Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.35 n.6 Stellenbosch Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/35-6-4317

GENERAL ARTICLES

Illuminating the persistence and departures of previously disadvantaged students at an Engineering faculty

M. C. Bladergroen

Faculty of Education University of the Western Cape Cape Town, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1165-2357

ABSTRACT

The low success rate of many students from previously disadvantaged groups endangers the face and fate of many tertiary institutions, hence an Engineering Faculty's explorations into the causes of these students' persistence at and departures from the Faculty. By using the theory of acculturation and agency the research group explored students' opportunity of freedom towards self-actualisation. Three sample groups were used and the noteworthy findings of the persistence groups' questionnaire and the focus group findings were explored. The data suggest that the previously disadvantaged students experience a general sense of isolation and physical segregation.

Keywords: culture, agency, enculturation, social justice, colonisation, previously disadvantaged students, extended degree program

INTRODUCTION

The historical effects of the colonial invasion are deeply-rooted within all South African cultures. The callous divide in the education system brought about an uneven distribution of good schools and tertiary institutions (the site of interest for this articles). However, the emergence of the new democratic South Africa (1994) was expectant with hope for a new and better tomorrow as anticipated by all marginalised South Africans. This held particularly true for previously disadvantaged youth who were now afforded the opportunity to study at a university of choice. Previously disadvantaged individuals include Black Africans, Indians, Chinese South Africans, mixed-race people, women, youths, the disabled, and those living in rural communities (Chinyamurindi 2018)

Twenty-two years into democracy a gloomy future continues to be predicted for a large majority of the previously disadvantaged youth who still bear the effects of an oppressive and ineffective schooling system birthed through the apartheid system (Albertus 2019; History.com editors 2018). Contributing factors include the reality that social and cultural apartheid was never truly relinquished, and that the white bourgeoisie never fully underwent economic restructuring (Chetty 2016). The post-colonial (post-apartheid) regime failed to bridge the divide. In fact, the new democratic dispensation is witness to and is part and parcel of the reproduction and reinforcement of the historical inequitable social structures.

Chetty (2016) further emphasises that the post-apartheid unequal education system is witness to a deepening racial segregation at schools and tertiary institutions. In fact, the broader university's vision to be characterised as an institution of quality and equity through the constant renewal of teaching and learning programmes is not enough to correct the pre-apartheid racial stratification. The low success rate of many students from previously disadvantaged groups (PDAS) endangers the face and fate of tertiary institutions.

It is against this backdrop that this article reports on the factors that influenced the persistence and departures of previously disadvantaged students from an engineering faculty in South Africa. This exploration is guided by the perceived experiences of social justice, equity and equality in a traditional white tertiary institution (Peltier et al. 1999).

RESEARCH CONTEXT

An Engineering Faculty (Faculty), at a South African Tertiary Institution witnessed a disproportionate number of PDAS prematurely terminate their engineering studies and depart from the Faculty. This tendency urged the Faculty to launch an exploration into the key factors contributing to persistence or departure of undergraduate engineering PDAS.

The Faculty teaching and learning context as a space for public goods (i.e., knowledge acquired through learning) is characterised by a rapid rise in lecturer-student ratio, a momentous rise in diverse student groups, and an ever increasing pressure on lecturers to escalate research outputs. Even though the Faculty has been at the forefront of various institutional changes, the aforementioned conditions challenge the Faculty's ability to act as an agent of change.

Nonetheless, each registered student at the institution at large, and correspondingly at this Faculty, is a client paying (equally) for a service rendered by the institution. Furthermore, it is each registered student's independent right to have an equivalent tertiary education and an equal chance to pass and obtain a professional degree (Corson 2006).

Tertiary institutions' mere existence, the continuation of their existence, their national and international reputation demands acknowledgement of the notorious "elephant in the room". That is, Faculty cannot (1) ascribe to the wrongful belief that "demography (composition of a particular population) determines destiny" (Engle and O'Brien 2007), (2) acknowledge that research evidence speaks to the role and impact of institutions and institutional practitioners; (3) recognise point 2 as an indispensable force that sways the experiences of (any) student, even more for students coming from an oppressed contextual background (Santiago and Hensel 2012).

Through the creation of effective opportunities for learning, Faculty aims to explore the causes of the perplexity of student persistence and student departures amongst. However, an investigation into the literature that guides an investigation into PDAS' experiences at a previously "all-white" engineering faculty has presented few immediate results. The resultant step was an exploration and illumination of the complexity of previously disadvantage student persistence and departures at the Faculty.

To conclude, the departure conundrum has been the object of many empirical enquiry. Even more so in an academic engineering context where there is a lack of comparative theoretical formulations of PDAS's ability to persist in their studies or to depart from Faculty. A formulation of the linkages between the interactive factors that may lead to either persistence or departure amongst undergraduate engineering PDAS became a priority.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Shedding light on possible causes for the retention and departure of PDAS engineering students inevitably requires an exploration of those students' experiences at such faculty. The specific experiences (that of the PDAS) occur within an explicit environment (i.e., an engineering faculty within a previously white tertiary institution). Lourens et al. (2014) argue that both the person elements of PDAS, and the instigative elements of the institutional environment (with its own unique culture, objects, people and symbols) in which the PDAS function, have very specific influences on them. These influences directly affects the PDASs experiences of social justice, equity and equality (Walker and Hodges 2008).

CULTURE AND AGENCY

What culture is, what it does and how it develops remain a highly contested and political debate. The ordinary human being, from childhood, undergoes a process of enculturation. By deliberate learning, what they see, hear and experience, even better by growing up in a specific culture, they become the culture; through repetition, perceptions of "who we are" and "who they are" become entrenched, fixed and deeply rooted. The boundaries and behaviours, what is acceptable and what is not; to be an accepted member of that society; to fulfil your role in that society all starts from the day you are born (Kottak 2018). This view was already entertained by Van Gennep (1960) who argued that the celebration of certain rituals and social events confirm the acceptance and approval of an individual into that particular context and culture. Furthermore, he continues to illustrate that each larger society contains within it several distinctly separate groupings.

Accordingly, when someone comes into continuous contact with a host culture, their values, attitudes and behaviours are challenged (called "acculturation"). Cheung-Blunden and Juang (2008) identified four acculturation strategies and also highlighted the main characteristics and impact of these strategies on the individual. The four acculturation strategies are integration, assimilation, separation and marginal. Each one of these strategies can be observed to frame the wellness of the individual in terms of (1) acculturation dimension which will then assist with the (2) psychological adjustment of the individual; and (3) the interaction affect which can subsequently be detected. The degree to which a person maintains her own culture (heritage culture), accepts the host culture, or moves to a third cultural space (a place of mutual learning, discovery and respect) affects the individual's overall well-being.

Two fallacies (according to Archer 1985; 1988; 1995 and 2005) influenced the critical and rigorous investigations into culture and agent, namely (1) the fallacy that cultural properties are homogenous and undifferentiated, and (2) the fallacy that the members of a culture are all seen to be homogenous. Archer (1995) further laments that the complexities of the internal structures directly affect the assimilation capabilities of new structures into a scheme (or culture). Major disruptions within a structure are a direct consequence of a tightly knitted internal structure. As the structures tighten, less and less radical innovations can be accommodated, leading to "fundamental suppression of any novelty" (Kuhn 1962). This "self-protection" or "self-determination" shuts the doors to any outside/foreign invasion and ultimately leads to alienation or, in the South African context, superiority and oppression.

Archer (1987) argues that social theorists treat culture in a homogeneous and all-inclusive manner. That is, members of a culture share the same beliefs, collective representations, central values, ideology, mythology, form of life, etc.). Archer (1995, p.17) goes on to argue that social theorists view culture to be a mere "mover" on the one hand or a mere epiphenomenon (i.e., a secondary effect or by-product) on the other.

Traditional views, accordingly created a spider web consisting of culture and agent, none of which have their own power or independence; that is, they are intrinsically intertwined and one can never be addressed without consideration of (for) the other. For example, in South Africa reference to culture inevitable refers to the whiteness, blackness or brownness (agent) of or within the culture. The agent becomes a bearer and representation of the properties of the culture. Now, irrespective of "whose culture", the opportunity of freedom towards self-actualisation is either removed or disabled so that neither the agent nor the parts can develop or renew freely.

The dominant agents or groups now have the power to supervise the construction of a set of coherent beliefs. These beliefs will be developed according to the aims and objectives of the dominant group. Through indoctrination, colonisation, or the persuasion of technical control, culture is used to control the agent behind the scenes towards a predestined outcome of the dominant power. If not, the dominant powers will use "culture" to exercise containment strategies, i.e., to insulate (protect) the (their) cultural domain.

STUDENT CULTURE AND AGENCY

To explain student persistence, Astin (1970; 1987) put emphasis on student involvement as an indicator of persistence. He argues that the choice to become involved and the intensity of the involvement are good indicators of the willingness and potential of students to persist.

Tinto (1975) and later work of Demetriou et al. (2011) built on these notions and focused on the entry of minority groups (PDAS in our case) into a predominantly white community or context. Tinto (1975) specifically identified two types of integration, namely social integration and academic integration. However, a critique on the work of Tinto (1975; 1987) is that his approach views the PDAS (political majority, contextual minority) group as the villain in the misfortune. That is, the responsibility resides with the student to ensure that the separation, transition and adoption phase occurs smoothly and successfully. The responsibility and role of the institution to deliberately integrate students on organisational, economic and psychological levels are ignored. As a result, a student is destined to "depart" simply because of the baggage/culture he/she carries into the tertiary teaching and learning space. This is ill-conceived as the tertiary institution reassures their clients (the students) that their aims and visions are to be accessible to all members of the South African population who qualify for university admission, and (2) to enriched in its teaching, research and service provision by a representative staff, with an institutional culture that promotes the optimal fulfilment of human potential and characterised by a participative, empowering ethos that exploits language and cultural differences as an asset (Block 2013).

In summary, when an individual adopts a host culture, studies suggest a lower level of experienced depression, fewer reported symptoms, lower symptom distresses and fewer health, social and academic maladjustments. On the other hand, individuals who retain their heritage culture when entering a host culture, experience more symptom-related distresses especially when no exchanges between the host culture and the heritage culture can be found.

AIM

This project aimed to explore very specifically the key factors and their linkages contributing to the persistence or departure of undergraduate engineering PDAS at a South African Tertiary Institution.

In this context curriculum is used in a broad sense, including didactical aspects, curriculum content, as well as the teaching and learning environment. However, focus for this project was placed on the "experienced curriculum". The specific objectives were to:

a. explore the academic experiences of PDAS in the Faculty;

b. explore the students' perceptions of the impact of societal experiences (Braxton 2000) from inside the Faculty (formal face-to-face sessions);

c. explore the students' perceptions of the impact of societal experiences (Braxton 2000) from inside the broader university (including residences and the campus community at large) on their social integration and academic development; and

d. explore the relationship between the PDAS' self-efficacy (e.g., commitment to the university, internal motivation to engage with the curriculum, etc.) and their experienced curriculum.

METHOD

Whilst the sample for the project was chosen based on the traditional view of culture, namely commonalities around which people have developed values, norms, family styles, social roles, and behaviours, the analysis of the data was based on Archer's (1985) proposition that system integration and social integration constitute the ideal approach in social theories to make sense of cultural dynamics and experiences. Where students are enrolled in the BEng programmes at the time of the survey, and

1. who's enrolments are continuous, are referred to as "persistence"; and

2. who transferred to another Faculty, moved to another tertiary institution, or opted out of studying completely are referred to as "departure".

Two data collection methods were used namely a structured questionnaire and focus group discussions.

The structured questionnaire addressed the following areas: social and academic background information, experiences during formal face-to-face sessions (i.e., lectures and consultation with lecturers), tutorials, group work, time spent on studies and outcomes of test and examinations.

SAMPLE

Three sample groups were used, namely the PDAS' persistence group, PDAS' departure group and a control group (non-PDAS who meet the persistence criterion). This article only reports on the noteworthy findings of the persistence group questionnaire and the focus group findings. The non-PDAS experiences will be used to ascertain if the PDAS' experiences are unique to them, or whether they are significant in terms of the broader university context and culture.

Students from groups prior to democracy were disenfranchised by the then apartheid government were selected. These are black African, Indian and Coloured students who are citizens of South Africa.

Electronic invitations were sent to all PDAS 2nd to 4th year students. An equal number of non-PDAS were included as a control group. Omitting first year students was built on the assumption that, at the time of data collection, the first year students would not have had sufficient critical views on their experiences at the Faculty. This exclusion was, however, mindful of the works of Yorke and Longden (2008) and Mannan (2007) that suggest that the highest attrition rate is found between the end of first year and the start of second year studies Johnston 1997; Ishler and Upcraft, n.d.). Including the non-PDAS as a control group was to measure the uniqueness of the PDAS' experiences against general experience trends.

Data was collected during lunchtime face-to-face sessions in the electronic classroom at the Faculty. A lunchtime meal packet was made available to all students attending the session (regardless of participation or not). This was done to minimise residence students' developing concerns of missed meals.

The survey was based on the work of Nora and Cabrera (1996), and aimed at measuring the following constructs: experiences and perceptions of: prejudice and discrimination, degree of parental encouragement, academic experiences, social integration, academic and intellectual development, goal commitment, and institutional commitments. Our survey included questions on demographic profile and academic progress.

A Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), or similar, was used to measure the items.

These questions were randomised to minimize question bias and to improve the overall data validity and reliability.

FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS

We anticipated that the surveys might reveal areas of concern, and that the responses might not provide us with sufficient detail to formulate interventions to improve PDAS' persistence. After the questionnaire data were analysed, the data pointed to further elaboration on the key findings.

Invitations were extended to all PDAS and randomly selected non-PDAS to participate in a focus group discussion. Budget constraints allowed a maximum of sixty participants. The first sixty respondents were invited to engage with the researchers

The research team was confronted with the non-PDAS obliviousness (of which the reason is outside the scope of this article) to attend these sessions and opted to continue without the input of the non-PDAS group (Trimble et al. 2005).

The main themes that emerged from the questionnaire were revisited during the focus group conversations.

DATA ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Demography of the participants

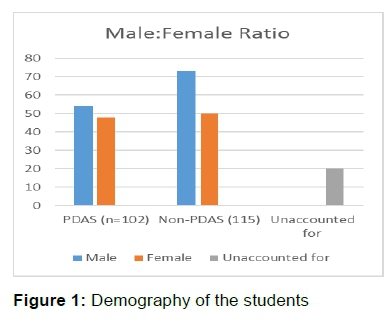

A total of 245 students completed the structured questionnaire. The (disclosed) demography of the participating sample were PDAS (n = 102) and non-PDAS (n = 115) and 28 students remained undisclosed, i.e., not accounted for (See Figure 1). Also, the disclosed gender compilation was 98 female, 127 male participants and 20 remained undisclosed (see Figure 1). It is crucial to note that the general Faculty intake of female-male ratio is skewed with more male intake than female intake. Also, the intake of white males and females are respectively higher than the corresponding PDAS male and female intake (see Figure 2). As a result, out of the 53 PDAS sample, 21.6 per cent came from the coloured communities, 15.5 per cent from the black and 4.5 per cent from the Indian communities.

Academic performance

The data shows an interesting common trend across the various cultural groups (see Figure 2). The participating students indicated that somewhere during their year of study they failed, i.e., 33 students failed in their first year (13.6%), 40 failed in their second year (16.3%), 73 failed in their third year (29.8%) and 137 failed in their fourth year (55.9%). The data suggest that the failure rate increases as the students' progress through their academic years irrespective of their cultural groups.

The Extended Degree Programme (EDP) year extends the undergraduate study by one year. Students who did not achieve the required 60 per cent mathematical score in high school are eligible for entry into the EDP. This equity development programme opens opportunities for capable PDAS who are stifled by socio-economic circumstances to bridge the gap.

An exploration of the gender performances of students from the extended degree programme (EDP) yields interesting results.The contradicition in the questionnaire data suggest that more male than female non-PDAS fail during their EDP. The data further suggest that the EDP creates a bridge towards restoration of previous political injustices and have the capacity to level out existing academic prejudice between PDAS and non-PDAS.

Factors affecting academic progress

Since the non-PDAS opted not to attend the focus group discussion the research team cannot account for and compare those factors affecting their academic progress.

The data suggest that PDAS (black male and -female) experience the biggest sense of distress on three levels, i.e., on a personal, financial and academic level (See Table 1). The causes of these distress make them feel alienated with a general sense of inferiority. These students experience the university support systems to be ineffective to counter these insuperable effects (see Table 2). Students are highly aware that a reduction in their resilience may end up in departure from the Faculty.

S1 : "It is about changing your mind-set and that then encourages your persistence. And if you cannot break through that wall of negativity that floods you all the time you are going to depart."

Interestingly, students view themselves as the responsible agents towards adaptation, i.e., they must "accept/conform" in order to be accepted and to survive. This relates back to Tinto's (1975) approach that change needs to come from the one entering the host culture. The entrenched effect of a cultural system that originated long before the birth of these PDAS are visible in their perceptions. The question arises as "to what extend is it the institutionalised culture that affirms these entrenched view of inferiority and encourage the possibility of departures?"

The emphasised challenging factors to academic progress are (1) financial difficulties, (2) university residence experiences, (3) in-class environment and (4) in-town environment (See Table 1).

Financial constraints

The socio-economic mismatch in the broader context of the country directly dictates the financial socialisations and social consumerization of the students. Both black and coloured students experienced adverse financial constraints ranging from:

Commuting challenges

S2: "My parents cannot afford the petrol to come and pick me up to go home, but to go is everything to me, but then there is no money or anything like food for the week if I'm also there."

Family penuries

S3: "The pressure that is on your parents. They say everything is fine but you can feel them going up and down taking loans. So you are always scared to mess up. They always tell you please try and finish in 4 years. I'm trying to handle the pressure. They are now paying through debit order so every month at the end of the month that's when you get calls and they are saying: Tell them this, tell them that, ask for more days."

Lack of basic resources

S4: "The past two years I never had no food at all, but bare minimum, yes. I had a little bit of toast here and there, noodles, or coffee for breakfast. Just so that you could get through the day."

Insufficient external financial support

S5: "My bursary money cannot pay even half of my books. So in my first semester I had no books at all. So I had to get the soft copies on line. But I don't have a personal computer so I end up always in Firga. But it is always noisy there, so I had to cope with that."

Bureaucratic bursar behaviour

The interviews by the bursars made the students experience emotional and psychological victimization increasing the emotional and psychological distresses of an already oppressed and disadvantaged individual.

S6: "... they come after every test and after every exams and they read your results to you and they ask you how do you feel about it. It is quite scary".

Medical expenses

S7: "When I go to lectures I can understand and I can relate. But I am kind of slow when I write. I don't even finish a single exam in time. I tried last year to ask for extra time. And then the financial thing come in. You need to pay for the psychologist to give you the test and the stuff and I didn't have the money. So I couldn't get the extra time."

Psychological constraints

The requirements of some bursars that the bursary holders must give a regular update on their academic performance, and/or repay the bursary upon failure of an academic year have adverse effects on the students' well-being.

S8: "I have a bursary, and the pressure of having a bursary ... like if you fail you have to pay back the bursary. So I'm constantly thinking 'I mustn't fail, I mustn't fail'. People who have a lot of money they have that change of failing, because mommy pays, daddy pays.

But you know that you don't have that options. Sometimes that pressure that you need to perform lead you failing."

"I can relate to what he just said. For people who have enough they are always relaxed and they can work better. But when there is something that is constantly on your mind, bothering you, 'what if, and then you struggle all the time just to overcome that. It creates that tension in your mind."

However, these students showed a high degree of resilience (especially the female PDAS students, see Figure 4) and the responses suggest that, amidst the adverse financial conditions and experiences of affluence amongst their non-PDAS counterparts, that is not the main reason for wanting to abandon their studies (Azmitia et al. 2018).

S9: "I do have a friend that struggled financially and I could see how it affected him. He didn't have a place to stay and food. It was really depressing and it was weighing him down. Nonetheless he kept moving. So I think it is all about 'your why'. He is still studying, and it is really a nice thing to see that he is still moving forward. So I told them I am not the smartest kid on the block, but I work really hard; and I really need a bursary; and I think I would benefit most. He gave the bursary to me."

University residence experiences

The data suggest that the Afrikaans and English speaking non-PDAS are more comfortable in the social context of the university residences and have no problem asking for help or support in the residences.

PDAS female students and Indian students overall experience the university residences as uninviting and hostile (See Table 2). They experience a general sense of apprehension and vulnerability (n=25). Troubling is that they also do not experience the class representatives as an alternative agent to approach for assistance be it academic, social or political (see Table 2).

The socio-political experiences of black PDAS, mostly female, are disconcerting. These experiences range from prejudice, discriminatory words and behaviour to the self and/or friends, racism, and an overall feeling of exclusion. As a result a low level of motivation exists to cultivate friendships across cultural borders.

S10: "(And you didn't think to stand your ground and say: I am paying for this and I have the right to ask if something is unclear to me) In my mind I feel that but I couldn't say that. It would feel too imposing I suppose. I don't know why."

In-class experiences

PDAS "black students" have a general opposing in-class environment to deal with (see Table 2). In the conversation about their in-class experiences the PDAS sample referred to:

a. The time it takes for them to assimilate the information

b. Fear of losing face with fellow students

c. Limited opportunities for pre-preparations

d. Unsupportive influence of various support interventions (e.g., tutorials, n=17)

e. Socialisation with any of the teaching staff

S11: "It is pretty much the same for me. You tend to fall behind pretty early and then they would move on during the next lecture and you would still be behind trying to understand the first section. You don't absorb a lot in class at that point."

The fear of losing face (n=10) are a major contributor to students reluctance to ask questions during face-to-face in-class sessions.

S12: "Also you think you are delaying other students from learning. The lecturer may be explaining something there and they mostly run out of time. Maybe you didn't understand a certain concept she/he did last week and now you are raising your hand; now it means the lecturer must explain things he had done previously. Now for other students who understand they will be bored."

S13: "I didn't see anything happened. It's what you think. What if everyone in the class understands and I'm the only one not understanding. You don't think that you are at that level [high] as yet. It kind of put pressure on you."

Opportunities for pre-preparations and the unsupportive influence of various support interventions (e.g., tutorials, n=17) was one the most highlighted challenges:

S14: "There is not much support with revision lectures and tutoring. It is very difficult to find help. Last semester in chemical engineering I needed so much help; I emailed my lecturer and there are just so much time that the lecturer is available and the demis as well. It would actually be nice to have actual tutors as well. Tutors that you can go too for help."

S15: "[So you want more assistance in your second year?] Yes and to have individual tutors as well. I think it's just difficult to find someone in second year. And it is difficult to email the dean and ask if there is someone in second year to help me. So besides the lecturer and the demi's there is no one on the university's side. So I have to find friends or people in a higher grade and ask them if they can help me."

Various support services have been put in place for the support of all students. Two of these services (residential mentors and class representatives) are occupied by fellow students. Except for the English speaking non-PDAS the entire cohort experienced these two services as inefficient. That was in addition to male PDAS' discomfort with the Centre for Student Counselling and Development (CHCD) services. These experiences are open for further explorations. But it is safe to say that the impact of the ECP lessens as the PDAS academic years continue.

All students experienced lecturers as approachable outside or after lectures (n=11) (See Table 2). Yet none of them developed a close relationship with any of the teaching and teaching support staff members. In fact, the black PDAS experience prejudice from both lecturers and fellow students. They also do not feel comfortable to ask questions either in class (all accept one female PDAS) and in the university residences. The data suggest that the male PDAS students (particularly the black male PDA students) are hard hit (see Table 1) by the flawed experiences both in- and outside of class.

S16: "Preferred one-on-one action because it's easier to go after the lecture and go: 'Sorry Sir', because than you don't look stupid in front of everyone you only look stupid in front of one person. But then you go there and you can just ask him after the lecture. But then everyone goes there and you don't have time and then you walk away."

S17: "I asked the lecturer once in a tutorial and he was treating me like: 'you should know this'. Now I lack the confidence to ask because what if he feels like I should know this."

S18: "In cases where the groups were chosen for us it will be with white people. And when they look at you it's like: 'Oh you black' and you are a girl, because most girls don't do engineering. And then it's like: 'mm this one is stupid'. Really, even when they ask you a question they expect you not to know the answer."

Students also show a high sensitivity to lecturers' non-verbal communication (n=11):

S19: "I'm beginning to get the sense that lecturers may think: 'I need to finish this. I have a plan for the day for the week and If I do not complete this I will gradually fall behind'. So it is not: 'My students need to understand this'."

S20: "It depends a lot on the lecturer. Some lecturers give off that vibe that you don't want to ask them a question. While other lecturers are very open and when you go to them they would sit down with you and tell you this is where you are and this is why you don't understand this properly."

There is the supposition with lecturers that the theory visited during face-to-face lecture sessions will be revisited during the three hour tutorial sessions. However, the PDAS experience the tutorials also as a daunting space, and find themselves between a rock and a hard place.

A dichotomy also exists where students on the one hand view the town as inviting and a home-away-from-home. However this dichotomy is extraordinary as some PDAS "crossed-over", i.e., outright rejecting their own socio-cultural background, and embracing the context of the "other".

S21: "Yes. In-between, it is home away from home. I feel comfortable here at ..."

S22: "I'm technically homeless and the fact that I've got a room and food somewhere; to me that is amazing. Every time when I come back from my friends place after holiday, ya I'm here. I don't have this where I come from. This is so amazing, so for me I literally feel like this is home."

In-town environment

S23: "Now that I'm here I see the flaws in the young black men at home. I was very closed off to the world. I only knew my blackness. I was not aware of different cultures. I was not aware of different people, different ways of thought, different beliefs and how to handle them. So when I got here I Was like: Wow, this blackness that I am so proud of, an Indian can be proud too; and that would be fully justified and I will have to accept them as a human as I am a human. I've got to accept different cultures. I had to get over racism. That was something that was planted in me, and when I got here I couldn't see it. I accepts people for who they are, and I got to grow and be an actual person. As much as I knew I as a Xhosa man it didn't mean I had to impose my beliefs on someone else. I thought I had an open mind; but once I got here, my mind is really open. I consider myself a truly open-minded individual and I've grown to very high heights."

S24: "When I'm here I feel more like myself... I started my own business and it is growing slowly. Im fine here. I have more space to think and ask my peers where to change. I feel like I've been bought. I really enjoy being here. I crossed deep into STB."

On the other hand the PDAS experience the town environment as uninviting and find being there disheartening:

S25: "No. the culture here in STB is very limiting. I don't drink. I stopped drinking. I don't kuier (party) every day. And I'm not in that grouping and I felt very limited because I'm not Christian or any religion so for me ... my summary will be very blunt: You either drink or you go to church, or you do both. And I am in neither of these groups so I always had a group of friends that I belong to, but the city itself: I don't belong here."

CONCLUSION

Opportunities for student persistence are often measured on student involvement and engagement at an institutional level. This project findings highlight how PDAS from an engineering faulty at a previously white university are challenged by racism, exclusion and marginalisation. The students perceive their cultural disposition as a marker for difference and deficit. Owing to the fact that cultural groups were classified according to the colour of their skin, PDAS are experiencing historical entrapment of being "culturally different from white mainstream" which coincidently was/is regarded as "culture free".

Culture in the Faculty space is used to differentiate minorities from the "rest of the academic society". To have a culture is to be deficient and in a subordinate position. Culture is not used to describe the variance in the overall population, nor as a neutral descriptor for heterogeneity, but rather culture is used as a paradoxical measure of deficiency and as an area where "intervention is required".

The PDAS are of the opinion that Faculty perceive culture as the norms, values, roles and behaviours of a particular group, and not that culture produces the norms, values, roles and behaviours of a particular group. The culture and cultural experience of the PDAS are nullified and they experience a lack of interest and/or concern for their existence and social experiences and needs specifically. In fact, they experience a general feeling of isolation and physical segregation. When Faculty focuses on PDAS, they experience the approach as being "the lesser other, the marginalised, and the intruder". PDAS feel objectified, i.e., objectification is used by Faculty and the institution at large to legitimize interventions.

All these perceptions are part of the real-life/lived experiences of the PDAS and act as barriers to full integration into the Faculty culture. Even though the institution has measures in place to help all students to navigate and overcome barriers to learning, it becomes less successful for PDAS whose experienced barriers are entrenched in the institutional culture (Pua, n.d.). The experiences and perceptions of the PDAS point towards the culture where political and sociological injustices were created, executed, reinforced and transmitted from one generation to another, i.e., even into a democratic political context 24 years in existence.

Consequently, the development of a strong affiliation with the institution and Faculty environment is severely incapacitated. For instance, the lack of close personal interactions with academic staff and peers, various forms of rejection, and devaluing and diminishing destabilize the PDAS' cultural capital (i.e., their set of values, beliefs, norms, attitudes, experiences that are supposed to equip them to live in a broader society) and reduce their social integration opportunities. The institutions entrenched (experienced) oppressive culture erodes human capital development and diversification, and counteract efforts to increase and improve the capacity pool.

Still more significant is the under-representation of females in the engineering field. To restore the "seeping female pipeline" female PDAS need support on an individual, family, financial, in-classroom and within institutional society level. The focus must be on nurturing, supporting and enabling female students to negotiate the system rather than challenge it. If the aim is to shape the female PDAS' experiences through the social structures, it undermines their being and henceforth regulates their future successes or failures in the engineering course.

Faculty has to make concerted efforts to acknowledge and appreciate the somatic and intellectual skills of PDAS, and utilize these towards academic support and increased retention rates (Knekta and McCartney 2018). If not, PDAS are systemically coerced to spend valuable academic time circumventing unpleasant experiences, change Faculty or drop out of the system (Hoyt and Winn 2004; Redmond et al. 2001).

Even if the institution has a targeted approach (whether it is social integration or system integration), without determined efforts towards structural and ethical changes retention successes will remain low (Zeune 1999; Mitchell 2011). For example, growing the critical masses will generate larger awareness and quality-character of relations. Also, in an era of modernisation, globalisation and decolonisation an institutions relevance to forthcoming prognostications and spawning of a competitive workforce becomes obsolete. Ignorance of the need for all-inclusive and ethically just tertiary education institutions, means that the particular institutional environment intensifies its demise as an accountable, relevant, innovative world class tertiary institution.

Finally, without Faculty and institutional staff critically reflecting on their own cultural biases, assumptions and beliefs (reflexivity), i.e. acknowledging the damaging impact of entrenched cultures of racism within the university (Schendel, 137 in Ashwin and Case 2018) and embracing colleagues of colour, allowing equal opportunities, opening productive dialogue and emerging themselves in the culture of the other to understand and make sense of each other's lived world and lived experiences (transformation), the culture that perpetuates discrimination will continue to be reproduced, reinforced and transmitted, negatively affecting the critical identity, experiences, perceptions and academic performance of both PDA-academic (for future studies) and PDAS at the engineering Faculty.

REFERENCES

Albertus, R. 2019. Decolonisation of institutional structures in South African universities: A critical perspective. Cogent Social Sciences 5(1). [ Links ]

Archer, M. S. 1985. "The Myth of Cultural Integration." The British Journal of Sociology 36(3): 333-353. [ Links ]

Archer, M.S. 1987. The problems of scope in the sociology of education, International Review of Sociology Series 1, 1:1, 83-99. [ Links ]

Archer, M. S. 1988. Culture and Agency. The Place of Culture in Social Theory. Cambridge: UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Archer, M. S. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Archer, M. S. 2005. "Structure, Culture and Agency." In The Blackwell companion to the sociology of culture, ed. M. D. Jacobs, N. W. Hanrahan, and Blackwell Publishing. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. [ Links ]

Ashwin, P. and J. M. Case. Ed. 2018. Higher Education Pathways. South Africa African Undergraduate Education and the Public Good. Cape Town: African Minds. [ Links ]

Azmitia, M., G. Sumabat-Estrada, Y. Cheong, and R. Covarrubias. 2018. "Dropping out is not an option: How educationally resilient first-generation students see the future." In Navigating Pathways in Multicultural Nations: Identities, Future Orientation, Schooling, and Careers. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, ed. C. R. Cooper and R. Seginer, 160, 89-100. [ Links ]

Block, D. 2013. "The structure and agency dilemma in identity and intercultural communication research." Language andIntercultural Communication 13(2): 126-147. [ Links ]

Braxton, J. M. ed. 2002. Reworking the student departure puzzle. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. [ Links ]

Chetty, R. 2016. "Why South Africa's universities are in the grip of a class struggle. The conversation." https://theconversation.com/why-south-africas-universities-are-in-the-grip-of-a-class-struggle-50915. (Accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

Cheung-Blunden, V. L. and L. P. Juang. 2008. "Expanding acculturation theory: Are acculturation models and the adaptiveness of acculturation strategies generalizable in a colonial context?" International Journal of Behavioral Development 32(1): 21-33. [ Links ]

Chinyamurindi, W. T. 2018. "'MIND THE GAP' - Experiences of previously disadvantaged individuals by distance learning: A case of selected UNIISA students in the Eastern Cape." Progressio, South African Journal for Open and Distance 12(2): 223-241. [ Links ]

Corson, D. 2006. "Bhaskar's critical realism and educational knowledge." British Journal of the Sociology of Education 12(2). [ Links ]

Demetriou, C. and A. Schmitz-Sciborski. 2011. "Integration, motivation, strengths and optimism: Retention theories past, present and future." In Proceedings of the 7th National Symposium on Student Retention, ed. R. Hayes, 300-312. Charleston, Norman, OK: The University of Oklahoma. [ Links ]

Engle, J. and C. O'Brien. 2007. "Demography is not Destiny: Increasing the Graduation Rates of Low-Income College Students at large Public Universities." The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED497044.pdf. (Accessed on 14 October 2018). [ Links ]

History.com editors. 2018 Apartheid. https://www.history.com/topics/africa/apartheid. (Accessed 12 October 2018). [ Links ]

Hoyt, J. and B. A. Winn. 2004. "Understanding retention and college student bodies: Differences between drop-outs, stop-outs, opt-outs and transfer-outs." Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice 41(3): 395-417. [ Links ]

Ishler, J. L. C. and M. L. Upcraft. n.d. "The keys to first-year student persistence". https://www.ncsu.edu/uap/transition_taskforce/documents/documents/The Keys to First-Year Student Persistence.pdf. (Accessed 25 February 2016). [ Links ]

Johnston, V. 1997. "Why do first year students fail to progress to their second year? An academic staff perspective". Paper presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, September, 11-14. [ Links ]

Kottak, C. Cultural anthropology: Appreciating cultural diversity. McGraw-Hill Education. [ Links ]

Knekta, E. and M. McCartney. 2018. "What can Departments do to increase Students' Retention? A Case Study of Students' Sense of Belonging and Involvement in a Biology Department." Journal of College Student Retention: Research Theory and Practice 0(0): 1-22. [ Links ]

Kuhn, T.S. 1962. Structure of Scientific Revolutions. The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Lourens, E., M. Fourie, and N. Mdutshekelwa. 2014. "Understanding the experiences of educationally disadvantaged students in higher education." Paper presented in track 5 at the EAIR 36th Annual Forum in Essen, Germany. [ Links ]

Mannan, A. 2007. "Student attrition and academic and social integration: Application of Tintos model at the University of Papua New Guinea." Higher Education 53: 147-165. [ Links ]

Mitchell, S. K. 2011. "Factors that contribute to persistence and retention of underrepresented minority undergraduate students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics STEM." Dissertation. 657. University of Southern Missssippi. http://aquila.edu/dissertations/657. (Accessed 14 October 2018). [ Links ]

Nora, A. and A. F. Cabrera. 1996. "The role of perceptions in prejudice and discrimination and the adjustment of minority students to college". Journal of Higher Education 67(2): 119-148. [ Links ]

Peltier, G. L., R. Laden, and M. Matranga. 1999. "Student persistence in college: A review of research." Journal of College Student Retention 14: 357-375. [ Links ]

Pua, M. n.d. "Success for all: Improving Maori and Pasifika Student Success in Foundation-level Study". http://www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/projects/9247-Airini-final-report.pdf. (Accessed 3 March 2016). [ Links ]

Redmond, B., S. Quin, C. Devitt, and J. Arch. 2001. "A qualitative investigation into the reasons why students exit from the first year of their programme and UCD." http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/Reasons Why Students Leave.pdf. (Accessed 03 March 2016). [ Links ]

Santiago, L. and R. Hensel. 2012. "Engineering attrition and university retention". 4th First Year Engineering Experience FYEE Conference. American Society for Engineering Education. http://fyee.org/fyee2012/papers/1012.pdf. (Accessed 03 March 2016). [ Links ]

Tinto, V. 1975. "Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research". Review of Education Research 45(1): 89-125. [ Links ]

Tinto, V. 1987. Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Trimble, J. E. and G. V. Mohatt. 2005. Coda: "The virtuous and responsible researcher in another culture." In Handbook of ethical and responsible research with ethnocultural populations and communities, ed. J. E. Trimble and C. B. Fisher, 325-334. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Van Gennep, A. 1960. The rites of passage. London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group. [ Links ]

Walker, C. and M. M. Hodges. 2008. "Engaging Students: Retention and Success. Bridging Education in New Zealand." In Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the New Zealand Association of Bridging Educators, ed. L. M. Jovanovic and W. A. Jowitt, 40-45. Factors that affected academic achievement of a group of students in the bridging course Pilot study. 5th - 6th October. [ Links ]

Yorke, M. and B. Longden. 2008. The first year experience of higher education in the UK: Final Report. York, UK: Higher Education Authority. http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/York/documents/resources/publications/FYEFinalReport.pdf. [ Links ]

Zeune, L. 1999. "Margreth Archer on Structural and Cultural Morphogenesis." Acta Sociologica 421: 79-86. Sage Publications, Ltd. [ Links ]