Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.35 n.5 Stellenbosch Nov. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/35-5-4174

Staff Writer. 2020a. "South African Universities Close Early Over Coronavirus Fears." BUSINESSTECH 17 March. https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/382453/south-african-universities-close-early-over-coronavirus-fears/. [ Links ]

Staff Writer. 2020b. "Here's When South African Students Will Return to University." BUSINESSTECH 14 May. https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/398027/heres-when-south-african-students-will-return-to-university/. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa. 2019. "Inequality Trends in South Africa." http://www.geocurrents.info/economic-geography/inequality-trends-in-south-africa. [ Links ]

Stats SA see Statistics South Africa.

Stellenbosch University. 2020. "Data Bundles for Students During Lock-Down Conditions." http://www.sun.ac.za/english/learning-teaching/student-affairs/cscd/Documents/GuidanceforStudentOnlineLearning/Data bundles for students.pdf. [ Links ]

Van den Berg, L. and J. Raubenheimer. 2015. "Food Insecurity Among Students at the University of the Free State, South Africa." South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 28(4): 160-69. [ Links ]

Williams, A., E. Birch, and P. Hancock. 2012. "The Impact of Online Lecture Recordings on Student Performance." Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 28(2). https://ajet.org.au/index.php/AJET/article/view/869. [ Links ]

Woo, K., M. Gosper, M. McNeill, G. Preston, D. Green, and R. Phillips. 2008. "Web-Based Lecture Technologies: Blurring the Boundaries Between Face-to-Face and Distance Learning." ALT-J 16(2): 81-93. [ Links ]

^rND^sBüyükduman^nI.^rND^nS.^sSirin^rND^sChinyoka^nK.^rND^nN.^sNaidu^rND^sCooner^nT. S^rND^sDewey^nJ.^rND^sDominguez-Whitehead^nY.^rND^sDwolatzky^nB.^rND^nM.^sHarris^rND^sFengu^nM.^rND^sFosnot^nC. T.^rND^nR. S.^sPerry^rND^sFox^nR.^rND^sHodges^nC.^rND^nS.^sMoore^rND^nB.^sLockee^rND^nT.^sTorry^rND^nA.^sBond^rND^sJackson^nL.^rND^sJones^nM. G.^rND^nL.^sBrader-Araje^rND^sKhalid^nA.^rND^nM.^sAzeem^rND^sLange^nL.^rND^sLetseka^nM.^rND^nV.^sPitsoe^rND^sLetseka^nM.^rND^nV.^sPitsoe^rND^sLubbe^nS.^rND^sMaboe^nK. A.^rND^sMartens^nR.^rND^nJ.^sGulikers^rND^nT.^sBastiaens^rND^sMittelmeier^nJ.^rND^nJ.^sRogaten^rND^nD.^sLong^rND^nM.^sDalu^rND^nA.^sGunter^rND^nP.^sPrinsloo^rND^nB.^sRienties^rND^sMnguni^nL.^rND^sNgubane-Mokiwa^nS.^rND^nM.^sLetseka^rND^sPitsoane^nE.^rND^nD.^sMahlo^rND^nP.^sLethole^rND^sShoba^nS.^rND^sVan den Berg^nL.^rND^nJ.^sRaubenheimer^rND^sWilliams^nA.^rND^nE.^sBirch^rND^nP.^sHancock^rND^sWoo^nK^rND^nM.^sGosper^rND^nM.^sMcNeill^rND^nG.^sPreston^rND^nD.^sGreen^rND^nR.^sPhillips^rND^1A01^nF.^sWagner^rND^1A01^nT.^sKaneli^rND^1A01^nM.^sMasango^rND^1A01^nF.^sWagner^rND^1A01^nT.^sKaneli^rND^1A01^nM.^sMasango^rND^1A01^nF^sWagner^rND^1A01^nT^sKaneli^rND^1A01^nM^sMasango

GENERAL ARTICLES

Exploring the relationship between food insecurity with hunger and academic progression at a large South African University

F. WagnerI; T. KaneliII; M. MasangoIII

IAnalytics and Institutional Research Unit University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1599-3485

IIAnalytics and Institutional Research Unit University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9479-5868

IIIAnalytics and Institutional Research Unit University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0220-8281

ABSTRACT

Food insecurity has been recognized as one of the key challenges currently affecting students in higher education. However, there has been limited research in South African higher education that has sought to understand the relationship between food insecurity and student success. The current study defined student success as a student meeting the requirements to progress from one year of study to another. The study aimed to understand the relationship between food insecurity and student academic progression. Further to this, it aimed to understand the prevalence of food insecurity, and the characteristics of students most likely to progress. This study was carried out at a large South African university and targeted at the entire 2019 first-time, first year undergraduate student cohort (n=5 356). All eligible students were invited via email to participate in a self-administered, online cross-sectional survey. The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) was used to measure student food insecurity. Data were linked to the end of the year academic progress outcomes, which indicated whether or not students had met the requirements to progress to the following year of study. The survey was completed by 1 612 students, giving a 30 per cent response rate. Overall, nearly a quarter of the students (23%) were found to be experiencing food insecurity with hunger, with 5 per cent experiencing severe hunger. A retention rate of 94 per cent was recorded, and a little over 70 per cent of participants progressed to the second year of study. Student academic progression was found to be significantly associated with food security status (p<0.001), as well as first generation status (p=0.007) and home location (p<0.001) in the bivariate analysis. Further to this, a multivariate analysis revealed that students experiencing little to no hunger were almost twice as likely to progress to the next year of study when compared to those experiencing food insecurity with hunger (Odds Ratio [OR]=1.876; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.454-2.418; p<0.001). The results of this study demonstrated that food insecurity with hunger was negatively associated with student academic progression. This is one of the first, and largest, South African studies to demonstrate this relationship. This work advocates for students experiencing food insecurity with hunger to be prioritised in university student support programmes, such as food security interventions, as this may improve student success.

Keywords: food insecurity, academic progression, student success, hunger, higher education institutions, South Africa, university

INTRODUCTION

Food insecurity among students is a growing concern in South African Higher Education Institutions (HEI's). Studies conducted in the past few years have reported alarming rates of food insecurity (Munro et al. 2013; Sabi et al. 2019; Van den Berg and Raubenheimer 2015; Rudolph et al. 2018; Kassier and Veldman 2013).

Food insecurity is often erroneously thought to be synonymous with hunger (Forman et al. 2018). Food insecurity is certainly related to hunger, however, hunger, refers to a physical feeling and is described by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) as "an uncomfortable or painful sensation caused by insufficient food energy consumption" (FAO 2008, 3). Unlike hunger, food insecurity is not a physical feeling, but is rather a term that is used to describe insufficient access to food that is nutritious, safe, and meeting special dietary requirements (FAO 1996). Therefore, food insecurity heightens the risk of hunger.

Research studies conducted to-date in HEI's have consistently identified students' socioeconomic status as a critical contributor to food insecurity (Munro et al. 2013; Sabi et al. 2018; 2019; Van den Berg and Raubenheimer 2015; Rudolph et al. 2018; Kassier and Veldman 2013). These studies have found that students who are recipients of funding from the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) are at heightened risk of being food insecure when compared to students not receiving NSFAS support (Munro et al. 2013). The NSFAS targets its funding primarily at students coming from working class and poor families (NSFAS 2020).

As a result of the increasing number of students receiving NSFAS funding year on year (NSFAS 2018, 22), HEI's are becoming increasingly accessible to students from low income households, which have a higher likelihood of being severely food-insecure. Such students may lack secure and sufficient financial resources for food. According to research, even though this group of students receives NSFAS support, they are still at a higher risk of food insecurity compared to their peers who do not receive assistance (Sabi et al. 2019; Munro et al. 2013).

International literature exploring links between food insecurity and academic outcomes exists. The prevalence of food insecurity in HEI's is generally lower in the United States of America (USA) when compared to South Africa, with food insecurity rates ranging from 19 per cent to 35 per cent reported in some studies (Van den Berg and Raubenheimer 2015; El Zein et al. 2019; Morris et al. 2016). Similar to South Africa, students found to be food insecure were likely to be receiving financial support through loan facilities (Morris et al. 2016) and were likely to be Black or Hispanic (El Zein et al. 2019).

In their conceptual framework, Sorhaindo and Feinstein (2006, 6), reported that nutrition can impact: 1) cognition - including attention span, memory, concentration; 2) behaviour -including increased aggression and hyperactivity, and 3) physical development - including reduced body mass index and impaired motor skills. Food insecurity especially with hunger, is known to have compounded adverse effects on student learning and wellbeing; students who are hungry often exhibit psychosomatic symptoms, including depression, dizziness, headaches and irritability (Pickett, Michaelson, and Davison 2015, 529), which may lead to poor concentration and low content uptake during learning.

Gaining insights on the links between student food insecurity and student success is imperative, as it is unclear whether the food insecurity of students contributes to South African HEI's continued struggle with low student success rates. The South African Department of Education and Training's (DHET) cohort analyses report released in 2019 suggests that 71 per cent of the student cohort enrolled for 3 year degrees in the 2015 student cohort failed to graduate in minimum time (DHET 2019a, 57). As a result, the Department has called for more research to be conducted by HEI's to understand the possible contributors to the persisting low success rates.

In order to determine the impact of food insecurity on student success, there is a need to define what is meant by student success in the context of this article. Although there is no agreed upon definition of student success, there is consensus that student success represents concepts of student retention, progression and throughput (Cele 2021, 57). In this article, the definition of student success was limited only to student academic progression. Student academic progression was defined as a "student progressing from one academic level to the next" (Nettles et al. 1999, 61). A student was determined as "successful" if they have met the requirements to progress from year of study one to year of study two.

PROBLEM STATEMENT AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Despite the pervasiveness of food insecurity in South African HEI's, its effects on student success is still not well understood. Current evidence coming from studies conducted in South African HEI's suggests that students perceive food insecurity as negatively impacting their ability to learn (Sabi et al. 2019); however, there has been limited work that has objectively explored the relationship between food insecurity and student academic progress in the South African context. A limited understanding of the impact of food insecurity on student success means that HEI's are unable to give students the support they need.

This study therefore aimed to answer the following questions: What is the relationship between food insecurity and student success? What is the prevalence of food insecurity among first year undergraduate (UG) students in a large South African university? What are the characteristics of students who are likely to progress academically?

METHODS

Study setting and design

This study was carried out at a large South African university, with data collected over 6 weeks starting in September 2019. In 2019, the student body of the university was made up of approximately 40 000 students, of which 37 per cent were postgraduate students and 55 per cent were female. This study focused on the entire first-time entering first year UG student cohort, which made up 13 per cent of the student population (5 356). The study was incorporated into the online, self-administered First Year Student Satisfaction Survey targeted at the same first year population.

Study participants and recruitment

Students were eligible to participate if they were UG, first-time entering first year students in 2019, over the age of 18 years and enrolled as full-time students. All eligible students were recruited via email, with each email containing a unique link directing them to the online survey.

Data collection tools

The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) was used to measure food insecurity. The tool was adapted so it would be applicable to both students living in the university residence context as well as those that may have been living off-campus. The HFIAS is a standardised 9-item scale with international applicability (Coates, Swindale, and Bilinsky 2007), and includes a 3-item Household Hunger Scale (HHS) (Ballard et al. 2011). Following data collection, reports from the university data warehouse were extracted using individual identifiers of those that completed the survey. Oracle's OBIEE software (California, USA) was used to extract these reports which contained student demographic information, as well as student academic progress outcomes.

Measuring student academic progression

At the end of each academic year and based on their academic performance, each student registered at the university and pursuing an academic programme, is assigned a progress code. Academic progression was defined as a student in year of study 1 (YOS 1) meeting all the requirements to advance to year of study 2 (YOS 2). Respondents' progress codes were therefore grouped the into two categories: 1) Progression to YOS 2 and 2) No Progression to YOS 2.

Data collection and analyses

Survey data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) hosted at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (Harris et al. 2019; 2009). Data from REDCap were merged with reports from OBIEE and analysed using STATA SE 14 (StataCorp LLC).

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical clearance from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (Medical), Clearance Certificate (M210712), as well as (Nonmedical), Clearance Certificate (H18/09/17). In addition, permission was received from the Office of the Registrar to conduct the study.

RESULTS

Of the participants invited to respond, 30 per cent (1 612 students) completed the survey. Table 1 presents the demographics of students who participated in the survey. The age distribution ranged from 18 to 39 years, with a median of 19 years. Students participating in the study were mostly South African (94%), female (62%), in terms of race, were mostly African (75%), and most were studying towards a qualification in the humanities faculty (31%). Most students described the location of their homes as being in the City or Suburb (44%) or in the Township (32%), with 45 per cent receiving financial support from NSFAS and 48 per cent being first in their family to go to university.

Table 2 shows that 73 per cent of the students were food insecure. Food insecurity was distributed among those that were mildly food insecure (11%), moderately food insecure (24%) and severely food insecure (38%). Of the students participating in the study, 77 per cent experienced little to no hunger, 18 per cent experienced moderate hunger and 5% experienced severe hunger. An analysis of food insecurity together with hunger revealed that nearly a quarter of the students were experiencing food insecurity with hunger (23%).

Results presented in Figure 1 compare the progression and retention rates of the study participants to the entire first-time entering first year UG student cohort of 2019. In terms of progression, a higher percentage of study participants (72%) progressed compared to the entire first year UG student cohort (66%). Furthermore, the student retention rate suggested that study participants had a slightly higher retention rate (94%) when compared to the first year UG student cohort (90%).

The chi-square test of independence was used to determine the nature of the relationship between student retention (whether or not a student re-registered in the subsequent year, 2020) and a number of variables. Results in Table 3 indicate that only gender (p=0.005) and working for pay (p=0.019) were significant in their association with student retention, and all the other variables including food security status and hunger were not significant.

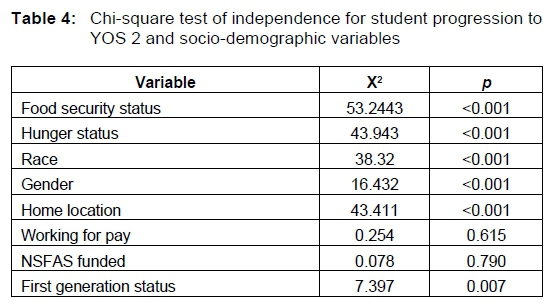

The chi-square test of independence was used to determine the nature of the relationship between student progression and a number of variables. Table 4 shows that food security status, hunger status, race, gender and home location were significant (p<0.001) in their association with student progression. Whether or not a student was first in their family to attend university (first generation status) was also significant (p=0.007).

Student progression had several significant associations. A multivariate analysis was then performed to ascertain the combined effect of the variables of interest, which were food security status, hunger status, race, gender, home location and first-generation status, on the student progression outcome. Table 5 summarises the logistic regression model results.

The variables of interest demonstrated a relationship with student progression on their own (Table 4). However, in the multivariate regression several variables which were found significant in the bivariate analysis were no longer significant (Table 5).

The multivariate model suggests that students experiencing little to no hunger (OR= 1.876; 95% CI 1.454-2.418; p<0.001) were almost twice as likely to progress to the next year of study when compared to those experiencing food insecurity with hunger (Table 5). This group of students was likely to be white (OR=2.510; 95% CI 1.485 - 4.241; p=0.001), female (OR=1.381; 95% CI 1.096 - 1.739; p=0.006) and students whose homes were located in the City/Suburb (OR=1.743 95% CI 1.255 - 2.419; p=0.001).

DISCUSSION

Food insecurity has been recognized as one of the key challenges currently affecting students in higher education (Munro et al. 2013; Sabi et al. 2019; Van den Berg and Raubenheimer 2015; Rudolph et al. 2018; Kassier and Veldman 2013). South Africa has over 1 million students in its HEI's (DHET 2019b, 3). The government continues to implement policies that are targeted at previously disadvantaged groups (NSFAS 2018). This has resulted in HEI's having demographics similar to the one presented in Table 1, where most students, similar to those who participated in this study, are African and female (DHET 2019b, 11; Moses, Van Der Berg, and Rich 2017, 23).

In the current study, the prevalence of food insecurity was found to be 73 per cent, with almost a quarter of these students (23%) experiencing food insecurity with hunger, and 5 per cent experiencing severe hunger (Table 2). These prevalence figures are slightly lower than those published by another South African study which reported food insecurity prevalence as high as 84 per cent when using a multi-item measure of food insecurity, with 60 per cent of the students experiencing food insecurity with hunger (Van den Berg and Raubenheimer 2015). On the other hand, the food insecurity findings from the current study were comparatively high when compared to those presented by Rudolph et al. (2018), who reported food insecurity with hunger at 7 per cent. The discrepancy can be attributed to 1) the two studies targeted different populations, with the current study focusing only on first-time entering first year UG students and Rudolph et al. (2018) focusing on the entire UG cohort; 2) the data was collected in different years, with data for this study collected in late 2019, and Rudolph et al. (2018) in the previous years; and 3) difference in approaches with this study targeting the entire cohort and reaching 30 per cent of first-time entering students and Rudolph et al. (2018) whose sample reached 1 per cent of the population of interest (first year UG students).

The first year of study is widely regarded as crucial to a student's academic performance (Nelson, Duncan, and Clarke 2009). As such, poor experiences during this year have been linked with a higher likelihood of student dropout, hence the often low retention rates and low progression rates in the first year of study (Nelson, Duncan, and Clarke 2009). The retention rates of 94 per cent for the study participants (Figure 1) were slightly higher than the national averages reported by the DHET, (2019a, 57) which indicated drop-out rates of 12-13 per cent (i.e., retention rates of 88-87%) for study programmes that were 3 years and longer. This could be attributed to the responsive support programmes provided to the first year students by this university. It is worth noting that students that were not retained may have enrolled in other institutions. The progression rate of participants reported in this study was 72 per cent (Figure 1), there are limited studies that have explored the year to year progression rates of students (Robinson 2004); however, reports from the DHET (2019a, 57-81) indicate that only 29-38 per cent of graduates complete in minimum time.

When exploring the relationship between food insecurity and student success, student retention was found to not be associated with food security status and hunger (Table 3). In addition, the bivariate analysis indicated that only gender and working for pay were significant in their association with student retention. However, student academic progression was found to be significantly associated with food security status (Table 4). To our knowledge, the current study is one of the first in South Africa that has found significant links between food security and student progression.

Similar studies conducted in the USA have also found clear links between student food insecurity and their academic outcomes. These studies have shown that food insecure students have a higher likelihood to perform poorly academically and take longer to graduate when compared to food secure students (El Zein et al. 2019; Morris et al. 2016). Food insecure students were also shown to have a higher likelihood of scoring lower grade point averages (GPA's) when compared to their food secure counterparts (El Zein et al. 2019; Morris et al. 2016). Furthermore, students experiencing food insecurity were more likely to experience higher levels of stress, had an increased likelihood of experiencing poor sleep and inconsistent eating patterns when compared to their food secure counterparts (El Zein et al. 2019).

In addition to food security status, student academic progression was found to be significantly associated with first generation status and home location in the bivariate analysis (Table 4). Other South African studies had similar findings, these studies found that being a first generation student (Van den Berg and Raubenheimer 2015) and originating from a township (Rudolph et al. 2018) predicted food insecurity. According to (Selesho 2012; Wilson-Strydom 2010), students who are first generation have more difficulty integrating into their new university environment. This suggests that success may improve when students have the support of someone who has been in university. The area which the student is from, including the location and socio-economic status of their communities, has been shown to be a risk factor, with students from some provinces (e.g., Gauteng) and areas (e.g., upmarket areas such as Suburbs and Cities) thought to have a higher likelihood of success (Hundermark 2018). Students from low-income families face financial difficulties, such as difficulties obtaining funds to pay university fees, food, housing, and other requirements such as clothing; these students have been found to be more stressed during their studies (Bojuwoye 2002).

In the current study, the multivariate analysis revealed that students experiencing little to no hunger were almost twice as likely to progress to the next year of study when compared to those experiencing food insecurity with hunger (Table 5). Students experiencing little to no hunger were likely to be white, female with homes were located in the City/Suburb. These results are in agreement with the findings reported in other studies. Studies carried out in South African HEI's, which have generally aimed to investigate the predictors of food insecurity in student populations, have found that African students who are male (Van den Berg and Raubenheimer 2015; Rudolph et al. 2018), pursuing undergraduate studies (Van den Berg and Raubenheimer 2015), and those on extended programmes, in particular (Munro et al. 2013), are more likely to be food insecure.

Unlike in the bivariate analysis, general food security status was found not to be significant in the regression model (Table 5). However, hunger status, which denotes a more severe kind of food insecurity, remained a strong predictor of student progression as demonstrated in the multivariate analysis. The Hunger Scale (Ballard et al. 2011) classifies individuals as experiencing food insecurity with hunger, based on their experience of any (or all) of the following:

(i) "having no food, of any kind in the house, to eat because of lack of resources to get food";

(ii) "going to bed hungry because there was not enough food"; and

(iii) "going a whole day and night without eating anything because there was not enough food".

This suggests that students who experienced food insecurity with hunger, answering "yes" to the questions above, were less likely to progress when compared with students that did not experience hunger, irrespective of their food security status.

LIMITATIONS

The current study used the HFIAS to measure student food insecurity. This tool measures food security and hunger over the past 30 days. Other studies, with similar aims have used these tools (Kassier and Veldman 2013), and we assume that the results reflect the food security status of a student in a typical month.

The socio-economic status of students was not directly measured in the study; however, home location was used as a proxy. Future work exploring the best indirect measure of a students' socio-economic status is warranted.

CONCLUSION

The findings from this study demonstrate that food insecurity with hunger is adversely associated with student academic progression. Students experiencing little to no hunger, irrespective of their food security status, had a higher likelihood of progressing academically, when compared to those who experience food insecurity with hunger. To our knowledge, this is one of the first and largest South African study to demonstrate this relationship. Food insecurity with hunger and its relationship with student success, especially during the first year of study, should be considered as a priority by HEI's.

This work advocates for students experiencing food insecurity with hunger to be prioritised in university student support programmes, such as food security interventions, as this may improve student success. The findings of the current study can be used to inform the formulation of university policies when addressing the challenge of food insecurity with hunger among students.

REFERENCES

Ballard, Terri, Jennifer Coates, Anne Swindale, and Megan Deitchler. 2011. "Household Hunger Scale (HHS): Indicator Definition and Measurement Guide | Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA)." https://www.fantaproject.org/monitoring-and-evaluation/household-hunger-scale-hhs. [ Links ]

Bojuwoye, O. 2002. "Stressful Experiences of First Year Students of Selected Universities in South Africa." Counselling Psychology Quarterly. Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070210143480. [ Links ]

Cele, N. 2021. "Big Data-Driven Early Alert Systems as Means of Enhancing University Student Retention and Success." South African Journal of Higher Education 35(2): 56-72. https://doi.org/10.20853/35-2-3899. [ Links ]

Coates, Jennifer, Anne Swindale, and Paula Bilinsky. 2007. "Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide: Version 3." www.fantaproject.org. [ Links ]

Department of Education and Training. 2019a. "2000 to 2016 First Time Entering Undergraduate Cohort Studies for Public Higher Education Institutions." Pretoria. www.dhet.gov.za. [ Links ]

Department of Education and Training. 2019b. "Statistics on Post-School Education and Training in South Africa." Pretoria. http://www.dhet.gov.za/SiteAssets/StatisticsonPost-School EducationandTraininginSouthAfrica2017.pdf. [ Links ]

DHET see Department of Education and Training.

El Zein, Aseel, Karla P. Shelnutt, Sarah Colby, Melissa J. Vilaro, Wenjun Zhou, Geoffrey Greene, Melissa D. Olfert, Kristin Riggsbee, Jesse Stabile Morrell, and Anne E. Mathews. 2019. "Prevalence and Correlates of Food Insecurity among U.S. College Students: A Multi-Institutional Study." BMC Public Health 19(1): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6943-6. [ Links ]

FAO see Food and Agriculture Organisation.

Food and Agriculture Organisation. 1996. "Rome Declaration and Plan of Action." http://www.fao.org/3/w3613e/w3613e00.htm. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organisation. 2008. "An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security." http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/2357d07c-b359-55d8-930a-13060cedd3e3/. [ Links ]

Forman, Michele R., Lauren D. Mangini, Yong Quan Dong, Ladia M. Hernandez, and Karen L. Fingerman. 2018. "Food Insecurity and Hunger: Quiet Public Health Problems on Campus." Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences 08(02): 668. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9600.1000668. [ Links ]

Harris, Paul A., Robert Taylor, Brenda L. Minor, Veida Elliott, Michelle Fernandez, Lindsay O'Neal, Laura McLeod, et al. 2019. "The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners." Journal of Biomedical Informatics. Academic Press Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [ Links ]

Harris, Paul A., Robert Taylor, Robert Thielke, Jonathon Payne, Nathaniel Gonzalez, and Jose G. Conde. 2009. "Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) - A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support." Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42(2): 377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [ Links ]

Hundermark, Genevieve. 2018. "Who Are Our First-Year At-Risk Humanities Students? A Reflection on a First-Year Survey Administered by the Wits Faculty of Humanities Teaching and Learning Unit in 2015 and 2016." Journal of Student Affairs in Africa | 6(2): 85-97. https://doi.org/10.24085/jsaa.v6i2.3311. [ Links ]

Kassier, Suna and Frederick Veldman. 2013. "Food Security Status and Academic Performance of Students on Financial Aid: The Case of University of KwaZulu-Natal." Alternation 9: 248-64. http://alternation.ukzn.ac.za/Files/docs/20.6/12Kas.pdf. [ Links ]

Morris, Loran Mary, Sylvia Smith, Jeremy Davis, and Dawn Bloyd Null. 2016. "The Prevalence of Food Security and Insecurity Among Illinois University Students." Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 48(6): 376-382.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjneb.2016.03.013. [ Links ]

Moses, Eldridge, Servaas Van Der Berg, and Kate Rich. 2017. "A Society Divided: How Unequal Education Quality Limits Social Mobility In South Africa." http://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/2372-Resep_PSPPD_A-society-divided_WEB.pdf. [ Links ]

Munro, Nicholas, Michael Quayle, Heather Simpson, and Shelley Barnsley. 2013. "Hunger for Knowledge: Food Insecurity among Students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal." Perspectives in Education 31(4): 168-179. [ Links ]

National Student Financial Aid Scheme. 2018. "Title Working Paper 1 Version 2 Compiled by Research and Policy Date of Publication." http://www.nsfas.org.za/content/reports/NSFASAnalysisV3-29032018.pdf. [ Links ]

National Student Financial Aid Scheme. 2020. "NSFAS." 2020. http://www.nsfas.org.za/content/mission.html. [ Links ]

Nelson, K. J., M. E. Duncan, and J. A. Clarke. 2009. "Student Success: The Identification and Support of First Year University Students at Risk of Attrition." Studies in Learning, Evaluation, Innovation and Development 6(1): 1-15. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/28064. [ Links ]

Nettles, Michael T., Ursula Wagener, Catherine M. Millett, and Ann M. Killenbeck. 1999. "Student Retention and Progression: A Special Challenge for Private Historically Black Colleges and Universities." New Directions for Higher Education 1999(108): 51-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.10804. [ Links ]

NSFAS see National Student Financial Aid Scheme.

Pickett, William, Valerie Michaelson, and Colleen Davison. 2015. "Beyond Nutrition: Hunger and Its Impact on the Health of Young Canadians." International Journal of Public Health 60(5): 527-538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0673-z. [ Links ]

Robinson, Rosalie. 2004. "Pathways to Completion: Patterns of Progression through a University Degree." Higher Education 47(1): 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000009803.70418.9c. [ Links ]

Rudolph, Michael, Florian Kroll, Evans Muchesa, Anri Manderson, Moira Berry, and Nicolette Richard. 2018. "Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies amongst Students at University of Witwatersrand." Journal of Food Security 6(1): 20-25. https://doi.org/10.12691/jfs-6-1-2. [ Links ]

Sabi, Stella C., Unathi Kolanisi, Muthulisi Siwela, and Denver Naidoo. 2019. "Students' Vulnerability and Perceptions of Food Insecurity at the University of KwaZulu-Natal." South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition June: 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/16070658.2019.1600249. [ Links ]

Sabi, Stella C., Muthulisi Siwela, Unathi Kolanisi, and Denver K Naidoo. 2018. "Complexities of Food Insecurity at the University of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa: A Review." Journal of Consumer Sciences 46 (July 2017): 10-18. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/jfecs/article/view/179301. [ Links ]

Selesho, Jacob M. 2012. "Making a Successful Transition during the First Year of University Study: Do Psychological and Academic Ability Matter?" Journal of Social Sciences 31(1): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2012.11893009. [ Links ]

Sorhaindo, Annik and Leon Feinstein. 2006. What Is the Relationship between Nutrition and Learning? Journal of the HEIA Vol. 13. London. www.learningbenefits.net. [ Links ]

Van den Berg, Louise and J. Raubenheimer. 2015. "Food Insecurity among Students at the University of the Free State, South Africa." South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 28(4): 160-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/16070658.2015.11734556. [ Links ]

Wilson-Strydom, Merridy. 2010. "Traversing the Chasm from School to University in South Africa: A Student Perspective." Tertiary Education and Management 16(4): 313-325. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2010.532565. [ Links ]

^rND^sCele^nN.^rND^sEl Zein^nAseel^rND^nKarla P.^sShelnutt^rND^nSarah^sColby^rND^nMelissa J.^sVilaro^rND^nWenjun^sZhou^rND^nGeoffrey^sGreene^rND^nMelissa D.^sOlfert^rND^nKristin^sRiggsbee^rND^nJesse Stabile^sMorrell^rND^nAnne E.^sMathews^rND^sForman^nMichele R.^rND^nLauren D.^sMangini^rND^nYong Quan^sDong^rND^nLadia M.^sHernandez^rND^nKaren L.^sFingerman^rND^sHarris^nPaul A^rND^nRobert^sTaylor^rND^nBrenda L.^sMinor^rND^nVeida^sElliott^rND^nMichelle^sFernandez^rND^nLindsay^sO'Neal^rND^nLaura^sMcLeod^rND^sHarris^nPaul A^rND^nRobert^sTaylor^rND^nRobert^sThielke^rND^nJonathon^sPayne^rND^nNathaniel^sGonzalez^rND^nJose G.^sConde^rND^sHundermark^nGenevieve^rND^sKassier^nSuna^rND^nFrederick^sVeldman^rND^sMorris^nLoran Mary^rND^nSylvia^sSmith^rND^nJeremy^sDavis^rND^nDawn Bloyd^sNull^rND^sMunro^nNicholas^rND^nMichael^sQuayle^rND^nHeather^sSimpson^rND^nShelley^sBarnsley^rND^sNelson^nK. J.^rND^nM. E.^sDuncan^rND^nJ. A.^sClarke^rND^sNettles^nMichael T.^rND^nUrsula^sWagener^rND^nCatherine M.^sMillett^rND^nAnn M.^sKillenbeck^rND^sPickett^nWilliam^rND^nValerie^sMichaelson^rND^nColleen^sDavison^rND^sRobinson^nRosalie^rND^sRudolph^nMichael^rND^nFlorian^sKroll^rND^nEvans^sMuchesa^rND^nAnri^sManderson^rND^nMoira^sBerry^rND^nNicolette^sRichard^rND^sSabi^nStella C^rND^nUnathi^sKolanisi^rND^nMuthulisi^sSiwela^rND^nDenver^sNaidoo^rND^sSabi^nStella C^rND^nMuthulisi^sSiwela^rND^nUnathi^sKolanisi^rND^nDenver^sK Naidoo^rND^sSelesho^nJacob M^rND^sSorhaindo^nAnnik^rND^nLeon^sFeinstein^rND^sVan den Berg^nLouise^rND^nJ.^sRaubenheimer^rND^sWilson-Strydom^nMerridy^rND^1A01^nJ. M.^sOntong^rND^1A01^nS.^sMbonambi^rND^1A01^nJ. M.^sOntong^rND^1A01^nS.^sMbonambi^rND^1A01^nJ. M^sOntong^rND^1A01^nS^sMbonambiGENERAL ARTICLES

An explortory study of first-year accounting students' perceptions on the socio-economic challenges of the transition to emergency remote teaching at a residential university

J. M. OntongI; S. MbonambiII

ISchool of Accountancy Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5097-8988

IISchool of Accountancy Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6122-6458

ABSTRACT

For many higher education institutions, the emergency remote teaching (ERT) environment is unchartered territory. The move to ERT for residential universities during a pandemic has highlighted the necessity of understanding students' needs in order to be able to successfully transition to an ERT environment. Performing an exploratory study, this study aims to identify possible socio-economic challenges to the ERT environment should another pandemic or an extended period of ERT take place. Using a questionnaire, this study obtained the perceptions of first-year accounting students regarding their adaptation to the ERT environment ERT. The findings suggest that a wide lens should be used when assessing residential university students' adaptation to ERT. It appears that lecturers and the content offered may be quicker to adapt to the new learning environment; however, restrictions such as access to resources required for ERT may pose a significant obstacle to students engaging in ERT. The results of this study can be used by course planners to consider the impact of ERT on their students and further to potentially implement interventions or changes to their modules to create a larger area of inclusivity.

Keywords: Emergency remote teaching (ERT), first-year students, pandemic, socio-economic impact

INTRODUCTION

The announcement by President Cyril Ramaphosa on 15 March 2020 declared the COVID-19 pandemic a national state of disaster in terms of the Disaster Management Act (South African Government 2020). In response to this announcement, the Ministry of Higher Education suspended contact lectures and declared an early recess from 18 March 2020 in order to contain the spread of COVID-19 (Staff Writer 2020a). A risk-based plan, as determined by the Department of Higher Education, stipulated that all higher education institutions were mandated to offer remote online teaching and learning from 1 June 2020 (Staff Writer 2020b). A number of South African universities, including Stellenbosch University, a traditional residential university, commenced with emergency online teaching in the second term of the first semester on 20 April 2020 in an attempt to salvage the 2020 academic year (Du Plessis 2020).

Online courses are defined as those in which the majority of the course content is delivered online (Allen and Seaman 2007, 4). This is related to open distance e-learning (ODeL), which is defined as teaching in a diverse context where students located in different locations are physically separated from their higher education institutions and lecturers. These online courses are facilitated by the use of online platforms such as discussion forums, WhatsApp groups, and online videos (Lehong, Van Biljon, and Sanders 2019, 1). Emergency remote teaching (ERT), however, is described as a temporary shift in the usual instruction delivery method to a different delivery method due to a crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The difference between ERT and ODeL is that for ERT, an educational ecosystem is not recreated but is rather adapted so that there is temporary access to the institution and institutional support that can be set up quickly in an emergency or crisis (Hodges et al. 2020).

Although many students might traditionally study at a home environment, the move away from a face-to-face teaching institution to a completely online ERT environment is unprecedented for students studying at these institutions. For many universities, this ERT environment is unchartered territory; however, the University of South Africa (UNISA), the largest online university in Africa, is prepared to share its expertise in potential ERT environments (Makhanya 2020).

The move to ERT is not without social-economic challenges, resources such as computers, smartphones, internet connectivity is required in order to create an ERT environment. Looking at the internet connectivity landscape, according to the Inequality Trends report released by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), only 42.9 per cent of rural areas had access to Internet connectivity in 2017 (Stats SA 2019, 120). Furthermore, according to the Gini coefficient of South Africa, South Africa is globally placed among the top five most unequal societies globally (Stats SA 2019, 5). South Africa, for the poor, has one of the highest data prices as a large majority of poor South Africans cannot afford to buy data in bulk (Bottomley 2020).

Cognisant of barriers to access to ERT such as the absence of hardware (laptops / computers) for students to access online learning material and the aforementioned data issues, South African universities have implemented multiple measures in order to smooth the transition for South African traditional residence university students to ERT. Two examples of these include Stellenbosch University and the University of Cape Town. Stellenbosch University has provided laptops to socio-economically disadvantaged students through laptop loans charged to the students' accounts. These loans will be reversed upon the return of the laptops by the students at the end of the academic year (Du Plessis 2020). Stellenbosch University also provided data for students using the four major South African mobile network operators (Stellenbosch University 2020) in order to alleviate the high costs of data. The University of Cape Town (UCT) has also provided laptops on a similar loan system implemented by Stellenbosch University and, similarly, data has also been provided to students (Lange 2020).

Other interventions entered into by universities as a direct result of the transition to ERT included certain higher education institutions informing students that they would receive a 100 per cent fee rebate on their 2020 fees should they deregister from their studies by a specific date. This suggests that the difficulties faced by students with reference to emergency online teaching (ERT) are more profound than those of laptops and data costs (Business Insider SA 2020). A stable Internet connection also poses a barrier to ERT as students who live in rural areas are more likely to experience unstable Internet connections (Bangani 2020). Furthermore, mental health remains an issue for students, as their mental struggles are likely to be exacerbated during this period as these students are removed from resources that enable them to cope (Black Caucus at UCT 2020).

It is therefore evident that the socio-economic challenges faced by students are acknowledged and are being alleviated by universities. However, a question that arises is whether the provision of laptops and data is enough to combat other socio-economic difficulties faced by students who lack basic necessities such as food in their homes as this also leads to negative academic outcomes, such as students dropping out (Dominguez-Whitehead 2017, 153).

South African students who come from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds may also have to study in overcrowded homes with household commitments and deal with living in a noisy neighbourhood, which may present hurdles to the transition to ERT. Students who do not come from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds may also be prone to anxiety and stress due to the uncertainty of the revised academic programme (Shoba 2020). This proposes that another element of the socio-economic challenges experienced by students with the transition to ERT beyond that of laptops and data exists. This study, against the backdrop of South Africa, aims to understand the socio-economic hurdles experienced by accounting students at Stellenbosch University in order to understand if any other factors negatively contribute to the transition to ERT.

The main contribution of this research (based on the students' perceptions) will be to understand the perceptions of current South African first-year accounting students at residential university regarding potential socio-economic challenges as a result of the transition to an ERT platform. This is contextualised against the socio-economic impacts of transitioning from traditional face-to-face learning environments to ERT as observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, this study aims to assist course convenors in the planning of their lectures to accommodate emergency online teaching and the impact thereof on students and to allow changes to modules to accommodate flexibility and provide inclusivity despite the students' socio-economic backgrounds.

Although various studies have been conducted to understand the adjustments associated with first-year UNISA students in the absence of a physical campus (Mittelmeier et al. 2019).

This study is of fundamental importance given the scarcity of research on the transition of residential universities to ERT in traditional face-to-face institutions.

The findings of this study could assist in providing insight into the u socio-economic challenges experienced by traditional residential students with reference to the transition to ERT.

The next section of this article provides a review of existing relevant literature on the topic. The literature review is followed by explaining the research methodology utilised, and a discussion of the findings and conclusions of the study.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The purpose of the literature review is to provide an understanding, using existing literature, regarding ERT and online teaching. The literature review identifies what was previously researched to avoid duplication and to build on the gaps identified in previous research (Mbati 2013, 16). This literature review is divided into four parts. It provides the framework for online learning, then addresses some of the socio-economic challenges experienced in online learning, proposes the benefits of online learning, and details ERT responses as observed during a pandemic. Although the literature on ERT is limited, the benefits and socio-economic challenges of online teaching are framed around UNISA as the largest ODeL institution in Africa, this may however differ to the socio-economic challenges of ERT experienced by residential university students, hence highlighting the need for further research on the transition to ERT by residential universities (Letseka and Pitsoe 2013).

Framework for online teaching

Dewey's constructivism learning approach is a theory of observation based on how students learn (Dewey 1986; Hickman, Neubert, and Reich 2009). This means that learners conceptualise and create their education based on their personal experiences and incorporate cultural factors into the syllabus. Constructivists are observers in a way observing reality being formed in daily life or in science. Some of the approaches on this particular issue can be found below: (Dewey 1986; Jones and Brader-Araje 2002).This makes learning dynamic and not rigid as learning takes place at the student's pace (Khalid and Azeem 2012, 170). There are two categories on which constructivists base their theory; the first being the social aspect and the second being individualism. The social aspect requires the student to relate to the syllabus in order to acquire knowledge, and individualism means that learning for the student takes place at a unique pace (Pitsoane, Mahlo, and Lethole 2015, 30).

The constructivism approach also builds cognitive development and focuses on a deeper understanding of the subject matter (Fosnot and Perry 1996). This means that, for students, learning is an active process whereby knowledge is created rather than absorbed and that effective learning allows posing questions for the learner to answer (Fox 2001, 24).

Under the influence of the constructivist learning approach, access to online learning materials allows students to reflect and reinterpret existing knowledge (Cooner 2010, 281). This is an element of the constructivist approach to learning (Mbati 2013, 154).

Another study, comparing students who attended lectures versus students who only consumed online content, showed that online lectures should be used to complement online learning and not substitute it as the students who attended face-to-face learning obtained higher marks than those who simply watched online lecture videos (Williams, Birch, and Hancock 2012, 210). This is in contrast to the aforementioned constructivist approach as it potentially suggests that online lectures cannot replace face-to-face lectures as online lectures can be dull and repetitive to students, while the traditional face-to-face approach is beneficial as the lecturer serves to inspire and motivate the students (Bennett and Maniar 2007). Furthermore, the opportunity to ask questions and involvement in the group experience are suggested to be absent from online learning (Woo et al. 2008, 86). The argument that arises is whether the students perceive online ERT as beneficial or detrimental to their academic progress.

Socio-economic challenges and benefits of experienced in online teaching environment

In order to develop an expectation of potential socio-economic challenges and benefits of ERT as a baseline this study looks to traditional online universities such as UNISA for existing literature. The study however notes that literature on socio-economic challenges of the transition to ERT by residential universities is limited, this we draw inferences from what is deemed to be a comparable mode, the findings of the study will however highlight if differences are noted. UNISA, the largest online learning university in Africa, has been used to examine the socio-economic challenges experienced by its students with reference to online learning (Letseka and Pitsoe 2014, 1944). The first potential challenge that the literature suggests is that students who transition to ERT may be accustomed to lecturers making use of traditional education methods to disseminate information to students and limited blended learning, whereas the ODeL framework, as used by UNISA, uses the constructivist approach to learning, thereby allowing students to learn at their own pace and understand knowledge without direction, which promotes autonomy (Jackson 2007, 336). Another common problem experienced by students is referred to as digital illiteracy, this means that students are not upskilling themselves with reference to technology usage, which could pose a hurdle to the transition to ERT (Ngubane-Mokiwa and Letseka 2015, 5; Maboe 2019, 114).

Other socio-economic challenges experienced by UNISA students include, but are not limited to, social and emotional adjustments faced by students in the absence of a physical campus, literature on the effect of the move to ERT by residential students on a students social and emotional behaviour is limited (Mittelmeier et al. 2019).

There are benefits to the transition from open distance learning (ODL) to ODeL teaching methods, it is expected that the ERT environment potentially replicates these benefits. Students are able to access educational information at any time and at any location, thus allowing for greater flexibility (Letseka and Pitsoe 2013, 197). Lecturers are also able to provide feedback to students from any location through on-screen marking. ODeL also hones student-centred learning and thus improves critical thinking skills and contributes to a positive learning environment (Ngubane-Mokiwa and Letseka 2015), thereby supporting the constructivist approach to learning as learners are not passive learners but rather active learners who engage with the syllabi (Letseka and Pitsoe 2013, 197).

ERT responses observed in a pandemic

ERT is a temporary mode of instructional delivery due to a crisis, which has the primary objective of providing access to information to students, not compromising the institutional learning provided to students, and delivering an impermanent solution to online learning, which is designed to return to face-to-face education once the crisis has subsided, as evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. This differentiates ERT from online learning as it differs from a course planned to be implemented and completed using online means (Hodges et al. 2020, 4).

There have been many responses by South African universities in order to complete the academic year as closely as possible to the usual year (Dipa 2020). The move to ERT has focused on devices and Internet access, but not on understanding the students' circumstances, such as the provision of a learning space conducive for online learning (Black Caucus at UCT 2020). Tshwane University of Technology, which is the largest contact university in the country, is considering the cancellation of examinations due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Fengu 2020).

Looking at other socio-economic challenges of students at a residential university moving to ERT, could potentially point at items such as food insecurity at home versus at the residential university. Although studies such as the Van den Berg and Raubenheimer (2015) study highlight food insecurity in South African universities, limited analysis has been performed on the relationship between socio-economically disadvantaged students who face food insecurity at universities and what happens when students are mandated to go home due to the emergency transition to online learning.

A similar study performed in Zimbabwe (Chinyoka and Naidu 2013) on secondary schools was highlighted in addition to a lack of food insecurity, a lack of resources for learning that included electricity, having no desk or table to work on, overcrowded homes, and noisy neighbourhoods were listed as the main hurdles to education for socio-economically disadvantaged learners. The ERT environment therefore requires further investigation as to whether these socio-economic challenges are present in such an environment.

For the purposes of this study, first-year accounting students enrolled in 2020 at Stellenbosch University were involved as participants. Although support in terms of laptops and data has been provided to students from poor backgrounds (Du Plessis 2020), the perceptions of students on whether the issues affiliated with ERT are more profound than laptops and data have not previously been investigated.

This study will therefore add to the existing body of knowledge by providing exploratory insight into the perceptions of residential university students with reference to the socioeconomic challenges they face in the transition to ERT.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This exploratory study utilised a questionnaire to analyse the perceptions of accounting students on the transition to ERT. The population of this study comprised first-year students enrolled in the Financial Accounting module at a South African university during the year 2020. An online web-based survey platform was used to obtain responses.

The survey invitation was sent via email to the enrolled students using email addresses obtained from the class list. The participants completed the questionnaire at their own discretion and had an option to opt out of completing the survey at any point. Email reminders were also sent to participants in order to remind them to complete the questionnaire. Ethical clearance was obtained as per the protocol of the relevant institution.

The questionnaire, shown in Appendix 1, included various questions regarding the perceptions of accounting students of ERT. These questions were separated into various themes. The first theme was with reference to how the participants have adapted to the ERT environment, by analysing aspects such as the manner in which they preferred to access and interact with the online lecture content, thereby requiring the participants to indicate if individualism and the social aspect of the constructivist approach are demonstrated. The second theme provided a more in-depth focus on access to ERT resources such as textbooks, computers, smartphones, and an Internet connection. The third theme evaluated the effect of the home environment on ERT, delving into having the space and time at the participants' homes to support conducive studying.

Each of the questions in these themes required responses on a five-point Likert scale from the participants, where 1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, and 5 = strongly agree. Finally, ranking of the obstacles to ERT required that the participants rank their greatest obstacle to ERT as 1 and their lowest obstacle to ERT as 5.

The findings section commences with a descriptive analysis of the respondents. An analysis of the various perceptions obtained follows.

Findings

The findings section discusses the results of the questionnaire according to the three themes identified in the research methodology. Prior to the themes identified as part of the questionnaire a discussion of the respondents' funding for their studies is done below.

An online web-based survey was used to obtain responses. This was sent to all students enrolled in first-year Financial Accounting modules in 2020 at Stellenbosch University. A total of 121 out of 1 180 potential participants, 10.25 per cent, responded to the survey. As this study forms an exploratory nature of the sample response rate is deemed sufficient.

Funding of studies

As shown in Figure 1, the majority of students who responded to the questionnaire are enrolled in the university with their tuition and study-related fees being funded by their parents. This is followed closely by students on some form of bursary such as the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) or another bursary. A limited number of students were self-funded.

Although the majority of students in this study who responded to the survey were parent/ self-funded, which can potentially be listed as a limitation to understanding the views of students who are arguably in more need, such as NSFAS students, the results of the study were evaluated on an overall basis, as well as further analysing whether a variance exists between the results of bursary-funded students and parent-funded students in order to better understand the needs on all scales. A limitation of this study is that the assumption is made that bursary students on non-NSFAS bursaries are also in need, in order to account for this assumption these students discussion incorporates the overall view of all participants to report the findings on aggregate as well. It is suggested that all students will incur socio-economic challenges during ERT such as the stress and anxiety of uncertainty during ERT (Shoba 2020), and the results of this study will therefore provide valuable insight into a variety of socio-economic challenges across a spectrum of students.

Theme 1: How participants have adapted to the ERT environment, by analysing aspects such as the manner in which they preferred to access and interact with the online lecture content

The findings firstly explore how students perceived ERT versus traditional face-to-face face classroom learning. The results in Table 1 indicate that students are indifferent in terms of whether they prefer online learning to traditional face to face classes, given that content may be rewound and paused as needed. The same mean score of 3 was received from bursary students and parent-funded students. This is also depicted in the comments received from students, where one student, who strongly disagreed with the statement, noted that "Face-to-face lectures are much more understandable than online lectures", versus another student who strongly agreed with the statement by commenting:

"Yes, very true. I really like the fact now studying is in my hands, I get to rewind important points that the lecture mentions. Disturbances from fellow students are avoided."

The reasons provided by students who were neutral to the ERT environment indicated that the traditional classroom creates an approachable environment for students:

"I do agree but I also have the chance to ask questions in class through face to face. Everyone in class will benefit from my question and understand the work better."

Similar comments such as "A video is good but having to ask a question in person is much more understanding" indicate that although items such as emails and discussion forums are available, in-person learning is perceived to be more one on one and accessible. Another respondent noted, "This is an advantage we have, but it is not the same as sitting in class. Learning online takes longer to understand and process even though there are videos, etc.", which indicates that the workload for ERT is perceived to be significantly higher. This was echoed by another student, who noted, "It is easier to do the work at your own pace, but it also takes a lot longer."

It is evident that the constructivism approach, in response to ERT, is experienced how some students who prefer to learn at their own pace, engage with the material with deeper understanding, and experience autonomy in their learning (Büyükduman and Sirin 2010, 55). Other students found that face-to-face lectures were beneficial in that students could ask questions, be motivated by their lecturers, and build knowledge from each other in groups, thereby supporting the theory that traditional lectures enhance the learning experience (Woo et al. 2008).

Both groups of students indicated that they agreed that their lecturers were prepared for the ERT environment. One student noted, "Lecturers are always ready, but because they can't see us, they don't know when we understand it". Similar findings were found with regard to participants' perceptions regarding whether they receive enough educational support from their lecturers and tutors to assist them in the course. However, when asked whether the transition from face-to-face learning to an online lecture platform would not negatively impact their degree, the results showed that the students were indifferent; perhaps leaning towards disagreeing with the statement. It is, however, suggested that ERT's effectiveness is influenced by various other factors and not necessarily the learning content. This finding is echoed in the comments below.

"The transition was hard at first, but I believe the self-discipline I developed would definitely benefit me. The only problem that I think would occur is the effect of the lack of socialising, as I'm studying a high-pressure degree and can't take a break to socialise as I would have in residence, seeing as I have less time and it is harder to get to my friends."

"I am going through an adjustment phase."

"My biggest obstacle right now is motivation since I don't have friends here that are empathising with what I'm doing."

The above comments suggest that intrinsic motivation is required to successfully thrive in an ERT environment, achieve autonomy, and being able to conceptualise knowledge, which support the constructivist learning approach (Martens, Gulikers and Bastiaens 2004, 368).

Theme 2: Focus on access to ERT resources such as textbooks, computers, smartphones, and an Internet connection

The next section of the findings relates to student preferences and accessibility to resources during a period of ERT. The results of the questionnaire for this group of questions are shown in Table 2.

Firstly, when asked if students preferred textbooks in hard copy as opposed to electronic textbooks, the findings suggest that students have a strong preference for hard copy books versus e-books. The main reasoning for this is that students preferred to make notes in their hard copy textbooks. This was noted in a few of the comments:

"Yes, I do, but hard copy textbooks are expensive and my only worry about the soft copy is the damage to the eyes. I still want to have a good eye[sight] after all this."

"I prefer hard copy textbooks as I can make notes on it."

"Other than just preferring hard copies, this online teaching time has me looking at screens much more than I'd like so I have come to prefer things not on a screen."

One participant, however, noted that although they had a strong preference for e-books, they were hesitant to use them due to potential problems occurring:

"Electronic books are better and faster to work through. The only disadvantage to this is of course technical difficulties that could occur."

South Africa as a developing economy presents various network-related problems in terms of Internet connection (Stats SA 2019, 120). Although the university has made data and computers available to all students, Internet connectivity still plays a critical role in a student's ability to engage successfully in ERT (Dwolatzky and Harris 2020). It is noteworthy that the university instituted a laptop programme; access to a computer as reflected in the results should therefore not have been a significant barrier (Du Plessis 2020). The results are therefore unable to gauge that if no such programme had been made available, if similar results would have been noted; this provides an area for future research.

The results of the questionnaire shown in Table 3 indicate a clear difference in access to the Internet between bursary students and parent-funded students, where parent-funded students were noted to have access to a stable Internet connection, while this was less prevalent with bursary-funded students, who were neutral on this matter.

The findings suggest that interventions by the university, such as providing data, have a significant impact on a student's access to ERT, where one student noted, "Yes. As long as the university continue[s] sending data." The unfortunate side of a poor Internet connection is that it appears to be demotivating to students:

"My connection is not fully stable and it really demotivates me when trying to download lecture videos."

Another respondent noted:

"We have two ADSL lines and our area I had always had connectivity issues (and I live in a town). There have been days where I am unable to access the Internet due to connectivity problems."

This suggests that the area where a student lives may result in them being significantly impacted when engaged in ERT; this is an important consideration for policymakers at higher education institutions to consider.

The findings mentioned in this section clearly revealed that rural areas lack certain infrastructure such as internet connectivity, which is consistent with research that purports that Internet instability is prevalent in rural areas, thus providing a barrier to ERT (Bangani 2020). The lack of infrastructure such as internet connectivity based on cell phone towers and fibre/ADSL availability is exacerbated by the geographical location of the rural areas, given that there are mountains, thick bushes, and vastly dispersed houses; thus not making it conducive to Internet infrastructure (Lubbe 2005, 4).

The results further indicated that all students had access to some form of smartphone to view certain content, such as emails. This was, however, not noted to be without limitations for students; for example, one student noted that without the data provided by the university, their smartphone would not give them access to the emergency online content; which echoed by the comments below:

"The data granted by university allowed me to be up to date with emails."

"I live in a small rural town in the Eastern Cape, therefore the Internet connectivity is not the strongest. I do receive data from the university but there is barely signal where I reside, therefore I cannot always access the Internet when needed. In the small town I live in, the water supply is often low, sometimes going for weeks without water in the taps. The electricity is also often cut due to theft of cables and damage to the transformers in town. I do, however, have access to food. My house is also located in the industrial area of town, therefore during the day my surroundings are noisy due to the businesses around me being open such as mechanical workshops and grocery stores. With the stores around my house, there is also the noise of the people going to these places."

"I live on a farm so the Internet can be good one day and very poor another. With living on a farm, people come in and go out a lot and on some days there may be a lot of shouting, which disturb[s] me."

The findings documented above are consistent with the expectation of students in rural areas not having the technological infrastructure to support emergency online learning. Theme 3 of this research focused on the students' home environments; therefore, comments regarding the lack of water, electricity, and noisy conditions are explored in the following section.

Theme 3: Evaluation of the effect of the home environment on ERT, delving into having the space and time at the participants' homes to support conducive studying

ERT requires the majority of students to study from home, which often presents additional socio-economic challenges. The questionnaire was developed to obtain an understanding of the respondents' socio-economic challenges arising from this transition. The results of this aspect are shown in Table 4 and Figure 2. Figure 2 presents five potential obstacles provided to participants to rank in order of which presents the greatest challenge to their transition to ERT. Noisy conditions at home, although it appears to be neutral for both groups, were listed as the number one challenge by all students in terms of ranking.

The findings suggest that there is a wide range of factors that create noisy conditions, such as:

"My siblings tend to make a noise, which make[s] it unable for me to listen to lectures."

"The neighbours can be loud sometimes but not to a great extent where it creates a problem."

"It can be a problem since I don't have a study area, I use the dining room and with younger siblings, it can be disruptive and impact my productivity."

"It is definitely very distracting, as our household does not solely focus on me and my studies.

Everyone in my house [is] working from home and go about their work in different ways."

These findings suggest that larger family environments create significant socio-economic challenges to students; this was reiterated by one student noting less of an impact:

"I am an only child and my parents work. My parents are very respectful of my studies and my studying environment is excellent."

The findings also showed a difference between mean scores for students who are bursary-funded versus parent-funded in terms of distractions such as having to do chores or other responsibilities. Two respondents noted the following:

"When at home, my parents let me do all sorts of tasks and I can't stay up to date with lectures." "It is definitely distracting, as my studies are constantly interrupted to do chores."

The findings indicate that both household responsibilities and noisy conditions at home are a challenge to students during ERT. This shows that, for many students, ERT is not advantageous to their studies compared to being at a residence (Mnguni 2020).

"Due to Coronavirus, everyone in the family has to work from home. This means that my mother and father have noisy conversations on and off the phone all day, and younger siblings have teachers online all day. We also live nearby a construction site. Internet is always slow, but we are privileged to have all basic necessities."

An assumption of this questionnaire is that due to the nature of lockdown during this period of ERT, students completing the survey are engaged in ERT from a home learning environment. Concerning the provision of food and clean clothing at home versus a potentially more structured environment such as a residence, this was not a pervasive problem that affected the students who were not parent-funded or those who were, but as shown in the comment above, basic necessities pose a threat to ERT. This is consistent with the assumption that students from rural areas tend to experience a lack of essential items, such as electricity, that are imperative

for ERT.

The respondents did, however, note that the stress of their parents potentially losing their jobs or lack of income had an impact on their learning. One respondent noted that their income was limited and consequently the availability of food was limited. This is a potential area for concern and requires higher education institutions to consider the effect of a lack of resources on these students' ERT experience. Vulnerable students should potentially be identified and provided with additional resources.

CONCLUSION

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, lecturer at traditional residential universities have moved to ERT; however, there are questions regarding the socio-economic challenges of ERT in the context of South Africa and traditional residential universities adapting to this mode of teaching.

The results of this exploratory study highlight the need to investigate how students are able to adapt to an ERT environment. The findings propose that a wide lens needs to be used when assessing students' adaptation to ERT. It appears that lecturers and content may be quicker to adapt; however, restrictions such as access to resources required for ERT and unfavourable home circumstances may pose a significant hindrance to students' engagement in ERT.

The ranking of the findings signified that items such as learning environments, namely noisy and/or busy environments, and limited Internet access play a larger role in being a potential barrier to successful ERT compared to the availability of online resources. It is suggested that lecturers must consider these findings when developing work programmes, course content, and assessments in order to attempt to provide students with an equitable learning approach given the multitude of potential barriers that may exist. Areas for future research include understanding students' perceptions of ERT in the absence of the provision of data and laptops and students' views on the implementation of a modified approach to ERT taking into account this research. This research contributes to the body of existing literature by providing an in-depth understanding of the needs of students during ERT in a course that offers a predominantly traditional pedagogy and assists course coordinators in order to modify the syllabi to accommodate flexibility and inclusivity.

REFERENCES

Allen, I. E. and J. Seaman. 2007. "Online Nation: Five Years of Growth in Online Learning." https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/survey_report/2007-online-nation-five-years-growth-online-learning/. [ Links ]

Bangani, Z. 2020. "The Digital Learning Divide." https://www.newframe.com/the-digital-learning-divide/. [ Links ]

Bennett, E. and N. Maniar. 2007. "Are Videoed Lectures an Effective Teaching Tool?" http://podcastingforpp.pbworks.com/f/Bennett+plymouth.pdf. [ Links ]

Black Caucus at UCT. 2020. "There Are Alternatives to Pushing Emergency Remote Learning at Universities." Mail & Guardian 1 May. https://mg.co.za/article/2020-05-01-there-are-alternatives-to-pushing-emergency-remote-learning-at-universities/. [ Links ]

Bottomley, E.-J. 2020. "SA Has Some of Africa's Most Expensive Data, A New Report Says - But It Is Better for the Richer." https://www.businessinsider.co.za/how-sas-data-prices-compare-with-the-rest-of-the-world-2020-5. [ Links ]

Business Insider SA. 2020. "UCT Students to Get Full Refund If They Drop Courses by Friday." https://www.businessinsider.co.za/uct-students-to-get-full-refund-if-they-drop-courses-before-friday-2020-6. [ Links ]

Büyükduman, I. and S. Sirin. 2010. "Learning Portfolio (LP) to Enhance Constructivism and Student Autonomy." Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 3: 55-61. [ Links ]

Chinyoka, K. and N. Naidu. 2013. "Uncaging the Caged: Exploring the Impact of Poverty on the Academic Performance of Form Three Learners in Zimbabwe." International Journal of Educational Sciences 5(3): 271-81. [ Links ]

Cooner, T. S. 2010. "Creating Opportunities for Students in Large Cohorts to Reflect in and on Practice: Lessons Learnt from a Formative Evaluation of Students' Experiences of a Technology-Enhanced Blended Learning Design." British Journal of Educational Technology 41(2): 271-86. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. 1986. Experience and Education. The Educational Forum 50(3): 241-252. [ Links ]

Dipa, K. 2020. "Covid-19 Presents Curricula Crunch for SA's Universities." https://www.iol.co.za/saturday-star/news/covid-19-presents-curricula-crunch-for-sas-universities-47191206. [ Links ]

Dominguez-Whitehead, Y. 2017. "Food and Housing Challenges: (Re)framing Exclusion in Higher Education." Journal of Education 2017(68): 150-168. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, S. 2020. "Students: Important Information for Online Learning in Term 2." http://www.sun.ac.za/english/Lists/news/DispForm.aspx?ID=7283. [ Links ]