Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Higher Education

versão On-line ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.35 no.4 Stellenbosch Set. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/35-4-4244

GENERAL ARTICLES

How university students in South Africa perceive their fathers' roles in their educational development

C. I. O. OkekeI; I. A. SalamiII

ISchool of Education Studies University of the Free State Bloemfontein, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3046-5266

IIDepartment of Early Childhood and Educational Foundations University of Ibadan Nigeria https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9788-5532

ABSTRACT

The larger study that has influenced this article was designed to explore what influenced rural men's capabilities to actively participate in children's early social development and its impact on transition to adulthood among their university-going children. Studies have established an increase in the level at which fathers in South Africa have been found wanting in terms of supporting their children's development at early stages in their lives. It has been reported that this unacceptable behaviour can be transmitted or carried over from one generation to the next. There is the belief that the majority of the young male children who experienced non-supportive fathers will grow up repeating this behaviour with their children. This calls for a study on the perceptions of young people about what fatherhood is all about, hence this study. This study used a descriptive survey with a sample size of 300 students studying education in one university in the Eastern Cape Province. A 25-item questionnaire titled Perception of Fatherhood by University Students (α = 0.75) was used to collect data that were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The participants perceived that the experience and level of education influence men's perception of fatherhood positively. Extra-curricular programmes for proper fatherhood transition of young boys are recommended, commencing from Grade 1 through to Grade 12, to expose them to the kinds of dispositions that will enable them to be responsible fathers. There is also a need for compulsory empowerment programmes such as for designers, artists and sportsmen and other semi-skilled professions for male children who cannot acquire higher education to strengthen them socio-economically to provide education for their children.

Keywords: fatherhood, fathers' responsibilities, intervention programmes, perceived fatherhood, socio-educational development, South Africa, university students

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT FOR THE STUDY

Several studies have established an increase in the levels of South African fathers not assuming their responsibilities of contributing to and supporting their children's early educational development (Chauke and Khunou 2014; Makusha and Richter 2015; Idemudia, Maepa, and Moamogwe 2016; Koketso et al. 2019). The majority of young fathers seem to prefer to abandon their responsibilities of child care, development and protection into the hands of the mothers of their child/ren (African Report 2015; Zulu 2018; Varney-Wong 2019). The majority of fathers seem limited in the support they can provide their children and families to only the provision of financial support by government. However, government cannot always afford this responsibility (Mosholi 2018; Zulu 2018). A study by Law (2019) suggested that where children are left to develop without the guiding presence of their fathers, development of such children will be negative. Studies have also reported that children who have grown up in this kind of scenario appear to replicate this behaviour with their own children (Rabe 2018; Law 2019; Varney-Wong 2019). In support, studies by Mercer (2015), Roman, Makwakwa, and Lacante (2016), and Ratele and Nduna (2018) argued that a male child who had experienced bad fathering practices might exhibit the same practices to his child/ren.

Given the above scenario, we became concerned with the knowledge that the majority of students in the faculty of education of one university in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa appeared to hold the belief that their fathers were not fulfilling their fatherly roles in their lives. The students expressed the notion that their fathers did not ensure the successful transition from their early years through to their university education. We came about this knowledge through presentations on schooling, society and inclusive education in a module offered to both bachelor of education and postgraduate certificate in education students. Though this, opportunities were presented for discussion of issues around the family. From the start of 2012, over 1300 initial teacher-training students were engaged to develop their understanding of how their family life has affected their education and career by reminiscing carefully on their early childhood care, social development and education. These students were requested to relate their early childhood experiences, in particular how fathering had impacted their educational development through to university level. Whatever their experiences had been, the students had the opportunity to explain whether their childhood experiences could have been different given different circumstances.

Although discussions around the abovementioned issues form a part of teacher preparatory programmes, it was apparent from the interactions with the students that their fathers were absent in their lives. In addition, some of the male students' discussions appeared to denote a lack of interest in the practice of guiding their children through to meaningful adulthood. Most surprisingly, some of the students actually preferred to not discuss issues pertaining to their fathers. Their discussions in the module presented revealed to us a huge research problem. Given the very strong link between family and schooling, and the fact that successful schooling experiences for the individual require family-school synergy, the feelings and expressions of these students further emphasised the imperativeness of this kind of research. From the student narratives, it was obvious that not all were right in the students' homes and with the way in which their fathers and men in their societies handled the early childhood care, social development and education of children.

From the point of view of family formation, fathering skills are loosely conceptualized in this article as the maintenance of responsibilities needed to be carried out to ensure the successful, positive growth of a child. Law (2019) reported that many South African fathers are either unable to perform these responsibilities or, where some of them do, they struggle to persist due to poverty. Notwithstanding, studies (Mosholi 2018; An and Naidoo 2019; Botha and Meyer 2019) have indicated that bad fathering skills have severe negative implications on societal development because of their direct effects on the development of male children and its replication by nature in the life of their own children when these male children themselves become fathers. A cyclical situation then prevails, where one generation of men tries to avoid and prevent the failures of their fathers; however, equally unfortunately is that their attempt at doing so with their own children becomes a generational mistake. It would seem that not enough research studies have been carried out on this phenomenon (African Report 2015).

Thus, given the context in which the abovementioned university students undertaking initial teacher training were made uncomfortable by the content of modules in which the roles of fathers were discussed, it became imperative to investigate their views on their fathers' roles in their educational development. By so doing, we argued that understanding the influences on rural men's capabilities to actively participate in children's early social development and how these influences impact on the transition of their university-going children was imperative. We hoped that such study was capable of generating useful empirical data that may support meaningful, effective and functional intervention programmes to be factored into the learning of students who would become professional teachers and parents. Also, such empirical evidence may enable adjustment programmes that would encourage individuals undertaking university education to develop parenting habits that may ensure better home and school experiences not only for their own children but also for other children alike.

Drawing from the likes of Mosholi (2018), Koketso et al. (2019) and Varney-Wong (2019), we conceptualize a father as a caregiver who identifies as male in all its diverse aspects. These include biological father, stepfather, divorced father, separated father, father in same-sex relationship or transgender father. This conceptualization also extends to include men who are actively caring for children either as foster parent or through the kinship system. Participation of a father in the home affairs might not be unconnected with the type and availability of such father at home. For instance, a father can be classified as a residential biological father who accepts the child, a residential biological father who does not accept the child or a non-residential biological father who accepts the child (Richter 2006; Mosholi 2018; Zulu 2018; Rodríguez-Ruíz, Carrasco, and Holgado-Tello 2019). Furthermore, he can also be a non-residential biological father who does not accept the child, a concerned father or mother's male relative, other concerned male relative, the mother's new husband/boyfriend, the concerned parents' friend/neighbour, or a concerned teacher (Rabe 2018; Ratele and Nduna 2018; Botha and Meyer 2019). What is important here is that as the type of father varies, so also does his level of involvement or participation in the family's responsibilities.

Whatever the type of fatherhood being practiced, the perception of fatherhood such person holds can influence his fathering skills. Richter, Chikovore, and Makusha (2010) submitted that, as at 2010, South Africa had the second highest rate of father absenteeism in Africa (second to Namibia). The authors went further to highlight that many of these fathers recognise the fact that they lack experience and guidance regarding father roles and responsibilities. Furthermore, Richter et al. (2010) noted that many of the fathers of today speak with sadness about not knowing their own individual biological fathers. This implies a few factors that may be brought into question, if not doubted. These include the beliefs and perceptions of today's South African fathers about what fatherhood is all about, recognition and respect accorded to a father, and roles and responsibilities and other fathering skills expected of a father.

IMPACT OF A FATHER ON THE FAMILY AND THE CHILDREN

In every society, a father is an important figure, not only at home, but also in the society at large (Mosholi 2018; Ratele and Nduna 2018). The impact of a father is recognised at home in childrearing when it comes to the provision of human, social and financial capital; provision and protection of the members of the family; and love and care; making a father an indispensable figure at home (Richter 2006; Madhavan et al. 2014; Botha and Meyer 2019). In the community also, fathers are those who protect and who yield security, governance, leadership and developmental power. In the precolonial era, history has it that South African fathers were respected for being the providers and protectors of not only the children and family members but also the entire community, being custodians of power and responsible adults in society (Lesejane 2006). However, the multicultural system brought about by colonialism, loss of economic power and other socially related factors have had a negative influence on the fathering skills of South African fathers (Makusha and Richter 2015).

Another strong factor working against fathering skills is cultural beliefs. For instance, Makusha and Richter (2015), Makusha, Van den Berg, and Lewaks (2018) and Zulu (2018) reported that beliefs about marriage rights, such as inhlawulo (payment of damages by a man to a woman's family for impregnating her before marriage) and lobola (bridal price), coupled with poor financial capacity, have set back many South African men in their roles and responsibilities in the family. Despite this, Madhavan et al. (2014) argued that, nowadays, fathers do provide financial support for their children, even after union dissolution, which might be because of the implementation of some family laws.

The impact of the contributions of fathers to the empowerment, sustainability and development of the family, which eventually translates to the development of the entire society, cannot be overlooked. Richter et al. (2010) opined that an involved father living at home could make a great difference. It brings about a better household; causes the mother to feel affirmed and assisted; and encourages and supports child nutrition, health care and schooling. In addition, the children enjoy and feel safe under the father's protection and benefit from his position in the community. These scholars also warned that a child considered as fatherless generates in the child a sense of loss and confusion. It has also been reported that men's positive involvement in fatherhood and caregiving can improve gender dynamics, decrease violence and improve the health and wellbeing of women, men and children (African Report 2015). All these factors point to the fact that fatherhood strengthens the quality, development and sustainability of families, which are the units of a society. In other words, a meaningful plan for the development of society should target families by ensuring supportive fathering skills for fathers. This submission must be what the South African Government recognised when promulgating a law that supports positive parenting, as presented in Chapter 8 of the Children's Amendment Act (South Africa Act No. 41 of 2007) under Section 144. The South African Act No. 41 (2007) focuses on developing the capacity of fathers to act in the best interest of their children by strengthening positive relationships within families, improving the care-giving capacity of fathers and using non-violent forms of discipline (Gould and Ward 2015).

FATHERING PRACTICES IN SOUTH AFRICA

As crucial as fatherhood is to the development of a society, fathering in South Africa, most importantly when it comes to childrearing practices, home support and participation in the socio-educational development of children, is nothing remarkable. Richter et al. (2010) reported that South Africa has the lowest marriage rate on the African continent, the second highest rate of father absenteeism, low rates of paternal maintenance for children and high rates of abuse and neglect of children by men. These are terrible statistics, and, of course, such statistics present a huge research agenda for stress researchers to investigate childhood stress that stems from inconsistencies within a family. In the same vein, Gould and Ward (2015) discovered that 50 per cent of children in South Africa grow up in households without the support of the father, while Makusha and Richter (2015) claimed that only one third of preschool children live with their father.

This lack of South African fathers' participation, support and involvement in the socio-educational development of their children and families appears to be worsening (African Report 2015; Mncanca and Okeke 2016; Mncanca, Okeke, and Fletcher 2016; Mathwasa and Okeke 2016). The adverse effects of this unacceptable societal behaviour by men are also widely reported in literature. Gould and Ward (2015) name these effects to be the likelihood of children abusing drugs and/or alcohol, engaging in risky sex and becoming involved in crime. Absent fathers have also been identified as one of the major causes of violence, spread of HIV/AIDs, school dropout and child abandonment in the society (Makusha and Richter 2015).

The impact of education on the fathering skills of South African men has not been adequately reported on in literature in an empirical and specific way. Though there are research studies on rural and Black fathers (see, for instance, Madhavan and Roy 2012; Mufutau and Okeke 2016; Mncanca et al. 2016; Koketso et al. 2019; Law 2019), which have some elements of participants being literate or otherwise, these studies have not succinctly shown if level of education can influence fathering skills or not. The level of education acquired by men and the perception they hold about fatherhood might dictate not only their fathering skills but also pinpoint the causes of poor fathering skills experienced among them. It is on this note that the perceptions of university students were sought on the influence of fathering experience and education on fatherhood, as well as responsibilities expected of a father among South African men. Again, factors that could affect the university students' perceptions, such as gender, age, race and marital status, were also explored.

AIM AND OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

The main aim of this study was to examine the perceptions of university students on fatherhood and the implications this would have for effective interventions. Specifically, the study sought to:

• Examine university students' perceptions towards the influence of fathering experience on men's knowledge of fatherhood.

• Explain university students' perceptions towards influence of education on men's knowledge of fatherhood.

• Establish university students' perceptions towards responsibilities expected of a father.

• Determine the influence of gender, age, race and marital status on university students' perceptions of fatherhood.

• Present the implications of the findings to formulate effective interventions for fatherhood in South Africa.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

From the above specific objectives, the following research questions were formulated to guide the study:

• What are the perceptions of university students on the influence of fathering experience on men's knowledge of fatherhood?

• What are the perceptions of university students on the influence of education on men's knowledge of fatherhood?

• What are the perceptions of university students on the responsibilities of a father?

• Do gender, age, race and marital status significantly influence university students' perceptions of fatherhood?

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This study examined the views of young adults on fatherhood, who at the time of the study attended one university in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. By this exploration, we intended to determine if their perceptions form part of what factors have been dictating the fathering skills of today's South African fathers. For this reason, we anchored the study on the Social Capital Theory (Coleman 1986; 1988; 1990). Coleman (1988, s98) noted that social capital comprises certain kinds of resources available to an individual that resonate through the nature of influence they exact on another significant individual/s within a specific environment/s. Coleman (1988) noted the productive nature of these resources or dispositions, and argued that the quality of human interaction is informed by either its presence or absence thereof. The function of social capital in the creation of human capital resides in the values inherent in these resources, which the individual or human actor can use to achieve their own personal interests (Coleman 1988, s101). Coleman (1988; 1990) adopted two theoretical traditions of social actions - rational theories and functionalist views. While rational theory suggests that the actor's goals are determined by a utility-maximising pursuit of his/her self-interest, the functionalist views social actions as being conditioned by social structure (see also Tzanakis 2013).

Social Capital Theory, as outlined by Coleman (1988), explains how an individual's perception is connected to his/her interest, which dictates the action put on by such individual in a particular social setting. For instance, within the family context, Coleman (1988, 109-113) highlighted the importance of the quality of interaction between parents and their children. Parental knowledge, experience, availability for parent-child interaction and the amount of time spent in the form of social capital are of the essence to Coleman in determining the quality of the created human capital. Coleman (1986; 1988; 1990) argued that parental absence in the lives of children signifies a lack of an important aspect of social capital necessary for the normal growth of such children. What this meant for Coleman (1988, 111) is that whatever human capital exists in the parents (even if parents are medical doctors, lecturers, engineers or the likes) does not exist in their children for the simple fact that social capital is missing. Thus, despite the quality of human capital parents possess by virtue of their training and professional standing in society, such professional and personality dispositions may become irrelevant for their children if they are not present in their lives.

Researchers have adopted Coleman's Social Capital Theory in their efforts at explaining its impact in the developmental trajectory of children. For instance, Lo Yu et al. (2019) applied the theory in their study to explore how family social capital in late childhood can predict youthful drinking behaviours and problems. They found that by monitoring children's daily activities, parents may most likely lower their children's engagement in alcohol-involved activities and this will help such parents to reinforce some pro-social norms and behaviours in their children timeously (Lo Yu et al. 2019, 6). Similarly, An and Western (2019) explored the link between family social capital and children's participation in extracurricular activities and hypothesised that teenagers from more comfortable families are more likely to participate in organised extracurricular activities. The authors also hypothesised that children living with a single parent or cohabiting (unmarried) couple are less likely to participate in organised extracurricular activities than those who live with a married couple (An and Western 2019, 194-195). They found that family structure in the form of social capital matters for extracurricular-activity participation by children. Children in married, two-parent families are more involved in organised extracurricular activities than those in single-parent or cohabiting-couple families (An and Western 2019, 202). In addition, Hunter et al. (2019, 549) explored the influence of kinship- and community-based social capital, comprising intergenerational closure on children's social competences, among South African American families. They found that families and community-based social capital have the potential to bind children together with each other and this enables the creation of the necessary social cohesion that engender good neighbourly behaviour among children and their families (Hunter et al. 2019, 555).

A family's social capital entails the quality of relationships between parents and their children. This is germane for understanding how the university students who took part in this study perceived their relationships with their fathers and how these translate to their individual experiences of their fathers' contributions to their educational development. Coleman's Social Capital Theory thus presented us with the fitting tool to understand why most of the categories of university students participating in this study felt uncomfortable by the mention of their fathers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A descriptive-survey research design was adopted to carry out this study. Descriptive-survey research is a research design focusing on the collection of existing data through questionnaires and analysing the data and describing the situation as it is (Ary, Jacobs, and Sorensen 2010; Creswell 2014). The target population of the study was the Faculty of Education students of the School of General and Continuing Education (SGCE), East London Campus, of the University of Fort Hare in the Eastern Cape. A sample comprising of 300 students was randomly selected.

According to gender distribution, the sample comprised of 43 per cent male students and 57 per cent female students. Race distribution was as follows: Black students 78 per cent, White students 13 per cent, Coloured students 7 per cent and Indian students 2 per cent. Age distribution of the sample shows that 50 per cent of the sample was aged between 18 and 25; 20 per cent between 26 to 30; 16 per cent between 31 to 35 and 14 per cent above 35 years of age. Concerning marital status, 20 per cent of participants were married, 69 per cent were single and 11 per cent were divorced.

A self-designed questionnaire, titled Perceptions on Fatherhood (α = 0.75), with four sections was used to collect data. Section A measured the demographic information of the participants. Section B had nine items which measured participants' perception about the influence of fathering experience on fatherhood practices. Section C had 10 items which measured participants' perceptions about the influence of education on fatherhood practices. Lastly, Section D had six items and measured the perception of the participants about the responsibilities of a father. The data collected were analysed using both descriptive and inferential statistics and the significance level was tested at 0.05 level.

ISSUES OF ETHICS

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the university where the researchers worked resided at the time of the study. Further clearance was also obtained from the metropolitan municipality in which the university that participated in the study was located. We clearly explained the purpose of the study to the prospective participating students. We also explained that participation in the study was voluntary. Subsequently, they signed informed consent forms. Participants were assured of unlikely injury or any form of discomfort on their persons. We kept in mind the context preceding the study. As a result, we made adequate arrangements in this regard. We assured the participants of their right to withdraw their participation from the study whenever they felt uncomfortable. We also had referral forms available to refer such participants to professional counsellors should the need have arisen. Lastly, participants were advised not to hesitate to contact any of the researchers should the need have arisen to reach us.

RESULTS

This section discusses the results according to each of the four research questions. Each research question is posed again, with the respective table depicting the data related to that question. Table 1 depicts the mean and standard deviation scores for the related questionnaire items.

Research question 1: What are the perceptions of university students on the influence of fathering experience on men's knowledge of fatherhood?

Table 1 reveals that the participants have positive perceptions that fathering experience had influence on men's knowledge of fatherhood. For instance, participants perceived fatherhood from a number of perspectives. These include what they learnt from their fathers (item 1; mean = 3.77); that male students learn about fatherhood from how men behave in the community (item 2; mean = 4.05); and that students learnt from their fathers' mistakes (item 7; mean = 3.89). In addition, participants also learnt from their fathers' parenting skills (item 8; mean = 3.64) and that male students will become better fathers if they themselves had good fathers (item 9; mean = 3.68). The weighted average of the means of the items is 3.49, which is an indication that the participants' perceptions are positive. The perceptions can be rated up to 69 per cent.

Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation scores for the questionnaire items on the second research question.

Research question 2: What are the perceptions of university students on the influence of education on men's knowledge of fatherhood?

Table 2 shows that the participants have positive perceptions about the influence of education on men's perception of fatherhood. For instance, the participants perceived that university students' parenting skills will be different because of their education (item 1; mean = 3.88); and they have more understanding and open-mindedness and are informed about positive fatherhood (item 2; mean = 3.90). Participants also believed that male students will be more disciplined fathers because of their education (item 3; mean = 3.50); university students will take care of their children, even without a job (item 4; mean = 3.54); and that it is likely that male students may delay becoming fathers until they are ready to do so (item 5; mean = 3.63). Furthermore, participants felt that university students do not have to raise their children the same way they were raised (item 6; mean = 3.79); that education is very important for male students to learn positive fathering behaviour (item 9; mean = 4.09); and that a good education and a good job will support positive fathering in men (item 10; mean = 4.10). The weighted average of the means of the items is 3.72, which is an indicator of positive perceptions. The perceptions can be rated up to 74 per cent.

Table 3 shows the mean and standard deviation scores for the questionnaire items on the third research question.

Research question 3: What are the perceptions of university students on the responsibilities of a father?

Table 3 reveals that the participants have positive perceptions about the responsibilities of a father. For instance, they perceived that they do not want to have children if they will abandon them (item 1; mean = 3.92); that one can only be a father if he is ready to live responsibly (item 2; mean = 3.87); and that positive parenting styles should be the priority of all fathers (item 4; mean = 4.33). Participants also felt that putting family first is a good sign of positive fatherhood (item 5; mean = 4.27) and that spending more time at home with the family will help develop positive fatherhood (item 6; mean = 4.19). The weighted average of the means of the items is 3.88, which indicates positive perception. The perception can be rated up to 78 per cent.

For the fourth research question, data are divided into the four categories indicated in the questions - gender, age, race and marital status.

Research question 4: Do gender, age, race and marital status significantly influence university students' perceptions of fatherhood?

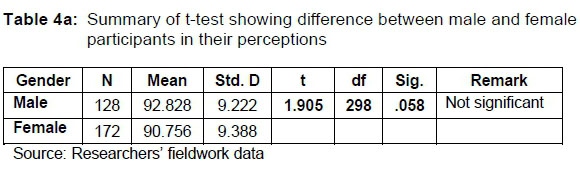

Table 4a shows the statistical scores for whether participants' gender significantly influenced their perceptions of fatherhood.

Table 4a shows that there is no significant difference between male and female participants in their perceptions (t = 1.91; df = 298; p > 0.05). This implies that gender has no significant influence on university students' perceptions of fatherhood.

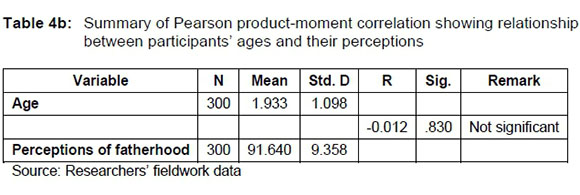

Table 4b shows the statistical scores for whether participants' ages significantly influenced perceptions of fatherhood.

Table 4b shows that there is no significant relationship between university students' age and their perceptions of fatherhood (r = -0.01; p > 0.05). This implies that age has no significant influence on university students' perceptions of fatherhood.

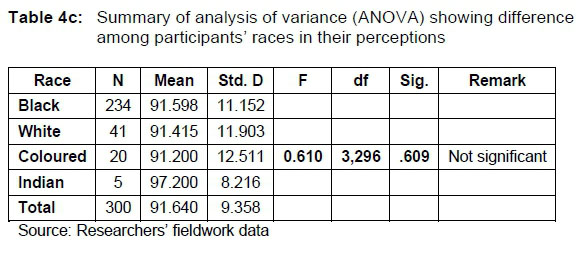

Table 4c shows the statistical scores for whether participants' race significantly influenced perceptions of fatherhood.

Table 4c reveals that there is no significant difference among the races of the participants in their perceptions of fatherhood (F(3,269) = 0.61; p > 0.05). This suggests that race has no significant influence on university students' perceptions of fatherhood.

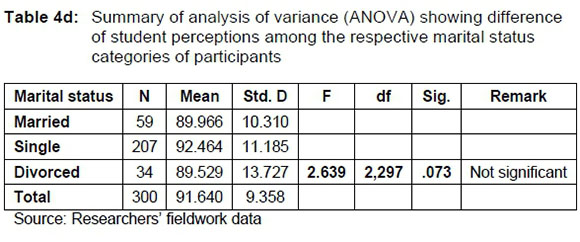

Table 4d shows the statistical scores for whether participants' marital status significantly influenced perceptions of fatherhood.

Table 4d reveals that there is no significant difference among participants with various marital statuses in their perceptions of fatherhood (F(2,297) = 2.64; p > 0.05). This suggests that marital status has no significant influence on university students' perceptions of fatherhood.

DISCUSSION

This study firstly determined that the perceptions of participating university students were that fathering experiences had by male children could influence their perception of fatherhood. This finding should not be jettisoned because it could be as a result of the experiences the participants had had of themselves or those acquired in their communities, since they are citizens of South Africa. As the saying goes - experience is the best teacher - whatever we experience directly or happens to others could affect us in one way or the other, as well as our actions. It should be noticed that if a child is exposed to bad fathering while growing up, even if the child knows that the behaviours are bad, he might not know how to go about making it better. This supports the submission of Mufutau and Okeke (2016), Makusha et al. (2018) and Koketso et al. (2019), who argued that men who experienced bad fathering while growing up will exhibit the same fatherhood too. In concurrence, Richter (2006), Gould and Ward (2015), Mathwasa and Okeke (2016) and An and Naidoo (2019) have showed that fathering style experienced by a male child could influence how he behaves in his own moral and fathering behaviour going forward.

The second finding of this study is that participating university students had positive perceptions about the influence of education on men's perception of fatherhood. Two major reasons might have accounted for this finding. First, the perception of the participants might be based on their experience as students of education programmes at university and who have thus been exposed to the benefits of quality education as capable of transforming its recipients. This is in line with Salami (2014), who argued that education is the only instrument that can be used to correct societal malice effectively. Besides this, the university environment is a rich environment where people from various family backgrounds congregate and are able to see the contributions of fathers in the lives of those students who have supporting fathers. This experience might convince any university student to want to be a responsible father. The second reason is that the perceptions of the university students might be as a result of their experiences of how well-educated South African fathers, such as their male university staff and male colleagues, exhibit good fathering skills. There are some expected dos and don'ts for educated people and these, most of the time, control their actions, not only in the family, but also in the society at large. The beliefs that these participants have on the power of the transformation education has are in line with the wise words of President Mandela, as cited by Mathwasa and Okeke (2016), that education is a vehicle that can break the cycle of poverty.

The third finding shows that the participating university students had positive perceptions about the responsibilities of fatherhood. This might be because many of the participants have been students with children also who had experienced what parenting entails. Besides this, their exposure to education and experience gained while interacting with educated people might have informed them on what the expected contributions of fathers are and the benefits associated with such. Unlike uneducated people, university students are aware that a father's involvement in the lives of his child/ren and family cannot be measured by hands-on care alone but by human, social, financial and protection supports. This is in line with the submission of Richter (2006) and Madhavan et al. (2014), that fathers' participation in the development of their children is not in hands-on care alone and that up to the present age, even after the union between father and mother has been dissolved, fathers provide financial support for the development of their children.

The last finding shows that gender, age, race and marital status had no significant influence on the participating university students' perceptions of fatherhood. In other words, the perceptions of the participants are not biased based on gender, age, race or marital status. This might be attributed to the exposure of the participants through education and social interactions. This finding corroborates the findings of Roman et al. (2016) that gender has no significant main effect and gender and ethnicity have no significant interactional effect on perceptions of parenting styles in South Africa. Therefore, the findings of this study should not be discarded.

IMPLICATIONS OF FINDINGS FOR INTERVENTIONS

The rationale behind this study was to determine how today's youths perceive fatherhood. From this research, the causes of father absenteeism in family affairs and support for their children could be discovered and effective interventions can thus be suggested. It is on this note that the implications of the findings are hereby pointed out.

It is now known that educated youths in South Africa perceive that fathering experiences had by a male child could affect his perception of fatherhood. This has two crucial implications for the interventions on fatherhood in the country. The first is that, whatever intervention is designed to ameliorate this problem must keep abreast of the fact that fathering skills can be easily transmitted from one generation to the next. Hence, strategies to ensure that today's male children have positive fathering skills should be built into such intervention. The second implication is that there should be several interventions towards exposing today's male children to positive fathering skills.

The South African Government has done a lot to ensure quality education for all children. In addition to this, however, now that we know that education can influence male-child perceptions of fatherhood positively, there should be additional efforts to ensure that male children in South Africa acquire quality education up to higher levels. This will influence the lives of the male children in two ways - exposing them to be responsible fathers, and creating opportunities for good jobs that can support them and their families.

It has also been revealed that university students, irrespective of their family background, have positive perceptions of the responsibilities of a father. This is not the case with uneducated people, which emphasises the need for compulsory higher education for male children in South Africa.

Finally, since perceptions of university students are not biased based on gender, age, race or marital status implies that what university students perceive about fatherhood cannot be attributed to biasness. The submissions are therefore devoid of any form of sentiment and, if any intervention is planned based on these findings, the probability of success of such an intervention is high.

CONCLUSION

This study sought determine the perceptions of South African university students on fatherhood through a quantitative research approach. The participants perceived that the fathering experience had by a male child can influence such children's perception of fatherhood and their fathering skills. In addition, participants perceived that education can influence the perception of a male child about fatherhood and they had positive perceptions about the responsibilities of a father. With this information, effective interventions can be suggested for making meaningful changes now and in the near future in the fathering skills of South African men.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the findings of this study, and the implications of the findings for interventions identified so far, some recommendations are proffered. The aim with these is to make many South African fathers participate in their family responsibilities, especially in terms of how it affects childrearing practices.

Firstly, there is a need to introduce a programme for male children in schools, starting from Grade 1 through to Grade 12, which will expose them to what it takes to be a man and a father. This programme should be made compulsory for all male children, but in order not to be an additional burden, such a programme could take on the form of extra-curricular activities such as a boys' club, boys' afterschool meetings or any other non-academic programme. The belief is that some lost fathering experiences could be recreated into the lives of these boys.

Secondly, there is a need for governmental and non-governmental organisations and other stakeholders in education in South Africa to be thinking towards how to ensure compulsory education to all male children up to tertiary-institution level. To encourage this, incentives in different forms can be introduced to encourage male-child education beyond secondary/high school level. Since large organisations such as the World Bank, UNICEF, UNESCO and other global organisations support girl-child science education, these organisations could be attracted to further male-child higher education for all male children.

Finally, since it is certain that some male children might not have what it takes to attend higher institutions in terms of intellectual capacity, a compulsory arrangement should be made for such children to acquire professional skills. These could include skills in designing, arts, sports and other semi-skilled professions. The arrangement should include facilities to support anyone who completes the training and would like to have his own establishment. Important to remember here is that giving training to someone without assisting such a person to start working is a job half done.

REFERENCES

African Report. 2015. State of Africa's Father. Washington DC, USA: A Mencare Advocacy Publication. [ Links ]

An, Sera and Kammila Naidoo. 2019. "Parental Involvement and the Academic Achievement of South Korean High School Students." Journal of Family Diversity in Education 3(3): 62-87. [ Links ]

An, Weihua and Bruce Western. 2019. "Social Capital in the Creation of Cultural Capital: Family Structure, Neighborhood Cohesion, and Extracurricular Participation." Social Science Research 81:192-208. [ Links ]

Ary, Donald, Lucy Cheser Jacobs, and Chris Sorensen. 2010. Introduction to Research in Education. Wadsworth USA: Cengage Learning. [ Links ]

Botha, Lettie and Lukas Meyer. 2019. "The Possible Impact of an Absent Father on a Child's Development - A Teacher's Perspective." Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe Jaargang 59(1): 54-68. [ Links ]

Chauke, Polite and Grace Khunou. 2014. "Shaming Fathers into Providers: Child Support and Fatherhood in South African Media." The Open Family Studies Journal 6(1): 18-23. [ Links ]

Coleman, James S. 1986. "Social Theory, Social Research, and a Theory of Action." The American Journal of Sociology 91(6): 1309-1344. [ Links ]

Coleman, James S. 1988. "Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital." American Journal of Sociology 94: s95-s120. [ Links ]

Coleman, James S. 1990. Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Creswell, John W. 2014. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. New York: Sage. [ Links ]

Gould, Chandra and Catherine L. Ward. 2015. Positive Parenting in South Africa: Why Supporting Families is Key to Development and Violence Prevention. Pretoria, South Africa: Institute for Security Studies. [ Links ]

Hunter, Andrea, Selma Chipenda-Dansokho, Shuntay Tarver, Melvin Herring, and Anne Fletcher. 2019. "Social Capital, Parenting, and African American Families." Journal of Child and Family Studies 28: 547-559. [ Links ]

Idemudia, Erhabor Sunday, Mokoena Maepa, and Keatlaretse Moamogwe. 2016. "Dynamics of Gender, Age, Father Involvement and Adolescents' Self-harm and Risk-taking Behaviour in South Africa." Gender and Behaviour 14(1): 6846-6859. [ Links ]

Koketso, Matlakala Frans, Makhubele Jabulani Calvin, Sekgale Israel Lehlokwe, and Prudence Mafa. 2019. "Perspectives of Single Mothers on the Socio-emotional and Economic Influence of 'Absent Fathers' in Child's Life: A Case Study of Rural Community in South Africa." Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 16(4): 1 -12. [ Links ]

Law, Lois. 2019. "The Challenges of Fatherhood in Contemporary South Africa." Briefing Paper 474:1 -5. [ Links ]

Lesejane, Desmond. 2006. "Fatherhood from an African Cultural Perspective." In Baba: Men and Fatherhood in South Africa, ed. Linda Richter and Morrell Robert, 173-181. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Lo Yu, Wan-Ting Chen, I-An Wang, Chieh-Yu Liu, Wei J. Chen, and Chuan-Yu Chen. 2019. "Family and School Social Capitals in Late Childhood Predict Youthful Drinking Behaviors and Problems." Drug and Alcohol Dependence 204: 1-8. [ Links ]

Madhavan, Sangeetha, and Kevin Roy. 2012. "Securing Fatherhood through Kin Work: A Comparison of Black Low Income Fathers and Families in South Africa and the U.S." Journal of Family Issues 33(6): 801-822. [ Links ]

Madhavan, Sangeetha, Linda Richter, Shane Norris, and Victoria Hosegood. 2014. "Fathers' Financial Support of Children in a Low Income Community in South Africa." Journal of Family and Economic Issues 35: 452-463. [ Links ]

Makusha, Tawanda and Linda Richter. 2015. "Non-resident Black Father in South Africa." In Father -Paternity, ed. J. L. Roopnarine, 30-33. Syracuse, USA: UNICEF. [ Links ]

Makusha, Tawanda, Wessel van den Berg, and Andre Lewaks. 2018. "Conclusions." In State of South Africa's Fathers, ed. Sonke Gender Justice, Human Science Research Council, 70-74. Cape Town: Human Science Research Council. [ Links ]

Mathwasa, Joyce and Chinedu Ifedi Okeke. 2016. "Barriers Educators Face in Involving Fathers in the Education of Their Children at the Foundation Phase." Journal of Social Science 46(3): 229-240. [ Links ]

Mercer, Gareth D. 2015. "Do father care? Measuring mothers' and fathers' perceptions of fathers' involvement in caring for young children in South Africa." Unpublished doctoral thesis. Vancouver, Canada: The University of British Columbia. [ Links ]

Mncanca, Mzoli and Chinedu Ifedi Okeke. 2016. "Positive Fatherhood: A Key Synergy for Functional Early Childhood Education in South Africa." Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 7(4): 221-232. [ Links ]

Mncanca Mzoli, Chinedu Ifedi Okeke, and Richard Fletcher. 2016. "Black Fathers' Participation in Early Childhood Development in South Africa: What Do We Know?" Journal of Social Science 46(3): 202-213. [ Links ]

Mosholi, Mpotseng Sina. 2018. "The lived experiences of resilient Black African men who grew up in absent-father homes." Unpublished master's dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Mufutau, Monsuru Atanda and Chinedu Ifedi Okeke. 2016. "Factors Affecting Rural Men's Participation in Children's Preschool in One Rural Education District in Eastern Cape Province." Studies on Tribes and Tribals 14(1): 18-28. [ Links ]

Rabe, Marlize 2018. "A Historical Overview of Fatherhood in South Africa." In State of South Africa's Fathers, ed. Sonke Gender Justice, Human Science Research Council, 10-26. Cape Town: Human Science Research Council. [ Links ]

Ratele, Kopano and Mzikazi Nduna. 2018. "An Overview of Fatherhood in South Africa." In State of South Africa's Fathers, ed. by Sonke Gender Justice, Human Science Research Council, 27-46. Cape Town: Human Science Research Council. [ Links ]

Richter, Linda. 2006. "The Importance of Fathering for Children." In Baba: Men and Fatherhood in South Africa, ed. Linda Richter and Morrell Robert, 53-61. Cape Town, South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Richter Linda, Jeremiah Chikovore, and Tawanda Makusha. 2010. "The Status of Fatherhood and Fathering in South Africa." Childhood Education 86(6): 360-365. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Ruíz, Maria Mercedes, Miguel Á. Carrasco, and Francisco Pablo Holgado-Tello. 2019. "Father Involvement and Children's Psychological Adjustment: Maternal and Paternal Acceptance as Mediators." Journal of Family Studies 25(2): 151-169. [ Links ]

Roman, Nicolette Vanessa, Thembakazi Makwakwa, and Marlies Lacante. 2016. "Perceptions of Parenting Styles in South Africa: The Effect of Gender and Ethnicity." Cogent Psychology 3(1): 1 -12. [ Links ]

Salami, Ishola A. 2014. "Attempt at reforming education and the challenge of national liberation in Nigeria: The place of early childhood education." Presented at the Educational Summit organised by Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) held in Abuja, Nigeria, 27-31 October. [ Links ]

South Africa. 2007. Children's Amendment Act (Act No. 41 of 2007). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Tzanakis, Michael. 2013. "Social Capital in Bourdieu's, Coleman's and Putnam's Theory: Empirical Evidence and Emergent Measurement Issues." Educate 13(2): 2-23. [ Links ]

Varney-Wong, Anna M. 2019. "An exploratory study of the influence of an absent father on the identity formation of women." Unpublished master's dissertation. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Zulu, Ncamisile Thumile. 2018. Resilience in Black Women Who do not Have Fathers: A Qualitative Inquiry. South African Journal of Psychology 49(2): 219-228. [ Links ]