Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Higher Education

versión On-line ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.34 no.4 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/34-4-3627

GENERAL ARTICLES

Trainee accountants' perceptions of the usefulness of the business ethics curriculum: a case of SAICA in South Africa

K. N. MasekoI; A. MasinireII

IDepartment of Accounting, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. e-mail: ksema0018@gmail.com / https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7640-9580

IICurriculum Studies, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. e-mail: Alfred.Masinire@wits.ac.za / https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1329-8569

ABSTRACT

The main research objective of this study was to determine whether Chartered Accountancy (CA) trainees consider business ethics education they received to be useful, and to investigate if it was given the necessary attention at SAICA-accredited universities. The data obtained from CA trainees using a survey was analysed using four theoretical constructs, namely: a) Adequacy of coverage of ethics education, b) Importance of ethics, c) Impact of ethics education on ethical awareness and, d) Effectiveness of ethics education. Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests of normality were applied to the theoretical constructs to determine if the data was normally distributed. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine if there were significant differences when opinions were categorized according to gender, study mode (part-time or full-time) and highest academic qualification. The Cronbach alpha coefficient was computed to test the reliability of participants' responses to the survey. The study has found strong agreement among CA trainees that business ethics education is receiving adequate attention at SAICA-accredited universities and is useful in both their professional and personal lives.

Keywords: business ethics curriculum, SAICA, higher education, South Africa

THE PROFESSIONAL AND CURRICULUM CONTEXT OF BUSINESS ETHICS

South Africa is presently reeling from the ethically questionable conduct of KPMG audit firm whose forensic report on the so-called "rogue unit" within South African Revenue Service (SARS) laid the foundation for the removal of the then finance minister, Pravin Gordan (Joffe 2017). This precipitated and amplified political turmoil, and caused significant economic damage to the country. The rand depreciated, wiping about R86 billion off South African (SA) banks' market capitalization (Laing 2017). KPMG acknowledged later that its leadership had shown very poor judgement. Following the KPMG scandal, the South African accounting profession lost its previously awarded World Economic Forum (WEF) top ranking for the rigour of its audit and adherence to reporting standards (Laing 2017). It is now ranked number 31. However, the losses associated with this KPMG episode pale in comparison with the almost R300 billion lost by investors consequent to the Steinhoff accounting scandals (Cairns 2017). This has raised questions around the ethical conduct of Steinhoffs auditor, Deloitte SA, which is presently being investigated by the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (IRBA).

The events mentioned above continue to inflict reputational damage on the accounting profession in SA, and have resulted in the loss of its once global prestige, as shown in the latest WEF rankings. The prime reason the accounting profession exists is that its financial reports are relied upon by various stakeholders when making economic decisions. The international accounting conceptual framework states that the purpose of financial reporting is to provide investors, lenders and other creditors with information that will enable them to make decisions about providing resources to the entity (International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) 2016, 2). Thus, auditors, most of whom use the Chartered Accountant (CA) designation, evaluate their clients' financial statements to provide independent assurance regarding the fairness of their presentation (IAASB 2017, 82). However, the recent ethically questionable conduct of these two "big four" accounting firms (KPMG and Deloitte) puts into doubt the integrity of and/or the need for the privileged status of the accounting profession.

While South Africa's accounting profession faces these fundamental ethical challenges, globally there are also concerns arising from the apparent moral degradation of professional accountants. It was the demise of Arthur Anderson in 2001, a former "big 5" audit firm, which amplified the emphasis on business ethics education in SA and across the globe. The audit failures at the heart of the Enron and Worldcom corporate scandals underscored a need for the integration of ethics into the accounting curriculum (Haas 2005, 66), reaffirming earlier concerns that business ethics education was receiving at best superficial and peripheral academic coverage (Cohen and Pant 1989; McNair and Milam 1993; Loeb and Bedingfield 1972). Another common finding was that business ethics were receiving coverage primarily in auditing courses which focused on testing knowledge of Code of Professional Conduct (CPC) developed by accounting bodies (Cohen and Pant 1989; McNair and Milam 1993; Loeb and Bedingfield 1972; Gunz and McCutcheon 1998). This study explores the usefulness and value of the business ethics curriculum for chartered accountants in the light of above ethical concerns.

In SA, The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA) developed a competency framework in 2008 which, inter alia, sought to address the narrow focus of ethics education on CPC. Updates were made to the SAICA competency framework in 2010, 2014 and 2016. It offers universities two curriculum options regarding business ethics education. The first is to offer two half-semester modules of six weeks each and the second is a full 12-week semester course (SAICA 2014, 161-163). Thus, aspiring Chartered Accountants (CAs) are presented with three months of ethics-focused education during their formal academic training. However, as SA continues to reel from the enormous scale of the so-called "state capture" phenomenon, and the alleged involvement of KPMG in aiding state capture, the ethical conduct of the accounting profession in SA has been brought into question. This creates doubts regarding the effectiveness of ethics education offered by SAICA-accredited universities.

The Cohen Commission (1978) reported that the ability of a learned profession to fulfil its responsibilities is inextricably linked to the strength of its educational base. The resurgence of ethical lapses of professional accountants may be indicative of deficiencies in aspects of accounting curricula at the SAICA-accredited universities and also globally. It was worth investigating whether the broader focus given to business ethics education that goes beyond mere knowledge of CPC in the SAICA's 2014 competency framework is being executed by SAICA-accredited universities. Another consideration is that ethics education at university level may not effectively modify a person's ethical sensitivity. Also, mere moral vigilance does not suffice. The value of ethics education is in its ability to improve a person's moral judgment. SA is presently dealing with the economic consequences of bad decisions that were taken, among others, by some senior accounting professionals. Good ethical judgment, resolutely applied, would thus be the ultimate prize. This study therefore sought to obtain the perceptions of South African CA trainees on the following research questions:

1. Do CA trainees perceive ethics education at institutions of higher learning to be adequate?

2. Do CA trainees believe ethics education at universities improved their ethical sensitivity?

3. Do CA trainees believe ethics education at institutions of higher learning improved their ethical judgment?

In summary: the main research objective of this study was to determine whether CA trainees consider the ethics education they received to be useful, and if it was given the necessary attention at SAICA-accredited universities.

RATIONALE AND SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY

The issue of the ethical preparedness of many new accountants begs the question of whether the business ethics curriculum offered in tertiary institutions adequately prepared them for the responsibilities they faced after graduating. In SA currently, SAICA expects students to have an advanced knowledge of business ethics. This means that upon entering the accounting profession, CAs in SA should already be equipped with knowledge of ethics sufficient to enable them to meet the expectations of their employers and clients. Obtaining the perceptions of CA trainees, who are undergoing practical training is one way of ascertaining the strength and pertinence of their ethics education. The fact that ethics are assessed at the highest undergraduate and immediate post-graduate levels at SAICA-accredited institutions of higher learning shows the significance attached to business ethics by the professional body. It would therefore benefit SAICA if it could obtain feedback on how CA trainees perceive the usefulness of their ethics education in helping them identify and evaluate ethical problems encountered in the workplace.

CONCEPTUALIZING THE USEFULNESS OF BUSINESS ETHICS CURRICULUM KNOWLEDGE

There are controversies among curriculum scholars about what should constitute curriculum content (Luke, Woods and Weir 2013, 9). There are two perspectives from which these controversies are conducted, namely the socialist and the asocial perspectives (Moore 2000, 20). Asocial perspectives embrace logical positivism and progressivism, while social realist views include neo-conservatism, technical instrumentalism and post-modernism (Moore 2000, 19-20).

The asocial curriculum perspective

Positivism and progressivism are the two dominant philosophies driving asocial curriculum views. Positivism, claiming that empiricism should undergird knowledge (Moore 2000, 20), is premised on behaviourism, which gave rise to behavioural objectives and the objective style of assessment (Dearden 1981 37). Any knowledge not congruent with the parameters of science (i.e., theory and sense experience) was derided and ultimately trivialized. Consequently, preeminence in science became a source of rational Western positivist epistemology (Pinar 2007, 2). Positivism thus effectively disconnected society from knowledge in its efforts to remove any social distortions of "pure" knowledge (Moore 2000, 20).

One of the distinguishing characteristics of positivism is its rejection of moral, social and political education (Dearden 1981, 37). In the United States (US), the events of 11 September 2001 prompted nostalgic introspection that brought with it the realization that a solely empirical curriculum is inadequate as it is unable to contribute meaningfully to matters such as social coherence (Pinar 2007, 21). Positivism's view of the child's mind as a tabula rasa, ready to absorb empirical knowledge, did not go unchallenged (Darling-Hammond 1998, 644). The challenge came from progressivism, another asocial view of the curriculum.

While positivism attempts to get society out of knowledge, progressivism wants to get society out of the child (Moore 2000, 20). Unlike the positivist conception of a child as a "blank canvas", progressivism is premised on Piagetian cognitive-developmental psychological theory which perceives the child to be born with mental schemas (Kohlberg and Mayer 1972, 450). These mental schemas develop as the child interacts with the environment and therefore the goal of education should be to propel human beings to the highest stage of development through their interactions with suitably structured learning environments (Kohlberg and Mayer 1972, 454). Knowledge therefore derives from the equilibrium between the interactions of an inquisitive human participant and the educational environment's problematic scenarios (Kohlberg and Mayer 1972, 455). The curriculum is thus student-centred, focusing on problem solving activities (Ornstein 1990, 107).

Moore (2000) points out that positivism ceased to have a major influence in epistemology and the philosophy of science in the 1930s. Both progressivism and positivism are deemed inadequate because knowledge is now better understood to be inherently social (Moore 2000, 20). For instance, scientific procedures have historical evolution which gives them a social dimension. Knowledge is thus an embodiment of history and experience (Young 2007, 8). The view of knowledge as inherently social aligns with the social realist curriculum perspectives, namely: neo-conservatism, technical-instrumentalism, and post-modernism.

Social realist curriculum views

Neo-conservatism regards the curriculum as a given body of knowledge which the school is responsible to transmit (Young 2007, 19). The school is therefore deemed effective when it can maintain tight control over curriculum, teaching and students (Apple 2004, 17). The result is a curriculum that fosters discipline and proper respect for authority (Young 2007, 20). The implication of this view is that the subjects offered in the neo-conservative curriculum should encourage loyalty to society's cultural heritage. When there is a decline in educational success and morality, conservatives are swift to attribute such decline to departures from "canonical texts". Neo-conservatism is criticised for its ignorance of epistemological concerns and the dynamism of society (Moore and Young 2001, 447). To ensure proper alignment between the changing needs of society and the curriculum, the technical-instrumentalism curriculum perspective was conceived.

Technical-instrumentalism holds that the curriculum should serve the economic needs of society and ensure the future employability of the students (Moore and Young 2001, 450). However, as the economy is dynamic, this view requires the curriculum to adapt to the changes in the economy. A curriculum is then a means to ensure learners are prepared for the globalised and knowledge-based economy and is not an educational end in itself (Young 2007, 20). A counter-argument against instrumentalism is that no research evidence yet corroborates causality between curriculum and economic indicators, as some countries continue to have good education systems despite plummeting economic indicators - such as Zimbabwe (Moore 2000, 23). This view also renders the curriculum vulnerable to the whims of politicians who may use it as a scapegoat to cover their mismanagement of the economy. When politicians assume curriculum control, de-professionalization of teachers occurs (Luke et al. 2013, 4).

The concern regarding the potential of technical-instrumentalism to vest curriculum control in the hands of those wielding political and economic power has been voiced by postmodernists. Post-modernists consider themselves advocates for the marginalized in society and view the curriculum as a tool of liberation for the oppressed (Moore 2000, 20). The struggle for recognitive and redistributive justice requires the curriculum to be inclusive (Frazer 1997, as cited in Luke et al. 2013, 4). Recognitive justice is achieved through the recognition of the knowledge and cultural heritage of the oppressed in the curriculum, while redistributive justice advocates for a curriculum that would help the disenfranchised gain access to material wealth and opportunities to participate in mainstream economic and civic life (Luke et al. 2013, 4). Postmodernism is obsessed with the deconstruction of elitist curricula and thus lays itself open to criticism for not proposing realistic alternative curriculum options, and for viewing other curriculums as devoid of even an element of truth (Moore and Young 2001, 449).

This polarization of curriculum views above leaves us in an epistemological and educational dilemma (Alexander 1995, in Moore and Young 2001) which we can only escape through understanding the social reality and attributes of knowledge which reconciles aspects of asocial curriculums with social curriculum notions. Social realist view knowledge as intrinsically social because the construction of truth always involves a dialogue with others (Moore and Young 2001, 458). This position counters the asocial views of positivism and progressivism. With social realism, the social character of knowledge is considered indispensable to its objectivity (Moore and Young 2001, 450). This is because the social construction of knowledge occurs within specific collective codes and values (Moore and Young 2001, 458). The codes and values become standards by which knowledge's objectivity can be assured. Respect for social codes and values in the construction of knowledge should thus accord with neo-conservatism, while simultaneously countering technical-instrumentalism's preference for meddling or "making adjustments". Regarding the increasingly recognised presence of inequality (which post-modernists struggle against), Moore and Young (2001, 458) propose a widening of internal or cognitive interests' participation, rather than external interests, because external interests ignore the subject of knowledge. As this research project is about the accounting curriculum in South Africa, it is appropriate to reflect on where accounting is located within the curriculum discourse.

The business ethics curriculum

In SA, the accounting curriculum is determined by the SAICA. All universities offering undergraduate and post-graduate qualifications for students aspiring to become CAs must ensure their programmes are SAICA-accredited. Prior to 2010, the SA accounting curriculum was theory-based, exhibiting a neo-conservatism curriculum stance (SAICA 2014, 4). It now follows a competency-based model which identifies and describes knowledge, skills and attributes that a CA should be able to demonstrate when they enter the profession (SAICA 2014, 4). A competency-based model retains a neo-conservative status by maintaining theory as its centrepiece, but adopts a technical instrumentalist dimension by incorporating skills and attributes that students should be able to demonstrate when they join the working fraternity.

The SAICA competency framework is not only applicable to education programmes at the universities. It also extends to the CA trainees' on-the-job training. It derives its philosophy from the American pragmatist philosopher, John Dewey. Dewey's view is that there is an intimate and necessary relationship between education and actual experiences (Ansbacher 1998, 38). SAICA believes that knowledge is easier and more interesting to learn if it links with student's personal experiences and/or current issues (SAICA 2014, 12). The aim is to produce a responsible professional that SAICA describes as someone who is able to integrate technical knowledge with pervasive qualities and skills, the latter including a "good moral ethos" (SAICA 2014, 9).

In the light of the many recent corporate scandals implicating professional accountants, the expectation was that business ethics education would be more enthusiastically adopted and would enjoy more prominence in the accounting curriculum. In the SA context, the strong emphasis on ethics in the SAICA curriculum means that ethics education at universities receives significant attention. The question is whether higher learning institutions are the appropriate channels (have the appropriate skills and intentions) for laying a good ethical foundation for future professional accountants. Against this background, Bernardi (2004, 145) observes that ethics are a secondary interest for academics in both teaching and research. A study by Hoffman and Moore (1982, 81) found that only 317 out of a total of 1200 colleges and universities confirmed they offered a social responsibility and/or business ethics course. Several arguments have been made as to why educational institutions should not be relied upon to provide business ethics education.

One of the reasons why business ethics are not taught is that they are construed to be non-empirical and non-scientific (Hosmer 1985, 21). As the accounting curriculum is orientated towards technical instrumentalism, the outcome is students who are equipped to make business decisions. It is argued that business decisions are taken based on objective data and therefore the subjectivity of ethical decisions warrants their exclusion from the accounting curriculum (Hosmer 1985, 21). However, this positivist position has been countered by McDonald and Donleavy (1995, 843) who argue that ethical decision-making is "a perfect exposition of normative philosophy" and therefore business ethics represents an area of applied ethics. Furthermore, social realism perceives the objectivity of knowledge to derive from its social character and not its intrinsic nature (Moore and Young 2001, 450). Therefore, the argument for the exclusion of business ethics in the accounting curriculum based on its lack of empiricism is not sound because it ignores the social codes which confer objectivity to knowledge.

Another argument is premised on the concept of "Pareto Optimality" in economics, which means that the business entity exists to optimise its profit and purely this objective should drive all the decision-making processes (Hosmer 1985, 20).The recent Steinhoff scandal, where investors lost about R300bn, shows the extent to which business value can be destroyed when business ethics are ignored. Even Milton Friedman, a long-time advocate of profit maximisation, recognised the Pareto optimality principle when he stated: "Employees should serve [the] profit maximisation motive while respecting law and basic rules of society" (Friedman 1970, 13). It appears that any enterprise that wants to achieve sustainable financial success cannot afford to treat managerial and moral competencies as mutually exclusive, but must recognise that they are interwoven factors that undergird long term business success. Therefore, a call by Powers and Vogel (1980, 44) for the business curricula to integrate managerial and moral aspects is still right on the mark.

It is also argued that ethical values are determined early in life and any form of ethics-related intervention is unlikely to affect moral change in a person (Mcdonald and Donleavy 1995, 844). This argument has been opposed on two grounds: Firstly, the goal of ethics education should be to provide a variety of approaches to ethical reasoning, which would allow students to make moral decisions on their own without the aid of the teacher (Rosen and Caplan 1980, 21). Ethics education is therefore not meant to indoctrinate students, but rather to provide them with tools of moral reasoning. Secondly, as Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg observe, a person's value system is not static, but modifiable (Mcdonald and Donleavy 1995, 844). Therefore, it can be expected that once students are capacitated with viable approaches to ethical reasoning, their moral behaviour can be influenced.

The preceding discussion shows that arguments against ethics education have been robustly countered by ethics education proponents. Based on the substance of the arguments in support of ethics education above, and the reputational crisis currently faced by the accounting profession globally and locally, it can be comfortably concluded that there is a place for business ethics education. Some research studies have shown the positive effects of such ethics interventions at institutions of higher learning and these will now be expounded on.

Research on the usefulness of business ethics curriculum

A study by Koumbiadis and Pandit (2014) found that graduates who participated in ethics courses scored higher in ethical perceptions than those that did not. Ethics education was also found to contribute positively to the moral development of students (Flynn and Buchan 2016, 122-123). These findings further challenge the argument that moral values are irreversibly set early in life. The ability of ethics education to improve the moral development of students is linked to improved ethical sensitivity of students when faced with moral dilemmas (Taylor 2013; Shawver and Miller 2017).

It is important to note that ethical sensitivity is not synonymous with ethical judgement. It means that a person appreciates the moral intensity of the ethical situation. The next question is whether such ethical sensitivity can lead to good ethical judgment. Herron and Gilbertson (2004) have found that a positive correlation exists between moral reasoning and ethical judgement. The implication of this finding is that ethics education contributes to ethical sensitivity which may translate into good ethical judgement. Therefore, SAICA's inclusion of ethics education in the accounting curriculum appears to be rational and appropriate.

It is evident from the academic literature that it is how an ethics course is structured that affects its contribution to the student's ethical sensitivity or ethical judgements. Business ethics education can be offered as a separate course or as integral to other courses (SAICA 2014, 161). There have in fact been many calls for ethics courses to be offered in an integrated format (Sadler and Barac 2005; Tweedie et al. 2013). A research study by Martinov-Bennie and Mladenovic (2015) found that an integrated ethics course increases the ethical sensitivity of students while an ethics course based on the ethics framework increases the effectiveness of their ethical judgement. Therefore, it is not sufficient to merely require an ethics component to an education programme because its outcome may be affected by how the course is structured.

Most research studies have been carried out with students as respondents. However, similar studies have been undertaken with Certified Public Accountants (CPAs) (the United States' (US) version of CAs), as research subjects. Eynon, Hill and Stevens (1997) found that completion of an ethics course in college (undergraduate university level) was found to have a positive impact on the moral reasoning abilities of CPAs. This finding was corroborated in a study by Ward, Ward and Deck (1993, 609) which found that CPAs who had completed an ethics course in college could easily distinguish between ethical and unethical behaviour. In both studies (Eynon et al. 1997; Ward et al. 1993), CPAs supported the inclusion of business ethics education in college curriculums.

While positive effects have been realized from the inclusion of business ethics education at institutions of higher learning, as shown above, such interventions have not been without criticism and challenges. Most of the Heads of Departments (HODs) of Accounting Departments at SAICA-accredited SA universities believe business ethics are best learned in industry (Barac and Du Plessis 2014, 72). One ground for HODs' preference that ethics education be left to the industry was the variety of presentation methods available for ethics courses. Rossouw (2007) echoed their frustration, finding that there were discrepancies between SAICA's objectives and the outcomes for ethics syllabuses. There are also studies which have found that ethics education does not increase the incidence of ethical reasoning, nor does it prove helpful in resolving personal ethical dilemmas (Ponemon 1993; Jones and Hiltebeitel 1995; Padia and Maroun 2012).

On the adequacy of ethics education coverage, an early study found that between one and three hours were spent on ethics in the surveyed accounting faculties (Loeb and Bedingfield 1972, 812). Another study, which had accounting professors in the accounting faculties as respondents, found that three to four hours were allocated to cover ethics (McNair and Milam 1993, 804). The limited time given to ethics education was, inter alia, blamed on a lack of time and appropriate materials (McNair and Milam 1993, 804) as well as lack of reward systems (academic and financial) to justify extending ethics education curricula (Cohen and Pant 1989; McNair and Milam 1993).

Despite the shortcomings encountered in trying to make business ethics education a part of the accounting curriculum, there is general acceptance that it is needed at institutions of higher learning (Satava, Caldwell and Richards 2006; Jackling et al. 2007; Eynon et al. 1997). The many research studies conducted on business ethics education in the accounting curriculum have been focused on whether they have impact on students' and accounting practitioners' ethical sensitivity and abilities to effect ethical judgment. Where views have been solicited on the adequacy of ethics education coverage, academics were respondents. This study therefore addresses a gap in the literature by obtaining feedback from the graduates who are still in training to become CAs. Given that they are fresh from school and have just entered the industry, their relative innocence/naivety can be helpful when providing their perceptions regarding the adequacy of the ethics education they have received at institutions of higher learning. They can also provide valuable feedback on whether business ethics education has improved their ethical awareness and enhanced their professional judgment skills. This feedback is fundamental to helping higher learning institutions assess their business ethics education efforts and to effect improvements where necessary.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODOLOGY

This study adopts a constructivism research orientation. Constructivism construes reality to be a construct of individuals' interactions with the social world (Merriam 1998, 6). The respondents in this research project underwent ethics education at SAICA-accredited universities and had formed their own views about its worth. It is their opinions on ethics education this research has solicited, and there was no positivist intention to establish a set of facts. The ultimate pursuit of investigations of this nature is to derive meaning through the interpretation of the views of others through the lens of the researcher's own views (Merriam 1998, as citied in Yazan 2015, 137). The population comprised CA trainees in SA who were at least in their second year of their post graduate training contracts. A purposive sample of 150 CA trainees was selected for this study. This sample was selected from those who had completed a SAICA-accredited BCom Accounting degree and were at least in their second year of articles/on-the-job training. Surveymonkey (www.surveymonkey.com) was used to design, collect and administer the survey online. The online survey allowed this research study to reach respondents across the entire country and mitigated against geographical (and postal delivery) limitations. Furthermore, the targeted respondents were sophisticated and had almost perpetual access to computer and internet facilities. Thus, the convenience offered by the internet-based survey led to a better-than-average response rate. Thereafter the data was subjected to statistical analysis.

Data analysis was carried out by an independent statistician. The data was analysed using four theoretical constructs, namely: a) Adequacy of coverage of ethics education, b) Importance of ethics, c) Impact of ethics education on ethical awareness and, d) Effectiveness of ethics education. Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests of normality were applied to the theoretical constructs to determine if the data was normally distributed. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine if there were significant differences when opinions were categorized according to gender, study mode (part-time or full-time) and highest academic qualification. The results were analysed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS).

RESULTS AND DATA INTERPRETATION

Of the 150 online questionnaires sent to the research subjects, 101 CA trainees responded. A response rate of 67 per cent was thus achieved, and this was considered acceptable for further statistical analysis. Table 1 presents the respondents' answers by category.

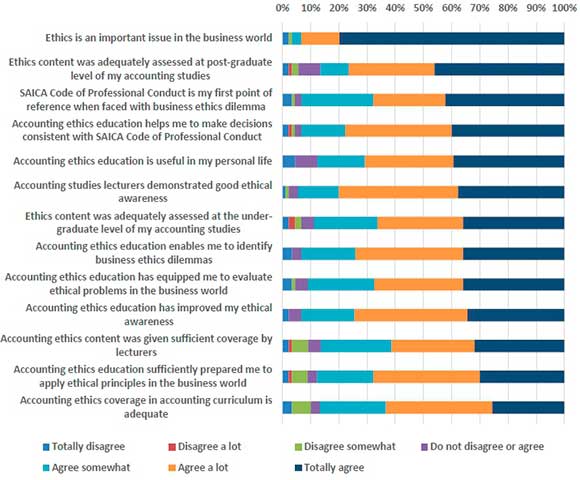

As evident in Table 1, the respondents demonstrate a stronger tendency to agree with the statements than to disagree with them. Most respondents selected "agree" to "totally agree" in the Likert scale for each question. This may represent similarity of experiences among respondents on business ethics education at SAICA-accredited institutions of higher learning.

Table 2 show variables treated as scalar measurements.

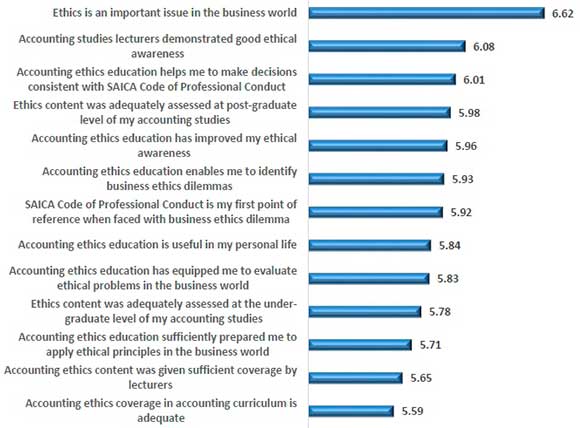

As can be seen from the graph, on average, the respondents tended to agree strongly that ethics is an important issue in the business world. "Accounting studies lecturers demonstrated good ethical awareness" and "Accounting ethics education helps me to make decisions consistent with SAICA Code of Professional Conduct" were also statements that the respondents tended to agree with, on average.

Reliability

The survey questions were presented to the respondents who were requested to rate their responses on a scale of 1 to 7; these responses were grouped based on theoretical grounds to form the latent constructs listed in Table 7. Table 7 also rates their internal consistency (reliability: Cronbach's alpha).

The theoretical constructs are as follows:

1. Adequacy of ethics education coverage (Q5.3, Q5.5, Q5.6, Q5.8, Q5.12)

2. Importance of ethics (Q5.1, Q5.4)

3. Ethical awareness: impact of ethics education (Q5.2, Q5.10)

4. Effectiveness of ethics education (Q5.7, Q5.9, Q5.11, Q5.13)

Apart from the "Importance of ethics" construct, the internal consistency is good.

Descriptive statistics

Research question 1

Do CA trainees perceive ethics education at institutions of higher learning to be adequately covered?

Table 6 shows that on the question of the adequacy of coverage of ethics education, CA trainees agree that ethics does receive sufficient attention in the accounting curriculum (mean of 5.8189 and standard deviation of 1.04990). This shows that SAICA-accredited universities are perceived to be compliant with the SAICA curriculum which expects more time to be devoted to ethics education (SAICA 2014, 161-163).

What is most interesting (and gratifying) is the highest mean of 6.08 (standard deviation of 1.019) as shown in Table 9, showing strong agreement among CA trainees that lecturers demonstrated good ethical awareness. This means the conduct of the lecturers at SAICA-accredited universities was congruent with the content of the ethics courses they presented to students. Armstrong, Ketz and Owsen (2003) expressed concern that ethics researchers have ignored the ethical principle of virtue which focuses on the individual's character (the course presenters and lecturers in this instance). Perhaps, students' observation of their lecturers' conduct is a more powerful source of ethics education than the mere content of the ethics lectures themselves. A curriculum, in that it is often reduced to written form, appears thereby to narrow the definition of its content substantially. The definition of curriculum, if expanded to be what is taught and learned may be more apt (Kelly 2004, as cited Luke et al. 2013, 7). What is learned may come from many sources over and above the formal written content of a curriculum component.

When it comes to the assessment of ethics education, CA trainees agreed that it is adequately assessed at both the undergraduate (mean of 5.78 and standard deviation of 1.363) and postgraduate (mean of 5.98 and standard deviation of 1.357) levels, as shown in Table 9. The SAICA competency framework requires SAICA-accredited universities to assess ethics content at the advanced level (level 3) which requires knowledge and rigorous demonstration of comprehension of professional ethics (SAICA 2014, 87). SAICA-accredited universities are thus perceived to be fulfilling SAICA's expectations/intentions as CA trainees agree that the assessment is adequate. What is also positive is that the degree of agreement increases in their responses to questions of the adequacy of assessment in postgraduate accounting studies. This shows the emphasis on assessment of ethics education is not exclusive to undergraduate programs, but apparently gains momentum as students move into their postgraduate studies. There were no significant differences in the opinions of CA trainees when responses were classified according to gender, mode of study and highest qualification.

Research question 2

Do CA trainees believe ethics education at universities improved their ethical sensitivity?

A strong agreement prevails among CA trainees that ethics education improved their ethical awareness, as shown in Table 11 (mean of 5.9382 and standard deviation of 1.07084). Table 12 shows that an ethical sensitivity improvement was strongly perceived to occur, both in the general sense (mean of 5.96 and standard deviation of 1.131) and in the business context (mean of 5.93 and standard deviation of 1.241). This finding dispels the notion that ethics are determined (and fixed) early in life and that any ethics intervention is futile. This finding is supported by research results of other studies which have also found a positive correlation between ethics education and improved ethical sensitivity (Koumbiadis and Pandit 2014; Flynn and Buchan 2016). Table 13 shows that no significant differences existed between the respondents' opinions when classified by gender, study mode and highest qualification.

Research question 3

Do CA trainees in SA believe that business ethics education at SAICA-accredited universities has improved their ethical judgment?

Table 12 shows that CA trainees consider ethics education to be effective (mean of 5.85 and standard deviation of 1.19038). They agree that when they are faced with ethical dilemmas, they reference their ethics education to evaluate the ethical dimensions of the situation (mean of 5.83 and standard deviation of 1.308 in Table 15) and apply it in the business world (mean of 5.71 and standard deviation of 1.343 in Table 12). This finding agrees with the outcome of the study by Eynon et al. (1993) that found that CPAs who had taken ethics courses showed comparatively good moral reasoning. Martinov-Bennie Mladenovic (2015) found that ethics education based on the ethical framework increased the effectiveness of ethical judgement. In SA, ethics are predominantly taught in the auditing course, which uses an ethical framework prescribed as by SAICA, and that could explain why this study has reached a similar finding.

There is a very strong agreement among CA trainees that ethics education in the accounting curriculum helps them make decisions that align with the SAICA Code of Professional Conduct (mean of 6.01 and standard deviation of 1.222 in Table 12). This may be testament to the appropriateness of the SAICA's competency framework which requires 12 weeks to be devoted to ethics education (SAICA 2014, 87). In response to Research Question 1, CA trainees agreed that the content of their ethics courses was adequately presented and assessed. While this meant that universities were perceived to be compliant with the SAICA's requirements on ethics coverage, it also shows that this relatively extensive coverage succeeded in implanting ethical knowledge in the students. Equipped with this knowledge, CA trainees recognised that they were then able to apply it in business.

A very interesting finding is that CA trainees agreed that ethics education in the accounting curriculum was also useful in their personal lives (mean of 5.84 and standard deviation of 1.413 in Table 12). Research studies on ethics have almost all focused on the usefulness of ethics education within the business environment. This finding regarding the influence of ethics training on their personal lives may be linked to the fact that these respondents also agreed that their lecturers had demonstrated good ethical conduct (mean of 6.08 and standard deviation of 1.019 in Table 9): in other words, the lecturers had demonstrated the good ethical conduct they were teaching, and this positive behaviour probably impacted them. While the SAICA competency framework aims to equip CA trainees with the knowledge, skills and attributes they need before entering the profession, a concomitant benefit may be that the professional skill they have learned is discovered to apply equally to life in general.

However, recent corporate scandals involving VBS and Steinhoff as well as allegations of state capture have implicated CAs. This appears to contradict the finding above as some of these CAs were possibly exposed business ethics education as espoused in the SAICA competency framework. It is possible that CA trainees are not exposed to the complex ethical dilemmas that go beyond proper and responsible execution of the audit programs or assigned tasks. Employees at a higher level (e.g. Audit managers, audit partners, financial directors, etc) may very often face difficult ethical situations as is apparent in the testimonies offered at the state capture commission. Consequently, these positive responses from CA trainees cannot be construed to apply at the higher levels of seniority. How they respond to ethical dilemmas when they reach managerial level may be informed by factors such as "the tone at top" and ethics training provided within the firm. Furthermore, it appears SAICA recognises the narrow focus of business ethics educations based on CPC. In its proposed 2025 competency framework it suggests a shift from focus on CPC compliance to making morally correct decisions in a broader context (SAICA 2019, 2). If this proposal finds expression within the accounting curricula, this may lead to ethical conduct in a broader context.

No significant differences were found when respondents' perceptions were categorized according to gender, undergraduate study mode and highest qualification. The only significant difference in opinions was found in postgraduate study mode classification (whether full-time or part-time). The Kruskal-Wallis H test found a significant mean difference between the fulltime and part-time groups regarding effectiveness of ethics education (z = -2.123, p<.05 in Table 12). Part-time students (MR = 47.31, n = 18) rated the effectiveness of ethics education significantly higher than full-time students (MR = 34.35, n = 56). A possible explanation may be that some part-time students pursue their postgraduate qualifications while already working in the industry. Consequently, they might have had more exposure to ethics-challenging situations in their work settings than those who opted to continue their postgraduate qualification studies on a full-time basis.

It should be noted that the study was carried out during the period when allegations of state capture and auditors' involvement were receiving significant media attention. It is possible that this might have influenced their strong perceptions about the importance of ethics. There is also a possibility that accounting firms were giving more attention to ethics in their in-house training to ensure they did not face the reputational crisis KPMG experienced.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

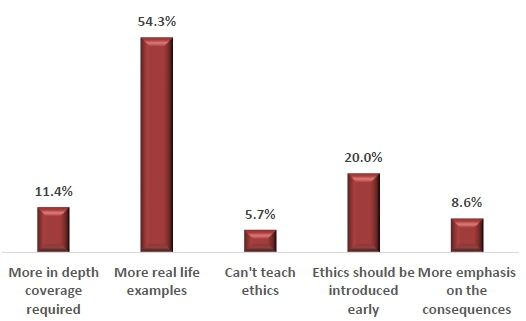

The survey concluded with a request to respondents to provide any recommendations regarding changes they would like to see in business ethics education in the accounting curriculum. The recommendations were categorised into the following general themes:

a) More in-depth coverage required

b) More real-life examples should be given

c) "Can't teach ethics" belief

d) Ethics should be introduced early in the curriculum

e) More emphasis needed on the consequences of lapses in ethics

The frequency of these types of recommendations is summarised in Table 13 below.

Of the 101 respondents, 43 participants provided recommendations. Of the 43 responses, only 35 recommendations could be categorized into the themes shown in Table 13.

Recommendation 1: More real-life examples are required

Of the 35 recommendations given, 54.3 per cent expressed concern that presently, ethics education predominantly involves memorization of the SAICA's Code of Professional Conduct. Practical applications involve case studies. However, those used lacked relevance to current realities. This is contrary to the SAICA's expectation that business ethics material should comprise real-life case material (SAICA 2014, 161) While the results of Research Question 1 showed that business ethics education is adequately covered, CA trainees are concerned about its quality and depth. SA is presently inundated with practical case study material on financial fraud and audit failures, and it is thus surprising that CA trainees strongly identified that their training was so lacking in relevant practical examples within the SA context. Thus, if students are exposed to more contemporary real-life case studies within the SA environment, they might be better prepared to respond appropriately when called on to do so in the work environment. At the time of writing this academic article, SAICA has issued a proposal for a new competency framework that, among other things, suggests a departure from CPC-focused ethics education to moral conduct in a broader sense. The 11.4 per cent of respondents who suggested the need for more in-depth coverage included suggestions with similarities to the requests for more real-life examples, and will therefore not be discussed separately.

Recommendation 2: Ethics should be introduced early

CA trainees recommended that business ethics education should be introduced from the first year of their undergraduate studies (20% of the recommendations as shown in Table 17). This suggestion is not surprising as there was a very strong agreement among CA trainees that ethics are an important issue in the business world (mean of 6.62 and standard deviation of 1.061 in Table 6). It also was apparent in the recommendations that this suggestion is driven by what is presently happening in and to the accounting profession. As was shown in the literature review, there is a dearth of resources and research opportunities in the field of professional ethics, and this has been cited for diminishing the importance of ethics education (Cohen and Pant 1989; McNair and Milan 1993; Dellaportas et al. 2014). The reputational damage already done to and the consequent crisis faced by the accounting profession in SA may thus warrant serious consideration of CA trainees' suggestion that ethics education be introduced into the curriculum from the start of their undergraduate studies.

Recommendation 3: There should be more emphasis on the ramifications of ethical violations

One of the suggestions (from 8.6% of those making recommendations) was that the consequences of unethical conduct should enjoy greater emphasis in the syllabus. One of the grave concerns in SA is that there have been virtually no legal consequences for those identified as corrupt. At the time of writing this research report, not a single accounting professional has been convicted and sent to jail due to their involvement in so-called state capture frauds. The frustration, expressed annually by the Auditor-General of SA (AGSA), is that there continues to be a total lack of consequence for "bad" management. The risk of being caught has been found to motivate students to behave more ethically (Sadler and Barac 2005, 124). If people are motivated to be more ethical for fear of being caught, the likelihood of improved ethical behaviour increases if consequences are effectively and efficiently meted out. Perhaps it is against this background that the President Cyril Ramaphosa has signed into law amendments to Public Audit Act which would empower the AGSA to issue directive for recovery of money lost due to irregularities. Therefore, one of the ways the accounting professional bodies in SA can promote good ethical conduct among their members is by ensuring that their membership rules contain serious consequences for unethical behaviour, and that these rules are effectively and efficiently implemented. This will provide current (and intimidatory) material for lecturers to convey to their students.

Suggestions for future research

The suggestion was strongly presented by CA trainees that there is a lack of current, practical case studies that shed light on audit failures within the SA context. Soliciting the opinions of lecturers at the SAICA-accredited universities may therefore provide some useful insights into how this concern has arisen and how it may be addressed.

Armstrong et al. (2003) expressed concern that the ethical principle of virtue has been ignored in research studies on business ethics. The research focus has been on rules and actions, and their consequences. Research studies exploring the impact of ethics courses that include the ethical principle of virtue will thus enrich the academic body of work on ethics education.

REFERENCES

Ansbacher, T. 1998. John Dewey's experience and education: Lessons for museums. Curator: The Museum Journal 41(1): 36-50. [ Links ]

Apple, M. W. 2004. Ideology and curriculum. Routledge. [ Links ]

Armstrong, M. B., J. E. Ketz and D. Owsen. 2003. Ethics education in accounting: Moving toward ethical motivation and ethical behavior. Journal of Accounting Education 21(1): 1-16. [ Links ]

Barac, K. and L. du Plessis. 2014. Teaching pervasive skills to South African accounting students. Southern African Business Review 18(1): 53-79. [ Links ]

Bernardi, R. A. 2004. Suggestions for providing legitimacy to ethics research. Issues in Accounting Education 19(1): 145-147. [ Links ]

Cairns, P. 2017. Steinhoff has cost investors almost R 300 billion.Moneyweb. https://www.moneyweb.co.za/investing/steinhoff-has-cost-investors-almost-r300-billion/ (Accessed 12 January 2017). [ Links ]

Cohen Commission. 1978. The Commission on Auditors' Responsibilities: Report, Conclusions and Recommendations. New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. [ Links ]

Cohen, J. R. and L. W. Pant. 1989. Accounting educators' perceptions of ethics in the curriculum. Issues in Accounting Education 4(1): 70-81. [ Links ]

Darling-Hammond, L. 1998. Policy and change: Getting beyond bureaucracy. International handbook of educational change, 642-667. Springer Netherlands. Chicago. [ Links ]

Dearden, R. F. 1981. Controversial issues and the curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies 13(1): 3744. [ Links ]

Dellaportas, S., S. Kanapathippillai, A. Khan and P. Leung. 2014. Ethics education in the Australian accounting curriculum: A longitudinal study examining barriers and enablers. Accounting Education 23(4): 362-382. [ Links ]

Eynon, G., N. T. Hills and K. T. Stevens. 1997. Factors that influence the moral reasoning abilities of accountants: Implications for universities and the profession. Journal of Business Ethics 16(12-13): 1297-1309. [ Links ]

Flynn, L. and H. Buchan. 2016. Changes in student moral reasoning levels from exposure to ethics interventions in a business school curriculum. Journal of Business and Accounting 9(1): 116. [ Links ]

Friedman, M. 1970. A Friedman doctrine: The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine 13(1970): 32-33. [ Links ]

Haas, A. 2005. Now is the time for ethics in education. The CPA Journal 75(6): 66. [ Links ]

Hoffman, W. M. and J. M. Moore. 1982. Results of a business ethics curriculum survey conducted by the Center for Business Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 1(2): 81-83. [ Links ]

Herron, T. L. and D. L. Gilbertson. 2004. Ethical principles vs. ethical rules: The moderating effect of moral development on audit independence judgments. Business Ethics Quarterly 14(3): 499-523. [ Links ]

Hosmer, L. T. 1985. The other 338: Why a majority of our schools of business administration do not offer a course in business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 4(1): 17-22. [ Links ]

IAASB see International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

IASB see International Accounting Standards Board.

International Accounting Standards Board. 2016. International Accounting Standard 1: Presentation of Financial Statements. SAICA Handbook 2016-2017, Volume 1. [ Links ]

International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. 2017. ISA 200: Overall objectives of the independent auditor and the conduct of an audit in accordance with the International Standards on Auditing. Handbook of International Quality Control, Auditing, Review, Other Assurance and Related Services Pronouncements, 2016-2017 Edition, Volume 1. [ Links ]

Jackling, B., B. J. Cooper, P. Leung and S. Dellaportas. 2007. Professional accounting bodies' perceptions of ethical issues, causes of ethical failure and ethics education. Managerial Auditing Journal 22(9): 928-944. [ Links ]

Joffe, H. 2017. KPMG on the ropes. Financial Mail. https://www.businesslive.co.za/fm/features/2017-10-05-kpmg-on-the-ropes/ (Accessed 12 January 2017). [ Links ]

Jones, S. K. and K. M. Hiltebeitel. 1995. Organizational influence in a model of the moral decision process of accountants. Journal of Business Ethics 14(6): 417-431. [ Links ]

Kohlberg, L. and R. Mayer. 1972. Development as the aim of education. Harvard Educational Review 42(4): 449-496. [ Links ]

Koumbiadis, N. and G. Pandit. 2014. Has the AICPA changed the accounting profession for better or worse? The case of educational change. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change 10(2): 190-215. [ Links ]

Laing, R. 2017. Banks suffer R 86bn wipeout in the wake of Pravin Gordan's dismissal. Financial Mail. https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/markets/2017-03-31-banks-lose-r86bn-of-their-market-cap-in-wake-of-pravin-gordhans-dismissal/ (Accessed 12 January 2017). [ Links ]

Loeb, S. E. and J. P. Bedingfield. 1972. Teaching accounting ethics. The Accounting Review 47(4): 811-813. [ Links ]

Luke, A., A. Woods and K. Weir. 2013. Curriculum design, equity and the technical form of the curriculum. Curriculum, syllabus design and equity: A primer and model, 6-39. [ Links ]

Martinov-Bennie, N. and R. Mladenovic. 2015. Investigation of the impact of an ethical framework and an integrated ethics education on accounting students' ethical sensitivity and judgment. Journal of Business Ethics 127(1): 189-203. [ Links ]

McDonald, G. M. and G. D. Donleavy. 1995. Objections to the teaching of business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 14(10): 839-853. [ Links ]

McNair, F. and E. E. Milam. 1993. Ethics in accounting education: What is really being done. Journal of Business Ethics 12(10): 797-809. [ Links ]

Merriam, S. B. 1998. Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Revised and expanded from "Case study research in education.". Jossey-Bass Publishers, 350 Sansome St, San Francisco, CA 94104. [ Links ]

Moore, R. 2000. For knowledge: Tradition, progressivism and progress in education - reconstructing the curriculum debate. Cambridge Journal of Education 30(1): 17-36. [ Links ]

Moore, R. and M. Young. 2001. Knowledge and the curriculum in the sociology of education: Towards a reconceptualisation. British Journal of Sociology of Education 22(4): 445-461. [ Links ]

Ornstein, A. C. 1990. Philosophy as a basis for curriculum decisions. The High School Journal 74(2): 102-109. [ Links ]

Padia, N. and W. Maroun. 2012. Ethics in business: The implications for the training of professional accountants in a South African setting. African Journal of Business Management 6(32): 9274- 9278. [ Links ]

Palys, T. 2008. Purposive sampling. The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods 2(1): 697- 698. [ Links ]

Pinar, W. F. 2007. Crisis, reconceptualization, internationalization: US curriculum theory since 1950. East China Normal University, Shanghai. [ Links ]

Ponemon, L. A. 1993. Can ethics be taught in accounting? Journal of Accounting Education 11(2): 185- 209. [ Links ]

Powers, C. W. and D. Vogel. 1980. Ethics in the education of business managers. Hasting-on-Hudson; NY: Institute of Society. Ethics and the Life Sciences. [ Links ]

Rosen, B. and A. L. Caplan. 1980. Ethics in the undergraduate curriculum. The teaching of Ethics IX. The Hastings Center, Institute of Society, Ethics and the Life Sciences, Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. [ Links ]

Rossouw, G. J. 2007. The SAICA syllabus for ethics: Does it all add up? South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 10(3): 384-393. [ Links ]

Sadler, E. and K. Barac. 2005. A study of the ethical views of final year South African accounting students, using vignettes as examples. Meditari Accountancy Research 13(2): 107-128. [ Links ]

SAICA see The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants.

Satava, D., C. Caldwell and L. Richards. 2006. Ethics and the auditing culture: Rethinking the foundation of accounting and auditing. Journal of Business Ethics 64(3): 271-284. [ Links ]

Shawver, T. J. and W. F. Miller. 2017. Moral intensity revisited: Measuring the benefit of accounting ethics interventions. Journal of Business Ethics 141(3): 587-603. [ Links ]

The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants. 2014. The Competency Framework: Detailed guidance for the academic programme. [ Links ]

The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants. 2019. The proposed SAICA competency framework. http://sdg.saica.co.za/Portals/5/CPD%20Framework.pdf?ver=2019-05-02-110805-690 (Accessed 27 July 2019). [ Links ]

Taylor, A. 2013. Ethics training for accountants: Does it add up? Meditari Accountancy Research 21(2): 161-177. [ Links ]

Tweedie, D., M. C. Dyball, J. Hazelton and S. Wright. 2013. Teaching global ethical standards: A case and strategy for broadening the accounting ethics curriculum. Journal of Business Ethics 115(1): 1-15. [ Links ]

Ward, S. P., D. R. Ward and A. B. Deck. 1993. Certified public accountants: Ethical perception skills and attitudes on ethics education. Journal of Business Ethics 12(8): 601-610. [ Links ]

Yazan, B. 2015. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. The Qualitative Report 20(2): 134-152. [ Links ]

Young, M. 2007. Bringing knowledge back in: From social constructivism to social realism in the sociology of education. Routledge. [ Links ]