Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.36 n.2 Stellenbosch May. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/36-2-4718

GENERAL ARTICLES

South African student leadership unrest and unsettled constructions: a CIBART analysis

N. Pule

Department of Psychology University of the Free State Bloemfontein, South Africa http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0668-1172

ABSTRACT

Student leadership in South Africa is unsettled and characterised by unrest. The perturbing changes in the higher education system, including global shifts and crises, impact South African student leadership psychologically. Consequently, this article seeks to understand the system psychodynamics of South African student leadership. Data was collected during a social dream drawing (SDD) session with student leaders at a South African university before the onset of the Fees Must Fall movement. The SDD session aimed to understand the social construction of student leadership at a South African university and data was analysed through discourse analysis with a psychodynamic interpretation. For this article, a co-reflector was incorporated for secondary analysis after Fees Must Fall to reorganise, reinterpret the data and enhance the initial findings using a conflict, identity, boundaries, authority, role, task (CIBART) model. CIBART findings show that students have a need for a collective and shared vision, and find it unsettling when this need is not satisfied due to the complex environment. Thereby, their psychological safety is threatened, while anxiety is heightened in an environment characterised by transformation and decolonisation agendas. Substantial conflicts impact authority dynamics while, simultaneously, student leadership identity and boundaries are blurry and in crisis. Thus, the compromised clarity of student leadership elevates implications for the confidence that is required for the role and task of student leadership. Consequently, efforts to reduce the anxiety of student leadership ought to be a priority. Psychologists are indicated to play a crucial role in restoring the psychological safety and security of student leaders.

Keywords: CIBART, diversity dynamics, social dream drawing, student leaders' anxiety, system psychodynamics

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Student leadership can be described in various terms (Getz and Roy 2013; Luescher-Mamashela 2013; Griffiths 2019). In this article, student leadership is understood as a system consisting of a complex constellation of subsystems (i.e., political organisations, campus leadership structures, etc.) within the broader higher education system in South Africa. Agazarian (2012a) helps us to articulate student leadership as the individual system (i.e., the individual student leader), the member system (respective student leadership structures, e.g., student representative council (SRC), residence committee, student culture committee), the group as a whole (student leadership community per university or collectively across universities) and the transitionary space (otherwise called subgroups, which can be defined by diversity characteristics, such as race, gender, social class, university affiliation, course of study, etc.). These subsystems form the parts of the student leadership system that, in this article, we seek to understand mainly psychologically, thus, through a system psychodynamic lens.

To understand the reactions, emotions and motivations of the system of South African student leaders psychodynamically, a Conflict, Identity, Authority, Boundaries, Role, Task, i.e., CIBART, model was used. The intention to highlight South African systems (with reference to student leaders) is supported by Fanon, who insists on historically grounded terms when analysing psychological observations (Hook 2004a). Agazarian (2012a) adds to this notion by referring to the importance of context for understanding systems, to the extent that an understanding of the system cannot be separated from its context. More specifically, though, Fanon cautions about the dangers of generalising psychological analysis, particularly in relation to the socio-political (Hook 2004b).

Student leadership context

Structurally and legislatively, student leadership is identified by South Africa's Higher Education Act 107 of 1997 (Republic of South Africa 1997). Beyond this act, there are other student structures, such as student tribal councils, faculty committees/student academic committees, residence committees, political parties and other student clubs for student rights, cultural and social activities and so on, within which student leaders occupy leadership roles. Furthermore, students are prepared for the workplace through university programmes that develop their leadership skills, resulting in their categorisation as student leaders (Getz and Roy 2013; Mukoza and Goodman 2013). Additionally, student activists or students who are involved in activism activities are recognised as student leaders due to their high degree of passion for a cause (Swartz et al. 2019) and ultimate stimulation of the higher education climate or operations (Griffiths 2019).

Over time and since the transformation of higher education in post-apartheid South Africa, student leadership at South African universities has undergone major changes (Jansen 2003; Singh 2015; Swartz et al. 2019). Initially, the changes and shifts resulted from mergers, and contentions around admission for and access by diverse student population groups to the space (Cross 2004; Cross and Carpentier 2009; Waghid 2003). Additionally, the shifts were marked by acculturation tensions and transformation drives, including indications of massification of the higher education space (Cross and Carpentier 2009; Jansen 2003; 2018; Niemann 2010). Later, the Fees Must Fall movement and recent other, similar student movements (Griffiths 2019; Jansen 2018; Swartz et al. 2019) heralded more changes and radical appearances of student leaders. Furthermore, the inevitable impact of global shifts and internationalisation effects, such as the fourth industrial revolution, add to the complexity of higher education today (Butler-Adam 2018; Xing and Marwala 2017). These changes and shifts in student leadership have been characterised by unrest and a degree of unsettledness, denoting a psychological impact (Albertus 2019) that can operate below the surface (Clarke and Hoggert 2009). Psychodynamically, unrest is a result of splitting defences after identity insecurity, by which an "us and them" narrative is encouraged, or an ingroup/outgroup phenomenon, to promote a sense of self-coherence and wellbeing through a quite inflexible way of thinking (Akhtar 2018). The desire for unrest caters to protect the ingroup from the unwanted and "bad" characteristics that are projected on the outgroup, toward maintaining the "good" character of the ingroup. Accordingly, systems spend energy defending themselves from anxiety, by using defence mechanisms that may vary in reactions (Cilliers 2017). Driving forces propel the system toward positive development, while restraining forces constrain the system's growth (Agazarian 2012a).

System psychodynamics and CIBART

System psychodynamics is dedicated to understanding the below-the-surface behaviour of organisations and systems. Therefore, it makes behaviour assumptions, which include dependency, fight/flight, pairing, oneness and we-ness; and me-ness (Koortzen and Cilliers 2005; Oosthuizen and Mayer 2019). Furthermore, the orientation focuses on the interrelationships between psychological and organisational boundaries, which may involve group process, issues about roles including culture (Mayer et al. 2018). System psychodynamics, finally, explores unwanted feelings and experiences by focusing on the dynamics of splitting off, and projected parts of the system (Koortzen and Cilliers 2005).

Within system psychodynamics, therefore, student leadership as a system comprises dynamics of a psychological nature, which could be understood as operating consciously and unconsciously. The CIBART model is one way of understanding the functioning and development of systems, thus, their dynamics. The model is used to explore and explain organisational phenomena regarding organisational members' experiences, system psychodynamically (Mayer et al. 2018). In the CIBART model, C represents conflict, I identity, B for boundaries, A represents authority, R role and, lastly, T for task (Koortzen and Cilliers 2005). These constructs are interrelated, and facilitate the exploration of intrapersonal, interpersonal and intergroup dynamics (Koortzen and Cilliers 2005). More specifically, therefore, the CIBART model gives this article a structured method to contain and explain the complexity of student leadership through specific terminology.

METHODOLODY

Research approach and design

Consequent to the above, this study was framed within the psychosocial paradigm. Psychosocial studies foreground the interconnections between individual and group identities (i.e., student leadership in South Africa, in this case), including the historical and contemporary social and political formations of student leadership (Frosh 2019). Furthermore, qualitative research in a case study design was employed. The case study is of a social dream drawing session (SDD) that was conducted with student leaders at a South African university. The design is pluralistic (Chamberlain et al. 2011), given the employment of a co-reflector for secondary analysis using a system psychodynamic CIBART lens to interpret data that had already been analysed psychosocially.

Data gathering

To gather data, a SDD session was conducted with six student leaders at a historically white university (HWU) (Pule 2017). The group consisted of SRC members, SRC subcommittee members, student tribunal members, and members of an international student leadership exchange programme.

SDD is indicated as a highly effective data collection method in institutional research (Mersky 2013), as it helps participants to identify and explore underlying systemic dynamics that derive from new thoughts and shared understanding of their organisational reality (Mersky and Sievers 2019). These associative insights develop by linking respective participant drawings with one another and themes emerging (Mersky 2013). Dream material is generative, thus, the drawings are documentaries of social and organisational experiences that can be analysed from different perspectives at different points in time (Mersky and Sievers 2019).

During the SDD, student leaders were asked to present a dream drawing based on the primer, "My dream of student leadership", which was provided prior to the session. Dream drawings were presented by respective participant one at a time. After each dream drawing presentation, free associations and amplifications were made by the group (Mersky 2015), such that the group's associative unconscious (Long 2013) emerged. Afterwards, a process of collective knowledge creation was engaged wherein new thoughts about student leadership emerged and sense-making about the social context from the perspective of student leaders occurred (Lawrence 1998). Each dream drawing was allocated an hour. Data was captured by means of text that was derived via a voice recording and field notes, as well as photographs of the dream drawings.

Data analysis and rigour

Through using a system psychodynamic lens to focus on the underlying psychological dynamics of the system of student leadership, themes about the reactions, emotions and motivations of student leaders were extracted using the CIBART model. On a previous occasion (Pule 2017), a fusion of discourse analysis and psychodynamic interpretation was used to analyse the data. For this article, a CIBART model was used to reorganise the interpretation and the reporting of the data to enhance the initial findings; leading to new themes being derived.

The secondary analysis involved the incorporation of a co-reflector. Including a co-reflector enhanced rigour, especially pertaining to the credibility and trustworthiness of the secondary analysis. The co-reflector made it possible for the primary author to take a more distant view, after the primary author had worked closely with the data in the initial data analysis process. Accordingly, the co-reflector cast a fresh eye on the data, as someone newly engaging with the data, and also presented a new perspective in relation to the primary author's prior analysis.

Both analysts, at different points of time in history, were students and student leaders at the university at which the data had been gathered. The analysts brought differing positionality regarding their race, gender and perspective of student leadership, while and since they themselves had been student leaders at the same university where data was collected. Their positionality resulting from their perspectives on student leadership can also be based on the subjectivity they hold, especially regarding the informal authority they experienced while they were students and student leaders. Additionally, their positionality in this analysis could be the result of the informal authority that has been imposed by the current socio-political-psychological transformation of South African universities, and higher education in general. Characteristically, the primary author is black and female, while the co-reflector is white and male. Thus, beneficial to rigour, the analysis team contributes wide representations to the interpretation, that yielded rich, resonating, current and historical socio-cultural-political-psychological positions. Equally, rigour was enhanced further by the reflection and reflexivity perspectives (Valandra 2012; Yang et al. 2020).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethical clearance was sought from the relevant institutions and permission to collect data was granted by the appropriate Student Affairs department. Participation was voluntary such that participants could withdraw at any time. Confidentiality and anonymity is assured as the analysis involved group knowledge creation rather than individual opinion. Dream drawings are identified by a number rather than being linked to the participants' identity, since the dream content discussed represents the collective unconscious. Participants have signed consent forms and were provided session and research process information sheets prior to the data collection.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The findings are reported according to the different elements of the CIBART model, namely, Conflict, Identity, Boundaries, Authority, Role and Task. Thereafter, an integration of the CIBART analysis is provided.

Conflict

Groups require energy to function or develop, which the system uses to organise itself (Agazarian 2012a). Accordingly, conflict can be organisational or system energy source (Oosthuizen and Mayer 2019). This energy results from experiences of system functioning anxiety that is of an unconscious nature (Mayer et al. 2018). Anxiety shows up in the form of defences that are used to manage fight-or-flight states where scapegoating, projections and so on play out (Agazarian 2012b; Kohut 2004). Consequently, conflict denotes the splits that occur within the self, between self and others, and inside and between groups.

In student leadership, conflict is characterised by splitting dynamics, which result in the formation of in-groups and outgroups through the us-and-them discourse, as discussed by Pule (2017). Within the member system, a hyper-concern for group cohesion is observed, based on the student leaders' desire for functionality, so that they can integrate their differences. Group cohesion also appears to be an unconscious strategy to maintain and sustain the in-group within the member system. Akhtar (2018) notes that the formation of an in-group facilitates the process of securing an identity in a way that expels the unwanted and hated traits of the system into the outgroup. Simultaneously, the in-group needs the outgroup to foster a sense of psychological safety in the system. Student leaders, therefore, unite through obstacles experienced in the role. These obstacles allow student leaders to spend time complaining to management and related persons about common concerns including meetings and strategising about the obstacles experienced in student leadership. However, competition within the member system demarcates stereotype functioning, which is usually defined by race, gender, seniority and perceived student leadership authority. The us-and-them discourse, thus, denotes the scapegoating phenomenon that is linked to the fight-or-flight phase of group development (Agazarian 2012b; Hook 2004b). The most profound observation could be that the diversity and the diversity dynamics explained by Pule (2017) fuel anxiety (that can be thought of as a restraining force) within the student leadership organisation, to such an extent that anxiety becomes the driving force and system energy.

The dream drawing in Figure 1, titled the half-face dream, and which is supported by the quotation that follows, highlights the us-and-them split. The drawing also refers to identity issues - identity as student leaders vs. identity as students - as discussed later in this article.

The following comment about the half-face dream refers to the discussion above:

"One thing that I pick up about this is that there's a common critique I think sometimes that student leaders don't stand together often enough and I think we don't fight for each other often. I'm not saying it's us against the students, because we are the other half of the face, you know what I mean, we are them. But I think that we don't stand with each other for the major issues, you know, and I think when that happens, like she says, there's obviously a whole lot of shots fired and I think that's the image I get is that the student leaders who need some form of common vision, ... and we know what the key issues are and that's what we're going for in our very different ways. And I mean, we don't have that. We definitely don't have it."

Evident rivalry about race and gender issues, and the approach used to address these issues, is observable, and shines a spotlighting on trust and mistrust dynamics. The group agrees that their intention is to pursue Ubuntu. Ubuntu is an African life philosophy that espouses interdependence and solidarity among human beings (Nwoye 2017). The student leaders describe Ubuntu as a selfless leader, who seeks peace, and is accommodating as in the following quotations:

"So it's being a selfless leader, not thinking about yourself, putting yourself in any kind of position to, how can I say, to accommodate others."

Another student leader said the following:

"I also get this feeling of like old-school leadership, like non-fighting with the guns like Ghandi, you know, kind of stuff, Mandela."

Simultaneously, differences or split in approaching conflict appear as either a peace-making approach (displayed as a passive or passive-aggressive approach), or an aggressive or confrontational approach (displayed as overt aggression, at times used to express a sense of agency). The latter could be associated with movements such as Fees Must Fall.

Fanon's theory of racism and identity assists us to rethink the concept of violence and, in our paraphrase, aggression/aggressive expression (used to express agency), as indicated above. This conceptualisation denotes that the very act of racism and structural division during apartheid is, in fact, violence (Hook 2004a). Thus, one's assumption of the character of violence is motivated by the desire to instil human agency, as a way to free oneself from oppression. Through collective catharsis, those who have experienced alienation exert certain forms of aggression that are channelled outwards, to release the psychological burden of oppression (Hook 2004b). For those (previously) colonised, the events may not necessarily have been experienced, but can be fantasised about, hence, the applicability of this explanation in a postapartheid era. This means that, through generational trauma and internalised oppression, previously oppressed people and their oppressors could repeat patterns of old, probably in different ways. Racial grouping, for example, arises from the need to deal with feelings of guilt that emerge from acts of injustice the other has been subjected to, resulting in anxiety within student leadership. A student leader's comment demonstrates this argument:

"[In residence committee leadership] the fights are not always that big because you're only concentrating on one aspect. One thing that got very, very challenging on the SRC is that, now you guys have to do everything and sometimes you can't even get your colleagues to agree on something as, how do we deal with a racism incident on campus and some people are like, 'let's not deal' and then we're like, 'we can't not deal'. That's also what gets really frustrating. It's not just the person who doesn't want to sign or the person who gives you the word 'no' or the person who says, 'no you can't have your peaceful walk to the admin building for this'. It's also then the people that you are working with as well and if your guys are like in synergy - and it's almost impossible for you guys to all be on the same page so you will fight. And then when you do fight it's like, okay

Identity

Identity within the system provides members with feelings of belonging, including a sense of hope and mastery, rather than helplessness (Mayer et al. 2018). Diversity markers, particularly generational belonging, language, race and gender, contribute to identity creation (May 2012; Oosthuizen and Mayer 2019). Regarding leadership, Koortzen and Cilliers (2005) advise that identity delineates what the individual leader stands for and embraces what is situated within a leader's own (individual system) boundary.

Thus, issues of conflict, as discussed above, relate to identity, and involve the need for recognition vs. feeling unappreciated during student leaders' battle with an identity crisis regarding their leadership position and their sense of belonging as students. At times, student leaders speak of "the students'", as if they are not students themselves, but then, they would also remind themselves, "Another thing I think of is as student leaders, most of the time we forget that we are students."

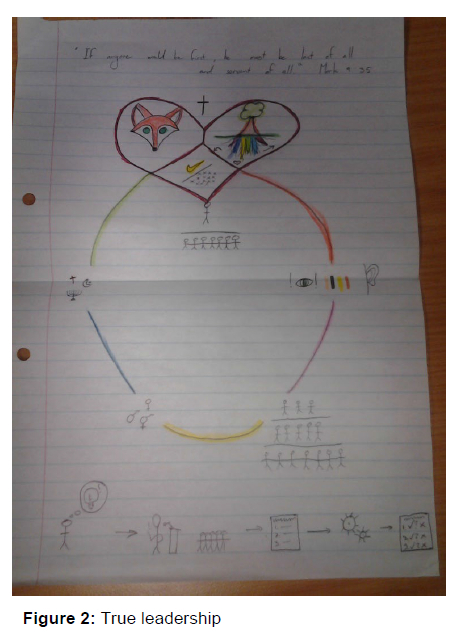

This identity crisis pertains to student leaders crossing the boundary of the student leadership system to join or identify with the constituency, aiming to drive agendas/philosophies they identify with at the individual system level. In this study, student leaders referred to Christianity as a benchmark for attributes of true leadership, due to Christianity's association with selflessness and a sacrificial posture (martyrdom), which emerged from the dream drawing in Figure 2 (Pule 2017).

The identity crisis is viewed as both a projection and an introjection, as evidenced by this quotation:

"In the same way that when you regard yourself separate from the student body, they do the same thing as well. They never look at you as someone who is like them and sometimes I think when we're doing stuff it feels like, if someone let's say at forum, sort of gives the suggestion of what the SRC should be doing and you're just then thinking, does this person think I don't go to class at all? Like I chill the entire time and this is what I'm doing all day, every day. I don't know where the issue is with the idea that we don't recognise student leaders as part of the people and the thing is, when we speak of student life and we're speaking why people that are struggling with finance is someone on the SRC struggling with finance. And we just think they're so like experienced in the entire thing and you get so disconnected to the people that you're serving."

The crisis, and the crossing of boundaries breeds disappointment regarding expectations of camaraderie within the organisation, and questions about the best way to approach getting support from outgroups, including the student constituency. The student leadership experience is, thus, marked by loneliness and feelings of rejection, relating interpersonal challenges in the member system and group-as-a-whole to support and disagreement. Additionally, student leaders experience a tension based on their somewhat betrayal of the student community by admitting to receiving "special" treatment from university management. The tension results because admitting things make them real. It is, therefore, beneficial for student leaders to remain in denial about their intrapersonal needs, so that they can find psychological safety and security in the student community. However, issues remain unresolved. According to student leaders and literature (Jansen 2003; Mukoza and Goodman 2013; Singh 2015; Swartz et al. 2019; Waghid 2003), the issues that remain unresolved are transformational issues, student governance issues and personal development issues, for example; that relate to making the most of the leadership opportunity. Consequently, student leaders experience conflict (internally and with others) about whose agenda to implement, or which system goal to meet in relation to parts of the system (Pule 2017). It is noteworthy to consider the clash between development of self vs. the development of the group or system. Agazarian (2012a) explains that, since roles are linked to goals, the goal of the individual system is self-development, while the goal of the member system may, for example, be group development. Thus, student leaders' identity crisis can be explained by a clash between role and goal, because of having to perform at various levels of the system simultaneously, which present competing interests.

A student leader said the following in this regard: "I see myself as someone who has her fingers stuck in way too many jellies."

The reference to jelly lead the co-reflector to thinking of another aspect of "being a student", that is, the carefree, naughty, having-fun part. Many students enjoy this part of being a student to the fullest, while student leaders often miss out on the fun, because they are burdened with responsibilities.

Boundaries

Theoretically, boundaries define the group structure by indicating what is included in and excluded from the system (Mayer et al. 2018), including the space between the parts of the system, i.e. the individual, the interpersonal relationships and the interconnections between group members (Koortzen and Cilliers 2005). Agazarian (2012b) suggests that a balance between driving and restraining forces keeps the system stable. Therefore, for members of the system, boundaries provide a space for protection and containment. Accordingly, safety, clarity, control and trust are cultivated. Without boundaries, members may feel lost and experience loss of relationships, or become relationally disconnected due to ambiguous information and confused messages.

To define group boundaries and to conform to the status quo, student leaders in this study took a socio-politically and historically informed stance of the South African story. The status quo includes the entrenched institutional culture and likening student leadership events to South Africa's apartheid and post-apartheid events. This stance incorporates acknowledging differences at unconscious and conscious levels, including awareness of the presence/existence of different kinds of students on a spectrum of varying privilege relating to political-historical position, economic privilege, university exposure for themselves and of family members, etc. These and other factors make the university experience easier or more difficult for a student leader, depending on their position on the spectrum of privilege.

In Fanon's theory, this phenomenon may appear in, for example, scapegoating, when blame is projected as a means of avoiding guilt about the injustice the other has been subjected to, while the other takes a phobogenic position (Hook 2004b). The space between parts of the system, thus, occurs to be a bleak South African status, which is described by student leaders as a South Africa that is in a sad place of despondency, "where the rainbow does not shine".

Authority

Authority in the CIBART model is characterised by formal and informal authority. Formal authority is referred to individuals with recognised competence to perform certain roles (Mayer et al. 2018) whereby their authority is legitimised by boundaries set by the organisation (Oosthuizen and Mayer 2019). This authority is similar to that of student leaders who are elected in accordance with the Higher Education Act, which prescribes the election of members of a representative body or a governance structure involved in the decision-making processes of the university (Luescher-Mamashela 2013). Thus, formal authority in student leadership is assigned by the hierarchical organisational structure, which begins with the Higher Education Act. At respective universities, this organisational structure is headed by the university principal, which could, sometimes, be in tension with the president of the SRC, as per the Higher Education Act's articulation of the role of the SRC. Student affairs departments and deans of students or directors of student affairs are also part of this web of authority. Therefore, the complexity of the formal authority arises on account of agency or self-authorisation, which is part of the construction and foundation of the informal authority of student leadership. Therefore, informal role is intra-person-motivated (Koortzen and Cilliers 2005), thus, represented by the individual system, and operates outside formal authority, meaning that it can be offered or withheld at any time.

Concerning formal vs. informal authority, student leaders take on a leadership burden that blurs the lines regarding where their responsibility begins and ends. Consequently, martyrdom that has a sacrificial flavour becomes the order of the day. Student leadership identity issues, as discussed earlier, are entrenched. Issues regarding the leadership burden seem to be linked to concerns about making a mark, although student leaders recognise themselves as rebels without a cause (Pule 2017). The following comments demonstrate these sentiments.

"You can't. You can't live with that. And I think as well, what's crippling about the realisation that you can't get everything done is the idea that this big plan that you had, you probably had it because you noticed that something was the matter and it's not only the fact that you couldn't get it done, but it's that you couldn't even solve the problem if you planned it to solve a problem in the first place."

Student leader 1: "Mandela is gone but now we need to find something. We need to keep fighting as you were saying, as the youth we are just fighting and we don't know what we are fighting for, but we are fighting."

Student leader 2, in response: "Rebels without causes." [laughing]

Role

Consciously and unconsciously, different roles are assumed when they boundaries between one part of the system and another are crossed (Agazarian 2012b). Thus, a role is based on the extent and the type of authority one holds in the organisation (Mayer et al. 2018). Due to a role being linked to system goals (Agazarian 2012a), student leaders take up roles in relation to the part of the system from which they are performing at a certain point in time. Roles can be normative, existential, and phenomenal (Koortzen and Cilliers 2005). A normative role would be occupied by student leaders currently in office, as this role indicates the explicit content related to the position of student leadership. The existential role may be indicated by previous student leaders, given their past experiences when serving as student leaders. This role could also be assumed by students who aspire to hold the normative role of student leadership, i.e., those who may have contested elections in the recent past or those who would have liked to contest the election. Lastly, the phenomenal role is explained by projections of students who are not indicated for student leadership. Oosthuizen and Mayer (2019) advise that incongruence between roles creates space for anxiety and poor performance in the student leadership task.

Student leaders' roles (formal and normative) are established within the rigidity of the prescriptions of the allocated portfolio or student leadership group (or subgroup) focus. Hereof, tensions can be observed between the individual and the collective contribution. Consequently, due to the hierarchical structures, the normative, existential and phenomenal roles become complicated. Incongruence leaves student leaders anxious and performing poorly within the student leadership task.

In the normative role, student leaders have the limited time of a one-year term of office per interval. Existentially, leaders are obsessive and possessive about the status/accolade that is linked to the role, as illustrated by the feeling associated with the wearing an SRC blazer or similar insignia. As mentioned, leaders connect with their respective constituencies through agendas established within their own individual system. The phenomenal role of student leaders is aspirational. The aspirations include times both during the occupation of the role, and while in contemplation of assuming the role which student leaders bring into the normative role. Student leaders' comments demonstrate the latter in the following manner:

"You find someone who sees vision in you and tells you that, I will nominate you. And then you start getting your own little dreams about, yes, if I get elected this is what I'll do or I will do this."

"[One is] full of all these ideas, all of this stuff that you want to achieve and then you may not have achieved a lot of them or any of them or some of them."

In the quest to reach aspirational fulfilment, student leaders take on martyrdom, which is additionally demonstrated in student leadership identity and authority. Hypothetically, they are ready to lead like Mandela (in the mind) who took a sacrificial leadership role, against all odds and in the face of imposed or perceived barriers. This idea is signified by the Christian cross in the dream drawing in Figure 2 wherein "true leadership" emerged. Associatively, the cross, or Christianity, may refer to the "ultimate authority". Mutually, it may also indicate a yearning to connect across the us-and-them divides, considering the strong shared belief system of Christianity. Actually, if one part of the cross is us and the other is them, the connection of the two elements makes the cross complete when the two parts meet in a common place called Christianity. Accordingly, Christianity offers something beyond religion; it offers a place of belonging and identity, or predictable behaviour that implies that people can trust one other, or rely on each other, because one can predict the other's next step in the role of leadership, if it is based on Christianity.

Task

The task of student leadership refers to the performance criteria or role content (Oosthuizen and Mayer 2019). For student leaders who are in their roles based on the Higher Education Act and governance-related requirements, the task of student leadership is clear and prescribed, which means the primary task of student leadership is unambiguous. For other student leaders, particularly those in the informal authority spectrum, or outside election in accordance with the Higher Education Act and other requirements, the task of student leadership is formally undefined. Consequently, the primary task of the organisation of student leadership as a whole (or group-as-a-whole) is, thus, marred by confusion or unclarity.

The perceived student leadership role, expectations of the student body, a personally driven agenda of student leaders, and other activities, such as student or residence culture activities indicates the secondary task and occurs within the formal and informal roles of student leadership. By definition, the secondary task can take the form of anti- and off-task behaviour. This behaviour is characterised by free-floating anxiety, which prevents role performance and means the student deviates from or derails the primary task behaviour (Cilliers 2017) and, therefore, acts as restraining forces (Agazarian 2012b).

Student leaders identify their primary task through a shared vision rather than strictly legislative guidelines. Consequently, preoccupation with secondary tasks, as well as anti- and off-tasks that occur intra-psychically within and outside the student leadership organisation naturally becomes a deterrent. Feelings of loss regarding individual-system-aspired agendas that respective student leaders have before entering student leadership consume a great deal of task space in the performance of the role. Consequently, student leaders seem to carry a sense of grief during their term of office, because of a preoccupation with unrealised dreams (Pule 2017). For them, the sense of failure is a dominant secondary task which appears to be driven at an intra-psychic level. A sense of despondency accompanies the loss feelings. Collectively, a single task is experienced as disappointing, and this disappointment shows itself as anti-task behaviour. Additionally, student leaders are preoccupied with a sense of fear of new opportunities, and tension caused by feeling unseen, as evidenced by the half-face dream drawing (Figure 1). It appears that most of the collective (or group-as-a-whole) preoccupation is related to anti-task behaviour. Furthermore, other characteristics of this anti-task behaviour include needing recognition, fear of being forgotten and reputation focus. Ultimately, student leaders appear to be busy, though they also do not seem to achieve their primary task, because of a hyper-focus on anti-task behaviour which occurs in group-as-a-whole.

Student leaders also seem to engage in the secondary task of searching for support, as well as the anti-task of feeling rejected and working with the mould to fit into. Consequently, on an intra-psychic level, the anti-task relating to the tension between the fantasy of and about student leadership vs. the reality shock, is given attention. Anxiety about meaning in life, fantasies about student leadership, as well as failure, take centre stage in the form of the off-task behaviour. Essentially, student leaders entertain the anti-task relating to the introjected negative schemas regarding their identity as ideal leaders. Consequently, a discussion regarding the task of student leadership magnifies the significant contribution psychologists can make concerning the mental health of student leaders.

Summary of findings

The anxiety in the system of student leadership cultivates an environment that is characterised by tensions. Without a "manual" for student leadership practice, student leaders feel lost; because of the leadership burden. Consequently, a need for structure for the formal role is sought after for experiencing safety within existing structures. Regarding psychological safety, from a cultural diversity perspective, Black student leaders tend to feel unsafe in an HWU, while White student leaders feel unsafe in an environment characterised by a transformation and decolonisation agenda, which changes the HWU that is meant to be familiar. When the complexity of the situation causes student leaders to fail to achieve a collective and shared vision, they find it unsettling. Importantly, student leaders fear failure, the future and success. Regarding identity, therefore, martyrdom and leading by example, or being looked up to becomes the ideal leadership identity. In debating their own competence and feelings of confidence about being (en)trusted by their respective constituencies as trustworthy enough to occupy leadership roles, student leaders are conflicted about admitting their need for mentorship or leadership development. This conflict is partly because those who would provide such development activities are successfully defined as being in the outgroup. The outgroup, in this case, may include university management, such as student affairs practitioners and management, other groups, such as senate, the university council and the university principal's office, and previous student leaders and previous students (usually referred to as "ou manne" [the old men]). Consequently, the system becomes abundant with free-floating anxiety. Accordingly, the managing of change in the student affairs context has been examined by researchers such as Lumadi and Mampuru (2010). In this article, the consolidated CIBART analysis shows the complex psychological work and investment involved in student leadership. This complexity calls for a contribution by psychologists, particularly for addressing the mental health of student leaders.

Simultaneously, student leaders seem to be preoccupied with birthing new or pioneering tangible results, possibly to achieve the opposite outcome from the rainbow that does not shine, as a student articulated. The quotations below present these sentiments more clearly.

"some people birth new things and student leader X about transformation and radical change and so forth. And all these things are important. You can't say one's important and the other not, they're all important. So it is cool to hear that again, but also to divert the problem and see the child clearly that next year we have a baby know and the baby must be raised in a certain way and everyone must be

CONCLUSION

This article seeks to advance and enhance SDD findings of Pule (2017) that were initially obtained from discourse analysis with a psychodynamic interpretation, in an attempt to understand the system psychodynamics of student leadership at a South African university. The aim of the article was achieved by applying a CIBART model of analysis. Jointly, the primary author (who was involved in the initial analysis) and a co-reflector, (who was new to the analysis), yielded new analysis and findings. The reflexive outcomes in the approach contributed rigour to the CIBART analysis. Additionally, the analysts' static diversity factors and positionality resulting from their previous student leader roles at the same university where data was collected, contributed to the richness of the analysis.

The CIBART findings reveal unrest in, as well as unsettled South African student leadership constructions. These findings show that substantial conflict dynamics are prevalent in the student leadership system, with a theoretically unsurprising effect on authority. Therefore, student leadership identity and boundaries within the system are in crisis and appear to be blurred. Depreciated clarity in student leadership and reduced confidence of student leaders due to high conflict and the observed authority dynamics have implications for the role and task of student leadership.

Efforts to reduce anxiety as a consequence of conflict should be a priority. This priority may contribute to sustainable learning environments (Mahlomaholo 2014). Instead of viewing student leadership authority as a threat, it might be worthwhile to consider fostering student leaders' confidence, with aim toward psychological safety and security. Thus focus on the primary task is enabled including achieving functional subgrouping that facilitates working with the diversity and diversity dynamics within the system. Having gained insight on the system psychodynamics of student leadership, it is clear that psychologists have an important contribution to make to ensuring the mental health of student leaders.

REFERENCES

Agazarian, Y. M. 2012a. "Systems-centered Group Psychotherapy: A Theory of Living Human Systems and its Systems-centered Practice." Group 36(1): 19-36. [ Links ]

Agazarian, Y. M. 2012b. "Systems-centered Group Psychotherapy: Putting Theory into Practice." International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 62(2): 171-195. [ Links ]

Akhtar, S. 2018. Mind, Culture, and Global Unrest: Psychoanalytic Reflections. Routledge. [ Links ]

Albertus, R. W. 2019. "Decolonisation of Institutional Structures in South African Universities: A Critical Perspective." Cogent Social Sciences 5(1): 1-14. doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1620403. [ Links ]

Pule, N. 2017. "The Social Construction of Student Leadership in a South African University." PhD dissertation, UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Butler-Adam, J. 2018. "The Fourth Industrial Revolution and Education." South African Journal of Science 114(5-6). https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2018/a0271. [ Links ]

Chamberlain, K., T. Cain, J. Sheridan, and A. Dupuis. 2011. "Pluralisms in Qualitative Research: From Multiple Methods to Integrated Methods." Qualitative Research in Psychology 8(2): 151-169 doi:10.1080/14780887.2011.572730. [ Links ]

Cilliers, F. 2017. "The Systems Psychodynamic Role Identity of Academic Research Supervisors." South African Journal of Higher Education 31(1): 29-49. [ Links ]

Clarke, S. and P. Hoggert. 2009. Researching Beneath the Surface: A Psychosocial Approach to Research Practice and Method. In Researching Beneath The Surface: Psycho-Social Research Methods in Practice, ed. S. Clarke and P. Hoggert, 1-24. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Cross, M. 2004. "Institutionalising Campus Diversity in South African Higher Education: Review of Diversity Scholarship and Diversity Education." Higher Education 47: 387-410. [ Links ]

Cross, M. and C. Carpentier. 2009. "'New Students' in South African Higher Education: Institutional Culture, Student Performance and the Challenge of Democratisation." Perspectives in Education 27(1): 6-18. [ Links ]

Frosh, S. 2019. "Psychosocial Studies with Psychoanalysis." Journal of Psychosocial Studies 12(2): 101-114. https://doi.org/10.1332/147867319X15608718110952-. [ Links ]

Getz, L. M. and M. Roy. 2013. "Student Leadership Perceptions in South Africa and the United States." International Journal of Psychological Studies 5(2): 1-10. doi:10.5539/ijps.v5n2pl. [ Links ]

Griffiths, D. 2019. "#FeesMustFall and the Decolonised University in South Africa: Tensions and Opportunities in a Globalising World." International Journal of Educational Research 94: 143149. https://doi.org/10.1016/jijer.2019.01.004. [ Links ]

Hook, Derek. 2004a. Frantz Fanon, Steve Biko, 'Psychopolitics', and Critical Psychology. London: LSE Research Online. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/961. [ Links ]

Hook, Derek. 2004b. "Fanon and Psychoanalysis of Racism." In Critical Psychology, ed. Derek Hook, 114-137. Lawnsdowne: Juta Academic Publishing. [ Links ]

Jansen, J. D. 2003. "On the State of South African Universities: Guest Editorial." South African Journal of Higher Education 17(3): 9-2. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC37030. [ Links ]

Jansen, Jonathan. 2018. "The Future Prospects of South African Universities." Viewpoints 1(June): 1-13. [ Links ]

Kohut, H. 2004. "Self-psychology and Narcissism." In Object Relations and Self-Psychology: An Introduction, ed. M. St Claire and J. Wigren, 145-168. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. [ Links ]

Koortzen, P. and F. Cilliers. 2005. "Working with Conflict in Teams - The CIBART Model." HR Future 10(1): 52-53. [ Links ]

Lawrence, W. G. (Ed.). 1998. Social Dreaming @ Work. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Long, S. (Ed.). 2013. Socioanalytic Methods: Discovering the Hidden in Organisations and Social Systems. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Luescher-Mamashela, T. M. 2013. "Student Representation in University Decision Making: Good Reasons, a New Lens?" Studies in Higher Education 38(10): 1442-1456. doi:10.1080/03075079.2011.625496. [ Links ]

Lumadi, T. E. and K. C. Mampuru. 2010. "Managing Change in the student Affairs Divisions of Higher Education Institutions." South African Journal of Higher Education 25(5): 716-729. [ Links ]

Mahlomaholo, S. M. G. 2014. "Higher Education and Democracy: Analysing Communicative Action in the Creation of Sustainable Learning Environments." South African Journal of Higher Education 28(3): 678-696. [ Links ]

May, M. S. 2012. "Diversity dynamics Operating Between Students, Lecturers and Management in a Historically Black University: The Lecturers' Perspective." SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 38(2): 138-146. doi:/10.4102/sajip. [ Links ]

Mayer, C. H., L. Tonelli, R. M. Oosthuizen, and D. Surtee. 2018. "'You Have to Keep Your Head on Your Shoulders': A Systems Psychodynamic Perspective on Women Leaders." SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 44(1): 1-15. [ Links ]

Mersky, R. R. 2013. "Social Dream Drawing: Drawing Brings the Inside Out." In Psychosocial Methods: Discovering the Hidden in Organisations and Social Systems, ed. S. Long, 153-178. London: Karnac. [ Links ]

Mersky, R. R. 2015. "How can we Trust our Research and Organisational Praxes? A Proposed Epistemology of Psychosocial Methodologies." Organisational and Social Dynamics 15(2): 279299. [ Links ]

Mersky, R. and B. Sievers. 2019. "Social Photo-Matrix and Social Dream-Drawing." In Methods of Research into the Unconscious: Applying Psychoanalytic Ideas to Social Science, ed. K. Stamenova and R. D. Hinshelwood, 145-168. Routledge. [ Links ]

Mukoza, S. K. and S. Goodman. 2013. "Building Leadership Capacity: An Evaluation of the University of Cape Town's Emerging Student Leaders Programme." Industry and Higher Education 27(2): 129-137. [ Links ]

Niemann, R. 2010. "Transforming an Institutional Culture: An Appreciative Inquiry." South African Journal of Higher Education 24(5): 1003-1022. [ Links ]

Nwoye, A. 2017. "An Africentric theory of human personhood." Psychology in Society 54: 42-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2309-8708/2017/n54a4. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, R. M. and C. H. Mayer. 2019. "At the Edge of the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Employees' Perceptions of Employment Equity from a CIBART Perspective." SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 45(1): 1-11. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa. 1997. Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997). Government Gazette 390 (18515). https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a101-97.pdf. [ Links ]

Singh, R. J. 2015. "Current Trends and Challenges in South African Higher Education: Part 1." South African Journal of Higher Education 29(3): 1-7. [ Links ]

Swartz, R., M. Ivancheva, L. Czerniewicz, and N. P. Morris. 2019. "Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Dilemmas Regarding the Purpose of Public Universities in South Africa." Higher Education 77(4): 567-583. [ Links ]

Xing, B. and T. Marwala. 2017. "Implications of the Fourth Industrial Age for Higher Education." The Thinker 73(3): 10-15. [ Links ]

Valandra, V. 2012. "Reflexivity and Professional Use of Self in Research: A Doctoral Student's Journey." Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research 6(4): 204-220. [ Links ]

Waghid, Y. 2003. "Democracy, Higher Education Transformation and Citizenship in South Africa." South African Journal of Higher Education 17(1): 91-97. [ Links ]

Yang, M., H. Schloemer, Z. Zhu, Y. Lin, W. Chen, and N. Dong. 2020. "Why and When Team Reflexivity Contributes to Team Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model." Frontiers in Psychology 10: 3044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03044. [ Links ]