Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.36 n.4 Stellenbosch Sep. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/36-4-5191

GENERAL ARTICLES

Postgraduate pedagogy in pandemic times: online forums as facilitators of access to dialogic interaction and scholarly voices

B. MendelowitzI; I. FoucheII; Y. ReedIII; G. AndrewsIV; F. Vally EssaV

IWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1915-2154

IIWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4562-4944

IIIWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6157-3449

IVWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5268-0800

VWits School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3255-7199

ABSTRACT

In 2020, when the switch to remote teaching and learning required redesigning asynchronous online versions of face-to-face courses, we were concerned about whether access to engaged and dialogic learning could be facilitated in this new space. In attempting to address this concern we asked students in a BEd Honours course to post, in an online forum, their reflective responses to weekly readings and to each other's posts. This discussion forum became the engine of the course. With their permission, the posts of students in the 2021 cohort, together with their summative reflective reading response assignment, were analysed in order to understand different kinds of dialogic interactions and their affordances for reducing the potential alienation of asynchronous learning. One of the key findings that emerged from this analysis is the role of dialogic interaction in facilitating the development of personal, professional and scholarly voices which contributed to epistemic access. Our analysis was informed by the theoretical work of Bakhtin on the dialogic and by theoretical and empirical work of scholars in the field of critical pedagogies. We use examples from the writing of a "stronger" and a "weaker" student to illustrate how students negotiated roles and positions for themselves by appropriating and using the textual resources available on the forum. We argue for the value of sustained practice in "writing about reading", of reading each other's writing and of "writing back" to one another on-line, for the gradual acquisition of a range of confident voices and for enhanced understanding of module content.

Keywords: dialogic, scholarly voices, reflexivity, multivoicedness, epistemic access, online pedagogy, postgraduate pedagogy

INTRODUCTION

Extensive twenty-first century scholarship in the field of post-graduate pedagogies has focused almost exclusively on aspects of research supervision, much of it at doctoral level (e.g. Badenhorst and Guerin 2015; Kiley 2015; Rule, Bitzer, and Frick 2021). Little attention has been given to teaching and learning in the course work that is a significant component of Honours degrees and of some Masters and doctoral degrees. In the even more extensive scholarship on the pedagogies of distance education and of online learning, researchers generally assume that pedagogies for postgraduate courses have been carefully planned into overall course and programme design and that postgraduate students know how to be self-directed learners. In this article we offer a critically reflective account of what we learned from "a sudden move" (Feldman 2020) in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, from face-to-face to on-line teaching and learning in a B Ed Honours course. We argue that the findings of this study have important implications for postgraduate pedagogy and for the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Before 2020, Language and Literacy, Theory and Practices (LLTP) had been offered only in contact mode in the University of the Witwatersrand's B Ed Honours programme. With the swift changes necessitated by the pandemic and with our university strongly discouraging synchronous sessions because of the socio-economic and infrastructural realities of the South African landscape, one of our greatest concerns was how to reconfigure the course in an asynchronous teaching and learning environment. How could we facilitate optimal student participation and access to knowledges without the in-class discussions of lecture content and course readings that had been the engine of the course? We made two decisions: (i) to make online forum posts the new course engine and (ii) to investigate possible affordances and limitations of these dialogic posts for student learning and for the development of scholarly voice. The forum posts took two forms: firstly, each student's individual response to weekly course readings and secondly, discussions among students and between students and lecturers in response to the individual postings.

We argue that online forums, focused on students' responses to prescribed texts, are more conducive to engaged dialogic interaction with texts and with one another than had been the case in the face-to face iterations of the course for the majority of students. The forum discussions became a place for them to experiment, to play, and to try out different voices. Doing so enabled levels of engagement, insightful reflection and a learning trajectory that we had not previously experienced.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

There has been much theorising of the dialogic in literacy and language teaching and learning (Freire 2005; Bakhtin 1981), together with scholarship on the implementation of critical dialogic pedagogies in a range of contexts (Jesson, Parr, and McNaughton 2013; Mendelowitz, Ferreira and Dixon forthcoming). We want to contribution to this scholarship both theoretically and empirically. We are particularly interested in student engagement in different kinds of critical dialogic interactions. We want to know if such interactions can reduce the potential alienation of asynchronous learning and contribute towards creating a community of learners online. Building on Freire (2005), we conceptualise dialogism as follows:

"Dialogism extends way beyond a conversation between two or more people. It refers to multiple dynamic interactions with the self, with others and with texts and cultural resources" (Mendelowitz et al. forthcoming).

In the context of the LLTP course forum we focus on four important aspects of the dialogic: dialogic and audience (self and other), reflexivity, multivoicedness and texts / cultural resources. We see all four aspects operating in this course and in the forum data. What we want to uncover is how these processes unfolded, roles that different actors played and the extent to which this critical dialogic approach enabled equitable access for students despite the difficult pandemic conditions.

Dialogic and reflexivity

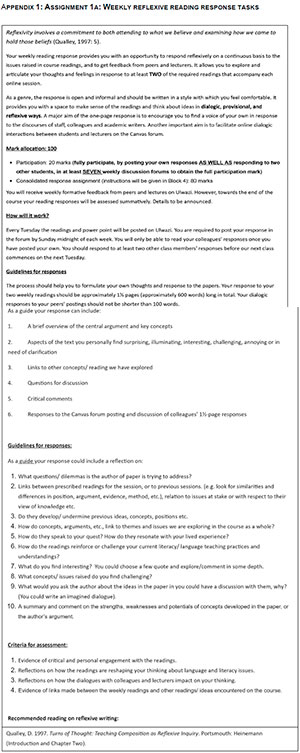

One important aspect of the dialogic process is dialogues with the self and how these are reshaped by dialogues with others and textual/cultural resources. As explained by Bradbury (2019) from a Vygotskian perspective in relation to narrative, the self is a significant element of audience in this dialogic process. The narrating self becomes both subject of the story and object of reflection and analysis, enabling one to see the self as other, through one's own eyes and the eyes of others. Bradbury (2019, 23) concludes that these inner conversations "enable new relations with the world, possibilities to imagine alternatives and transform the present parameters of our situation". In the context of the weekly reflexive reading response tasks (see Appendix 1), which are a hybrid personal/academic genre with narrative elements, the writer is sharing thoughts and responses to weekly readings - and at times makes connections to stories from personal experience. There is considerable evidence in the data of how, through this process, the students began to re-think, re-imagine, critically interrogate their ideas and apply them to their lives, their studies (emerging scholarly identities) and their teaching contexts.

Dialogic and audience (self and other)

Audience is an important part of the dialogic. Dialogues are always directed to someone (addressivity) and the nature (content, tone, what can and cannot be said) of a dialogue is shaped by how the speaker imagines the addressee (Bakhtin 1986, 95) and the power relations. Hence, one cannot assume that an audience for writing is always enabling. There is evidence of play and trying on different voices and discourses in the forum but within the discursive constraints that writing for any audience evokes. Students are aware that participation in the forum constitutes a performance for self, peers and lecturers in an academic space. It would be naïve to think of this as an entirely free space to play with ideas and voices. Also, the asynchronous online dialogue is in some ways a strange dialogue - dialogue in writing among people who have never met face to face and who cannot gauge audience response by reading body language.

Despite these limitations, audience plays a significant role in this dialogic process, giving students a sense of how their ideas have travelled and how others make sense of their ideas (or not). It is also important to keep in mind that students take on different roles in relation to audience. They have an audience for their work, and function as audiences for the weekly reflexive reading response tasks of other students, as well as audience for their own writing.

Dialogic and multivoicedness

Voice is the thread that weaves all the aspects of dialogic engagement together. Drawing on Bakhtin, we conceptualise voice as dialogic and multiple. Each individual voice draws on other voices from the past, present or imagined future. This notion of voice emerges from Bakhtin's (1981) conceptualisation of language as heteroglossic, always a site of struggle that traverses the individual and the social. In relation to the LLTP course, the weekly reflexive reading response tasks and the summative reflexive reading response assignment, students are both engaging with the concept of heteroglossic language and trying out different voices in relation to self and other.

Thesen (2014) illustrates how voice and audience are inextricably connected through her argument that voice is not only located in the text but also at the point of reception, for the reader. We write to make a point, to be heard. We want our voices to carry ideas across spaces and to reach receptive readers with whom we establish a relationship. From this perspective, voice has a journey, from the point of construction on the written page to the point of reception.

A fundamental aspect of this journey is voice as "writer agency across space" (Thesen 2014, 3).

Dialogic and texts/cultural resources

Jesson et al. (2013) argue that writing is a dialogic process in which students' intertextual histories are key resources, as are their multiple cultural repertoires. These repertoires include home literacy practices - the kinds of texts that students read and produce in their home and community environments - as well as students' linguistic repertoires. In the context of the forum, intertextual resources include prescribed texts by scholars, the reading responses posted by other students, the online discussions with peers and lecturers together with their cultural, linguistic and professional repertoires. In the data analysis section, we illustrate how students negotiate roles and positions for themselves through appropriation and use of the textual resources available to them on the forum (Jesson, Parr, and McNaughton 2013, 220).

A critical dialogic approach and epistemic access

Our conceptualisation of epistemic access is not limited to providing entry level postgraduate students with access to disciplinary knowledge, discourses and values. While this is an important part of our work, it is not enough. We are interested in being/knowing and how these intersect on the course and ultimately contribute to students reconfiguring knowledges. Our conceptualisation of epistemic access resonates with the work of Luckett (2019) who argues for the importance of broadening "the concept of 'epistemological access' to include socio-cultural and ontological access and taking into account the effects of our own positionality and institutional roles" (Luckett 2019, 55). We are interested in giving students access to multiple knowledges and opportunities for reconfiguring knowledge. This critical dialogic approach opens up possibilities for broadened understanding in a number of ways: Students have dialogues with texts, with self and others (peers and lecturers). In addition, in responding to texts and peers on the forum they draw on their identities, their socio-cultural contexts, and affect. Through this process of multiple dialogues students gain access to disciplinary knowledge and reconfigured knowledges.

THE CURRICULUM AND ITS ENACTMENT IN SHIFTING CONTEXTS, 2019-2021

While the core curriculum of LLTP remained relatively stable from 2019 to 2021 and addressed similar themes, in 2020 a substantial shift in pedagogy resulted from the sudden move to teaching and learning in online mode. The main aims of the course over the three years were to introduce key theoretical debates in the field of literacies and languages, to develop students' ability to move between teaching practice and cutting-edge theory, and to encourage students to examine these concepts in South African contexts and in relation to their own classroom practices.

In 2019, the 14-week long course was facilitated wholly in person. Students were required to read two or three academic articles per week in preparation for a weekly two-hour contact session. This session typically consisted of a short lecture input, often based on a PowerPoint presentation. Video extracts were sometimes used as a stimulus for classroom activities. Students were required to read the prescribed texts in advance to facilitate classroom discussions and at times made presentations on course readings. Unfortunately, both discussions and presentations were rarely quite as dialogic as anticipated and were often restricted to the lecturer and the handful of students who had completed the reading or who felt confident to speak. Some students, although prepared, seemed uncomfortable with expressing their views in a classroom setting.

With the advent of Covid-19 in 2020, the course was suddenly shifted online and the lecture part of the contact class was replaced by an asynchronous narrated PowerPoint presentation. Through a chunking process, videos that had previously been part of a lecture were added as separate activities with questions to students (questions which otherwise would have been posed during a face-to-face discussion), and further videos were added. Our greatest concern was how to replace the class discussions which we considered integral to the course even when these were not entirely successful. To encourage at least some dialogue and engagement, we settled on weekly reflexive reading response tasks (see Appendix 1), in an asynchronous forum discussion, as the dialogic engine of the course. In 2020, having assumed that this would be a "second best" way of engaging, we were surprised by the initial high level of engagement although this did taper off towards the end of the course in terms of quality and quantity, specifically in terms of students' responses to each other in the discussion forums.

In 2021, to encourage a sustained level of dialogic engagement, we took three additional measures to elicit maximum participation in this strange (to us, at least) online space. Firstly, we changed the settings for the response forums so that students could only see each other's responses once they had posted their own. Secondly, we adjusted the assessment framework to include the participation bonus into the mark structure of the second assignment. Thirdly, we replaced a few long and very challenging texts with more accessible texts and consciously selected a range of genres, including scholarly articles, reports and newspaper articles (see Appendices 2 and 3). We were astounded by the level of investment and effort week after week by the entire 2021 cohort. In the remainder of this article, we investigate the journeys of two students from this cohort with the aim of indicating the affordances of this online mode of student engagement and to show why, post Covid-19 restrictions, we will move towards a blended-learning approach.

METHODOLOGY

Having decided to research students' responses to the online versions of LLTP, for this case study we needed to select texts written by specific students and to identify and analyse the multiple discourses evident in both students' weekly and summative reflexive reading response assignments. This was a long and messy process. Eventually, for the purpose of producing an article of acceptable length, we decided to focus on the early weekly reflexive reading response tasks (submitted as online forum posts) of the 2021 cohort, together with their summative reflexive reading response assignment. In order to contextualise the responses analysed in detail for Week 3, we reviewed the responses from Weeks 1 and 2. We chose to focus on Week 3 because by this time students could be expected to understand more fully what was required of them than had been the case for some of them at first. Written permission to use students' writing was obtained from all students in the 2021 cohort.

To further focus our analysis and discussion, we examined the learning journeys of two students who were neither the weakest nor the strongest in terms of their assessed performance on the course. These two began with differing levels of conceptual understanding of the theories and practices explored during the course and differing abilities to respond in writing to the tasks. The first student (Refilwe)1, a practising teacher, engaged quite strongly and productively from Week 1 onwards. The second student (James), a recently graduated student with only teaching practicum experience, was initially considered "at risk" of failing, but persevered and passed.

In analysing responses to the forum tasks and to the assignment, evidence of dialogism, was key in coding data. We examined students' interactions with texts, with themselves (reflexivity), and with each other and their lecturers (multivoicedness). We coded the data from the forum responses of the two students selected as well as from their interactions with others and moderated each other's interpretations of this data.

The weekly reflexive reading response task (see Appendix 1) enabled analysis of the dialogic process as it relates to reflexivity. In this task writers shared their thoughts on and responses to their academic journey as they engaged with the various course activities. In their writing there is evidence of how students began to re-think, re-imagine, and critically interrogate their ideas and apply these to their lives, their teaching contexts, and wider South African contexts.

In identifying evidence of emerging dialogism in students' weekly tasks and summative reflexive reading response assignment, we drew on some of the tools for discourse analysis developed in systemic functional linguistics. In particular, we used the work of Martin and Rose (2003) on the appraisal strand of discourse analysis because appraisal "is concerned with evaluation: the kinds of attitudes that are negotiated in a text, the strength of the feelings involved and the ways in which values are sourced and readers aligned" (Martin and Rose 2003, 22). In the extracts from student writing which we quote in this article, words and phrases central to our analysis are presented in italics.

Having set the scene, we now present and analyse selections from the weekly tasks and summative reflexive reading response assignments of two students from the 2021 cohort.

EARLY WEEKLY REFLEXIVE READING RESPONSES

In the LLTP course (see Appendix 3), Week 1 introduces students to key concepts in rethinking literacy and language, while Week 2 considers the turn towards seeing language and literacies as social practices. The content challenges narrow views of literacy and language and makes important links to language, power and identity. Students are expected to engage asynchronously with visual images about literacy and with a narrated PowerPoint in which the lecturers introduce key concepts. These ideas are developed through two key readings (Wa Thiong'o 1992; Janks 2009).

James: Taking the bull by the horns

James starts his journey as one of the weaker students on the course. His very brief response indicates that he has not engaged sufficiently with the requirements of the task and his forum post is formulaic in structure (Zygouris-Coe, Wiggins, and Smith 2004). He summarises key points from the Ngugi Wa Thiong'o (1992) reading, points out what he finds interesting, and ends with questions to the author. This strategy serves James well in helping him to achieve a level of criticality that he loses as he departs from it in subsequent weeks. In this first week, he takes a stance against the Wa Thiong'o (1992) text, and concludes by asking two questions that help him frame his own thinking on the topic.

'The part that I do not agree in Ngugi's writing is that written and spoken languages are similar. In my opinion they are not. This is because writing is rule governed. What do I mean by that? I means that (...) The question I would ask Ngugi would be, what steps can be taken to promote African languages? In addition, I would ask him, is it possible for all African countries to select a single African language and promote it as a unifying language?"

Although James's response indicates that he misunderstands Wa Thiong'o's (1992) intention, his questions, in an imagined dialogue with Wa Thiong'o, are a valuable part of the learning process and his placement of "The part that I do not agree" and "The question I would ask Ngugi" in theme position (Martin and Rose 2003) in his sentences foregrounds a confident personal voice.

In the second week, James expresses his frustration with the demands of postgraduate reading:

"I must admit, I don't like reading long texts because it is challenging for me to concentrate and get the gist of what I am reading about."

And also reflects on his learning process:

"I managed to learn more about discourse and was able to determine at least three communities and discourses I use within these communities."

"I was able to determine what my identities are and what I do when I am on those identities."

In this post James shows meta-cognitive awareness and some ability to reflect on his learning journey and its challenges.

Refilwe: Beginning to see through new lenses

From the outset, Refilwe uses reflexive language to engage with the course. In her first response to another student (Andrea), who argues for the need to move beyond reductionist views of literacy, Refilwe agrees with Andrea, elaborating on shifts in her thinking that are emerging from her dialogue with both Wa Thiong'o (1992) and Janks (2009) as well as with other students. She amplifies the force of her realisation by including the intensifying adverb (Martin and Rose 2003) "finally":

"Having read the definitions of literacy from the two articles, I finally realise that we are not doing literacy justice if we reduce it to either/or."

In her first weekly reading response reflexivity and engagement with key concepts and debates in relation to the readings, are strongly evident. However, most striking are her formulation of questions and her application of key concepts to her personal history. Through the lens of Wa Thiong'o's (1992) Decolonising the Mind she revisits her view of African languages:

"This argument makes me realise how African languages have been belittled and perceived as 'backward' in the sense that Africans have to struggle to express their ideas, ideologies and interests in a foreign language as if it is the measure of intelligence."

Her engagement with Ngugi also enables her to reflect on her missionary school education where "We were compelled to unlearn all of our African values and to see the world through the eyes of the missionaries. Looking back, I realise this language was used to disassociate us from our own culture and to accept the missionaries' culture as the superior and normal one." Here, her personal voice blends with an emerging scholarly voice. Throughout this first weekly reflexive reading response task Refilwe moves with agility between different voices. She ends with a question that foregrounds her teacher voice and identity in which she problematises the dominance of English as LoLT and raises questions about how to end this dominance. In our response to her, we refer her to some decolonial scholars who argue for expanding what counts as knowledge rather than replacing one form of knowledge with another. Hence Week 1 ends with a further challenge to her thinking which she takes up in her later responses.

WEEK 3 REFLEXIVE READING RESPONSE TASKS

Week 3 focuses on the impact of the social turn on reading and writing pedagogies, practices and research. These ideas are developed in three key readings from the work of Cliff-Hodges (2010), Nixon, Norman, and Robledo (2021) and Woodard, Vaughan, and Machado (2017) on culturally responsive approaches to writing pedagogy. The reading of these texts is complemented by engagement in the asynchronous session tasks on rethinking reading from personal and professional perspectives, a video on critical literacy (Luke 2013) and a narrated PowerPoint in which the lecturers introduce key concepts.

James: Retreating from dangerous waters

Though James has gained an increased understanding of the requirements of the weekly reflexive reading response tasks, he still relies heavily on the personal voice, as indicated by phrases such as "I loved his ideas" and "Cliff-Hodges' article (...) was educational". His scholarly voice is limited to statements such as "I agree with these arguments". When he speaks with the voice of a teacher, it is again to show how his teaching strategies align with those evident in the weekly readings.

James no longer indicates where he disagrees with texts, possibly because he lost the confidence to do so after some of the misunderstandings evident in his first two responses were pointed out to him. He confines his writing to what he likes about texts, or to showing alignment with the views of the authors.

"I have found these week's content very intriguing. I agree with Pearson and Stephens' (1994) view that reading is acknowledged as linguistic, cognitive, social and political. (... ) I loved [Luke's] ideas about teaching methods."

In James' writing there is still limited evidence that he understands core arguments and key concepts in most of the texts, and at times evidence of misunderstanding. For example, in responding to an article on youth-led and youth-centred writing practices which aim to empower under-represented students, honour various perspectives and provide students with agency as part of a culturally sustaining pedagogy (Nixon et al. 2021), James uses as an example a class designed around an advertisement for acne-clearing face wash. In justifying his choice of advertisement as an example of learner-centred pedagogy James clearly misconstrues the intention of culturally sustaining pedagogy discussed in the reading to which he is responding. He makes generic links to students' lives, rather than assisting them to become more critically and culturally conscious. At this stage, James fails to make any connection between the arguments in the various texts, or to concepts introduced in the first two weeks of the course. The dialogue remains limited to engagement with isolated ideas of single authors and his own immediate reactions to these ideas.

Refilwe: Recursive moves across texts and voices

The reflexivity and engagement with key concepts and debates in relation to the readings demonstrated in Refilwe's first weekly reflexive reading response task, are strongly evident in Week 3. However, what is most striking is her formulations of questions, and her dialogic engagement with texts, peers and lecturers in her quest to find answers. Throughout her response Refilwe moves between different voices, her personal voice, her teacher/professional voice and her emerging scholarly voice, at times integrating all of these by effectively applying theory to her personal and professional experiences. Refilwe begins with an explicit image of an intellectual journey in which she moves between past and present and reflects on changes to her understanding:

"As I navigate back to Ngugi and his ideas of decolonizing the mind, Kucer and Gee's arguments about literacy and discourses and now Woodard and Nixon's attempts to employ writing pedagogies that are culturally friendly, I begin to understand the significance of identity and context in literacy."

In this opening, Refilwe works explicitly on pulling together her learning from the first three weeks of the course, connecting the texts she has read to each other and the broader concept of identity and context in relation to literacy and language. She is aware that this is a beginning ("I begin to understand") and that she still has some distance to travel. She is gathering intellectual artefacts along the way and steadily building a dialogic conceptual framework.

In contrast to James, Refilwe dives into a discussion of culturally responsive pedagogies, immediately foregrounding the key concepts and the main finding from Woodard et al. (2017). As she is still making sense of these new ideas, the first part of her response is mostly a summary of them.

"In Woodard's attempts to investigate the means of employing cultural (sic) pedagogies that encourage cultural and linguistic pluralism, a research was conducted, and it revealed that the teachers who were successful in integrating culture into writing usually incorporated clear discussions of language, culture and power in the writing techniques. (...) Nixon brings up the youth centred writing approach which he believes will resolve the problem."

She deals with Woodard et al. (2017) and Nixon et al. (2021) in interesting ways, using Woodard et al. (2017) to set up the problem (the need to centre students' identities and linguistic and social resources) and Nixon et al.'s (2021) youth centred approach to writing for more practical and specific ideas for solving the problem. In doing so she makes more direct connections between the texts than James is able to do. However, her understanding of culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP) is preliminary (not yet a deep, substantial understanding) and this becomes evident in some of her discussion about applying CRP to South African curricula and classrooms.

Having grappled with key concepts in a novice academic voice, Refilwe shifts gears into her more confident teacher voice and professional identity. She poses the question: "Does our South African curriculum accommodate such a pedagogy that is culturally inclined?" and answers it by providing some ideas for how such accommodation could be achieved. Her use of the modal "can" (i.e., it is possible to do this) and her choice of the noun "urgency" add to the persuasive force of her writing:

"The writing curriculum can be modified in a way that topic choices (especially in Paper 3 in the South African context), audience, grammar and assessments given, display the urgency of cultural integration."

Still using her teacher voice, Refilwe raises important and interesting questions about teacher agency and the extent to which such agency is constrained by institutional power structures. In responding to a discussion in the Woodard et al. (2017) article about teachers who "got into trouble" (Refilwe's words) for allowing students to draw on a range of languages and varieties in their classes, Refilwe extends this discussion by drawing on Althusser's (1971) conceptualisation of the tensions between structure and agency. This discussion resonates strongly with other students in the discussion forum as will be illustrated later in the article.

Refilwe ends her reading response with an important question which, in keeping with the dialogic nature of the discussion forum, is framed collaboratively:

"Our question has been - should we then stop teaching grammar in class, and if we should continue, where in the curriculum should we accommodate it since Chomsky's drill has been criticised. Haddix (2018) responds by indicating that there are multiple ways of writing, multiple purposes of writing, as well as multiple genres. In a nutshell, in the process of students writing about their personal experience, they grasp the grammatical rules and structures."

This extract represents an important moment in Refilwe's journey as she asks the "where to next" question. Implicit in this question is whether to throw the baby out with the bathwater or whether there is a middle ground. Refilwe's initial responses (and those of many other students) demonstrate that she does not yet have the breadth of knowledge to find the nuance of the middle ground - in this instance, the middle ground of contextualised, meaningful grammar and writing pedagogy. However, such a nuanced, middle ground position emerges over time through the dialogic process so that in her summative reflexive reading response assignment, Refilwe is able to draw together ideas gained from peer and lecturer feedback and dialogue, as well as knowledge accumulated from the course as a whole.

FINAL REFLECTIONS: REFILWE'S AND JAMES' SUMMATIVE REFLEXIVE READING RESPONSE ASSIGNMENTS

In the summative reflexive reading response assignment, each student charts their own journey through the course guided by the intellectual, personal and emotional maps that they bring, in ways that resonate with Bruner's (2020) seminal work on the itinerary of readers and writers:

"As our readers read, as they begin to construct a virtual text of their own, it is as if they were embarking on a journey without maps - and yet, they possess a stock of maps that might give hints, and besides, they know a lot about journeys and about mapmaking. First impressions of the new terrain are, of course, based on older journeys already taken. In time, the new journey becomes a thing in itself, however much of its initial shape was borrowed from the past." (Bruner 2020, 35-36).

Although Bruner's focus is on the creation of fictional and literary texts, the essence of his argument is congruent with Refilwe's and James' contrasting journeys through the course.

James

James shows remarkable mindfulness of his personal growth process. He acknowledges that he started the course with a very limited understanding of what was required and shows a metacognitive awareness of the trajectory of his growth. His references to the dialogic connections between himself, texts, fellow students and course lecturers (cf. Freire 2005) provide evidence of the "multiple dynamic interactions" necessary for effective dialogism that are referred to by Mendelowitz et al. (forthcoming). To illustrate his personal growth process, we include a long extract from his assignment:

"Language and Literacy Theories and Practices module has played a crucial role in assisting me comprehend literacy in an in-depth manner. (...). Every week, we (students) wrote reflexive reading responses for topics we covered those weeks, individually. Thereafter, we commented on one another's readings. It was a tremendous experience having to read fellow students ' responses and comments. (...) [In Week 1], other students have done extremely well in their responses. I felt the pressure because my reading response for week 1 was tame and I needed to improve and redeem myself. (...) Throughout my [previous] learning journey as a scholar, I have not read critically. I would read for the sake of comprehending what the reading is about, and I would not thoroughly anoint [sic - annotate] a text and trying to understand and critique the author's viewpoints. This course has changed my approach to reading. I am now able to engage with the reading (...)."

"I believe it shows awareness that as a postgraduate student, I should not only rely on the course material offered by the lecturers. I should consult other texts and link them with the ones that are already available, especially if they cover the same topic. (...). However, I failed to thoroughly engage the reading with my reflexive reading response. I did not make use of theories in the readings to support my claims and arguments. That was one of my lows in my journey throughout this course (...). From the mistakes I have done and feedback I received from the lecturer, I attempted to (... ) show that I have interacted with the text and the points I am making are in line with the theoretical aspects of the texts I give an account for."

The weekly reflexive reading response tasks posted by his peers gave James a benchmark against which he could evaluate his own writing in a relatively non-threatening way. This was an affordance that had not been available in the face-to-face iterations of this course. The affective force (Martin and Rose 2003) of the language in expressions such as "tremendous experience", "felt the pressure", "tame" and "redeem myself" informs readers of the strength of James's feelings about the course, himself and his learning journey. James's narrating self as both subject and object in the online forum enables him to see himself as other, through his own eyes and the eyes of others (Bradbury 2019).

The dialogic nature of the forum helps James to model his academic discourse and engagement on that of fellow students' reflexive responses, thus leading to a changed "approach to reading" and a growing "awareness" of the requirements of postgraduate studies. He learns to negotiate new roles and positions for himself and to build bridges between the resources he accumulated during his undergraduate studies and the voices, knowledge and cultural capital other students bring with them (Jesson et al. 2013; Bourdieu and Passeron 1994). By being a dialogic reader of a variety of academic and student texts, he learns to be a better producer of these texts. It is not an easy journey, because by the seventh week of the course, he still experiences "one of the lows in [his] j ourney throughout this course" when he receives feedback that his engagement with readings is still not critical enough.

However, constructive feedback helps him to persevere, and to move from a narrow conceptualisation of language and literacy towards the somewhat more complex understanding expressed in the conclusion to his assignment. James now views languages and literacies as communication tools which enable him to "address colonisation and decolonisation", and to "re-design old practices that have been put in place to promote equity in the educational context and the society at large". Ball and Freedman's (2004, 6) words could not be more true than they are for James: "The role of the other is critical to our development; in essence the more choice we have of words to assimilate, the more opportunity we have to learn".

James's early responses to readings had suggested that he would be unlikely to achieve the course outcomes. Although his later responses do not show the same evidence of scholarly development as those of stronger students, his continued dialogic engagement with audience and texts, and his continued efforts to model the responses of other students, resulted in sufficient growth for him to pass. The course, and the learning opportunities provided by the forum offered James the scaffolding he needed to reach the minimum course outcomes though not, perhaps, to be adequately prepared for higher levels of postgraduate study.

Refilwe

Refilwe begins her summative reflexive reading response assignment with a metaphor that highlights how the course has transformed her thinking in profound ways.

"I feel as if I have undertaken a six-month journey whose origin is in the desert with no human interaction and the destination is India, a country with 23 official languages. I say this because I can now distinguish between my former and my current self. ... I am glad to say, this fulfilling journey I took with Ngugi Wa Thiongo, Lecturer x and other scholars has shifted my paradigm. ... I am no longer in a desert. I have climbed the multilingual and critical literacy stairs towards my re-identification. I am proud to say, I can now refer to myself as a linguist."

Refilwe's opening lines (and indeed the rest of the assignment) demonstrate that learning is a deeply personal, emotional and creative process and that, as ideas shift, the self is reshaped. Her metaphor of the shift from intellectual isolation in a desert bereft of nourishment towards the richly multicultural and multilingual space that is India, signals two aspects of her learning journey: the move from learning and thinking alone towards dialogic learning and thinking, and her realisation that multilingualism is a resource that must be valued (for herself and her learners). Throughout the assignment, she reflects on her intellectual, identity and pedagogic shifts. She approaches the reflexive reading responses (both formative and summative) with personal self-confidence and frankness, expressing confusion, posing difficult questions as the need arises and making clear to readers her positive response to the course and to what she has learned (e.g., "glad" and "proud").

Refilwe positions her shifting self (personal, teacher, scholar) at the centre of the assignment. She juxtaposes her past and present self in relation to her mission school memory, how it shaped her personal and professional teacher identities, and how her current self reinterprets these through new theoretical lenses:

"Perhaps my most vivid reflection is my missionary school, where one had to be English to be right (...). I had to fight hard to be anglophile in order to fit in. It got worse when I became an English teacher who emphasised the rules of English rather than meaning. I fancied myself an English pundit, hence I stressed this anglonormative ideology to my learners."

She relates this discussion about her shifting self to the identity theory she encountered through her engagements with Peirce Norton (1995) and Hall (1992). She realises that identity is multiple, shifting and contradictory and this realisation empowers her to do further self-reflexive identity work. An important moment for Refilwe is her engagement with the America Ferrera (2019) TED talk titled: My identity is my superpower:

"It made me realise that I was not the only one facing the predicament of marginalisation. Instead of feeling embarrassed like I was at the missionary school, and forcing myself to shift my identity to satisfy the system, I realised it was the system that I had to force to accept me."

This significant realisation enables Refilwe to make connections between two different aspects of her language history and identity - that learning English at mission schools and IsiZulu as an immigrant to South Africa from Zimbabwe, were both driven by social and economic pressures, the desire to belong in different spaces. In this discussion, Refilwe slips between Peirce Norton's (1995) socio-cultural conceptualisation of investment and the psychological notion of motivation. But despite this slippage, the point she makes is an important one, as it comes with the realisation that there is more scope for change and agentive challenges to the status quo than she had thought possible.

As Refilwe finds the beginnings of answers to her questions, she articulates a growing sense of agency in relation to her classroom pedagogy. In her first weekly reflexive reading response task, she raised questions about multilingualism in relation to Wa Thiong'o (1992). But finding answers to these questions was a recursive process. At one point she felt on the verge of paralysis:

"For a moment the topic on multilingualism seemed too complicated for me. I kept asking questions as to how practical it is for a multilingual country like South Africa to implement mother tongue education. I kept thinking that we are biting (off) more than we can chew." (Week 10)

However, the combination of her dialogues with multilingualism scholars (Sibanda 2019), CRP scholars (Nixon et al. 2021), critical literacy scholars (Janks 2009; Govender 2019) and lecturers enable her to find a way forward. Most significant is her realisation that she can be a change-agent in her classroom, expressed in the contrasting affective language used to describe her past and up-to-the-present teacher positions ("passively waiting") and her future position ("I am ... responsible for this change"). Ongoing dialogues with lecturers helped her to differentiate between change at micro (in her own classroom) and macro policy levels. Her dialogue with the abovementioned scholars equipped her with a theoretical framework and pedagogical strategies for immediate classroom implementation. She concludes that:

"I have been passively waiting for the system to change so that multilingual education is effected, little did I know that as a teacher, I am amongst the stakeholders who are responsible for this change. ... Teachers need to come up with creative pedagogical activities that incorporate multilingualism in the classroom context before we can expect the policies to transform."

Refilwe finds answers to her questions - but these are not neat, fixed answers. It is the beginning of dialogues that will continue throughout her honours programme and beyond as new questions arise. While James's assignment foregrounds what he learned from other students in the discussion forum, Refilwe does not mention the role of peers in her learning process. This does not mean that peers did not play a significant role in her learning (as we illustrate in the forum discussion section), but rather that she chose to focus on her ongoing dialogue with texts, self and her lecturers which was central to her intellectual quest. Ironically, her summative reflexive reading response assignment does not illustrate the substantial shift in reflexivity evident in James' assignment. We suggest that their different foci relate to their different departure points at the beginning of the course. While James finds academic discourse challenging and unfamiliar, as he confessed in his Week 2 response, Refilwe began with a solid understanding of academic discourses and places her questions and concerns at the centre of her journey.

ANALYSIS OF WEEK 3 FORUM DISCUSSION DATA

The experience of coding and analysing the forum discussion data was somewhat like landing in the middle of a live class and trying to make sense of it in the moment. Unlike discrete texts such as individual reading response posts, the data in the forum discussion does not stand still. The collaboratively written online text is that strange genre of written down spoken language that is quite typical of online forums.

Was there a specific affordance of the discussion group and if so how did it extend the dialogic process discussed in the previous section? We argue that the discussion forum takes the dialogic play of voices to another level, with the dialogues between students, texts and lecturers happening alongside the multiple voices of students in the weekly reflexive reading responses. Students start getting a sense of how their ideas have journeyed across spaces and the extent to which they have reached their audience of fellow students and lecturers (Thesen 2014).

In Week 3, students debated the implications of reading and writing as social practices and the implications for balancing creativity and self-expression with the need to master standard English, the scope for identity work and cultural responsiveness. In the extract that follows, two students respond to Refilwe's Week 3 reflexive reading response in the context of the broader discussions highlighted above.

Andrea: "I was shocked by the teachers that were reported for allowing students to draw on their first language for help in English grammar for example. I agree with the argument in structure and agency as well, it seems as teachers, we are encouraged to exact change and assist in creating a sense of voice and acknowledgement of identity but we are not always supported by the demands of the curriculum and the department. I feel there is a discrepancy in the requirements, I also express this view in my own response to this week's readings. Furthermore, I agree with your final point about Grammar instruction-I am also not certain about teaching grammar in the classroom or finding other ways to communicate language use in the classroom, which links to my previous comment where I questioned what the standard use of a 'standard language' and how this would play our in practice."

James: "I love your synthesis about youth centered writing. I agree that some groups of learners are marginalized when it comes to their language. It is good integrating other varieties of a particular language in a speech utterance. This helps in promoting the language and shows inclusivity among all speakers of that particular language. I believe that translanguaging as a teaching method is effective .... Moreover, I fully agree with your views that from a South African point of view it is vital for teachers to familiarize themselves with multiple and diverse cultures we have in the country in order to understand the leaners' needs and expectations for their cultural point of view. This will help in facilitating the teaching and learning process effectively."

This extract highlights patterns that are common to the majority of students' posts to each other across the fourteen weeks: affirmation, a high level of affect, building on each other's contributions, occasional questions to each other, misunderstandings of each other's responses and limited criticality. One of the most striking aspects of the week three discussions is the strong presence of different kinds of teacher voices: expert teacher voice, confused teacher voice (So what? What do we do now?), personal/professional voice, critical teacher voice.

Andrea begins her response with a high level of affect, expressing her shock that teachers in the Woodard et al. (2017) study were censured for creating classroom space for learners' first languages. She also expresses agreement with Refilwe's argument about the tension between structure and agency as well as the challenges of teaching grammar in meaningful ways and elaborates on each of these points from her perspective. She builds critically on Refilwe's teacher agency argument by foregrounding the contradictions between the requirements that teachers promote diversity and identity spaces in the classroom and the frequent undercutting of these requirements by the rigid curriculum and bureaucratic demands of the department of education. She ends by joining Refilwe in assuming an uncertain/ confused teacher voice in relation to grammar teaching and questions the notion of "standard language". In summary, Andrea's response moves between affect, agreement, critical teacher voice and confused/ uncertain teacher voice.

James begins his response to Refilwe with affirmation, a high level of affect and agreement: "I love your synthesis" "I agree that some groups of learners are marginalised when it comes to their language"). His agreement is significant in suggesting that he now has some understanding of what he had misunderstood in his own reflexive reading response. Given that students could not see other's responses before posting their own, it is likely that the forum dialogue helped James to understand the content of Week 3.

Throughout the forums, James responds most confidently and passionately to discussions about linguistic diversity, writing in a blend of his teacher and personal voice about experiences of being linguistically marginalised as a learner and his response to these experiences. Although he has experience of teaching only from the teaching practicums during his undergraduate degree, he draws on these experiences to assert an expert teacher voice in responding to Refilwe. In this voice he makes value judgements ("It is good integrating other varieties, I believe that translanguaging (...) is effective", "it is vital for teachers to") and suggests that the strategies he advocates will help facilitate more effective teaching and learning processes, even though he has limited conceptual and practical understanding of these strategies.

We frequently found that the forum discussions, while rich and interesting, ended somewhat abruptly with no further response from the recipient of the feedback - as would be usual in this kind of conversation face-to-face. For example, there is no response from Refilwe to the feedback from Andrea and James. This does not mean that the feedback was not taken up, but it was not explicitly engaged with here. The lack of further response might relate to a limitation of the online platform - that there are no notifications sent to forum users when there are new messages - or it or may indicate that once students have met the criterion of responding to 2-3 students on x number of forums to obtain their bonus mark, they move on to other commitments in their studying and work lives.

As we coded and analysed the discussion forum data, we were struck by how productive this forum became for students and how much we as lecturers learned from our engagement in the discussions.

CONCLUSION

Having focused on three separate but interlinked strands of the students' participation in the course through their online writing, in this concluding section we reflect holistically on the affordances and limitations of this online version of LLTP for student and lecturer learning. Empirically, this article has offered a detailed account of dialogic processes across different tasks and assignments which we hope will contribute to the theorisation of dialogic teaching and learning in online postgraduate contexts. Of particular relevance is the intersection of different kinds of dialogic processes and how they work together to enrich student learning.

To our surprise, analysis of students' weekly and summative reflexive reading responses suggests that the affordances of the move online have been greater than the limitations, for both academically strong and struggling students. One likely reason for this is the permanence and visibility of the forum responses. They are available for students to revisit in order to revise or extend their understandings of course content and also of how to express their responses to this content in academically "standard" and risk-taking ways (playing with ideas and ways of expressing them in a range of voices). Furthermore, students are afforded more time to construct their thoughts in written mode while modelling the strengths they observe in peers' responses to previous weeks' readings. The affordances of the written mode of interaction contrast with the ephemerality of in-the-moment classroom discussion in which more confident students are likely to engage while others keep silent. One result of the inclusion of the discussion forum was improvement, both quantitatively and qualitatively, in students' engagement with and understanding of the texts they read, together with more confident writing in a range of voices.

One limitation of the online move has been the lack of sustained discussion threads from week to week - threads quite easily enabled when lecturers and students are meeting face to face. For post-pandemic blended learning iterations of the course we need greater understanding of the affordances of digital technology for making such threaded discussions possible.

In both 2020 and 2021 there was uneven development of criticality in students' forum posts. In their responses to one another this may be a consequence of only meeting virtually and of not being able to read body language clues as would be the case in a classroom, or of limited understanding of the discourse of criticality (Gee 2007; Reed 2005).

We give James and Refilwe the final say: "It [the LLTP course] was a tremendous experience having to read fellow students' responses and comments" (James, summative assignment) and "Through this module, I have managed to frame a research topic on multilingual education. I am very optimistic that with my lecturers, Ngugi wa Thiongo, Janks and other scholars on my side, my research will yield fruit" (Refilwe, summative assignment). To continue with Refilwe's metaphor, the pedagogic decision to introduce compulsory forum posts, available for all to view and to use in ongoing dialogues with established scholarly voices, with fellow students and with themselves, has already borne fruit. In forthcoming iterations of the course, we plan to continue the weekly reflexive reading response task in the context of blended learning. By doing so we hope to retain the benefits of the online forum alongside the affordances of selective face-to-face meetings for enabling both epistemic access and academic success.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported in part by the Teaching Development and Research Grant from the University of the Witwatersrand, under the project entitled "Humanising the curriculum: Creating critically dialogic communities of leaners online".

NOTE

1 Pseudonyms are used for all students referred to in this article.

REFERENCES

Althusser, Louis. 1971. "Ideology and ideological state apparatuses." In Lenin and philosophy and other essays, ed. Louis Althusser, 79-87. New York: Monthly Review Press. [ Links ]

Badenhorst, Cecile and Cally Guerin. 2015. Research Literacies and Writing Pedagogies for Masters and Doctoral Writers. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaïlovich. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaïlovich. 1986. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Translated by Vern McGee. Edited by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1994. "Introduction: Language and the Relationship to Language in the Teaching Situation." In Academic Discourse: Linguistic Misunderstanding and Professorial Power, eds. Pierre Bourdieu, Jean-Claude Passeron, and Monique de Saint Martin, 1 -34. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Bradbury, Jill. 2019. Narrative Psychology and Vygotsky in Dialogue: Changing Subjects. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bruner, Jerome. 2020. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Cliff-Hodges, Gabrielle. 2010. "Rivers of reading: Using critical incident collages to learn about adolescent readers and their readership." English in Education 44(3): 181-200. [ Links ]

Feldman, Jennifer. 2020. "An ethics of care: PGCE students' experiences of online learning during Covid-19." Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning (CriSTaL) 8(2): 1-17. [ Links ]

Ferrera, America. 2019. "My identity is a superpower - not an obstacle." Video, 14:02. https://www.ted.com/talks/america_ferrera_my_identity_is_a_superpower_not_an_obstacle/transcript?language=en. [ Links ]

Freedman, Sarah Warshauer, and Arnetha F. Ball. 2004. "Ideological becoming: Bakhtinian concepts to guide the study of language, literacy, and learning." Bakhtinian Perspectives on Language, Literacy, and Learning, eds. Arnetha F. Ball and Sarah Warshauer Freedman, 3-33. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Freire, Paolo. 2005. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. (20th Anniversary edition). New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Gee, James. 2007. Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Govender, Navan. 2019. "Can you see a social issue? (Re)Looking at everyday texts." https://pureportal.strath.ac.uk/en/publications/can-you-see-a-social-issue-relooking-at-everyday-texts. (Accessed 15 September 2019). [ Links ]

Hall, Budd L. 1992. "From margins to center? The development and purpose of participatory research." The American Sociologist 23(4): 15-28. [ Links ]

Janks, Hilary. 2009. Literacy and Power. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jesson, Rebecca, Judy Parr, and Stuart McNaughton. 2013. "The unfulfilled pedagogical promise of the dialogic in writing." International Handbook of Research on Children's Literacy, Learning and Culture, 215-227. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Kiley, Margaret. 2015. "'I didn't have a clue what they were talking about': PhD candidates and theory." Innovations in Education and Teaching International 52(1): 52-63. [ Links ]

Luke, Allan. 2013. "Second wave change." Video, 5:23. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RgciQLj-57k&t=3s. [ Links ]

Luckett, K. 2019. "A Critical Self-reflection on Theorising Educational Development as 'Epistemological Access' to 'Powerful Knowledge'." Alternation 26(2): 36-61. [ Links ]

Martin, James Robert, and David Rose. 2003. Working with Discourse: Meaning Beyond the Clause. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [ Links ]

Mendelowitz, Belinda, Ana Ferreira, and Kerryn Dixon. Forthcoming. Language Narratives and Shifting Multilingual Pedagogies: English Teaching from the South. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Nixon, Tiffani, Chris Norman, and Esmeralda Robledo. 2021. "Youth-led and youth-centered writing: A practice of healing." Literacies Across the Lifespan 1(4): 24-28. [ Links ]

Peirce Norton, Bonny. 1995. "Social identity, investment, and language learning." TESOL Quarterly 29(1): 9-31. [ Links ]

Reed, Yvonne. 2005. "Using students as informants in redesigning distance learning materials: possibilities and constraints." Open Learning 20(3): 265-275. [ Links ]

Rule, Peter, Eli Bitzer, and Liezel Frick. 2021. The Global Scholar: Implications for Postgraduate Studies and Supervision. Stellenbosch: African Sun Media. [ Links ]

Sibanda, Rockie. 2019. "Mother-tongue education in a multilingual township: Possibilities for recognising lok'shin lingua in South Africa." Reading & Writing-Journal of the Reading Association of South Africa 10(1): 1 -10. [ Links ]

Thesen, Lucia. 2014. "Risk as productive: Working with dilemmas in the writing of research." In Risk in Academic Writing: Postgraduate Students, their Teachers and the Making of Knowledge, ed. Lucia Thesen and Linda Cooper, 1 -24. Toronto: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Wa Thiong'o, Ngugi. 1992. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Nairobi: East African Publishers. [ Links ]

Woodard, Rebecca, Andrea Vaughan, and Emily Machado. 2017. "Exploring culturally sustaining writing pedagogy in urban classrooms." Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice 66(1): 215-231. [ Links ]

Zygouris-Coe, Vicky, Matthew B Wiggins, and Lourdes H Smith. 2004. "Engaging students with text: The 3-2-1 strategy." The Reading Teacher 58(4): 381-384. [ Links ]