Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.36 n.3 Stellenbosch Jul. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/36-3-4662

GENERAL ARTICLES

An examination into the role of a peer academic online mentoring programme during emergency remote teaching at a south african residential university

J. M. OntongI; S. Arendse-FourieII; C. SchonkenIII

ISchool of Accountancy Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5097-8988

IISchool of Accountancy Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7376-304X

IIISchool of Accountancy Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0447-2454

ABSTRACT

For residential universities, the COVID-19 pandemic in the 2020 academic year necessitated the suspension of in-person lectures and a swift transition of classes and other in-person activities to emergency remote teaching (ERT). This included the academic module mentoring programme, cognisant of the potential challenges experienced by first-year students during a period of ERT. The role of an in-person module mentoring programme before ERT was only to provide academic support to first-year students within an introductory financial accounting module to promote student success. This study investigated the role of an academic online mentoring programme for students in an introductory financial accounting module during ERT. A web-based survey was conducted to source the perceptions of both mentors and mentees who participated in an introductory module academic mentoring programme both before and during ERT to analyse whether the role of the academic module mentoring programme had shifted beyond that of academic support in an ERT environment. While academic support remained at the forefront as the main perceived benefit of the online mentoring programme, with the transition to ERT, the findings of this study illustrate an altering role that is more inclusive of additional psychological and peer support and engagement perceived benefits for first-year students who participated in an academic mentoring programme for students in an introductory financial accounting module during a period of ERT. Understanding student perceptions of the value derived for first-year students from an academic online mentoring programme is important in understanding first-year student needs and to provide relevant and applicable training to first-year students to promote student success during ERT. The findings of this study provide insight to institutions and in considering the addition of academic interventions such as offering academic online mentoring programmes during ERT and highlight the perceived value-add from both a mentor and mentee perspective.

Keywords: mentoring programme, emergency remote teaching (ERT), student support, module mentoring

INTRODUCTION

Student success and retention remain a challenge for South African universities (Ajoodha, Jadhav and Dukhan 2020). For students in their first year of academic studies, the challenge is even greater as they transition from high school to university (Broos et al. 2020). First-year students often approach higher education as regurgitators of information, which is a habit fostered as a successful approach to school studies (Ontong and Bruwer 2020). Du Preez, Steenkamp, and Baard (2013) list large student class groups with limited contact hours and access to lecturers, uncertainty as to what defines student success, lack of facilities, and language and diverse backgrounds as factors that hamper student success and student retention. Additional support measures beyond class contact time are often necessary to facilitate the successful transition during first-year studies, especially for students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Yorke and Thomas 2003).

Adams et al. (2010) found peer mentoring to be the most effective strategy to increase student retention and satisfaction. Due to the benefits associated with them and the cost-effective nature thereof, peer mentoring programmes have enjoyed increased support in recent years (Du Preez et al. 2013). Although the literature is ambiguous on the precise definition of mentoring, Crisp and Cruz (2009) describe the four domains of mentoring as psychological and emotional support, goal setting and career choice, academic subject-specific support, and role modelling. In particular, peer mentoring is when a more experienced student takes on a mentor role (Egege and Kutieleh 2015).

For the purposes of this study, the researchers investigated an online academic peer mentoring programme in an introductory financial accounting module during a period of emergency remote teaching (ERT) and learning. Due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak in December 2019, a global pandemic was declared in March 2020 (WHO 2020). Lockdown restrictions imposed and the restriction on the gathering of people in South Africa necessitated swift action for residential universities to go fully online by implementing ERT (Bozkurt and Sharma 2020). In the online academic mentoring programme, students who successfully completed the introductory financial accounting module are eligible to apply as mentors and are selected based on their marks achieved in the financial accounting module. The role of a mentor is to assist first-year student mentees with financial accounting academic work with the aim of increasing their academic performance in the module. The role of the online mentoring programme is academic support. Mentors are thus selected based on their academic performance in financial accounting and receive payment for their academic support services. Online meetings between mentors and mentees are held in small groups and are voluntary and informal. These online meetings do not form part of formal lecturing time and are held once a week during term time. Lecturers give no or very little direct input toward these sessions; the sessions are driven by the experience of the mentor, who has completed the module, and the questions asked by the mentees.

This study analysed the perceptions and reflections of mentors and mentees to understand whether mentees used the online mentoring programme to fulfil additional needs beyond those addressed by in-person mentoring programmes for an introductory accounting module. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the suspension of the traditional in-person mentoring programmes and therefore the transition to an online and ERT academic mentoring programme. This study therefore enquired whether the role of the online mentoring programme during ERT has changed from that of the traditional face-to-face peer mentoring programme that aims to fulfil mainly an academic subject-specific support role.

ERT is a temporary shift to an alternative educational delivery mode during a crisis (Hodges et al. 2020). Although future pandemics may result in ERT for only a limited period of time, other events, such as disruptive protests during the #FeesMustFall movement in 2015 and 2016 in South Africa (Sinwell 2019), may call on residential universities to engage in ERT in the future. This study identifies the nature of support and benefits, as well as the challenges, that universities and institutions may encounter in adopting an online mentoring programme in an ERT-type environment. The findings of this study may therefore prove useful to residential universities and institutions who offer academic support online mentoring programmes. The remainder of this article entails a review of relevant literature, followed by the methodology, data collection, findings, and conclusion.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review commences with a description of the transition to ERT. Thereafter the review describes the components and benefits of peer mentoring programmes as an effective strategy for student success. This is followed by a literature review of the ERT environment, which discusses the importance of online mentoring programmes during a time such as ERT.

In the first-year introductory financial accounting module, as described in this article, under usual circumstances, students have access to face-to-face lectures that they may attend, ask the lecturer questions after class, have in-person consultations with lecturers, and may attend voluntary small mentoring groups. During ERT, in-person lectures are replaced by compressed video recordings that cover the most important topics and students may ask questions via online platforms.

During ERT, in the introductory financial accounting module, students have less access to lecturers compared to face-to-face teaching solutions. For this reason, as well as personal home circumstances, it may be argued that asynchronous learning is preferred in the introductory financial accounting module during ERT to enable students to download and engage with course material when it is possible and convenient. Limited online synchronous activities are also provided during ERT to retain some student engagement.

Furthermore, it may be argued that students who already have trouble in the transitional first year of higher education under face-to-face circumstances may find further disengagement due to the online nature of ERT an additional hindrance to student success.

Peer mentoring

The literature notes a wide range of definitions of mentoring, such as Crisp and Cruz (2009) who note in excess of 50 definitions of mentoring. The four domains of mentoring provided by Crisp and Cruz (2009) are widely used in the literature in understanding mentoring; for example, in Collier (2017), Egege and Kutieleh (2015), Gunn, Lee, and Steed (2017), Lowery, Geesa, and McConnell (2018), and Lunsford et al. (2015). The four domains of mentoring include psychological and emotional support, goal setting and career choice, academic subject-specific support, and role modelling (Crisp and Cruz 2009).

York, Gibson and Rankin (2015) define student success by providing six key components; namely academic achievement, student satisfaction, skills and competencies acquisition, persistence, achievement of learning objectives, and career success. Egege and Kutieleh (2015) posit that the enablement of transitioning to higher education may contribute to student success. From the data collected from 17 institutions, the Hobson Retention Project established that peer mentoring is regarded as the most effective strategy to increase student retention and satisfaction (Adams et al. 2010). The engagement provided by peer mentoring is of particular importance to first-year students as they transition into higher education, as engagement contributes to a sense of belonging that assists in students seeking guidance when faced with difficulties (Egege and Kutieleh 2015). Furthermore, for 2021, the University of South Africa (UNISA) developed a student mentor training programme to equip prospective student mentors with graduate, personal, career, and learning skills to utilise in the mentoring of their peers (UNISA 2022), which highlights the key skills in peer mentoring.

Du Preez et al. (2013) investigated the perceptions of mentees and mentors of a peer module mentoring programme in Economic and Management Sciences (EMS), specifically with regard to the perceived contribution to student success. Du Preez et al. (2013) found the peer module mentoring programme to pose perceived benefits, both for mentees and mentors. The main benefits derived from the peer mentoring programme for mentees were related to academic performance, which corresponds to the mentees' main reason for enrolling in the peer module mentoring programme (Du Preez et al. 2013). Some students also listed additional perceived benefits and goals of the peer module mentoring programme beyond those of an academic nature, which included motivation and socialisation but the main aim was academic performance (Du Preez et al. 2013). As for the mentors, Du Preez et al. (2013) found the perceived benefits listed by the mentors to correspond with Jackling and McDowall (2008) and Beltman and Schaeben's (2012) work, who listed the main motivations as altruistic, cognitive, social, and personal growth. From Du Preez et al. (2013) findings, one can argue that peer mentoring programmes focus mainly on the academic subject-specific support domain of mentoring (Crisp and Cruz 2009).

The emergency remote teaching (ERT) environment and online academic mentoring

Hodges et al. (2020) define ERT as the temporary shift to an alternative educational delivery mode during a crisis, which differs from online learning which is designed to be online from the start. The main objective when implementing ERT is not to provide a robust educational solution but to implement a temporary alternative educational delivery mode in a quick and reliable manner in a crisis situation (Hodges et al. 2020). ERT differs from online learning as the latter is the planned robust delivery mode of teaching planned from the onset (Hodges et al. 2020). Although face-to-face teaching is often regarded as being superior to online learning, research suggest that this is not necessarily the case (Hodges et al. 2020). Hodges et al. (2020) argue that the hurried implementation of ERT during the COVID-19 pandemic to replace all traditional face-to-face offerings may further advance the perception that face-to-face learning is superior when compared to online learning if ERT is regarded to be the same as online learning. It is thus important to distinguish between online learning and ERT. Effective, high quality online learning results from a careful design process which will be absent in most instances in the rushed shift to ERT which entails swift conversion of face-to-face teaching offerings to an online offering as a temporary solution to an emergency situation (Hodges et al. 2020).

As described by Lembani et al. (2020), not all students have equal access to information and communication technologies. Furthermore, Bozkurt and Sharma (2020) describe ERT as "rushed into", where students are often overloaded with content while student engagement is an afterthought. Additionally, Bozkurt and Sharma (2020) express the importance of establishing supportive communities and that learning interventions should not only have the goal of purely learning subject knowledge but must be rooted in a pedagogy of care. An online mentoring programme was introduced as a possible solution to provide student engagement during ERT in an introductory accounting module.

The literature suggests that peer mentoring offers many benefits, such as enabling the transition to higher education (Egege and Kutieleh 2015), increasing student retention, success and satisfaction (Adams et al. 2010), as well as altruistic, cognitive, social, and personal growth and financial benefits (Du Preez et al. 2013). This study did not aim to answer the question of what is new in terms of ERT when compared to traditional face-to-face offerings and online learning. In the ERT environment, the research objective of this study was to explore whether the role of an online mentoring programme in an introductory financial accounting module has adapted and extended from its traditional role of academic student support, both from the perception of mentors and mentees, during ERT at a residential university.

METHODOLOGY AND DATA COLLECTION

Mentors and mentees were selected as participants due to their involvement in an online mentoring programme in an introductory financial accounting module, which took place during the second semester of the 2020 academic year during the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO 2020) and the sudden transition from face-to-face teaching to ERT. The selected online mentoring programme is based on an introductory financial accounting module in the EMS Faculty; the participant perceptions of which are expected to be the same as those of other EMS Faculty modules. Ethical clearance to conduct this research project was received before commencing the research study.

In aid of the research objective, a separate mentor and mentee survey was employed to acquire the perceptions of these respective participants of the role of the online mentoring programme during ERT. A form requesting participants' consent to participate in this research study was included in the survey. Based on the list of mentors and mentees enrolled in the introductory financial accounting module online mentoring programme for 2020 for the second semester, as received by the head mentor, survey invitations were sent to these students to complete the survey. This form indicated that participation in the research study was entirely voluntary and that the invitees were free to decline to participate. The surveys were delivered electronically via an electronic platform, with links to the survey sent as reminders via email.

Mentor survey

The mentor survey (see Table 1) sought the perceptions of mentors of the role of the introductory financial accounting module online mentoring programme during ERT. The mentor survey comprised four open-ended questions. The responses to the open-ended questions were analysed and grouped according to thematic analysis (Lapadat 2010), which analysed the responses according to themes. An analysis was also conducted via simple narrative content analysis. The mentor survey also included a single checkbox-response question that sought the perceptions of the nature of students who should attend the module mentoring programme, followed by a field for the mentor to document the reason(s) for their response to the checkbox-response question. The mentor survey results were analysed as follows:

• Student mentor perceived value and benefits offered to mentees in online mentoring programme during ERT.

• Additional considerations regarding student perceptions of the online mentoring programme during ERT compared to traditional face-to-face peer mentoring.

The completed surveys generated qualitative data; the results of which were subject to simple narrative content and thematic analyses. Survey responses deemed to be substantially incomplete were removed.

A study limitation is that the enquiry was undertaken at only one university and for one online mentoring programme during ERT and cannot be generalised to other institutions and other online module mentoring programmes. However, the findings offer valuable insight for other modules that offer online mentoring programmes at the university and other institutions, especially during unforeseen disruptive periods such as ERT.

Table 1 provides the survey used to gauge mentor perceptions of the online mentoring programme during ERT.

Mentee survey

The mentee survey (see Table 2) sought the perceptions of mentees of the role of the introductory financial accounting module online mentoring programme during ERT.

The first part of the mentee survey comprised seven open-ended questions. The responses to the open-ended questions were analysed and grouped according to thematic analysis (Lapadat 2010), which analysed responses according to themes. A simple narrative content analysis was also conducted.

The second part of the mentee survey included three checkbox-response questions that, firstly, enquired about the frequency of mentee attendance; secondly, the device access to the online mentoring programme; and thirdly, the perceptions of the nature of students who should attend the module mentoring programme.

The third part of the mentee survey consisted of seven questions that adopted a five-point Likert-type scale to indicate the extent of agreement or disagreement with a particular statement where 5 = strongly agree, 4 = mostly agree, 3 = neutral, 2 = mostly disagree, and 1 = disagree. Each of these questions provided the participants with a field to document a reason for their Likert-scale rating. The mentee survey results were analysed as follows:

• Student mentee perceived value and benefits obtained from attending the online mentoring programme during ERT.

• Additional considerations regarding student perceptions of the online mentoring programme during ERT compared to traditional face-to-face peer mentoring.

Table 2 provides the survey used to gauge mentee perceptions of the online mentoring programme during ERT as well as results of the Likert scale questions.

Sample

The population consisted of all mentors and mentees who had registered for the introductory financial accounting online mentoring programme during ERT for the second semester of the 2020 academic year. The programme transitioned from an in-person mentoring programme and continued online during a period of ERT in the EMS Faculty. It consisted of eight mentors and 102 mentees. Due to the programme continuing online with the transition to ERT in the EMS Faculty, an opportunity arose to compare whether the mainly academic support role of the programme changed under ERT circumstances due to the shift from face-to-face learning to online learning. The response rate for the mentors was 62.5 per cent (five responses out of a total of eight invitations sent). The response rate for the mentees was lower than the response rate of the mentors at 20.6 per cent (21 responses out of a total of 102 invitations sent). The authors suggest that the responses regarding students' perceptions of the role of the introductory financial accounting online mentoring programme during ERT were driven by each individual's circumstantial experience and consequently resulted in a lower response rate. Furthermore, Holbrook, Krosnick, and Pfent (2008) reviewed response rates ranging from 5 per cent to 54 per cent and concluded that studies with a much lower response were often only marginally less accurate than those with much higher response rates. The authors deem the mentor response rate to be sufficient given the study's purpose to source primarily mentor perceptions of the role of the online mentoring programme that they conduct and present. Mentee perceptions of attending the online mentoring programme were secondary.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study received ethical clearance in terms of the institutional requirements of where the study was conducted.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results and discussion section commences with the analysis of the mentors' perceptions and is followed by the mentees' perceptions of the role of an online academic mentoring programme in an ERT environment.

Mentor findings

The mentor survey (Table 1) comprised four open-ended questions that enquired of mentors, firstly, what the main reasons were for them to enrol as a mentor in the online mentoring programme during ERT. The common theme in all the mentor responses was that they wanted to help other students academically with the introductory financial accounting module during online learning. One mentee's response described the perceived role of mentors in a period of ERT:

"When ERT commenced, I realised that this could affect the first years probably the most and they would need extra support. I had always wanted to help people with FinAcc and this year I felt like I needed to."

While the academic subject-specific support domain of mentoring (Crisp and Cruz 2009) is prevalent, the urge to assist specifically during unprecedented times such as ERT reflected and extended a sense of altruistic motivations for mentor support and highlights the importance of the psychological and emotional support domain of mentoring (Crisp and Cruz 2009) during ERT.

The second open-ended question probed mentors regarding what they perceived to be the benefits of the online mentoring programme during ERT for mentees. Two of the mentors believed the small size of the mentoring groups allowed a familiar, trusting, and comfortable space for mentees to ask questions. One mentor participant noted that the mentoring programme provided a space for mentors and mentees as students experiencing the same struggles during ERT. Another mentor indicated the convenience for mentees of being able to attend the session remotely online. These particular responses also fall within the psychological and emotional support domain of mentoring (Crisp and Cruz 2009). These responses are supported by the views of Egege and Kutieleh (2015), who describe peer mentoring engagement as offering a sense of belonging and providing guidance to students who are faced with difficulties, particularly first-year students who are transitioning into higher education. This study highlights to universities offering purely academic mentoring programmes the extended psychological and emotional support benefits of offering online mentoring programmes during a period of ERT.

The third open-ended question probed mentors regarding what role mentors perceive the online mentoring programme to play during ERT. The themed response from mentors describes the role to be that of a peer support system that includes, but is not limited to, academic support. The following mentor response summarises the mentor feedback:

"I think the role of a mentor is to support and encourage their mentees. It is a difficult time and mentees just need to know that there is help available and support, so they do not have to navigate through all of this alone."

The mentor responses indicate the need for supportive communities and academic programmes that incorporate a pedagogy of care beyond academic support (Bozkurt and Sharma 2020) and again highlights the emotional support domain of mentoring (Crisp and Cruz 2009).

The fourth open-ended question probed mentors regarding what the main needs of mentees are that should be addressed by the online mentoring programme during ERT.

Sixty per cent of the mentor responses indicated academic support in terms of exam technique, while 40 per cent of mentor responses indicated the main need to be that of support, guidance, a safe space, and a source of motivation and encouragement from someone mentees can relate to during a difficult period of ERT. While the responses indicate academic support to be the primary need of mentees attending the online mentoring programme, additional non-academic support was also mentioned.

The mentor responses align with the findings of Du Preez et al. (2013), Jackling and McDowall (2008), and Beltman and Schaeben's (2012), who listed the main mentor motivations as altruistic, cognitive, social, and personal growth. The findings of this study regarding an online mentoring programme during ERT support the current literature, which suggests that a peer module mentoring programme provides a whole host of benefits not limited to academic support (Du Preez et al. 2013).

The checkbox-response question in the mentor survey enquired the perceptions of mentors as to the nature of students who should attend the module mentoring programme, to which all mentors responded that the online mentoring programme should be available to any student who wants to attend and should not be based on academic results. This finding regarding the mentoring programme being available not only to students with an academic need suggests that there are additional benefits to be derived from the online mentoring programme beyond academic support (Du Preez et al. 2013; Bozkurt and Sharma 2020).

Noteworthy, unlike Du Preez et al. (2013) findings, none of the mentors listed financial compensation as a reason for enrolling as a mentor, which is consistent with Colvin and Ashman (2010), who found that remuneration is not a primary motivation for mentors.

Table 3 indicates mentors' summarised perceived benefits for mentees of the online mentoring programme during ERT.

Mentee findings

Student support

The first part of the mentee survey (see Table 2) comprised seven open-ended questions:

The first open-ended question enquired as to what the main reasons were for attending the online mentoring programme during ERT. All mentees indicated academic support to be the main reason for attending, while two mentees specifically and respectively noted online learning to be "very challenging" and "a drastic change" and therefore felt that they needed the extra academic support. The responses are in line with the views of Bozkurt and Sharma (2020), who highlight the need for supportive communities and engagement during a period of ERT, notwithstanding additional academic support. Institutions that offer academic mentoring programmes may derive value from continuing to offer online mentoring programmes under changing and challenging institutional circumstances.

For the second open-ended enquiry as to what worked well in the online mentoring programme during ERT, a common themed response reflected that the interactive and real-time nature of the mentoring programme worked well. Academic support and the additional resources offered, such as quizzes and chat sessions, were also identified as working well in the online mentoring programme during ERT. Further to this, a fourth enquiry to mentees sought to determine what forms of additional support were offered by the online mentoring programme during ERT, to which the common themed response was that of additional academic support in terms of resources provided such as notes, examples, revision, explanations, and quizzes. One mentee identified the ability to interact with other students as the additional support provided, while another identified the attention students received in a small group setting and further added the following comment on a specific mentor:

"But even beyond that, she offers us so much additional support, she's very motivating and she really cares and wants us all to do extremely well."

To corroborate the findings above, a sixth open-ended enquiry sought to determine whether mentees would recommend the online mentoring programme during ERT to other students and why. The responses reflected that all mentees would recommend the online mentoring programme during ERT; with most mentees noting the additional academic support as the main reason why they would recommend the programme. Two mentees further highlighted the value of being able to interact with their peers, to whom they can relate, with the following responses:

"Yes. The mentor is very willing and capable to help. They also understand how you feel with regards to online learning as they have to face the challenge themselves too."

"Yes, for students that struggle with online learning - you are able to interact virtually with your peers."

The third part of the mentee survey, which consisted of questions that adopted five-point Likert-type scaled responses to indicate the extent of agreement or disagreement with a particular statement, had the following summarised responses. Most mentees agreed that the online mentoring programme during ERT provides an opportunity to ask mentors questions on the module content as an alternative to asking questions during a traditional face-to-face lecture. In support of this finding, most mentees agreed that during the period of ERT and regarding academic matters, engaging with a student peer mentor was preferred over a lecturer. Furthermore, most mentees agreed that the online mentoring programme during ERT is used as a social platform to engage with other students, which is no longer available because of no face-to-face lectures occurring, which coincides with the perception of mentors who perceive their role to predominantly be that of a peer support role to mentees during ERT. However, most mentees disagreed with the online mentoring programme being used to engage on non-academic related matters, which indicated that mentees attended the ERT online mentoring programme primarily for additional academic support. This response coincides with mentor responses whereby most mentors noted academic support to be the main need of mentees that should be addressed by the online mentoring programme during ERT. Notably, most mentees agreed that the move to ERT required mentors to adapt and provide mentoring based on their own personal and socioeconomic experiences faced during ERT. Most mentees agreed that the move to ERT required mentors to adapt and provide mentoring on adapted study methods for the new online learning environment.

The findings further mention academic support as a primary benefit, as well as the ability to engage with peers on a real-time basis. The hasty nature of ERT may place academic content ahead of student engagement (Bozkurt and Sharma 2020), despite the importance of student engagement in transitioning through higher education and challenging circumstances such as ERT (Egege and Kutieleh 2015). The online mentoring programme during ERT provides insight into the value of student engagement to be added to online mentoring programmes that have a focus of academic support. It can thus be argued that the additional support received from the online mentoring program translates in higher student engagement which advances digital transformation within the ERT environment. Furthermore, it can be argued that online mentoring programs can be used as an intervention to advance pass rates, which in return can contribute to transformation within South African Universities (Ontong, De Waal, and Wentzel 2020).

When posed with the question as to the importance on attendance of an online mentoring program during ERT, 81.0 per cent of mentees believed that any student who wanted to attend should attend the online mentoring programme. Consistent with Du Preez et al. (2013), the mentor findings are aligned with that of mentees, who believed that any student who wants to attend should attend the online mentoring programme on the basis of the programme providing benefits to all students; whether it is to improve marks or to pass. One student's response summarises the consensus of both mentors and mentees:

"Regardless of your marks, it is a very helpful support system, which gives you a better understanding of the work. Thus, any student who wants should attend."

Both mentor and mentee responses reflect that having the mentoring programme available not only to students with an academic need suggests there to be additional benefits to be derived from the online mentoring programme beyond academic support (Du Preez et al. 2013; Bozkurt and Sharma 2020).

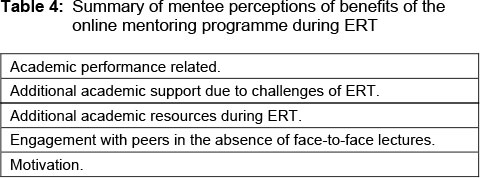

Table 4 presents the summarised perceived benefits by mentees of the online mentoring programme during ERT.

Programme effectiveness

In the third open-ended enquiry regarding what should change in the online mentoring programme during ERT and why, the common themed response was that the online mentoring programme via the Microsoft Teams platform worked well and that nothing needed to change. On the other hand, other individual responses included that the programme could be more interactive through the sharing of screens on Microsoft Teams and more personalised to address the individual needs of students. Overall, the common themed response of a well-functioning online mentoring programme is supported by the literature, which found peer mentoring to be the most effective strategy to increase student retention and satisfaction (Adams et al. 2010).

Programme challenges

The fifth open-ended enquiry questioned why mentees believed that other students did not attend the online mentoring programme during ERT. The responses were mixed and included responses such as students not having proper time management skills, especially with the change to the remote academic environment, as one mentee noted. Other responses included mentees being unaware of the online mentoring programme, mentees not yet being familiar with the work content, or already being familiar with the work content. One particular mentee noted data and Internet connectivity issues (consistent with Lembani et al.'s (2020) findings), lack of electronic devices, home circumstances, as well as lack of motivation as reasons students may possibly not attend the online mentoring programme. Motivation was found to be one of the additional benefits of the peer mentoring programme by Du Preez et al. (2013). Two responses noted that students were not being subjected to the traditional academic environment and with the online learning environment being unregulated, it is easier for students to miss attendance, fall behind, and lack time management skills.

Further to this, for the seventh and final open-ended question, it was enquired of mentees what their greatest obstacle was, if any, in attending the online mentoring programme during ERT. The responses were mixed. Many of the mentees (four out of nine) indicated that they had not experienced any obstacles; with one mentee initially stating the greatest obstacle to be the transition from in-person mentoring sessions to online sessions but that this was remedied after the implementation of Microsoft Teams during online mentoring sessions. Consistent with Lembani et al.'s (2020) findings, seven mentees identified network connectivity as the greatest obstacle. Consistent with Choudhury and Pattnaik' s (2020) findings, one of the aforementioned mentees also included load shedding, which is the term for the rationing of electricity in South Africa (Bohlmann and Inglesi-Lotz, 2021), and living in a remote town as further hampering access to online learning.

Other responses included that the online sessions clashed with formal lecture time slots. The online mentoring session time slots being fixed was also not conducive to the online learning experience where students are able to work at their own pace. This study offers insight into the challenges and benefits experienced by an online mentoring programme during periods such as ERT, from which institutions seeking to offer programmes of a similar nature may benefit.

Additional findings

Additional findings from the second part of the mentee survey, are summarised as follows. The first question, which enquired the frequency of mentee attendance of the online mentoring programme during ERT, with checkbox options always, sometimes, minimal (only before assessments), and minimal (randomly), reflected that 71.4 per cent of the mentees indicated they always attended and 23.8 per cent indicated they sometimes attended the online mentoring programme during ERT. Furthermore, in response to the second question of how the online mentoring programme was accessed, all mentees indicated that they accessed the online mentoring programme using a computer instead of mobile and other device options.

From the findings, one may infer that the traditional peer module mentoring programme before ERT (Du Preez et al. 2013) was rooted mainly in the academic subject-specific support domain of mentoring as identified by Crisp and Cruz (2009). The findings suggest that the online mentoring programme during ERT highlights a shift in the dominance of the mentoring domain of academic subject-related support (Crisp and Cruz 2009) in a traditional peer module mentoring programme and brings to the fore not only academic subject-related support but also the psychological and emotional support domain (Crisp and Cruz 2009). The shift in the dominance of the mentoring domains in the peer mentoring programme during ERT is presented in Table 5.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the suspension of in-person lectures and a swift transition to ERT. The introductory financial accounting online mentoring programme during ERT was a continuation of the previous in-person module mentoring programme. While academic support was the primary function of this mentoring programme, the findings indicate that there are additional perceived benefits of this programme.

This study contributes to the literature of ERT by providing insights to higher education institutions that offer academic online mentoring programmes as to the value of incorporating an ERT-type programme into predominantly academic mentoring programmes. As students have to function primarily online during ERT, additional support beyond the advancement of academic performance is needed to promote the well-being of students. Academic support remains at the forefront of the online mentoring programme; however, with the transition to ERT, many additional benefits have been incorporated into the mentoring programme, which altered the role of the mentoring programme to be inclusive of benefits such as providing a safe, trusting, and familiar space to mentees; peer support for similar challenges experienced during ERT; and encouragement and engagement with peers. Limited research exists on the role of online mentoring during ERT. This study is therefore of importance in providing insights to higher education institutions and the African content as a whole as to the additional value provided by an online mentoring programme during ERT beyond academic support.

REFERENCES

Adams, T., M. Banks, D. Davis, and J. Dickson. 2010. "The Hobsons retention project: Context and factor analysis report." The Hobsons retention project (October): 1-32. http://aiec.idp.com/uploads/pdf/2010_AdamsBanksDaviesDickson_Wed_1100_BGallB_Paper.pdf. [ Links ]

Ajoodha, R., A. Jadhav, and S. Dukhan. 2020. "Forecasting Learner Attrition for Student Success at a South African University." ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 19-28. [ Links ]

Beltman, S. and M. Schaeben. 2012. "Institution-wide peer mentoring: Benefits for mentors." The International Journal of the First Year in Higher Education 3(2): 33-44. [ Links ]

Bohlmann, J. A. and R. Inglesi-Lotz. 2021. "Examining the determinants of electricity demand by South African households per income level." Energy Policy 148(PA): 111-901. [ Links ]

Bozkurt Aras and Ramesh Sharma. 2020. "Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to Coronavirus pandemic." Asian Journal of Distance Education 15(1): 1-6. [ Links ]

Broos, T., M. Pinxten, M. Delporte, K. Verbert, and T. De Laet. 2020. "Learning dashboards at scale: Early warning and overall first year experience." Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 45(6): 855-874. [ Links ]

Choudhury, S. and S. Pattnaik. 2020. "Emerging themes in e-learning: A review from the stakeholders' perspective." Computers and Education 144(September 2019): 103657. [ Links ]

Collier, P. 2017. "Why peer mentoring is an effective approach for promoting college student success." Metropolitan Universities 28(3). [ Links ]

Colvin, J. W. and M. Ashman. 2010. "Roles, risks, and benefits of peer mentoring relationships in higher education."Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 18(2): 121-134. [ Links ]

Crisp, G. and I. Cruz. 2009. "Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007." Research in Higher Education 50(6): 525-545. [ Links ]

Du Preez, R., L. P. Steenkamp, and R. S. Baard. 2013. "An Investigation Into A Peer Module Mentoring Programme In Economic And Management Sciences." International Business & Economics Research Journal (IBER) 12(10): 1225. [ Links ]

Egege, S. and S. Kutieleh. 2015. "Peer mentors as a transition strategy at University: Why mentoring needs to have boundaries." Australian Journal of Education 59(3): 265-277. [ Links ]

Gunn, F., S. H. Lee, (Mark) and M. Steed. 2017. "Student Perceptions of Benefits and Challenges of Peer Mentoring Programs: Divergent Perspectives From Mentors and Mentees." Marketing Education Review 27(1): 15-26. [ Links ]

Hodges, C., S. Moore, B. Lockee, T. Trust. and A. Bond. 2020. "The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning." Educause Review: 1-15. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning. [ Links ]

Holbrook, A., J. Krosnick, and A. Pfent. 2008. "The causes and consequences of response rates in surveys." In Advances in telephone survey methodology, ed. J. M. Lepkowski, C. J. Tucker, M. Brick, E. Leeuw, L. Japec, P. J. Lavrakas, M. W. Link, and R. L. Sangster. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. [ Links ]

Jackling, B. and T. McDowall. 2008. "Peer mentoring in an accounting setting: A case study of mentor skill development." Accounting Education 17(4): 447-462. [ Links ]

Lapadat, C. 2010. "Thematic analysis." Encyclopedia of case study research (2):925-927. [ Links ]

Lembani, R., A. Gunter, M. Breines, and M. T. B. Dalu. 2020. "The same course, different access: The digital divide between urban and rural distance education students in South Africa." Journal of Geography in Higher Education 44(1): 70-84. [ Links ]

Lowery, K., R. Geesa, and K. McConnell. 2018. "Designing a peer-mentoring program for education doctorate (EdD) students: A literature review." Higher Learning Research Communications 8(1): 30-50. [ Links ]

Lunsford, L. G., G. Crisp, E. L. Dolan, and B. Wuetherick. 2015. Mentoring_in_ Higher_Education_BK_SAGE_CLUTTERBUCK, 316-334. [ Links ]

Ontong, J. M. and A. Bruwer. 2020. "The use of past assessments as a deductive learning tool? Perceptions of students at a South African university." South African Journal of Higher Education 34(2): 177-190. [ Links ]

Ontong, J. M., T. de Waal, and W. Wentzel. 2020. "How accounting students within the Thuthuka Bursary Fund perceive academic support offered at one South African university." South African Journal of Higher Education 34(1): 197-212. [ Links ]

Sinwell, L. 2019. "The #Fees Must Fall Movement: 'Disruptive Power' and the Politics of Student-Worker Alliances at the University of the Free State (2015-2016)". South African Review of Sociology 50(3-4): 42-56. [ Links ]

UNISA see University of South Africa.

University of South Africa. 2022. "Student Mentor Programme." https://www.unisa.ac.za/sites/myunisa/default/Learner-support-&-regions/Counselling-and-career-development/Plan-your-career/Student-Mentor-Programme. (Accessed 24 June 2022). [ Links ]

World Health Organization. 2020. Who Emergencies Press Conference on cornavirus disease outbreak, 11 March 2020. [ Links ]

WHO see World Health Organization.

York, T. T., C. Gibson, and S. Rankin. 2015. "Defining and measuring academic success." Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation 20(5): 1-20. [ Links ]

Yorke, M. and L. Thomas. 2003. "Improving the Retention of Students from Lower Socio-economic Groups." Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 25(1): 63-74. [ Links ]