Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.34 n.3 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.20853/34-3-3495

GENERAL ARTICLES

Photovoice as a critical reflection methodology for a service learning module

M. JordaanI; V. PieterseII

IDepartment of Informatics, University of Pretoria, South Africa, e-mail: martina@up.ac.za / https://orchid.org/0000-0003-0110-6600

IIDepartment of Computer Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa, e-mail: vreda.pieterse@tuks.co.za / https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7487-2704

ABSTRACT

The article examines the value of using photovoice to assist reflection in a service learning module. Students were required to complete a reflective assignment in order to facilitate critical reflection on experiences during their community-based projects. They had to identify a specific incident during the execution of their project which they experienced as a challenge. They had to take a photograph to depict the challenge and at the end of their project, complete a reflective questionnaire about the identified challenge. The concepts of photovoice as a methodology tool were used to determine the value of such a reflective assignment for students.

The study shows that identifying the challenge during the execution of their project enhanced the students' creativity during the project and assisted reflection after completing the project. Furthermore, the photographic reminder of the incident they had identified as a challenge, helped the students to recall their experiences and resulted in a more meaningful reflection.

Keywords: service learning, photovoice, reflection

INTRODUCTION

The Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, has as one of the compulsory undergraduate courses, a Community-Based Project (code: JCP). It entails that students must work at least 40 hours in the community and afterwards reflect on their experiences (Jordaan 2012, 225).

A large number of students enrol for the module every year. In 2017 a total of 1 575 students completed the module. The students undertook 464 different projects with 231 different campus-community partners. The projects varied from teaching mathematics and science to school learners, to basic renovation and building projects, repairing the computers in the computer centres of schools and non-profit organisations, and developing enrichment projects for animals in zoos and shelters (Jordaan 2014, 276). Most of the campus-community partners (46,8%) are situated in Pretoria and the broader area around Pretoria that is called the Tshwane region. However, the students also undertook projects in seven neighbouring countries, namely Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Swaziland, Malawi, Mozambique and Lesotho.

The students were required to photograph every step of the execution of their projects. They used these photographs for their final presentation. The students were requested to submit a photograph of the challenge they experienced during the execution of the project in order to emphasise reflection on the challenges they experienced. Students had to give their reason for identifying the specific photograph as a depiction of a challenge they experienced.

The article examines the impact of the use of a photographic reminder when students reflected on their challenges. The investigation applies photovoice concepts to analysing the students' reflections and to draw conclusions.

VISUAL RESEARCH

Visual research is becoming an easy technique to use as it is relatively cheap and user-friendly technology. Photographs have been used in various types of studies. Photovoice (Wang and Burris 1997), Photo Elicitation Interview (PEI) (Epstein et al. 2006), Participant Authored Audiovisual Stories (PAAS) (Ramella and Olmos 2005), and hermeneutic photography (Hagedorn 1994) have been used for many years in the health field as well as in other disciplines.

The concepts of photovoice are used in this study. These concepts provide a hands-on means of sharing viewpoints, knowledge and information. Originally photovoice promoted community support among historically marginalised groups, especially in the field of public health. However, researchers have increasingly followed a photovoice process to substitute discussions between the participants and the broader community. Photovoice has also been used as a tool for social change, particularly for youth and marginalised groups (Kelly 2017).

Photovoice entails that community members take photographs in their communities. Then the photographs are analysed and categorised in the areas which are represented (Strawn and Monama 2012, 535). This enables people to share knowledge and deliberate on important issues (Joubert 2012, 454). Photovoice has also been used in educational research (Ciolan and Manasia 2017). Various researchers have indicated the value of photographs for facilitating reflection and discussions (Mclntyre 2003; Wang and Burris 1997). Photovoice has been used as an assessment method by (Mulder and Dull 2014; Garner, 2014). Mulder and Dull (2014) used the concepts of photovoice in a social work classroom where they developed a process for students to engage in self-reflection. After that, the students went to a debriefing session as well as holding a dialogue with their peers. Students will respond on certain prompts by taking a photograph. This can reveal insight into their morals and viewpoints. Photovoice usually elicits the students' personal responses and histories, and an emotional approach is usually the commonly taken approach.

Photovoice has the possibility of the integration of greater visual stimuli and processes, and studies have shown that it fostered creativity among students. It also improved their valuation of personal expertise, reflection, and expression (Fletcher and Cambre 2009). Cook and Buck (2010) support photovoice as a method to assist students to describe and answer questions on an image. Through photovoice students could reflect on new experiences, what they enjoyed and what they would have done differently and what they learned from their experiences.

EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION

Bringle and Hatcher (1996) define service learning as a curriculum- and credit-based educational approach. Students have to participate in organised and well-structured service activities that address the specific needs of an identified community. The importance of reflection in this process is addressed in all the research literature on service learning.

The students who participate in their service learning projects gain knowledge about the domain of the project and are likely to learn a wide range of practical skills and competencies related to their project because they confront and have to solve real-world problems in order to achieve the project's goals. We base this claim on Dewey's (Dewey 1938) problem-based learning theory and Kolb's (Kolb 1984) experiential learning theory.

The real-world situations that are an integral part of the projects the students have to tackle, create opportunities for the students to develop their coping skills when problems arise. Folkman and Lazarus (1985, 150) discriminate between problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. Other researchers use the term assimilative coping for problem-focused coping, and the term accommodative coping for emotion-focused coping. This conceptual distinction between assimilative and accommodative coping suggests that assimilative coping is aimed at actively altering the environment to suit oneself and that accommodative coping is aimed at altering oneself to adjust to the environment (Brandtstãdter 1992, 142). We have observed our students applying both assimilative and accommodative coping strategies to deal with the problems they faced during their projects.

The theories of symbolic interactionism and individual-environmental interaction form the basis for using reflective photography. According to Lewin (Harrington and Schibik 2003, 27), the interchange between individuals and their environment results in the individual specific behaviour.

The meaning that individuals accredit to certain symbols is described by the theory of symbolic interactionism (Harrington and Schibik 2003, 27). According to Blumer (1986, 84), a person acts towards things linked to the meaning they have for it. The social interaction that a person has with other people give meaning to these things. The meanings are then modified through the individual's interpretation of the things that the person encounters.

EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING AND REFLECTION

Part of the experiential learning for the social justice process is putting students in situations where they may not feel comfortable. Learning occurs when students apply classroom knowledge in real-world settings and work for positive change in the community. After that, they return to the classroom to reflect critically on their service experiences. Experiential learning, particularly when guided by discussions with faculty members, staff members and peers, can help students question "assumptions, analyses, conclusions and actions". In addition, they may help to deepen the students' understanding of the material covered in courses, increase critical thinking in complex and ambiguous situations, and show students how to engage in lifelong learning (Eyler 2009, 26). Reflection encourages students to think about how the services have affected them. They reconstruct what they have learned and add their personal insights gained during their service experience (Gerholz, Liszt and Klingsieck 2017, 48).

There is also an expectation that students will gain perspective through interactions that are appropriate, sensitive, and self-critical. These experiences should also help students to appreciate the formal and informal knowledge, wisdom, and skills of the population with which they are working. Asking students to go into communities and learn through experience can be counterproductive, as simply experiencing a different situation does not automatically lead to understanding and may even confirm previous worldviews and stereotypes. Lecturers should, therefore, aid students to connect their direct observations with the abstract concepts covered in their courses, using mediated and structured reflection and discussion. The lecturer should facilitate learning, helping students to process what they see in communities. Students' increased capacity to think critically and communicate articulately about their community experience should be used as measures for evaluating their success (Cone and Harris 1996, 41).

Student's reflection on their service learning experience is one of the most important parts of the final assessment. The experience only becomes educative if critical reflective thought creates a new meaning for the experience. It is important for students to have a clear understanding of the way that the reflection assignment will be assessed (Hatcher and Bringle 1997, 153). Since reflection gives students the opportunity to promote a deeper understanding of the world, lecturers ought to facilitate critical reflection among students (Tornabene, Nowak, and Vogelsang 2012).

Students have to reflect on the impact that their service learning experiences had on them, as well as on the community. Through their service learning experience, students may acquire various life skills. This includes skills such as leadership, communication and interpersonal skills, but students also develop an understanding of social issues in the communities and become aware of personal, social and cultural values (Jordaan 2012, 231). Through the project, students may make a positive contribution to the quality of life of individuals in a community (Dukhan, Schumack and Daniels 2008). Only then can it be said that a service-learning module has achieved its objective successfully.

Various of reflection assignments are proposed by lecturers like journals, experiential research paper, ethical case studies, directed readings class presentations and discussions and electronic reflection as well as concept mapping (Van Rensburg et al. 2018, 609).

Service learning shows students that each of them can make a difference. It promotes civic education and citizenship. Even though all the students' projects are not always successful, students learn from their mistakes by engaging in a continuous sequence of action and reflection (Mendel-Reyes 1998, 38).

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The fundamental question of this research is whether it is possible to use the concepts of photovoice as a methodological tool to facilitate effective reflective learning and if this will ensure a deeper understanding of the service learning endeavour?

METHODOLOGY

The students' photographs and a questionnaire, was used to compare the perceived outcomes. The findings from the students' photographs were combined with the responses to the questionnaire.

ETHICS

Ethical approval was received from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology of the University of Pretoria. It is extremely important to consider ethics in a photovoice study. The Protection of Personal Information Act, No 4 of 2013 promotes the protection of personal information by public and private bodies. When and how you choose to share your information requires the consent of the relevant persons (RSA 2013). Students knew about the ethical importance of the photographs they took. They had to submit written permission from the campus-community partner to take any photographs for their assignments. Each student also gave written permission to the lecturer for using their photographs in the public domain. The photographs in the article serve as examples and do not identify campus-community members or students.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The purpose of our photovoice proj ect was to create an opportunity for the participating students to reflect on their challenges and how they overcame these challenges. Photovoice was the means for the researchers to understand what the students who had enrolled in the Community-based Project (Code: JCP) saw as a challenge while they executed their projects. As part of their assignments, students had to take at least five photographs while executing their project. One of these photographs had to indicate the challenge that each student encountered. It required students to think critically about how they executed their projects, what problems they encountered during the project and how they solved these problems.

Each student submitted the photograph to the lecturer before or during the final presentation session. It was not compulsory to submit such a photograph and students did not forfeit marks if they did not identify a challenge in a photograph. The photographs were uploaded to the E-learning management system for the other students to view. The team leader had to complete a questionnaire on the photograph they uploaded. The researchers used Qualtrics1 to analyse the responses. Each photograph with the combined feedback from the questionnaire was treated as a unit. When linked to the student's written feedback, the photograph has relevance, and the visual perspective strengthened the narrative.

ANALYSIS

Although photovoice adds a richness to research, some limitations must be considered when using it. Julien, Given and Opryshko (2013, 260) state that participants might take pictures that are beyond the scope of the research and this would affect the dissemination of the research findings.

All the data were qualitatively coded and categorised for themes using the stepped approach of evaluating photovoice data (Oliffe et al. 2008, 532). The approach consisted of three stages, namely appraisal, the identification of themes and interpretation. During the appraisal phase, we examined the conformity between the written (the students' feedback on the questionnaire) and the visual data. After that, we identified themes in the collection after removing any that did not conform. Of this data, 16 questionnaires were not used because the photographs taken did not reflect the challenge. For example, one group stated "... we painted the JCP emblem on 3 bins" and another group submitted a photograph with the code of the module as a challenge (see Photograph 1). Finally, we interpreted the photographs, where we closely examined each photograph, probing the context and meanings of individual images.

The first step was to obtain the perspective of the student who photographed the image. This was done by evaluating the narrative feedback along with the photograph. The goal was to understand the group's intent when taking a photograph and the group's relation to the challenge they identified.

The second step was for the researchers to study the images from their perspective. The goal was to examine the details of the photographs. Thereby supporting or contest the groups' feedback in the questionnaire about the photograph. The third step was to cross-analyse the photos to find repeated themes in the photographs as well as the narratives.

The last step was to link the themes to theories. In this study, photovoice images were examined from each student's perspective and then from the researchers' s perspective. The data were qualitatively analysed separately from the primary photovoice data but were added to the final step of identifying the analytic theme and patterns.

RESULTS

Not all of the students found an aspect of their projects to be challenging, and some found it difficult to photograph their challenge. These challenges included group dynamics, time management or disagreement with their campus-community partner. In 2017 478 groups completed the module of which 203 (42,47%) submitted and answered the questionnaire. The 203 responses given on the questionnaires were correlated with the photographs submitted. Of these, 16 questionnaires were not used as the photographs taken did not reflect the challenge.

In some cases, the students did not complete the questionnaire or submit a photograph but stated that their challenge was an emotional one, such as disagreement between the students and the community or the team members among themselves. Such challenges are difficult to visualise or photograph.

Most of the students identified their challenges in the middle (48%) of executing their project. Other students stated that they had identified the challenge at the beginning (29%) and at the end of the project (23%). Most (92,6%) of the groups stated that the challenge had been solved. Those who could not solve the problem said that they had worked around the problem or found an alternative solution to the challenge. The majority of the students (75,5%) stated that the challenge was that of the team, whereas 11,9% of the students said that the challenge was that of the community and the team.

Through the research, four major themes emerged from the data, namely a cognitive theme, a practical theme, an affective theme and a reflective theme. The first three themes focused on the activities that influenced the students' learning. Each theme is discussed, and selected photographs presented to give examples of the students' reflective photographs. Only a small sample of the photographs is presented owing to privacy restrictions, and a large number of photographs were reviewed. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the photographs by their themes. Most of the photographs (74,87%) reflected a practical theme.

Photographs indicating a cognitive theme showed how students were engaged in the project and the challenge that forced them to learn something new from their project. The students identified a particular challenge because they did not have enough knowledge or skills to complete the project. The students gave reasons why they identified something related to the project as a challenge. Although most of the photographs in this category identified students, these photographs are published because we received written consent from the students to use their photographs for publication.

"We are inexperienced when it comes to building. We had no prior knowledge of how to use the machine, and I had to fix it."

and

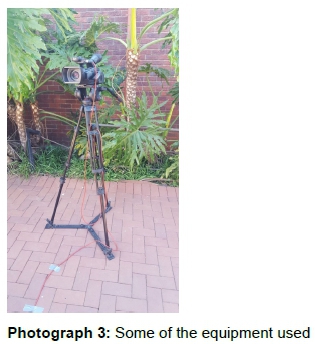

"None of us had ever operated a camera or microphone equipment in the past."

In photograph 2 the students indicated that they could not manage to fit a door, mainly because they did not have prior knowledge of how to fit it.

In photograph 3 the student took a picture of a camera. As part of their project, the students had to create a promotional video for a local museum. This was the first time that they had used this equipment, and the students had to learn how to use the video camera.

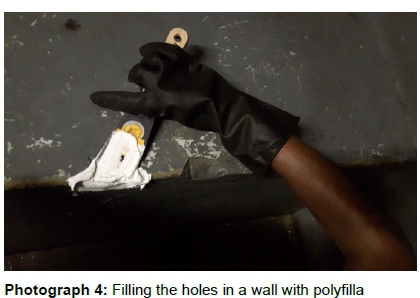

The photographs that indicated a practical theme indicated how students solved the problem they had identified. The students did not necessarily learn a new skill to solve the problem or challenge. This included poor planning on the part of the team, their awareness of their safety or that the team did not have the correct tools for the specific tasks.

"Repairing cracks/holes was not what we thought we would encounter. We only thought of painting. So as a team, we had to come up with a way to repair without using cement because cement is much expensive and requires some skills to work with it."

and

"It represents the general struggle we had with the living conditions which were not what we were used to (coming from the city). It was difficult, and the wire cut our hands."

and

"It hindered our work a lot as we spent valuable time trying to do silly tasks such as open paint cans due to the fact that we didn't plan ahead for certain details of the project."

and

"It was difficult to put in and measure the ceiling boards, but we knew how much it would mean to the ladies if we did this for them."

Photograph 4 illustrates students applying polyfilla to a hole in a wall. They had to find the right tools to do the job correctly, and the students knew what to do and how to do it.

In photograph 5 the students stated that they had encountered a problem with removing the top of the basin at a non-profit organisation. The basin had to be removed as it was loose. The wooden cabinet had rotted around the basin and was, therefore, a safety risk for the residents.

In their narrative about photograph 6, the students said they had to clean the dust from the old computers so that they would be functional again.

The students who took Photograph 7 said that they had a problem with an electrical extension and had to make sure it was safe.

The affective theme indicated that students showed some reaction or emotion linked to their challenge. The students were more aware of how privileged they were or that they were emotionally involved with the campus-community partner. A photograph showing the children of the shelter was stated to be a challenge, with the comments:

"It plays on your heartstrings."

and

"It was the most tiring job to do."

and

"It was literally back-breaking work; this was the most difficult part of the project."

and

"As the weather made it really hard to get out of bed and into the field."

and

"I could see by the level of concentration of the child that she lost focus."

Students found it emotionally exhausting to work in children's homes, baby shelters, poor schools and homes for the aged.

In photograph 8 the students were repairing benches at a pre-school. The students blanked out the children's faces for ethical reasons as the students had not received consent from the children's parents to use the photograph. They said that the learners in the school where they worked were very intrigued by what they were doing, but that made it difficult to complete the renovation project. The learners kept on questioning what they were doing, and the students found the physical work, in addition to the many questions, was exhausting.

In relation to Photograph 9, the students said that it was heartbreaking to work at a cat sanctuary because so many cats had been abused before they came to the sanctuary. The students took a picture of a happy cat as the organisation did not allow them to take pictures of the abused cats.

The reflective theme indicated the completed task. It showed the final project after the challenge had already been solved.

"The team had to properly redo a pavement which was destroyed by the growth of roots from underneath. We had to remove the root using pick-axes and a saw because a chainsaw was not available for the team to use. It took a lot of time and energy to do."

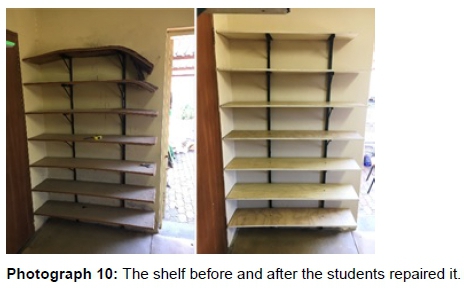

Photograph 10 showed the before-and-after photograph of one of the shelves they had to repair at one of the non-profit organisations.

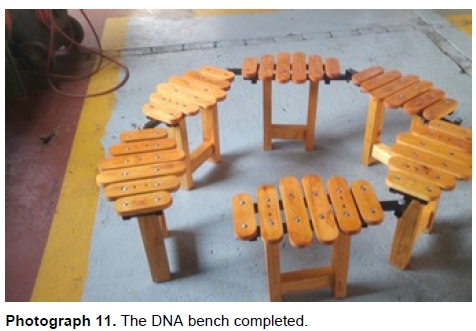

Designing and building a wooden bench for a local zoo that requested it should look like a DNA string (Photograph 11) was a huge challenge for a group of Mechanical Engineering students.

In response to the question of how they would overcome the challenge, the students either spoke about the planning of the project or the execution of the project. The students said that they would choose an alternative plan and that they should have planned better. The improved planning included that they should have made sure that they had the correct tools, or whether the challenge was unavoidable and had to be overcome to complete the project.

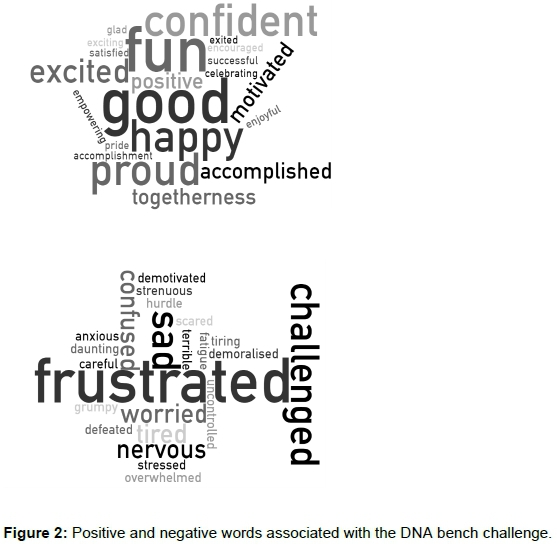

The emotions linked to the challenge showed a wide scope of feelings. After identifying the challenge, some students used words like "frustrated", "worried", "stressed", "nervous" and "feeling like giving up"; but others used words such as "emotional", "excited", "positive and up for the challenge", "motivated" and "empowering". After solving the challenge, the students expressed their feelings with the words "proud", "accomplished" and "happy that we succeeded". See the word clouds in Figure 2 for more identified words.

DISCUSSION

The participant-produced photographs have the possibility to provide alternative outcomes than what the goal of which the approach was originally designed for. Students who did not take a particular photograph of their challenge had difficulty with identifying an aspect of their project that had been a challenge for them. Some students did their final presentation two or three months after completing their project and, when questioned about this, they were unable to identify a specific challenge. Other students feared that they might lose marks if they identified a challenge. Not being able to identify a challenge might be a sign of ego-defensive repression of the specific incident as a natural subconscious accommodative coping strategy. Ego-defensive repression means the suggestion that our minds repress the thoughts at the source of our anxieties, instead of contemplating them consciously (Erdelyi and Goldberg 2014, 400). One tends to forget unpleasant experiences, especially when one has positive experiences close in time to the less pleasant experiences. Feelings such as satisfaction and pride tend to ultimately overwhelm negative feelings such as inability, shame and frustration. It could explain why our students had reported fewer challenges in the past than those who recently used photovoice. In this case, the students took photographs to depict their challenges. These photos reminded them of their hardships when they compiled their final report.

The students can internalise the challenges that they encounter in the proj ect in ways which are relevant and meaningful to them. This enables them to integrate or accommodate the experiences in their body of knowledge. The photographs and feedback on the questionnaire informed the lecturer about what the students experienced and what the students thought was a challenge in their project. The students used their smartphones or cameras, and it empowered the lecturer to gain an understanding of the project and the environment where the students did their project. The lecturer could use these captioned photographs to qualitatively assess each student's experience and learning from the project. The evaluation was used not only to assess the students but also to promote the value of community engagement.

CONCLUSION

This article was aimed at determining the use of photovoice as a reflection tool for a large-scale service learning module. It is argued that photovoice concepts are a possible additional option for a reflective assignment. Meaningful reflection opportunities have a positive effect on student's service learning experience (Chan, Ngai, and Kwan 2017; Mabry 1998). Freire (1970) emphasises that a visual image can be a powerful tool to facilitate an individual's critical thinking about the forces and factors influencing his/her life.

Students had to take a photograph of a specific challenge that they encountered during the execution of the project. Students mainly identified the challenge in the middle of their project. They indicated overall that they had to solve the problem to complete the project. It was easier for students to take photographs with a cognitive, practical or reflective theme than with an emotional theme. Students who identified a challenge and took a photograph of their challenge showed a deeper understanding of what they learned during their service learning project than students who did not submit a photograph. Many of the teams did not submit a photograph or report any of the challenges they had encountered, possibly because some of them might have repressed the memory of the challenge or found it impossible to photograph the challenge, e.g. problems with time management.

The strength of the photovoice process enabled the students and the researchers to see beyond the categories assigned to them. The flexibility of such a reflection could help the millennial generation increase their reflective learning capacities as it embraces their multimedia learning style. It gives the service-learning lecturer additional opportunities to persuade students to reflect on their service learning endeavour.

NOTE

1 https://www.qualtrics.com/uk/

REFERENCES

Blumer, H. 1986. Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Univ of California Press. [ Links ]

Brandtstadter, J. 1992. Personal control over development: Some developmental implications of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy: Thought control of action, 127-145. [ Links ]

Bringle, R. G. and J. A. Hatcher. 1996. Implementing service learning in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education 67(2): 221 -239. [ Links ]

Chan, S. C. F., G. Ngai and K. Kwan. 2017. Mandatory service learning at university: Do less-inclined students learn from it? Active Learning in Higher Education 1469787417742019. [ Links ]

Ciolan, L. and L. Manasia. 2017. Reframing photovoice to boost its potential for learning research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16(1), 1609406917702909. [ Links ]

Cone, D. and S. Harris. 1996. Service-Learning practice: Developing. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 3: 31 -43. [ Links ]

Cook, K. and G. Buck. 2010. Photovoice: A community-based socioscientific pedagogical tool. Science Scope 33(7): 35-39. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. 1938. Experience and education. The Kappa Delta Pi Lecture Series - Collier Books. New York: Collier Macmillan Publishers. [ Links ]

Dukhan, N., M. R. Schumack and J. J. Daniels. 2008. Implementation of service-learning in engineering and its impact on students' attitudes and identity. European Journal of Engineering Education 33(1): 21-31. [ Links ]

Epstein, I., B. Stevens, P. McKeever and S. Baruchel. 2006. Photo elicitation interview (PEI): Using photos to elicit children's perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5(3): 1-11. [ Links ]

Erdelyi, M. H. and B. Goldberg. 2014. Let's not sweep repression under the rug: Toward a cognitive psychology of repression. Functional Disorders of Memory, 355-402. [ Links ]

Eyler, J. 2009. The power of experiential education. Liberal Education 95(4): 24-31. [ Links ]

Fletcher, C. and C. Cambre. 2009. Digital storytelling and implicated scholarship in the classroom. Journal of Canadian Studies 43(1): 109-130. [ Links ]

Folkman, S. and R. S. Lazarus. 1985. If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48(1): 150-170. [ Links ]

Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder & Herder. [ Links ]

Garner, S. L. 2014. Photovoice as a teaching and learning strategy for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today 34(10): 1272-1274. [ Links ]

Gerholz, K. H., V. Liszt and K. B. Klingsieck,. 2017. Effects of learning design patterns in service learning courses. Active Learning in Higher Education 1469787417721420. [ Links ]

Hagedorn, M. 1994. Hermeneutic photography: An innovative esthetic technique for generating data in nursing research. Advances in Nursing Science 17(1): 44-50. [ Links ]

Harrington, C. E. and T. J. Schibik. 2003. Reflexive photography as an alternative method for the study of the freshman year experience. NASPA Journal 41(1): 23-40. [ Links ]

Hatcher, J. A. and R. G. Bringle. 1997. Reflection: Bridging the gap between service and learning. College Teaching 45(4): 153-158. [ Links ]

Jordaan, M. 2012. Sustainability of a community-based project module. Acta Academica 44(1): 224-246. [ Links ]

Jordaan, M. 2014. Community-based Project Module: A service-learning module for the Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology at the University of Pretoria. International Journal for Service Learning in Engineering, Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship (Special issue): 269-282. [ Links ]

Joubert, I. 2012. Children as photographers: Life experiences and the right to be listened to. South African Journal of Education 32(4): 449-464. [ Links ]

Julien, H., L. M. Given and A. Opryshko. 2013. Photovoice: A promising method for studies of individuals' information practices. Library & Information Science Research 35(4): 257-263. [ Links ]

Kelly, K. J. 2017. Photovoice: Capturing American Indian youths' dietary perceptions and sharing behavior-changing implications. Social Marketing Quarterly 23(1): 64-79. [ Links ]

Kolb, D. 1984. Experiental learning. Experience as source of learning and development. USA: Prentice-Hall. Inc. [ Links ]

Mabry, J. B. 1998. Pedagogical variations in service-learning and student outcomes: How time, Contact, and reflection matter. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 5: 32-47. [ Links ]

McIntyre, A. 2003. Through the eyes of women: Photovoice and participatory research as tools for reimagining place. Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 10(1): 47-66. [ Links ]

Mendel-Reyes, M. 1998. A pedagogy for citizenship: Service learning and democratic education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning 73: 31 -38. [ Links ]

Mulder, C. and A. Dull. 2014. Facilitating self-reflection: The integration of photovoice in graduate social work education. Social Work Education 33(8): 1017-1036. [ Links ]

Oliffe, J. L., J. L. Bottorff, M. Kelly and M. Halpin. 2008. Analyzing participant produced photographs from an ethnographic study of fatherhood and smoking. Research in Nursing & Health 31(5): 529-539. [ Links ]

Ramella, M. and G. Olmos. 2005. Participant authored audiovisual stories (PAAS): Giving the camera away or giving the camera a way. Papers in Social Research Methods: Qualitative Series 10: 1 - 24. [ Links ]

RSA. 2013. Protection of Personal Information Act (37067). Cape Town: Government Gazette 581. [ Links ]

Strawn, C. and G. Monama. 2012. Making Soweto stories: Photovoice meets the new literacy studies. International Journal of Lifelong Education 31(5): 535-553. [ Links ]

Tornabene, L., A. V. Nowak and L. Vogelsang. 2012. Using the FotoFeedback method to increase reflective learning in the Millennial generation. Journal of Effective Teaching 12(2): 80-90. [ Links ]

Van Rensburg, G. H., Y. Botma, T. Heyns and I. M. Coetzee. 2018. Creative strategies to support student learning through reflection. South African Journal of Higher Education 32(6): 604-618. [ Links ]

Wang, C. and M. A. Burris. 1997. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior 24(3): 369-387. [ Links ]