings shows that public speaking skills, an important skill in health advocacy is also assessed (Iucu and Marin 2014; Hearne 2008).

Including HA as a core competency in the training of health professions therefore has significant implications for the planning of health sciences curricula (Frank et al. 2010). The implications of HA within health professions training programmes in Africa include:

1. Improved graduate competencies;

2. Strengthened work readiness of graduates;

3. Students are better able to identify health challenges within communities and advocate for them; and

4. Improved health service development and delivery towards improved health of the population.

Ultimately, this means more effective higher education and training within health professions programmes in Africa.

The results of the study highlight the fact that, despite the barriers, the achievement of advocacy as a core outcome of health professions education is important. To this end, health advocacy competencies for both students and health professions educators are necessary (Tappe and Galer-Unti 2001) in order to effectively design teaching and learning activities as well as build health advocacy learning outcomes into training programmes.

There is therefore a call to address the dearth of health professionals who are competent through training in health advocacy and policy development for improving outcomes of public health initiatives was made by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) as early as 2003, in the USA (Hearne 2008). A similar call therefore needs to be made in South Africa, because of the prevailing health inequalities that require health professionals who are capable of advancing the public health agenda

LIMITATIONS

The study focused on the voices of the academic leaders and excluded the voices of students who are the direct recipients of health sciences education and training and other academics who are responsible for theoretical and clinical teaching in the programmes. The former could provide an insight into how they benefit from the teaching, learning and assessment approaches used to equip them with the HA competencies. The latter could provide insight into challenges experienced in the actual provision of HA content.

CONCLUSION

Our findings show that HA is considered as an important competency for health professionals in South Africa which is better taught in a spiral approach and when authentically assessed in the health sciences' undergraduate programmes. The barriers to full incorporation and promotion of HA into the health sciences' undergraduate curriculum should be addressed in order to produce health professionals who are competent health advocates for advancement of public health and in the interests of building capacity for health promotion. We recommend the inclusion of explicit HA-related learning outcomes and assessment criteria into all health sciences programmes for compliance with the standards set by both national and international health professionals' regulatory bodies.

REFERENCES

Basu, G., R. J. Pels, R. L. Stark, P. Jain, D. H. Bor, and D. McCormick. 2017. Training internal medicine residents in social medicine and research-based health advocacy: A novel in-depth curriculum. Academic Medicine, XX (X). doi 10.1097/ACM0000000000001580. [ Links ]

Belkowitz, J., L. M. Saunders, C. Zhang, G. Agarwal, D. Lichtstein, A. J. Mechaber, and E. K. Chung. 2014. "Teaching health advocacy to medical students: A comparison study." Journal of Public Health Management Practice 20(6): E10-9. Doi 10.1097/PPH.000000000000031. [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W. 2014. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 4th Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Dilshad, R. and M. Latif. 2013. "Focus Group Interview as a Tool For Qualitative Research: An Analysis." Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences 33(1): 191-198. [ Links ]

Douglas, A., D. Mak, C. Bulsara, D. Macey, and I. Samarawickrema. 2018. "The teaching and learning of health advocacy in an Australian medical school." International Journal of Medical Education 9: 26-34. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5a4b.6a15. [ Links ]

Eaton, M., M. deValpine, J. Sanford, J. Lee, L. Trull, and K. Smith. 2017. "Be the Change." Nurse Educator 42(5): 226-230. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000382. [ Links ]

Frank, J. R., L. S. Snell, O. Ten Cate, E. S. Holmboe, C. Carraccio, S. R. Swing, and K. A. Harris. 2010. "Competency-based medical education: Theory to practice." Medical Teacher 32(8): 638645. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190. [ Links ]

Friel, S. and M. G. Marmot. 2011. "Action on the Social Determinants of Health and Health Inequities Goes Global." Annual Review of Public Health 32(1): 225-236. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101220. [ Links ]

Health Professions Council of South Africa. 2014. Core competencies for undergraduate students in clinical assocaite, dentistry and medical teaching and learning programmes in South Africa. Pretoria: Health Professions Council of South Africa. [ Links ]

Hearne, S. A. 2008. "Practice-based teaching for health policy action and advocacy." Public Health Reports 123: 65-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549081230s209. [ Links ]

HPCSA see Health Professions Council of South Africa. [ Links ]

Hubinette, M., S. Dobson, I. Scott, and J. Sherbino. 2017. "Health advocacy*."Medical Teacher 39(2): 128-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1245853. [ Links ]

Iucu, R. B. and E. Martin. 2014. "Authentic learning in adult education." Procedia-Social & Behavioral Sciences 142: 410-415. [ Links ]

Knight, S., A. Ross, and O. Mahomed. 2017. "Developing primary health care and public health competencies in undergraduate medical students." South African Family Practice 59(3): 103-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2016.1272229. [ Links ]

Langins, M. and L. Borgermans. 2016. "Strengthening a competent health workforce for the provision of coordinated/ integrated health services." International Journal of Integrated Care 16(6): 231. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.2779. [ Links ]

Lombardi, B. M. 2007. "Authentic Learning for the 21st Century: An Overview." In Educause Learning Initiative (Vol. 1). http://alicechristie.org/classes/530/EduCause.pdf. [ Links ]

Medical and Dental Professions Board of the HPCSA. 2014. "Core competencies for undergraduate students in clinical associate, dentistry and medical teaching and learning programmes in South Africa." http://www.hpcsa.co.za/uploads/editor/UserFiles/downloads/medical_dental/MDB_Core_Competencies-ENGLISH-FINAL_2014.pdf. [ Links ]

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons Canada. 2005. "The CANMeds 2005 Physician Competency Framework." https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/canmeds-framework-e. (Accessed 27 October 2022). [ Links ]

Tappe, M. K. and R. A. Galer-Unti. 2001. "Health educators' role in promoting health literacy and advocacy for the 21st century." Journal of School Health 71(10): 477-482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb07284.x. [ Links ]

Van Heerden, B. B. 2012. "Effectively addressing the health needs of South Africa's population: The role of health professions education in the 21st century." South African Medical Journal 103(1): 21. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.6463. [ Links ]

Wong, L. P. 2008. "Focus group discussion: A tool for health and medical research." Singapore Medical Journal 49: 256-261. [ Links ]