Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.35 n.6 Stellenbosch Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/35-6-4339

GENERAL ARTICLES

Decolonisation of history assessment: an exploration

S. D. Godsell

Wits School of Education Witwatersrand University Johannesburg, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3431-2868

ABSTRACT

Although assessment forms a key part of knowledge production in Higher Education spaces, it is rarely brought into the decolonisation conversation. Assessment performs a crucial inclusion/exclusion function. As this function determines formalised recognition of knowledge and proficiency, decolonisation of assessment should be part of decolonial research in Higher Education. Assessment outcomes determine whether and when students will progress and graduate If we focus solely on decolonising pedagogy and content, but rely on existing assessment practises, decolonisation stops at precisely the moment in which students' knowledge is measured.

This article explores decolonising assessment through conceptual research and a case study using assessments and discussions from three History courses in a teacher education programme. This combination allows for the blending of a theoretical approach with some aspects of application, as well as a grounding in student-driven ideas. The case-study data is drawn from class discussions.1

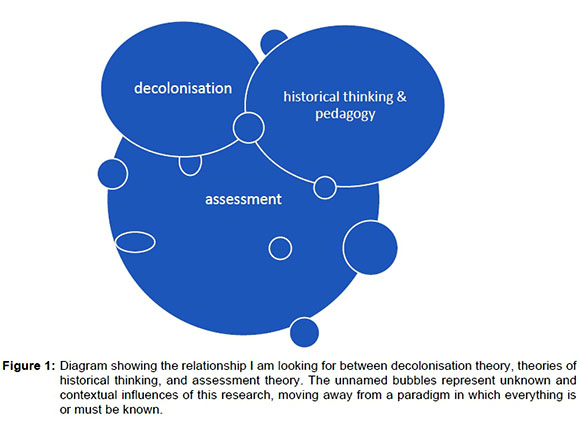

This article brings together principles of assessment, theories of teaching History, and theories of decolonisation. I examine how assessment can disrupt notions of where knowledge is held, built, and displayed. I also try to understand what kinds of assessment students could experience as enabling rather than gate-keeping. This investigation is exploratory, with the aim of opening a field of enquiry, not providing clear and definitive answers. However, as students pass through classrooms each year, there is an urgency to the enquiry. How these questions are approached day to day in the classroom will inform both findings and questions.

Key words: decolonisation, assessment, higher education, history, learning and teaching

INTRODUCTION

"You make me a map of all you know and I'll make you a map of all you don't and we'll see which one holds the bigger truth." Kei Miller, A cartographer tries to map his way to Zion 2021/12/04 11:22:00

Assessment is rarely, if ever, brought into the conversation about decolonisation.2 This may be for multiple reasons, as discussed in the article. Because assessment is what we use to measure summative performance, and so to award degrees or certifications of competence, if we do not bring decolonisation into assessment, it severely undermines the entire project of decolonisation.

This research will look at the question of decolonising assessment from three different perspectives: decolonial theory, assessment theory, and theories of history education. All these will be brought into conversation with a case study of students' perspectives on decolonising assessment. The aim of this article is not to provide a definitive model, but instead aims to refine what kinds of questions we should be asking about decolonising assessment. The methodology draws together conceptual research, case study, and reflexive auto-ethnography. I bring theories on assessment and decolonisation into conversation with some examples from History lectures in a Bachelor of Education programme in light of the different bodies of theory brought into conversation, to offer some preliminary tools towards decolonising assessment.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND PROBLEM STATEMENT

In recent years, much work has been produced on decolonising education, from Higher Education to curriculum and pedagogy. (Fomunyam 2019; Jansen 2019; Bhambra, Gebrial, and Niçancioglu 2018; Luckett, Morreira, and Baijnath 2019). However, the question of how to decolonise assessment has remained relatively untouched. This article asks: what questions do we need to ask to decolonise assessment? What would a decolonised assessment task look like and attempt to achieve?

METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH DESIGN3

This article is qualitative, with a critical theory paradigm. I am using mixed methods in this article, drawing on conceptual research, and empirical data drawn from autoethnography during a first year, third year, and PGCE4 class, in a Bachelor of Education degree.5

The conceptual research I conducted drew on two methods: drawing together my own ongoing research on the topics of decolonisation, assessment, and historical thinking combined with historical pedagogy. The second was an integrative search with the terms "decolonisation" and "assessment". The results of this show two things: this terminology is insufficient to explore this question, and that assessment has not been brought comprehensively into the intellectual scope of decolonisation. The broader results of this research will be used in a further article, but the immediate results gave only one article on decolonising assessment, which specifically examines assessment bias, rather than assessment structure (Fomunyam 2019, chap. 8).

The case-study data is drawn from three different courses: a third/fourth year History Methodology class (for this study class A); a first year history content class (for this study class B); and a Post Graduate Certificate in Education Social Sciences History class (for this study class C). Most of the case-study data for this course is drawn from classroom discussion with class A; however, assessments from all three classes are discussed. This data was gathered in 2019; for this article, qualitative research is drawn on as examples to support the questions being asked. A thorough data-analysis of assessments and discussions will be drawn on in further research. My third research method is that of reflective teaching, which (Ashwin et al. 2015) introduce as a set of principles for practical teaching methods, but which also provide useful data (Ashwin et al. 2015, 3). These three qualitative research methods provide a methodology for the larger research project that this article forms an entry point to.6

TRACING THE ORIGINS OF THE PROBLEM

"A third-year history method class is frustrated. We are talking about decolonisation. The topic spills out like thousands of tiny spiders hatching. The questions are many but grouped around themes":

"How?": "How do we decolonise a Eurocentric curriculum? How do we hold space in class for the difficult questions that decolonisation involves? How do we equip ourselves for the forays into the unknown, away from the safety of the syllabus? How do we not lose our jobs?"

"Why": "Why has this not been done before? Why should we do this now? Is teaching children this history not just causing them pain? Why do we want to hurt our learners? Why has no one taught us this?"

"What?" "What topics do we teach? What pedagogies do we use? What resources and what do we need to give of ourselves to decolonise the classroom?"

"The conversation goes back and forth, using our classroom and our university as a test space. Assessment only comes in at a tangent: we have to teach them to pass the exam. To pass matric they must know the history the exam needs, not the history we want to teach. If we teach them other things, they will fail. This is mirrored from our classroom into the classrooms they will teach in."

"Bringing the conversation back to our classroom, one of our students mentions the frustration of getting in the 60s with no feedback. They point out that the difference between 64 and 66 is getting into an honours programme - and markers do not consider this difference. There is no clear indication of what is 64 and what is 66, while 65 is a ladder, and 64 is a snake."

"The students become heated. Passionate and angry. They speak about this as gate-keeping, as the reason why the higher echelons of tertiary education remain white."7

Is it through this path that I arrive at the question: How do we begin decolonising assessment?

THE URGENCY OF DECOLONISING ASSESSMENT

"This is the oppressor's language yet I need it to talk to you." (Adrienne Rich, "The Burning of the Paper Rather than the Children", in The Will to Change) (Rich 1971, 15).

The arguments in this article are based on two assumptions: firstly, that decolonisation of tertiary education in South Africa is necessary; and, secondly, that assessment is a necessary part of education Biggs and Tang 2011).

If we accept the fact that assessment is a necessary part of education (in this case tertiary education, with a focus on History), then it follows that if the decolonisation project is to be complete, or even attempted in a meaningful way, this must include all aspects of assessment. The outcomes of summative assessment, for stakeholders such as the university or employers, is (ideally) a guideline to what skills and knowledge students are expected to acquire during their specific degrees (Biggs and Tang 2011). It follows then, that the decolonisation of knowledge needs to be carried through assessments out into the broader society. I draw on education theory and discourse that exists before and outside theories of decolonisation: Biesta writes of a focus on assessment scores as a "medicalisation" of education:

"It is this misguided patience that pushes education into a direction where teachers' salaries and even their jobs are made dependent upon their alleged ability to increase their students' exam scores. It is this misguided impatience that has resulted in the medicalisation of education, where children are being made fit for the educational system, rather than that where we ask where the causes of this misfit lie and who, therefore, needs treatment most: the child or the society." (Biesta 2015, 4).

This argument flows into higher education, perhaps more, with massification (Biggs and Tang 2011), performance management, and pressure to publish research. This, due to the limited number of hours in a day, logically results in less time spent on teaching and on conceptualising decolonised teaching or assessment strategies.

WHY HAS ASSESSMENT BEEN LEFT OUT OF THE DECOLONISATION PROJECT?

One reason for assessment being left out of the decolonisation project speaks to the dual function of assessment (Biggs 2014). Biggs outlines that assessment has to both assess learning for students and for stakeholders. The stakeholder (the neo-liberal university in this case), as discussed above, values an assessment that can produce a certification of skill or achievement. This, then, would need to be valid, reliable, and objective.

Assessment goes to the heart of power in education. And decolonisation (associated with radical change, power dynamics, and social justice (Mashiyi 2020)) challenges who these assessments are constructed for, or more acutely, who is allowed to be "human" or who is dehumanised in this process (Wynter 2003). Decolonisation also produces fear (Maldonado-Torres 2016). It challenges accepted power structures which support education structures as both formalised institutions and businesses, often in a neo-liberal school to capitalist labour pipeline (Vally 2007). By disrupting power-hierarchies in assessment we can question the bodies of knowledge we draw on to assess students, recognised as another important point of decolonisation (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2018). These bodies of knowledge, both theoretical and content, are rooted in Western ideas of who has the capacity to produces knowledge (i.e., who is competent enough and deemed to have both the intellect and power to produce knowledge), and who "is" knowledge (Mkhize "The missing idiom" in Bam, Ntsebeza, and Zinn 2018), and who is capable of consuming knowledge, and what kind of epistemic access they have (Morrow 2009). This article argues that decolonisation is irredeemably limited if it is not also extended to assessment practices as well as content knowledge and then to consider possibilities for decolonising assessment.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

FOUNDATIONS AND FRAMING: NEW and OLD

Many of the concepts this article is built on are not new, and come down to basic and fundamental aspects of knowledge, power, and pedagogy. (Crenshaw 1990; Crenshaw 1988; Cummins 2000; Freire 1996; hooks 1994; Thiong'o 1986) However, these theories have not yet built the world their proponents imagined. So, we need to continue asking these questions in different ways, in this article in relation to assessment.

It is always important to look at what is new about a specific framework: what could decolonisation bring to assessment that previous critical pedagogies did not (feminist pedagogy, queer pedagogy, pedagogies for social justice)? I argue that decolonisation builds on these aspects critical theories, but extends the reach more broadly into understandings of the relationship between power, knowledge, and the making/unmaking of human subject in the moment of coloniality (Wynter 2003).

CRUEL OPTIMISM AND WILFUL SUBJECTS: WHAT MAKES A "FIRST", WHAT MAKES A "FAIL"(URE)

The University holds a particular affect in South Africa in 2019. It is a space where race, class, gender and sexuality are contested. It is also a magic box. You go in; you come out with a degree, a job, and stable income and career. The continuation of this myth perpetuates a cruel optimism (Berlant 2011) that also assumes who our students are and what careers are possible in South Africa in 2019. If we turn our focus from Berlant's cruel optimism to Ahmed's (2014) wilful subjects, we can move more towards what "decolonised" assessment - or at least assessment that is not preparing students for a life that does not exist (has never existed for most African South Africans) could look like, and what it could allow.

This is assessment involving constructive alignment (Biggs 201 4) as well as assessment that is designed for learning as well as of learning and learning-oriented assessment (Carless 2015). However, these theories are located in the realm of assessment theory. Putting them in conversation with decolonial theory, and then theories of historical thinking, produces a different map. Some scholars have been doing this through analysing epistemic access, and students experiences in terms of identity, race, and inclusion or exclusion (Shalem et al. 2013). Also key for my attempts to decolonise assessment is the framework of reflective teaching, which takes into account identity, positionality, affective and emotional dimensions (Ashwin et al. 2015).

Decolonisation is a broad and contested field, with many South African scholars making important recent interventions (Fomunyam 2019; Mashiyi 2020; Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2018). There are important conversations to be had about whether we can seriously use a framework that contests power structures when the same framework has been adopted (co-opted) by power structures that is the neoliberal Historically White University (HWU).

This same argument could be used against me writing this article from my position of power as a settler (white) lecturer in a university. I am taking the position that decolonisation is still a useful framework if we consistently do the difficult work of theorising means of exclusion and inclusion, who is creating the knowledge, who is doing the writing, and what is the aim of the research. The aim of this research is to pull decolonisation into assessment theory, precisely to challenge the power structures inherent in assessment practices in Higher Education. la paperson argues that in the assemblage of the colonial University there exist decolonising machines, people, assemblages, people who are seeking to take the assemblage of the University and subvert pieces, to desire and enact decolonisation in spaces (paperson 2017). I am arguing from this position.

I draw on several key theorists, both local and international, to construct my theoretical framework on decolonisation for this study. Sylvia Wynter, in Unsettling the Coloniality of Being (Wynter 2003), draws on the idea of coloniality being the moment of the making or unmaking of "being", in other words of being human. In this, Wynter explores history, race, gender, power structures created in the moment of colonisation that made one standard of humanity, male, white, rational, and defined by these aspects. I draw on her thinking to argue that the status of "objectivity" in current assessment practices is created around an idea of knowledge (who has created the knowledge, who is made human in the knowledge) and power (who has the power to decided who is human, who is included in the "human" as tested in the assessments) that is fundamentally exclusionary.

My thinking draws extensively on Nelson Maldonado-Torres' Ten Theses of Decoloniality, but particularly in this article using the idea that "decoloniality creates fear" (Maldonado-Torres 2016, 11). This gives an explanation, combined with Wynter, of why assessment has not been included in the decolonisation conversation: it is the seat of institutional power. Questioning the logics of knowledge creation, knowledge testing, and the validity and reliability of assessments (due to questioning ideas of logic, objectivity, and power) creates fear in stakeholders.

Historical methodology overlaps with decolonisation where I draw on Nomalanga Mkhize's chapter "The Missing Idiom" in Whose History Counts: Decolonising South African pre-historiography (Bam et al. 2018). Mkhize argues that African (Black) historians and African knowledge systems have been used as knowledge (mined as raw data) rather than seen as creators of philosophical, refined and sophisticated historical knowledge (Bam et al. 2018, 59). In this my frameworks on history and decolonisation overlap. Mkhize argues that language (idiom) is key to this. For the purposes of this article, I take the questions: Who is the source of the knowledge? Who is the creator of the knowledge? Who holds the power in these relations? And who does the language of the knowledge implicitly or explicitly exclude?

Neo Lekgotla laga Ramoupi and Roland Ndille-Ntongwe make arguments for localised knowledge in a paper arguing cohesion between decolonisation and Africanisation of knowledge (Ramoupi 2012). This is important for epistemic access, as well as the proximity of histories taught to facilitate an engaged historical pedagogy (Wills 2016). Similarly, Akhona Nkenkana argues (2015) that gender must be a key analytical component when thinking about African knowledge production (Nkenkana 2015), drawing together the intersection boundaries of marginalisation (Crenshaw 1990) and mapping this onto knowledge and knowledge production.

Finally, Nomathamsanqa Tisani argues that there needs to be a cleansing, ukuhlambulula, before decolonisation begins (Bam et al. 2018, 31). Tisani explains ukuhlambulula as a process of cleansing, "touching inside and out, the seen and the unseen, screening the conscious and unconscious" (Tisani 2018). For this study, this points to the very ingrained nature of foundational assessment practices, and the "epistemic disobedience" needed to begin to think differently around these. A cleansing could involve interrogating the heart of power-relations of assessment in relation to learning.

The most continuous theoretical framework connecting historical methodology, historical pedagogy, decolonisation, and assessment theory, is continuous student input and allowing this to shape both theory and praxis. This is a key part of keeping the work grounded in decolonial praxis. This article argues that the frameworks we have currently are not only insufficient, but dangerous.

Moving into the History case-study, assessment in History in Higher Education relies primarily on the History essay. History methodology in a Bachelor of Education degree uses more practical assessments in the form of micro-teaching and lesson plans. However, History content remains focused on the essay. The benefits of a history essay as a mode of assessment are the general benefits of writing that induces critical thinking, as well as the benefits of putting together a well-supported historical argument (Monte-Sano 2012). Scholars and students are making headway in decolonising historical knowledge. Learner-centred pedagogies are becoming more important, disrupting the current power hierarchies in tertiary institutions. While this is still mostly aspiration, there are ideas of how to approach it (Ramoupi 2012; Bam et al. 2018).

DISRUPTING POWER, DISRUPTING PERFORMANCE: WHAT QUESTIONS DO WE NEED TO ASK?

How do we incorporate decolonisation into assessment? If we are taking Biggs' concept of constructive alignment, the goals, the content, the pedagogy and the assessment are all fundamentally linked. Thinking through hooks (1994) how do we draw decolonial pedagogies into assessment in ways that disrupt power hierarchies, that are responsive to and learning from the students?

The framing of decolonisation pushes into the episteme, and is based on ideas of who, inside a knowledge system, is human, and who is not (Fanon 2001; Gordon 2011; Maldonado-Torres 2016; Wynter 2003). In the context of a university teacher training programme in 2020 in Johannesburg, South Africa, we need to consider current and historical methods of exclusion and dehumanisation, especially as these (race, class, gender, sexual orientation, ability, among others) were the spaces from which the South African decolonisation movement arose.

The framework for assessment is reliant on assessment being both valid (testing the content that is supposed to be tested) and reliable (that the test could be repeated with similar results). The framework or principles for assessment also relies on assessment testing the content that is supposed to be tested fairly, ensures that the methods implemented by the assessor do not "present any barriers to learners' achievements" and is also free from bias (Carless 2015)

DECOLONISING THROUGH QUESTIONING

This article declares itself more question than answer. The case studies provided attempt to speak to some of the core of principles drawn from my theoretical framework when thinking of decolonising assessment (Luckett et al. 2019). However, in the interests of leaving the project open and expansive (and hopefully garnering critique and collaboration) below is a list of questions I find critical to decolonising assessment. They are fundamental questions about power, pedagogy, and many tie in with many previous waves of educational research and theory:

• Who are our students?

• What are our objectives in relation to our students?

• What assumed skills/ knowledge are expected in this assessment?

• What are the thinking skills we are relying on?

• What is the knowledge body we are drawing?

• Who is allowed to be a producer of knowledge?

• What theoretical framework undergirds this assessment structures/ this assignment?

• What assumptions is this assignment making about who the students are?

• Who do the students need to be to perform well?

• What are the students required to do well in the assignment?

• How does the assignment relate to the students' everyday lives?

• How does the assignment speak to the students desired futures?

• How does the assignment interact with the students' potential futures?

• What blocks are there to succeeding in assignment?

• How clear are the differences between 60 and 65?

• How clear are the differences between 70 and 75?

• How clear is the difference between 47 and 52?

• What parts of the educator are present in this assignment?

• What do the students have to read from the educator to excel in this assignment?

In each of these questions the underlying assumption remains: who is human in this framework and who is not? (Wynter 2003). In my particular context, this can speak to many things, but two crucial (and sticky (Ahmed 2004)) aspects are language of assessment (what advantages does a first language speaker have, for example, implicit or explicit, what is the hidden assessment in the hidden curriculum?) and the snowballing disadvantage of inadequate schooling leaving a student outside of many knowledge structures required by the University. These knowledges are, however, inside important knowledge structures that would allow this student to potentially teach differently in the same context in which they were taught, in a different way, to shift accumulating patterns of disadvantage.

DECOLONISATION IN THE UNIVERSITY; WHAT IS IT, WHAT IT IS NOT

"In all disciplines academics need to ask questions about the nature of the knowers their disciplines set out to shape and whether these are the kinds of knowers needed in Africa and globally for the twenty-first century. It has also become increasingly important to make knowledge meaningful to students' lived experiences in Africa." (Carnell and Fung 2017, 133).

The impulse towards decolonisation has been absorbed into many aspects of the university: university spaces, fee structures, curricula, staffing, and orientation of courses and production of knowledge. In the history curricula, there has been a focus on content and, less explicitly, on pedagogy. It is critical that assessment is drawn into the decolonising conversation as this is how learning and ability are measured. Assessment performs the gatekeeping function of determining which students get degrees, which students fail, and which students are allowed to continue to post-graduate study.

Assessment has an urgency attached to it, as each year a cohort of students pass or fail, get admitted to post-graduate degrees or do not. The decolonisation project cannot be completed (or successful) in universities if the decolonising challenge is not also applied to assessment. Approaching assessment with an explicitly decolonial framework opens paths for questions in different directions: who are assessments designed for? How do we communicate the details of what is expected in an assessment, and how do students experience this communication? How do we bridge or disrupt the power hierarchies so explicit in assessment? What kinds of assessment does a "free, public, decolonised, African university"8 make use of?

If educators do not take the question of decolonising assessment seriously, we are sending the message that decolonisation is not important enough to have an impact on assessment, that it is an "add-on", perhaps inserted to humour the students or in attempts to respond to calls for decolonising knowledge.

However, assessment, historically, has been based on a scientism that reduces students to marks, their degrees to a piece of paper, and their lives to numbers on a spread sheet. We cannot assess without giving marks, as marks are needed to demonstrate the level of knowledge which one is deemed capable of implementing what has been learned in the degree, or not. Institutions enforce this in practice, and in policy.

INSTITUTIONAL ASSESSMENT POLICY

The current assessment policy of the University of the Witwatersrand, adopted by the senate in 2015/2016 states the following as key aims of the assessments conducted at Wits:

• "To be an educational tool to teach appropriate skills and knowledge"

• "To encourage continuous learning and detect learning problems"

• "To determine whether students are meeting, or have met the educational aims and outcomes of a course (including qualification exit-level outcomes where appropriate) and to give students continuous feedback on their progress"

• "To determine levels of competence and to inform students on their current competence"

• "To facilitate decisions relating to student progress"

• "To provide a measure of student ability for future employers"

• "To inform teachers about the quality of their instruction"

• "To allow evaluation of a course" (University of the Witwatersrand 2016).

These guidelines can be separated out into two broad streams. One stream promotes assessment as learning, and for feedback to both students and educators:

• To be an educational tool to teach appropriate skills and knowledge

• To encourage continuous learning and detect learning problems.

The other stream promotes assessment of learning for external stakeholders

• To determine whether students are meeting, or have met the educational aims and outcomes of a course (including qualification exit-level outcomes where appropriate) and to give students continuous feedback on their progress

• To facilitate decisions relating to student progress

• To provide a measure of student ability for future employers.

The question of how to decolonise assessment needs to be posed to both "functions" of assessment. The questions around how and why that needs to be done will be different in each case. This "double duty" (Carless 2015) of assessment has been brought up as a tension, and is increasingly a problem with massification and levels of unemployment (Biggs and Tang 2011). The factors that make students "desirable"9 to employers are changing and not necessarily measured in a degree. Where the university has historically been to educate an elite and small section of society, this has changed to a tertiary education system that needs to be broadly accessible, and provide a much larger group of society recognisable skills for jobs that move the majority of an oppressed population into skilled jobs.

Decolonisation of tertiary education needs to address all aspects of this. And while many have been/are being addressed, assessment has been neglected even though it is a crucial aspect of the whole function of the university. This article has attempted to explore some aspects of what decolonised assessment could look like. Many aspects of this can happen in individual classrooms but the University as a whole decides what counts as assessment that guarantees a certain level of knowledge and competence to award a student a certain degree.

This is potentially a slippery slope argument that can lead to hopelessness, as it has been expressed in my methodology classroom: what is the point of decolonising individual courses, when the assessments are not decolonised? What is the point in decolonising assessments when the universities' criteria are not decolonised? What is the point of decolonising university criteria when the society that graduates will work in, the jobs that they seek, are not decolonised? Rebecca Solnit (2005) urges against this kind of despair, because it is paralysing (Solnit 2005). She reminds us that the spaces we inhabit and work in must be our focus. She talks about change being like mushrooms: there is a fungus that grows from the mother body of the plant that is always dormant in the soil. Taking decolonisation to be an important step in moving towards a more equal society, we practice and work in the spaces we are able.

DECOLONISING KNOWLEDGE TO DECOLONISE THE ASSESSMENT OF IT

"Fifth thesis: Coloniality involves a radical transformation of power, knowledge, and being leading to the coloniality of power, the coloniality of knowledge, and the coloniality of being." (Maldonado-Torres 2016, 23).

"Knowledge as consisting of at least three major elements or coordinates: subject (and subjectivity), object (and objectivity), and method (and methodology). This does not mean that there might be other conceptions of knowledge that do not admit of such a clear differentiation between these terms or that include other terms. The idea is rather that subject, object, and method are key terms in the modern/colonial conception of knowledge and that we have to understand this structure in order to critique it and take whatever is of worth for a decolonial conception of knowledge and understanding." (Maldonado-Torres 2016, 18).

The conceptualisation of a word and therefore the image is linked to the language one conjures that word in. There is a different balance, feel and weight to it simply because the way in which that word-image exists in that culture that produced it has different historical and environmental relationship with that word. Ngugi Wa Thiongo demonstrates this in his seminal book Decolonising the Mind when he wrote:

"The word 'missile' used to hold an alien far-away sound until I recently learnt its equivalent in Gikuyu, ngurukuhi, and it made me apprehend it differently. Learning, for a colonial child, became a cerebral activity and not an emotional experience." (Thiong'O 1986, 16)

CASE STUDIES: EXAMPLES OF ASSESSMENT IN HISTORY METHOD CLASSES

"The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it ... History is literally present in all we do." - James Baldwin - as quoted on the wall of Brooklyn Museum in New York.

There is lively, if limited, debate and interesting action on decolonisation content in History at high school level in South Africa (Wills 2016; Ndlovu et al. 2018; Ramoupi 2012; Bam et al. 2018). Part of this is driven by university-based history scholars - but the debate and Ministerial Task Team appointed to look into making History a compulsory subject, lacks linkages to teacher training programmes. The history lecturers at the Wits School of Education are working as a cohesive team to bring decolonisation into the curriculum in both content and method courses. The methods of the individual lecturers differ, but the impulse comes from the same source: to decolonise the knowledge we are teaching and the knowledge being produced in our classes.

There are three different types of assessment I have used to decentre the assumption of a certain kind of assessment being required to demonstrate knowledge in history pedagogy:

1 : The play

In a first year class of students studying social science, (the combination of history and geography - meaning many of the students had not done history at school and had an active dislike of the subject) we teach a module on the French Revolution at the end of the year. The students do not like it. The French Revolution feels Eurocentric, teaching about the Enlightenment principles that did so much damage to the African continent. However, the students still have to teach this in school, so we need to cover it in our syllabus as a teacher training programme.

The usual form of assessment for this course is an argumentative essay. This takes the format of the students engaging with a large reading pack, engaging with an argument, and drawing on the evidence in the readings to make that argument. The students are often left completely removed from the subject matter, bored, and with little deep engagement in the historical detail. As a method towards acknowledging who and where the students are, I set an assessment that involved the students being grouped, each group given a historical moment in the French or Haitian revolution,10 and them needing to craft a play around it.

The results varied widely: some plays had pink drums and dancing during executions. Some were rather monotone. All engaged with the historical moment, in detail, often using primary sources. The shift in the power dynamics in the assessment was that the students were actively, collaboratively, constructing a historical moment and presenting (teaching) it to the class. There was an ownership of the history, as the students wrote their scripts together in tutorials, and discussed minute details of the revolution alongside big principles of freedom, equality, and justice.

2: The Spiderweb

In this assignment, students were given an essay topic. The assignment was broken down into five stages:

• Find 10 pieces of evidence from the readings to answer the essay question.

• In a group, collectively decide on not more than 15 pieces of evidence to use in your argument.

• Then, the students were given a mock spiderweb laid out on the floor: 6 concentric circles of string, each labelled with one of the 6 thinking levels of Blooms revised taxonomy. The students had to construct their argument on the spiderweb in a group, connecting evidence and thinking levels with pieces of string, building an essay spiderweb.

• Then the students needed to take a picture of the spiderweb and go home and write the essay using their spiderwebs.

• After this they were required to reflect on the process of the assessment.

This attempt at decolonising aimed to disrupt the students' relationship to knowledge: to show them the thinking work they are doing each time they write an essay, to disrupt the idea that the essay writing process in history is a regurgitation of facts with no critical or creative thinking involved.

3: The Take home exam

In the Post-Graduate Certificate of Education course we discussed the students' take home exam. I asked them to be cognisant of the fact that this exam is supposed to prepare them to be History teachers, and to think about the following instructions accordingly. I then asked the students to write down what they would like to be examined on in this course. I collected the papers and we read through the suggestions together. The students then voted (anonymously) for what question they would like to be asked. I had promised at the beginning of the class that I would design the exam around their own questions, unless it seemed that they were setting questions that didn't examine content of the course, or were simply designed to give students high marks without content engagement. Once the votes were collected, we discussed the results, and I designed the exam accordingly. I didn't just use the question with the highest number of votes, but incorporated three questions that, together, examined the content of the course well.

In this, students are given agency in their exam, but I also do not relinquish my work and responsibility to ensure they are fairly and appropriately examined (these concepts are also of course contentious). The students engaged with the exam exceptionally well. Power hierarchies were disrupted in this case by who has the authority to set the assessments which perform such an important gate-keeping function.

The above assessments are merely examples of attempts towards decolonising. None are perfect, and none worked exactly according to plan. I include them as examples in this article towards looking for some concrete examples of attempting to decolonise assessment.

"UKUHLAMBULULA": A CLEANSING OF ASSESSMENT PRINCIPLES (Bam et al. 2018, 28)

"... move towards decolonising education, a reflexive exploration in which I question the geopolitics of knowledge which universalises European thought while subalternising and invisiblising all other epistemes." (Bhambra et al. 2018).

A large part of the decolonising project is examining where knowledge emanates from, where it is geopolitically and geo-temporally. This is generally enters the epistemology in discussions about positionality within the knowledge. The questions elucidated earlier demonstrate a why questioning net to hold the scope of a research project. The examples above show my attempts at applying some of these questions. However, as pointed out in the theoretical framework, decolonising assessment might, eventually, push us to destabilise some core assumptions in assessment.

I have argued in this article that (at the very least) questions need to be asked about our assessments if we are pushing to decolonise them. That we can follow hooks and Freire in seeing students as producers of knowledge, of knowledge in a co-production space (hooks 1994; Freire 1996). That we can follow Tisani in a call for a cleansing of the knowledge canon, and with this the assessment canon, and start on new ground, questioning our assessment methodology as well as content (Bam et al. 2018). We can also follow Mkhize, who alerts us to the missing idiom of African history, being both African languages and the African historians themselves.

This exploration has argued that any decolonisation of the curriculum is severely hindered if there is no attempt to decolonise assessment. A responsive, epistemically diverse curriculum could be one of multiplicity, one of situated knowledge, one in which students see themselves as well as different lenses for the broader world (Griesel 2004; Luckett 2001). Without drawing these aspects into assessment, decolonisation is stunted.

MAPPING PATHWAYS AND DRAWING TOGETHER

"To decolonise is to develop a new cartography, to engage in 'epistemic disobedience'." (Bhambra et al. 2018, 199).

What is invisible and thus unconsciously considered universal? Decolonisation is about power, and, in many ways, so is assessment. Following the disrupted cartography metaphor, what can be done to make assessment less rigid and more fluid.

Firstly, it must be located inside a decolonised pedagogy. Although the content does not have to be decolonised, this would boost the assessment not only from the view of constructive alignment, but also in conditioning thinking, ways of being in the knowledge production space, who generates knowledge and who receives it.

Inside a decolonised pedagogy, the power hierarchies should be disrupted in many ways. The students and teacher are co-facilitators of knowledge production. This is undertaken as a meaningful and serious process: it is not pandering to students, nor is it re-centring one locus of knowledge production for another. It is a space where critical thought, critical consciousness, is a key tool.

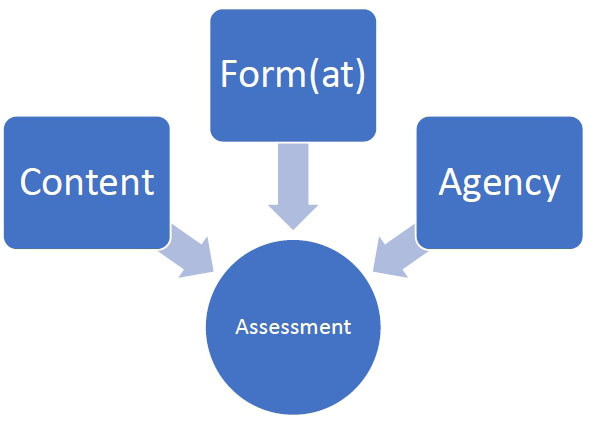

This diagram draws back together some of which has been disassembled in this article: three broad areas which need to be thought through in assessment. Lecturers spend, often, most time thinking through content, some time (at least), thinking through form and format, and very little (generally) thinking through agency. It is my argument that to decolonise we need to pay equal attention to all three, and that all three must be aligned in terms of application and purpose.

The literature I have drawn from to construct the decolonial framework for this project, drawn from diverse scholars, I use to support what is loosely termed "agency" in the above diagram. This is the project of enhancing student agency, epistemic access, and student participation in the various aspects of the assessment. This introduces the dimension of students being co-creators in the process of formulating assessment tasks.

This of course needs to remain balanced with validity and reliability. However, I would argue that an assessment that is exclusionary because of the content or the form is not valid.

CONCLUSION

Decolonising of assessment is an unattended bone in the skeleton of decolonisation of education. Without it, the project of decolonisation will be unfinished. The work of decolonisation remains important while the University remains colonial, governed by invisible, powerful, Eurocentric logic of what knowledge or practices are needed to "pass".

This article has drawn together key theories in decolonisation, assessment, and historical thinking to propose some questions that need to be posed towards decolonising assessment, as well as some possible avenues to explore this. Two key parts of my argument are that decolonisation is urgent and necessary, and that (like in other disciplines) we can build from liberatory, transformative, and critical education theory that already exists. The difficult part of this is to keep questioning the body of knowledge and the power relations created by it.

Decolonisation is a process rather than an act: it is always incomplete and unfolding. We should view this fundamental incompleteness as promising, rather than disheartening, as it allows (and pushes) for constant work and evaluation, constant checking ourselves, and a gravitational pull towards decolonial desires (paperson 2017), as "subservsive intellectuals" (Harney and Moten 2013).

How would we structure decolonised assessment like this into a course? How would we mark it without imposing a hierarchy that limits the work? How would we ensure to maintain learning and measurement of academic rigour? These questions remain part of the broader research project.

NOTES

1 . This research is conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand, protocol number H18/10/10.

2 . As part of the work of reading this article google "Sethembile Msezane's visualartwork 'Kwasuka sukela' enacted at UCT in 2015, while the statue of Cecil John Rhodes, which sparked the #rhodesmustfall movement, was removed". (www.sethembile-msezane.com). Imagine that image as an assessment. Sethembile Msezane is a visual artist working in South Africa. Her works comment on history and culture, among other things. A talk on these artworks may be found on Ted Talks at https://www.ted.com/talks/sethembile_msezane_living_sculptures_that_stand_for_history_s_truths.

3 . A note on positionality: as a settler (white) researcher, looking into decolonisation will always be problematic in various ways, and will always bring in problematic power relations. As a settler (white) South African woman, as well as a lecturer, I hold a particular power position and positionality. I am also in power in a problematic space: a Historically White University (HWU) where hegemonic power is often enacted. My approach to this aspect of the research is to be as open about my positionality and the problems it brings as possible, as well as to try to bring the principles of hierarchy disruption discussed in this article into my thought processes and research methodology. This is not perfect, nor perhaps even sufficient; however, it is the only approach I see as possible for me right now. I welcome criticism, feedback, and ideas.

4 . PGCE: Post-graduate certificate in Education - a one year full-time post-graduate course in Initial Teacher Training.

5 . This research was approved by the ethics committee on 01 February 2019, with the protocol number H18/10/10.

6 . This article does not follow the standard structure of an education research paper. This is intended to be productively disruptive for the reader.

7 . The use of anecdote and poetics in this article is deliberate, and is intended push the article and reader into different reading and thinking modes (Malhotra and Rowe 2013, 123).

8 . This is the phrase eventually decided on by the movement October 6, in the run up to #FeesMustFall in 2015 to express what kind of university was radically desired.

9 . This "desirableness" is part of our neoliberal University system and our neoliberal world, which needs critique in its own rite, however this is beyond the scope of this article.

10 . The French and Haitian revolutions are taught together in tandem

REFERENCES

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 1st Edition. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ashwin, P., D. Boud, K. Coate, F. Hallet, and E. Keane. (Ed.). 2015. Reflective Teaching in Higher Education. Bloomsbury Academic. [ Links ]

Bam, June, Lungisile Ntsebeza, and Allan Zinn. 2018. Whose History Counts: Decolonising African Pre-Colonial Historiography. Re-Thinking African History. African Sun Media. [ Links ]

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Bhambra, Gurminder K., Dalia Gebrial, and Kerem Niçancioglu. 2018. Decolonising the University. Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Biesta, Gert J. J. 2015. Beautiful Risk of Education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315635866. [ Links ]

Biggs, John. 2014. "Constructive Alignment in University Teaching." HERDSA Review of Education 1(July): 5-22. [ Links ]

Biggs, John, and Catherine Tang. 2011. Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 4th Edition. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [ Links ]

Carless, David. 2015. "Exploring Learning-Oriented Assessment Processes." Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education Research 69(6): 963-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9816-z. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, K. W. 1988. Toward a race-conscious pedagogy in legal education. National Black Law Journal 11(1 ). [ Links ]

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1990. "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color." Stanford. Law. Review. 43: 1241. [ Links ]

Cummins, J. 2000. Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Fanon, Frantz. 2001. The Wretched of the Earth. London; New York, New York: Penguin Classics. [ Links ]

Fomunyam, Kehdinga George. 2019. Decolonising Higher Education in the Era of Globalisation and Internationalisation. African Sun Media. [ Links ]

Freire, Paulo. 1996. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Group. [ Links ]

Gordon, Lewis R. 2011. "Shifting the Geography of Reason in an Age of Disciplinary Decadence." TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1(2). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/218618vj. [ Links ]

Griesel, Hanlie. 2004. Curriculum Responsiveness: Case Studies in Higher Education. South African Universities Vice-Chancellors Association. [ Links ]

Harney, Stefano and Fred Moten. 2013. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. 1st Edition. Wivenhoe: Autonomedia. [ Links ]

hooks, bell. 1994. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Jansen, Jonathan. 2019. Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge. NYU Press. [ Links ]

Luckett, K. 2001. "A Proposal for an Epistemically Diverse Curriculum for South African Higher Education in the 21st Century." South African Journal of Higher Education 15(2): 49-61. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v15i2.25354. [ Links ]

Luckett, K., S. Morreira, and M. Baijnath. 2019. "Decolonizing the Curriculum: Recontextualization, Identity and Self-Critique in a Postapartheid University." Reimagining Curriculum: Spaces for Disruption. Stellenbosch: African Sun Media. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. 2016. "Outline of Ten Theses on Coloniality and Decoloniality." Franz Fanon Foundation, October, 37. [ Links ]

Malhotra, Sheena, and Aimee Carillo Rowe. 2013. Silence, Feminism, Power: Reflections at the Edges of Sound. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Mashiyi, N. F. 2020. "Lecturer Conceptions of and Approaches to Decolonisation of Curricula." South African Journal of Higher Education 34(2). https://doi.org/10.20853/34-2-3667. [ Links ]

Miller, K. 2014. The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion. Carcanet Poetry. [ Links ]

Monte-Sano, Chauncey. 2012. "What Makes a Good History Essay? Assessing Historical Aspects of Argumentative Writing." Social Education 76(6): 294-98. [ Links ]

Morrow, Wally E. 2009. Bounds of Democracy: Epistemological Access in Higher Education. HSRC Press Cape Town. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, Sifiso Mxolisi, Sekibakiba Lekgoathi, Amanda Esterhuysen, Nomalanga Naledi Mkhize, Gail Weddon, Luli Callinicos, and Jabulani Sithole. 2018. Report of the History Ministerial Task Team for the Department of Basic Education. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Basic Education. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. 2018. Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and Decolonization. Routledge. [ Links ]

Nkenkana, Akhona. 2015. "No African Futures without the Liberation of Women: A Decolonial Feminist Perspective." Africa Development 40(3): 41-57. [ Links ]

paperson, la. 2017. A Third University Is Possible. 1st Edition. University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Ramoupi, Neo Lekgotla Laga. 2012. "Deconstructing Eurocentric Education: A Comparative Study of Teaching Africa-Centred Curriculum at the University of Cape Town and the University of Ghana, Legon." Postamble 7(2): 1-36. [ Links ]

Rich, A. 1971. The Will to Change: Poems 1968-1970. 2nd Printing edition. W. W. Norton & Company. [ Links ]

Shalem, Y., L. Dison, T. Gennrich, and T. Nkambule. 2013. "'I Don't Understand Everything Here ... I'm Scared' : Discontinuities as Experienced by First-Year Education Students in Their Encounters with Assessment." South African Journal of Higher Education 27(5) : 1081-1098. [ Links ]

Solnit, Rebecca. 2005. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. Unknown edition. New York: Berkeley, Calif.: Nation Books. [ Links ]

Thiong'O, N. W. 1986. Decolonising the Mind. Heinemann. [ Links ]

University of the Witwatersrand. 2016. S2018/1462 SENATE STANDING ORDERS ON THE ASSESSMENT OF STUDENT LEARNING. http://intranet.wits.ac.za/exec/registrar/Standing%20Orders/SSO%20-%20Assessment%20of%20Student%20Learning%20%202018.pdf#search=assessment%20policy [ Links ]

Vally, Salim. 2007. "From People's Education to Neo-Liberalism in South Africa." Review of African Political Economy 34(111): 39-56. [ Links ]

Wills, Lindsay. 2016. "The South African High School History Curriculum and the Politics of Gendering Decolonisation and Decolonising Gender." Yesterday and Today 16(December): 2239. https://doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2016/n16a2. [ Links ]

Wynter, Sylvia. 2003. "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation - An Argument." CR: The New Centennial Review 3(3): 257337. https://doi.org/10.1353/ncr.2004.0015. [ Links ]