Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.36 n.1 Stellenbosch Mar. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/36-1-4546

GENERAL ARTICLES

Self-Regulated learning strategies and academic performance of accounting students at a South African university

E. Papageorgiou

School of Accountancy University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9356-6123

ABSTRACT

ORIENTATION: Knowledge of a subject and cognitive strategies are usually not enough to increase students' academic performance; students need also to be motivated to use learning strategies and deal with test and examination anxiety to be successful, especially in their first year of study

PURPOSE: The purpose of the study was to measure first-year accounting students' motivational aspects and learning strategies versus academic performance at a South African university

RESEARCH QUESTIONS: Three research questions were used to determine if students were motivated and applied learning strategies to perform in the accounting course: 1) What motivational variables and learning strategies are related to academic performance measuring students' final Accounting marks, controlling for admission requirements, gender, race, and degree choice? 2) Are prior knowledge demographic and degree choice related to motivational variables and learning strategies? 3) Are motivational variables related to learning strategy variables for Accounting students regarding their Degree choice?

METHOD: A full scale "Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire" (MSLQ) was used to assess accounting students' (N=617) motivational orientations and their use of different learning strategies for an accounting course. Multiple regression analysis was applied to explore the relationship among the different variables

FINDINGS: The findings of this study are relevant to learning in predicting academic performance of first-year accounting students and relationships between self-regulated learning and students' degree choice, gender, race, academic performance and admission requirements. Limitation and further recommendation: This study was only deployed to accounting students at one South African university. A further recommendation would be to collaborate with other disciplines and universities to determine if motivational and learning strategies differ from those of accounting students at a South African university

Value of the study and practical implications: The value of the study provides insights and evidence on motivational beliefs and learning strategies of students in accounting studies and how students can improve their academic performance.

Keywords: academic performance, accounting, Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ), self-regulation, South Africa, students, university

INTRODUCTION

"Any fool can know, the point is to understand" - Albert Einstein, (Einstein n.d.) and in this context, self-regulated learning is an important area of research (Pintrich 1995). The most important aspect of learning is "learning to learn" (Lima Filho and Nova 2019, 236). Knowledge is power, but understanding is everything as students can become better learners if students are more aware of their learning (Chen 2002). Knowledge of the subject and cognitive strategies are usually not enough to increase students' academic performance. Students need also to be motivated to use learning strategies and deal with test and examination anxiety (Pintrich 1995) to be successful, especially in their first year of study. Entry into university can be exciting but also stressful, and perhaps overwhelming for some students to adapt to a new academic environment (Pascarella and Terenzini 1991). Students who fail to "adjust quickly and effectively to university social and academic demands" typically result in poor performance or dropout (Woollacott, Snell, and Laher 2013, 229). Poor learning strategies are among many factors that predicts academic performance that results in the high failure rate of first year students in higher education (Maree and Van Rensburg 2013).

This study investigated the ability of self-learning and motivation as measured by the "Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)" (Pintrich and De Groot 1990) to predict academic performance among first year accounting students at a large university in South Africa. Although the "MSLQ has been used widely in studies in different countries", such as Malaysia (Kosnin 2007; Wee, Azis, and Rasit 2006; Buniamin 2012), Iran (Feiz, Hooman, and Kooshki 2013), the United States of America (Pintrich 1995; Pintrich and Garcia 1993; Hilpert et al. 2013; Chen 2002, 14; Eide, Schwartz, and Winter 2004; Dull, Schleifer, and McMillan 2015), Turkey (Sungur and Tekkaya 2006), Taiwan (Lee 1998), New Zealand (Ram et al. 2019), Spain (Rivero-Menéndez et al. 2018), South Africa (Watson et al. 2004; Kritzinger, Lemmens, and Potgieter 2018), Brazil (Lima Filho and Nova 2019), Belgium (Opdecam et al. 2012), Indonesia (Brataningrum and Saptono 2017) and Japan (Wijaya et al. 2018), little is known about the reliability and ability to predict students' academic performance in South Africa with emphasis on self-regulated learning in accounting studies. Some of the largest courses taught in tertiary education are first year courses and are arguably also some of the most challenging for educators and students.

Given these relationships, and the context in which they play out, this study seeks, therefore, to ask the following research questions to address the purpose of the study to measure first-year accounting students' motivational aspects and learning strategies versus academic performance at a South African university:

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

1) What motivational variables and learning strategies are related to academic performance measuring students' final Accounting marks, controlling for admission requirements, gender, race, and degree choice?

2) Are prior knowledge (admission requirements), demographics (gender, race) and degree choice related to motivational variables and learning strategies?

3) Are motivational variables related to learning strategy variables for Accounting students regarding their Degree choice?

The findings of this study are relevant to learning in predicting academic performance of first-year accounting students and relationships between self-regulated learning and students' degree choice, gender, race, academic performance and admission requirements. The relevant literature and theory are now discussed, followed by the methodology and findings of the study. Thereafter, the study ends with the conclusion, followed by the value, limitations, and future recommendations of the study.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORY

Self-regulated learning (SRL), as defined by Pintrich (1995, 7), involves "three general aspects of academic learning; self-regulation of behaviour, motivation and cognition". The importance of these aspects may contribute to academic achievement in that students can learn how to be self-regulated (Zimmerman 2001). A conscientious approach through hard work and dedication is one of the characteristics first year students can choose to have, improving their adjustment to their new environment and academic performance (Papageorgiou and Callaghan 2018). Given the notion that conscientious students reflect on motivation and self-learning confirm that self-regulated students will be "better students and learn more" (Pintrich 1995, 7) which suggests a positive perspective on student learning and teaching. Self-regulated students learn by monitoring their performance, setting goals and forming expectations regarding their academic frameworks (Zimmerman and Schunk 2001). As educators, we need to engage with students to create enthusiasm (Smith 2001) among students to be self-regulators in their own leaning to know "their worth, their competencies, their ability ... and their responsibilities for generating the will to learn" (McCombs 2001, 108). "Theorists believe that learning is not something that happens to students; it is something that happens by students" (Zimmerman 2001, 33).

With the SRL as a basis, the "MSLQ" was developed by Pintrich et al. (1993) for students/scholars in education (primary, high school and tertiary), "regardless of discipline to examine their motivation for learning and learning strategies" (Soemantri, McColl, and Dodds 2018, 2). The "MSLQ" is a valid and "widely used measure of self-regulated learning" as demonstrated and validated by various studies (Pintrich et al. 1993; Feiz et al. 2013; Hamid and Singaram 2016; Bosch, Boshoff, and Louw 2003; Kosnin 2007; Wee et al. 2006; Rivero-Menéndez et al. 2018; Becker 2013, 443). The instrument is used in various disciplines, such as business information systems (Chen 2002), accounting (Eide et al. 2004; Wee et al. 2006; Dull et al. 2015; Buniamin 2012; Lima Filho and Nova 2019; Opdecam et al. 2012), engineering (Kosnin 2007), introductory geoscience courses (Hilpert et al. 2013), "natural science, humanities, social science, computer science and foreign language" (Pintrich et al. 1993, 805), science and English (Pintrich and De Groot 1990), pharmacy, nursing, medicine, law and accounting (Ram et al. 2019), and medical (Soemantri et al. 2018; Somtsewu 2008; Cook, Thompson, and Thomas 2011) but little or none is known of accounting studies in South Africa to predict students' academic performance using SRL.

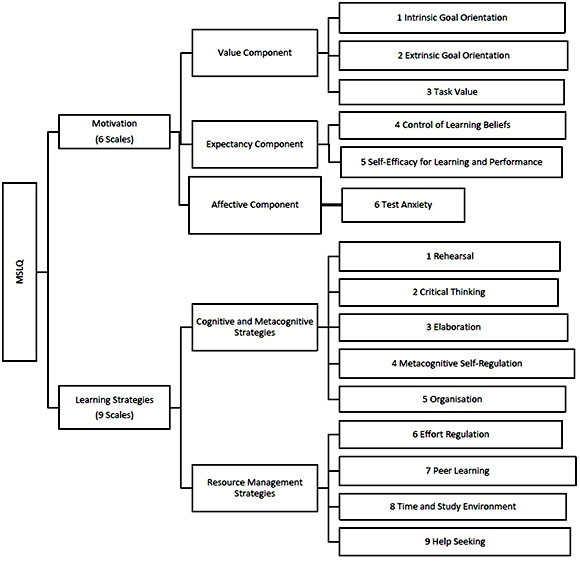

The MSLQ comprises of fifteen subscales divided into two sections; section one; motivation consisting of six subscales with 31 items and section two; learning strategies consisting of nine subscales with 50 items (Pintrich et al. 1993), see Appendix 1. The number of items or subscales used in each of the following studies vary that could have an influence on the results of each study as it also depends on the nature of the study. The "MSLQ consists of 81 items", a full scale (Hilpert et al. 2013; Pintrich et al. 1993; Rivero-Menéndez et al. 2018; Feiz et al. 2013), while Pintrich and De Groot (1990) used 44 items, Buniamin (2012) used 19 items (4 of the 15 scales), Lima Filho and Nova (2019) used 31 items, Dull et al. (2015) used 21 items, Kritzinger et al. (2018) used 50 items (9 of the 15 subscales), Ram et al. (2019) used 31 items, Rivero-Menéndez et al. (Rivero-Menéndez et al. 2018) used 24 items and Brataningrum and Saptono (2017) used 25 learning motivation questions adapted from the MSLQ. Some studies combined the MSLQ with other measures like the Self-regulated Learning Strategies (SRLS) (Lima Filho and Nova 2019, 241) that consists of "fourteen possible strategies for self-regulated learning", the "Academic Self-concept" (ASC) (Ram et al. 2019, 125) questionnaire that is a "measure of student's confidence in their abilities" and the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI) questionnaire to measure students' metacognitive awareness (Cronk 2012).

Prior studies were reviewed that administered the MSLQ in different countries and disciplines and the following empirical studies were selected as this study aims to further examine using one or more of the following criteria: first year students, accounting studies, studies in South Africa and/or studies in higher education. The reasons for these selections are underpinned by the existing literature and the nature of this study since Chen (2002) and Somtsewu (2008) recommended further research to determine the suitability of the MSLQ for various disciplines. Cronk (2012, 114) indicated that "published research in this area in the South African context however appears more limited" as well as Bosch et al. (2003) and Watson et al. (2004) indicated that more studies should be undertaken at various academic institutions.

Firstly, the reasons for this selection of first year students are twofold; some first year courses are service courses for some students which influences the level of motivation of the courses (Kritzinger et al. 2018) and the second reason, the wide range of preparedness of the student upon entry with the majority of students being "underprepared evident of South African's school-leavers" (Scott, Yeld, and Hendry 2007, 37; Kritzinger et al. 2018). The study under review includes two accounting courses which some students use as a service course while most students continue with the professional curriculum as determined by the university and professional bodies. Therefore, the level of motivation could be different as students prepare for class, engage in tasks and respond to assessments and tests (Pintrich 1995). By contrast, Buniamin (2012) used final year Accounting and Business students in their study as these students have been exposed to most core subjects and have experienced a variety of learning environments. Nationally, prior studies (Baard et al. 2010; Papageorgiou and Carpenter 2019; Steenkamp, Baard, and Frick 2009; Fraser and Killen 2003) indicated the significance of studies of first-year students in higher education. These studies respectively indicated that the following factors are good predictions for the success of first year students: prior knowledge of Accounting, lecture attendance, self-motivation, self-discipline, access to resources and locus of control, to name a few.

Secondly, The "South African Institute of Chartered Accountants" (SAICA) accredits programmes offered by universities to train future Chartered Accountants (CAs) (SAICA 2020). These programmes are designed for students to prepare students for the profession in accounting studies that requires not only technical skills, but also to develop life-long learning skills (Becker 2013) to be life-long learners (Smith 2001) and to prepare learners for the workplace.

Thirdly, Students enrolling in South African universities are "from a wide range of social and culture backgrounds" (Fraser and Killen 2003, 254) that is not unique comparing to other countries "shifting from elite to mass education" (Mckenzie and Schweitzer 2001, 21). However, a South African study by Bosch et al. (2003, 39), argued that "overall university research outputs are low, dropout rates high, and graduation numbers poor". South African tertiary institutions that meet graduation and democratic targets will gain financially, "those who do not, will lose out" (Bosch et al. 2003, 39).

Finally, one of the most common factors is prior knowledge in the learning environment (Wahab 2012) and the impact on academic performance (Chen 2002; Papageorgiou and Carpenter 2019). Students entering higher education need to obtain certain entry requirements (Fraser and Killen 2003) set by each university when applying for a degree, for example, admission point scores (APS) (University of the Witwatersrand 2020) or faculty point scores (FPS) (University of the Cape Town 2020) or any other requirement (University of Stellenbosch 2020). These scores/points are calculated from marks obtained in their final exam (Grade 12 or National Senior Certificate (NSC)). For example, a student needs to obtain an APS of 39+ for a Bachelor of Commerce degree and an APS of 42+ for the Chartered Accountant degree to apply for these degrees. Fraser and Killen (2003) confirmed that admission requirements are essential to allow only valid students to their degree choice to be capable of success at university. However, there can be "no guarantee that these students will eventually satisfy the requirements for graduation" (Fraser and Killen 2003, 254). Educators may have limited or no control of the admission process but are responsible to teach these students (Kritzinger et al. 2018). One of the limitations of the study of Pintrich and De Groot (1990) is that student knowledge factors were not assessed and yet correlate to student academic performance that could be a critical factor of students entering higher education.

South African studies

Prior studies which administrated the MSLQ in South Africa were limited; four of the seven studies (Somtsewu 2008; Bosch et al. 2003; Watson et al. 2004; McSorley 2004) were from the same South African university, while the remainder of the studies were from three different South African universities (Hamid and Singaram 2016; Cronk 2012; Kritzinger et al. 2018). The discipline and year of study of the respective seven South African studies differ; two studies conducted research including "first year Psychology students" (Watson et al. 2004; Cronk 2012) while the other five studies including; first year Biology students, focusing on at-risk students (Kritzinger et al. 2018), first year Health Science students (Hamid and Singaram 2016), first, second and third year Business Management students (Bosch et al. 2003), three cultural groups (McSorley 2004) and thirteen Expert Reviewers (Somtsewu 2008). Somtsewu (2008, 56) confirmed that "MSLQ has been extensively researched internationally but fewer studies conducted in South Africa". No Accounting studies were found in South Africa which administrated the MSLQ.

Only three South African studies which administered the MSLQ (Hamid and Singaram 2016; Cronk 2012; Watson et al. 2004), each from a different South African university, were further examined to test the validity of the MSLQ that include first year students in respect of the discipline of the study. The study by Kritzinger et al. (2018) also focused on first year students; however, this group focused on at-risk students. According to the study by Somtsewu (2008, 29) "due to the lack of factorial invariance, limited support was therefore found for the construct validity of the MSLQ in a South African context".

In the first South African study, Hamid and Singaram (2016, 104) investigated "motivated strategies for learning ... versus academic performance of a diverse group" of 165 first year "Medical students". The "MSLQ" was administrated using a full scale, 81 items, and according to Hamid and Singaram (2016) limited research was done in the health professions education. "Significant but moderate relationships were found between academic performance and the motivation strategies subsumed within the categories 'task value' and 'self-efficacy for learning performance'" (Hamid and Singaram 2016, 104). Hamid and Singaram (2016, 106) confirmed that the "'learning strategy component', 'critical thinking', and 'time and study environment', the composite score was significantly but poorly correlated to academic performance". In addition, students' prior educational experience and attendance of peer-monitoring sessions had significantly higher learning strategy scores in relation to the other learning strategies. The results further indicated that females demonstrated significantly higher motivational scores than males (Hamid and Singaram 2016).

In the second South African study, Cronk (2012) examined the extent of the associations between motivation, metacognition and performance of268 first-year Psychology students. The MSLQ, consisting of 81 items, was combined with the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI) questionnaire to measure students' metacognitive awareness. Cronk (2012) concluded that the "MSLQ Motivation subscale" indicated no substantial relationships with academic performance. Cronk (2012, 115) indicated a "high degree of inter-correlation amongst the variables of metacognition and motivation, suggesting tremendous overlap, and difficulties in assessing such constructs independently from one another". In addition, Cronk (2012,115) concluded that "virtually none of the key variables were found to be significant predictors of academic performance".

In the third South African study, Watson et al. (2004) investigated 81 first year Psychology students exploring their motivation and learning strategies. The participants surveyed the "MSLQ" consisting of 81 items. Watson et al. (2004, 204) confirmed that "nine of the fifteen Motivation and Learning Strategy subscales were significantly related to the academic performance". Another finding of Watson et al. (2004, 205) indicated that "lower achieving learners reported less use of learning strategies and motivation". Watson et al. (2004) suggested that educators should include interventions to eliminate or reduce the number of lower achieving learners to improve their academic performance (Somtsewu 2008). Watson et al. (2004, 200) confirmed first-year students "who planned their studying, monitored ongoing results", arranged their study time and customary place of study perform better academically than those who did not. The limitations of the study are that a small sample size was used and advanced correlation and regression analyses should be performed with larger samples (Watson et al. 2004).

International studies

Literature was reviewed of international studies who administrated the MSLQ of students in Accounting studies at all year levels. Lima Filho and Nova (2019, 236) evaluated the "self-regulated and self-determination theory of Accounting graduate students in Brazil". The study focussed on 516 graduate Accounting students, at Master and Doctoral level, and confirmed that these students have mature and confident profiles. Brataningrum and Saptono (2017) investigated the impact and effectiveness of 238 high school students' learning achievements in Indonesia. Brataningrum and Saptono (2017) concluded that the learning process has a positive impact on learning motivation, self-efficacy and learning achievements. Students' effectiveness are present if they are actively involved in the learning process since educators are setting goals and developing learning plans where educators are the drivers and the students the "doers" (Brataningrum and Saptono 2017). Ram et al. (2019) investigated 34 third year accounting students that forms part of 363 students of other disciplines in New Zealand on "Cognitive Enhancers and Learning Strategies". Ram et al. (2019, 127) concluded that "Accounting students had the lowest student self-concept, task value and self-efficacy for learning" comparing to 47 nursing students who had the highest score. Other disciplines were law, medicine and pharmacy. Wee et al. (2006) conducted a research in distributing the full scale MSLQ to 600 accounting students in the Faculty of Accountancy in Malaysia to determine students' motivated behaviour towards their studies. The results of the study by Wee et al. (2006) indicated that self-regulated learning is motivated by self-efficacy and task value. Eide et al. (2004) also surveyed the full scale MSLQ of 162 students of two upper level Accounting courses to establish students' learning strategies at an American university. Eide et al. (2004, 60) suggested that there is "a potential benefit from learning strategy instruction if presented earlier in the students' college career". In the study by Buniamin (2012), only four of the fifteen subscales of the MSLQ were surveyed of 98 final year Accounting and Business students in Malaysia which aimed to develop a good learning strategy to influence academic success. Buniamin (2012, 37) concluded that "no significant differences were found in all self-regulated learning strategies ... for both the Accounting and Business students".

Only three studies which administered the MSLQ focused on Accounting studies of first year students in higher education. Dull et al. (2015, 152) investigated the "relationship of Accounting students' goal orientations with self-efficacy, anxiety and achievement" of 521 students of an "Introductory Financial Accounting Course" in an American university. Only 21 of the 81 items of the MSLQ were administered. The results of the study demonstrated that a combination of mastery and performance goal motivation may provide better results associated with academic achievement rather that single goals that may assist educators to influence student success. In the second study, Opdecam et al. (2012, 1) administrated the full scale of the MSLQ to 291 accounting students in their first year of study at a large university in Belgium to determine "the effect of team learning on student profile and student performance". The study investigated student' preferences for learning, team- or lecture-based learning, in the relation to learning strategy, motivation, gender and ability (Opdecam et al. 2012). Opdecam et al. (2012) concluded team-learning students were more motivated, resulted in increased performance, had a lower ability level and had less control of their beliefs than lecture-learning students. Females preferred team-learning (Opdecam et al. 2012). In the third and final study, Becker (2013) evaluated "Self-Regulated Learning Interventions" of 244 students enrolled for the "Introductory Accounting Course" at an American university. Learners in their first year of study often struggle with self-monitoring in attempting academic tasks regarding the complexity of course material and self-reflection on concepts learnt (Becker 2013). The MSLQ was administered using 51 items; Becker (2013) concluded that the study was the first study of self-regulated learning interventions designed for an Accounting Course. The results of the study by Becker (2013) confirmed that the interventions may improve academic achievement on forthcoming academic tasks.

The literature reviewed in this study indicates substantial progress during the past fifteen years investigating motivation and self-regulated learning of tertiary students in South Africa.

METHOD

The research method was quantitative, employing an on-line electronic questionnaire (Bryman and Bell 2012) to collect data which was used to test the research questions.

Participants

The sampling frame includes first-year accounting students (N=777) registered for the following two accounting courses; the Financial Accounting (N=402) course that forms part of the "Bachelor of Commerce Degree in Accounting Science" (B.AccSc) in becoming a Chartered Accountant (CA) and the Accounting (N=375) course that forms part of the "General Bachelor of Commerce Degree" (B.Com) at a large university in South Africa. The students under review were characterised by large classes, range of prior knowledge and diverse backgrounds (Fraser and Killen 2003; Papageorgiou and Carpenter 2019; Papageorgiou 2017).

Data collection

Data was collected using an on-line electronic questionnaire about two weeks before the final examination period (Wee et al. 2006), at the end of the academic year (Rivero-Menéndez et al. 2018; Hilpert et al. 2013). Two sets of data were collected: firstly, student biographical data (degree choice, gender, race, accounting degree, academic performance and admission point score (APS)). The academic performance indicates students' final marks (expressed as a percentage out of 100%) obtained from the two accounting courses. Secondly, data was collected from the "Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)" consisting of 81 items and is "based on a general cognitive view of motivation and learning strategies" (Pintrich et al. 1991, 3).

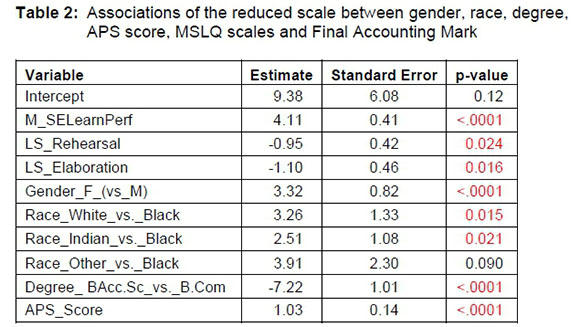

Sample size

Sample size estimation was based on the key research question, in this case the association between gender, race, degree, APS score, MSLQ scales and final Accounting examination mark. Multiple regression analysis requires 15-20 observations (students) per parameter to be estimated. In this case, 22 parameters to be estimated, thus requiring a sample size of 330-440. The actual sample size of 617 meets these requirements.

Research instrument

The "MSLQ" was "developed formally in 1986 by the National Center for Research to Improve Postsecondary Teaching and Learning (NCRIPTAL)" (Pintrich et al. 1991, 3) and administered to accounting students to measure students' "motivational orientations and their use of different learning strategies" (Pintrich et al. 1991; Chen 2002; Pintrich and Garcia 1993). This MSLQ

comprises two sections "Motivation" and "Learning Strategies", see Appendix 1. A "7-point Likert Scale", ranging from "very true of you" and "not at all true of you" was used in terms of students' behaviour in accounting lectures. The two extremes, if the statement is true, students had the option to select one and if the statement is untrue, students had the option to select seven and any value between one and seven that best describes each option. Within the application cluster of items, the following specific amendments were made; "instructor" was replaced by "lecturer" and the term "class" was replaced with "lecture", more commonly used terms in the South African higher education context.

Procedure

Accounting students received an invitation via the university portal to take part in the study and the link was made available on the portal. The lecturer briefed the aim and contribution of the research. Students provided their student number to link the questionnaire results to academic marks and the data was reported anonymously as a group level and not individually. Approval for ethics clearance was obtained from the university under review, protocol number H19/08/34. Data analysis was carried out using "SAS version 9.4 for Windows". A 5 per cent significance level was used to describe the sample and was used to analyse the data. The reliability of each MSLQ scale was determined by Cronbach alpha (Hair et al. 2013). The values of Cronbach alpha were comparable to those given in the MSLQ manual (Pintrich et al. 1991). The results are now discussed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The response rate was 651/777=83.8 per cent, 34 respondents were excluded due to missing data, leaving 617 for the analysis. MSLQ scales were scored if responses were present for at least 75 per cent of the items. Of the 617 students, 56.1 per cent were female, race was categorised as follows: 69.7 per cent Black, 17.0 per cent Indian, 10.2 per cent White and 3.1 per cent other race group. Regarding the two main degree groups; 55.1 per cent (N=340) of the students enrolled for the "Bachelor of Commerce Science Degree (BAccSci)" and 44.9 per cent (N=277) of the students enrolled for the "Bachelor of Commerce (BCom)" degree. The respondents obtained a Final Mark of 60.5 per cent and the mean for the APS score was 43.7. Extrinsic Goal Orientation subscale was the highest (6.0; IQR 5.3-6.5) while that of the Peer learning subscale was the lowest (4.0; IQR 2.7-5.0). The four questions relating to "Extrinsic Goal Orientation scale" were: "Getting a good grade", "Improving my overall grade", "to get better grades in this class than most of the other students" and "to do well in this class because it is important to show my ability to my family, friends, employer, or others".

The analysis initially addressed the first research question, "What motivational variables (measuring the "value, expectancy and affective components" (Pintrich et al. 1991, 1)) and learning strategies ("measuring cognitive, metacognitive and resource management strategies" (Pintrich et al. 1991, 1)) are related to academic performance measuring students' final Accounting marks, controlling for admission requirements, gender, race, and degree choice?" The relationship was assessed using multiple regression with the score as the dependent variable, and gender, race, degree, APS score and all MSLQ scale scores as the independent variables. Following the methodology used by Chen (2002), variables with a beta parameter of <0.1 were then excluded from the final model, while retaining all significant variables.

The model indicated an adjusted R2 of 0.30 (F(21,595) = 13.3; p<0.0001) for all the variables. "Self-Efficacy (SE) for Learning and Performance" was positively associated with higher Final Marks, while "Rehearsal" involving memorising and reciting (Pintrich et al. 1991, 18) and "Elaboration" indicating summarising, and using examples (Pintrich et al. 1991, 19) were negatively associated with higher Final Marks. The "SE for Learning and Performance" related to expectancy for success; believe in receiving excellent marks, be confident and master skills taught in class (Pintrich et al. 1991, 14). The findings of this study also confirmed the studies of Hamid and Singaram (2016), Watson et al. (2004) and Dull et al. (2015) that students who believed they would do well are more likely to obtain higher marks while Cronk (2012) indicated no substantial relationships were found regarding the "Motivation subscale". Among the demographic variables; females, Indian, White and B.Com students and a higher APS score were significantly associated with higher Final Marks. No other variables had a beta coefficient >0.1 so only these significant variables were retained for the reduced, final, model. The final model had an adjusted R2 of 0.27 (F(9,607) = 25.8; p<0.0001). The findings are indicated in Table 2.

The second research question addressed "Was prior knowledge (referring to APS), demographic (gender, race) and degree choice related to motivational variables and learning strategies?" The association between each MSLQ subscale score and gender, race, degree and APS score, was assessed using a General Linear Model (GLM) with the score as the dependent variable, and gender, race, degree and APS score as the independent variables. Outliers were removed as indicated by model diagnostics. Post hoc tests were conducted using the "Tukey-Kramer" adjustment for multiple comparisons (Hair et al. 2013).

The results are summarised per Table 3. There was a significant effect of Gender for eight scales. Females (compared to males) scored lower on the "Intrinsic Goal Orientation", "SE for Learning and Performance" and "Critical Thinking" subscales, and higher on the "Test Anxiety, Rehearsal, Organisation, Time & Study Environment and Effort Regulation" subscales. Similar to the study of Dull et al. (2015), a lower score was found for females for Self-efficacy and a higher score for Test Anxiety. It was found that female students managed their time more effectively, are more committed and organised than male students while male students are more task and performance orientated. In contrast, in the study by Hamid and Singaram (2016), female students scored higher on motivation than males. There was a significant effect of Race for three scales. White and Indian students (compared to Black students) scored lower on the "Extrinsic Goal Orientation and Task Value subscales". Indian students (compared to Black students) scored lower on the "SE for Learning and Performance subscale". There was a significant effect of Degree Choice for nine scales. B.AccSc students (compared to B.Com students) obtained a lower score on the "SE for Learning and Performance subscale", and higher on the "Extrinsic Goal Orientation, Task Value, Test Anxiety, Rehearsal, Elaboration, Organisation, Critical Thinking and Time & Study Environment" subscales. B.AccSc students obtained a lower score than B.Com students in expectancy for success and self-efficacy but these students were committed to getting good marks, organising information and manage study time that should result in better performance. There was a significant effect of APS score for two scales. A higher APS score was associated with a higher score for "SE for Learning and Performance", and a lower score for "Test Anxiety". For continuous variables (APS score): A 1-point increase in APS score corresponded with an average 0.05 point increase in the "SE for Learning and Performance and Task Value" subscales, relating to students' self-efficacy and success to performance are expected to be more successful than students with a lower APS score.

And finally, the third research question, "Are motivational variables related to learning strategy variables for Accounting students regarding their Degree choice?" First order correlations between MSLQ subscales were determined by Spearman's correlation coefficient. The results are illustrated in Tables 3 and 4. For the groups, B.AccSc and B.Com, almost all scales were significantly positively correlated. For both groups, the strongest correlations (r>0.6) were between: firstly, "Intrinsic Goal Orientation and Task Value, Self-Efficacy for Learning; and Performance"; and secondly, "Effort Regulation and Time & Study Environment". The students of these groups are goal orientated relating to the evaluation of tasks in respect of how interesting, important and useful tasks are in obtaining good marks. In addition, these students use their time effectively in summarising their work and making use of examples. For the B.AccSc group, strong correlations (r>0.6) were between: "Elaboration and Task Value, Rehearsal, Organisation, Critical Thinking, Metacognitive Self-Regulation"; and "Metacognitive Self-Regulation and Rehearsal, Organisation, Critical Thinking". Similarly, the B.Com group indicated strong correlations (r>0.6) between: "Extrinsic Goal Orientation and Task Value"; "Task Value and Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance"; "Organisation and Rehearsal, Elaboration, Metacognitive Self-Regulation"; and "Metacognitive Self- Regulation and Elaboration, Time & Study Environment". The main finding between the two groups was that B.AccSc degree group indicated a correlation between the Critical Thinking subscale relating to "the degree to which students report applying previous knowledge to new situations in order to solve problems, reach decisions, or make critical evaluations with respect to standards of excellence" (Pintrich et al. 1991, 22) and the "Metacognitive Self-Regulation" subscale involving "the awareness, knowledge and control of cognition" (Pintrich et al. 1991, 23) that was not evident in the B.Com group. However, the B.Com group confirmed that higher Extrinsic Goal Orientation results in higher task value of students' perceptions of the course material.

CONCLUSION

The study's research questions were addressed by investigating the ability of self-learning and motivation as measured by the "Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)" (Pintrich and De Groot 1990) to predict academic performance among first year accounting students at a large university in South Africa. The study found significant correlations between the MSLQ self-reported scores and academic performance, admission requirements, gender, race and degree choice. The "Extrinsic Goal Orientation" subscale scored the highest of the fifteen subscales followed by the "Task Value" subscale and thereafter "Control of Learning Beliefs" subscale. Students are firstly, extrinsic orientated to why they participate in tasks secondly, value the importance of tasks and lastly, believe in their efforts to learn, resulting in positive outcomes. Findings of the first research question indicated that the "SE for Learning and Performance" subscale, students who are female, Indian, White, enrolled for a B.Com degree and obtained a higher APS score were significantly associated with higher Final Marks. The second research question concluded that females (compared to males) scored lower on the "Intrinsic Goal Orientation, SE for Learning and Performance and Critical Thinking" subscales, and higher on the "Test Anxiety, Rehearsal, Organisation, Time & Study Environment and Effort Regulation" subscales. A 1-point increase in APS score corresponded with an average 0.05 point increase in the SE for Learning and Performance and Task Value subscales to be more successful than students with a lower APS score. And lastly, the third research question confirmed that Degree choice indicated that BAccSc students applied their previous knowledge in relation to their awareness, knowledge and control of cognition that was not evident in the B.Com group. However, the B.Com group confirmed that higher Extrinsic Goal Orientation results in higher task value of students' perceptions of the course material.

The beneficial value and impact of this study demonstrate that accounting students are consistent with the fact that "Self-efficacy for learning and performance" is recognised by students to succeed and their ability to accomplish tasks as well as confidence in their skills to perform tasks. Lecturers can therefore adapt their lectures to encourage learning in engaging with students in improving students' confidence, resulting in motivating, and embedding learning strategies to improve students' academic performance. While students can use this opportunity to engage in lecturers to learn "how to learn". This research was important to assist lecturers and students with the understanding of the process of learning accounting and creating an environment in which "Self-regulated learning" can be used to increases students' academic performance. In addition, "Self-regulated learning" may assist students to understand their goals and to be responsible of their own beliefs since students need to establish their goals early in their educational process to influence their learning patterns in promoting possibilities for the growth and development of all students. This study also suggests that accounting students need to improve on basic rehearsal strategies and to store information into long-term memory by building connections between accounting concepts learnt. This study is a first for Accounting studies in South Africa and could assist future studies in self-regulated learning strategies and students' academic performance.

The limitation of the study is that it was restricted to only accounting students in their first year of study at a single South African university. There are multiple factors predicting first year students' academic achievement; thus this study focused on self-regulated learning that may shift students' unrealistic expectations about non-academic factors that could reduce students' academic performance.

Future recommendations would be to exposed students to more than one year and also explore other disciplines and universities.

REFERENCES

Baard, R. S., L. P. Steenkamp, B. L. Frick, and M. Kidd. 2010. "Factors Influencing Success in First-Year Accounting at a South African University: The Profile of a Successful First-Year Accounting Student." South African Journal of Accounting Research 24(1): 128-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/10291954.2010.11435150. [ Links ]

Becker, L. L. 2013. "Self-Regulated Learning Interventions in the Introductory Accounting Course: An Empirical Study." Issues in Accounting Education 28(3): 435-60. https://doi.org/10.2308/iace-50444. [ Links ]

Bosch, J., C. Boshoff, and L. Louw. 2003. "Empirical Perspectives on the Motivational and Learning Strategies of Undergraduate Students in Business Management: An Exploratory Study." Management Dynamics 12(4): 39-50. [ Links ]

Brataningrum, P. and L. N. Saptono. 2017. "The Influence of the Effectiveness of Accounting Learning Process on Student Learning Achievements." Journal of Education 36(3): 342-356. [ Links ]

Bryman, A. and E. Bell. 2012. Business Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [ Links ]

Buniamin, S. 2012. "A Comparative Study on Self-Regulated Learning Strategy between Accounting and Business Students." Journal PendidikanMalaysia 37(1): 37-45. [ Links ]

Chen, C. 2002. "Self-Regulated Learning Strategies and Achievement in an Introduction to Information Systems Course." Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal 20(1): 11-23. [ Links ]

Cook, D., W. Thompson, and K. Thomas. 2011. "The Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire: Score Validity among Medicine Residents." Medical Education 45(12): 1230-1240. [ Links ]

Cronk, C. 2012. "Motivation, Metacognition and Performance." Master Dissertation. University of the Witwatersrand. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Dull, R. B., L. L. F. Schleifer, and J. J. McMillan. 2015. "Achievement Goal Theory: The Relationship of Accounting Students' Goal Orientations with Self-Efficacy, Anxiety, and Achievement." Accounting Education 24(2): 152-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09639284.2015.1036892. [ Links ]

Eide, B. J., B. N. Schwartz, and K. Winter. 2004. "Introducing and Reinforcing Learning Strategies with Accounting Students." Journal of Accounting & Finance Research 12(3): 60-69. [ Links ]

Einstein, A. n.d. "Quotes." https://www.quotes.net/authors/Albert+Einstein. (Accessed 25 January 2021). [ Links ]

Feiz, P., H. A. Hooman, and S. H. Kooshki. 2013. "Assessing the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) in Iranian Students: Construct Validity and Reliability." Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 84(4): 1820-1825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.041. [ Links ]

Fraser, W. J. and R. Killen. 2003. "Factors Influencing Academic Success or Failure of First-Year and Senior University Students: Do Education Students and Lecturers Perceive Things Differently?" 23(4): 254-260. [ Links ]

Hair, J. F., W. C. Black, B. J. Babin, and R. E. Anderson. 2013. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th Edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education Limited. [ Links ]

Hamid, S. and V. S. Singaram. 2016. "Motivated Strategies for Learning and Their Association with Academic Performance of a Diverse Group of 1st-Year Medical Students." African Journal of Health Professions Education 8(1): 104-107. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2016.v8i1.757. [ Links ]

Hilpert, J. C., J. Stempien, K. J. Van Der Hoeven Kraft, and J. Husman. 2013. "Evidence for the Latent Factor Structure of the MSLQ: A New Conceptualization of an Established Questionnaire." SAGE Open 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013510305. [ Links ]

Kosnin, A. M. 2007. "Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement in Malaysian Undergraduates." International Education Journal 8(1): 221-228. [ Links ]

Kritzinger, A., J. Lemmens, and M. Potgieter. 2018. "Learning Strategies for First-Year Biology: Toward Moving the 'Murky Middle'." Life Science Education 17(3 ar 42): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-10-0211. [ Links ]

Lee, L. H. 1998. "Goal Orientation, Goal Setting, and Academic Performance in College Students: An Integrated Model of Achievement Motivation in School Settings." Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 59(6): 1905. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=1998-95023-027&site=ehost-live. [ Links ]

Lima Filho, R. N. and S. P. C. C. Nova. 2019. "Self-Regulated Learning and Self-Determination Theory in Accounting Graduate Students in Brazil." European Journal of Scientific Research 152: 236-55. [ Links ]

Maree, C. and G. H. Van Rensburg. 2013. "Reflective Learning in Higher Education: Application to Clinical Nursing." African Journalfor Physical Activity and Health Sciences 1 Supplement 1: 44-55. [ Links ]

McCombs, B. L. 2001. "Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: A Phenomenological View." In Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement, edited by B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk, 67-123. 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mckenzie, K. and R. Schweitzer. 2001. "Who Succeeds at University? Factors Predicting Academic Performance in First Year Australian University Students." Higher Education Research and Development 20(1): 21-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07924360120043621. [ Links ]

McSorley, M. E. 2004. "The Construct Equivalence of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)." Master Dissertation. Port Elizabeth: University of Port Elizabeth. [ Links ]

Opdecam, E., P. Everaert, H. Van Keer, and F. Buysschaert. 2012. The Effect of Team Learning on Student Profile and Student Performance in Accounting Education. University of Gent. [ Links ]

Papageorgiou, E. 2017. "Accounting Students' Profile versus Academic Performance: A Five-Year Analysis." South African Journal of Higher Education 31(3): 209-229. https://doi.org/10.20853/31-3-1064. [ Links ]

Papageorgiou, E. and C. W. Callaghan. 2018. "Personality and Adjustment in South African Higher Education Accounting Studies." South African Journal of Accounting Research 32(2-3): 189-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/10291954.2018.1442649. [ Links ]

Papageorgiou, E. and R. Carpenter. 2019. "Prior Accounting Knowledge of First-Year Students at Two South African Universities: Contributing Factor to Academic Performance or Not?" South African Journal of Higher Education 33(6): 249-264. https://doi.org/10.20853/33-6-3032. [ Links ]

Pascarella, E. T. and P. T. Terenzini. 1991. How College Affects Students. San Francisco, CA.: Jossey Bass. [ Links ]

Pintrich, P. R. 1995. "Understanding Self-Regulated Learning." New Directions for Teaching and Learning 63(Fall): 3-12. [ Links ]

Pintrich, P. R. and T. Garcia. 1993. "Intra-individual Differences in Students' Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning." German Journal of Educational Psychology 7(2): 99-107. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232445042_Intraindividual_differences _in_students'_motivation_and_self-regulated_learning. [ Links ]

Pintrich, P. R. and E. V. De Groot. 1990. "Motivational and Self-Regulated Learning Components of Classroom Academic Performance." Journal of Educational Psychology 82(1): 33-40. http://www.indiana.edu/~p540alex/MSLQ.pdf. [ Links ]

Pintrich, P. R., D. A. F. Smith, T. Garcia, and W. J. McKeachie. 1991. A Manual for the Use of The Motivated Strategies of Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Washington DC. [ Links ]

Pintrich, P. R., D. A. F. Smith, T. Garcia, and W. J. McKeachie. 1993. "Reliability and Predictive Validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)." Educational and Psychological Measurement 53: 801-813. [ Links ]

Ram, S., S. Hussainy, M. Henning, M. Jensen, K. Stewart, and B. Russell. 2019. "Cognitive Enhancers (CE) and Learning Strategies." Journal of Cognitive Enhancement 3(1): 124-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-018-0089-9. [ Links ]

Rivero-Menéndez, M. J., E. Urquía-Grande, P. López-Sánchez, and M. M. Camacho-Minano. 2018. "Motivation and Learning Strategies in Accounting: Are There Differences in English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) versus Non-EMI Students?" Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Accounting Review 21(2): 128-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsar.2017.04.002. [ Links ]

SAICA. 2020. "SAICA, South African Institute for Chartered Accountant: Guidance for Professional Programmes." https://www.saica.co.za/Portals/0/documents/Detailed Guidance to the Competency Framework APC 2020.pdf. [ Links ]

Scott, I., N. Yeld, and J. Hendry. 2007. Higher Education Monitor: A Case for Improving Teaching and Learning in South African Higher Education. Cape Town. The Council of Higher Education. [ Links ]

Smith, P. A. 2001. "Understanding Self-Regulated Learning and Its Implications for Accounting Educators and Researchers." Issues in Accounting Education 16(4): 1-26. [ Links ]

Soemantri, D., G. McColl, and A. Dodds. 2018. "Measuring Medical Students' Reflection on Their Learning: Modification and Validation of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)." BMC Medical Education 18(1): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1384-y. [ Links ]

Somtsewu, N. 2008. "The Applicability of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) for South Africa." Master Dissertation. Port Elizabeth: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. [ Links ]

Steenkamp, L. P., R. S. Baard, and B. L. Frick. 2009. "Factors Influencing Success in First-Year Accounting at a South African University: A Comparison between Lecturers' Assumptions and Students' Perceptions." South African Journal of Accounting Research 3(1): 113-140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10291954.2009.11435142. [ Links ]

Sungur, S. and C. Tekkaya. 2006. "Effects of Problem-Based Learning and Traditional Instruction on Self-Regulated Learning." Journal of Educational Research 99(5): 307-320. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.5.307-320. [ Links ]

University of Cape Town. 2020. "Faculty of Commerce: Admission Requirements." University of Cape Town. http://www.commerce.uct.ac.za/Pages/Admission-Requirements. [ Links ]

University of Stellenbosch. 2020. "Undergraduate Admission Requirements." University of Stellenbosch. http://www.maties.com/assets/File/Elektronies_boekie_Eng_print2.pdf. [ Links ]

University of the Witwatersrand. 2020. "Faculty of Commerce, Law and Management: Admission Requirements." University of the Witwatersrand. http://www.wits.ac.za/prospective/undergraduate/admissionrequirements/ 11644/admission_requirements_nsc.html. [ Links ]

Wahab, M. 2012. "Study on the Impact of Motivation, Self-Efficiency and Learning Strategies of Faculty of Education Undergraduates Studying ICT Course." International Journal of Behavioral Science 2(1): 153-187. [ Links ]

Watson, M., M. McSorley, C. Foxcroft, and A. Watson. 2004. "Exploring the Motivation Orientation and Learning Strategies of First Year University Learners." Tertiary Education and Management 10(3): 193-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2004.9967127. [ Links ]

Wee, S. H., M. A. A. Azis, and Z. A. Rasit. 2006. "Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ): An Empirical Analysis of the Value and Expectancy Theory." Social and Management Research Journal 3(1): 47-65. [ Links ]

Wijaya, H., H. Qudsyi, F. E. Nurtjahjo, and M. A. Rachmawati. 2018. Understanding Academic Performance from the Role of Self-Control and Learning Strategies, 252-261. ICEL Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan. [ Links ]

Woollacott, L., D. Snell, and S. Laher. 2013. "Transitional Distance: A New Perspective for Conceptualizing Student Difficulties in the Transition from Secondary to Tertiary Education." Proceedings of the 2nd Biennial Conference of the South African Society for Engineering Education. [ Links ]

Zimmerman, B. J. 2001. "Theories of Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: An Overview and Analysis." In Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement, edited by B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk, 1-38. 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Zimmerman, B. J. and D.H. Schunk. 2001. "Reflections on Theories of Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement." In Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement, edited by B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk, 289-307. 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Appendix 1: Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)

Motivation (6 Scales)

1. Value Component: Intrinsic Goal Orientation

1. In a lecture like this, I prefer course material that really challenges me so I can learn new things.

16. In a lecture like this, I prefer course material that arouses my curiosity, even if it is difficult to learn.

22. The most satisfying thing for me in this course is trying to understand the content as thoroughly as possible.

24. When I have the opportunity in this lecture, I choose course assignments that I can learn from even if they don't guarantee a good grade.

2. Value Component: Extrinsic Goal Orientation

7. Getting a good grade in this lecture is the most satisfying thing for me right now.

11. The most important thing for me right now is improving my overall grade point average, so my main concern in this lecture is getting a good grade.

13. If I can, I want to get better grades in this lecture than most of the other students.

30. I want to do well in this lecture because it is important to show my ability to my family, friends, employer, or others.

3. Value Component: Task Value

4. I think I will be able to use what I learn in this course in other courses.

10. It is important for me to learn the course material in this lecture.

17. I am very interested in the content area of this course.

23. I think the course material in this lecture is useful for me to learn.

26. I like the subject matter of this course.

27. Understanding the subject matter of this course is very important to me.

4. Expectancy Component: Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance

5. I believe I will receive an excellent grade in this lecture.

6. I'm certain I can understand the most difficult material presented in the readings for this course.

12. I'm confident I can understand the basic concepts taught in this course.

15. I'm confident I can understand the most complex material presented by the lecturer in this course.

20. I'm confident I can do an excellent job on the assignments and tests in this course.

21. I expect to do well in this lecture.

29. I'm certain I can master the skills being taught in this lecture.

31. Considering the difficulty of this course, the teacher, and my skills, I think I will do well in this lecture.

5. Expectancy Component: Control of Learning Beliefs

2. If I study in appropriate ways, then I will be able to learn the material in this course.

9. It is my own fault if I don't learn the material in this course.

18. If I try hard enough, then I will understand the course material.

25. If I don't understand the course material, it is because I didn't try hard enough.

6. Affective Component: Test Anxiety

3. When I take a test I think about how poorly I am doing compared with other students.

8. When I take a test I think about items on other parts of the test I can't answer.

14. When I take tests I think of the consequences of failing.

19. I have an uneasy, upset feeling when I take an exam.

28. I feel my heart beating fast when I take an exam.

Learning Strategies (9 Scales)

1. Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Rehearsal

39. When I study for this lecture, I practice saying the material to myself over and over.

46. When studying for this lecture, I read my lecture notes and the course readings over and over again.

59. I memorize key words to remind me of important concepts in this lecture. 72. I make lists of important terms for this course and memorize the lists.

2. Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Critical Thinking

38. I often find myself questioning things I hear or read in this course to decide if I find them convincing.

47. When a theory, interpretation, or conclusion is presented in lecture or in the readings, I try to decide if there is good supporting evidence.

51. I treat the course material as a starting point and try to develop my own ideas about it.

66. I try to play around with ideas of my own related to what I am learning in this course.

71. Whenever I read or hear an assertion or conclusion in this lecture, I think about possible alternatives.

3. Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Elaboration

53. When I study for this lecture, I pull together information from different sources, such as lectures, readings, and discussions.

62. I try to relate ideas in this subject to those in other courses whenever possible.

64. When reading for this lecture, I try to relate the material to what I already know.

67. When I study for this course, I write brief summaries of the main ideas from the readings and the concepts from the lectures.

69. I try to understand the material in this lecture by making connections between the readings and the concepts from the lectures.

81. I try to apply ideas from course readings in other lecture activities such as lecture and discussion.

4. Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Metacognitive Self-Regulation

33. During lecture time I often miss important points because I'm thinking of other things.

36. When reading for this course, I make up questions to help focus my reading.

41. When I become confused about something I'm reading for this lecture, I go back and try to figure it out.

44. If course materials are difficult to understand, I change the way I read the material.

54. Before I study new course material thoroughly, I often skim it to see how it is organized.

55. I ask myself questions to make sure I understand the material I have been studying in this lecture.

56. I try to change the way I study in order to fit the course requirements and lecturer's teaching style.

57. I often find that I have been reading for lecture but don't know what it was all about.

61. I try to think through a topic and decide what I am supposed to learn from it rather than just reading it over when studying.

76. When studying for this course I try to determine which concepts I don't understand well.

78. When I study for this lecture, I set goals for myself in order to direct my activities in each study period.

79. If I get confused taking notes in lecture, I make sure I sort it out afterwards.

5. Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Organization

32. When I study the readings for this course, I outline the material to help me organize my thoughts.

42. When I study for this course, I go through the readings and my lecture notes and try to find the most important ideas.

49. I make simple charts, diagrams, or tables to help me organize course material.

63. When I study for this course, I go over my lecture notes and make an outline of important concepts.

6. Resource Management Strategies: Effort Regulation

37. I often feel so lazy or bored when I study for this lecture that I quit before I finish what I planned to do.

48. I work hard to do well in this lecture even if I don't like what we are doing. 60. When course work is difficult, I give up or only study the easy parts.

74. Even when course materials are dull and uninteresting, I manage to keep working until I finish.

7. Resource Management: Peer Learning

34. When studying for this course, I often try to explain the material to a class mate or a friend.

45. I try to work with other students from this lecture to complete the course assignments.

50. When studying for this course, I often set aside time to discuss the course material with a group of students from the lecture.

8. Resource Management Strategies: Time and Study Environment

35. I usually study in a place where I can concentrate on my course work.

43. I make good use of my study time for this course. 52. I find it hard to stick to a study schedule.

65. I have a regular place set aside for studying.

70. I make sure I keep up with the weekly readings and assignments for this course. 73. I attend lecture regularly.

77. I often find that I don't spend very much time on this course because of other activities. 80. I rarely find time to review my notes or readings before an exam.

9. Resource Management: Help Seeking

40. Even if I have trouble learning the material in this lecture, I try to do the work on my own, without help from anyone.

58. I ask the lecturer to clarify concepts I don't understand well.

68. When I can't understand the material in this course, I ask another student in this lecture for help.

75. I try to identify students in this lecture whom I can ask for help if necessary. Source: (Pintrich et al. 1991)

The motivation section consists of 31 items that assess students' goals and value beliefs for a course, their beliefs about their skill to succeed in a course, and their anxiety about tests and exams in a course. The learning strategy section includes 31 items regarding students' use of different cognitive and metacognitive strategies. In addition, the learning strategies section includes an additional 19 items concerning student management of different resources.

Section one of the questionnaire consists of "Motivation" which consists of six scales (Pintrich and De Groot 1990). The first scale; Value Component: Intrinsic Goal Orientation refers to the student's perception of the reasons why the student is engaging in a learning task. The second scale; Value Component: Extrinsic Goal Orientation, refers to the degree to which the student perceives him/herself to be participating in a task for reasons such as grades, rewards, performance, evaluation by others, and competition. Thirdly, Value Component: Task Value differs from goal orientation and refers to the student's evaluation of the how interesting, how important, and how useful the task is, and two questions "What do I think of this task?" and "Why am I doing this?" are asked to determine the task value as high task value should lead to more involvement in one's learning. The fourth scale; Expectancy Component: Control of Learning Beliefs refers to students' beliefs that their efforts to learn will result in positive outcomes. The fifth scale; Expectancy Component: Self-Efficacy for Learning and Performance, assess two aspects of expectancy: expectancy for success that refers to performance expectations, and relates specifically to task performance and expectancy as self-efficacy is a self-appraisal of one's ability to master a task. And lastly, Affective Component: Test Anxiety, which has been found to be negatively related to expectancies as well as academic performance. Test anxiety is thought to have two components: a worry, or cognitive component, and an emotionality component. The worry component refers to students' negative thoughts that disrupt performance, while the emotionality component refers to affective and physiological arousal aspects of anxiety.

Section two of the questionnaire consists of "Learning Strategies" which consists of nine scales. The first scale; Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Rehearsal involve reciting or naming items from a list to be learned. These strategies are best used for simple tasks and activation of information in working memory rather than acquisition of new information in long-term memory. The second scale; Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Elaboration assist students to store information into long-term memory by building internal connections between items to be learned. Elaboration strategies include paraphrasing, summarizing, creating analogies, and generative notetaking. These help the learner integrate and connect new information with prior knowledge. Thirdly, Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Organization assists the learner to select appropriate information and also construct connections among the information to be learned. Examples of an organizing strategies are clustering, outlining, and selecting the main idea in reading passages and should result in better performance. The fourth scale; Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Critical Thinking refers to the degree to which students report applying previous knowledge to new situations in order to solve problems, reach decisions, or make critical evaluations with respect to standards of excellence. The fifth scale; Cognitive and Metacognitive Strategies: Metacognitive Self-Regulation refers to the awareness, knowledge, and control of cognition. There are three general processes that make up metacognitive self-regulatory activities: planning, monitoring, and regulating. Planning activities such as goal setting and task analysis assist to activate, or prime, relevant aspects of prior knowledge that make organizing and comprehending the material easier. Monitoring activities include tracking of one's attention as one reads, and self-testing and questioning: these assist the learner in understanding the material and integrating it with prior knowledge. Regulating refers to the fine-tuning and continuous adjustment of one's cognitive activities. Regulating activities are assumed to improve performance by assisting learners in checking and correcting their behavior as they proceed on a task. The sixth scale; Resource Management Strategies: Time and Study Environment, states that students must be able to manage and regulate their time and their study environments. The seventh scale, Resource Management Strategies: Effort Regulation, includes students' ability to control their effort and attention in the face of distractions and uninteresting tasks. The eight scale; Resource Management: Peer Learning has been found to have positive effects on achievement. And finally, Resource Management: Help Seeking, that the student must learn to manage support of others including peers, tutors and lecturers. Prior research indicates that indicates that peer assistance, peer tutoring, and individual lecturer assistance facilitate student achievement. Source: (Pintrich et al. 1991)