Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Higher Education

versão On-line ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.36 no.5 Stellenbosch Nov. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/36-5-4661

GENERAL ARTICLES

Looking closely at what they say and what it tells us: experiences in a digital learning space

L. M. Khoza; K. van der Merwe

Department of Educational Technology, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This study explores lecturer and student experiences of using the Learning Management System (LMS) within a Faculty at a South African University. The results of the study highlight the extent to which lecturers and students engage with the LMS.

This article aims to determine the following: 1) the value that lecturers and students place on using the LMS as a platform to facilitate learning and teaching, 2) the typical resources, activities and assessments that lecturers and students place value on and why, and 3) to compare lecturer and student perspectives on the best utilization of the LMS.

Quantitative data were collected from the LMS and qualitative data collected from lecturers and undergraduate students through questionnaires and focus groups. A Social Constructivist framework was adopted as a lens for analysis of collected data. The results show resources are valued the most by both lecturers and students but the majority of students only access, on average, just more than half of the postings.

In terms of the constructs of the Social Constructivist framework, Learning and Connectedness showed positive responses, while improvement is necessary for Making Meaning and Agency.

Keywords: agency, connectedness, digital learning space, Learning Management System, making meaning, learning opportunities, value

BACKGROUND

The adoption of Learning Management Systems (LMSs) in higher education has seen researchers becoming more concerned with their usage (Ssekakubo, Suleman, and Marsden 2011; Mtebe 2015), satisfaction with the LMSs (Naveh, Tubin, and Pliskin 2012) and learning analytics (Prinsloo 2018; Veletsianos, Reich, and Pasquini 2016). It is, however, a concern that the usage of the LMSs shows that they are used for learning administration rather than for the improvement of student learning experiences (Koh and Kan 2020; Galanek, Gierdowski, and Brooks 2018). This concern is confirmed by the finding of Hustad and Arntzen (2013, 26) in which students and instructors considered the LMS being helpful in that it provides a centralised infrastructural facility for easy access to learning material rather than enhancement of student learning experiences.

Although studies have been conducted on LMS usage, not many studies have been conducted that incorporate LMS reports and student and lecturer experiences. This article contributes to the ongoing debate on the optimal use of an LMS. It seeks to establish lecturer and student experiences on the use of the LMS as a learning space. The article presents the results of qualitative data that have been collected through individual semi-structured interviews that were conducted with lecturers and focus groups with students. Quantitative data were collected from data automatically generated by the LMS and through a questionnaire that was completed by undergraduate students. Data were analysed through the lens of a Social Constructivist framework (McMahon et al. 2012, 131).

LITERATURE REVIEW

An analysis of literature on LMSs shows that the topics of educational data mining, LMS usage (Venter, Jansen van Rensburg, and Davis 2012; Mtebe 2015), satisfaction (Naveh, Tubin, and Pliskin 2012), attitudes (Govender and Rootman-le Grange 2015; Mkhize, Mtsweni, and Buthelezi 2016) and learning analytics (Mwalumbwe and Mtebe 2017; Prinsloo 2018) have received the greatest attention. However, utilisation of the LMS to facilitate the learning process appears to be under-researched (Sharpe et al. 2006; Laurillard 2012; Makhanya 2020).

An investigation of the use of WebCT from the student and lecturer perspective at Monash University reveals that students value the quality of well-designed and maintained courses, prompt feedback, while lecturers are concerned about the amount of time that they have to devote to designing quality online courses (Weaver, Spratt, and Nair 2008, 36). Kennedy, Hyland, and Ryan (2009, 4) define value as "making informed decisions on what students should learn". Salmon (2017) and Czerniewicz (2018) affirm Kennedy's definition by questioning whether there is any value in what lecturers teach and assess.

A similar study on the usage of the LMS was further conducted by Unwin et al. (2010, 17) in 25 African countries, in which LMSs have been found to be underutilised, due to infrastructural challenges, lack of training, lack of Open Educational Resources (OER), time constraints to develop OER, and lack of expertise to design quality online learning opportunities. A repeat study by Dube and Scott (2014, 104) revealed fear of the unknown and time constraints as the main reasons for the underutilisation of the LMS. Although contributing factors for the underutilisation of the LMS have been provided, it should be acknowledged that academics in African universities use learning technologies when convinced that it will enhance student performance (Czerniewicz 2018, 43).

It is concerning that an analysis of the usage of LMSs in Sub Saharan Africa, reveals that the usage of the LMS has not improved the quality of learning and teaching (Mtebe 2015, 56). National concerns on the value attached to the usage of the LMS has been emphasised by Venter et al. (2012, 184) who found that only 13 per cent of students enrolled for a Strategic Management Course at UNISA actively participated in discussion forums perform better. Conole (2012, 71) emphasises the value attached to collaboration, pointing out the importance of learning with and through others, emphasising co-creation of knowledge.

Govender and Rootman-le Grange's (2014, 230) study on the usage of the LMS found that both learners and teachers have very positive attitudes towards the LMS, pointing out that a positive attitude does not translate into the actual use of the LMS. Abrahams and Witbooi (2016) concur with this finding pointing out that lecturing staff prefer to use the LMS not only to make learning material available, because availability does not mean usage. Whetten (2007, 340) is of the same view arguing that usage does not mean students are actually learning, pointing out that "we should stop investing invaluable resources into teaching, because it does not always translate into learning". Hence Abrahams and Witbooi (2016) are of the opinion that availability of learning material should improve student learning experience by allowing more time for engagement with the learning material at their own time so that students are well prepared for obligatory class attendance. This is a probable explanation why Unwin et al. (2010, 21) recommend that training should go beyond the usage of LMSs and focus on instructional design and pedagogic practice. The significance of learning design is well-articulated by Whetten (2007, 341) in his article titled: Principles of effective course design: What I wish I had known about learning-centred teaching 30 years (20 years of teaching in management sciences and 10 years as director of a teaching and learning centre) advocating the following:

"I have come to understand that the most important things I can do to influence student learning involve carefully planning what my students - not their teacher - will do before, during, and after each class. In sum, I have learned that the most effective teachers focus their attention on course design" (Whetten 2007, 341).

Another study that gathered student, course coordinator, lecturer and educational technologist experiences on the usage of the LMS has been conducted by Snowball and Mostert (2010, 824) from Rhodes University, revealing that students are no longer keen to make their own notes, but become more dependent on the lecturers' notes and lecturers being concerned that students do not take ownership of their own learning. Snowball and Mostert's concern seem to be countered by a study conducted by Frith and Lloyd (2020, 84) at the University of Cape Town which shows an improvement in the quality of student engagement with learning material due to the availability of video lecture recordings in the LMS. Their study revealed that students are able to make their own notes by playing the recordings over and over specifically where complex concepts are discussed, particularly for those who do not have English as their home language.

The significance of class attendance has been established after 50 years of review of educational research as one of the seven principles for good practice in undergraduate student performance cannot be overemphasised (Chickering and Gamson 1987). A study conducted by Rossouw (2019) on student and lecturer perceptions on live streaming as a possible alternative to attend classes at Stellenbosch University, confirm the importance of class attendance. The study revealed that both first year Accounting students and their lecturers are of the opinion that lectures be recorded and be made available through the LMS for those who miss classes due to personal reasons such as clashes to engage with the material in their own time. Whetten (2007, 341) advocating for a learning centred approach, argues that class attendance adds value when grounded by "good design of what students do before, during and after class".

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Since the adoption of the LMS in 2014 by the faculty under study, our observations and interactions with lecturers show a significant investment in creating learning opportunities that are aimed at facilitating learning. This is evident from an audit of the usage of the LMS in 2018 which revealed that there was an 18 per cent increase in the number of modules that have been active on the LMS. It went from 39 per cent in 2015 to 90 per cent in 2020.

We were interested in determining the extent to which learning opportunities created on the LMS help students learn better (Race 2010). Conole (2012, 5) argues that the design of learning opportunities should be underpinned by appropriate support for students not to get confused and lost. It is envisaged that the lecturer's presence through lecturer-led, student-paced, collaborative, formative assessments and supportive activities (Carman 2005, 2), provided us with an opportunity to interrogate how the LMS is used as a learning space, that serves to include or exclude students from access to learning (Boughey 2012, 141). This begs the question of whether the usage of the LMS addresses student needs.

The primary research question of this study is to determine what lecturer and student experiences reveal about the usage of the LMS as a learning space. The following secondary questions will help us answer the main research question:

1. What does the current profile of the LMS look like in terms of lecturer usage and student engagement?

a. What is the frequency of postings by lecturers in terms of the resources, activities and assessments?

b. What is the level of student engagement with resources, activities and assessments?

2. What value do lecturers and students place on the usage of the LMS as a learning space?

a. What are the lecturer and student perspectives on, and experiences of the use of the LMS?

b. Why do lecturers and students place value on specific resources, activities and assessments?

3. Which of the four constructs in the Social Constructivist Theory are best represented and which are not?

a. What does this mean for future development of the LMS?

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In the present study, data analysis is underpinned by a Social Constructivist Theory, as adapted by McMahon et al. (2012). This framework allowed us to engage in thoughtful reflection on the experiences as seen through the lenses of the participants (McMahon et al. 2012, 131). The diagram below presents the four facets of the Social Constructivist Theory.

We conducted this study as a way of reflecting on the usage of the LMS as a digital learning space from shortly after the bedding phase (i.e., the early years of implementation) to the mature phase (i.e., the later years) (Strydom 2015, 15). According to the framework, our interpretation of collected data was guided by the four overlapping constructs as outlined in Figure 1. In the context of this study, the constructs are interpreted as follows:

1. Connectedness: This refers to the effect of the contextual location of participants, opportunities and constraints they face in connecting with others via the LMS.

2. Meaning making: This addresses the participants' understanding and experiences in orientating themselves within the virtual classroom.

3. Learning: Learning is the most self-explanatory construct concerning the students' learning experiences. This is how the student "moves between action, to reflection, to new thinking, to planning and then back to action" (McMahon et al. 2012).

4. Agency: This construct refers to the extent to which ownership and responsibility is experienced in using the LMS as a learning space (McMahon et al. 2012, 132).

METHODOLOGY

The present study is classified as a case study involving an in-depth description and analysis of data from the LMS reports, lecturer and student experiences through questionnaire and interviews for the period of 2018 to 2020.1 A mixed-method approach was employed (Plowright 2012), because this method "builds on the synergy, strength and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative data as we explore lecturer and student experiences in what it means to use the LMS as a learning and teaching space" (Williams 2007, 70). Four instruments have been used for data collection. 1) Semi-structured interviews: Qualitative data were collected through individual semi-structured interviews conducted with lecturers and focus groups with students. Lecturers were interviewed from August 2018 to October 2018. 2) Nine semi-structured focus groups were conducted with undergraduate students in November 2018, September 2019, October 2019 and January 2020. Interviews were audio-recorded. 3) Quantitative data were collected through a questionnaire that has been completed by undergraduate students. 4) Quantitative data were also collected from reports generated by the LMS of the undergraduate modules and were collected in October 2019 and November 2020.

DATA ANALYSIS

For this study, qualitative data were thematically analysed. Thematic analyses are relevant in the present study because it is a "method that is used to systematically identify, organise and offer insight into patterns of meaning across a data set" (Braun and Clark 2012, 57). The themes evident in the transcripts of the interviews were coded according to the four constructs in McMahon et al. (2012) Social Constructionist framework. Interpretations were cross-checked by the authors to reach consistency and agreement.

Reports from the LMS were pulled and analysed according to the type and number of postings per module. This was done for 22 (n=22) semester 1 modules and 24 (n=24) semester 2 modules which totals to 138 (n=138) modules over six semesters across three years, spanning from 2018 to 2020. The type of posting was categorized into three types: resources, activities and assessments. Examples of postings that are classified as resources are PowerPoints, lecture notes, readings, and videos and audio files. Examples of activities are discussion forums or any type of posting which requires active engagement. From the student perspective, engagement involves "how they study and they do activities on their own (individually or as a group), activities that require writing papers for the course and fellow students, the amount of time they spend on a task and the intellectual challenge the task requires" (Whetten 2007, 351). Examples of assessments in this study include all forms of "tests" including quizzes and assignments, both formative and summative. These quantitative data were analysed and are presented as percentages in tables and graphs. Ethical clearance was obtained for the study and informed consent obtained from the participants. Participation in the study was voluntary.

Participants

Purposive sampling was employed for this study. Lecturers from the five programmes offered at the Faculty, who teach at the undergraduate level, were invited to participate in the study. Five lecturers who use the LMS in all modules, four lecturers who use the LMS in some modules, two of those who used the LMS when it was adopted in 2014, but became inactive or stopped using the LMS and one of those who never used the LMS were interviewed.

In total 159 (n=159) student participants took part in this study. Ninety-two (n=92) were residential students and 67 (n=67) were Telematic Education (TE) (i.e., distance learning) students. Twenty-eight (n=28) residential students and 23 (n=23) TE students took an online survey with closed and open-ended questions. Sixty-four (n=64) residential students took part in four focus group sessions while 44 (n=44) TE students took part in three focus group sessions.

The Faculty has both Residential and Telematic Education (TE) (i.e., distance learning) students as a permanent arrangement. Both groups are loaded to the same modules on the LMS. All undergraduate students from both groups were invited to partake in this study.

RESULTS

General

Table 1 indicates the results from the reports pulled from the LMS.

There was an average of 44 (n=44) students and an average of 47 (n=47) postings per module. The findings revealed that the average amount of material on the modules engaged with by 50 per cent and more of the users was 54 per cent.

The average number of postings

Figure 2 shows the average number of postings across years and semesters. This is important to see the extent of the use of the LMS by lecturers.

Engagement with postings

Figure 3 illustrates the average percentage of the users who accessed more than 50 per cent of the postings.

Rating of the helpfulness of online modules

Type of material posted and accessed

Figure 4 shows the proportion of postings of resources, activities and assessments uploaded to the LMS by lecturers.

Of the material posted, 73 per cent of the postings were resources, with assessments at 17 per cent and activities at 10 per cent. Of these, overall, 50 per cent and more of the users accessed 65 per cent of the resources, 21 per cent of the assessments and 15 per cent of the activities. Figure 5 illustrates what percentage of each type of posting (resources, activities or assessments) were accessed by more than 50 per cent of the users across the years.

Figure 6 shows the percentage of students that rated their online modules as helpful.

In the online survey conducted with 28 (n=28) Residential students and 23 (n=23) TE students, 93 per cent of Residential students rated the online modules as helpful while only 78 per cent of the TE students rated the same modules as helpful.

Focus groups

Figure 7 shows the percentage of positive and negative comments related to the four Social Constructivist constructs for both the Residential and TE students.

In terms of the four Social Constructivist constructs, the majority of the feedback for both groups of students naturally focused on Learning that scored the highest for both positive and negative comments, with the positive comments exceeding the negative ones for the Residential and TE groups. Negative comments, however, outweighed the positive comments for both Making meaning and Agency, with the biggest discrepancy in scores for positive and negative comments for Making meaning, for both groups.

Lecturer interviews

Themes from the lecturer interviews were divided into neutral, positive and negative comments. The themes which emerged from the data were discussions on resources, activities and assessments, reflection on practices, learning design, data mining/learning analytics, challenges students experience, reason for non-usage of the LMS, and further development and support concerning online learning material and the use of the LMS. The graphs below show the number of comments per theme in descending order and the number of negative comments per category.

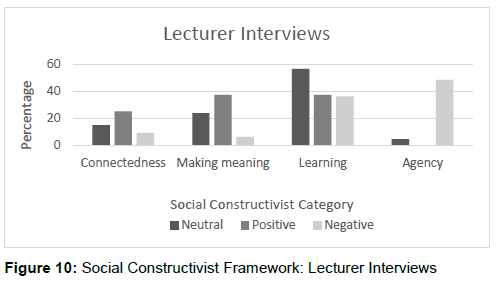

Figure 10 shows the results of the lecturer interviews coded according to the four Social Constructivist constructs.

Findings showed that the majority of the positive comments were made regarding Learning and Making Meaning, with the highest number of negative comments for Agency. Comments regarding Agency predominantly had to do with concerns about student agency in learning as reported in other literature.

DISCUSSION

Engagement with postings

Findings show that across all semesters, on average, only 54 per cent of the material posted was engaged with by 50 to 100 per cent of the users. There is however an increase of 9 per cent in user engagement from semester 1 of 2018 to semester 2 of 2020. But the percentages remain within the 50s over the three-year period. The fact that students are engaging with just more than half the material posted would indicate that most of the postings are non-compulsory, that the LMS is used primarily as a repository and the material is largely supporting or supplementary material.

The average number of postings

There was an increase of 18 posts on average from semester 1 of 2018 to semester 2 of 2020 indicating more use of the LMS on the lecturers' part over the period of time. There is a trend which shows that postings for second semester modules remain slightly below that of first semester modules. The reasons for this are unclear.

Type of material posted and accessed

It is not unexpected that resources constituted the biggest proportion of postings since the primary function of an LMS is often viewed as a repository. This was followed by assessments and activities. One might have expected 100 per cent access to assessments but since this is not the case it indicates that not all assessments are compulsory or for marks, some are practice assessments, or examples and many assessments for both Residential and TE students still take place in person. The highest percentage of resources accessed was for semester 2 of 2020 with an increase of 11 per cent from semester 1 of 2018 to semester 2 of 2020 in terms of engagement with resources. Engagement with activities and assessments do not mimic a similar trend and show a fluctuation in percentages across the semesters.

Rating of the helpfulness of online modules

It would seem that the current design of the modules is better suited to a blended learning approach rather than TE, distance learning, given the significantly higher rating of the "helpfulness" of the modules from the Residential group.

Focus groups: Students

Many positive comments centred on the theme of Learning, especially the provision of resources, but comments also highlighted the overwhelming number of resources and the lack of differentiation between which resources are important and which are supplementary. Such comments fell within the Making Meaning construct that constituted the highest percentage of negative comments.

Table 2 provides some brief examples per construct of both positive and negative comments provided in the focus groups.

Interviews: Lecturers

The majority of negative comments fell under the theme of "reflection on practices". This theme concerned reflection on the use of the LMS and, in the lecturers' opinion, according to observations of the students' engagements and responses, what works and what does not. It was apparent that the lecturers were aware that not all postings were accessed and wondered how their time can be better spent than creating resources that are underutilised.

CONCLUSIONS

It is apparent that resources are valued the most by both lecturers and students, but the majority of students are only accessing, on average, just more than half of what is posted. Students have a particular preference for audio-visual material. Students are of the opinion that learning material, in particular, audio-video files act as a guide to delve deeper into building their own knowledge (Conole et al. 2004, 24). Matarirano et al. (2021) too found low utilisation of the LMS by students at Walter Sisulu University. Their findings show that students preferred visual material. Frith and Llyod (2020) confirm the value attached to visual material pointing out that lecture video recordings made available through the Learning Management System improves quality learning of Mathematics and Quantitative Literacy for Engineering and Law first year students of the University of Cape Town respectively. Availability of lecture recordings is assumed to be self-regulated learning (Frith and Lloyd 2020).

Students appreciate the provision of material that supports their learning but appreciate when lecturers distinguish between compulsory and supplementary material. Bawa (2020, 5) also points out that students become overwhelmed by the amount of content provided in the online learning and teaching space. Assessments, particularly quizzes were the second most valued posting, followed by activities.

In terms of the four Social Constructionist constructs, the findings show that students, overall, had more positive reports on their experiences of Learning and Connectedness. For the Making Meaning and Agency constructs, the negative comments surpassed the positive ones. This indicates a need to improve the design of the modules, the set-up of the virtual classroom and the narrative that directs the learning.

It is recommended that faculties conduct such a study on the use of their LMS to better understand how it is being used and how its use could be improved, but most importantly not only enhance but transform student learning experience and provide lecturers with adequate support (Conole et al. 2004, 21). These findings can inform and direct decisions for better learning experiences. After these factors have received sufficient attention, a repeat of the study can be conducted to ensure that meaningful change is effected by this research.

SIGNIFICANCE AND IMPLICATIONS OF THE CURRENT STUDY

The value of such a study is viewed as three-fold. Firstly, conducting an audit of postings on an LMS is not simply an administrative counting exercise, but the task allows for an opportunity to understand current practices. Secondly, analysis of the quantitative data combined with the qualitative data from the focus groups and interviews, helps to determine the appreciation of those practices and whether they should be revised or not. In addition to this, data from the interviews with lecturers were able to identify where lecturer support is needed regarding the use of the LMS. Thirdly, adopting a Social Constructionist Framework provided ideal constructs for analysis to home in on four key and important aspects of teaching and learning.

Social Constructionist Frameworks place much emphasis on student engagement (Sthapornnanon et al. 2009, 1). If educators are aiming to enhance learning experiences and motivation and in addition simulate a comparable experience of learning in the online space to that of a contact classroom, then it is of value to apply a Social Constructionist Framework to their research. This will assist with enhancing optimal use of, and engagement on an LMS. The four constructs of the framework used in this study, namely, Connectedness, Making Meaning, Learning and Agency allow for analysis of students' engagement and a means to gauge autonomy in their learning. Creating maximum engagement with content, classmates and lecturers on an LMS should be the goal as this enhances motivation to learn (Martin and Bolliger 2018, 205).

There are several implications of LMSs for higher education. As Rhode et al. (2017, 68) point out, an LMSs is a critical tool for all higher education institutions. An LMS is not only a vital vehicle for teaching and learning but a platform to discover teaching and learning behaviours and preferences. It is therefore a valuable space for research. By exploring student and lecturer experience of using the LMS, we uncovered that the quality of design of learning opportunities determines the extent to which student learning is facilitated.

Conole (2012) argues that learning is facilitated by creating opportunities for students to "learn with and through others". In this way, the use of the LMS not only helps "making content available for students but helps uncover learning material with students" (Smith et al. 2005, 88). The challenge, as identified by Conole (2012), is to capitalise on the capabilities of the LMS and create reflective opportunities for students to critically critique and engage in conversations with peers and lecturers (Conole 2012). In this way, students become actively involved in knowledge construction.

Boughey (2012, 144) states that "Learning and knowledge construction however depends on the use of the LMS as a social space that ensures that learning and teaching is contextualised". With the importance of the "social space" in mind, this study shows that the application of McMahon et al.'s (2012) Social constructivist theory is able to advance our understanding, knowledge and interpretation of practice regarding the use of the LMS. The framework of this Social constructivist theory provided suitable parameters to assist in investigating the research questions of this study.

The findings of this study have important implications for practice and theory, particularly in an African context. Generally speaking, educators and learners located in contexts, like some African regions, where there are challenges concerning internet connectivity, infrastructure, computer literacy and budget, face a different experience of learning design and studying than educators and students from elsewhere (Kigotho 2021). The use of LMSs, particularly in Africa should not only improve access to resources, activities and assessments, but address "equity, diversity, inclusion, retention and completion" (Houlden and Veletsianos 2019, 1011). This article shows that learning design as an iterative process should be underpinned by empathy, particularly in Africa, and that contextualised solutions are required (Gachago and Cupido 2020). Higher education theory is advanced by our study in that our findings enrich an understanding of "connectedness". This is shown through the value and application of the "pedagogy of care" in teaching philosophy and learning design (Bali 2020), because design is a medium for building a relationship and supporting learning optimally (Morris 2021).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all student and staff who participated in this research as well as Mr Rabe for his assistance with data collection.

NOTE

1 The faculty did not resort to fully online teaching during Covid and continued with contact classes. The impact of Covid on higher education is therefore not discussed.

REFERENCE LIST

Abrahams, Mark A. and Sarah Witbooi. 2016. "A realist assessment of the implementation of blended learning in a South African higher education context." South African Journal of Higher Education 30(2): 13-30. https://doi.org/10.20853/30-2-577. [ Links ]

Bali, Maha. 2020. "Level of care and Intentional equity". Pedagogy of care (blog), 28 May 2020. https://blog.mahabali.me/educational-technology-2/pedagogy-of-care-covid-19-edition/. [ Links ]

Bawa, Papia. 2020. "Learning in the age of SARS-COV-2: A quantitative study of learners' performance in the age of emergency remote teaching." Computers and Education Open 2020(1). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7649631/. [ Links ]

Boughey, Chrissie. 2012. "Social Inclusion and Exclusion in a Changing Higher Education Environment." Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research 2(2): 133-151. http://dx.doi.org10.4471/remie.2012.07. [ Links ]

Braun, Virginia and Victoria Clarke. 2012. "Thematic analysis." In The Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, ed. H. Cooper, 57-71. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Carman, Jared M. 2005. "Blended learning design: Five key ingredients." Agilent Learning, 1-11. https://www.it.iitb.ac.in/~s1000brains/rswork/dokuwiki/media/5_ingredientsofblended_learning_design.pdf. [ Links ]

Chickering, Arthur W. and Zelda F. Gamson. 1987. "Seven Principles for good education in undergraduate education." AAHE Bulletin 3(7): 1-6. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED282491.pdf. [ Links ]

Conole, Grainne. 2012. Designing for learning in an open world. Springer e-Books. [ Links ]

Conole, Grainne, Martin Dyke, Martin Oliver, and Jane Seal. 2004. "Mapping pedagogy and tools for effective learning design." Computers & Education 43(1-2): 17-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2003.12.018. [ Links ]

Czerniewicz, Laura. 2018. "Inequality as higher education goes online." In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Networked Learning, 38-46. Springer, Cham. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fss/organisations/netlc/abstracts/pdf/S2Paper4.pdf. [ Links ]

Dube, Sibusisiwe and Elsje Scott. 2014. "An empirical study on the use of the Sakai Learning Management System (LMS): Case of NUST, Zimbabwe." In Proceedings of the e-skills for Knowledge Production and Innovation Conference, 101-107. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sibusisiwe_Dube/publication/281585795_An_Empirical_Study_on_the_Use_of_the_Sakai_Learning_Management_System_LMS_Case_of_NUST_Zimbabwe/links/55eebcb408aedecb68fcb5ad/An-Empirical-Study-on-the-Use-of-the-Sakai-Learning-Management-System-LMS-Case-of-NUST-Zimbabwe.pdf. [ Links ]

Frith, Vera and Phamela Lloyd. 2020. "Student practices in use of lecture recordings in two first-year courses: Pointers for teaching and learning." South African Journal of Higher Education 34(6): 65-86. https://doi.org/10.20853/34-6-3863. [ Links ]

Gachago, Daniela and Xena Cupido. 2020. "Designing learning in unsettling times." http://heltasa.org.za/designinglearning-in-unsettling-times/. [ Links ]

Galanek, Joseph D., Dana C. Gierdowski, and D. Christopher Brooks. 2018. "ECAR study of undergraduate students and information technology." Research Report Louisville no. 12. https://library.educause.edu/~/media/files/library/2018/10/studentitstudy2018.pdf?la=en. [ Links ]

Govender, Indren and Ilze Rootman-le Grange. 2015. "Evaluating the early adoption of Moodle at a higher education institution." In European Conference on e-Learning, 230-238. Academic Conferences International Limited. [ Links ]

Houlden, Shandell and George Veletsianos. 2019. "A posthumanist critique of flexible online learning and its 'anytime anyplace' claims." British Journal of Educational Technology 50(3): 1005-1018. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12779. [ Links ]

Hustad, Eli and Aurèlie Aurilla Bechina Arntzen. 2013. "Facilitating teaching and learning capabilities in social learning management systems: Challenges, issues, and implications for design." Journal of Integrated Design and Process Science 17(1): 17-35. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eli_Hustad/publication/262220843_Facilitating_Teaching_and_Learning_Capabilities_in_Social_Learning_Management_Systems_Challenges_Issues_and_Implications_for_Design/links/56091c6508ae840a08d35ac5.pdf. [ Links ]

Kennedy, Declan, Áine Hyland, and Norma Ryan. 2009. "Learning outcomes and competences. Introducing Bologna Objectives and Tools." Science Education International 23(3): 1-18. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Declan_Kennedy2/publication/285264101_Learning_outcomes_and_competencies/links/5a378ac7a6fdcc769fd82f3c/Learning-outcomes-and-competencies.pdf. [ Links ]

Kigotho, Wachira. 2021. "Narrowing Africa's Digital Divide in Education." Higher Education and Research in Africa. https://www.carnegie.org/topics/topic-articles/african-academics/narrowing-africa-digital-divide-education/. [ Links ]

Koh, Joyce Hwee Ling and Rebecca Yen Pei Kan. 2020. "Students' use of learning management systems and desired e-learning experiences: Are they ready for next generation digital learning environments?" Higher Education Research & Development: 1 -16. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/07294360.2020.1799949?casa_token=nJLi2dnOyfkAAAAA:Pk7-xfHu05_erbR76gR6JG18ZdxJWlYCYxMNUQ91mJHX0Xce_O0Wlkf736XP95VvdIq7h_cZiIEiRg. [ Links ]

Laurillard, Diana. 2012. Teaching as a design Science: Building pedagogical patterns for learning and Technology. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Makhanya, Mandla. 2020. "This is the time for universities to make blended learning a strategic dimension for their future." 19th European Conference on e-Learning, 28-30 October 2020, University of Applied Sciences, Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (HTW) Berlin, Germany. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03069885.2011.646949?casa_token=JLF2rsPDbDQAAAAA:ECi_0kvaSnhuS4a89XtT5s-I-g6sbZj8rvJHyda9yoiKR7dP4TM4lMlnxlGVb-rGJJ3McR_J8AgL1w. [ Links ]

Martin, Florence and Doris Bolliger. 2018. "Engagement Matters: Student Perceptions on the Importance of Engagement Strategies in the Online Learning Environment Online Learning." Online Learning Journal 22(1): 205-222. [ Links ]

Matarirano, Obert, Manoj Panicker, Norber Jere, and Afika Maliwa. 2021. "External factors affecting blackboard learning management system adoption by students: Evidence from a historically disadvantaged higher education institution in South Africa." South African Journal of Higher Education 35(2): 188-206. https://doi.org/10.20853/35-2-4025. [ Links ]

McMahon, Mary, Mark Watson, Candice Chetty, and Christopher Norman Hoelson. 2012. "Examining process constructs of narrative career counselling: An exploratory case study." British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 40(2): 127-141. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03069885.2011.646949?casa_token=B8H8IF2xAIEAAAAA:MezfP0zp36An4uBa5khtZC5_A6IEoI5878uwasJp1B606vX6inSpYeo0BjDkesWj7JuljeGq0TdS0w. [ Links ]

Mkhize, Peter, Emmanuel Samuel Mtsweni, and Portia Buthelezi. 2016. "Diffusion of innovations approach to the evaluation of learning management system usage in an open distance learning institution." International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 17(3): 295-312. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/irrodl/1900-v1-n1-irrodl05024/1066237ar.pdf. [ Links ]

Morris, Sean. 2021. "A problem-posing learning design." Twitter post, 15 January 2021. https://www.seanmichaelmorris.com/problem-posing-learning-design/. [ Links ]

Mtebe, Joel. 2015. "Learning Management System success: Increasing Learning Management System usage in higher education in sub-Saharan Africa." International Journal of Education and Development using ICT 11(2): 51-64. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/151846/article_151846.pdf. [ Links ]

Mwalumbwe, Imani and Joel S. Mtebe. 2017. "Using learning analytics to predict students' performance in Moodle learning management system: A case of Mbeya University of Science and Technology." The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 79(1): 113. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2017.tb00577.x. [ Links ]

Naveh, Gali, Tubin Dorit, and Pliskin Nava. 2012. "Student Satisfaction with Learning Management Systems: A lens of critical success factors." Technology Pedagogy and Education 21(3): 337-350. DOI10.1080/1475939X.2012.720413. [ Links ]

Plowright, David. 2012. Using mixed methods: Frames for and Integrated Methodology. London: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Paul. 2018. "Using student data: Moving beyond data and privacy protection to student data sovereignty as a basis for an ethics of care." In 13th International Conference on e-Learning Proceedings, ed. E. Ivala. 5-6 July 2018, Cape Peninsula University of Technology: South Africa. https://tinyurl.com/ICEL2018. [ Links ]

Race, Phil. 2010. "Ripples model of seven factors underpinning successful learning." Assessment, Teaching & Learning Journal 8: 27-29. [ Links ]

Rhode, Jason, Stephanie Richter, Peter Gowen, Tracey Miller, and Cameron Wills. 2017. "Understanding faculty use of the learning management system." Online Learning 21(3): 68-86. doi: 10.24059/olj.v%vi%i.1217. [ Links ]

Rossouw, Mareli. 2019. "The perceptions of students and lecturers on the live streaming of lectures as an alternative to attending class." South African Journal of Higher Education 32(5): 253-269. https://doi.org/10.20853/32-5-2696. [ Links ]

Salmon, Gilly. 2017. "Carpe Diem Learning Design: Preparation and Workshop". Class notes. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University. 17 May 2017. [ Links ]

Sharpe, Rhona, Greg Benfield, George Roberts, and Richard Francis. 2006. "The undergraduate experience of blended e-learning: A review of UK literature and practice." The Higher Education Academy: 1-103: https://www.academia.edu/download/30922035/Sharpe_Benfield_Roberts_Francis.pdf. [ Links ]

Smith, Karl A., Sheri D. Sheppard, David W. Johnson, and Roger T. Johnson. 2005. "Pedagogies of engagement: Classroom-based practices." Journal of Engineering Education 94(1): 87-101. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2005.tb00831.x. [ Links ]

Snowball, Jen and Markus Mostert. 2010. "Introducing a learning management system in a large first year class: Impact on lecturers and students." South African Journal of Higher Education 24(5): 818-831. https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC37639. [ Links ]

Ssekakubo, Grace, Hussein Suleman, and Gary Marsden. 2011. "Issues of adoption: Have e-learning management systems fulfilled their potential in developing countries?" In ACM International Conference Series, 231-238. Paper delivered at the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists Conference on Knowledge, Innovation and Leadership in a Diverse, Multidisciplinary Environment. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/2072221.2072248?casa_token=4v53DkFSHQ4AAAAA:Hw-GOojpb_byNDLoUoM7ZZ1X-4nwhE-U9j95Jb4EbyEefo4rwBhCvkOjVqND-fu7-S0OXpoEI2k1jQ. [ Links ]

Sthapornnanon, Nunthaluxna, Rungpetch Sakulbumrungsil, Anuchai Theeraroungchaisri, and Suntaree Watcharadamrongkun. 2009. "Social Constructivist Learning Environment in an Online Professional Practice Course." American Journal of Pharmacutical Education 19(73): 1-10. http://www.ncvi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2690880. [ Links ]

Strydom, Sonja. 2015. "Renewal of targeted Academic Programmes." Learning Technolgies Report. Stellenbosch University, 12 April 2015. [ Links ]

Unwin, Tim, Beate Kleessen, David Hollow, James B. Williams, Leonard Mware Oloo, John Alwala, Inocente Mutimucuio, Feliciana Eduardo, and Xavier Muianga. 2010. "Digital learning management systems in Africa: Myths and realities." Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance ande-Learning 25(1): 5-23. DOI: 10.1080/02680510903482033. [ Links ]

Veletsianos, George, Justin Reich, and Laura A. Pasquini. 2016. "The life between big data log events: Learners' strategies to overcome challenges in MOOCs." AERA Open 2(3): 1-10. http://ero.sagepub.com. [ Links ]

Venter, Peet, Mari Jansen van Rensburg, and Annemari Davis. 2012. "Drivers of Learning Management System use in a South African open and distance learning institution." Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 28(2): 183-198. https://ajet.org.au/index.php/AJET/article/download/868/146. [ Links ]

Weaver, Debbi, Christine Spratt, and Chenicheri Sid Nair. 2008. "Academic and student use of a learning management system: Implications for quality." Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 24(1): 30-41. https://ajet.org.au/index.php/AJET/article/download/1228/453/. [ Links ]

Whetten, David A. 2007. "Principles of effective course design: What I wish I had known about learning-centered teaching 30 years ago." Journal of Management Education 31(3): 339-357. [ Links ]

Williams, Carrie. 2007. "Research Method." Journal of Business & Economic Research 5(3): 65-72. https://clutejournals.com/index.php/JBER/article/download/2532/2578. [ Links ]